Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cash Flow Ratio Analysis - Company Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

hartinahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cash Flow Ratio Analysis - Company Bankruptcy

Uploaded by

hartinahCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Article 28

Cash Flows, Ratio Analysis and the

W. T. Grant Company Bankruptcy

Although they surfaced as a gusher rather than a trickle, the problems that brought the

W. T. Grant Company into bankruptcy and, ultimately, liquidation, did not develop

overnight. Whereas traditional ratio analysis of Grants financial statements would not

have revealed the existence of many of the companys problems until 1970 or 1971,

careful analysis of the companys cash flows would have revealed impending doom as

much as a decade before the collapse.

Grants profitability, turnover and liquidity ratios had trended downward over the 10

years preceding bankruptcy. But the most striking characteristic of the company dur-

ing that decade was that it generated no cash internally. Although working capital pro-

vided by operations remained fairly stable through 1973, this figure (which constitutes

net income plus depreciation and is frequently referred to in the financial press as

cash flow) can be a very poor indicator of a companys ability to generate cash.

Through 1973, the W. T. Grant Companys operations were a net user, rather than pro-

vider, of cash.

Grants continuing inability to generate cash from operations should have provided in-

vestors with an early signal of problems. Yet, as recently as 1973, Grant stock was sell-

ing at nearly 20 times earnings. Investors placed a much higher value on Grants

prospects than an analysis of the companys cash flow from operations would have

warranted.

James A. Largay, III and Clyde P. Stickney

The W. T. Grant Company was the nations largest re-

tailer when it filed for protection of the Court under chap-

ter XI of the National Bankruptcy Act on October 2, 1975.

Only four months later, the creditors committee voted

for liquidation, and Grant ceased to exist. The collapse of

Grant is a business policy professors dreamambiguous

marketing strategy, personnel compensation based on

questionable incentive schemes, financially and adminis-

tratively unsound credit operations, centralization versus

decentralization issues and poorly conceived and poorly

executed long-range plans. Problems of this magnitude

do not develop overnight, although they often surface as

a gusher rather than a trickle.

As we will show, a traditional ratio analysis of Grants

financial statements would not have suggested the exist-

ence of many of these problems until approximately 1970

or 1971. As recently as 1973, Grant stock was selling at

nearly 20 times earnings. Perhaps investors believed that

Grant would continue to prosper despite many years of

consistent but lackluster performance; after all, the com-

pany had been in existence since the turn of the century,

paying dividends regularly from 1906 until August 27,

1974. But Grants demise should not have come as a sur-

prise to anyone following its fortunes closely; a careful

analysis of the companys cash flows would have re-

vealed the impending problems as much as a decade be-

fore the collapse.

Stock Prices and Ratio Analysis

Prior to 1971, Grants stock had tended to perform like

other variety store chain stocks. Beginning in June or July

of 1971, however, the stock price performance of Grant

and the other variety chains parted ways.

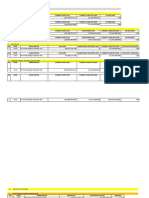

Exhibit I presents data on monthly closing prices and

various ratios from Grants financial statements for the 10

years preceding bankruptcy in 1975. The top panel shows

the December 31 closing price for Grants stock for each

year expressed as a ratio of the closing price on December

31, 1964 (i.e., the December 31, 1964 closing price equals

100). It also shows the values of the Standard & Poors Va-

riety Chain Stock Price Index and the Standard & Poors

ANNUAL EDITIONS

2

Article 28. Cash Flows, Ratio Analysis and the W. T. Grant Company Bankruptcy

3

500 Composite Stock Price Index at the end of each year,

each expressed as a ratio of its value on December 31,

1964.

The bottom four panels in Exhibit I shows the trends in

Grants profitability, turnover, liquidity and solvency ra-

tios over the fiscal periods between 1966 and 1975 (ending

January 31 of each year). The profitability, turnover and

liquidity ratios tended downward over this 10-year pe-

riod. The solvency ratios reflect increasing proportions of

liabilities in the capital structure. The most significant de-

terioration in these ratios, however, occurred during the

1970 and 1971 fiscal periods, leading the stock markets

recognition of Grants problems by approximately one

year.

Net Income and Cash Flows

The most striking characteristic of the Grant Company

during the decade before its bankruptcy was that it gen-

erated virtually no cash internally. The company simply

lost its ability to derive cash from operations. After ex-

hausting the possibilities of its liquid resources, it had to

tap external markets for funds. As the failure to generate

cash internally continued, the need for external financing

snowballed.

Most textbooks in corporate finance, investments and

financial statements analysis devote little attention to

computing or using cash flow from operations. Yet the

calculations are straightforward enough. One starts with

working capital provided by operations from the state-

ment of changes in financial position, adds changes in

current asset accounts (other than cash) that decreased

and current liability accounts that increased and subtracts

changes in current asset accounts (other than cash) that

increased and current liability accounts that decreased. In

accounting terms, the calculation is equivalent to adding

credit changes in working capital accounts and subtract-

ing debit changes. Exhibit II summarizes the process of

converting working capital provided by operations to

cash flow provided by operations.

Exhibit III graphs Grants net income, working capital

provided by operations and cash flow provided by oper-

ations for the 1966 to 1975 fiscal periods. Note how poorly

working capital provided by operations correlates with

cash flow from operations. The financial press frequently

refers to cash flow, defined as net income plus depreci-

ation. This measure of cash flow approximates working

capital provided by operations, which (as Exhibit III

shows) may prove a very poor surrogate for the cash flow

actually generated by operations.

While Grants net income was relatively steady

through the 1973 period, operations were a net user

rather than provider, of cash in all but two years (1968

and 1969). Even in these two years, operations provided

only insignificant amounts of cash. Grants continuing in-

ability to generate cash from operations should have pro-

vided investors with an early signal of problems.

Was the Market for Grant Stock Efficient?

In an efficient market, stock prices continually reflect all

publicly available information about a companys past

performance and future prospects. The evidence pre-

sented here, however, seems to suggest that W. T. Grant

Company was a counterexample to market efficiency.

Operations were a net user of cash in eight of Grants

last 10 years. Between January 31, 1966 and January 31,

1973, Grants sales nearly doubled, but its earnings and

ANNUAL EDITIONS

4

earnings per share remained virtually unchanged. De-

spite its failure to translate vastly increased sales into ad-

ditional profits, Grants price-earnings ratio on January

31, 1973 was about twice what it had been on January 31,

1966.

We compared Grants price-earnings ratios with those

of similar variety chains (Kresge, McCrory, Murphy and

Woolworth) over the 196575 period. Until 1973, Grants

price-earnings multiple tended to exceed the multiples of

the other variety chains, with the exception of Kresge.

Traders in Grant stock during the companys last decade

placed a much higher value on Grants prospects than an

analysis of the companys cash flow from operations

would have warranted.

James Largay is Professor of Accounting at the college of Business and Econom-

ics, Lehigh University. This article was written while he was Coopers & Ly-

brand Visiting Associate Professor of Accounting at The Amos Tuck School of

Business Administration, Dartmouth College. Clyde Stickney is Associate Pro-

fessor of Accounting at The Amos Tuck School of Business Administration,

Darthmouth College.

The authors thank the Tuck Associates Program for its financial support.

From Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1980, pp. 51-54. 1980 by the Financial Analysts Journal. Reprinted by permission.

You might also like

- Like The WayDocument30 pagesLike The WayAtif AzharNo ratings yet

- Davis Fund Fall 2013Document10 pagesDavis Fund Fall 2013William ChiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17Document48 pagesChapter 17Shiv NarayanNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Ch17Document54 pagesFinancial Accounting Ch17Diana FuNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 178.244.206.198 On Thu, 25 Mar 2021 12:03:28 UTCDocument41 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 178.244.206.198 On Thu, 25 Mar 2021 12:03:28 UTCElif AcarNo ratings yet

- Christopher C. Davis and Kenneth C. Feinberg Portfolio ManagersDocument11 pagesChristopher C. Davis and Kenneth C. Feinberg Portfolio ManagersfwallstreetNo ratings yet

- X-Factor 102211 - Market Is Not CheapDocument11 pagesX-Factor 102211 - Market Is Not CheapmathewmiypeNo ratings yet

- Disgorge The Cash: The Disconnect Between Corporate Borrowing and InvestmentDocument38 pagesDisgorge The Cash: The Disconnect Between Corporate Borrowing and InvestmentRoosevelt Institute100% (1)

- Graham Et Al - 2015Document26 pagesGraham Et Al - 2015Adam JohnosonNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of US StandardsDocument12 pagesThe Evolution of US StandardsZeeshanSameenNo ratings yet

- DKAM ROE Reporter April 2020Document8 pagesDKAM ROE Reporter April 2020Ganesh GuhadosNo ratings yet

- Mason Hawkins 11q3letterDocument4 pagesMason Hawkins 11q3letterrodrigoescobarn142No ratings yet

- 8 Markets MythsDocument18 pages8 Markets MythsVicente Manuel Angulo GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- 3.9 Earning's Management and The Long-Run Market Performance of Initial Public OfferingDocument35 pages3.9 Earning's Management and The Long-Run Market Performance of Initial Public Offeringمحمد ابوشريفNo ratings yet

- Hoffman C Financial Analysis The GapDocument22 pagesHoffman C Financial Analysis The GapHenizionNo ratings yet

- McKinsey Global Institute - Define Contributions MarketDocument37 pagesMcKinsey Global Institute - Define Contributions MarketHugh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Investment Commentary: Market and Performance SummaryDocument12 pagesInvestment Commentary: Market and Performance SummaryCanadianValue100% (1)

- SSRN Id3657612Document20 pagesSSRN Id3657612Cedric ZhouNo ratings yet

- Binder 1Document4 pagesBinder 1Sheetanshu TripathiNo ratings yet

- Trade Report February 09Document7 pagesTrade Report February 09David DorrNo ratings yet

- Does Dividend Policy Foretell Earnings Growth?: Draft: December 2001 Comments WelcomeDocument34 pagesDoes Dividend Policy Foretell Earnings Growth?: Draft: December 2001 Comments WelcomeSnehanshu BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Broyhill Letter (Q2-08)Document3 pagesBroyhill Letter (Q2-08)Broyhill Asset ManagementNo ratings yet

- Weitz Funds 4 Q2008 LetterDocument5 pagesWeitz Funds 4 Q2008 LetterfwallstreetNo ratings yet

- Gryphon 2015 OutlookupdateDocument10 pagesGryphon 2015 Outlookupdateapi-314576946No ratings yet

- Berkshire Hathaway Letter 1972Document4 pagesBerkshire Hathaway Letter 1972jinwei fuNo ratings yet

- Third Point Q4 Investor Letter FinalDocument12 pagesThird Point Q4 Investor Letter FinalZerohedge100% (3)

- Puzzle of The Cash Flow StatementDocument8 pagesPuzzle of The Cash Flow Statementqwertycvc0% (1)

- Chapter 3 - Financial AnalysisDocument39 pagesChapter 3 - Financial AnalysisHeatstroke0% (1)

- Big Lots IncDocument99 pagesBig Lots IncWeber HsuNo ratings yet

- Statistical Arbitrage 6Document7 pagesStatistical Arbitrage 6TraderCat SolarisNo ratings yet

- Valuation Thesis: Target Corp.: Corporate Finance IIDocument22 pagesValuation Thesis: Target Corp.: Corporate Finance IIagusNo ratings yet

- Balance of PaymentsDocument21 pagesBalance of PaymentsKiran Kumar KuppaNo ratings yet

- Gruber Corporate Profits and SavingDocument60 pagesGruber Corporate Profits and SavingeconstudentNo ratings yet

- Summer 2013Document2 pagesSummer 2013gradnvNo ratings yet

- Third Point Q2 15Document10 pagesThird Point Q2 15marketfolly.comNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Outline and Guideline UpdateDocument4 pagesAssignment 1 Outline and Guideline UpdateĐan Nguyễn PhươngNo ratings yet

- CH 18Document40 pagesCH 18Louina YnciertoNo ratings yet

- Shareholder First Ñ Reason For US Economic Disaster: Hese Days Rather ThanDocument16 pagesShareholder First Ñ Reason For US Economic Disaster: Hese Days Rather ThanSheshadev PradhanNo ratings yet

- Iconix Note 20151229 PDFDocument10 pagesIconix Note 20151229 PDFmoonflye82220% (1)

- A Top Down Look at The Chinese Equity MarketDocument8 pagesA Top Down Look at The Chinese Equity Marketgo joNo ratings yet

- Wally Weitz Letter To ShareholdersDocument2 pagesWally Weitz Letter To ShareholdersAnonymous j5tXg7onNo ratings yet

- The End of Buy and Hold ... and Hope Brian ReznyDocument16 pagesThe End of Buy and Hold ... and Hope Brian ReznyAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Butler Lumber Final First DraftDocument12 pagesButler Lumber Final First DraftAdit Swarup100% (2)

- Pitchbook & Grant Thornton: Private Equity Exits Report 2011 Mid-Year EditionDocument18 pagesPitchbook & Grant Thornton: Private Equity Exits Report 2011 Mid-Year EditionYA2301No ratings yet

- The Challenge of Bank Restructuring in ChinaDocument12 pagesThe Challenge of Bank Restructuring in ChinaMarianinaTrandafirNo ratings yet

- Statements of Cash Flows Three ExamplesDocument7 pagesStatements of Cash Flows Three Examplesmohamed arbi taifNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 - Financial Statement Analysis - Financial Accounting - IFRS, 3rd EditionDocument64 pagesChapter 14 - Financial Statement Analysis - Financial Accounting - IFRS, 3rd EditionMuhammad Rahman RidwanNo ratings yet

- Topic: Financial Statements and Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument26 pagesTopic: Financial Statements and Financial Ratio AnalysisSobanah ChandranNo ratings yet

- Outlook For 2013: A Changing Playbook: InsightsDocument28 pagesOutlook For 2013: A Changing Playbook: InsightssukeerrNo ratings yet

- Intermediat e AccountingDocument127 pagesIntermediat e AccountingMegz OkadaNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - Case 1.5Document7 pagesGroup 1 - Case 1.5lumiradut70100% (2)

- Funds Analysis, Cash-Flow Analysis, and Financial PlanningDocument31 pagesFunds Analysis, Cash-Flow Analysis, and Financial Planningmyasir1992100% (1)

- 2019 Investment OutlookDocument22 pages2019 Investment OutlookAnonymous HsoXPyNo ratings yet

- Investing For A New World: Managing Through Low Yields and High VolatilityDocument16 pagesInvesting For A New World: Managing Through Low Yields and High VolatilityPenna111No ratings yet

- Ulman Financial Fourth Quarter Newsletter - 2018-10Document8 pagesUlman Financial Fourth Quarter Newsletter - 2018-10Clay Ulman, CFP®No ratings yet

- Corporate Financial Distress, Restructuring, and Bankruptcy: Analyze Leveraged Finance, Distressed Debt, and BankruptcyFrom EverandCorporate Financial Distress, Restructuring, and Bankruptcy: Analyze Leveraged Finance, Distressed Debt, and BankruptcyNo ratings yet

- The What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsFrom EverandThe What, The Why, The How: Mergers and AcquisitionsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Dividend Imperative: How Dividends Can Narrow the Gap between Main Street and Wall StreetFrom EverandThe Dividend Imperative: How Dividends Can Narrow the Gap between Main Street and Wall StreetNo ratings yet

- The Tip of Indian Banking - Part 4Document424 pagesThe Tip of Indian Banking - Part 4ambujchinuNo ratings yet

- Rules Relating To The Terms of Employment and Working Conditions of The Employees of Primary Agricultural Credit Co-Operative Societies. (2001)Document12 pagesRules Relating To The Terms of Employment and Working Conditions of The Employees of Primary Agricultural Credit Co-Operative Societies. (2001)Dhineshkumar SNo ratings yet

- Shivani Corporate Finance 8thDocument15 pagesShivani Corporate Finance 8thShivani Singh ChandelNo ratings yet

- Working Capital ItcDocument73 pagesWorking Capital Itcntulani1100% (1)

- Ratio Analysis Pankaj 180000502015Document64 pagesRatio Analysis Pankaj 180000502015PankajNo ratings yet

- Financial RatiosDocument15 pagesFinancial RatiosKeith Joshua GabiasonNo ratings yet

- Review of Working Capital PDFDocument12 pagesReview of Working Capital PDFsandhyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 IntroductionDocument32 pagesChapter 1 IntroductionNowshad AyubNo ratings yet

- Cafm Paper 10 MCQDocument50 pagesCafm Paper 10 MCQDeep PatelNo ratings yet

- Unit II - CFDocument26 pagesUnit II - CFuser 02No ratings yet

- Operating Working Capital (INV+AR-AP)Document33 pagesOperating Working Capital (INV+AR-AP)Neethu Nair40% (5)

- Monte CarloDocument81 pagesMonte CarloRaj Kumar100% (1)

- Specific Accountancy Project: ComgyanDocument31 pagesSpecific Accountancy Project: ComgyanSavi MahajanNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Analysis HW5Document2 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis HW5mavi100% (1)

- FABM2 12 Q1 Mod5 Analysis-Of-Financial-Statements V5Document35 pagesFABM2 12 Q1 Mod5 Analysis-Of-Financial-Statements V5Janna GunioNo ratings yet

- Gitman Chapter 15 Working CapitalDocument67 pagesGitman Chapter 15 Working CapitalArif SharifNo ratings yet

- Cash Flows Statement - Two ExamplesDocument4 pagesCash Flows Statement - Two Examplesakash srivastavaNo ratings yet

- MGT 401Document6 pagesMGT 401Ali Akbar MalikNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Finance of Stone CrusherDocument34 pagesA Project Report On Finance of Stone Crusherjockernitu69% (16)

- Balance Sheet AnalysisDocument3 pagesBalance Sheet AnalysisNishant SinghNo ratings yet

- Pidilite Industries Management Accounting Ratio Analysis Project FileDocument180 pagesPidilite Industries Management Accounting Ratio Analysis Project FileAlok jha100% (4)

- Commercial Bank ManagementDocument8 pagesCommercial Bank ManagementShilpika ShettyNo ratings yet

- Pankaj Internship ProjectDocument26 pagesPankaj Internship ProjectPankajNo ratings yet

- "Working Capital Management": of "Metro Tyres"Document64 pages"Working Capital Management": of "Metro Tyres"Shubham bajajNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument53 pagesFinancial Statement Analysisremon4hrNo ratings yet

- Educ 209 Midterm Exam - Elaila Mae Z. BrionesDocument11 pagesEduc 209 Midterm Exam - Elaila Mae Z. BrionesJanine C. TagumNo ratings yet

- Determination of Working Capital RequirementDocument18 pagesDetermination of Working Capital RequirementGaganGabriel0% (1)

- EdgeReport TATAELXSI CaseStudy 10 04 2023 417Document34 pagesEdgeReport TATAELXSI CaseStudy 10 04 2023 417Department of power MIS CellNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management of Axis Bank "": Mangalmay Institute of Management and Technology Greater NoidaDocument109 pagesWorking Capital Management of Axis Bank "": Mangalmay Institute of Management and Technology Greater NoidaAbhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Tugas Rasio WilmarDocument7 pagesTugas Rasio WilmarMuslim HabibieNo ratings yet