Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transient Ischemic Attacks: Part I. Diagnosis and Evaluation

Uploaded by

Andi Saputra0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views10 pagesA TIA presents as a syndrome rather than any one sign or symptom. There is no reliable way to determine if the abrupt onset of neurologic deficits represents reversible ischemia without subsequent brain damage. Transient ischemic attack is no longer considered a benign event but a critical harbinger of impending stroke.

Original Description:

Original Title

p1665

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA TIA presents as a syndrome rather than any one sign or symptom. There is no reliable way to determine if the abrupt onset of neurologic deficits represents reversible ischemia without subsequent brain damage. Transient ischemic attack is no longer considered a benign event but a critical harbinger of impending stroke.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views10 pagesTransient Ischemic Attacks: Part I. Diagnosis and Evaluation

Uploaded by

Andi SaputraA TIA presents as a syndrome rather than any one sign or symptom. There is no reliable way to determine if the abrupt onset of neurologic deficits represents reversible ischemia without subsequent brain damage. Transient ischemic attack is no longer considered a benign event but a critical harbinger of impending stroke.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 10

than 50 percent of all adverse events

occurred within the first four days after

the TIA. Notably, of the patients with TIA

who returned to the emergency depart-

ment with stroke (10.5 percent), approxi-

mately one half had the stroke within

the first 48 hours after the initial TIA. In

2.6 percent of patients with TIA, hospi-

talization was required for cardiac events,

including congestive heart failure, unsta-

ble angina, cardiac arrest, and ventricular

arrhythmia.

Clinical Presentation

The more common clinical presenta-

tions of TIA are described in Table 1. In

general, a TIA presents as a syndrome

rather than any one sign or symptom.

Pre-emergency Department Care

There is no reliable way to determine

if the abrupt onset of neurologic deficits

represents reversible ischemia without

subsequent brain damage or if ischemia

will result in permanent damage to the

brain (e.g., stroke). Therefore, all patients

B

ased on an increased under-

standing of brain ischemia

and the introduction of new

treatment options, a working

group has proposed rede-

fining transient ischemic attack (TIA) as

a brief episode of neurological dysfunc-

tion caused by focal brain or retinal isch-

emia, with clinical symptoms typically

lasting less than one hour, and without

evidence of acute infarction.

1(p1715)

This

definition underscores the urgency of rec-

ognizing TIA as an important warning of

impending stroke and facilitating rapid

evaluation and treatment of TIA to pre-

vent permanent brain ischemia.

Epidemiology

An estimated 200,000 to 500,000 TIAs

occur annually in the United States.

2

One study

2

found that 25 percent of

patients who presented to an emergency

department with TIA had adverse events

within 90 days; 10 percent of the events

were strokes, and the vast majority of

the strokes were fatal or disabling.

3

More

Transient ischemic attack is no longer considered a benign event but, rather, a critical

harbinger of impending stroke. Failure to quickly recognize and evaluate this warning

sign could mean missing an opportunity to prevent permanent disability or death. The

90-day risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack has been estimated to be approxi-

mately 10 percent, with one half of strokes occurring within the first two days of the

attack. The 90-day stroke risk is even higher when a transient ischemic attack results

from internal carotid artery stenosis. Most patients reporting symptoms of transient

ischemic attack should be sent to an emergency department. Patients who arrive at

the emergency department within 180 minutes of symptom onset should undergo an

expedited history and physical examination, as well as selected laboratory tests, to

determine if they are candidates for thrombolytic therapy. Initial testing should include

complete blood count with platelet count, prothrombin time, International Normalized

Ratio, partial thromboplastin time, and electrolyte and glucose levels. Computed tomo-

graphic scanning of the head should be performed immediately to ensure that there

is no evidence of brain hemorrhage or mass. A transient ischemic attack can be mis-

diagnosed as migraine, seizure, peripheral neuropathy, or anxiety. (Am Fam Physician

2004;69:1665-74,1679-80. Copyright 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Transient Ischemic Attacks:

Part I. Diagnosis and Evaluation

NINA J. SOLENSKI, M.D., University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville, Virginia

O A patient infor-

mation handout on

strokes and TIAs, writ-

ten by the author of

this article, is provided

on page 1679.

See page 1591 for defi-

nitions of strength-of-

recommendation labels.

COVER ARTICLE

This article

exemplifies the

AAFP 2004 Annual

Clinical Focus on caring

for Americas aging

population.

This is part I of a two-

part article on transient

ischemic attacks. Part

II, Treatment, will

appear in this issue on

page 1681.

Downloaded from the American Family Physician Web site at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncommercial

use of one individual user of the Web site. All other rights reserved. Contact copyrights@aafp.org for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

with symptoms of TIA should receive an

expedited evaluation.

Office staff should be trained to inform

the family physician immediately if a patient

calls or presents with symptoms that could

represent a TIA. Neurologic symptoms that

crescendo with increasing frequency, dura-

tion, or severity are particularly ominous signs

of impending stroke.

Most patients with possible TIA should be

sent immediately to the nearest emergency

department. If they have had symptoms

for fewer than 180 minutes, they should be

sent to an emergency department that offers

acute thrombolytic therapy. Patients should

not drive themselves to the hospital. To

speed evaluation, it is appropriate to activate

the 9-1-1 Emergency Medical Service system

for transport.

2,3

On presentation to the emergency depart-

ment, patients who have had symptoms for

fewer than 180 minutes might be candidates

1666-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 / APRIL 1, 2004

The proposed redefinition of transient ischemic attack is a

brief episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal

brain or retinal ischemia, with clinical symptoms typically

lasting less than one hour, and without evidence of acute

TABLE 1

Common Clinical Presentations of TIA

Affected area Signs and symptoms Implications

Cranial nerves Visual loss in one or both eyes Bilateral loss may indicate more ominous onset of brainstem

ischemia.

Double vision If double vision is subtle, the patient may describe it as

blurry vision.

Vestibular dysfunction True vertigo is likely to be described as a spinning sensation

rather than nonspecific lightheadedness.

Difficulty swallowing Trouble swallowing may indicate brainstem involvement; if the

swallowing problem is severe, there may be an increased risk

of aspiration.

Motor function Unilateral or bilateral weakness affecting Bilateral signs may indicate more ominous onset of brainstem

the face, arm, or leg ischemia.

Sensory function Unilateral or bilateral: either decreased If sensory dysfunction occurs without other signs or symptoms,

sensation (numbness) or increased the prognosis may be more benign, but recurrence is high.

sensation (tingling, pain) in the face,

arm, leg, or trunk

Speech and Slurring of words or reduced verbal output; If speech is severely slurred or facial drooling is excessive, there

language difficulty pronouncing, comprehending, is an increased risk of aspiration.

or finding words Writing and reading also may be impaired.

Coordination Clumsy arms, legs, or trunk; loss of balance Incoordination of limbs, trunk, or gait may indicate cerebellar

or falling (particularly to one side) with or brainstem ischemia.

standing or walking

Psychiatric or Apathy or inappropriate behavior These symptoms can indicate frontal lobe involvement and

cognitive frequently are misinterpreted as poor volitional cooperation.

function

Excessive somnolence This symptom may indicate bilateral hemispheric or brainstem

involvement.

Agitation or psychosis Rarely, these symptoms may indicate brainstem ischemia,

particularly if they occur in association with cranial nerve

or motor dysfunction.

Confusion or memory changes These rarely are isolated symptoms; more frequently, they are

associated with language, motor, sensory, or visual changes.

Inattention to surrounding environment, Depending on the severity of neglect, the physician may

particularly to one side; if severe, patient need to lift the patients arm to check for strength,

may deny deficit or even his or her own rather than rely on the patient to perform this task.

body parts.

TIA = transient ischemic attack.

for treatment with tissue-type plasminogen

activator (tPA).

4,5

If a patient is not a candi-

date for tPA treatment, antiplatelet therapy

should be initiated as soon as it can be deter-

mined that there are no contraindications.

4-6

[Reference 6: SOR A, rating of benefits]

Inpatient or Outpatient Evaluation

Guidelines issued by the National Stroke

Association

7

recommend evaluation within

hours of the onset of TIA symptoms, prefer-

ably in an emergency department. If appro-

priate imaging studies are not immediately

available in the emergency department or out-

patient setting, the patient should be hospital-

ized for observation.

7

[SOR C, expert opin-

ion] Relative indications for more extended

inpatient evaluation for TIA or stroke are

listed in Table 2.

Patients with symptoms of acute TIA for

fewer than 24 to 48 hours should undergo

diagnostic testing in the emergency depart-

ment.

8

[SOR C, expert opinion] Patients

whose symptoms have resolved for more than

48 hours should receive urgent inpatient or

outpatient evaluation.

Initial Work-Up for Suspected TIA

The first step in evaluating a patient with

symptoms of TIA is to confirm the diagnosis

(Figure 1).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The most common imitators of TIA are

glucose derangement, migraine, seizure, post-

ictal states, and tumors (especially with acute

hemorrhage).

TIA typically has a rapid onset, and maxi-

mal intensity usually is reached within min-

utes. Fleeting episodes lasting one or two sec-

onds or nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue,

lightheadedness (in the absence of other cer-

ebellar or brainstem symptoms), and bilateral

rhythmic shaking of the limbs are less likely

presentations of acute cerebral ischemia.

Distinguishing TIA from migraine aura

can be difficult. Younger age, previous his-

tory of migraine (with or without aura), and

associated headache, nausea, or photophobia

are more suggestive of migraine than TIA. In

general, migraine aura tends to have a march-

ing quality; for example, symptoms such as

tingling may progress from the fingers to

the forearm to the face. Migraine aura also is

APRIL 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-1667

Neurologic symptoms that crescendo with increasing fre-

quency, duration, or severity are particularly ominous signs of

impending stroke.

TABLE 2

Relative Indications for Inpatient Evaluation of Possible TIA or Stroke*

Condition Implications

High-risk cardioembolic source: acute myocardial infarction Consider anticoagulation.

(especially if large and significant wall-motion abnormality

is present), mural thrombi, new-onset atrial fibrillation

TIAs manifested by major symptoms such as dense paralysis Possible evolving large hemispheric stroke with increased risk of

or severe language disorder brain swelling

Increasing frequency or severity of TIAs (crescendo pattern) Possible evolving thromboembolic stroke

Evidence of high-grade carotid artery stenosis Carotid artery evaluation for possible emergency intervention (surgery,

stent, or angioplasty)

Drooling, imbalance, decreased alertness, difficulty Increased risk of falling, or of aspiration and other pulmonary

swallowing complications

Severe headache, photophobia, stiff neck, recent syncope Possible subarachnoid hemorrhage: obtain emergency computed

tomographic scan of the head; if the scan is negative but clinical

suspicion remains high, cerebrospinal fluid evaluation or possible

cerebral angiography is needed.

TIA = transient ischemic attack.

*May require more than 23 hours of observation in the emergency department, or hospitalization for observation.

more likely to have a more gradual onset and

resolution, with a longer duration of symp-

toms than in a typical TIA.

If a patient has explosive onset of a severe

headache, with or without photophobia, stiff

neck, or syncope, acute subarachnoid hemor-

rhage is a possibility. Rarely, TIA is mistaken

for the first presentation of multiple sclerosis

in young patients or for amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis in older patients.

HISTORY

A general medical history should be

obtained in all patients with suspected TIA.

Special emphasis should be given to pos-

sible symptoms of TIA (Table 1), and stroke

risk factors should be identified to determine

the likelihood that the symptoms are caused

by TIA. Modifiable risk factors for stroke

include hypertension, diabetes, cardiac dis-

ease, elevated blood lipid levels, carotid artery

stenosis, smoking, sickle cell anemia, excessive

alcohol use, obesity, and physical inactivity.

7

Whether hypercholesterolemia is an inde-

pendent primary risk factor for stroke remains

uncertain.

9

However, hypercholesterolemia is

a significant risk factor for coronary heart dis-

ease (CHD) and therefore can be considered

1668-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 / APRIL 1, 2004

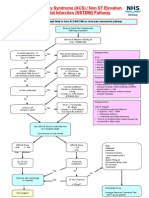

Initial Work-Up for Suspected TIA

FIGURE 1. Initial work-up for the patient with possible transient ischemic attack (TIA). (IV =

intravenous; tPA = tissue-type plasminogen activator; CT = computed tomography; ECG = elec-

trocardiography; PT = prothrombin time; aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; INR =

International Normalized Ratio; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MRA = magnetic resonance

angiography)

Frequent vital signs, with attention to blood pressure* and heart rhythm

Head CT*

Cardiac monitoring: ECG

Medical and neurologic examination*

Initial laboratory tests: complete blood count with platelet count*; electrolyte,

glucose,* and renal function measurements; PT,* aPTT,* and INR*

Carotid artery evaluation

Head MRI and MRA of intracranial and neck vessels, if available and appropriate

Further testing in selected patients (see Table 3)

Is patient a candidate for

thrombolytic therapy?

Initiate aspirin therapy

within 24 to 48 hours

(if no contraindications).

Perform certain tests (*) within 25 minutes of

patients arrival in emergency department; screen

for inclusion/exclusion criteria for IV tPA therapy.

Send patient to hospital emergency

department for evaluation.

Urgent outpatient evaluation to identify

cause of TIA; if imaging studies are not

available in a timely fashion, admit patient.

Identify and treat stroke risk factors.

Begin medical therapy, including antiplatelet

therapy, as soon as possible.

Acute (did transient symptoms occur <24 to 48 hours ago)?

Confirm TIA history.

Yes No

No Yes

an important risk factor for ischemic stroke.

There appears to be a stronger data relationship

between total and low-density lipoprotein cho-

lesterol levels, as well as a protective influence

of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, in

cervical carotid artery atherosclerosis.

10

Other important information includes a

family history of stroke (including cerebral

aneurysm or hypercoagulable state), the use

of over-the-counter or illicit drugs, a history

of migraine or severe headaches, recent

head trauma, previous systemic clots and,

in a woman of childbearing age, a history of

spontaneous abortion. Certain findings may

indicate the need for special diagnostic tests

(Table 3).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Vital signs should be evaluated, includ-

ing blood pressures in both arms, to rule

out stenosis of the subclavian artery, which

may manifest as grossly asymmetric pressures.

Auscultation of the heart and neck also should

be performed. Carotid bruits, when present,

are neither highly specific nor highly sensitive

for carotid artery stenosis.

All patients with possible TIA should

receive a detailed, documented neurologic

examination, with emphasis on cognitive and

language function, cranial nerve function,

facial and limb strength, sensory function,

deep tendon reflex symmetry, and coordi-

nation. This examination can be helpful in

determining whether a patient previously had

an unrecognized stroke. It also can serve as a

baseline examination if the patients neuro-

logic status worsens or neurologic symptoms

recur. Occasionally, the neurologic examina-

tion may identify a nonischemic cause for

an acute neurologic deficit (e.g., acute radial

nerve palsy, isolated third-nerve palsy in a

patient with diabetes mellitus).

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Brain Imaging. Computed tomographic

(CT) scanning of the head without contrast

medium should be performed to identify

subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial hem-

orrhage, or subdural hematoma. Urgent iden-

tification of these conditions is critical because

neurosurgical intervention or special manage-

ment may be required.

If hemorrhage is present, treatment with tPA

or anticoagulants that may worsen central ner-

vous system bleeding should be avoided. Spe-

cial measures may be needed to manage blood

pressure if the patient is found to have hyper-

tension-mediated intracranial hematoma, and

further testing may be required if the patient is

found to have subarachnoid hemorrhage (e.g.,

cerebral angiography to rule out aneurysm).

CT scanning also can identify conditions

that mimic TIA, including tumors and other

masses (especially if hemorrhage occurs

acutely within a mass), as well as conditions

that are associated with seizures or auras.

A head CT scan can identify signs of early

brain damage or evidence of old strokes.

11,12

Finally, CT scanning of the head with contrast

medium should be performed in the febrile

patient to rule out an infectious cause or in the

patient with a suspected mass (e.g., metastatic

carcinoma, abscess).

Because of increased bony artifact in the

posterior fossa, CT scanning is not sensitive

for evaluating disease in the brainstem or

cerebellum. In these instances, magnetic reso-

nance imaging (MRI) is the preferred study.

Electrophysiologic Testing. All patients should

have a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) with

rhythm strip.

6,12,13

If the ECG is abnormal or the

patient has a history of cardiac disease, echocar-

diography should be performed. Atrial fibrilla-

tion and left ventricular hypertrophy (suggest-

ing unrecognized chronic hypertension) are

important risk factors for stroke. Recent data

suggest that the 90-day risk for a cardiac event

TIA

APRIL 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-1669

Conditions that may mimic TIA include glucose derangement,

migraine, seizure, postictal states, tumors or, rarely, multiple

sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

is seven times higher in patients with TIA and

abnormal ECG findings than in those with a

normal ECG (4.2 versus 0.6 percent).

13

If the ECG is unrevealing, cardiac moni-

toring in selected patients could help diag-

nose paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (or other

arrhythmias in patients with syncope or pal-

pitations). In patients with untreated atrial

fibrillation, echocardiography may identify

a thromboembolic source or left ventricular

systolic dysfunction, both of which are com-

mon predictors of ischemic stroke.

14

Transesophageal echocardiography is super-

ior to transthoracic echocardiography for eval-

uating possible dysfunction of the left atrium

(including thrombus) or a patent foramen

ovale (an etiology for paradoxical emboli),

atrial septal defects (including aneurysm), and

aortic plaque. Recent clinical trials

15,16

suggest

that transesophageal echocardiography should

be considered in patients without an identifi-

able cause of TIA or known cardiac disease,

because it may detect a condition requiring

therapeutic intervention (e.g., anticoagulation

for thrombus). Aortic plaque, which has been

associated with stroke, can be visualized well on

transesophageal echocardiography.

Laboratory Tests. A complete blood count

with platelet count should be obtained to rule

out polycythemia, thrombocytopenia, and

thrombocytosis. It is helpful to know the pro-

thrombin time (PT), activated partial throm-

boplastin time (aPTT), and International

Normalized Ratio (INR) before antiplatelet or

anticoagulation therapy is administered; the

PT, aPTT, and INR can be elevated in some

hypercoagulable states.

The glucose level should be determined to

1670-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 / APRIL 1, 2004

TABLE 3

Further Diagnostic Testing Based on the History in Patients Undergoing Evaluation for Possible TIA*

History Implications Tests

Headache in postpartum Venous thrombosis MRI with venography or cerebral angiography

or dehydration setting

Fever Subacute or acute bacterial Blood cultures, head CT scan with and without contrast medium;

endocarditis in selected patients with confirmed bacterial endocarditis,

perform cerebral angiography to rule out a mycotic aneurysm.

Confusion, headache, CNS vasculitis Cerebral angiography, ESR, lumbar puncture (to look for elevation of

seizure white blood cell counts in particular)

Hypertensive encephalopathy Careful blood pressure monitoring in intensive care setting; consider

MRI.

Rheumatologic disease, CNS vasculitis Consider cerebral angiography, ESR, lumbar puncture (to look for

sympathomimetic drug use elevation of white blood cell counts in particular).

Recent myocardial infarction Cardioembolic source Transthoracic or esophageal echocardiography

Head, neck, jaw pain, Carotid or vertebral dissection Consider cerebral angiography or other neck neuroimaging studies

especially after trauma (see text).

Abrupt onset of severe Subarachnoid hemorrhage Emergency head CT scan; if the scan is negative, evaluate

headache with cerebrospinal fluid for elevated red blood cell count or perform

photophobia, or cerebral angiography to rule out aneurysm or arteriovenous

recent syncope malformation.

Confusion, stupor, coma, Vertebrobasilar ischemia Consider intracranial magnetic resonance angiography or cerebral

other brainstem symptoms angiography; if basilar artery is significantly thrombosed, consider

(poor prognosis) intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy (if available).

Brain swelling, impending Immediate head CT scan; if the scan is positive, emergency

herniation neurosurgical intervention may be required.

No obvious risk factors Cryptogenic stroke, patent Consider cerebral angiography, transesophageal echocardiography,

for stroke foramen ovale, intra-atrial and work-up for hypercoagulable state.

septal aneurysm, valvular

or aortic arch disease

TIA = transient ischemic attack; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; CNS = central nervous system;

ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

*The initial work-up for the patient with possible TIA is outlined in Figure 1.

rule out hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia and to

help diagnose occult diabetes. Blood urea nitro-

gen and creatinine levels are important, because

poor renal status may prohibit the use of con-

trast media in imaging studies. An erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) should be obtained to

potentially rule out vasculitis. Finally, a drug of

abuse screen, a pregnancy test, a homocystine

level determination, or a blood alcohol level

measurement should be performed in selected

patients.

Follow-Up Evaluation

LIPID PROFILE

After the initial more abbreviated evalua-

tion in the emergency department, risk factors

for stroke can be reassessed thoroughly later

in the evaluation. Recent data indicate that

treatment with statins (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-

glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors)

reduces the risk of stroke by about 30 percent

in patients with CHD.

17,18

Therefore, a fasting

lipid profile reflective of the patients normal

eating habits should be obtained, and statin

therapy should be initiated if indicated.

HYPERCOAGULABLE STATES

Patients with known risk factors for stroke

and those with a history of migraine, sponta-

neous abortion, pulmonary emboli, or deep

venous thrombosis, or a family history of any

of these conditions, should be evaluated for

hypercoagulable states. Initial tests include

ESR, antinuclear antibody test, rapid plasma

reagent test, and antiphospholipid antibody

tests. Referral to a hematologist or neurolo-

gist can ensure cost-effective evaluation of

the multiple coagulation-factor abnormalities

and conditions that can cause embolic stroke.

TESTING FOR ARTERIAL PATENCY

AND BLOOD FLOW

Carotid duplex ultrasonography should be

performed in a reliable laboratory, preferably

one with validation against the results of cere-

bral angiography. Alternatively, cerebral and

cervical vessels can be evaluated by magnetic

resonance angiography (MRA) with contrast

medium or by CT angiography. If the work-

up demonstrates carotid or other large-vessel

atherosclerotic disease in the patient with TIA

and unrecognized CHD, coronary artery test-

ing is recommended.

19

MRI. Clear advantages of MRI of the brain

over CT scanning of the head include better

imaging of tissues (i.e., greater sensitivity for

early edema), superior imaging within the

posterior fossa (including the brainstem and

cerebellum), additional planes of imaging

(sagittal, coronal, and oblique), and no expo-

sure to radiation.

A clear disadvantage of brain MRI is that it

may or may not identify hemorrhage. For this

reason, although MRI can be helpful, it should

not replace urgent CT scanning of the head in

the initial work-up of patients with possible

TIA. When cerebrovascular malformation,

aneurysm, cerebral venous thrombosis, or arte-

ritis is suspected, MRI or MRA is preferred.

Diffusion-weighted imaging detects cellular

edema as early as 10 to 15 minutes after symp-

tom onset. However, this technique is not yet

widely available.

MRA. This imaging modality is a noninva-

sive means of assessing intra- and extracranial

vessels. Current MRA techniques use intrave-

nously administered contrast medium (gado-

linium) to visualize the vessels.

MRA with the administration of con-

trast medium also is effective in identify-

ing vertebrobasilar stenosis, although recent

data suggest that intracranial vertebral artery

disease can be missed.

20

Depending on the

MRA acquisition technique, the percent-

age of intracranial vessel stenosis can be

overestimated (sensitivity of approximately

85 percent compared with cerebral angiog-

raphy).

21

Therefore, if accuracy is therapeu-

tically important, cerebral angiography is

necessary.

When near occlusion of the carotid artery

cannot be distinguished from complete occlu-

sion on MRA or carotid Doppler ultrasound

studies, cerebral angiography should be con-

TIA

APRIL 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-1671

sidered. Surgery generally cannot be per-

formed on completely occluded vessels.

Special consideration should be given to

patients who present with a history or symp-

toms that suggest arterial dissection. This con-

dition can be diagnosed using neck MRI scans

in certain sequences that can identify hemor-

rhage within the vessel wall (T

1

-weighted

images with fat suppression).

Patients with carotid artery dissection can

present with acute or subacute unilateral

neck, head, or jaw pain. These symptoms may

be associated with visual or language deficits,

or with sensorimotor deficits, particularly in

the opposite arm. More typically, patients

with carotid artery dissection present with

only some of these features, such as temporal

headache with lateral neck pain and, possi-

bly, transient visual obscuration (amaurosis

fugax) because of thromboemboli in the oph-

thalmic artery.

Both carotid and vertebral artery dis-

sections have been described after trauma,

although spontaneous dissection also is com-

mon. Patients should be evaluated for con-

nective tissue disease because of the associated

increased risk of dissection.

If the MRI or MRA study is inconclusive,

cerebral angiography should be used to rule

out arterial dissection or better define the

percentage of vessel narrowing.

CT Angiography. This modality is another

state-of-the-art technique for detecting

blood flow to the brain. CT angiography also

is becoming a useful imaging modality for

identifying carotid or vertebral artery dissec-

tion. Because the technique requires venous

injection of contrast dye, the patients renal

status should be considered before the test is

performed.

Conventional CT scanning in combination

with CT angiography currently is being evalu-

ated as an addition to the diagnostic imaging

tools for use in patients with TIA or stroke.

This combination can provide useful infor-

mation about vascular anatomy (in the form

of three-dimensional reconstructions) and

the extent and location of infarction. It may

allow rapid evaluation of patients with TIA or

stroke in hospitals or institutions that do not

have MRI capability.

Cerebral Angiography. This technique con-

tinues to be the gold standard for complete

evaluation of intracranial and extracranial ves-

sels. With cerebral angiography, both arterial

and venous phases of cerebral blood flow can

be visualized (dynamic study). However, cere-

bral angiography is an invasive technique that

can result in neurologic complications (total

incidence rate: 1.3 to 4.6 percent),

22,23

includ-

ing major stroke or death in 0.1 to 1.3 percent

of patients, depending on the study.

24,25

Relative indications for cerebral angiog-

raphy include suspected carotid dissection

unconfirmed on a noninvasive neuroimaging

study, subarachnoid hemorrhage (to identify

bleeding source), intracerebral hemorrhage in

the absence of hypertension, and vasculitis. If

one of these conditions is suspected, referral

to a neurologist can be helpful in obtaining

and interpreting the angiogram.

Special Considerations

VERTEBROBASILAR ISCHEMIA

Typical signs and symptoms of ischemic

syndromes involving the anterior and pos-

terior circulations are listed in Table 4. The

brainstem and cerebellum are confined within

the posterior fossa, a bony cavity with poor

tolerance of brain swelling or mass effects

(e.g., from hemorrhage). Because brainstem

structures are essential for preserving criti-

cal respiratory function and arousal states,

1672-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 / APRIL 1, 2004

The Author

NINA J. SOLENSKI, M.D., is associate professor of neurology and a staff member of the

Stroke Center at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Charlottesville. Dr.

Solenski received her medical degree from Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jeffer-

son University, Philadelphia, and completed a neurology residency and cerebrovascular

fellowship at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center.

Address correspondence to Nina J. Solenski, M.D., Stroke Center, Department of

Neurology, P.O. Box 800394, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, Hospital

Dr., McKim Hall, Room 2055, Charlottesville, VA 22908 (e-mail: njs2j@virginia.edu).

Reprints are not available from the author.

patients with vertebrobasilar ischemia should

be monitored closely. It also is crucial to search

for life-threatening cerebrovascular disease,

such as basilar artery stenosis or thrombosis

or disease affecting multiple large vessels (e.g.,

bilateral, vertebral, or carotid artery stenosis).

TIA IN A YOUNG PATIENT

When a TIA occurs in a patient younger

than 45 years, particularly if there are no clear

risk factors for stroke, it is advisable to refer

the patient to a neurologist for consideration

of specialized testing. For example, it may be

necessary to determine the utility of cerebral

angiography to rule out vasculitis, carotid

artery dissection, and other forms of nonath-

erosclerotic vasculopathy, or lumbar spinal

puncture with cerebrospinal fluid evaluation

may be required to rule out chronic infection

or inflammation.

Because cardiac abnormalities are among

the most common causes of TIA in young

patients, a baseline ECG with rhythm strip

should be obtained, and transthoracic and

transesophageal echocardiography should be

considered. A toxicology screen for drugs

of abuse (especially sympathomimetic com-

pounds) usually is performed.

Several newly identified, genetically based

metabolic and hematologic syndromes have

been found to be associated with stroke. With

some of these syndromes, initial symptoms

occur in the younger years (late childhood,

adolescence, or early adulthood). Diagnosis

of these syndromes may require specialized

tests. Such testing could be important to bet-

ter define treatment options and prognosis, as

well as to identify family members who may

APRIL 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-1673

TABLE 4

Typical Characteristics of Ischemic Syndromes Involving the Anterior and Posterior Circulations

Ischemic syndrome:

circulation involved Signs Symptoms

Anterior circulation* Visual-field cut Inability to see well (i.e., difficulty reading or driving

Language dysfunction (left hemisphere most Difficulty finding or understanding words, inability to read,

often affected): aphasia garbled or slurred speech

Motor dysfunction: contralateral face, arm, Dropping objects; depending on severity, inability to lift

or leg weakness or move a body part or objects

Sensory dysfunction: contralateral increased Tingling (paresthesias), numbness, or pain

or decreased sensation to pain, heat, or cold

Behavior dysfunction (right hemisphere): The patient usually reports no symptoms, but family

inattention to surrounding environment, members or others report that the patient has difficulty

particularly to one side; if severe, patient dressing, ignores half of food on a plate, or has poor

may deny deficits or even his or her own attention to one side of the room or to someone speaking

body parts to the patient on one side versus the other (most often,

the left side is ignored).

Posterior circulation Nystagmus Vertigo (spinning sensation)

Disconjugate gaze If subtle, blurry or double vision

Homonymous visual-field cut Inability to see well, especially to one side

Contralateral weakness Dropping objects, inability to fully lift or move the limb

Incoordination of trunk or limbs (ataxia) Clumsiness, falling, inability to coordinate an action

(e.g., drink from a cup without spilling contents)

Motor or sensory dysfunction on opposite For example, the patient may report double vision,

side of cranial nerve deficits (crossed signs droopiness on the left side of the face, and dragging

suggest brainstem involvement) of the right leg (because of weakness).

Bilateral signs Abrupt weakness of both legs, falling

Decreased mentation; stupor or coma Family members or others report that the patient has poor

responsiveness or that they are unable to arouse the patient.

*Includes the internal carotid artery, middle cerebral artery, and anterior cerebral artery, as well as the branches of these arteries.

Includes the vertebral arteries, basilar artery, and posterior cerebral artery, as well as the branches of these arteries.

TIA

be at risk for TIA or stroke.

The author indicates that she does not have any con-

flicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

REFERENCES

1. Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, Fayad PB, Mohr

JP, Saver JL, et al. Transient ischemic attackpro-

posal for a new definition. N Engl J Med 2002;

347:1713-6.

2. Johnston CS, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S.

Short-term prognosis after emergency department

diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284:2901-6.

3. Johnston CS. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J

Med 2002;347:1687-92.

4. Warburton E. Stroke management. Clin Evid 2003;

(9):206-20.

5. Sudlow C, Gubitz G, Sandercock P, Lip G. Stroke

prevention. Clin Evid 2003;(9):221-45.

6. Adams HP Jr, Adams RJ, Brott T, del Zoppo GJ,

Furlan A, Goldstein LB, et al. Guidelines for

the early management of patients with ischemic

stroke: a scientific statement from the Stroke

Council of the American Stroke Association. Stroke

2003;34:1056-83.

7. Gorelick PB, Sacco RL, Smith DB, Alberts M, Mus-

tone-Alexander L, Rader D, et al. Prevention of a

first stroke: a review of guidelines and a multidis-

ciplinary consensus statement from the National

Stroke Association. JAMA 1999;281:1112-20.

8. Diagnosis and initial treatment of ischemic stroke.

Released October 2003. Accessed online February

20, 2004, at http://www.icsi.org/knowledge/detail.

asp?catID=29&itemID=166.

9. Sacco RL, Wolf PA, Gorelick PB. Risk factors and

their management for stroke prevention: outlook

for 1999 and beyond. Neurology 1999;53(7 suppl

4):S15-24.

10. Reed DM, Resch JA, Hayaski T, MacLean C, Yano

K. A prospective study of cerebral atherosclerosis.

Stroke 1988;19:820-5.

11. Albers GW, Hart RG, Lutsep HL, Newell DW,

Sacco RL. AHA scientific statement. Supplement

to the guidelines for the management of transient

ischemic attacks: a statement from the Ad Hoc

Committee on Guidelines for the Management of

Transient Ischemic Attacks, Stroke Council, Ameri-

can Heart Association. Stroke 1999;30:2502-11.

12. Culebras A, Kase CS, Masdeu JC, Fox AJ, Bryan RN,

Grossman CB, et al. Practice guidelines for the use

of imaging in transient ischemic attacks and acute

stroke. A report of the Stroke Council, American

Heart Association. Stroke 1997;28:1480-97.

13. Elkins JS, Sidney S, Gress DR, Go AS, Bernstein AL,

Johnston SC. Electrocardiographic findings predict

short-term cardiac morbidity after transient isch-

emic attack. Arch Neurol 2002;59:1437-41.

14. Echocardiographic predictors of stroke in patients

with atrial fibrillation: a prospective study of 1066

patients from 3 clinical trials. Arch Intern Med

1998;158:1316-20.

15. OBrien PJ, Thiemann DR, McNamara RL, Roberts

JW, Raska K, Oppenheimer SM, et al. Usefulness

of transesophageal echocardiography in predicting

mortality and morbidity in stroke patients without

clinically known cardiac sources of embolus. Am J

Cardiol 1998;81:1144-51.

16. Labovitz AJ. Transesophageal echocardiography

and unexplained cerebral ischemia: a multicenter

follow-up study. The STEPS Investigators. Signifi-

cance of Transesophageal Echocardiography in the

Prevention of Recurrent Stroke. Am Heart J 1999;

137:1082-7.

17. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444

patients with coronary heart disease: the Scan-

dinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet

1994;344:1383-9.

18. Plehn JF, Davis BR, Sacks FM, Rouleau JL, Pfeffer

MA, Bernstein V, et al. Reduction of stroke inci-

dence after myocardial infarction with pravastatin:

the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE)

study. The CARE Investigators. Circulation 1999;

99:216-23.

19. Adams RJ, Chimowitz MI, Alpert JS, Awad IA,

Cerqueria MD, Fayad P, et al. Coronary risk evalua-

tion in patients with transient ischemic attack and

ischemic stroke: a scientific statement for health-

care professionals from the Stroke Council and the

Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American

Heart Association/American Stroke Association.

Circulation 2003;108:1278-90.

20. Bhadelia RA, Bengoa R, Gesner L, Patel SK, Uzun

G, Wolpert SM, et al. Efficacy of MR angiography

in the detection and characterization of occlusive

disease in the vertebrobasilar system. J Comput

Assist Tomogr 2001;25:458-65.

21. Korogi Y, Takahashi M, Nakagawa T, Mabuchi N,

Watabe T, Shiokawa Y, et al. Intracranial vascular

stenosis and occlusion: MR angiographic findings.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:135-43.

22. Hankey GJ, Warlow CP, Sellar RJ. Cerebral angio-

graphic risk in mild cerebrovascular disease. Stroke

1990;21:209-22.

23. Willinsky RA, Taylor SM, Ter Brugge K, Farb RI,

Tomlinson G, Montanera W. Neurologic complica-

tions of cerebral angiography: prospective analysis

of 2,899 procedures and review of the literature.

Radiology 2003;227:522-8.

24. Dion JE, Gates PC, Fox AJ, Barnett HJ, Blom RJ.

Clinical events following neuroangiography: a pro-

spective study. Stroke 1987;18:997-1004.

25. Young N, Chi KK, Ajaka J, McKay L, ONeill D, Wong

1674-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 69, NUMBER 7 / APRIL 1, 2004

You might also like

- Transient Ischemic AttacksDocument10 pagesTransient Ischemic AttacksfabianounifenasNo ratings yet

- Transient Ischemic Attack: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesTransient Ischemic Attack: Clinical PracticeJuanita MesaNo ratings yet

- Ait Nejm 2020Document9 pagesAit Nejm 2020Ahmed JallouliNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke Management by The Nurse PR - 2019 - The Journal For Nurse PractDocument9 pagesIschemic Stroke Management by The Nurse PR - 2019 - The Journal For Nurse PractLina SafitriNo ratings yet

- Activating A Stroke Alert - A Neurological Emergency - CE591Document7 pagesActivating A Stroke Alert - A Neurological Emergency - CE591Czar Julius Malasaga100% (1)

- Sumber 9Document18 pagesSumber 9Ali Laksana SuryaNo ratings yet

- Seizure Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury Case FileDocument7 pagesSeizure Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury Case Filehttps://medical-phd.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive CrisisDocument7 pagesHypertensive CrisisAbdul Hannan Ali100% (1)

- Nanda, A, Niranjan NS, Transient Ischemic Attack. Medscape. 2013Document6 pagesNanda, A, Niranjan NS, Transient Ischemic Attack. Medscape. 2013rahmatNo ratings yet

- A. Severe Migraine Attack B. Cluster Headache C. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage D. Hypertensive Encephalopathy E. EncephalitisDocument4 pagesA. Severe Migraine Attack B. Cluster Headache C. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage D. Hypertensive Encephalopathy E. EncephalitisVgdgNo ratings yet

- SBR 4Document16 pagesSBR 4YuhuNo ratings yet

- Drug Treatment For Hypertensive Emergencies: New Concepts and Emerging Technologies For Emergency PhysiciansDocument0 pagesDrug Treatment For Hypertensive Emergencies: New Concepts and Emerging Technologies For Emergency PhysiciansRajihah JihahNo ratings yet

- Yncope Earning Bjectives: EfinitionDocument5 pagesYncope Earning Bjectives: EfinitionmuhammadridhwanNo ratings yet

- TIA NeneDocument13 pagesTIA NenekenNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of SyncopeDocument11 pagesEvaluation of Syncopebluecrush1No ratings yet

- Syncope - Electrocardiographic and Clinical CorrelationDocument16 pagesSyncope - Electrocardiographic and Clinical CorrelationNANDY LUZ FERIA DIAZNo ratings yet

- Cerebro-Vascular Disease & Stroke: Faizan Zaffar KashooDocument57 pagesCerebro-Vascular Disease & Stroke: Faizan Zaffar KashooDrGasnasNo ratings yet

- HSA Controversias 2016Document9 pagesHSA Controversias 2016Ellys Macías PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Stroke 1. Disease/DisorderDocument11 pagesStroke 1. Disease/DisorderBiandaNo ratings yet

- Article Acute Stroke PDFDocument10 pagesArticle Acute Stroke PDFHeather PorterNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Emergencies SyncopeDocument10 pagesCardiovascular Emergencies SyncopeilltekneexzNo ratings yet

- Post Stroke ComplicationsDocument33 pagesPost Stroke Complicationsdiijah678100% (1)

- Nursing Care Management 103 Related Learning Experience Health TeachingDocument10 pagesNursing Care Management 103 Related Learning Experience Health Teachingkarenfaye00No ratings yet

- 3390-Article Text-1555-3802-10-20200606Document12 pages3390-Article Text-1555-3802-10-20200606Mayara Bongestab ParteliNo ratings yet

- Neurological EmergenciesDocument11 pagesNeurological Emergenciespunit lakraNo ratings yet

- Guide To ECT 2015Document25 pagesGuide To ECT 2015Diana CalderónNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular DisordersDocument20 pagesCerebrovascular DisordersPrimas Shahibba RidhwanaNo ratings yet

- 8 StrokeDocument8 pages8 StrokeAhmed aljumailiNo ratings yet

- Guidelines & Protocols: Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - Management and Prevention Advisory CommitteeDocument13 pagesGuidelines & Protocols: Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - Management and Prevention Advisory CommitteeAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Jamieson 2009Document7 pagesJamieson 2009JovitaNo ratings yet

- Neurologic EmergenciesDocument11 pagesNeurologic EmergenciesRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Askep StrokeDocument46 pagesAskep Strokesybilla17No ratings yet

- Ischemic StrokeDocument13 pagesIschemic StrokearthurbaidoodouglasNo ratings yet

- The Pathophysiology of Ischemic Strokes Is Widely Known. Ischemic Strokes Are TheDocument7 pagesThe Pathophysiology of Ischemic Strokes Is Widely Known. Ischemic Strokes Are Theprnczb13No ratings yet

- Rapid Focused Neurological Assessment in The Emergency Department and ICUDocument16 pagesRapid Focused Neurological Assessment in The Emergency Department and ICUAnnie RicoNo ratings yet

- AISDocument40 pagesAISMohamed AbdoNo ratings yet

- Seizure Versus SyncopeDocument10 pagesSeizure Versus SyncopeArmando Diaz PerezNo ratings yet

- Emergency Neurological Life Support - Subarachnoid HemorrhageDocument9 pagesEmergency Neurological Life Support - Subarachnoid HemorrhageIsabel VillalobosNo ratings yet

- 2014 CCM Review NotesDocument241 pages2014 CCM Review NotesAndres SimsNo ratings yet

- An Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyDocument8 pagesAn Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyGaneshRajaratenamNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presentation of Cerebrovascular Disease: David Griesemer, MDDocument47 pagesClinical Presentation of Cerebrovascular Disease: David Griesemer, MDPedro CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Emergencies in The Emergency DepartmentDocument13 pagesHypertensive Emergencies in The Emergency DepartmentLuis Lopez RevelesNo ratings yet

- Cec Post Fall Assess and Man June 2013Document3 pagesCec Post Fall Assess and Man June 2013Vicente TurasNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke Management by Carlos L ChuaDocument61 pagesAcute Stroke Management by Carlos L ChuaRemaica Hernadez100% (1)

- TIA: Transient Ischemic Attack Key PointsDocument2 pagesTIA: Transient Ischemic Attack Key PointsAlmahira Az ZahraNo ratings yet

- Syncope 3Document19 pagesSyncope 3Pratyush PrateekNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrhythmia ThesisDocument5 pagesCardiac Arrhythmia Thesiselizabethallencambridge100% (2)

- 1228 HFStroke Altered Neuro 2011Document74 pages1228 HFStroke Altered Neuro 2011Cyndy EnterlineNo ratings yet

- In-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackDocument15 pagesIn-Hospital Stroke Recurrence and Stroke After Transient Ischemic AttackferrevNo ratings yet

- CVADocument4 pagesCVACloyd Marvin Pajas SegundoNo ratings yet

- Dent Clin N Am 50 (2006) 625-633Document9 pagesDent Clin N Am 50 (2006) 625-633lalajanNo ratings yet

- Case-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureFrom EverandCase-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureUlrika Birgersdotter-GreenNo ratings yet

- Patient Management Problem Preferred Responses.27Document12 pagesPatient Management Problem Preferred Responses.27mhd.mamdohNo ratings yet

- ABC Emergency Differential DiagnDocument3 pagesABC Emergency Differential Diagnsharu4291No ratings yet

- Hypertensive Encephalopathy: Presentation DDX Workup Treatment MedicationDocument8 pagesHypertensive Encephalopathy: Presentation DDX Workup Treatment MedicationMoh SuriyawalNo ratings yet

- Neurology 5Document5 pagesNeurology 5Loyla RoseNo ratings yet

- Emergency Medicine Survival Guide: Emergency Medicine Survival Guide for New DoctorsFrom EverandEmergency Medicine Survival Guide: Emergency Medicine Survival Guide for New DoctorsNo ratings yet

- The Code Stroke Handbook: Approach to the Acute Stroke PatientFrom EverandThe Code Stroke Handbook: Approach to the Acute Stroke PatientNo ratings yet

- Eur J of Neuroscience - 2021 - Gorman Sandler - The Forced Swim Test Giving Up On Behavioral Despair Commentary OnDocument4 pagesEur J of Neuroscience - 2021 - Gorman Sandler - The Forced Swim Test Giving Up On Behavioral Despair Commentary OnAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@0471141755 ph0508s38Document11 pages10 1002@0471141755 ph0508s38Andi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire Gerd Q Score in Gerd Patients Treated With dlbs2411 Compared To Omeprazole 2skpDocument1 pageGastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire Gerd Q Score in Gerd Patients Treated With dlbs2411 Compared To Omeprazole 2skpAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- The Forced Swim Test For Depression-Like Behavior in RodentsDocument6 pagesThe Forced Swim Test For Depression-Like Behavior in RodentsAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Animal Models As Tools To Study The PathophysiologDocument10 pagesAnimal Models As Tools To Study The PathophysiologAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Warden Nature 2012 SuppDocument22 pagesWarden Nature 2012 SuppAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Anticancer Activity of Phyllanthus Niruri Linn Extract in Colorectal Cancer Patients A Phase II Clinical TrialDocument5 pagesAnticancer Activity of Phyllanthus Niruri Linn Extract in Colorectal Cancer Patients A Phase II Clinical TrialAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Mitochondrial Dynamics in Cardiovascular Medicine: Gaetano Santulli EditorDocument644 pagesMitochondrial Dynamics in Cardiovascular Medicine: Gaetano Santulli EditorAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of The mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 VaccineDocument14 pagesEfficacy and Safety of The mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccinejuan carlos monasterio saezNo ratings yet

- Anti-Collagen VII Antibody (LH7.2) Ab6312 Anti-Collagen VII Antibody (LH7.2) Ab6312Document3 pagesAnti-Collagen VII Antibody (LH7.2) Ab6312 Anti-Collagen VII Antibody (LH7.2) Ab6312Andi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Conductivity Standard MSDSDocument4 pagesConductivity Standard MSDSAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Pengantar Ilmu Biomedik Dan BiokimiaDocument27 pagesPengantar Ilmu Biomedik Dan BiokimiaAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Bahan Kuliah Id-1-2020Document63 pagesBahan Kuliah Id-1-2020Andi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Lampiran VIII - Daftar Riwayat Hidup PDFDocument1 pageLampiran VIII - Daftar Riwayat Hidup PDFAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke DiagnosisDocument8 pagesAcute Stroke Diagnosisvivek_win95No ratings yet

- General Aspects of Protein StructureDocument19 pagesGeneral Aspects of Protein StructureAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Medical Aspects 2014Document154 pagesMedical Aspects 2014Andi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point: Health Practices On Cruise Ships: Training For Employees TranscriptDocument7 pagesHazard Analysis Critical Control Point: Health Practices On Cruise Ships: Training For Employees TranscriptAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke DiagnosisDocument8 pagesAcute Stroke Diagnosisvivek_win95No ratings yet

- SCAT Systematic Cause Analysis Technique PDFDocument36 pagesSCAT Systematic Cause Analysis Technique PDFAndi Saputra100% (1)

- The Epilepsy Prescriber's Guide To Antiepileptic Drugs 2010Document333 pagesThe Epilepsy Prescriber's Guide To Antiepileptic Drugs 2010Andi SaputraNo ratings yet

- NICE Guidelines PDFDocument37 pagesNICE Guidelines PDFKahubbi Fatimah Wa'aliyNo ratings yet

- Guidelines & Protocols: Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - Management and Prevention Advisory CommitteeDocument13 pagesGuidelines & Protocols: Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - Management and Prevention Advisory CommitteeAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Ot Guidelines Stroke RehabDocument87 pagesOt Guidelines Stroke Rehab健康生活園Healthy Life GardenNo ratings yet

- Transient Ischemic Attacks: Part I. Diagnosis and EvaluationDocument10 pagesTransient Ischemic Attacks: Part I. Diagnosis and EvaluationAndi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Stroke 2010 KoreaDocument68 pagesGuidelines For Stroke 2010 KoreaNain EmberspiritNo ratings yet

- NICE Guidelines PDFDocument37 pagesNICE Guidelines PDFKahubbi Fatimah Wa'aliyNo ratings yet

- CPG Management of StrokeDocument51 pagesCPG Management of Strokeapalaginih0% (1)

- CPG Management of StrokeDocument51 pagesCPG Management of Strokeapalaginih0% (1)

- Acs Nstemi PathwayDocument3 pagesAcs Nstemi PathwayAliey's SKeplek NgeNersNo ratings yet

- ICU Liberation ABCDEF Bundle Implementation Both Spontaneous Awakening Breathing Trials SBT SATDocument63 pagesICU Liberation ABCDEF Bundle Implementation Both Spontaneous Awakening Breathing Trials SBT SATbejoNo ratings yet

- Laser Retinopexy PDFDocument4 pagesLaser Retinopexy PDFveerroxxNo ratings yet

- Vestibular Exercise For Patient - Guideline Vestibular ExerciseDocument4 pagesVestibular Exercise For Patient - Guideline Vestibular ExerciseResi Lystianto PutraNo ratings yet

- Body Mechanics and Patient CareDocument79 pagesBody Mechanics and Patient CareChristian DioNo ratings yet

- Stress Management PPT FinalDocument7 pagesStress Management PPT FinalAdarsh Meher100% (1)

- Pages From First Aid For The USMLE Step 1 2015, 25 Edition-2Document7 pagesPages From First Aid For The USMLE Step 1 2015, 25 Edition-2Mahmoud MohsenNo ratings yet

- Not GlaucomaDocument5 pagesNot GlaucomaFabio LuccheseNo ratings yet

- Essential Elements of Clinical TrialDocument39 pagesEssential Elements of Clinical TrialmisganaNo ratings yet

- Medical Claim Form - FLEX StaffDocument1 pageMedical Claim Form - FLEX StaffHerawaty Syaiful GusmentaNo ratings yet

- Resistance Training Utilization For Patients With Transverse MyelitisDocument10 pagesResistance Training Utilization For Patients With Transverse Myelitisapi-414772091No ratings yet

- 3 Intraoperative PhaseDocument28 pages3 Intraoperative Phaseada_beer100% (2)

- Trigeminal NeuralgiaDocument3 pagesTrigeminal NeuralgiaKiara PeoplesNo ratings yet

- Nutrisi EnteralDocument51 pagesNutrisi EnteralIsma Awalia Habibah14No ratings yet

- Medication, Toxic, and Vitamin-Related NeuropathiesDocument22 pagesMedication, Toxic, and Vitamin-Related Neuropathiessatyagraha84No ratings yet

- Ophthalmology PDFDocument28 pagesOphthalmology PDFKukuh Rizwido PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Medicine Quality IndicatorsDocument14 pagesLaboratory Medicine Quality IndicatorskinnusaraiNo ratings yet

- Surgical SafetyDocument23 pagesSurgical SafetyNimi BatuboNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity of The Turkish Version of The Job Performance Scale InstrumentDocument9 pagesReliability and Validity of The Turkish Version of The Job Performance Scale InstrumentsatmayaniNo ratings yet

- Guia Tiva 2018Document14 pagesGuia Tiva 2018John Bryan Herrera DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis (The Disease)Document24 pagesTuberculosis (The Disease)DiLahNo ratings yet

- VIDATOX ® 30 CH EnglishDocument17 pagesVIDATOX ® 30 CH EnglishmusicaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Presenting With Priapism 2329 6917 1000171Document5 pagesChronic Myeloid Leukemia Presenting With Priapism 2329 6917 1000171SalwiyadiNo ratings yet

- An Implantable Bioartificial Kidney For Treating Kidney FailureDocument2 pagesAn Implantable Bioartificial Kidney For Treating Kidney FailureAnugrah Pangeran100% (1)

- Tendon TransferDocument1 pageTendon TransferPandi Smart VjNo ratings yet

- Indian Ethos and Values in ManagementDocument23 pagesIndian Ethos and Values in ManagementDinesh Babu PugalenthiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 PsychDocument12 pagesChapter 3 Psychred_gyrl9282No ratings yet

- Merci Ships Annual Report Cpr-31Document32 pagesMerci Ships Annual Report Cpr-31larryfoleNo ratings yet

- Total Patient Care Nursing or Case Method NursingDocument3 pagesTotal Patient Care Nursing or Case Method Nursingkint manlangitNo ratings yet

- Pub104 WorkbookDocument16 pagesPub104 Workbooksyang9No ratings yet