Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Espino Vs National Labor Relations Commission (240 SCRA 52)

Uploaded by

Enan IntonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Espino Vs National Labor Relations Commission (240 SCRA 52)

Uploaded by

Enan IntonCopyright:

Available Formats

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. Nos. 109642-43 January 5, 1995

LESLIE W. ESPINO, petitioner,

vs.

HON. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION and PHILIPPINE AIR

LINES, respondents.

ROMERO, J .:

The controversy generated in the instant case once again calls for the resolution of the issue of

whether or not the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) has jurisdiction over a

complaint filed by a corporate Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer for illegal

dismissal resulting from the termination of his services as such officer by virtue of four (4)

separate resolutions of the Board of Directors Air Lines (PAL).

The undisputed facts are as follows:

Petitioner Leslie W. Espino was the Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer of private

respondent Philippine Airlines (PAL) when his services were terminated sometime in December

1990 by the Board of Directors of PAL as a result of the findings of the panels created by then

President Corazon C. Aquino to investigate the administrative charges filed against him and

other senior officers for their purported involvement in four, denominated "Goldair," "Robelle,"

"Kasbah/La Primavera," and "Middle East" which allegedly prejudiced the interests of both PAL

and the Philippine Government.

Petitioner started his employment with PAL on February 25, 1960 as a Traffic and Sales Trainee

and, for 30 years, was successively promoted

1

until he became, by virtue of an election in March

1988 conducted by the Board of Directors, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

for a term of one (1) year and who holds said office until his successor is elected and qualified,

pursuant to Section 7, Article III in relation to Section 1, Article IV of the Amended By-Laws of

PAL. The last time he was elected as such was on October 20, 1989.

Sometime on July 2, 1990, petitioner and several other senior officers of PAL were

administratively charged by Romeo S. David, Senior Vice President for Corporate Services and

Logistics Group, for their purported involvement in four cases, labelled as "Goldair," "Robelle,"

"Kasbah/Primavera" and "Middle East."

Except for the conflict of interest charges in the "Robelle" case, petitioner and several other

senior officers of PAL were uniformly charged in the three (3) other aforementioned cases of

gross incompetence, mismanagement, inefficiency, negligence, mismanagement, dereliction of

duty, failure to observe and/or implement administrative and executive policies, and related acts

or omissions resulting in the concealment or coverup and prevention of the seasonable discovery

of anomalous transactions which, as a consequence, caused prejudice to the best interest of PAL

and the Government.

Pending investigation by the panels created by then President Corazon C. Aquino, petitioner and

other senior officers of PAL were placed under suspension by the Board of Directors.

On October 19, 1990, during the organizational meeting of the PAL Board of Directors, the

election or appointment of some senior officers of the company who, like petitioner, had been

charged administratively with various offenses and accordingly suspended, were deferred by the

Board of Directors. During the said organizational meeting, Feliciano Belmonte was elected

Chairman of the Board while Dante Santos was elected as President and Chief Executive Officer.

On the basis of the findings submitted by the presidential investigating panels, the Board issued

separate resolutions dated January 19, 1991 in the "Goldair," "Robelle," and Kasbah/La

Primavera," cases and another dated August 9, 1991 in the "Middle East" case wherein petitioner

was considered resigned from the service effective immediately for loss of confidence and for

acts inimical to the interests of the company.

As a result of his termination, petitioner Espino filed a complaint for illegal dismissal against

PAL with the National Labor Relations Commission, Arbitration Branch, NCR, praying, among

others, for reinstatement with backwages, recovery of P50 Million as moral damages, P10

Million as exemplary damages and attorney's fees. The case was docketed as NLRC Case No.

00-05-03210-91.

PAL justified the legality of petitioner Espino's dismissal from the service before the Labor

Arbiter but questioned the jurisdiction of the NLRC contending that, because the investigating

panels were created by President Corazon C. Aquino, it became, together with the PAL Board of

Directors, a "parallel arbitration unit" which substituted the NLRC. As such, PAL argued that

since the Board resolutions of the aforesaid cases; cannot be reviewed by the NLRC, the recourse

of petitioner Espino should have been addressed, by way of an appeal, to the Office of the

President of the Republic of the Philippines.

On February 20, 1992, Labor Arbiter Cresencio J. Ramos rendered a decision

2

finding that

petitioner Espino was dismissed just and valid cause and accordingly ordered his reinstatement

to his former position as Executive Vice-President-Chief Operating Officer without loss of

seniority rights plus full backwages and other benefits appurtenant thereto, without qualification

or deduction from the time of his illegal dismissal up to the date of his actual reinstatement. The

dispositive portion reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered:

1. Ordering complainant's immediate reinstatement to his former position as

Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer without loss of seniority rights

plus full backwages and other benefits appurtenant thereto, without qualification

or deduction, from the time of his illegal dismissal up to the time of his actual

reinstatement. His backwages as of February 29, 1992 as computed are in the total

sum of P2,925,000.00 (P195,000.00 x 15 months, including the one month

suspension).

2) Ordering respondent PAL to pay complainant Leslie Espino the following sums:

a) Backwages as of February 1992 P2,925,000.00

b) Cash equivalent of Annual trip passes

on first class, (1 for international, 1

for regional, and 1 for domestic)

for complainant, his spouse,

qualified dependent and parents

worth approximately US $45,000.00

at current rate of exchange rate of

exchange P26.50/dollar 1,192,000.00

c) Midyear and Christmas bonuses

equivalent to two (2) months pay 390,000.00

3 Awarding moral damages to complainant in

the sum of P20 million plus exemplary damages of P2.0 22,000,000.00

TOTAL P26,507,000.00

4 Granting attorney's fees of 10% of the total monetary award 2,650,700

GRAND TOTAL P28,157,700.00

From the said decision, PAL filed on March 5, 1992 an appeal with the NLRC and submitted on

March 13, 1992 a supplemental memorandum on appeal. PAL argued that the Labor Arbiter's

decision is null and void for lack of jurisdiction over the subject matter as it is the Securities and

Exchange Commission, and not the NLRC, which has original and exclusive jurisdiction over

cases involving dismissal or removal of corporate officers.

Earlier, or more specifically, on February 25, 1992, petitioner Espino filed a motion for issuance

of writ of execution on the ground that the decision of the Labor Arbiter ordering reinstatement

is immediately executory even pending appeal pursuant to Article 223 of the Labor Code, as

amended.

On February 28, 1992, the Labor Arbiter issued a writ of execution.

PAL, for its part, filed a motion to quash the writ of execution reiterating its argument that the

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and not the NLRC has original and exclusive

jurisdiction over the subject matter involving the dismissal or removal of corporate officers.

On March 31, 1992, after an exchange of pleadings, Labor Arbiter Ramos denied PAL's motion

to quash the writ of execution. Thereafter, or on April 2, 1992, an alias writ of execution was

issued.

PAL then filed on April 23, 1992 with the NLRC a petition for injunction, later amended to

implead the Labor Arbiter, praying for the issuance of a temporary restraining order to enjoin the

enforcement of said alias writ of execution.

On April 27, 1992, the NLRC issued a temporary restraining order enjoining Espino, Sheriff

Anam Timbayan, their agents and all persons acting under them, from implementing the alias

writ of execution issued on April 2, 1992 upon PAL's posting of P400,000.00 cash or surety

bond. On May 5, 1992, PAL posted the P400,000.00 surety bond.

On July 31, 1992, the NLRC promulgated a resolution

3

dismissing the complaint for illegal

dismissal for lack of jurisdiction and declaring the nullity of the alias writ of execution.

Petitioner Espino, Labor Arbiter Cresencio Ramos and Sheriff Anam Timbayan were

permanently enjoined from enforcing the said alias writ of execution.

Petitioner Espino filed a motion for reconsideration but the same was denied on January 8,

1993.

4

Dissatisfied, petitioner filed the instant petition for certiorari contending mainly that it is the

NLRC which has jurisdiction under Article 217, par. (2) of the Labor Code, as amended, to hear

the illegal dismissal case he filed against PAL as it involves the termination of a regular and

permanent employee and the issues in the dispute involved, not only his removal from office, but

also his claim for backwages and other benefits and damages; that PAL is estopped from

questioning the jurisdiction of the NLRC.

We rule that the petition lacks merit.

The Court, citing Presidential Decree No. 902-A, laid down the rule in the case of Philippine

School of Business Administration v. Leano,

5

and consequently reiterated in three (3) other

cases

6

that it is the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and not the NLRC which has

original and exclusive jurisdiction over cases involving the removal from employment of

corporate officers.

Sec. 5. of Presidential Decree No. 902-A regarding the jurisdiction of the Securities and

Exchange Commission provides, as follows:

Sec. 5. In addition to the regulatory and adjudicative functions of the Securities

and Exchange Commission over corporations, partnerships and other forms of

associations registered with it as expressly granted under existing laws and

decrees, it shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction to hear and decide cases

involving:

(a) Devices or schemes employed by or any acts of the board of

directors, business associates, its officers or partners, amounting to

fraud and misrepresentation which may be detrimental to the

interest of the public and/or of the stockholders, partners, members

of associations or organizations registered with the Commission.

(b) Controversies arising out of intracorporate or partnership

relations, between and among stockholders, members, or

associates; between any or all of them and the corporation,

partnership or association of which they are stockholders,

members, or associates, respectively; and between such

corporation, partnership or association and the state insofar as it

concerns their individual franchise or right to exist as such entity.

(c) Controversies in the election or appointments of directors,

trustees, officers or managers of such corporations, partnerships or

associations.

(d) Petitions of corporations, partnerships or associations to be

declared in the state of suspension of payments in cases where the

corporation, partnership or association possesses sufficient

property to cover all its debts but foresees the impossibility of

meeting them when they respectively fall due or in cases where the

corporation, partnership or association has no sufficient assets to

cover its liabilities, but is under the management of a

Rehabilitation Receiver or Management Committee created

pursuant to this Decree.

In intra-corporate concerning the election or appointment of officers of a corporation, Section 5,

PD 902-A specifically provides:

Sec. 5. In addition to the regulatory and adjudicative functions of the Securities

and Exchange Commission over corporations, partnerships and other forms of

associations registered with it as expressly granted under existing laws and

decrees, it shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction to hear and decide cases

involving:

xxx xxx xxx

(c) Controversies in the election or appointments of directors, trustees, officers or

managers of such corporations, partnerships or associations.

Indisputably, the position of Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer from which

petitioner Espino claims to have been illegally dismissed, is an elective office under Section 7,

Article III is an elective corporate office under Section 1, Article IV of the Amended by-Laws of

PAL. The said corporate office has a fixed term of one (1) year and the one elected shall hold

office until a successor shall have been elected and qualified. He lost that position when his

appointment or election as Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer, together with other

senior officers who were similarly charged administratively, were deferred by the Board of

Directors in its organizational meeting on October 19, 1990. He was later considered by the

Board as resigned from the service, for reasons earlier stated, and the said position was later

abolished.

The matter of petitioner's not being elected to the office of Executive

Vice-President-Chief Operating Officer thus falls squarely within the purview of Section 5 par.

(c) of P.D. 902-A. In the case of PSBA v. Leano, supra, which involved an Executive Vice

President who was not re-elected to the said position during the election of officers on September

5, 1981 by the PSBA's newly elected Board of Directors, the Court emphatically stated:

This is not a case of dismissal. The situation is that of a corporate office having

been declared vacant, and that of TAN's not having been elected thereafter. The

matter of whom to elect is a prerogative that belongs to the Board, and involves

the exercise of deliberate choice and the faculty of discriminative selection.

Generally speaking, the relationship of a person to a corporation, whether as

officer or as agent or employee, is not determined by the nature of the services

performed, but by the incidents of the relationship as they actually exists.

A corporate officer's dismissal is always a corporate act and/or an intra-corporate controversy

and that nature is not altered by the reason or wisdom which the Board of Directors may have in

taking such action.

7

Furthermore, it must be noted that the reason behind the non-election of petitioner to the position

of Executive Vice President-Chief Operating Officer arose from, or is closely connected with,

his involvement in the alleged irregularities in the aforementioned cases which, upon

investigation and recommendation, were resolved by the PAL Board of Directors against him

and other senior officers. Evidently, this intra-corporate ruling places the instant case under the

specialized competence and expertise of the SEC.

The jurisdiction of the SEC has likewise been clarified by this Court in the case of Union Glass

and Container Corporation, et al. v. SEC, et al.,

8

thus:

This grant of jurisdiction must be viewed in the light of the nature and function of

the SEC under the law. Section 3 of PD No. 902-A confers upon the latter

"absolute jurisdiction, supervision, and control over all corporations, partnerships

or associations, who are grantees of primary franchise and/or license or permit

issued by the government to operate in the Philippines . . . ." The principal

function of the SEC is the supervision and control over corporations, partnerships

and associations with the end in view that investment in these entities may be

encouraged and protected, and their activities pursued for the promotion of

economic development.

It is in aid of this office that the adjudicative power of the SEC must be

exercised. Thus the law explicitly specified and delimited its jurisdiction to

matters intrinsically connected with the regulations of corporations, partnerships

and associations and those dealing with the internal affairs of such corporations,

partnerships or associations.

Otherwise stated, in order that the SEC can take cognizance of a case, the

controversy must pertain to any of the following relationships: (a) between the

corporation, partnership or association and the public; (b) between the

corporation, partnership or association and its stockholders, partners, members, or

officers; (c) between the corporation, partnership or association and the state in so

far as its franchise, permit or license to operate is concerned, and (d) among the

stockholders, partners or associates themselves.

The fact that petitioner sought payment of his backwages, other benefits, as well as moral and

exemplary damages and attorney's fees in his complaint for illegal dismissal will not operate to

prevent the SEC from exercising its jurisdiction under PD 902-A. While the affirmative reliefs

and monetary claims sought by petitioner in his complaint may, at first glance, mislead one into

placing the case under the jurisdiction of the Labor Arbiter, a closer examination reveals that

they are actually part of the perquisites of his elective position; hence, intimately linked with his

relations with the corporation. In Dy v. NLRC, et al.,

9

the Court, confronted with the same issue

ruled, thus:

The question of remuneration, involving as it does, a person who is not a mere

employee but a stockholder and officer, an integral part, it might be said, of the

corporation, is not a simple labor problem but a matter that comes within the area

of corporate affairs and management, and is in fact a corporate controversy in

contemplation of the Corporation Code.

The Court has likewise ruled in the case of Andaya v. Abadia

10

that in

intra-corporate matters, such as those affecting the corporation, its directors, trustees, officers

and shareholders, the issue of consequential damages may just as well be resolved and

adjudicated by the SEC. Undoubtedly, it is still within the competence and expertise of the SEC

to resolve all matters arising from or closely connected with all intra-corporate disputes.

Petitioner's reliance on the principle of estoppel to justify the exercise or jurisdiction by the

NLRC over the instant complaint is misplaced. it is not accurate for petitioner to conclude that

PAL did not raise the issue of jurisdiction at the initial stages of the case, for, while it may be

predicated on a different ground, i.e., that appeal from the resolution of the Board of Directors of

PAL as regards termination of his services, is to the Office of the President, PAL did in fact

question the jurisdiction of the Labor Arbiter. An error of this nature, under the circumstances,

could not justify petitioner's insistence that PAL did not raise the issue of jurisdiction at the

outset, but only before the NLRC.

It is well-settled that jurisdiction over the subject matter is conferred by law and the question of

lack of jurisdiction may be raised at anytime even on appeal.

11

The principle of estoppel cannot

be invoked to prevent this Court from taking up the question, which has been apparent on the

face of the pleadings since the start of the litigation before the Labor Arbiter. In the case of Dy

v. NLRC, supra, the Court, citing the case of Calimlim v. Ramirez

12

reiterated that the decision

of a tribunal not vested with appropriate jurisdiction is null and void. Again, the Court

in Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center-Aquaculture Department v. NLRC

13

restated

the rule that the invocation of estoppel with respect to the issue of jurisdiction is unavailing

because estoppel does not apply to confer jurisdiction upon a tribunal that has none over the

cause of action. The instant case does not provide an exception to the said rule.

In fine, the issue of the SEC's jurisdiction is settled and the Court finds it unnecessary to dwell

further on other questions raised by petitioner. Thus, finding no grave abuse of discretion on the

part of NLRC in dismissing the complaint for illegal dismissal, the instant petition must be

dismissed.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition for certiorari is DISMISSED for lack of merit. The

resolution of the National Labor Relations Commission dated July 31, 1992 dismissing the

complaint for illegal dismissal for lack of jurisdiction is AFFIRMED, without prejudice to

petitioner's seeking relief, if so minded, in the proper forum.

SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- SSCR - Surigao City Extension Full PresentationDocument85 pagesSSCR - Surigao City Extension Full PresentationRalna Dyan FloranoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. SandiganbayanDocument104 pagesRepublic vs. SandiganbayanQuennie Jane SaplagioNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law Case Compilation (Chapter 5-7)Document25 pagesAdministrative Law Case Compilation (Chapter 5-7)Sarah Jane-Shae O. Semblante100% (1)

- Remedial Law Case Digests - HernandoBar2023Document322 pagesRemedial Law Case Digests - HernandoBar2023Robyn Summer Tamase ClaroNo ratings yet

- Rangwani Vs DinoDocument5 pagesRangwani Vs DinoEarnswell Pacina TanNo ratings yet

- SSC Circular No 2010-004 (IRR of RA 9903)Document4 pagesSSC Circular No 2010-004 (IRR of RA 9903)louis adriano baguioNo ratings yet

- University of San Agustin V CADocument10 pagesUniversity of San Agustin V CAPatNo ratings yet

- Crusaders Broadcasting System, Inc. vs. NationalDocument1 pageCrusaders Broadcasting System, Inc. vs. NationalDeniel Salvador B. Morillo100% (1)

- NLRC Lacks Jurisdiction Over Dismissal of Corporate Officer (Espino vs NLRC 1995Document1 pageNLRC Lacks Jurisdiction Over Dismissal of Corporate Officer (Espino vs NLRC 1995maanyag6685No ratings yet

- Francisco Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageFrancisco Vs Court of Appealslaw mabaylabayNo ratings yet

- Page 64 Sps. Javellana Vs Benito Legarda 59Document3 pagesPage 64 Sps. Javellana Vs Benito Legarda 59Nafiesa ImlaniNo ratings yet

- 1 PP v. Velasco 252 SCRA 135Document1 page1 PP v. Velasco 252 SCRA 135Abu Khaleel100% (1)

- CSC Upholds Dismissal of PCMC Worker for AWOLDocument8 pagesCSC Upholds Dismissal of PCMC Worker for AWOLHazel FernandezNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Can Directly Dismiss Errant Public Official for DishonestyDocument2 pagesOmbudsman Can Directly Dismiss Errant Public Official for Dishonestymisslee misseunNo ratings yet

- Garcia, Et Al. v. People - 318 SCRA 434Document5 pagesGarcia, Et Al. v. People - 318 SCRA 434Khenz MistalNo ratings yet

- Ac No. 10438Document2 pagesAc No. 10438Xiena Marie Ysit, J.DNo ratings yet

- Provos Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageProvos Vs Court of AppealsBenedick LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Andaya v. AbadiaDocument7 pagesAndaya v. Abadiaviva_33No ratings yet

- Estolas Vs Mabalot, 381 SCRA 702Document1 pageEstolas Vs Mabalot, 381 SCRA 702Leonard GarciaNo ratings yet

- POEA Ruling on Recruitment Agency's License Suspension AppealedDocument8 pagesPOEA Ruling on Recruitment Agency's License Suspension AppealedattyGezNo ratings yet

- Legaspi Vs City of CebuDocument16 pagesLegaspi Vs City of CebuCattleyaNo ratings yet

- Atty Suspended for Fraudulently Acquiring Client's SharesDocument1 pageAtty Suspended for Fraudulently Acquiring Client's Sharesmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- DANTE LIBAN vs. RICHARD GORDONDocument3 pagesDANTE LIBAN vs. RICHARD GORDONIyahNo ratings yet

- Philippine Numismatic V. Genesis AquinoDocument4 pagesPhilippine Numismatic V. Genesis AquinokeithnavaltaNo ratings yet

- Poe v. COMELEC - Dissent BrionDocument144 pagesPoe v. COMELEC - Dissent BrionJay Garcia100% (2)

- 11 Domingo Vs DBPDocument3 pages11 Domingo Vs DBPGoodyNo ratings yet

- Cultural Information On Conversation Topic Is PhilippinesDocument5 pagesCultural Information On Conversation Topic Is PhilippinesJoanna Felisa GoNo ratings yet

- Almonte v. VasquezDocument1 pageAlmonte v. VasquezRoxanne AvilaNo ratings yet

- En Banc (G.R. No. 209271, July 26, 2016) : Perlas-Bernabe, J.Document14 pagesEn Banc (G.R. No. 209271, July 26, 2016) : Perlas-Bernabe, J.Miguel AlagNo ratings yet

- COA Ruling on NPC Contract with Private LawyerDocument6 pagesCOA Ruling on NPC Contract with Private Lawyerenan_intonNo ratings yet

- Smart Communications, Inc. v. NTCDocument13 pagesSmart Communications, Inc. v. NTCHershey Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Maceda vs. Macaraig, 197 SCRA 771Document39 pagesMaceda vs. Macaraig, 197 SCRA 771Machida AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Spec. Pro. CasesDocument54 pagesConsolidated Spec. Pro. CasesLiz ZieNo ratings yet

- Gaoiran VS. Alcala, 444 SCRA 428 (2005)Document6 pagesGaoiran VS. Alcala, 444 SCRA 428 (2005)j0d3No ratings yet

- Cmo 54-1991Document8 pagesCmo 54-1991mick_15No ratings yet

- Revised Corporation Code of The PhilippinesDocument22 pagesRevised Corporation Code of The PhilippinesJillian Mitziko LimquecoNo ratings yet

- 338 MASANGYA Casela v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pages338 MASANGYA Casela v. Court of AppealsCarissa CruzNo ratings yet

- Part II - On Strikes and Lock OutsDocument53 pagesPart II - On Strikes and Lock OutsJenifer PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 80645 August 3, 1993: Mariano V. Ampl, Jr. For Petitioners. Ramon R. Buenaventura For Private-RespondentsDocument32 pagesG.R. No. 80645 August 3, 1993: Mariano V. Ampl, Jr. For Petitioners. Ramon R. Buenaventura For Private-RespondentsNicole Mae SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Binamira Vs GarruchoDocument1 pageBinamira Vs GarruchoJessamine OrioqueNo ratings yet

- People v. OngDocument16 pagesPeople v. OngLourdes LescanoNo ratings yet

- 011-Terminal Facilities & Services Corp v. PPA, 378 SCRA 82 PDFDocument18 pages011-Terminal Facilities & Services Corp v. PPA, 378 SCRA 82 PDFJopan SJNo ratings yet

- Admin DigestsDocument19 pagesAdmin DigestsYang D. F.No ratings yet

- RP LIBEL LAWSDocument5 pagesRP LIBEL LAWSBenedict-Karen BaydoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Document42 pagesCase Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Myrna Angay Obus100% (1)

- Producers Bank Not Required to Pay Bonus Differentials Due to Financial LossesDocument11 pagesProducers Bank Not Required to Pay Bonus Differentials Due to Financial LossesGayFleur Cabatit RamosNo ratings yet

- Cebu Portland Cement Co. v. Municipality ofDocument5 pagesCebu Portland Cement Co. v. Municipality ofDenise LabagnaoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 191336Document5 pagesG.R. No. 191336Philip Cesar EstreraNo ratings yet

- How To Write Case DigestDocument3 pagesHow To Write Case Digestvherny_corderoNo ratings yet

- Pimentel vs. Aguirre examines limits of presidential power over LGUsDocument2 pagesPimentel vs. Aguirre examines limits of presidential power over LGUsLIERANo ratings yet

- Atienza Vs Saluta PDFDocument19 pagesAtienza Vs Saluta PDFFritzNo ratings yet

- Ojt Appeal LetterDocument2 pagesOjt Appeal LetterT.j. Peñano100% (1)

- 24 Crisostomo v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pages24 Crisostomo v. Court of AppealsmimimilkteaNo ratings yet

- Pyro CopperDocument13 pagesPyro CopperoihahNo ratings yet

- Handicapped Workers Deemed Regular EmployeesDocument3 pagesHandicapped Workers Deemed Regular EmployeesCarlo FernandezNo ratings yet

- CME affirms election of Barangay CaptainDocument4 pagesCME affirms election of Barangay CaptainKay AvilesNo ratings yet

- Leslie Espino Vs NLRCDocument8 pagesLeslie Espino Vs NLRCMarvin MagaipoNo ratings yet

- PAL vs. ZamoraDocument16 pagesPAL vs. Zamoragoannamarie7814No ratings yet

- Creation, Establishment and Abolition of Administrative AgenciesDocument42 pagesCreation, Establishment and Abolition of Administrative AgenciesChristine Erno100% (1)

- Administrative Law 2 CasesDocument211 pagesAdministrative Law 2 Casesafro99No ratings yet

- Magallano Vs ErmitaDocument35 pagesMagallano Vs ErmitaEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Quimiguing Vs Icao DigestDocument1 pageQuimiguing Vs Icao DigestEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Lambino Vs Comelec Case Digest Shifts Philippine GovernmentDocument3 pagesLambino Vs Comelec Case Digest Shifts Philippine GovernmentEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Grand Asian Vs GalvesDocument29 pagesGrand Asian Vs GalvesEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Memory AidDocument56 pagesCriminal Procedure Memory AidRufino Gerard MorenoNo ratings yet

- Mentholatum vs. MangalimanDocument8 pagesMentholatum vs. MangalimanEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Chua Guan vs. Samahang MagsasakaDocument6 pagesChua Guan vs. Samahang MagsasakaEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds SEC decision annulling dissolution of Neugene Marketing IncDocument7 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court upholds SEC decision annulling dissolution of Neugene Marketing IncEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Sergio Naguiat vs. NLRCDocument15 pagesSergio Naguiat vs. NLRCEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Legal Forms 2009Document83 pagesLegal Forms 2009Enan IntonNo ratings yet

- Antam Consolidated V CADocument12 pagesAntam Consolidated V CAEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Mutual Inc. vs. Cebu StevedoringDocument6 pagesAtlantic Mutual Inc. vs. Cebu StevedoringEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Triplex Shoes v. Rice & Hutchins, Inc. Et Al. (Delaware, 1930)Document1 pageTriplex Shoes v. Rice & Hutchins, Inc. Et Al. (Delaware, 1930)Enan IntonNo ratings yet

- Escaño v. Filipinas Mining CorporationDocument4 pagesEscaño v. Filipinas Mining CorporationEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Rural Bank of Lipa City Vs CADocument9 pagesRural Bank of Lipa City Vs CAEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court RulingDocument20 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court RulingEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Bates v. DresserDocument4 pagesBates v. DresserEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Rural Bank of Lipa City Vs CA Case DigestDocument5 pagesRural Bank of Lipa City Vs CA Case DigestBerch Melendez100% (1)

- San Miguel Corporation Supreme Court Case Disputing Board ResolutionDocument11 pagesSan Miguel Corporation Supreme Court Case Disputing Board ResolutionEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Pascual Vs OrozcoDocument12 pagesPascual Vs OrozcoEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Motion to Reconsider RulingDocument5 pagesMotion to Reconsider RulingEnan Inton100% (1)

- Pantranco North ExpressDocument2 pagesPantranco North ExpressEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds non-binding nature of cement dealership agreementDocument10 pagesSupreme Court upholds non-binding nature of cement dealership agreementEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Government V Philippine SugarDocument8 pagesGovernment V Philippine Sugarherbs22221473No ratings yet

- Ramon Gonzales vs. PNBDocument6 pagesRamon Gonzales vs. PNBNivla YacadadNo ratings yet

- Majority Stockholders of Ruby Industrial V LimDocument43 pagesMajority Stockholders of Ruby Industrial V LimEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Ang-Abaya v. AngDocument7 pagesAng-Abaya v. AngEnan Inton100% (1)

- Premium Marble Resources Vs - CADocument5 pagesPremium Marble Resources Vs - CAEnan IntonNo ratings yet

- Complaint For Ejectment SampleDocument2 pagesComplaint For Ejectment SampleJoseph Denila LagunaNo ratings yet

- Digitalization and Acquisitions at HDFC BankDocument40 pagesDigitalization and Acquisitions at HDFC BankSambhavi SinghNo ratings yet

- Financial Management-230113 PDFDocument283 pagesFinancial Management-230113 PDFmaheswaran100% (1)

- Martel - Term PaperDocument10 pagesMartel - Term PaperGenalyn Española Gantalao DuranoNo ratings yet

- Mutual Funds Vs FD: Ms. Avanti DaradeDocument4 pagesMutual Funds Vs FD: Ms. Avanti DaradeAniket MuleNo ratings yet

- Depository Trust CompanyDocument11 pagesDepository Trust CompanyAntonio Luiz100% (6)

- Assignment Financial Market Regulations: Mdu-CpasDocument10 pagesAssignment Financial Market Regulations: Mdu-CpasTanuNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource WasDocument3 pagesThis Study Resource WasDeanne GuintoNo ratings yet

- BSE ExamDocument1 pageBSE ExamBhavin LapsiwalaNo ratings yet

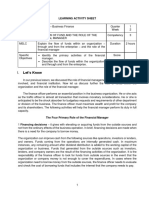

- Let's Know: Learning Activity SheetDocument8 pagesLet's Know: Learning Activity SheetWahidah BaraocorNo ratings yet

- UFCW LM-2 2011 Labor Organization Annual ReportDocument255 pagesUFCW LM-2 2011 Labor Organization Annual ReportUnion MonitorNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework of Treasury ManagementDocument146 pagesTheoretical Framework of Treasury ManagementPrithviraj Kumar100% (1)

- Adam Levitin and Tara Twomey White Paper On Mortgage ServicingDocument90 pagesAdam Levitin and Tara Twomey White Paper On Mortgage ServicingForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Project Report "Banking System" in India Introduction of BankingDocument15 pagesProject Report "Banking System" in India Introduction of BankingshabnammerajNo ratings yet

- KSCUBF Standing Advisory Committee AgendaDocument4 pagesKSCUBF Standing Advisory Committee AgendakscubfedNo ratings yet

- Solution IFS - B.com End Sem. Que. PaperDocument9 pagesSolution IFS - B.com End Sem. Que. Paperpranav2411No ratings yet

- Simplified SFM Theory Book by CA Jatin Nagpal - CompressedDocument47 pagesSimplified SFM Theory Book by CA Jatin Nagpal - CompressedSatyendraGuptaNo ratings yet

- Acuite Rating Sunshine HospitalDocument6 pagesAcuite Rating Sunshine Hospitalrahul.tibrewalNo ratings yet

- AB Bank's History and Products in 40 CharactersDocument16 pagesAB Bank's History and Products in 40 CharactersArefin RokonNo ratings yet

- Demat Account BenefitsDocument23 pagesDemat Account BenefitsPalwinder KaurNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship Report EdelweissDocument35 pagesSummer Internship Report EdelweissDushyant MudgalNo ratings yet

- Working Capital ManualDocument203 pagesWorking Capital ManualDeepika Pandey0% (1)

- Contrarian Investing - The Psychology of Going Against The CrowdDocument8 pagesContrarian Investing - The Psychology of Going Against The Crowdpjs15No ratings yet

- 1 Introduction To Capital MarketDocument41 pages1 Introduction To Capital MarketSrijan MajiNo ratings yet

- Brokerage Fees (Local & Foreign)Document3 pagesBrokerage Fees (Local & Foreign)Soraya AimanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Inflation AlchianDocument18 pagesEffects of Inflation AlchianCoco 12No ratings yet

- Cooperatives (Republic Act No. 9520 A.K.A. Philippine Cooperative Code of 2008)Document8 pagesCooperatives (Republic Act No. 9520 A.K.A. Philippine Cooperative Code of 2008)JAPNo ratings yet

- Dai24 Yuho EDocument293 pagesDai24 Yuho ERayhan AlfansaNo ratings yet

- Ketan Parekh Scam CaseDocument10 pagesKetan Parekh Scam CaseGavin Lobo100% (1)

- Advances Against Goods PDFDocument73 pagesAdvances Against Goods PDFVijay P PulavarthiNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy Statement: Bank of ZambiaDocument24 pagesMonetary Policy Statement: Bank of ZambiaCletus SikwandaNo ratings yet