Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effects of Family History and Place and Season of Birth On The Risk of Schizophrenia

Uploaded by

Anastasia FebriantiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effects of Family History and Place and Season of Birth On The Risk of Schizophrenia

Uploaded by

Anastasia FebriantiCopyright:

Available Formats

Vol ume 340 Number 8

603

EFFECTS OF FAMI LY HI STORY AND PLACE AND SEASON OF BI RTH ON THE RI SK OF SCHI ZOPHRENI A

EFFECTS OF FAMILY HISTORY AND PLACE AND SEASON OF BIRTH

ON THE RISK OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

P

REBEN

B

O

M

ORTENSEN

, D.M.S

C

., C

ARSTEN

B

CKER

P

EDERSEN

, M.S

C

., T

INE

W

ESTERGAARD

, M.D.,

J

AN

W

OHLFAHRT

, M.S

C

., H

ENRIK

E

WALD

, D.M.S

C

., O

LE

M

ORS

, P

H

.D., P

ER

K

RAGH

A

NDERSEN

, D.M.S

C

.,

AND

M

ADS

M

ELBYE

, D.M.S

C

.

A

BSTRACT

Background

Although a family history of schizo-

phrenia is the best-established risk factor for schizo-

phrenia, environmental factors such as the place and

season of birth may also be important.

Methods

Using data from the Civil Registration

System in Denmark, we established a population-

based cohort of 1.75 million persons whose mothers

were Danish women born between 1935 and 1978.

We linked this cohort to the Danish Psychiatric Cen-

tral Register and identified 2669 cases of schizophre-

nia among cohort members and additional cases

among their parents.

Results

The respective relative risks of schizo-

phrenia for persons with a mother, father, or sibling

who had schizophrenia were 9.31 (95 percent confi-

dence interval, 7.24 to 11.96), 7.20 (95 percent confi-

dence interval, 5.10 to 10.16), and 6.99 (95 percent

confidence interval, 5.38 to 9.09), as compared with

persons with no affected parents or siblings. The risk

of schizophrenia was associated with the degree of

urbanization of the place of birth (relative risk for the

capital vs. rural areas, 2.40; 95 percent confidence in-

terval, 2.13 to 2.70). The risk was also significantly

associated with the season of birth; it was highest

for births in February and March and lowest for

births in August and September. The population at-

tributable risk was 5.5 percent for a history of schizo-

phrenia in a parent or sibling, 34.6 percent for urban

place of birth, and 10.5 percent for the season of

birth.

Conclusions

Although a history of schizophrenia

in a parent or sibling is associated with the highest

relative risk of having the disease, the place and sea-

son of birth account for many more cases on a pop-

ulation basis. (N Engl J Med 1999;340:603-8.)

1999, Massachusetts Medical Society.

From the Department of Psychiatric Demography, Institute for Basic

Psychiatric Research, Psychiatric Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, Ris-

skov (P.B.M., H.E., O.M.), and the Department of Epidemiology Re-

search, Danish Epidemiology Science Center, Statens Serum Institut,

Copenhagen (C.B.P., T.W., J.W., P.K.A., M.M.) both in Denmark. Ad-

dress reprint requests to Dr. Mortensen at the Department of Psychiatric

Demography, Institute for Basic Psychiatric Research, Psychiatric Hospital,

Aarhus University Hospital, Skovagervej 2, 8240 Risskov, Denmark, or at

ph.ph1.pbm@aaa.dk.

WIN and adoption studies strongly sug-

gest that genetic transmission accounts for

most of the familial aggregation of schizo-

phrenia.

1,2

However, little is known about

the contribution of familial aggregation to the oc-

currence of schizophrenia in the general population

and the mode of inheritance of the disease. Environ-

mental risk factors have also been suggested, includ-

ing maternal obstetrical complications,

3,4

influenza

infection during the mothers pregnancy,

5

season of

T

birth,

6

urban place of birth or upbringing,

7

and low

social class.

8

Questions about the relative importance of genet-

ic and environmental risk factors for mental disor-

ders, as well as their possible interaction, remain to

be answered.

9

Such questions would ideally be ad-

dressed by large studies of incident cases of schizo-

phrenia in representative samples of the general pop-

ulation. Population-based studies of family history as

a risk factor for schizophrenia

10

have been based on

prevalence rather than incidence and have not eval-

uated or quantified the relative contributions of, or

interactions between, genetic and environmental risk

factors for schizophrenia.

We used Danish population-based registries to

study the effects of family history, nonfamilial risk

factors, and their interactions on the risk of schizo-

phrenia.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Danish Scientific Ethics Com-

mittees. All live-born children and new residents in Denmark are

assigned a unique personal identification number, and informa-

tion about them is recorded in the Civil Registration System.

11

Individual information is kept under the personal identification

number in all national registers, thus ensuring accurate linkage of

information between registers without the necessity to reveal a

persons identity. We used data from the Danish Civil Registra-

tion System to obtain a large and representative set of data on

children born to Danish women. As described in detail else-

where,

12

we identified all women born in Denmark between April

1, 1935, and March 31, 1978, and all their offspring (2,043,492

people) who were alive on April 1, 1968, or who were born be-

tween that date and December 31, 1993. The identity of the fa-

ther was available for 1,996,726 (97.7 percent) of the offspring.

The offspring constituted the study population. A person could

be included both as an offspring and as a mother or a father.

The study population (mothers, fathers, and offspring) were

then linked with the Danish Psychiatric Central Register. The

Danish Psychiatric Central Register has been computerized since

April 1, 1969.

13

It contains data on all admissions to Danish psy-

chiatric inpatient facilities and at present includes data on approx-

imately 340,000 persons and 1.4 million admissions. There are no

private facilities for inpatient psychiatric treatment in Denmark.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

604

Febr uar y 25, 1999

The New Engl and Jour nal of Medi ci ne

The diagnostic system used during the study period was the

In-

ternational Classification of Diseases, 8th Revision

(ICD-8),

14

and

the diagnosis of interest was schizophrenia (ICD-8 code 295). In

ICD-8 schizophrenia is defined by prototypic descriptions of

symptoms, such as bizarre delusions, delusions of control, abnor-

mal affect, autism, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking,

15

whereas in the third edition, revised, and fourth edition of the

Di-

agnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-III-R

and DSM-IV, respectively) and the

International Classification of

Diseases, 10th Revision

(ICD-10), most of the same symptoms have

been transformed into explicit criteria. However, in a Danish reg-

ister sample of 53 patients with schizophrenia as defined by

ICD-8, 48 patients (91 percent) also met the criteria for schizo-

phrenia as defined by DSM-III-R,

16

suggesting that the vast ma-

jority of persons whom we identified as having schizophrenia

would meet the DSM-III-R criteria for the disorder.

Overall, 1.75 million offspring were followed from their fifth

birthdays or April 1, 1970, whichever came later, until the date of

onset of schizophrenia, the date of death, the date of emigration,

or December 31, 1993, whichever came first. Offspring were re-

corded as having schizophrenia if they had been admitted to a

psychiatric hospital with a diagnosis of the disorder. The date of

onset was defined as the first day of the first admission leading to

a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Parents were recorded as having

schizophrenia if they had ever been admitted with this diagnosis.

The register was assumed to be almost 100 percent complete dur-

ing the study period.

13

The relative risk of schizophrenia among the offspring was esti-

mated by log-linear Poisson regression

17

with the SAS GENMOD

procedure.

18

All relative risks were adjusted for age, sex, inter-

actions between age and sex, calendar period when schizophrenia

was diagnosed (1970 to 1974, 1975 to 1979, 1980 to 1984, 1985

to 1989, or 1990 to 1993), and age of the mother and father at

the time of the childs birth. Age, calendar period of diagnosis,

and schizophrenia in a sibling were treated as time-dependent

variables, whereas schizophrenia in a parent was treated as a var-

iable that was independent of time. The place of birth was clas-

sified according to the degree of urbanization: capital, suburb of

the capital, provincial city with more than 100,000 inhabitants,

provincial town with more than 10,000 inhabitants, or rural area.

The effect of the month of birth was modeled as a sine func-

tion with a period of 12 months and with both the amplitude and

the time of the peak risk estimated. The variance of the time of

the peak risk and that of the amplitude were calculated by the del-

ta method.

19

The adjusted-score test

20

suggested that the final re-

gression model was not subject to overdispersion. P values were

based on two-tailed likelihood-ratio tests, and 95 percent confi-

dence limits were calculated by Walds test.

21

The population attributable risk is an estimate of the fraction

of the total number of cases of schizophrenia in the population

that would not have occurred if the effect of a specific risk factor

had been eliminated that is, if the risk could have been reduced

to that of the exposure category with the lowest risk. The estima-

tion was carried out as described by Bruzzi et al.,

22

on the basis

of adjusted relative risks and the distribution of exposure in the

cases. The population attributable risk for season of birth, a con-

tinuous variable, was estimated by using a categorical approach in

which the fitted sine function was used to estimate relative risks

for the 15th day of each month.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distribution of persons in whom

schizophrenia developed and the person-years of ex-

posure to risk in the study population, according to

risk factors. Schizophrenia was diagnosed in a total

of 1857 sons and 812 daughters during the nearly

25 million person-years of follow-up. Among these

patients, 79 had a mother with schizophrenia, 33 had

a father with schizophrenia, and 4 had two parents

with schizophrenia. Fifty-nine patients had at least

one sibling with schizophrenia at the time that they

received their own diagnosis of the disorder. Overall,

there were 52 sibships with 2 affected siblings, 2 sib-

ships with 3 affected siblings, and 1 sibship with 4 af-

fected siblings.

The relative risks associated with the risk factors

identified in our study are shown in Table 2. Schizo-

phrenia in a parent or sibling, here referred to as a

family history of schizophrenia, was associated with

the highest relative risk of having the disease. There

was a slight reduction in the estimated risk associat-

ed with any specific category of family history after

adjustment for a family history of schizophrenia (Ta-

ble 2, second adjustment). Further adjustment for

place and season of birth (the full model) resulted

in only a slight additional reduction in the associa-

tion between family history and schizophrenia (Ta-

ble 2). In the following discussion, we will refer only

to the results of the full model.

The risk of schizophrenia was increased by a his-

tory of schizophrenia in the mother (relative risk,

9.31; 95 percent confidence interval, 7.24 to 11.96),

the father (relative risk, 7.20; 95 percent confidence

T

ABLE

1.

D

ISTRIBUTION

OF

2669 C

ASES

OF

S

CHIZOPHRENIA

AND

24.9 M

ILLION

P

ERSON

-Y

EARS

AT

R

ISK

IN

A

P

OPULATION

-B

ASED

C

OHORT

OF

1.75 M

ILLION

P

EOPLE

.

V

ARIABLE

N

O

.

OF

C

ASES

P

ERSON

-Y

EARS

Age (yr)

514

1519

2024

2529

3034

35

35

635

1152

659

170

18

13,594,827

5,234,270

3,539,876

1,894,835

602,770

66,536

Sex

Male

Female

1857

812

12,831,518

12,101,597

Place of birth

Capital

Suburb of capital

Provincial city (>100,000 population)

Provincial town (>10,000 population)

Rural area

Greenland

Other countries

Unknown

860

233

350

737

400

11

74

4

4,256,525

2,251,541

3,284,950

9,047,311

5,665,501

47,586

342,050

37,651

Family history of schizophrenia

Parent

Father affected, mother affected

Father affected, mother not affected

Father not affected, mother affected

Father not affected, mother not affected

Father unknown, mother affected

Father unknown, mother not affected

4

33

64

2317

15

236

1,067

44,251

55,683

24,144,738

5,494

681,881

Sibling

One or more affected siblings

No affected siblings

59

2610

25,534

24,907,580

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

EFFECTS OF FAMI LY HI STORY AND PLACE AND SEASON OF BI RTH ON THE RI SK OF SCHI ZOPHRENI A

Vol ume 340 Number 8

605

interval, 5.10 to 10.16), or a sibling (relative risk,

6.99; 95 percent confidence interval, 5.38 to 9.09).

The risk associated with having a sibling with schizo-

phrenia was not affected by the sex of the sibling,

and the risk associated with having a parent with

schizophrenia was not significantly affected by which

parent had the disease. The relative risk was 46.90

(95 percent confidence interval, 17.56 to 125.26) if

both the father and the mother had been hospital-

ized with schizophrenia, and there was no statistical

interaction between the fathers status and the moth-

ers status with respect to the disorder. The risk of

schizophrenia for persons with unknown fathers and

no maternal history of schizophrenia was twice the

risk for persons with no parental history of the dis-

order (the reference group).

Among the other risk factors for schizophrenia,

the strongest was an urban place of birth. As com-

pared with persons born in rural areas, those born

in the capital (Copenhagen) had a relative risk of

2.40 (95 percent confidence interval, 2.13 to 2.70),

those born in provincial cities with more than

100,000 inhabitants or in suburbs of the capital had

relative risks of approximately 1.6, and those born in

towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants had a rel-

ative risk of 1.24 (95 percent confidence interval,

1.10 to 1.41). The risk of schizophrenia was also

increased for children born to Danish mothers in

countries other than Denmark (relative risk, 3.45;

95 percent confidence interval, 2.69 to 4.44) or in

Greenland (relative risk, 3.71; 95 percent confidence

interval, 2.04 to 6.76).

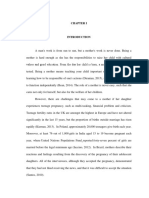

Figure 1 shows the effect of the month of birth

on the risk of schizophrenia. The amplitude of the

sine function was estimated to be 1.11 (Table 2),

which means that the maximal and minimal relative

risks associated with the month of birth were 1.11

and 1/1.11, respectively. The time of the peak risk

was estimated to be March 6, which means that chil-

dren born in early March had a risk that was 1.1 times

(95 percent confidence interval, 1.06 to 1.18) the

risk for those born in early June or early December.

There was no interaction between season of birth

and the other variables in the model. There was a

weak interaction (P=0.03) between the variables for

the presence or absence of a family history of schizo-

phrenia and those for place of birth. However, if an

urban place of birth is seen as involving exposure to

an unknown urban factor, there is no clear trend in

the interaction. Thus, it appears that family history

*The relative risk was adjusted initially for agesex interaction, calendar year of diagnosis, and ages of the father and mother (first adjust-

ment) and then for family history or, alternatively, other factors as well (second adjustment). The third adjustment (full model) was for all

the variables listed. CI denotes confidence interval.

This was the reference category.

For all three adjustments, the estimated peak of the sine function was at March 6 (95 percent confidence interval, February 6 to April 5).

T

ABLE

2.

A

DJUSTED

R

ELATIVE

R

ISK

OF

S

CHIZOPHRENIA

A

CCORDING

TO

F

AMILY

H

ISTORY

, P

LACE

OF

B

IRTH

,

AND

S

EASON

OF

B

IRTH

.

V

ARIABLE

R

ELATIVE

R

ISK

(95% CI)*

FIRST

ADJUSTMENT SECOND

ADJUSTMENT

THIRD

ADJUSTMENT

(

FULL

MODEL

)

Family history

Parent

Father affected, mother affected

Father affected, mother not affected

Father not affected, mother affected

Father not affected, mother not affected

Father unknown, mother affected

Father unknown, mother not affected

Sibling

One or more affected siblings

No affected siblings

65.49 (24.55174.73)

8.34 (5.9111.76)

11.33 (8.8414.53)

1.00

20.99 (12.5935.00)

2.48 (2.142.88)

9.04 (6.9711.72)

1.00

59.74 (22.39159.45)

7.97 (5.6511.24)

10.19 (7.9313.09)

1.00

17.12 (10.2428.64)

2.45 (2.112.84)

7.33 (5.639.53)

1.00

46.90 (17.56125.26)

7.20 (5.1010.16)

9.31 (7.2411.96)

1.00

14.18 (8.4823.70)

2.00 (1.722.32)

6.99 (5.389.09)

1.00

Other factors

Place of birth

Capital

Suburb of capital

Provincial city (>100,000 population)

Provincial town (>10,000 population)

Rural area

Greenland

Other countries

Unknown

Season of birth (amplitude of sine function)

2.49 (2.212.80)

1.64 (1.401.93)

1.57 (1.361.81)

1.24 (1.101.41)

1.00

3.71 (2.036.75)

3.52 (2.744.52)

1.28 (0.483.42)

1.12 (1.061.18)

2.49 (2.202.80)

1.64 (1.401.93)

1.57 (1.361.81)

1.24 (1.101.41)

1.00

3.71 (2.046.76)

3.52 (2.734.52)

1.26 (0.473.39)

1.11 (1.061.18)

2.40 (2.132.70)

1.62 (1.371.90)

1.57 (1.361.81)

1.24 (1.101.41)

1.00

3.71 (2.046.76)

3.45 (2.694.44)

1.22 (0.463.27)

1.11 (1.061.18)

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

606

Febr uar y 25, 1999

The New Engl and Jour nal of Medi ci ne

was more important in association with birth in a

suburb of the capital or in a provincial town and less

so in association with birth in the capital, a provin-

cial city, or a rural area.

There were no interactions between sex or age

and the variables shown in Table 2. Exclusion of the

youngest age group (5 to 14 years), in which the risk

of schizophrenia was very low, resulted in no chang-

es in the risk estimates or only minor changes (data

not shown).

The population attributable risks associated with

the risk factors in the full model are shown in Table

3. A family history of schizophrenia accounted for

5.5 percent of the cases of schizophrenia, the season

of birth accounted for 10.5 percent, and an urban

place of birth accounted for 34.6 percent. The risk

factors in Table 3 are not mutually exclusive, and the

estimates of attributable risk are not additive.

DISCUSSION

Schizophrenia in a parent or sibling was associated

with the highest risk of schizophrenia in this study.

The estimate of the risk associated with a family his-

tory of schizophrenia could have been artificially in-

creased if clinicians were more likely to diagnose the

disorder in a person with one or more family mem-

bers who had the same disorder than in a person

with no affected family members. However, our risk

estimates were very similar to those in studies that

used standardized diagnostic procedures and case-

finding methods that were independent of psychiat-

ric treatment.

1,10

Therefore, we do not believe that

this potential bias had any substantial effect on our

results.

Some studies have reported higher rates of schizo-

phrenia among the relatives of female patients with

schizophrenia than among the relatives of male pa-

tients with schizophrenia.

23

However, in line with a

population-based study reported in 1995,

24

we found

no support for such differences. Our finding of an

excess number of men with schizophrenia is consis-

tent with the results of other register-based stud-

ies.

25

The effects of the risk factors included in our

study were identical for men and women.

We found a twofold increase in the risk of schizo-

phrenia among persons with unknown fathers as

compared with persons with known fathers without

schizophrenia. This difference might be explained

by the lower socioeconomic status of the mothers of

these offspring or by difficulties in growing up in a

family without a father. If the difference was due to

a higher proportion of cases of schizophrenia among

unknown fathers, at least 16 percent of the fathers

of the 46,766 offspring with unknown fathers must

have had schizophrenia. Such a large proportion of

unknown fathers with schizophrenia is highly un-

likely, since it is of the same order of magnitude as

the total number of men hospitalized during the

study period for schizophrenia in Denmark. We

must conclude that there is no strong empirical evi-

dence to support any of these hypotheses, although

the finding itself seems to be robust.

The prevalence of schizophrenia is higher in ur-

ban areas than in rural areas.

7,26,27

The difference has

been ascribed to selective migration from rural to

urban areas before the onset of schizophrenia, but

this hypothesis does not explain our finding of a

higher risk among people born in urban areas. Oth-

er possible explanations include increased exposure

to infections during pregnancy and childhood be-

cause of more crowded living conditions or more

perinatal complications in urban areas. Alternatively,

one could hypothesize that persons with an unex-

Figure 1.

Relative Risk of Schizophrenia According to Month of

Birth.

The data points and vertical bars show the relative risks and 95

percent confidence intervals, respectively, with the month of

birth analyzed as a categorical variable, and the curve shows

the relative risk as a fitted sine function of the month of birth.

The reference category is December.

0.6

1.4

D

e

c

e

m

b

e

r

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.2

1.3

F

e

b

r

u

a

r

y

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

M

a

r

c

h

A

p

r

i

l

M

a

y

J

u

n

e

J

u

l

y

A

u

g

u

s

t

S

e

p

t

e

m

b

e

r

O

c

t

o

b

e

r

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

Month of Birth

R

e

l

a

t

i

v

e

R

i

s

k

T

ABLE

3.

P

OPULATION

A

TTRIBUTABLE

R

ISK

A

CCORDING TO FAMILY HISTORY, PLACE OF BIRTH,

AND SEASON OF BIRTH.

VARIABLE

POPULATION

ATTRIBUTABLE

RISK (%)

Schizophrenia in one or both parents 3.8

Schizophrenia in one or more siblings 1.9

Schizophrenia in parent or sibling 5.5

Place of birth 34.6

Season of birth 10.5

Place and season of birth 41.4

All variables listed above 46.6

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

EFFECTS OF FAMI LY HI STORY AND PLACE AND SEASON OF BI RTH ON THE RI SK OF SCHI ZOPHRENI A

Vol ume 340 Number 8 607

pressed genetic predisposition for schizophrenia are

more likely to migrate to urban areas, but a family

history of schizophrenia does not explain or affect

the urbanrural differences we observed. Further-

more, we estimated that if the risk of schizophrenia

for persons born in the capital or its suburbs as com-

pared with the risk for those born elsewhere in Den-

mark (relative risk, 1.74) could be explained by the

presence of undiagnosed schizophrenia in parents,

9.5 percent of the 435,124 children who were born

in the capital or its suburbs must have had a parent

who transmitted a genetic risk equal to that trans-

mitted by a parent with diagnosed schizophrenia.

This proportion seems unrealistically high. Finally,

differences in the availability of psychiatric services

might explain urbanrural differences. This seems

unlikely, however, because distances are small in Den-

mark, services are free, and place of birth, not place

of residence, was the variable studied.

An interesting finding was the highly increased

risk of schizophrenia in persons born to Danish wom-

en outside Denmark. This increase is probably not

due to a tendency for mentally ill parents to leave

the country temporarily, since the mothers and fa-

thers of these persons did not have an increased like-

lihood of having schizophrenia. A possible explana-

tion is the theory proposed by Wessely et al.

28

These

authors reported an increased risk of schizophrenia

in second-generation black Caribbean immigrants

living in London and suggested that it could be ex-

plained by maternal exposure to infective agents un-

common in their country of origin.

The effect of season of birth on the risk of schizo-

phrenia was of the expected magnitude and had the

expected periods of maximal risk (February and

March) and minimal risk (August and September).

6

We replicated a previous finding that there was no

interaction between season of birth and family his-

tory of schizophrenia.

29

However, we did not repli-

cate a previous finding that the association between

winter birth and schizophrenia occurred only among

persons born in urban areas.

30

Lewis

31

suggested that

an association between the season of birth and

schizophrenia is a methodologic artifact due to the

so-called ageincidence effect that is, persons

born in January are older than those born later in

the year within the same age category and thus have

spent more time at risk for schizophrenia. This con-

cern was not relevant to our cohort study, however,

since all age-specific personyears were calculated

exactly for each person.

There is strong evidence that the most important

risk factors in families with more than one affected

member are genetic.

32,33

However, the absence of

consistent interactions between the family-history

variables and the variables that are less likely to be

genetically determined means that our results do not

support the notion that birth in February or March

and an urban place of birth are less important risk

factors in cases in which there is a family history of

schizophrenia.

Although a family history of schizophrenia was

the strongest risk factor in terms of relative risk, by

far the most important factors in terms of attribut-

able risk were the place of birth and the season of

birth. Obviously, neither of these factors is relevant

as a direct basis for intervention, nor are they plau-

sible in terms of biologically meaningful exposure

affecting the human brain. Instead, place and season

of birth must be seen as proxy variables for factors

that contribute more directly to the risk of schizo-

phrenia. Our estimates of attributable risk do not ex-

clude the possibility that genetic factors are neces-

sary causes of schizophrenia in most or all cases.

They do, however, suggest that such factors are not

sufficient and that environmental factors are major

determinants of schizophrenia.

Supported by the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation and the Dan-

ish National Research Foundation.

We are indebted to Dr. A. Bertelsen for his helpful comments and

suggestions.

REFERENCES

1. Gottesman II. Schizophrenia genesis: the origins of madness. New York:

W.H. Freeman, 1991.

2. Kendler KS, Diehl SR. The genetics of schizophrenia: a current, genet-

ic-epidemiologic perspective. Schizophr Bull 1993;19:261-85.

3. McNeil TF. Perinatal risk factors and schizophrenia: selective review and

methodological concerns. Epidemiol Rev 1995;17:107-12.

4. Geddes JR, Lawrie SM. Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: a

meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:786-93.

5. Barr CE, Mednick SA, Munk-Jorgensen P. Exposure to influenza epi-

demics during gestation and adult schizophrenia: a 40-year study. Arch

Gen Psychiatry 1990;47:869-74.

6. Cotter D, Larkin C, Waddington JL, OCallaghan E. Season of birth in

schizophrenia: clue or cul-de-sac? In: Waddington JL, Buckley PF, eds. The

neurodevelopmental basis of schizophrenia. Austin, Tex.: R.G. Landes,

1996:17-30.

7. Lewis G, David A, Andreasson S, Allebeck P. Schizophrenia and city

life. Lancet 1992;340:137-40.

8. Eaton WW, Day R, Kramer M. The use of epidemiology for risk factor

research in schizophrenia: an overview and methodologic critique. In:

Tsuang MT, Simpson JC, eds. Nosology, epidemiology and genetics of

schizophrenia. Vol. 3 of Handbook of schizophrenia. Amsterdam: Elsevier,

1988:169-204.

9. Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology in psychiatry: taking both genes and

environment seriously. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:895-9.

10. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, OHare A, Spellman M,

Walsh D. The Roscommon Family Study. I. Methods, diagnosis of

probands, and risk of schizophrenia in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;

50:527-40.

11. Malig C. The civil registration system in Denmark. IIVRS technical pa-

pers no. 66. Bethesda, Md.: International Institute for Vital Registration

and Statistics, December 1996:1-9.

12. Westergaard T, Andersen PK, Pedersen JB, et al. Birth characteristics,

sibling patterns, and acute leukemia risk in childhood: a population-based

cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:939-47.

13. Munk-Jrgensen P, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central

Register. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:82-4.

14. Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries,

and causes of death. Vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1967.

15. Glossary of mental disorders and guide to their classification. Geneva:

World Health Organization, 1974.

16. Munk-Jrgensen P. Faldende frstegangsindlggelsesrater for skizo-

freni i Danmark 19701991. (Doctoral dissertation. rhus, Denmark:

rhus University, 1995.)

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

608 Febr uar y 25, 1999

The New Engl and Jour nal of Medi ci ne

17. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Vol. 2.

The design and analysis of cohort studies. Lyon, France: International

Agency for Research on Cancer, 1987. (IARC scientific publications no. 82.)

18. The GENMOD procedure. In: SAS/STAT software: changes and en-

hancements for release 6.12. Cary, N.C.: SAS Institute, 1996:23-41.

19. Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: John Wiley, 1990.

20. Breslow NE. Generalized linear models: checking assumptions and

strengthening conclusions. Stat Applicata 1996;8:23-41.

21. Clayton D, Hills M. Statistical models in epidemiology. Oxford, Eng-

land: Oxford University Press, 1993.

22. Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Schairer C. Estimating the

population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control da-

ta. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:904-14.

23. Goldstein JM, Faraone SV, Chen WJ, Tolomiczencko GS, Tsuang MT.

Sex differences in the familial transmission of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry

1990;156:819-26.

24. Kendler KS, Walsh D. Gender and schizophrenia: results of an epide-

miologically-based family study. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:184-92.

25. Jablensky A, Eaton WW. Schizophrenia. Baillieres Clin Psychiatry

1995;1:283-306.

26. Takei N, Sham PC, OCallaghan E, Glover G, Murray RM. Schizo-

phrenia: increased risk associated with winter and city birth a case-con-

trol study in 12 regions within England and Wales. J Epidemiol Commu-

nity Health 1995;49:106-7.

27. Torrey EF, Bowler A. Geographical distribution of insanity in America:

evidence for an urban factor. Schizophr Bull 1990;16:591-604.

28. Wessely S, Castle D, Der G, Murray R. Schizophrenia and Afro-Car-

ibbeans: a case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 1991;159:795-801.

29. Hettema JM, Walsh D, Kendler KS. Testing the effect of season of

birth on familial risk for schizophrenia and related disorders. Br J Psychia-

try 1996;168:205-9.

30. OCallaghan E, Gibson T, Colohan HA, et al. Season of birth in

schizophrenia: evidence for confinement of an excess of winter births to

patients without a family history of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1991;

158:764-9.

31. Lewis MS. Age incidence and schizophrenia. I. The season of birth

controversy. Schizophr Bull 1989;15:59-73.

32. Gottesman I, Bertelsen A. Confirming unexpressed genotypes for

schizophrenia: risks in the offspring of Fischers Danish identical and fra-

ternal discordant twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:867-72.

33. Kendler K. Familial risk factors and the familial aggregation of psychi-

atric disorders. Psychol Med 1990;20:311-9.

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on June 10, 2014. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 1999 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Summary & Study Guide - The Gene Machine: How Genetic Technologies Are Changing the Way We Have Kids - and the Kids We HaveFrom EverandSummary & Study Guide - The Gene Machine: How Genetic Technologies Are Changing the Way We Have Kids - and the Kids We HaveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- CH13 Naughty Sex Ideas in MarriageDocument11 pagesCH13 Naughty Sex Ideas in MarriageTheVeiledGarden100% (2)

- Missionary PositionDocument11 pagesMissionary Positionnathan100% (1)

- Helping Sexually Reactive ChildrenDocument14 pagesHelping Sexually Reactive ChildrenEpen Latupeirissa100% (1)

- Research Paper SampleDocument56 pagesResearch Paper Samplekeilah reyes100% (3)

- Courtenay GenealogyDocument8 pagesCourtenay GenealogyJeff MartinNo ratings yet

- Certificate Not A 4ps MemberDocument4 pagesCertificate Not A 4ps Membertarry moreNo ratings yet

- C3h - 7 Jison v. CADocument3 pagesC3h - 7 Jison v. CAAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Husband Filing Divorce Petition Is No Justification For Wife To Lodge False Criminal Cases Against Him and His Family - Bombay HCDocument81 pagesHusband Filing Divorce Petition Is No Justification For Wife To Lodge False Criminal Cases Against Him and His Family - Bombay HCLive Law100% (3)

- General Education English Exam ReviewDocument6 pagesGeneral Education English Exam ReviewRogen HemodoNo ratings yet

- Child Case Study 2Document7 pagesChild Case Study 2api-314700266No ratings yet

- Pedersen 2001Document8 pagesPedersen 2001anca_szaboNo ratings yet

- Artigo JAMADocument7 pagesArtigo JAMAVanessa LealNo ratings yet

- 2012 Parner Etal AnnalsofEpidemiologDocument8 pages2012 Parner Etal AnnalsofEpidemiologV_FreemanNo ratings yet

- English 1Document8 pagesEnglish 1tamijeba89No ratings yet

- Ni Hms 804361Document11 pagesNi Hms 804361Makhda Nurfatmala LubisNo ratings yet

- Maternal Effect Epilepsy Risk Offspring StudyDocument10 pagesMaternal Effect Epilepsy Risk Offspring StudyCONSTANTIUS AUGUSTONo ratings yet

- Síndromes de Anomalías en Cromosomas SexualesDocument9 pagesSíndromes de Anomalías en Cromosomas SexualesIscoMoragaNo ratings yet

- Prabhat Cleft 8Document11 pagesPrabhat Cleft 8drrishavNo ratings yet

- (Article) A Population-Based Study of Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination and AutismDocument6 pages(Article) A Population-Based Study of Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination and AutismReniza ZulkarnaenNo ratings yet

- Fazel 2014 CORRECTE PDFDocument11 pagesFazel 2014 CORRECTE PDFMargaNo ratings yet

- Induced 1 SttrimesterabortionDocument7 pagesInduced 1 Sttrimesterabortionapi-310441322No ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0034866Document4 pagesJournal Pone 0034866Seki MuminovicNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Autism. Perinatal Factors Parental Psychiatric History and Socioeconomic StatusDocument10 pagesRisk Factors For Autism. Perinatal Factors Parental Psychiatric History and Socioeconomic StatusJulio CesarNo ratings yet

- The Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Young ChildrenDocument11 pagesThe Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Young ChildrenanggiNo ratings yet

- EpidemioDocument6 pagesEpidemioFlavian Costin NacladNo ratings yet

- Ensefalitis 9Document4 pagesEnsefalitis 9Asri RachmawatiNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 2010 - Nakaya - Increased Risk of Severe Depression in Male Partners of Women With Breast CancerDocument8 pagesCancer - 2010 - Nakaya - Increased Risk of Severe Depression in Male Partners of Women With Breast CancerVera El Sammah SiagianNo ratings yet

- Childhood Asthma Is Associated With Development of Type 1 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Danish Nationwide Registry StudyDocument9 pagesChildhood Asthma Is Associated With Development of Type 1 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Danish Nationwide Registry Studykholoud mohamedNo ratings yet

- An Epidemiological Study of Head Injuries in A UK Population Attending An Emergency DepartmentDocument3 pagesAn Epidemiological Study of Head Injuries in A UK Population Attending An Emergency DepartmentDianitaGaravitoVargasNo ratings yet

- Childhood Adverse Life Events and Parental Psychopathology As Risk Factors For Bipolar DisorderDocument6 pagesChildhood Adverse Life Events and Parental Psychopathology As Risk Factors For Bipolar Disordercesia leivaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Hypospadias: Original PaperDocument8 pagesRisk Factors For Hypospadias: Original Papermustafi28No ratings yet

- MPA Next Phase of ResearchDocument1 pageMPA Next Phase of ResearchashfaqamarNo ratings yet

- DEPRESIADocument9 pagesDEPRESIACojocaru Cristina IoanaNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia review of molecular geneticsDocument18 pagesSchizophrenia review of molecular geneticsmustafa566512345No ratings yet

- Health of Children Born To Mothers Who Had Preeclampsia: A Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesHealth of Children Born To Mothers Who Had Preeclampsia: A Population-Based Cohort StudyAdhitya Pratama SutisnaNo ratings yet

- Neuro J 1Document11 pagesNeuro J 1Anonymous CtjSRA4No ratings yet

- Prevalence and Characteristics of Children With Cerebral Palsy in EuropeDocument8 pagesPrevalence and Characteristics of Children With Cerebral Palsy in EuropeFachry MuhammadNo ratings yet

- kww009 PDFDocument10 pageskww009 PDFsaniya ashilahNo ratings yet

- Madsen 2003Document3 pagesMadsen 2003fuck youNo ratings yet

- GeneticHeritability 2011 07 04Document8 pagesGeneticHeritability 2011 07 04Ni Mas Ayu GandasariNo ratings yet

- SIG en SaludDocument7 pagesSIG en SaludMarvin Osli KafatyNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2004 Caulfield 193 8Document6 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2004 Caulfield 193 8Seik Soi100% (1)

- Cerebral Palsy Among Children of Immigrants in Denmark and The Role of Socioeconomic StatusDocument10 pagesCerebral Palsy Among Children of Immigrants in Denmark and The Role of Socioeconomic StatusAlisa Fatikha RNo ratings yet

- BMC Public Health: Down Syndrome, Paternal Age and Education: Comparison of California and The Czech RepublicDocument10 pagesBMC Public Health: Down Syndrome, Paternal Age and Education: Comparison of California and The Czech RepublicHalimatus Sa'diyahhNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2006 Choudhuri 349 56Document10 pagesPediatrics 2006 Choudhuri 349 56Degunz LubisNo ratings yet

- Trend and Outcome of Sepsis in ChildrenDocument8 pagesTrend and Outcome of Sepsis in ChildrenGunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- Bronchiectasis New ZealandDocument4 pagesBronchiectasis New ZealandshevinesaNo ratings yet

- Access The Most Recent Version at DOIDocument37 pagesAccess The Most Recent Version at DOIAlvinRenaldoTanjayaNo ratings yet

- Nationwide prevalence of familial IPF in Finland suggests founder effectDocument5 pagesNationwide prevalence of familial IPF in Finland suggests founder effectNailatul Izza HumammyNo ratings yet

- Gender 22Document4 pagesGender 22andi tzamrah istiqani syamNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Minotrity StatusDocument11 pagesEthnic Minotrity StatusFabiana H. ShimabukuroNo ratings yet

- Risk of Oral Clefts in TwinsDocument7 pagesRisk of Oral Clefts in Twinsedward iskandarNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of SchizophreniaDocument13 pagesEpidemiology of SchizophreniaSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Hovatta 1997Document8 pagesHovatta 1997JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Captura de Pantalla 2024-01-23 A La(s) 11.26.43Document9 pagesCaptura de Pantalla 2024-01-23 A La(s) 11.26.43Dany MorBenNo ratings yet

- Birth Seasonality in Schizophrenia: Effects of Gender and Income StatusDocument8 pagesBirth Seasonality in Schizophrenia: Effects of Gender and Income StatusDelfinaNo ratings yet

- Death and SuicideDocument11 pagesDeath and SuicideRoberto SalvatierraNo ratings yet

- Grosen 2010Document7 pagesGrosen 2010edward iskandarNo ratings yet

- Autismo EgiptoDocument8 pagesAutismo EgiptoOvsd Vfsg SDNo ratings yet

- Early Adolescents' HIV-related Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour in FinlandDocument8 pagesEarly Adolescents' HIV-related Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour in Finlandaccord123No ratings yet

- J Hum ReprodDocument7 pagesJ Hum ReprodFrisky BadiNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Children: Associations With Obesity, Race, and Respiratory ProblemsDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Children: Associations With Obesity, Race, and Respiratory ProblemsMiral BassNo ratings yet

- Riesgos en VSRDocument11 pagesRiesgos en VSRlorena mirielisNo ratings yet

- Epidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.Document9 pagesEpidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.marioNo ratings yet

- Rhinovirus Wheezing Illness and Genetic Risk of Childhood-Onset AsthmaDocument10 pagesRhinovirus Wheezing Illness and Genetic Risk of Childhood-Onset AsthmaEphy HaningNo ratings yet

- Yoa 8230Document7 pagesYoa 8230FortuneNo ratings yet

- Allergy Associated with Increased Risk of Suicide Completion, Especially in Absence of Mood DisorderDocument12 pagesAllergy Associated with Increased Risk of Suicide Completion, Especially in Absence of Mood DisordermaelisonNo ratings yet

- (1479683X - European Journal of Endocrinology) Incidence of GH Deficiency - A Nationwide StudyDocument11 pages(1479683X - European Journal of Endocrinology) Incidence of GH Deficiency - A Nationwide StudysavitageraNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices On HIV/AIDS and Prevalence of HIV in The General Population of Sucre, BoliviaDocument13 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes and Practices On HIV/AIDS and Prevalence of HIV in The General Population of Sucre, BoliviaRima AnggreniNo ratings yet

- Mini Project InternshipDocument11 pagesMini Project InternshipAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- 0 OijhDocument1 page0 OijhAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Acute Scrotum CAMPBELLDocument9 pagesAcute Scrotum CAMPBELLAnastasia Febrianti100% (1)

- Acute Scrotum - Etiology and ManagementDocument0 pagesAcute Scrotum - Etiology and ManagementNikolaus TalloNo ratings yet

- The Acute ScrotumDocument9 pagesThe Acute ScrotumAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 40 Neuro-SurgeryDocument43 pagesChapter 40 Neuro-SurgeryAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- 3 RytyjDocument1 page3 RytyjAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- LamDocument31 pagesLamAnastasia Febrianti100% (1)

- Kriteria AkiDocument1 pageKriteria AkiAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 40 Neuro-SurgeryDocument43 pagesChapter 40 Neuro-SurgeryAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2005 Broderick 341 4Document4 pagesCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2005 Broderick 341 4Anastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Dme 12392Document12 pagesDme 12392Anastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Nej Me 058200Document3 pagesNej Me 058200Anastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Decreased cerebral lateralization in schizophrenia meta-analysisDocument9 pagesDecreased cerebral lateralization in schizophrenia meta-analysisAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- BJP 2000 Browne 173 6Document5 pagesBJP 2000 Browne 173 6Anastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- BJP 2001 Adams 290 9Document11 pagesBJP 2001 Adams 290 9Anastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Morning Report: Supervisor Dr. Sabar P. Siregar, SP - KJDocument40 pagesMorning Report: Supervisor Dr. Sabar P. Siregar, SP - KJAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Case Report: The Active Management of Impending Cephalopelvic Disproportion in Nulliparous Women at Term: A Case SeriesDocument6 pagesCase Report: The Active Management of Impending Cephalopelvic Disproportion in Nulliparous Women at Term: A Case SeriesAnastasia FebriantiNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Family Health NursingDocument44 pagesModule 3 Family Health Nursing17melrosefloresNo ratings yet

- Los Pronombres Sujetos2Document1 pageLos Pronombres Sujetos2KariLeeNo ratings yet

- Rocha vs. Tuason and Rocha, de Despujols.: 976 Philippine Reports AnnotatedDocument8 pagesRocha vs. Tuason and Rocha, de Despujols.: 976 Philippine Reports AnnotatedTEtchie TorreNo ratings yet

- Đề 53 I. Multiple Choice (8Pts)Document6 pagesĐề 53 I. Multiple Choice (8Pts)Nguyên TrầnNo ratings yet

- PollensDocument13 pagesPollensAdam AcostaNo ratings yet

- 11 History Notes 05 Nomadic Empires PDFDocument5 pages11 History Notes 05 Nomadic Empires PDFAnjali RanaNo ratings yet

- Expected Linear Seating Arrangement With Blood Relation For SbiDocument24 pagesExpected Linear Seating Arrangement With Blood Relation For SbiADARSH PRIYANo ratings yet

- Female FoeticideDocument5 pagesFemale FoeticideamritpalghattaoraeNo ratings yet

- Full Report Ewc661Document18 pagesFull Report Ewc661Athirah DinataNo ratings yet

- Crim 2 - Title Viii Compilation of Cases and Special LawsDocument214 pagesCrim 2 - Title Viii Compilation of Cases and Special LawsjiggerNo ratings yet

- Freud's Personality StructureDocument36 pagesFreud's Personality StructureSara AliNo ratings yet

- As AngolanasDocument137 pagesAs AngolanasEliane MaiaNo ratings yet

- Personal Laws IIDocument12 pagesPersonal Laws IIAtulNo ratings yet

- HISTORY of INDIA - Kalachuri Dynasty SanjuDocument10 pagesHISTORY of INDIA - Kalachuri Dynasty SanjuSanjiv GautamNo ratings yet

- LESSON+10+-+Motivation 1Document25 pagesLESSON+10+-+Motivation 1yenzelNo ratings yet

- Tax Oo2Document2 pagesTax Oo2HURLY BALANCARNo ratings yet

- WB. Unit 3.extended Family. 2020Document10 pagesWB. Unit 3.extended Family. 2020neyNo ratings yet

- Family: The Meaning, Features, Types and FunctionsDocument23 pagesFamily: The Meaning, Features, Types and FunctionsShing Mae MarieNo ratings yet

- English For - Students Kaushanskaya - ExercisesDocument174 pagesEnglish For - Students Kaushanskaya - ExercisesSignorinaNo ratings yet

- Percy Bysshe Shelley: Poet of RomanticismDocument20 pagesPercy Bysshe Shelley: Poet of RomanticismAnurag SinghNo ratings yet