Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Second Nature: A Review

Uploaded by

Kim Dyan CalderonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Second Nature: A Review

Uploaded by

Kim Dyan CalderonCopyright:

Available Formats

CALDERON, KIM DYAN A.

1 October 2011

MA SDS SDS 298 Anthropology of Development (SAT 9:00-12:00)

SECOND NATURE: A Review

The lessons that the villages of Sandaya and Toly,

featured in Second Nature, teach us are far from

the conventionally accepted thesis of

environmentalism. The notion that

environmental degradation can be traced from

anthropogenic causes has come to be the most

widely acknowledged understanding of ecological

destructions since the Industrial Revolution.

Descending upon the roots of this paradigm, to

which most of todays international development

agencies and government agencies adhere to,

would lead one to the year 1968, when Garret

Hardins Tragedy of the Commons rose into

popularity. This article assumes human rationality

in dealing with what common resources are

available to him. Using the herdsman in a

pastureland scenario to illustrate the simplistic

calculus governing utility, Hardin explains that the

only rational decision for a herdsman to make is

to increase his herd, since the positive utility he

derives by doing so is greater than its negative

utility. That negative utility pertains to

overgrazing, the effects of which are shared by all

herdsmen in the pasture. Such scenario leads him

to the following conclusion:

Adding together the component partial utilities, the

rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible

course for him to pursue is to add another animal to

his herd. And another.... But this is the conclusion

reached by each and every rational herdsman

sharing a commons. Therein is the tragedy. Each

man is locked into a system that compels him to

increase his herd without limit -- in a world that is

limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men

rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society

that believes in the freedom of the commons.

Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all (Hardin

1968).

While this knowledge holds truth to it, the danger

lies in applying this truism to come up with

narrativessomething that (social) research has

been concerned about for some time. The

commonsthe pastures in this particular

scenario, has been adapted to pertain to forests,

oceans, the atmosphere, even the space; and

humans, armed with their rationality, exist and

continue to grow exponentially to exploit natural

resources in an unsustainable manner. This

narrative has guided policy in the developing

world, with proposed solutions packaged in the

form of privatization, resource taxes, and

regulation.

In Africa, development works are funded by

international institutions inclined to subscribe to

this preconception, undermining local dynamics

and indigenous knowledge on the ground.

International development agencies as well as

scientific organizations operating in the domestic

level are quick to give the same conclusion about

the relationship between the local communities

of people and their natural environment (forests

and grasslands). The dominant understanding

within these development institutions is that local

communities are turning the forests into

savannahs, through massive deforestation

practices potentially extending the arid areas of

Sahel.

In the early 1990s, Melissa Leach and James

Fairhead went to Kissidougou Prefecture in the

Republic of Guinea in West Africa to find answers

to certain questions concerning deforestation.

Kissidougou was of strategic importance during

that time as it was situated in the middle of two

regions: drier areas of savannah to the north and

dense forests to the south. According to Leach

herself, Kissidougou portrayed a striking contrast

between the zones of grasslands and the pockets

of forests, making it interesting to explore the

way the environment was changing. In the

villages of Toly and Sandaya, they were out to

investigate and look for evidences to support the

assertion that farming, population, and

urbanization were putting an unbearable strain to

the forests. The village of Toly was located in the

forest zone, while Sandaya was in the savannahs.

As social anthropologists, they employed in depth

analysis to fully understand the interface between

the peoples and the forests. Through participant

observation, they lived in the villages long enough

for them to grasp the dynamics of the community

and the environment they lived in. In the film,

many interviews with key informants, who were

mostly village elders, were shown. They provided

vital information, which, little by little, shed light

into the problems and issues the anthropologists

went out to investigate.

However, initial findings by the researchers

showed exact contrary to the hypothesis of their

study. Instead of establishing facts that show how

the village community (Sandaya) contributed to

the degradation of the forests, the people even

claimed that they and their ancestors, who

settled in what was once an area of arid

grasslands, planted the trees which eventually

became forests. The researches then decided to

gather as many evidence to substantiate their

initial findings. They worked with local

researchers to conduct a study (COLA) on the

forests. Evidences started to show that indeed the

forests were manmade. Tree species not

indigenous to the area indicated that these were

perhaps introduced into the village by the people

themselves. The research was extended to cover

not only the forest per se but also the local

market and trading patterns of the people.

Information from elders in 30-40 villages

corroborated the same finding: the ancestors of

the present-day villagers created the forests

surrounding the communities. Documents from

archives were collected and scrutinized as well,

only to confirm what was already apparent.

Oral accounts for these researchers were still not

enough so they resorted to studying aerial and

satellite photographs of the area for the last 40-

year period. Latest photos also served to update

their findings. As regards the interpretations

made from the research findings, the researchers

participated in the daily work and activities of the

villagers, during the conduct of which they were

asked indirectly about their perceptions of their

forest environment and their farming practices.

Descriptions of how their farming and fishing

practices or other resource use have changed

served as indicators of environmental conditions.

Fairhead showed this clearly as he related how his

own experience of working with the village men

as they toiled the land provided a venue for

understanding the interaction between the

community and the landscape. He said that it was

during these occasions (and everything else in

between) that people came to talk openly and

freely about their opinion, which could serve as

vital inputs into their research interpretations.

On the other hand, scientists and policymakers

were more inclined to overlook the accounts of

local knowledge found on the ground. They would

rather listen to the landscape than to the

inhabitants. The anthropological research came

up with completely different findings. It was

established that the remaining forests found in

the savannah areas were not a product of

deforestation. The forests were not even there in

the first place. Aerial photographs showed the

changes in the areas of vegetation: forest cover

had increased in areas surrounding the peoples

places of settlements, while savannah eventually

encroached areas that were abandoned by the

villagers. This yielded to the conclusion that the

growth and wellbeing of the forest are very

closely linked to the people close by. This,

according to Fairhead, meant that in the

savannahs, more people doesnt necessarily

mean more degration undermining the

conventional assumption that people are natures

degraders. The more control and management

that communities have over the landscape

resulted to richer landscapes.

The quality of forests also reflected indigenous

knowledge and valuation of the forests that they

created and the lands that they managed. Human

intervention in the savannahs gave way to richer

land conditions supportive of forest biodiversity.

The forests served to protect the settlements

from bushfires which happened very often in the

grasslands. The forests also supported their ways

of farming. Farmers simply form mounds on the

land and bury compostable materials to fertilize

the soil. Crop rotation was performed to further

enrich the soil: rice during the first year, cassava

in the following year, and ground nuts after that.

This process enriched and softened the soil at the

same time. The land was being left uncultivated

for a period of ten years to allow the first trees to

grow and provide the foundation for younger

seedlings to germinate and develop until a new

forest is given birth to.

Villagers also intentionally burned areas earlier to

create barriers for greater bushfires and protect

plant species that served as their sources of food

and shade. Distinct plant characteristics were

familiar to the villagers and they used each

species for different purposes that support both

their community life as well as the surrounding

forests. White grasses were used for thatching

their roofs while long grasses were left as they

could later on convert into forests. Tree cuttings

used as fences would eventually grow to become

trees surviving several generations.

A different situation was taking place in the

village of Toly during that time. Forest areas,

which were likewise man-made, had expanded

into the savannahs thereby causing the grass

species used for thatching to decline. Peoples

farming techniques had to adapt to the changes

in the agricultural landscape. In the past, when

they were farming in the savannahs, preparing

the soil entailed uprooting the grass and burning

it. Recently, as the forests have already expanded

into the farming areas, soil preparation involved

cutting the undergrowth and felling trees and

burning the cleared area. The farmers claimed of

a certain way of burning the fields. When this

process was carried out correctly, the burning

process would enrich the soil.

Without prior knowledge of the history of these

forests, one would be quick to judge that the

practice of burning is an indiscriminate act of

destroying the forests. This practice of managing

lands have been easily misinterpreted and

misrepresented.

A report from the French colonists largely

misrepresented the practice of burning as

overexploitation of forests leading further into

savannization, with very few pockets of forests

left in the area. Scientists made the same

generalizations hence. Leach explained that

scientific experts have been convinced by what

they saw in the landscape without delving into

historical underpinnings of the phenomenon. As

scholars of natural sciences, they were not

inclined to look into historical data since they

perceived history as a distant discipline

insignificant in the study of forestry. The aerial

photographs were also left out. This

misrepresentation then became so deeply

entrenched that even schools portrayed the

practice as senseless destruction of the natural

vegetation.

The findings of the COLA study came as a shock to

development workers who continued to operate

under the conventional assumptions. As local

research collaborator Dominique Millimouno

explained, policy makers and development staff

were skeptic of their findings. Despite that,

people started paying attention and attitudes

began to change as well. Development workers

went out to validate their research discoveries

and they were able to come up with the same

conclusions: that the forests have indeed been

improving. The Forestry Department staff working

on the ground confirmed that the communities

and their interventions made possible the

existence and improvement of these forest

islands found in what were once wide savannahs.

However, higher level policy makers source of

knowledge remained under the monopoly of

international scientific and policy circles.

The ethnographic approach made significant

contributions in policy reforms especially in

development projects that concern people and

their environments. Researches such as those

conducted by Leach and Fairhead and other local

researchers made it possible for the phrase local

or indigenous knowledge systems to reach

development policy reports and discussions that

used to be the sole domain of strictly scientific

disciplines. Ethnography has proven particularly

useful in changing the outlook of development

staff who have been in constant interaction with

the people and their environment. The COLA

study had influenced this sector of the whole

development bureaucracy to make its own

investigation. Findings from the different

development projects opened the minds of

development workers of opposite situations in

the targeted areas, which render top-down

project implementation inapplicable, and

together with it the simplistic assumptions that

characterize their project beneficiaries. Although

higher level management continued to hold on to

these assumptions, apparent shifts in attitude

from their end was perhaps only a matter of time.

Anthropology, with its unique ability to bring to

the fore several questions that natural scientists

consider unimportant, plays a pivotal role in

shifting paradigms that guide development work.

The study in Kissidougou, teaches us that even

universal theories can be put into question, that

environmental narratives dont always end in

tragedy.

Leach revealed that parallel findings were

recently confirmed in different settings across

Africa. The study opens the possibility of giving

new meaning to natureone that allows people

their history. Most importantly, the

anthropological approach, when employed in

development research, can help prevent potential

tragedies from taking place in local settings

those which may be impacted by misguided

development projects that continue to disregard

local knowledge.

References

Hardin, G 1968, The tragedy of the commons, Science, 162,

pp. 1243-1248.

Cyrus Productions 1996, Second nature (documentary film),

with contributions by Leach, M, Fairhead, J & Millimouno, D.

You might also like

- Limbo: Blue-Collar Roots, White-Collar DreamsFrom EverandLimbo: Blue-Collar Roots, White-Collar DreamsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (37)

- BEAUTIFUL BROKENNESS: Redefine Your Beauty by Breaking Through Emotional Roadblocks, Elevating Your Mind with a Renewed Mindset, and Evolving in God's Divine PurposeFrom EverandBEAUTIFUL BROKENNESS: Redefine Your Beauty by Breaking Through Emotional Roadblocks, Elevating Your Mind with a Renewed Mindset, and Evolving in God's Divine PurposeNo ratings yet

- Black Girl, White School: Thriving, Surviving and No, You Can't Touch My HairFrom EverandBlack Girl, White School: Thriving, Surviving and No, You Can't Touch My HairNo ratings yet

- The Purple World: Healing the Harm in American Health CareFrom EverandThe Purple World: Healing the Harm in American Health CareNo ratings yet

- Book of Revelations: Divine Disclosures of Best Kept SecretsFrom EverandBook of Revelations: Divine Disclosures of Best Kept SecretsNo ratings yet

- Evangelical Postcolonial Conversations: Global Awakenings in Theology and PraxisFrom EverandEvangelical Postcolonial Conversations: Global Awakenings in Theology and PraxisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Inner City Public Schools Still Work: How One Principal's Life Is Living Proof!From EverandInner City Public Schools Still Work: How One Principal's Life Is Living Proof!No ratings yet

- HER AWAKENING: One Woman's Journey to Healing After DivorceFrom EverandHER AWAKENING: One Woman's Journey to Healing After DivorceNo ratings yet

- Who Will Speak for Me?: A Journey on a Path to Freedom from Emotional AbuseFrom EverandWho Will Speak for Me?: A Journey on a Path to Freedom from Emotional AbuseNo ratings yet

- Between the World and Me: by Ta-Nehisi Coates | Conversation StartersFrom EverandBetween the World and Me: by Ta-Nehisi Coates | Conversation StartersRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Be the One: Six True Stories of Teens Overcoming Hardship with HopeFrom EverandBe the One: Six True Stories of Teens Overcoming Hardship with HopeNo ratings yet

- War on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence by Ronan Farrow | Conversation StartersFrom EverandWar on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence by Ronan Farrow | Conversation StartersNo ratings yet

- Sibling Relationships in Childhood and Adolescence: Predictors and OutcomesFrom EverandSibling Relationships in Childhood and Adolescence: Predictors and OutcomesNo ratings yet

- Bourdieu, Habitus and Social Research: The Art of ApplicationFrom EverandBourdieu, Habitus and Social Research: The Art of ApplicationCristina CostaNo ratings yet

- Straight from the Heart I'm a Poet and Didn’t Even Know ItFrom EverandStraight from the Heart I'm a Poet and Didn’t Even Know ItNo ratings yet

- Happily Grey: Stories, Souvenirs, and Everyday Wonders from the Life In BetweenFrom EverandHappily Grey: Stories, Souvenirs, and Everyday Wonders from the Life In BetweenNo ratings yet

- Through a Therapist’s Eyes: Reunderstanding Emotions and Becoming Your Best SelfFrom EverandThrough a Therapist’s Eyes: Reunderstanding Emotions and Becoming Your Best SelfNo ratings yet

- The Man Who Changed His Skin: The Life and Work of John Howard GriffinFrom EverandThe Man Who Changed His Skin: The Life and Work of John Howard GriffinNo ratings yet

- Evolution Through Awareness: Transform your life and empower your mindFrom EverandEvolution Through Awareness: Transform your life and empower your mindNo ratings yet

- Lead To Change The World: The Mantra for Becoming A Happy and Successful Change MakerFrom EverandLead To Change The World: The Mantra for Becoming A Happy and Successful Change MakerNo ratings yet

- NORMAL Doesn't Live Here Anymore: An Inspiring Story of Hope for CaregiversFrom EverandNORMAL Doesn't Live Here Anymore: An Inspiring Story of Hope for CaregiversNo ratings yet

- An Affair Worth Remembering With Huntington’s Disease: Incurable Love & Intimacy During an Incurable IllnessFrom EverandAn Affair Worth Remembering With Huntington’s Disease: Incurable Love & Intimacy During an Incurable IllnessNo ratings yet

- The Godly Principle of Self-Interest: Steppingstone to Intra and Inter Racial HarmonyFrom EverandThe Godly Principle of Self-Interest: Steppingstone to Intra and Inter Racial HarmonyNo ratings yet

- The Fall and Rise of Women: How women can change the worldFrom EverandThe Fall and Rise of Women: How women can change the worldNo ratings yet

- Sex, Lies and Someone Else's Picture: An Author’S Personal Journey into the World of Internet DatingFrom EverandSex, Lies and Someone Else's Picture: An Author’S Personal Journey into the World of Internet DatingNo ratings yet

- Love Your Mother: 50 States, 50 Stories, and 50 Women United for Climate JusticeFrom EverandLove Your Mother: 50 States, 50 Stories, and 50 Women United for Climate JusticeNo ratings yet

- Choosing Single Parenthood: Stories from Solo Parents by ChoiceFrom EverandChoosing Single Parenthood: Stories from Solo Parents by ChoiceNo ratings yet

- Resetting: An Unplanned Journey of Love, Loss, and Living AgainFrom EverandResetting: An Unplanned Journey of Love, Loss, and Living AgainNo ratings yet

- Happy AF: Simple strategies to get unstuck, bounce back, and live your best lifeFrom EverandHappy AF: Simple strategies to get unstuck, bounce back, and live your best lifeNo ratings yet

- The Price of Paradise: The Costs of Inequality and a Vision for a More Equitable AmericaFrom EverandThe Price of Paradise: The Costs of Inequality and a Vision for a More Equitable AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Adventure Tourism: Latest Information, Global Trends, Impact On Local Economies, Market ChallengesDocument15 pagesAdventure Tourism: Latest Information, Global Trends, Impact On Local Economies, Market ChallengesKim Dyan Calderon100% (1)

- Post Development To Post SelfDocument5 pagesPost Development To Post SelfKim Dyan CalderonNo ratings yet

- Echo-Sharing On APO Agrotourism Development and Marketing Workshop Bali Indonesia 2013Document68 pagesEcho-Sharing On APO Agrotourism Development and Marketing Workshop Bali Indonesia 2013Kim Dyan CalderonNo ratings yet

- WOW Efforts 2013-14Document7 pagesWOW Efforts 2013-14Kim Dyan CalderonNo ratings yet

- WallthicknessDocument1 pageWallthicknessGabriela MotaNo ratings yet

- Num Sheet 1Document1 pageNum Sheet 1Abinash MohantyNo ratings yet

- Design Calculation FOR Rigid Pavement/RoadDocument5 pagesDesign Calculation FOR Rigid Pavement/RoadghansaNo ratings yet

- Column Buckling TestDocument8 pagesColumn Buckling TestWiy GuomNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Production and Cost: Chapter FourDocument32 pagesThe Theory of Production and Cost: Chapter FourOromay Elias100% (1)

- Reading Proficiency Level of Students: Basis For Reading Intervention ProgramDocument13 pagesReading Proficiency Level of Students: Basis For Reading Intervention ProgramSONY JOY QUINTONo ratings yet

- U2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciDocument6 pagesU2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciELVIN MANUEL CONDOR CERVANTESNo ratings yet

- Planetary Yogas in Astrology: O.P.Verma, IndiaDocument7 pagesPlanetary Yogas in Astrology: O.P.Verma, IndiaSaptarishisAstrology50% (2)

- The Invisible SunDocument7 pagesThe Invisible SunJay Alfred100% (1)

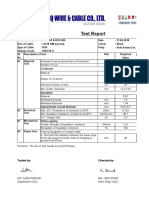

- Test Report: Tested By-Checked byDocument12 pagesTest Report: Tested By-Checked byjamilNo ratings yet

- Group 2 - BSCE1 3 - Formal Lab Report#6 - CET 0122.1 11 2Document5 pagesGroup 2 - BSCE1 3 - Formal Lab Report#6 - CET 0122.1 11 2John Eazer FranciscoNo ratings yet

- SR# Call Type A-Party B-Party Date & Time Duration Cell ID ImeiDocument12 pagesSR# Call Type A-Party B-Party Date & Time Duration Cell ID ImeiSaifullah BalochNo ratings yet

- The Neuroscience of Helmholtz and The Theories of Johannes Muèller Part 2: Sensation and PerceptionDocument22 pagesThe Neuroscience of Helmholtz and The Theories of Johannes Muèller Part 2: Sensation and PerceptionCrystal JenningsNo ratings yet

- AZ 103T00A ENU TrainerHandbook PDFDocument403 pagesAZ 103T00A ENU TrainerHandbook PDFlongvietmt100% (2)

- Hayek - Planning, Science, and Freedom (1941)Document5 pagesHayek - Planning, Science, and Freedom (1941)Robert Wenzel100% (1)

- Analysis and Design of Well FoundationDocument40 pagesAnalysis and Design of Well Foundationdhanabal100% (1)

- A. Premise Vs Conclusion NotesDocument8 pagesA. Premise Vs Conclusion NotesEmma PreciousNo ratings yet

- TIB Bwpluginrestjson 2.1.0 ReadmeDocument2 pagesTIB Bwpluginrestjson 2.1.0 ReadmemarcmariehenriNo ratings yet

- Case Paul Foster Highlights of TarotDocument76 pagesCase Paul Foster Highlights of TarotTraditionaltarot100% (6)

- Efektifitas Terapi Musik Klasik Terhadap Penurunan Tingkat HalusinasiDocument9 pagesEfektifitas Terapi Musik Klasik Terhadap Penurunan Tingkat HalusinasiAnis RahmaNo ratings yet

- The Practice Book - Doing Passivation ProcessDocument22 pagesThe Practice Book - Doing Passivation ProcessNikos VrettakosNo ratings yet

- Apps Android StudioDocument12 pagesApps Android StudioDaniel AlcocerNo ratings yet

- Answer:: Exercise-IDocument15 pagesAnswer:: Exercise-IAishika NagNo ratings yet

- 8 Lesson 13 Viking FranceDocument2 pages8 Lesson 13 Viking Franceapi-332379661No ratings yet

- RV900S - IB - Series 3Document28 pagesRV900S - IB - Series 3GA LewisNo ratings yet

- Corometrics 170 Series BrochureDocument3 pagesCorometrics 170 Series BrochureCesar MolanoNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Harmonic Measurement Study ProcedureDocument13 pagesRisk Assessment For Harmonic Measurement Study ProcedureAnandu AshokanNo ratings yet

- IDL6543 ModuleRubricDocument2 pagesIDL6543 ModuleRubricSteiner MarisNo ratings yet

- Electronics 12 00811Document11 pagesElectronics 12 00811Amber MishraNo ratings yet

- On The Importance of Learning Statistics For Psychology StudentsDocument2 pagesOn The Importance of Learning Statistics For Psychology StudentsMadison HartfieldNo ratings yet