Professional Documents

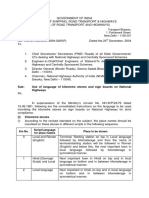

Culture Documents

SEEP Vol.23 No.1 Winter 2003

Uploaded by

segalcenterOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SEEP Vol.23 No.1 Winter 2003

Uploaded by

segalcenterCopyright:

Available Formats

volume 23, no.

l

Winter 2003

SEEP (ISSN # 1047-0019) is a publication of the Institute for Contemporary

East European Drama and Theatre under the auspices of the Martin E. Segal

Theatre Center. The Institute is at The City University of New York Graduate

Center, 365 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. All subscription requests

and submissions should be addressed to Slavic and East European Peiformance:

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center, Theatre Program, The City University of New

York Graduate Center, 365 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309.

EDITOR

Daniel Gerould

MANAGING EDITOR

Kurt Taroff

EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS

Kimon Keramidas

Melissa Johnson

CIRCULATION MANAGER

Jill Stevenson

ASSIST ANT CIRCULATION MANAGER

Mark Ginsberg

ADVISORY BOARD

Edwin Wilson, Chair

Marvin Carlson Alma Law

Martha W. Coigney Stuart Liebman

Leo Hecht Laurence Senelick

Allen J. Kuharski

SEEP has a very liberal reprinting policy. Journals and newsletters that desire to

reproduce articles, reviews, and other materials that have appeared in SEEP may do

so, as long as the following provisions are met:

a. Permission to reprint the article must be requested from SEEP in writing before

the fact;

b. Credit to SEEP must be given in the reprint;

Two copies of the publication in which the reprinted material has appeared must be

furnished to the Editors of SEEP immediately upon publication.

MARTIN E. SEGAL THEATRE CENTER

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Edwin Wilson

DIRECTOR

James Patrick

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications are supported by generous grants from

the Lucille Lortel Chair in Theatre and the Sidney E. Cohn Chair in Theatre in the

Ph.D. Program in Theatre at the City University of New York.

Copyright 2003 Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

2

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

Editorial Policy

From the Editor

Events

Books Received

ARTICLES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

"The Avram Goldfaden International Theatre

Festival in Iasi, Romania"

Beate Hein Bennett

"Jerzy Grotowski's Bright Alley"

Magdalena Hasiuk

"Nord-Ost: Tragic Nights in the Theatre"

Maria Ignatieva

"Siobodan Snajder: Playwright"

Milos Lazin

"Mickiewicz's Ballads and Romances on the

Contemporary Polish Stage"

Eileen Kiajewski

REVIEWS

5

6

7

11

12

24

34

38

46

"A Month in Another Country: 56

After Turgenev, By Friel"

Laurence Senelick

"Chekhov in Toronto for Russians and Non-Russians 60

Y ana Meerzon

3

"Fool's Mass: Theatre Group Dzieci at La Mama"

Edmund Lingan

"Janusz Glowacki's The Fourth Sister

at the Vineyard Theatre"

Meghan Duffy

Contributors

65

71

76

4

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No.1

EDITORIAL POLICY

Manuscripts in the following categories are solicited: articles of no

more than 2,500 words, performance and film reviews, and bibliographies.

Please bear in mind that all submissions must concern themselves either

with contemporary materials on Slavic and East European theatre, drama

and film, or with new approaches to older materials in recently published

works, or new performances of older plays. In other words, we welcome

submissions reviewing innovative performances of Gogo! but we cannot use

original articles discussing Gogo! as a playwright.

Although we welcome translations of articles and reviews from

foreign publications, we do require copyright release statements. We will

also gladly publish announcements of special events and anything else

which may be of interest to our discipline. All submissions are refereed.

All submissions must be typed double-spaced and carefully

proofread. The Chicago Manual if Style should be followed. Trans-literations

should follow the Library of Congress system. Articles should be submitted

on computer disk, as Word 97 Documents for Windows and a hard copy of

the article should be included. Photographs are recommended for all

reviews. All articles should be sent to the attention of Slavic and East

European PeJformance, c/ o Martin E. Segal Theatre Center, The City

University of New York Graduate Center, 365 5th Avenue, New York, NY

10016-4309. Submissions will be evaluated, and authors will be notified

after approximately four weeks.

You may obtain more information about Slavic and East European

Peiformance by visiting out website at http//web.gc.cuny.edu/mestc. Email

inquiries may be addressed to SEEP@gc.cuny.edu.

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Journals are available online from

ProQ!lest Information and Learning as abstracts via the ProQuest

information service and the International Index to the Performing Arts.

www.il.proquest.com

5

FROM THE EDITOR

Our Winter issue, Volume 23, No. I, opens with two articles that

are concerned with the search for roots, as contemporary Eastern European

theatre seeks to define itself. Beate Hein Bennett explores the sources of

Yiddish theatre in Romania in her article about the Avram Goldfaden

International Theatre Festival in Iasi, and Magdalena Hasiuk looks at Jerzy

Grotowski's Paratheatrical Activities and Theatre of Sources, the second part

of an on-going project devoted to the study of the past and present of

Grotowski's Theatrical Research. With this article, we commemorate the

seventieth anniversary of Grotowski's birth. Maria Ignatieva reports from

Moscow on the tragic history of Nord-Ost and the play's subsequent re-

opening. Milos Lazin gives a biographical sketch of the Croatian playwright

Slobodan Snajder and looks at his work in the theatre. Eileen Krajewski

explores how Adam Mickiewicz's Ballads and Romances have been

interpreted on the contemporary Polish stage.

In our section devoted to reviews, Laurence Senelick examines

Brian Friel's version of Turgenev's Month in the Country, Yana Meerzon

discusses two Chekhov productions in Toronto, Ed Lingan considers the

Polish ancestry of Theatre Group Dzieci's Fool's Mass, and Meghan Duffy

finds the post-Chekhovian in Janusz Glowacki's Fourth Sister.

* * * * * *

Many Czech theatres are still recovering from the damages caused

by the catastrophic floods of 2002. SEEP has received the following

information about rebuilding. The AURA-PONT Agency, with the Alfred

Radok Foundation, the Association of Professional Theatres of the Czech

Republic and Theatre Institute Prague, has started a charitable collection, the

proceeds of which will be used for the reconstruction of the flooded and

damaged Czech theatres. They can be contacted at: Aura-Pont, divadelnf a

literarnf agentura, spol. s.r.o., Radliclci 99, ISO 00 Praha 5, tel. +420 2SISS

4938, +420 2SISS 3992, fax: +420 2SISS 0207, email: zaplavy@aura-

pont.cz, www.theatre.cz

6

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

STAGE PRODUCTIONS

New York

EVENTS

The Manhattan School of Music presented The Seagull, an opera

composed by Thomas Pasatieri with a libretto by Kenward Elmslie based on

Chekhov's play. Directed by Mark Harrison, and conducted by David

Gilbert, performances were held on December 11, 13 and 15, 2002.

Theatre Group Dzieci presented The Devils ofLoudun, an adaptation

of the historical novel by Aldous Huxley, at La Mama's Annex Theatre from

January 2 to 19. Theatre Group Dzieci also performed Fool's Mass, a peasant

masque dedicated to Jerzy Grotowski, on January 5, 12 and 19, and taught

a paratheatrical workshop titled Ritual and Transformation on January 13.

The Jean Cocteau Repertory presented Chekhov's Uncle Vanya at

the Bouwerie Lane Theatre. The production, translated by John Murrell,

directed by Eve Adamson, ran from January 10 to March 2.

From February 6 to March 2, Another Theatre Company

performed Chekhov's The Seagull, adapted and directed by Michael Kier, at

the Trilogy Theatre.

The Wooster Group restaged Brace Up!, their interpretation of the

Paul Schmidt translation of Anton Chekhov's Three Sisters. Performances

ran from February 19 to March 16 at St. Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn.

The Czech-American Marionette Theatre presented Twe{fth Night,

directed by Vft Horejs, from March 6 to 16.

The Classical Theatre of Harlem will present Stanislaw Ignacy

Witkiewicz's The Crazy Locomotive, directed by Christopher McElroen, from

March 28 to April20.

7

STAGE PRODUCTIONS

United States

The Polish experimental theatre company Gardzienice performed

Metamorphosis, or The Golden Ass according to Lucius Apuleius on March 8 at

the Getty Center in Los Angeles.

STAGE PRODUCTIONS

International

Viacheslav Misin and Alexander Shaburov of The Blue Noses

Group from Siberia, Russia performed in London at Toynbee Studios on

March 1. They performed a selection of short performance works from the

series The Blue Noses, which were developed as part of a burlesque art festival

celebrating their isolation from the outside world.

FILM

New York

MOMA presented four early films by Hungarian filmmaker Bela

Tarr in a series entitled Bela Tarr: First Steps of a journey. The screening

schedule was as follows:

Oszi almanach (Almanac of Fall, 1985), February 20, 22.

Csalddu tiizflszek (Family Nest, 1978), February 20.

Szabadgyalog (77Je Outsider, 1981), February 21.

Panelkapcsolat (The Prefab People, 1982), February 21.

MOMA also screened the following three works by Eastern

European filmmakers at the Gramercy Theatre:

8

The Red and the White (1967) by Miklos Jancs6 (Hungary), January

31.

Paradox Lake (2002) by Przemyslaw Reut (Poland), February 10

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

Korczak (1990) by Andrzej Wajda (Poland), February 13.

OTHER EVENTS

New York

The 92nd Street Y presented The Art of the Fugitive: The Paradoxical

Life of Paul Celan, in a co-production with Nine Circles Chamber Theatre.

The performance, which interweaves the Romanian poet's poetry with

music, took place on January 13.

The Czech Center New York, The Immigrants' Theatre Project, and

The Theatre Institute, Prague presented New Czech Plays: Staged Readings in

Translation at the New York Theatre Workshop. The performances and

dates were as follows:

The Girls' Room (Pokojicek), by Jan Antonin Pitinsey, directed by

Marcy Arlin, January 13.

Tales of Common Insanity (PHblhy obycejniho fflenstvt), by Petr

Zelenka, directed by Gwynn MacDonald, February 24.

I Promised Freddy: A Collector's Unbelievable Story (Slibil jsem to

Freddymu), by Egon L. Tobias, directed by Kaipo Schwab, March

24.

It's Time for IT to Change (je na case, aby se TO zmlnilo), by Egon L.

Tobias, directed by Jaye Austin-Williams, March 24.

Minach, by Iva Volankova, directed by Marcy Arlin, April28.

The CUNY Graduate Center, in collaboration with the Martin E.

Segal Theatre Center, hosted a lecture by Macedonian theatre director and

Professor of Acting and Directing Slobodan Unkovski (see SEEP Vol. 21,

No. 1, Winter 2001) on January 24. Unkovski discussed Einstein in Athens,

the adaptation of Alan Lightman's Einstein's Dreams for the National Theatre

in Greece.

9

In Masterpieces of the Russian Underground in late January at the

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, pianist Vladimir Feltsman and

musicians from the Chamber Music Society presented a number of

important but lesser known works by composers such as Shostakovich,

Schnittke, Andre Volkonsky and Nicolai Karentikov.

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts presented a

series of readings, The Plays if Anton Chekhov: Translations fry Michael Frayn,

on March 10. Included were scenes from Frayn's translations of The Cherry

Orchard, The Seagull, The Sneeze, The Three Sisters, Uncle Va1rya, and Wild

Honey, directed by Lawrence Sacharow.

Compiled by Kimon Keramidas

10

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

BOOKS RECEIVED

Grossman, Elwira M., ed. Studies in Language, Literature, and Cultural

Mythology in Poland: Investigating "The Other." Slavic Studies, Vol. 7.

Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2002. 327 pages. A collection of essays

dedicated to the memory of Donald P.A. Pirie. Chapter 2, "Rethinking

Representations of Otherness in Drama and Theatre," includes Halina

Filipowicz, "Othering the Kosciuszko Uprising: Women as Problem in

Polish Insurgent Discourse"; Daniel Gerould, "Witkacy's Unity in

Plurality-a World of Otherness"; Paul Allain, "Gardzienice's Performance of

Otherness"; Tamara Trojanowska, "Individuality and Otherness: Reading

Rozewicz Performing Kafka"; Agnieszka Skolasinska, "Deconstructing the

Polish Tradition in Tadeusz Rozewicz's Mariage Blanc." Includes a

photograph of Donald P.A. Pirie and a bibliography of major works written

and edited by him, as well as an index.

Lebedev, Evgenii. Velikii litsedei: Rasskazy, dnevniki, vospominaniya.

Moscow: Centrpoligraf, 2002. 522 pages. Includes stories, essays, sketches,

correspondence, reminiscence, as well as a chronology of the life and work

of Lebedev (1917-1997), bibliography, and many photographs.

Skwara, Marta, ed. Witkary w Polsce i na fwiecie. (Szczecin: Uniwersytet

Szczecinski, 2000). 456 pages. A collection of essays, growing out of an

academic conference held in Szczecin, September 15-18, 1999, and

dedicated to the memory of Anna Micinska. Includes 31 essays, 5 in

English, 26 in Polish. Also included are summaries in English and Polish, a

dictionary of the authors, an index and a list of the academic sessions.

Tabakov, Oleg. Paradoks ob aktere. Moscow: Centrpoligraf, 1999. 379

pages.

"Witkacy." Pamiflnik Literacki, Vol. XCIII, No. 4. 2002. 276 pages.

Contains 15 articles and reviews about Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz and his

work.

11

THE AVRAM GOLDFADEN INTERNATIONAL

THEATRE FESTIVAL IN IASI, ROMANIA

Beate Hein Bennett

"When a city is destroyed, you can

gather the bricks and put the buildings back together; but how do you

reconstruct a culture and a language once it has been destroyed?" (Moshe

Yassur in Iasi, October 2002)

"We will leave some traces, for we are

people and not cities." (OLD MAN in Eugene lonesco's The Chairs, 1952)

In October 2002 the National Theatre Vasile Alecsandri invited

theatre artists and scholars from Romania, Israel, Germany, and the United

States to Iasi, Romania, a major city in the northeastern province of

Moldavia, for four days, October 15 to 18, on the occasion of the First

International Theatre Festival honoring Avram Goldfaden, the founder of

Yiddish theatre. Four full theatre productions (three of them in Yiddish), a

workshop production, a Klezmer concert with a combined group of German

and Roma musicians, seminars on the history of Yiddish theatre, theatre

workshops, press conferences, commemorations, tours of the city, and even

a fashion show by a very imaginative local designer filled the days and

evenings. All events and the theatre performances were well attended by

visitors and local audiences who followed the Yiddish language with the

help of simultaneous translations provided through headphones.

In October 1876, Avram Goldfaden wrote a letter to the singer

Moise Finkel containing what might be considered the Auftakt to the

Yiddish theatre:

12

Due to the fact that I am in Iasi at the moment ... at the

general request I've decided to put together a troupe with the very

best artists which I intend to organize in an European manner in

order for it to become a serious institution. Here, in lasi, will soon

be set up a permanent Jewish theatre that I was asked to manage ..

. . At the same time, I will continue writing new plays for this

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

theatre that will be unique in the world ... That is why I hope that,

when you receive this letter, you won't think long and you will get

here right away. Next to me, you will be here warmer than

anywhere else. We have performed in Simen Mark's garden. The

tickets were sold starting at 3 marks and 50 cents. There were never

so many spectators since the beginning of the garden ... I

That was the beginning of the Yiddish theatre, the Pomul Verde

(The Green Tree), as it came to be known, in Simen Mark's wine garden of

the same name. According to Nahma Sandrow "the story of how Goldfaden

actually came to found a Yiddish theatre in Jassy [Iasi] in 1876 has several

versions. "2 One of the more colorful ones is reported by a friend with whom

Goldfaden stayed in Iasi, where he originally wanted to start a Yiddish-

language newspaper. The friend's wife asked why he would want to start

another newspaper when the editor of the one existing Yiddish newspaper

in Romania "already starves to death seven times a day." And then she

planted the idea: "Listen to me: Jews need a theatre-that's what you should

do. Your sketch in Thejewess [one ofGoldfaden's popular ballads] was like

a play. Put it on, so we'll have a Yiddish theatre, a theatre like other people

have ... "

Starting at that point, Goldfaden, who is called the Father of

Yiddish theatre, embarked on a venture that eventually came to full bloom

in New York City, and, some would contend, in Hollywood. He himself was

not to profit much from his eventual worldwide popularity; he remained

poor, even though by the time he died in 1907 some thirty thousand

admirers followed his bier to Washington Cemetery in Brooklyn. However,

the theatre he had created found emulators and enthusiasts all over the

world. Yiddish theatre troupes were founded; the actors gained fame and

fortune; and, as Yiddish-speaking secular Jews had settled in all parts of the

world, there were ready-made audiences almost everywhere, except in Israel,

where Yiddish was associated by the native born sabras with the impotence

of the six million killed in the Holocaust and therefore largely rejected from

the official Hebrew culture. This, however, is another story, but it is worth

remembering the struggle which Yiddish-speaking survivors, and especially

actors, faced in their newly founded homeland.

Iasi is a university town with a well-known music conservatory

across the street from the National Theatre; therefore a good number of

young people attended the performances, and they responded with genuine

13

14

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

interest and excitement. The support for this event came from multiple

sources. Since Iasi is the capital of the province of Moldavia, and one of

Romania's oldest and the second-largest city after Bucharest, it is also the

seat of several foreign consulates and councils; thus the local and regional

institutions as well as the French, British, and German cultural centers were

partners. The Romanian Ministry of Culture supported the National

Theatre in its organizational efforts, and financial sponsorship from abroad,

notably Israel, enabled the full participation of the Israeli company

Yiddishpiel, which came from Tel Aviv with about thirty-five actors, some

of them veterans of the Pomul Verde in the late 1940s and 50s.

An institution of particular merit contributed two fully mounted

productions; the Teatrul Evreiesc de Stat (T.E.S), the Jewish State Theatre

from Bucharest, is one of the few state supported Jewish theatres outside

Israel. This theatre is a historical phenomenon; it was known during World

War II as Baraseum and from 1941 to 1944 continued to play a Jewish

repertoire with Jewish actors, albeit in Romanian, during the height of the

Holocaust.3 That is also another story and reflects only one of the many

complicated paradoxes in Romanian cultural history.

On the first day, a new sculpture marking the spot of the Pomul

Verde was officially unveiled in the park across from the National Theatre;

a bust of Avram Goldfaden had been erected nearby some years earlier. The

speeches by the Minister of Culture of Romania, the Ambassador of Israel

to Romania, the President of the Jewish Council, the Mayor of Iasi,

representatives of the community, and the cultural, artistic, and political

arenas held the assembled crowd by their emotional impact despite or

perhaps because of their multilinguality (Romanian, Yiddish, Hebrew,

English, French). A common refrain was the need for cultural encounters

and connections as symbolized by the Festival in this fractured world.

The first play, Avram Goldfaden's satire Zvei Kuni-Leml, was

presented by the Yiddishpiel &om Tel Aviv. Under the direction of Motti

Averbuch with choreographic and clowning assistance by Golan Shlomi,

young Israeli actors for whom Yiddish is a foreign language gave a broadly

comic circus-style rendering of a popular farce. The cast, dressed in a bright

mix of costume styles in bold seventies colors, literally bounded across the

stage over, through, and around a skeletal set, both designed by Ben-AriJosi.

The second and third play presentations were by T.E.S., which

maintains an active repertory of Yiddish language plays throughout the year

in its home theatre in Bucharest. For most of the ensemble of actors,

15

especially the young ones, Yiddish is a foreign language. (However, it is not

unusual for actors from European countries, especially Eastern and

Northern Europe, to perform in languages other than their native tongue.)

In order to expand the repertory of plays in Yiddish, T.E.S. frequently

presents plays from other languages translated into Yiddish (also

simultaneously translated via headphones into Romanian for the benefit of

the majority of the audience). Thus The Book of Ruth by contemporary

Argentinean/ American playwright Mario Diament and The Merchant by

Arnold Wesker were both presented in Yiddish with simultaneous

headphone translations in Romanian.

The Book of Ruth, translated into Yiddish and directed by Moshe

Y assur, was a particularly poignant and evocative production. The play is a

web of memories threading and weaving their way out of Ruth's

consciousness. Ruth has come towards the end of her life and finds that her

mind, like her attic, is a store of rejected bits and pieces of her life. In a fluid

poetic structure with four Ruths at different stages, the play interweaves

stations in her life. Shuttling from Poland in the 1930s when she was a

young girl full of artistic ambitions and in love with Max, a socialist, to her

forced (by her mother) emigration and indifferent marriage in Argentina to

Boris, a childhood friend become entrepreneur, to her love affair with

Alfredo, her children, Boris's failure in business, the play culminates in the

ruminations of her losses; the loss of her family in the Holocaust and her

own alienation and failure in achieving her dreams.

The primary Ruth was played with graceful charm and beauty by

Leonie W aldman-Eliad. (In September 1972 Harvey Lichtenstein brought

T.E.S to the Brooklyn Academy of Music where Waldman-Eliad played Lea

in The Dybbuk to great critical acclaim.)

4

She was surrounded by an

ensemble of players whose sensitive interaction, fine character delineation,

and calibrated voices created a moving piece of theatrical chamber music.

The setting and costumes designed by Irina Solomon, with lighting by

Eugen Ciocan and sound effects by Vasile Manta, supported the delicate

structure of the play and allowed the characters to emerge literally from the

cluttered emanations of Ruth's memory.

Moshe Yassur's economic translation and exacting direction

breathed an authentic life into this play, and it seemed uncannily to have

been made for that theatre, that stage, and Iasi at this time. Perhaps this

chemistry was not entirely an accident. Yassur was born in Iasi in 1934,

survived a pogrom as a child of almost seven, and acted as a child actor after

16

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

......

'--l

Leonie W aldman-Eliad and Nicolae Calu Garitsa in The Book

of Ruth by Mario Diament, directed by Moshe Y assur

World War II on the stages of the Pomul Verde and the National Theatre

until his own emigration to Israel in 1950.

The next evening T.E.S. performed Arnold Wesker's The Merchant

in Yiddish, under the title Shylock, directed by Grigore Gonta and starring

Maia Morgenstern as Portia, Constantin Dinulescu as Shylock, Cornel

Ciupercescu as Antonio, and most of the same ensemble that distinguished

itself in The Book of Ruth. Elegantly dressed in Venetian Renaissance

costumes by Luana Dragoescu and in a simple setting suggestive of locale,

the company presented Wesker's discourse on the social machinations of

racial prejudice as an impassioned appeal.

The third and final production of the Festival was Isaac Bashevis

Singer's story, Teibele and her Demon, adapted for the stage by Eve Friedman

and directed by the Canadian/Romanian Alexander Hausvater with the

company of the National Theatre Vasile Alecsandri Iasi. It was played in

Romanian. Blurring the boundaries between the various realities of theatre,

i.e. actor/character, rehearsal/performance, stage/theatre, Hausvater

manipulated the audience into becoming participants at the event.

The theatre lobby was made into the dressing room where actors

and audience intermingled. At a certain point the audience is invited to

enter the theatre through a narrow black veiled dark passage, obviously

alluding to a sexual passage. This set the tone for a very physical

performance in which a chorus of yeshiva boys alternately cling to and

climb the walls of their school womb, while Teibele undergoes the

paroxysms of rape by her Demon, the poor cabbalist Alchonon in the mask

of Hurmizah.

The highly expressionistic style demanded a truly awesome

athleticism of the performers; the emphasis on verticality in space and

movement, the highly sensual choreography executed with vertiginous

speed brought to the surface the immanent violence of sexual repression that

underlies the story. This was at the expense of its more delicate overtones.

The performances, especially of Do ina Deleanu as T eibele, were truly

astounding in their dynamic power. The director juxtaposed the violent

Teibele/Demon scenes with very playful loving scenes between Teibele and

her woman friend, Genendel.

The set design by Guido T ondino and Axenti Marfa played on the

oppositional chiaroscuro of passion by juxtaposing the poor confines of a

square wooden room (half is Teibele's room and half is the area of the

cabbalist's study) with Nature in the form of a fantastic tree that arches over

18

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

and high above Teibele; at the end the boys climb, naked as god made them,

into that tree. As a whole, the production is courageous and visually very

beautiful, but one may argue about the caricature of the sex-starved Hasid.

A very powerful one-woman show, Tata Are Lagar (My Father

Owns a Camp), inspired by the novel Nighifather by Carl Friedman and

directed by Erwin Simensen, a fifth year directing student at UATC

Bucharest, was shown in the studio space of the National Theatre in the

afternoon. The young actress Raluca Oprea together with composer Radu

Captari and musician Octavian Mardari presented a harrowing text that

delves into the soul of the children of Holocaust perpetrators once they

come face to face with the reality of their parents' dark past. Sitting together

with survivors of generations of political horror, old and young, and

listening to this solitary voice recounting her descent into memory was

deeply moving.

The previous afternoon a diversion of a light note brought a large

crowd to the main stage of the National Theatre. Originally, the whole

Megille Band from the Rocktheatre Dresden, Germany was to come.

However, only the bandleader, Detlef Hutschenreuter, and one young

saxophonist were able to come, but they received expert musical support

from a local Rom a band. The sight of Germans and gypsies playing Jewish

klezmer tunes on the stage of the lush Beaux-Arts National Theatre in Iasi,

Romania, to an audience of Romanians, Israelis, and Americans who sing

along has to be construed as a sign of civilizational progress, albeit limited

in time and space.

Workshops and lectures open to the public provided various

professional and historical insights. The eminent historian of Yiddish

theatre, Nahma Sandrow, who had come from New York, gave an overview

of Avram Goldfaden's contributions to Yiddish secular culture and theatre.

It was her first trip to Iasi, "the source," and she felt she had come to

"paradise." Moti Sandak from Israel demonstrated the launching of a new

global website, "All About Jewish Theatre," intended to be a clearinghouse

of information regarding the most varied relevant activities. Acting

workshops, one, for example, by Moshe Yassur with acting students from

the local conservatory, provided a glimpse into the work world of actor

training.

For four days, there were many opportunities for participants to

exchange ideas, impressions, and stories, although the preponderant taste by

the organizers for so-called press conferences tended to stifle the spontaneity

19

20

Moshe Yassur, director of The Book of Ruth, standing in front

of the National Theatre Vasile Alecsandri, lasi

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

of such exchanges. On the other hand, a forum was provided to speak

publicly about the accomplishments and anxieties that beset such unique

institutions as T.E.S. and Yiddishpiel. The directors, Harry Eliad of T.E.S.

and Shmuel Atzmon of Yiddishpiel, both spoke about the difficulty of

maintaining a company that plays in Yiddish to an audience whose first-

hand knowledge of the language and its attendant culture is diminishing or

non-existent. They also talked about the difficulty of finding a suitable

repertory and being able to compete with regular theatres for funding their

institutions. And they talked about overcoming animosity, if not latent or

open anti-Semitism, whose ominous signs are appearing again all over

Europe.

One of the most memorable events was a reception for the Festival

guests at the Jewish Community Center followed by a visit to the sole

surviving synagogue of more than one hundred before World War II. We

were welcomed to a lovely townhouse where food and drink awaited us. As

I looked around and saw the Romanian actors from T.E.S. and the Israeli

actors from Yiddishpiel, some young, some old, like Yaacov Alperin now in

his 80s, who played with the Pomul Verde in the late 1940s, standing

together, speaking and listening to a melange of Yiddish, Romanian,

Hebrew, and English, laughing with each other, I was keenly aware of the

special chemistry this moment had for all- it was a historic moment.

The concerted effort to bring about an International Theatre

Festival centered on Yiddish theatre in a city whose formerly thriving Jewish

community has been largely destroyed by the Holocaust and emigration

must be seen in historical perspective. While this Festival in 2002 was not

the first time that Avram Goldfaden was honored in Iasi as the "father" of

the Yiddish theatre, it differed in its aspiration to break beyond national

boundaries. In 1976 the National Theatre in Iasi celebrated its hundredth

anniversary by honoring Goldfaden with a T.E.S. production in Yiddish,

Firul de Aur (Golden Thread) by Israil Bercovici, with music by Avram

Goldfaden. The present general director of the National Theatre Vasile

Alecsandri Iasi, loan Holban, who spearheaded the 2002 event and who is

himself a literary scholar, clearly intends to cultivate a cultural legacy that

has contributed so much to the multicultural society that has always

constituted Romania. In a time when Romania once more is engaged in a

noisy discourse over cultural identity after a bloody revolution and

significant constitutional changes, and when chauvinistic voices for a

unicultural definition of identity are strident, it takes courage to undertake

21

such a public act of historical recovery.

Moldavia, like its neighboring regions, Bukovina to the north and

Transylvania to the west, has been for centuries home to a variety of ethnic

groups and languages. lasi, whose population in the 1920s and 30s was close

to fifty percent Jewish with a high proportion of students able to attend the

university since the emancipation of Jews in 1919, became a hotbed of anti-

Semitism which culminated in June 1941 in one of the worst pogroms

during World War II. Under the combined terror of the homegrown fascist

Iron Guard (also known as the Legion of the Archangel Michael), and the

Dictator Antonescu who allied himself with the German Nazi regime in its

campaign against Stalin's Soviet Russia, Iasi's Jewish population was

deported, killed, and suffered atrocious deprivations and degradation.s

The real dimension of the destruction became painfully palpable to

me as I visited the Jewish cemetery of Iasi. Situated on top of a long hill

overlooking the beautiful valley and vineyards that surround Iasi, the place

tells the full story. Rows upon rows of old sculptured grave stones speak of

a perhaps comfortable existence for generations; rows upon rows of white

crosses with the same family names of young men in their twenties tell the

story of the enormous losses to World War I-whenJews were drafted before

they even had citizenship. Adjacent to that field under the linden trees,

somewhat aside, and facing the Galata Monastery across the valley, we come

to four ominous rows of huge cement sarcophagi descending toward a stone

triptych. This is the mass grave for the eight to thirteen thousand killed in

the night of June 28/29, 1941 during the pogrom-the exact number could

never be established. I was grateful to the little white goat grazing in front of

the entrance in that it brought me back to the life around me, the new-found

friends from the Festival, the theatre artists who work to maintain the

creative spark and dare to kindle memory against so many odds. After all,

the community of spirit which theatre ultimately sponsors in all participants

dominated the events in a concrete way. Theatre is indeed memory work,

as Marvin Carlson elucidates in The Haunted Stage; this was never as apparent

to me as in the presence of actors and audiences who came together to evoke

the spirit of a nearly extinct culture and language and imbue it with life-

blood.

22

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

NOTES

1 Q!Ioted in the program notes for the Avram Goldfaden International

Theatre Festival, October 15-18, 2002.

2 Nahma Sandrow, Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater (New

York: Harper & Row, 1977). I am indebted to this immensely readable book

for the Goldfaden anecdotes.

3 Israil Bercovici, 0 sutd de ani de teatru evreiesc in Romania, editie revizuita si

adaugita de Constantin Maciuca (Bucuresti: Editura Integral, 1998). This

historical source book (One Hundred Years of jewish Theatre in Romania)

includes a detailed year-by-year account from 1876 until1997 of the Pomul

Verde, the T.E.S. Iasi, and the T.E.S. Bucharest.

4 Bercovici, p. 231.

5 For historical background I am indebted to two scholarly works: Irina

Livezeanu, Cultural Politics in Greater Romania: Regionalism, Nation Building,

and Ethnic Struggle, 1918- 1930 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995)

and Radu Ioanid, The Holocaust in Romania: The Destruction ofjews and Gypsies

under the Antonescu Regime, 1940- 1944, translated from the French by Marc

J. Masurovsky (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee in association with the United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2000).

23

JERZY GROTOWSKI'S BRIGHT ALLEY

Magdalena Hasiuk

Relations between space and the events which take place therein,

like the memory of place, are problems often discussed in diverse contexts.

And yet the interrelations between space and action, and by extension,

between space and time, continue to be among the most mysterious.

It is no coincidence that the first phase of the three-year long

project 'Jerzy Grotowski: the Past and the Present of the Research," entitled

"The Laboratory Theatre: Opole-Wrodaw 1959-1969," was held in the

hangars of an old factory transformed into a museum: the Museo Piaggio in

Pontedera. The space where craftsmanship and history met theatre ideally

conveyed the most important aspects of the work of the Laboratory

Theatre.

1

It was no coincidence either that most of the project's second phase

devoted to the Paratheatrical Activities and the Theatre of Sources

2

was held

in Poland at Brzezinka near Oldnica. Here at beginning of the 70s

Grotowski turned an old farmhouse and outbuildings surrounded by the

forest into the headquarters for his subsequent work on a number of

projects. No wonder that the discussions of the Paratheatrical Activities in

the space where they came into being acquired additional significance. All

the more so in that the memory of the place connected to the activities of

Grotowski's company was superimposed on an earlier memory-the old

sheepfold transformed into an exercise studio. The stone farmhouse lighted

only by a few small windows brings to mind the cave in Plato's Republic.

Engel nicht, Menschen nicht,/ und die findigen Tiere marken es schon,l dass

wir nicht sehr verlasslich zu Haus sind/in der gedeuteten Welt. 3 (Neither men nor

angels,/ and the clever animals have already marked/ that we are not very

securely at home/ in our conceptualized world.) Entering the farmhouse for

the first time, I recalled these lines from Rilke's Duino Elegy. A moment later

I reflected on the archetype of the animal and the deep layers of the human

unconscious. L'animal, qui est dans l'homme sa psyche instinctuelle, peut devenir

dangereux ( . .) L'acceptation de l'dme animate est Ia condition de !'unification de

l'individu, et de la plintitude de son ipanouissement. 4 During these cool Polish

autumn days, a blazing fire and music by the Milan Mela ensemble became

24

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

intertwined with recollections of activities going beyond art, whose aim was

to make contact at one of the deepest and most human of levels.

The conference "Jerzy Grotowski-the Past and the Present of the

Research: The Paratheatrical Activities 1969-1978. The Theatre of Sources

1976-1982" opened in Wroclaw with a retrospective screening of archival

films about Grotowski's activities and those of his co-workers during the 70s.

For the most part these consisted of filmed transcripts of conversations,

sessions and workshops. Nienad6wka, a very personal film made by

Mercedes Gregory in 1980 tracing the return of the already famous

Grotowski to the village of his childhood, clearly stood out. For us, the

participants at the conference, it was a journey to the beginnings.

Next morning, after the ceremony at which one of the streets in the

Wrodaw Market Place was renamed Jerzy Grotowski Alley, we left for

Brzezinka. It is worth mentioning that those who participated in the

paratheatrical activities must have followed that route many times. Now

we, the conference-goers, were covering the same ground. After our arrival

in Brzezinka, in her opening remarks Carla Pollastrelli, the co-initiator and

co-organizerS of the conference, outlined its origins and aims: "We did not

want it to be just another scholarly conference. Our aim was to build a

bridge for the new generation of theatre artists and scholars who could not

witness or participate in Grotowski's creative pursuits." She pointed out the

elements of continuity and rupture in the practice and creative thought of

the Laboratory Theatre. She stressed the fact that from the perspective of

time the most dramatic instance of rupture- as the paratheatrical activities

were considered- is now regarded as a stage in the total continuity and a

natural consequence of the earlier work. Pollastrelli also talked about the

difficulties connected with any proper assessment of that long and rich

period consisting of various projects in many different versions. This subject

was later taken up by Zbigniew Osinski. Pollastrelli also mentioned "the

present-day research" and ongoing work in Pontedera conducted by the

group under Thomas Richards's guidance. Another problem discussed from

the beginning of the session was the exact starting date of the para theatrical

activities. Ludwik Flaszen placed it in December 1970, considering the

lectures that Grotowski gave in the United States at that time as the

manifestoes of the new research.

The first meeting, in which Rena Mirecka, Ludwik Flaszen and

Zygmunt Molik took part, was moderated by Zbigniew Osinski. He

mentioned other people who had been invited to the conference but who

25

for various reasons were unable to come to Brzezinka. Osinski said that the

seminal idea for the conference came with the publication of The Grotowski

Sourcebook. 6 He pointed out the differences between the English and Polish

versions of the basic theoretical texts on the paratheatrical activities: Holiday

and The Theatre qf Sources (first published in Polish in the 70s), and the

identically titled texts in The Grotowski Sourcebook.? "The self-interpretation

of the texts made by Grotowski, who by montage-like editing completely

altered their meaning, is the most fascinating challenge for the researcher,"

Osinski commented. He also said that a book prepared by the organizers of

the conference containing texts by Grotowski and Flaszen as well as

interviews with Ryszard Cidlak, Jacek Zmyslowski, Zbigniew Cynkutis,

Stanislaw Scierski (originally published by the Polish magazines Odra and

Dialog), could not be published because Grotowski's heirs voiced objections

and would not grant permission. Focusing on the basic problem of the

seminar, Osinski posed the question: "To what extent did Grotowski

minimize the influence that his activities in the 70s had on his subsequent

work? Would the achievements in California and Pontedera have been

possible without the paratheatrical activities and the Theatre of Sources?

How can the language of experience be translated into a discursive one?"

In his long and passionate presentation, Ludwik Flaszen argued that

the 70s had been the happiest period in Grotowski's personal life and in that

of many of his co-workers. In trying to establish the origin of the

paratheatrical activities, Flaszen singled out his production of Mickiewicz's

Forifathers' Eve and his attempt to recreate a mystery drama, and he stressed

the influence of Grotowski's life-long religious sensibility. In his own texts

from the early 60s, Flaszen found the call for "a suicidal plunge into sources"

and the desire "to immerse theatre in life." (Apparently his text from the

paratheatrical period devoted to "Meditations on the Voice" was an

accurate prediction of activities developed in Pontedera many years later.)8

Flaszen also stressed how decisive an influence Grotowski's work with

Cidlak had had on the development of the paratheatrical activities,

especially as their relationship changed from director to actor to person to

person. In Flaszen's opinion, the activities in the 70s were also inspired by

the critique of the culture of the West (with its mass culture, its insincerity

different from that in totalitarian societies, its rationalism, its traditional

body-soul dichotomy, and its pragmatic thinking) that Grotowski and

Flaszen jointly undertook at that time. They lamented that Western man

did not know how to live "hie et nunc" in "the eternal present," free from

26

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

the demons of the past and the future. Flaszen also talked about

Grotowski's literal treatment of words which others at the time considered

metaphors; about brotherhood with all creation, about the idea of a

humanity free from original sin and living in a primal state of innocence,

which Grotowski especially longed for. The paratheatrical activities seemed

to Flaszen to be a transition from individual technique to collective

technique. It was work in a group, which was at the same time an isolated

activity. Flaszen mentioned the disappointments that occurred in

Brzezinka, emphasizing Grotowski's talent for turning all his crises into

victories. Flaszen pointed out that the paratheatrical activities were born out

of feelings of helplessness and defeat during work on Apocalypsis cum Figuris.

Another change for Grotowski in the 70s was his total abandonment of any

sort of teaching; as Flaszen explained, "he quit as a teacher of the

performer." "Likewise he left the theatre only to return to it in the end. For

as we say in Cracow, nothing doing without theatre," Flaszen concluded

half-jokingly. Trying to answer Osinski's question as to why Grotowski

minimized the influence of the paratheatrical activities and the Theatre of

Sources on his subsequent work, Flaszen explained that the fundamental

ideas for the activities developed in the 70s (i.e., resacralization of the body

and of nature, ecology of man, unorthodox religiosity, interactivity,

reciprocal activity) have since then been regarded as commonplace and

banal. "Grotowski was fleeing from any form of popularity and fashion. He

was deeply embarrassed by his own naivete in that period," Flaszen added.

He concluded his presentation by asking, "What is left of the paratheatrical

activities?" The answer came immediately: "Outstanding men of the

theatre-Wlodzimierz Staniewski, Tomasz Rodowicz and Mariusz Golaj,

and also that small spark in many people the world over which is their

sustenance and helps them live through difficult moments."

In a narrative full ofbeautiful images, the actress Rena Mirecka recalled

her personal experiences and her spiritual journey. The same themes were

touched upon in The Way, a film made by Mirecka in conjunction with

Mariusz Socha and Ewa Benesz, which was shown in the evening. The Way

is the record of a deeply personal and unusual ritual in which theatre gives

way to an unfettered expression of spirituality. She began her presentation

by remembering Grotowski as a cruel but splendid teacher and by recalling

many co-workers who are no longer alive. She talked about her spiritual

meeting in the meadow in Brzezinka, and also about meetings that could be

experienced by body and soul, heart and mind. She told about her trips to

27

India and the work she did in Sardinia, and about her search for inner

harmony and freedom. She identified love as the fundamental value that

ordered her pursuits and her life.

Later on other speakers, especially Jairo Cuesta and James Slowiak,

recalled how Grotowski taught love of work. Zygmunt Molik, in a friendly

conversation with Ludwik Flaszen, focused attention on how the acting in

Apoca{ypsis cum Figuris changed after experiences in Brzezinka. "The

structure of the production was blown up from within by what we brought

back from that forest, those meadows, and those surroundings. Brzezinka

was mystery and magic creating a feeling of harmony. That's where I

understood that achieving impossible is possible," Molik summed up.

The afternoon session, "The Testimonies of the Leaders," was

opened by Jairo Cuesta and Maud Robart. As an introduction, Grzegorz

Ziolkowski talked about Gildia, a project that Cuesta and Slowiak have been

working on for the past two years in Olsztyn. "My first challenge working

in the Theatre of Sources was to let the original material come into being.

To stand still and be at the source," Cuesta explained. "Realize where you

come from. That is the essence of wisdom," he said, referring to Lao Tse's

Tao Te King, for only then "will nature, as it was the case for us in Brzezinka,

become a door opening to something more." Cuesta talked about attention,

preparedness, confidence and awareness; about connection with life based

on a close relation to everything around us, and about the great daring of

being faithful to oneself. Repeatedly he quoted from Grotowski's text,

"Action is Literal,"9 in which the creator of the Theatre of Sources

recommended looking for answers to the most important questions not in

words but in actions. Cuesta singled out movement/stillness and song as the

basic elements of the work in Brzezinka. Creativity is the link between one's

origin and one's work. Q!Ioting Grotowski, Cuesta said that it is only

through work that we can stand up to the challenges of life. Speaking about

the principles of work in the Theatre of Sources, Cuesta referred to Ortega

y Gasset's prose and the awareness of paradox present in Morris Berman's

wntmgs. "For Berman paradox is a very old memory-a genetic

remembrance. In human beings such an awareness is based on the

simultaneous appearance of extreme emotions and the preservation of the

sort of conflict from which a new kind of reality can emerge," Cuesta said in

summation. Twenty years after his experiences with the Theatre of Sources,

what remains the most important value for Jairo Cuesta is his work. "Happy

is he who is at the beginning," Cuesta added.

28

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

Maud Robart declared that she feels no need to talk about her work

with Grotowski or about the Saint-Solei! group. She said that if she were

asked to repeat her experience with the Theatre of Sources now, her answer

would be "no." She explained that this is not a criticism of the Theatre of

Sources, but only of her participation in it. "In terms of technique in the

Theatre of Sources there was nothing that could be explored, for what could

be accomplished in a few days with ever-changing groups of people?" she

asked. Robart, however, agreed to take questions from the audience. With

great precision she talked about her work with young people, in which she

introduces elements of Haitian voodoo (tempo-rhythm). "For me, even

today, voodoo represents a certain fundamental value that all traditional

techniques are based on. That value is its relation to life. Voodoo says: let's

affirm life. Life in this dimension is always holy." Discussion arose on

specific problems which in Robart's opinion can be solved only through

action, not through words. She emphasized the value of effort and grace in

one's work.

Vlado Sav, who took part in Robart's workshop in the 70s, recalled

her great respect for creativity of others, even if it turned out to be of

negligible quality. He said that there are people who devote their entire

lives to fathoming certain things, and there are people-and they are in the

majority- who can commit themselves only for a short term. "Grotowski

also was concerned with questions of verticality and horizontality.

Although I'm concerned with the roots, I still feel great respect for people

who move on the surface," Sav concluded.

A screening of the unique film Vigils made by Mercedes Gregory in

Milan during the workshops conducted by Zmyslowski closed the day's

proceedings.

The next day at Brzezinka the seminar was opened by Renata

Molinari who read excerpts from her diary completed a year after her

participation in the Theatre of Sources. The diary, written in a simple,

beautiful style, is yet another attempt at transferring a direct experience into

words. Molinari's writing consists of a series of impressions based on her

observations and her emotions as a young woman, with a description of the

particular exercises and tasks that Grotowski imposed on the international

group of participants in the project. She wrote about her opening to new

possibilities of perceptions, about silence, about li stening, about

imagination and solitude; about self-irony which is an invaluable aid in work

and allows one to go beyond the threshold of one's abilities; about the

29

encounter with oneself that occurs at the moment when all that has been

learned is forgotten. In her experience, as well as in that of] ana Pilatova, the

key element of the work was waiting. Pilatova recalled her initiation into the

Laboratory Theatre workshops in the late 60s: "I had to wait one week.

During that week I understood that the ability to work is an unimaginable

privilege." Molinari added: "While you are waiting, the most important

things are taking place-you are learning exactly why you are there. Waiting

is a kind of action in which time is the acting element."

The next conversation, with Lech Raczak, founder of the Theatre of

the Eighth Day, opened with Ludwik Flaszen's remark that forcing someone

to wait is a form of domination (earlier Flaszen likened Grotowski to Ivan

the Terrible). Thanking the organizers for the invitation to participate,

Raczak turned to his critical text, Para-ra-ra.

1

0 He explained the motives that

led to its writing. It was not in the least an attack on the Laboratory Theatre,

but was rather an attempt to make a dent in the trend, then prevalent in

Poland, toward a "peaceful" paratheatricality, while the country was deeply

engaged in a bitter political battle. Raczak admitted that his polemic grew

out of conversations he had had with participants in the meetings and that

he himself had never participated in the Laboratory Theatre workshops. In

the course of the session this statement met with sharp criticism from Marek

Musial. Raczak also recalled the help that Grotowski had given the Theatre

of the Eighth Day during its emigre days in the 80s.

The second part of "Testimonies of the Leaders" began with a

presentation by Abani Biswas of dance-theatre activities based on traditional

Hindu forms of theatrical performances and battle techniques. Biwas talked

about his meeting with Grotowski, their joint work on voice in India and

their work on silence in Brzezinka. In his beautiful narrative about his

search for inner harmony Biwas drew upon Hindu philosophy. He

acknowledged that experience of the existence of Purusha (silence) and

acceptance of human suffering are the basic principles of his work.

In characterizing the work in Brzezinka, Marek Musial used terms

already introduced by the previous speakers: waiting, silence, attention,

renunciation of passivity, and he also noted that any activity is necessarily

aimless and any search is a solitary pursuit that cannot be directly

transmitted. He admitted that participation in the paratheatrical workshops

signaled a new perspective and inspired the participants to do in life what no

one had ever done before (and probably would never do again-as Katharina

Seyferth was to observe). The everyday repetitious routine regardless of

30

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

circumstances, the particular experience of being present "here and now "

was transformed into an extraordinary person-to-person relationship. "I

haven't come back to Brzezinka for twenty years because this place is too

strongly connected to what had been happening here."

Katharina Seyferth took up themes introduced by Marek Musial

and Renata Molinari. She discussed the very intense and solitary work that

the participants in the workshops totally committed themselves to, and

talked about learning through action and the search for movement that

would include rest. She also pointed out that another place of work-

Ostrowina-had had an influence on the paratheatrical activities. In

Ostrowina, which is less isolated from the outside world than Brzezinka, the

participants learned source techniques, personal courage, and awareness.

"What took place in Brzezinka would not have been possible without

Ostrowina," Seyferth concluded. She also made reference to Vigils, realized

jointly with Jacek Zmyslowski, which resulted in a particular unity in the

activity, a change of awareness and heightened stamina, and even a

transformation of the place itself Seyferth expressed her gratitude for the

possibility of undertaking such work and for the human warmth that

accompanied it. "Grotowski's presence made many things possible."

If the evening screening of Louis Malle's film My Dinner with Andre

had divided the conference participants, all was forgotten by the time the

concert, Songs of the Bauls by the Milon Mela ensemble, was over.

The recapitulation of the conference, which took place on Sunday

at the Grotowski Center in Wrodaw, offered a veritable kaleidoscope of

thoughts, positions, and expectations. It started with Osinski's observation

that each person has his or her own paratheatrical activities and Theatre of

Sources resulting from the differences among human beings. He also

pointed out how difficult it is to return to reality after any exceptional

experience. Grzegorz Ziolkowski commented on how enduring the memory

of the paratheatrical activities has turned out to be and, referring to the

renaming of a street in Grotowski's honor, he proposed calling the

conference "a bright alley"

11

as opposed to "a dark alley or blind alley"

(which has a strong negative meaning in Polish). He also mentioned

Gurdijeffs name for the first time during the entire conference, an obvious

connection that has been neglected in interpreting the paratheatrical

activities.

Flaszen talked about the value of silence which he had learned

during the paratheatrical activities, and he referred to the new animism and

31

the esoteric roots of all science and art. A longer commentary came from

Robart who read a letter from Marianne Ahrne describing the work that she

had done with the Tahitians on ritual dances at Brzezinka. Rafal Fabicki,

who was active in the Polish political underground of the early 80s, talked

about the subtle connections between paratheatrical activities and political

activities. Jairo Cuesta emphasized the broad perspective and numerous and

varied sources that have to be taken into account in any attempt to analyze

Grotowski 's work. He cautioned against a too facile adaptation of

Grotowski's views to the measure of one's own perceptions. James Slowiak

concluded the kaleidoscopic session by addressing the young people in the

audience and urging them to enlarge the sphere of freedom through culture

and to find their own creative response to the problems of the world they

live in. The conference ended in a fascinating discussion between Vlado Sav

and Leszek Kolankiewicz who proposed to regard the paratheatrical

activities as present-day Eleusinian mysteries. Both agreed that such an

interpretation is a valid one, but differed as to the significance of certain

details in the mysteries. In that fashion we returned to the beginnings.

For Grotowski, as someone for whom nothing was ever finished,

everything existed in a state of process. The conference, in which, as in the

paratheatrical activities, dozens of threads, thoughts, and positions would

appear and become interwoven into ever new versions and interpretations,

was undoubtedly a great success. After many difficult years, Brzezinka, an

important place, has come back to life. Let us hope it will be totally reborn.

A journey to the sources takes us through many places, landscapes,

and people, through many twists and turns of individual experience,

solitude, and suffering, through the Mystery. Like the journey to the East,

the journey to the sources never ends.

NOTES

All statements by conference participants are quoted from my notes, which

were not authorized.

1 See Janusz Degler, "In Pontedera After Grotowski and About Grotowski,"

in Slavic and East European Peiformance, Vol. 22, No.1 (Winter 2002), 32-39.

2

The conference, "Jerzy Grotowski: The Past and The Future of the

Research: The Paratheatrical Activities 1969-1978. The Theatre of Sources

32

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

1976-1982," was held in Wrodaw and Brzezinka, September 26-29, 2002.

3 Rainer Maria Rilke, Duinesian Elegies. The First Elegy. German Text with

English Translation and Commentary by Elaine E. Boney, (Chapel Hill:

The University of Carolina Press, 1975), 3.

4 Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionnaire des Symboles, (Paris:

Robert Laffont!Jupiter, 1992), 46.

5 The second part of the project was organized by the Center of Studies on

Jerzy Grotowski's Work and the Cultural and Theatrical Research in

Wrodaw, the city of Wrodaw, and the Fondazione Pontedera Teatro. The

organizers of the Wroclaw Conference were jointly Zbigniew Osinski and

Jaroslaw Fret (The Grotowski Center) and Grzegorz Ziolkowski (the Adam

Mickiewicz University in Poznan).

6 Lisa Wolford and Richard Schechner, eds. The Grotowski Sourcebook,

(London: Routledge, 1997), 213-23.

7 Texts first published in Polish: Jerzy Grotowski, Odra, No. 6,

1972, 47-51; Jerzy Grotowski, "Teatr Zrodel," Zeszyty Literackie, Vol. 5, No.

19, 1987, 102-15; Jerzy Grotowski, "To stanie mozliwe.

Wypowiedi w Royaumont, 11 paidziernika 1972," Kultura, No. 52, 1972.

English translation: Jerzy Grotowski, "Holiday," The Drama Review, Vol. 17,

No. 2, 1973 (T-58), 113-19. See also: Jerzy Grotowski, "Holiday: The day is

holy," in Lisa Wolford and Richard Schechner, eds., The Grotowski

Sourcebook (London: Routledge, 1997), 213-23. Also J erzy Grotowski,

Theatre of Sources, ibid, 250-68.

8 "The human voice, the action of the voice, is the vehicle by which we

reach the dormant and forgotten energies in man, the source experiences, a

different perception." See Ludwik Flaszen, "About the art of dialogue and

other matters," Odra, No. 4, 2000, 49. See also Ludwik Flaszen,

"Conversation," in M. Miller, Reporter6w spos6b na iycie, (Warsaw: Czytelnik,

1983), 309.

9 Jerzy Grotowski, "Dzialanie jest doslowne," Dialog, No. 9, 1979, 95-101.

10 Lech Raczak, "Para-ra-ra," Dialog, No.7, 1980, 132-7.

11 I have used Ziolkowski's formulation as the title of my essay.

Translated by jadwiga Kosicka

33

NORD-OST: TRAGIC NIGHTS IN THE THEATRE

Maria Ignatieva

On December 20, 2002, Georgii Vassiliev, director and co-producer

of Nord-Ost, announced that the musical would reopen and tickets went on

sale. By late January 2003, the Palace had been renovated and new blue seats

were installed instead of the old red ones. The renovation cost the city of

Moscow two and a half million dollars; other sponsors contributed

financially to the restoration as well. Two red armchairs were left in place

as a tragic reminder of the hostage-taking and siege. In these red chairs, a

young couple, a husband and wife from a Moscow suburb, lost their lives,

hand-in-hand, not separated by death.

A total of seventeen people involved in the musical died: nine

musicians, four auditorium attendants, a music supervisor, the souvenir

seller, and two young actors, Kristina Kurbatova, fourteen years old, and

Arsenii Kurilenko, thirteen, who played the leading characters as youngsters.

A group of former hostages expressed their willingness to attend

the re-opening of the musical. Most of the actors, including the surviving

child actors, agreed to take up their roles again in the new version. Tickets

for the first performance (on February 10, 2003) sold out. However,

demographically the audience had changed: there were fewer women, more

men and many young people in their late teens, who, as we know, are

fearless.

Life in Moscow goes on; though many people I talked with do not

believe that the Nord-Ost terrorist episode will be the last. In December 2002,

anonymous callers warned three times that bombs were planted in the

theatre where 42nd Street was playing, and the spectators were hastily

evacuated. Were these real terrorist threats? Merely hooligans' jokes? The

competitors' revenge?

There are a number of issues related to Nord-Ost and the tragic

events following the terrorists' seizure of the theatre that are worth looking

at more closely: the book on which the musical was based, the mounting of

the production, and the role it played in Russian cultural life.

Nord-Ost is based on a novel, The Two Captains, written by

Veniamin Aleksandrovich Kaverin-real family name Zilber--(1902-1989) in

34

Slavic and East European Peiformance Vol. 23, No. 1

1946. The book has been a bestseller since the late forties; it combines a

realistic style of pristine linguistic simplicity with strong romantic

undercurrents. The novel takes place primarily in Moscow and Leningrad

between 1915 and 1945. In the novel's expository opening, we learn that

Captain Ivan T atarinov has disappeared in the North Sea during the first

decade of the twentieth century. Twenty years later, a young man, the

orphan Sanya Grigoriev, decides to look for the Captain and restore his

good name. Befriended by the Tatarinovs, in love with the Captain's

daughter Katya, Sanya discovers that the Captain was sent to his death by

his cousin, a well-known professor. As a result of his investigation, Sanya is

libeled and thrown out of the Tatarinov's house. Struggling alone and

without support, he becomes a pilot. But misfortune follows him: he has

powerful enemies. A fearless pilot, he fights the Nazis during World War II

in 1941 and is almost killed. At the end of the War, Sanya spends months

in a desperate search for Katya, of whom he has lost track after her

evacuation from Leningrad. The novel ends as Sanya discovers Captain

Tatarinov's remains, proving the guilt of his enemies, and is reunited with

Katya, the love of his life.

One ofKaverin's favorite themes is the false accusation of innocent

victims. Unable to write directly in the 1930s and 40s about the labor camps

and the so-called "enemies of the people," Kaverin, by historical analogy,

put on stage the central issue of the time. His main characters, libeled and

outcast, struggle all their lives to prove their innocence and to have justice

re-established. Kaverin's books are about the power of malevolence to crush

individuals. One of the reasons for the Russian infatuation with The Two

Captains is that Kaverin gave a whole generation victimized by history a

hope of seeing justice done. The government in The Two Captains, which

served as a tool of evil in the wrong people's hands, finally helps Sanya and

Katya to reveal the truth.

Veniamin Kaverin was one of a very few writers who stoically

maintained independence in the Soviet Writers' Union. This independence

was dramatically displayed by his being the only member to vote against the

Boris Pasternak's expulsion from the Union. It is highly ironic that his book,

The Two Captains, seemed to conform to the ideals of Socialist realism, and

that it received the Stalin's Prize for Literature in 1946. There is a further

tragic irony in the fact that Nord-Ost, which had sought to restore the

romantic ideals of earlier twentieth-century Russian history, was taken by the

Chechens, through their occupation of the theatre, as a symbol of the

35

present government's injustice and oppression.

It is not surprising that The Two Captains was chosen as the book for

the first large-scale Russian musical. The story is known and loved by the

public. It was filmed twice in the Soviet Union. Its underlying romantic

assumptions provide a wealth of lyrical themes for songs, while its fully

dimensional characters are heroes with whom Russians can identify.

In the late 1950s, two boys fell in love with the novel and played

The Two Captains as a childhood game, just as I and other children I knew

had. The boys' names were Georgii Vassiliev and Alexei Ivashchenko.

lvashchenko became a professional actor; he remained loyal to his friend

Vassiliev, who majored in both geology and economics and earned a Ph.D.

in economics. Vassiliev worked in the Major's office and became President

of the Moscow Stock Market and owner of a telephone company. Now in

their late forties, lvashchenko and Vassiliev played guitar duets in their spare

time and went mountain-climbing together.

The two friends, whose love for The Two Captains never abated,

decided in 2000 to bring it to the stage, and to make it as close to their

dreams as possible. Once they made up their minds, Vassiliev and

lvashchenko flew to the North Pole to see where the real Sanya might have

landed his airplane. A real 1940 airplane would be one of the props.

Without any professional experience in producing musicals, they assembled

an excellent team and created a "Broadway" show in the "proletarian"

district of Moscow. Nord-Ost opened on October 19, 2001, proving once

again that fine achievements in Russian theatre could be brought by

amateurs, who, not knowing that some things simply could not be done,

simply did it. Nord-Ost became a hit overnight. An English-language version

was created, and the musical was ready to tour the world as soon as they

could find sponsors and invitations.

There was something else even more important. This was an

attempt to create a Russian national musical, based on a story loved by

millions, that had heroic dimensions. During the last fifteen years, the

Russian people had seen so many heroic deeds and myths from the past

debunked and turned upside down. The Two Captains survived the test of

time. The musical presented the heroism of individuals, not of the

discredited Soviet system. The people were badly in need of heroic

individualism. In such nostalgia lay the appeal of Nord-Ost.

The tragedy of Nord-Ost has involved many aspects of theatre. Here

in Russia, where theatre is a deep passion, the terrorist act was staged

36

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

theatrically. Some spectators, who came to see a heroic musical, died heroic

deaths. The terrorists took center stage and played their war out in the

theatre. Georgii Vassiliev himself became Captain under the circumstances:

he tried to negotiate with the terrorists and talked to the hostages all the

time. As Vassiliev said in an interview on Russian Television, the terrorists

wanted to see themselves invading the theatre, as it was taped on the security

cameras. The terrorists demanded that Vassiliev show them the tape on

October 26. He was forced to comply. The showing took place just before

the gas was vented, so that some of the terrorists were killed while they were

watching themselves entering the stage of Nord-Ost.

For people throughout the world, Nord-Ost will remain a symbol of

theatre and life merged in a tragic embrace. As 9-11 had done for Americans,

so Nord-Ost marked for Russians the beginning of a new era. In the Nord-Ost

hostage crisis, terrorism struck at the core of the Russian national character,

revealing that there was no place to hide. There is no safe oasis anywhere in

the world any longer, not even in culture, theatre, and literature, where the

Russians have traditionally escaped from social problems. The re-opening of

the musical was a declaration that the spirit of the cast, crew and spectators

has not been broken. There will be no surrender to terrorism: our triumph

over the terrorists lies in the determination to keep going and to live.

37

SLOBODAN SNAJDER: PLAYWRIGHT!

Milos Lazin

At the age of twenty, he became one of the creators of the journal

Prolog, which would influence the theatrical scene of the former Yugoslavia

for two decades. At twenty-one, he had his first play produced by the

Repertory Theatre of the City of Zagreb. At twenty-nine, he founded a

publishing house, whose output of about fifty titles2 would revolutionize the

way people thought about theatre in his country. At thirty, he became a

"star author" of such magnitude that the theatres of the ex-Federation would

fight to produce his plays.

This "irresistible rise" has undoubtedly been possible because

Slobodan Snajder3, taking an alternate route, did not follow the traditional

course of the other film and theatre writers from Communist countries: he

never took a course in dramaturgy.

But his exceptional career does not stop there. Coming from a

country whose theatre was unknown abroad, he was 44 when his Croatian

Faust entered the repertory of the Vienna Burgtheater. In the next few years,

Snajder's various plays appeared on German stages in Mulheim,

Frankfurt/Oder, Frankfurt/ Main, Tubingen and Bochum, by famous

directors such as Roberto Ciulli, Hans Hollmann, and Werner Schroeter. In

the late 1990s, he became internationally known with Snakeskin. The piece

was first produced in several German theatres, and then in European

capitals, Oslo, Rome, Vienna, Dublin, Warsaw, Cracow, Copenhagen, and

finally in Belgrade in 2001.4

The student turbulence of 1968 was Slobodan's real "education

period." He left his native Zagreb to join the student movement in

Belgrade, which happened two months after the revolution in Paris, a

negligible delay in the history of the Balkans vis-a-vis that of the West.

Nevertheless, this "Belgrade Spring" was in Western media eclipsed by the

Prague Spring. What happened in Belgrade? The anti-Fascists who

supported Tito in the revolution (1941-45) were accused by their children of

having betrayed their own ideals of freedom and equality. The new

generation wanted their own "revolution." But this "children's revolution,"

which, after one month of university sit-ins, was reduced to silence by the

38

Slavic and East European Performance Vol. 23, No. 1

Slobodan Snajder

39

40

Snakeskin at the Royal Danish Theatre,

Copenhagen Denmark, 1998