Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Douglas Fogle-Cinema Is Dead

Uploaded by

doragreenissleepyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Douglas Fogle-Cinema Is Dead

Uploaded by

doragreenissleepyCopyright:

Available Formats

Cinema is Dead, Long Live the

Cinema

Celebrating 100 years of cinema

Art and film have a troubled and incestuous history. Orson Welles, for

example, may have attained auteur status with innovative and

revolutionary cinematic aesthetics while struggling within the

daunting constraints of the ollywood studio system. !ut while

Citi"en #ane $1%&1' is often cited as the most important film ever

made, Welles was punished for his transgressions during the editing

of his next feature (he )agnificent Ambersons $1%&*', which +#O re,

cut while he was away filming in -outh America. )ore recently, visual

artists li.e +obert /ongo and 0avid -alle have attempted to migrate

from the gallery into the multiplex, emerging from their garrets 1ust

long enough to savage the public with their touristic 1aunts into

commercial filmma.ing. !ut in many ways it2s Andy Warhol who

stands as the totemic mar.er between these two worlds. With his

eight hour film epic 3mpire $1%4&', a single, static shot of the 3mpire

-tate !uilding, Warhol brought the art world of 5ew 6or. crashing

into the bac.lots of ollywood, transforming the 7actory into a

dream factory. Warhol wanted to become a machine, and with his

purchase of a 14mm !olex movie camera in 1%48 he got his chance.

(he artist became a filmma.er.

With its fusion of cult pop auteurship, the ethos of experimental

filmma.ing, and a trenchant aesthetic minimalism, 3mpire is a fitting

establishing shot for the /os Angeles )useum of Contemporary Art2s

celebration of the centenary of cinema in its elaborate exhibition,

9all of )irrors: Art and 7ilm -ince 1%&;2. (he show is one of a spate

of li.e,minded attempts to explore the relationship between cinema

and the visual arts this past year. (he list includes the ayward

<allery2s 9-pellbound2 and 9100 =ahre #ino2 at the #unsthaus >?rich,

as well as single artist shows such as Chris )ar.er2s -ilent )ovie

$1%%&,;' and Chantal A.erman2s 023st $1%%;'. !ut 9all of )irrors2

has the special privilege of having been generated in the belly of the

beast itself. (hroughout the gallery Warhol, Weegee, Cindy -herman

and -alvador 0ali mingle with the li.es of itchcoc., Cronenberg,

<odard and Welles in a 1uxtaposition of the contemplative @uality of

static art with the dynamism of the moving image. !ut the

overarching conundrum that purportedly lin.s all of the filmma.ers

and artists in the exhibition is one of ontological proportions: 9what is

, or was , the cinemaA2

As unspecific as the art student2s perennial introductory @uery 9what

is artA2, the @uestion is, strangely enough, the best answered one in

the entire exhibition. !ecause what becomes abundantly clear $if

almost symptomatically' throughout all of these exhibitions is not so

much the hybridisation of film and the visual arts, but rather the

increasingly apparent gaps between media. 7ilmma.ers stumble

when attempting to manufacture static artB visual artists trip over

cinematic land,mines when crossing into film. !eyond this, the other

startling truth that comes to mind when loo.ing at these exhibitions

is how incredibly seductive film really is. When confronted by Welles2

Citi"en #ane, for example, iroshi -ugimoto2s blac. and white

photographs of empty movie theatres wither away li.e the witch in

the Wi"ard of O" $1%8%'. 3ven in Warhol2s wor., the 7actory screen

tests of 3die -edgwic. and <erard )alanga radiate a decidedly

different .ind of fascination from the sil.,screen paintings of )arilyn,

)arlon, /i" or (roy. (he reasons for this are impossible to pin down,

but the fact remains that the world has roc.ed to a rhythm of *&

frames per second for over a century and hasn2t loo.ed bac..

0oes this explain the recent proliferation of moving images in the

gallery spaceA /et2s face it, the relationship of film to visual art is not

a new phenomenon. (he two cultural spheres have been intimately

imbricated at least since the early *0s when the chiaroscuro

techni@ues of )ax +einhardt2s expressionist theatre found their way

into the repertoire of 7.W. )urnau, 7rit" /ang and other Weimar

filmma.ers. Add a dose of fascist persecution to the mixture and you

get the mass emigration to ollywood that resulted in the birth of

film noir, that hybrid child of <ermanic angst and American pulp

fiction. What2s new in the current artistic climate is something @uite

different: an institutional desire to frame films as ob1ets d2art. Cn part

this has been inspired by the increasing importance that the medium

of film has come to play in the wor. of contemporary artists:

practitioners as diverse as -igmar Dol.e, -tan 0ouglas and )atthew

!arney employ the moving image as a primary means of conveying

their message. Cn a world where artists coexist with screen stars and

pop music icons in the pages of Cnterview, Eogue and +olling -tone,

film provides a sexy street,cred to the visual artist, while the gallery

space offers a culturally edifying aura to the resumF of the

commercial filmma.er.

!ut all is not what it seems in the land of special effects and 1ump

cuts, and concretising the cinematic within the gallery space is not

always static,free. (his is amply illustrated in 9-pellbound2 which

resonates with the furious sounds of the box office as much as art

chatter. (erry <illiam2s installation for his film (welve )on.eys

$1%%;', for example , a wall of filing cabinets placed in front of a bac.

pro1ection of the film , serves as nothing less than an enormous piece

of mar.eting. +egardless of what one thin.s of the film $or of its far

more provocative progenitor /a =etFe $1%4*' by Chris )ar.er',

<illiam2s attempt at forging (welve )on.eys into a gallery

installation failed miserably, and its booming soundtrac. added

insult to in1ury by bleeding !ruce Willis2 voice into the surrounding

gallery space. !ut we can at least be than.ful that <illiam2s

contribution to 9-pellbound2 was only offensive in a commercial sort

of way. Deter <reenaway, on the other hand, saw fit to drag the

spectator into the recesses of his own maniacal ego in an installation

which attempted to rival the complex mise,en,scGnes of his films: live

actors in glass vitrinesB a cacophonous musical scoreB an epilepsy,

inducing light showB and an empty wall of chairs labelled

9AH0C35C32. Derhaps Clement <reenberg was right after all when he

suggested that each art form should find its own "ero degree.

!y contrast, the crossover pro1ects of filmma.ers such as Chris

)ar.er in his -ilent )ovie $commissioned by the Wexner Center for

the arts, and included in 9all of )irrors2' and Chantal A.erman in

the film and video installation of her feature 023st succeed in this tas.

of translation by stic.ing closer to their shooting scripts, so to spea..

!oth these wor.s insist on the cinematic, refusing to compromise the

fundamental precepts of filmic experience $montage, movement in

time, mise,en,scGne' to the constraints imposed by the gallery space,

yet both do so by relying on other technologies. )ar.er overcomes

these limitations by employing video and computer technology, while

A.erman actually pro1ects 023st as a film in the gallery along with an

installation which deconstructs the film into its constituent trac.ing

shots through 3astern 3urope on a ban. of video monitors. Cronically

perhaps, the one wor. in 9-pellbound2 that actually answers the

ontological @uestion of cinema as posed by )oCA2s 9all of )irrors2,

and holds its ground with )ar.er and A.erman, is 0ouglas <ordon2s

*& our Dsycho $1%%*', a video installation which pro1ects

itchcoc.2s film at three frames per second, free"ing the cinematic

grammar of this @uintessential example of auteurism in a gelatinous

petri dish of filmic deconstruction.

!ut even in these best,case scenarios, should we so readily applaud

the blurring of boundaries between the artist2s studio and the film

studioA (he Ctalian 7uturist )arinetti once called the museum a

sepulchre and an ossuary for dead art. (he worst cases of this

crossover phenomenon conform to this model by deploying a blatant

nostalgia for a culture of film , both commercial and experimental ,

that may no longer exist. Ct2s this @uestion of the potential death of

cinema as an art form that underlies all these exhibitions and which is

foregrounded in )oCA2s @uestion 9what is , or was , the cinemaA2 As a

spectator, however, the case is clear. Cn a cultural climate where filmic

debacles of epic proportions such as Waterworld $1%%;' and

Cut(hroat Csland $1%%;' wea.en the cinematic gene pool by radiating

their over,budget isotopes, films li.e Andy Warhol2s 3mpire still offer

a necessary corrective shoc. therapy. (he cinema is dead, long live

the cinema.

Douglas Fogle

About this article

Dublished on 04I0%I%4!y Douglas Fogle

You might also like

- Modified Surrealism EssayDocument17 pagesModified Surrealism EssayGeraldo MartinsNo ratings yet

- Invisible by Design: Reclaiming Art Nouveau For The CinemaDocument16 pagesInvisible by Design: Reclaiming Art Nouveau For The CinemaDanielle DifanteNo ratings yet

- Film and Theatre - SontagDocument15 pagesFilm and Theatre - SontagJesse LongmanNo ratings yet

- 1709 2037 1 PBDocument16 pages1709 2037 1 PBAndreea DalimonNo ratings yet

- Art Cinema PracticeDocument10 pagesArt Cinema PracticereneepiesNo ratings yet

- Notes of A Film Director by Sergei EisensteinDocument276 pagesNotes of A Film Director by Sergei EisensteinPratyansha100% (1)

- Indiana University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film HistoryDocument5 pagesIndiana University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film HistoryCorcaci April-DianaNo ratings yet

- Brecht, Bertolt - Brecht On Theatre. Extractos PDFDocument17 pagesBrecht, Bertolt - Brecht On Theatre. Extractos PDFreinaldilloNo ratings yet

- Secrets of Scene Painting and Stage EffectsDocument100 pagesSecrets of Scene Painting and Stage EffectsJo SanburgNo ratings yet

- Balsom, Screening Rooms PDFDocument16 pagesBalsom, Screening Rooms PDFfluffy_cushionNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF Theater and Film A Comparative Anthology PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF Theater and Film A Comparative Anthology PDFjames.lindon669100% (35)

- Chapter 15 The Postmodern FilmDocument9 pagesChapter 15 The Postmodern FilmGauravKumarNo ratings yet

- Brecht On Theatre 90Document17 pagesBrecht On Theatre 90hhNo ratings yet

- Of Another Cinema by Raymond BellourDocument17 pagesOf Another Cinema by Raymond BellourMax ElskampNo ratings yet

- The Art of CinemaDocument12 pagesThe Art of CinemaMarta FialhoNo ratings yet

- Arts and EntertainmentDocument11 pagesArts and EntertainmentLinh PhạmNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Modernism and TheatreDocument10 pagesChapter 11 Modernism and TheatreGauravKumar100% (1)

- Ruin, Archive and The Time of Cinema: Peter Delpeut's Lyrical NitrateDocument21 pagesRuin, Archive and The Time of Cinema: Peter Delpeut's Lyrical NitrateAnonymous y9IQflUOTmNo ratings yet

- The History of Movie Photography PDFDocument184 pagesThe History of Movie Photography PDFBlagovestNo ratings yet

- The Cinematic in Expanded Fields at The 54 Venice Biennale Justine GraceDocument13 pagesThe Cinematic in Expanded Fields at The 54 Venice Biennale Justine GracePatricio ArteroNo ratings yet

- On Jean-Luc Godard's Nouvelle Vague (1990)Document22 pagesOn Jean-Luc Godard's Nouvelle Vague (1990)Akif ErgulecNo ratings yet

- Film and Theatre-SontagDocument15 pagesFilm and Theatre-SontagJosé Miguel Palacios100% (1)

- Cluj Connection - Haunch of Venison, Valerie Knoll, Artforum, Aprilie 2007Document3 pagesCluj Connection - Haunch of Venison, Valerie Knoll, Artforum, Aprilie 2007Matei SamihaianNo ratings yet

- From Event To Extreme Reality The AestheDocument34 pagesFrom Event To Extreme Reality The AestheAnonymous uwoXOvNo ratings yet

- Gnosis and Iconoclasm - A Case Study of CinephiliaDocument17 pagesGnosis and Iconoclasm - A Case Study of CinephiliaManoel FriquesNo ratings yet

- 4 - Stage and ScreenDocument53 pages4 - Stage and ScreenMadalina HotoranNo ratings yet

- Hans Richter - The Film As An Original Art Form (1951)Document6 pagesHans Richter - The Film As An Original Art Form (1951)Tiko MamedovaNo ratings yet

- Haptical CinemaDocument30 pagesHaptical CinemagreggflaxmanNo ratings yet

- The Museum and The Moving Image: A Marriage Made at The Documenta?Document14 pagesThe Museum and The Moving Image: A Marriage Made at The Documenta?Lorena TravassosNo ratings yet

- Moving Lips - Cinema As VentriloquismDocument14 pagesMoving Lips - Cinema As VentriloquismArmando Carrieri100% (1)

- Fowler, Catherine - Room For Experiment. Gallery Films and Vertical Time From Maya Deren To Eija Liisa AhtilaDocument20 pagesFowler, Catherine - Room For Experiment. Gallery Films and Vertical Time From Maya Deren To Eija Liisa AhtilaDaniel Tercer MundoNo ratings yet

- Spellbound PDFDocument3 pagesSpellbound PDFLarisa OanceaNo ratings yet

- John Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Document312 pagesJohn Belton - Widescreen Cinema-Harvard University Press (1992)Andreea Cristina BortunNo ratings yet

- Donald Crafton, Emile Cohl, Caricature and FilmDocument2 pagesDonald Crafton, Emile Cohl, Caricature and Filmelsaesser.thomas2162No ratings yet

- Of Cypresses and SunflowersDocument7 pagesOf Cypresses and SunflowersJOHN A WALKERNo ratings yet

- The Allusive Eye. Illusion, Anti-Illusion, Allusion Peter Weibel Center For Art and Media (ZKM) in KarlsruheDocument4 pagesThe Allusive Eye. Illusion, Anti-Illusion, Allusion Peter Weibel Center For Art and Media (ZKM) in KarlsruhePreng LeshiNo ratings yet

- ArgosDocument4 pagesArgosJoseluisLPNo ratings yet

- Elsaesser Thomas - The Loop of Belatedness. Cinema After Film in The Contemporary Art Gallery PDFDocument19 pagesElsaesser Thomas - The Loop of Belatedness. Cinema After Film in The Contemporary Art Gallery PDFJojoNo ratings yet

- PARENTE, André - Cinema de Vanguarda Experimental e DispositivoDocument22 pagesPARENTE, André - Cinema de Vanguarda Experimental e DispositivoBeatriz Nunes100% (1)

- A Century of Cinema - Susan SontagDocument4 pagesA Century of Cinema - Susan Sontagcrisie100% (2)

- Magic and Illusion in Early Cinema by Dan North-LibreDocument12 pagesMagic and Illusion in Early Cinema by Dan North-LibreBogdan PetrovanNo ratings yet

- Carlson - Non-Traditional Theatre Space PDFDocument12 pagesCarlson - Non-Traditional Theatre Space PDFMarold Langer-PhilippsenNo ratings yet

- Film and Theatre (Susan Sontag)Document15 pagesFilm and Theatre (Susan Sontag)isabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- Santiago Alvarez DVD ReviewDocument2 pagesSantiago Alvarez DVD ReviewgnatwareNo ratings yet

- Exam 1 Name: Course: Date:: Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925)Document8 pagesExam 1 Name: Course: Date:: Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925)Writing OnlineNo ratings yet

- Brecht - Epic TheaterDocument17 pagesBrecht - Epic TheaterChristine EnsomoNo ratings yet

- Serial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and The Mass-Culture Genealogy of SurrealismDocument11 pagesSerial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and The Mass-Culture Genealogy of SurrealismhuythientranNo ratings yet

- Andre Bazin-The Technique of Citizen KaneDocument9 pagesAndre Bazin-The Technique of Citizen KanepaqsoriNo ratings yet

- An Uncomfortably Small, and Shrinking, World: Marina Zurkow Montclair Art MuseumDocument2 pagesAn Uncomfortably Small, and Shrinking, World: Marina Zurkow Montclair Art MuseumPao CamposNo ratings yet

- Bordwell, David. "The Musical Analogy"Document16 pagesBordwell, David. "The Musical Analogy"Mario PMNo ratings yet

- Non Traditional Theatre SpaceDocument12 pagesNon Traditional Theatre SpaceRogerio Marcondes MachadoNo ratings yet

- Arnheim, Rudolf - Art Today and The FilmDocument8 pagesArnheim, Rudolf - Art Today and The FilmlautxapNo ratings yet

- Brief Introduction of History of CinemaDocument43 pagesBrief Introduction of History of CinemacandrijanaNo ratings yet

- A Century of CinemaDocument6 pagesA Century of CinemawernickemicaNo ratings yet

- Abstract Film and Beyond-Malcolm LeGriceDocument160 pagesAbstract Film and Beyond-Malcolm LeGriceSangue CorsárioNo ratings yet

- Da Compilação À CollageDocument11 pagesDa Compilação À Collagebutterfly2014No ratings yet

- Two Moments From The Post-MediumDocument9 pagesTwo Moments From The Post-MediumpipordnungNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Scenery: Canvas Flats Three-DimensionalDocument2 pagesContemporary Scenery: Canvas Flats Three-Dimensionalkapil malviyaNo ratings yet

- A Philosophy For Communism: Rethinking Althusser' by Panagiotis Sotiris Reviewed by Ian Leask - MarDocument1 pageA Philosophy For Communism: Rethinking Althusser' by Panagiotis Sotiris Reviewed by Ian Leask - MardoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Russian Typographic RevolutionDocument5 pagesRussian Typographic RevolutiondoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- On Feminism & "Feminism"Document5 pagesOn Feminism & "Feminism"doragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- KINO SLANG: Danièle Huillet at WorkDocument22 pagesKINO SLANG: Danièle Huillet at WorkdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Allied Forces Knew About Holocaust Two Years Before Discovery of Concentration Camps, Secret Documents Reveal - The IndependentDocument6 pagesAllied Forces Knew About Holocaust Two Years Before Discovery of Concentration Camps, Secret Documents Reveal - The IndependentdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Correspondence On The German Student Movement - FIELDDocument18 pagesCorrespondence On The German Student Movement - FIELDdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Etienne Balibar - From Althusserian Marxism To The Philosophies of Marx? Twenty Years AfterDocument18 pagesEtienne Balibar - From Althusserian Marxism To The Philosophies of Marx? Twenty Years AfterdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Activism, Art and Social PracticeDocument16 pagesActivism, Art and Social PracticedoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Joris IvensDocument22 pagesJoris IvensdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Techniques of The ObserverDocument15 pagesTechniques of The ObserverdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Landy On SterrittDocument16 pagesLandy On SterrittdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- On The Neoliberal StageDocument8 pagesOn The Neoliberal StagedoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- For Ever GodardDocument14 pagesFor Ever GodarddoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Writing The ScreenplayDocument6 pagesWriting The ScreenplaydoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Remembering History, Reconstructing Memory: The Films of Jean-Gabriel PériotDocument3 pagesRemembering History, Reconstructing Memory: The Films of Jean-Gabriel PériotdoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Bells 2011Document260 pagesBells 2011doragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Re-Reading Freud's 'On Female Sexuality'Document16 pagesRe-Reading Freud's 'On Female Sexuality'doragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- World Religion Chapter 3Document6 pagesWorld Religion Chapter 3Amabell Banzon100% (1)

- Paleography BibliographyDocument5 pagesPaleography BibliographyNabil RoufailNo ratings yet

- The Weeping WomenDocument5 pagesThe Weeping Womenapi-341946993No ratings yet

- How We Came To Live Here PDFDocument46 pagesHow We Came To Live Here PDFJ.B. BuiNo ratings yet

- End-Of-Course Test Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ADocument9 pagesEnd-Of-Course Test Grammar, Vocabulary, and Pronunciation ABoomerang Institute100% (2)

- 16IdiomsAnimals (CAE&CPE)Document9 pages16IdiomsAnimals (CAE&CPE)Denise MartinsNo ratings yet

- Musical Instruments of IndonesiaDocument3 pagesMusical Instruments of IndonesiaAimee HernandezNo ratings yet

- List of Contextualized Learning ResourcesDocument2 pagesList of Contextualized Learning ResourcesJahlel SarsozaNo ratings yet

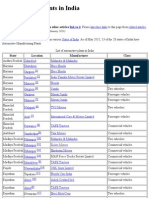

- List of Vehicle Plants in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesList of Vehicle Plants in India - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAjay Marya50% (2)

- Aisi Type p20 Mold Steel (Uns t51620)Document2 pagesAisi Type p20 Mold Steel (Uns t51620)doan anh TuanNo ratings yet

- Steinberger R Trem Maintenance Web PDFDocument1 pageSteinberger R Trem Maintenance Web PDFOscar Antonio HumanoNo ratings yet

- Falling Scales Chapter Two - SAS - CoDDocument39 pagesFalling Scales Chapter Two - SAS - CoDCWOD100% (1)

- Boris GroysDocument11 pagesBoris GroysJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- Dhikr and Prayers After The Tahajud SalahDocument5 pagesDhikr and Prayers After The Tahajud Salahselaras coidNo ratings yet

- Where Riches Is Everlastingly - WarlockDocument1 pageWhere Riches Is Everlastingly - WarlockPaulo RamosNo ratings yet

- Samuel Taylor ColeridgeDocument11 pagesSamuel Taylor Coleridgeshagun aggarwalNo ratings yet

- Types of Cameras PPPDocument19 pagesTypes of Cameras PPPLakan BugtaliNo ratings yet

- Flat SlabDocument11 pagesFlat SlabMasroor Ansari100% (2)

- Ceating Abundance Ram SutrasDocument1 pageCeating Abundance Ram SutrasAbhijeet DeshmukkhNo ratings yet

- Utility Spells by Type Mythos TomeDocument18 pagesUtility Spells by Type Mythos Tomedaemonprinceofchaos100% (1)

- Script 160927072300Document2 pagesScript 160927072300West NationNo ratings yet

- Drew Gasparini Sheet MusicDocument13 pagesDrew Gasparini Sheet MusicKate or KJ Carney90% (10)

- Calinawan Re - Ed.NOT DONEDocument5 pagesCalinawan Re - Ed.NOT DONERichard Jr CalinawanNo ratings yet

- Pre Colonial PeriodDocument13 pagesPre Colonial PeriodAngelica Dyan MendozaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia: Culture & History IiDocument87 pagesIslamic Arts Museum Malaysia: Culture & History IiSalahuddin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- JCR Vol. 08 No. 02: Symposium On The AtonementDocument245 pagesJCR Vol. 08 No. 02: Symposium On The AtonementChalcedon Foundation100% (2)

- Dricon Brochure July 2017 WebDocument17 pagesDricon Brochure July 2017 WebAndrew PiNo ratings yet

- The Generation of Postmemeory - Marianne HirschDocument26 pagesThe Generation of Postmemeory - Marianne Hirschmtustunn100% (2)

- Self-Laminating Labels For Laser Ink Jet Printers: Product BulletinDocument2 pagesSelf-Laminating Labels For Laser Ink Jet Printers: Product BulletinKATHERINENo ratings yet

- PTCH Class Multiplication in BoulezDocument26 pagesPTCH Class Multiplication in BoulezAndrés Moscoso100% (1)