Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Millennium Stone Fiasco

Uploaded by

Brian JohnCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Millennium Stone Fiasco

Uploaded by

Brian JohnCopyright:

Available Formats

The Millennium Stone Fiasco

Brian John

An extract from Chapter Three of The Bluestone Enigma (Greencroft Books, 2008, 160 pp, 9.95)

This is a sad tale of a bluestone which was apparently jinxed.

Fourteen years after the event, we can look back on what happened

with more than a little amusement, but at the time the stone was the

key component in a serious piece of experimental archaeology,

designed to demonstrate how 82 bluestones might have been

transported from the far west of Wales to Stonehenge by our

Neolithic ancestors.

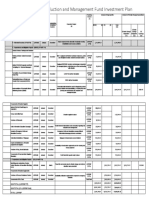

In the year 2000 at least 100,000 was spent on the

Millennium Stone Project in Pembrokeshire, in which it was

planned to transport a single block of bluestone from near

Mynachlogddu (the closest village to Carn Meini) to

Stonehenge, using the techniques on land and over water that

might have been familiar to Neolithic tribal groups. The

organizers (a community initiative called Menter Preseli)

claimed that the objectives were to celebrate the millennium,

to focus on community engagement and to raise the prole of

Pembrokeshire. However, it was inevitable that the media,

and Stonehenge watchers generally, saw it as something

much more signicant -- and even scientic.

In April 2000, project organizer Philip Bowen and geologist

Sid Howells found a perfect bluestone lying conveniently in

a farmer's eld near Mynachlogddu, close to the road and some distance from its natural outcrop in the

Preseli Hills. It was about the right size, and was long, slender and slightly bulbous at one end. Its estimated

weight was 3 tonnes. The initial plan was to move the stone on wooden rollers --- but, as the project relied

on using volunteers, that was vetoed for health and safety reasons. It was a London engineer, Nick Price,

who came up with the idea of using a large wooden sled with ropes and two 6 m long poles to use as levers.

The stone would be attached to the sled with heavy duty nylon rope, and the pullers would work in pairs,

using wooden bars and connecting ropes. They would not pull, but push on the crossbars at chest height,

always facing forward, with the sled sliding smoothly along behind. The levers would be used to help the

stone. It was estimated that 25 pullers would be adequate for most of the time, but with more drafted in for

steep hill-climbs. Following a trial, it was calculated that the stone could be dragged in this fashion for

about three miles in a day. The plan was to reach the Eastern Cleddau River in a week or so, using around 30

volunteers. That was changed when it was realized that volunteers in sufcient quantity would only be

available during weekends. So the pulling would be done for the most part on Saturdays and Sundays. The

stone would be parked up and guarded during the other days of each working week. Nonetheless, the

ambition was to cover the whole 240-mile journey (including the river and sea stretches) to Stonehenge in

about six months, allowing for spells of bad weather and inactivity.

The plan, as it evolved, was based quite closely on the suggestions of Richard Atkinson many years

earlier. There would be three segments to the bluestone journey. First, an overland pull of about 17 miles.

Second, a down-river journey to Milford Haven and a coastal voyage (with stopping-off points in

Carmarthen, Swansea and Cardiff) up the Bristol Channel and across to Avonmouth, near Bristol. From

there the huge stone was to be carried in a Third Stage, by barge along the River Avon and the Kennet and

Avon canal before being dragged the nal 26 miles to Stonehenge. On arrival it would be blessed by Druids

at the autumn solstice in September.

Things started to go wrong almost immediately. At 4 pm on the rst day of pulling the organizers

Page 1

stopped and realised that the

distance travelled had been only

one mile. Now that was a

sobering moment, said Philip

Bowen. The major problem

was that the sled didn't move on

the modern road surfaces......

A low-friction nylon net was

found to help, but almost all of

the pulling route had to be on 17

miles of roads and public access

lanes. There was no genuine

cross-country transport at all.

But there was gradual progress,

and great cameraderie among

the pullers. The stone was

affectionally christened Elvis

Preseli.

All of the volunteers had

to be listed, checked in and out,

and allocated pulling days. The

insurers insisted that the pullers

should not dress up in their

Neolithic outts, and that they should wear gloves when pulling and pushing. Moving the stone also meant

that the organizers needed back-up facilities provided by the police, re service, council workmen, St John's

Ambulance staff, local transport companies, safety experts, divers and the armed forces. Then there were

portaloos, quad bikes, lorries and catering supplies. That all cost money. A massive logistical exercise was

made even more difcult by terrible weather conditions. Although things got tough and the project fell

further and further behind schedule, the enthusiasm of most the pullers (myself included!) never faltered.

But pulling was very hard work. Along with the volunteers from all over the UK, people turned up to help

from Europe and even from Australia. A magician called Mystic Merlin, dressed in full regalia, was in

attendance for most of the pull, and did his fair share of strenuous pulling. But some pullers did go missing

after a few days of working in the rain, and as exhaustion set in. Philip and his team found it difcult to nd

the numbers needed to keep the act on the road.

Page 2

Low-friction nylon netting is brought in to assist in the

sliding of the sledge on asphalt surfaces.

The pullers (or pushers) moving the stone on its sledge, on an easy section of roadway.

Then something happened which

caused real frustration and anger.

When the team turned up for the day

of the penultimate pull near the

village of Llawhaden they found that

a tribal marauding party had struck!

Someone had managed to lift the

stone off its sled, presumably using

farm machinery. The sled itself had

disappeared. The police were called,

and the media loved the story. A

search party was sent out, and

fortunately, one of the volunteers

found the sled in a nearby wood. A

crane had to be hired to put the stone

back on its Neolithic conveyance.

When things had calmed down, the

pull continued, and at last the weary

warriors reached Blackpool Mill, near

the head of navigation on the Eastern

Cleddau River, on 29th May 2000.

The rst stretch of the journey had

taken more than a month to complete,

with ve weekends of pulling. The

plan was that there should now be a

rendezvous with two magnicent

Page 3

Luckily, nobody was injured when the

sledge and its precious load went out of

control on a hill near Llawhaden. There

was no effective braking system.....

One of the splendid curraghs built by Ron Rees. Two

were built. They were designed to be propelled by eight

rowers.

custom-built curraghs made by Ray

Rees in Carmarthen. They would be

roped together to form a sort of

pontoon, and would be moved by ten

experienced rowers, ve on each side.

Instead of mounting the stone on a

platform well above the water-line (as in

the 1954 Atkinson experiment) it was

decided that there would be greater

stability if the stone was slung beneath

the water line, with the weight

supported on beams across the decks of

the two vessels.

At Blackpool Mill the stone (still

on its sledge) was slid on rollers down

into the water. That proved a very

difcult task, even on a nicely sloping

piece of river bank. The stone was tied

up with heavy-duty webbing slings and

had oats and buoys attached. The plan

was that the curraghs would then come

up on the tide, pick up the stone and

transport it downstream to Milford

Haven. However, it transpired that

after heavy rain the tidal currant was

too strong for the curraghs to be rowed

up-river, even on a rising tide, so they

had to be towed by an inatable safety

boat with a powerful outboard engine.

At last they were manoeuvred into

position near the shore, and after many

failed attempts to pick up the stone,

modern technology had to be called in

again. A heavy lift crane was hired to

lift the stone into deeper water where

the curraghs could position themselves

directly over it. Then the crane got

bogged down and had to be pulled out

by a JCB. With the tide now falling, the

curraghs had to be tied up overnight.

On the next high tide the volunteers and

safety experts resumed work, and nally

(with the intervention of modern

technology) managed to lift the stone off

the bed of the river and sling it between

and beneath the two curraghs. On the

high tide, to the accompaniment of great

cheers, the stone was moved to the

centre of the river and carried down-

river to Milford Haven on June 3rd.

Then another catastrophe

occurred when the voyage from the

sheltered waters of Milford Haven

commenced, with the prospect of open

sea ahead. The bluestone was strapped

between the two boats in its sling and

Page 4

The two curraghs xed together at Blackpool Bridge,

with the supporting platform ready to receive the

stone.

The stone is hauled over Blackpool Bridge. Note that

the pullers are working two abreast, with four ropes

in use.

Page 5

Levers had to be used frequently during the pull, to ensure that the sledge did not deviate

from its proper route. Nevertheless, there was much swinging to right and left.........

A heavy lift crane is used at Blackpool Mill, to move the stone into the water of the

Eastern Cleddau River.

seemed perfectly secure. But in awful

weather conditions, and with a BBC

documentary team in attendance, the rowers

found it increasingly difcult to make

headway, and there were thoughts of

retreating back intthe shelter of the

waterway. Then, as the rowers encountered

the swell coming in through the heads of

the waterway a section of heavy nylon

strapping snapped. The ill-fated stone

slipped out of its sling and and came to rest

on the sea bed, in the middle of a major

shipping lane. There was more national

media coverage, and sections of the media

referred gleefully to the bluestone jinx..

Divers went down in 20m of water and

eventually managed to locate the stone.

Eleven days later a salvage team raised it

with a oating crane. The stone was placed

on the deck of a salvage vessel and returned

to dry land in Milford Docks.

Page 6

A team of divers tried to recover the stone from

the bed of Milford Haven

Safe again! The stone is recovered from the depths and is slung onto a pontoon, to be

delivered back to Milford Docks.

Worse was to follow. While the stone was still parked on the quayside ready for the journey out into

the Celtic Sea and up the Bristol Channel, the organizers had to confront further problems. The curragh

pontoon and sling technique was abandoned on the grounds that if it did not work in a slight swell inside

Milford haven it would certainly not work in the open sea. A new barge was brought in, but it was found

that the stone would not sit safely on its deck. Then the project insurers withdrew their backing and the

project ground to a halt. In a welter of recrimination, accusations were levelled at the local authority, the

organizers and even the National Lottery Heritage Fund for a massive waste of 100,000. There were

rumours that the real cost of the exercise was a great deal more than that, and that the Lottery was asking for

its money back. In reality they never did pay more than 53,000, and the rest of the funds came (in various

convoluted ways) from public funds via the County Council. There was nothing more that could be done.

With the funding exhausted, Menter Preseli was wound up. Long-suffering organizer Philip Bowen moved

on to other work, and the stone was stranded in its safety enclosure near Milford Docks for more than two

years. At long last, in January 2003, the bluestone got a new home in the National Botanic Garden of Wales.

There was no Neolithic pantomime this time. Off it went on its at-bed truck. On arrival it was blessed by a

druid, and it is still there to this day.

It would be uncharitable to call the Millennium Stone Project an unmitigated disaster, since it gave

people a lot of fun and kept the media gainfully employed. Some people became very angry about the

perceived waste of public money -- but there were other Millennium Projects that were much more futile

and badly run. On balance, looking at things from a scientic standpoint, I think the money was well spent.

Far from proving that the human transport theory was sound, the exercise proved to be far beyond the

capacity of the organizers, even with the assistance of willing helpers, asphalted roads, and a vast array of

modern machines, specialist materials and and communications technology. It led many people to the

conclusion that the transport of one smallish 3-tonne bluestone monolith, let alone 80 or so, would have been

incredibly difcult, if not impossible, around 5,500 years ago, no matter what romantic ideas some

archaeologists might hold sacred.

==================================================.

Thanks to Iain Sewell for the photographs used in this article

Page 7

You might also like

- Walking on Gower: 30 walks exploring the AONB peninsula in South WalesFrom EverandWalking on Gower: 30 walks exploring the AONB peninsula in South WalesNo ratings yet

- English Task Answering Questions: StonehengeDocument2 pagesEnglish Task Answering Questions: StonehengeKulsum QatrunnadaNo ratings yet

- GEO - A350 Semington Bypass Oxford Clay Exposures (Bath Geol Soc, 2004)Document6 pagesGEO - A350 Semington Bypass Oxford Clay Exposures (Bath Geol Soc, 2004)sandycastleNo ratings yet

- The England Coast Path: 1,000 Mini Adventures Around the World's Longest Coastal PathFrom EverandThe England Coast Path: 1,000 Mini Adventures Around the World's Longest Coastal PathNo ratings yet

- Ancient City's Stones Levitated by SoundDocument42 pagesAncient City's Stones Levitated by SoundlisanewlinNo ratings yet

- The Kennet and Avon Canal: The full canal walk and 20 day walksFrom EverandThe Kennet and Avon Canal: The full canal walk and 20 day walksNo ratings yet

- Dash To The Source of The Sepik River: and To The Sources of The Sand and North Rivers As Far As The Coastal RangeDocument36 pagesDash To The Source of The Sepik River: and To The Sources of The Sand and North Rivers As Far As The Coastal RangeuscngpNo ratings yet

- The Greywacke: How a Priest, a Soldier and a School Teacher Uncovered 300 Million Years of HistoryFrom EverandThe Greywacke: How a Priest, a Soldier and a School Teacher Uncovered 300 Million Years of HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Stonehenge Notes and TheoriesDocument7 pagesStonehenge Notes and TheoriesLily Evans0% (2)

- Ibis - January 1959 - Grant - THE EXPEDITION OF THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS UNION TO NEW GUINEA 1909 1911 PDFDocument6 pagesIbis - January 1959 - Grant - THE EXPEDITION OF THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS UNION TO NEW GUINEA 1909 1911 PDFCaroli LilletiasNo ratings yet

- The England Coast Path 2nd edition: 1,100 Mini Adventures Around the World's Longest Coastal PathFrom EverandThe England Coast Path 2nd edition: 1,100 Mini Adventures Around the World's Longest Coastal PathNo ratings yet

- Vancouver GeologyDocument129 pagesVancouver GeologyBill LeeNo ratings yet

- September Newsletter 2016Document4 pagesSeptember Newsletter 2016api-320216112No ratings yet

- Walking in the Peak District - White Peak East: 42 walks in Derbyshire including Bakewell, Matlock and Stoney MiddletonFrom EverandWalking in the Peak District - White Peak East: 42 walks in Derbyshire including Bakewell, Matlock and Stoney MiddletonNo ratings yet

- Vancouver GeologyDocument130 pagesVancouver GeologydesktopdropboxNo ratings yet

- Vancouver Island Exploration (Robert Brown)Document32 pagesVancouver Island Exploration (Robert Brown)Dave LangNo ratings yet

- First Two Pages of rcst3j20Document3 pagesFirst Two Pages of rcst3j20api-98783757No ratings yet

- Remembering the victims of BanqiaoDocument8 pagesRemembering the victims of BanqiaoRuth Vargas SosaNo ratings yet

- Snow White and The HuntsmanDocument3 pagesSnow White and The HuntsmanAlison WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Reading SummarizingDocument9 pagesReading Summarizingpo PoNo ratings yet

- Short Line To Paradise: The Story Of The Yosemite Valley RailroadFrom EverandShort Line To Paradise: The Story Of The Yosemite Valley RailroadNo ratings yet

- Heart of The Arctic 2016Document10 pagesHeart of The Arctic 2016adventurecanadaNo ratings yet

- 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea: Jules VerneDocument280 pages20,000 Leagues Under The Sea: Jules VerneJoshua Michael Taylor MieritzNo ratings yet

- Raising The Mary Rose: How A Sixteenth-Century Warship Was Recovered From The SeabedDocument3 pagesRaising The Mary Rose: How A Sixteenth-Century Warship Was Recovered From The SeabedOrfat ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Stonehenge ThesisDocument5 pagesStonehenge Thesisjenniferriveraerie100% (2)

- Walking the Dartmoor Way: 109-mile hike around Dartmoor National ParkFrom EverandWalking the Dartmoor Way: 109-mile hike around Dartmoor National ParkNo ratings yet

- CAM 16 Test 04Document11 pagesCAM 16 Test 04Trương Khiết AnhNo ratings yet

- Fallen Tree Trunk, Appx. 200 000 B.C.E.: Anywhere in The WorldDocument22 pagesFallen Tree Trunk, Appx. 200 000 B.C.E.: Anywhere in The WorldIlciNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Man: A History of Melville Koppies in Veld & Flora 98Document2 pagesThe Nature of Man: A History of Melville Koppies in Veld & Flora 98veldfloraedNo ratings yet

- The Peddars Way and Norfolk Coast Path: 130 mile national trail - Norfolk's best inland and coastal sceneryFrom EverandThe Peddars Way and Norfolk Coast Path: 130 mile national trail - Norfolk's best inland and coastal sceneryNo ratings yet

- Class 11 CCTDocument3 pagesClass 11 CCTChanduNo ratings yet

- Arctic48 4 391Document2 pagesArctic48 4 391NunatsiaqNewsNo ratings yet

- The West is Calling: Imagining British ColumbiaFrom EverandThe West is Calling: Imagining British ColumbiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Britains Best CanalsDocument6 pagesBritains Best CanalsRaviNo ratings yet

- Now You Know Disasters: The Little Book of AnswersFrom EverandNow You Know Disasters: The Little Book of AnswersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Quaternary Events at Craig Rhosyfelin, PembrokeshireDocument18 pagesQuaternary Events at Craig Rhosyfelin, PembrokeshireBrian JohnNo ratings yet

- A Long History of Rhosyfelin (4th Version)Document22 pagesA Long History of Rhosyfelin (4th Version)Brian JohnNo ratings yet

- The Restless Northwest: A Geological StoryFrom EverandThe Restless Northwest: A Geological StoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- A Long History of Rhosyfelin (4th Version)Document22 pagesA Long History of Rhosyfelin (4th Version)Brian JohnNo ratings yet

- Our Caughnawagas in Egypt a narrative of what was seen and accomplished by the contingent of North American Indian voyageurs who led the British boat Expedition for the Relief of Khartoum up the Cataracts of the Nile.From EverandOur Caughnawagas in Egypt a narrative of what was seen and accomplished by the contingent of North American Indian voyageurs who led the British boat Expedition for the Relief of Khartoum up the Cataracts of the Nile.No ratings yet

- A Long History of Rhosyfelin (Revised)Document22 pagesA Long History of Rhosyfelin (Revised)Brian JohnNo ratings yet

- A Long History of RhosyfelinDocument19 pagesA Long History of RhosyfelinBrian John100% (1)

- Emergency Evacuation of Offshore InstallationDocument15 pagesEmergency Evacuation of Offshore Installationidhur61No ratings yet

- Bohai 2 Oil Rig AccidentDocument3 pagesBohai 2 Oil Rig Accidentnick100% (1)

- Local Disaster Risk Reduction PlansDocument2 pagesLocal Disaster Risk Reduction PlansGandarra Keviana Filipa100% (1)

- The Thing II Treatment)Document7 pagesThe Thing II Treatment)Sagui CohenNo ratings yet

- Into the Mist: The Story of the Empress of IrelandFrom EverandInto the Mist: The Story of the Empress of IrelandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- MOB-TSS &fogDocument3 pagesMOB-TSS &fogVijay VasittiNo ratings yet

- The Delaware and Hudson Canal and the Gravity RailroadFrom EverandThe Delaware and Hudson Canal and the Gravity RailroadNo ratings yet

- LFI - S7000 Incident During The Pemex Power Generation Platform ProjectDocument27 pagesLFI - S7000 Incident During The Pemex Power Generation Platform Projectacmilan4eva1899No ratings yet

- The Story of the Malverns - With Appendices and IllustrationsFrom EverandThe Story of the Malverns - With Appendices and IllustrationsNo ratings yet

- 201203-RCG Towards A Predictable Model-FINALDocument158 pages201203-RCG Towards A Predictable Model-FINALHendra WijayaNo ratings yet

- Alkhidmat Foundation Pakistan - AchievmentsDocument56 pagesAlkhidmat Foundation Pakistan - AchievmentsMuhammadNaeemSafdarChapNo ratings yet

- Providing Shelters To Survivors of Super Typhoon Haiyan in Molocaboc Island, Sagay City, Negros OccidentalDocument3 pagesProviding Shelters To Survivors of Super Typhoon Haiyan in Molocaboc Island, Sagay City, Negros Occidentalcarlos-tulali-1309No ratings yet

- Us Army North Conplan 3501 3502 11. FinalDocument14 pagesUs Army North Conplan 3501 3502 11. FinalPATRIOTSKULLZNo ratings yet

- Us & R Task Force - FemaDocument85 pagesUs & R Task Force - Femagsekar74No ratings yet

- Amazing Stories: Joan AcostaDocument35 pagesAmazing Stories: Joan AcostaEdén Verde Educación Con SaludNo ratings yet

- Quantity of LSA On Board The Cargo VesselDocument3 pagesQuantity of LSA On Board The Cargo VesselMihail KolishNo ratings yet

- Search and RescueDocument18 pagesSearch and RescueAbu NawshadNo ratings yet

- MartinA CallaghanDocument2 pagesMartinA CallaghanpresbaNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of HUckleberry FInn. Project in EngDocument4 pagesThe Adventures of HUckleberry FInn. Project in EngSean Joshua CarilloNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: Past ContinuousDocument15 pagesUnit 4: Past ContinuousmisheeltNo ratings yet

- Grammar & Usage Grammar & UsageDocument13 pagesGrammar & Usage Grammar & UsageJimmyNo ratings yet

- Creating A Dystopia WorksheetsDocument4 pagesCreating A Dystopia Worksheetsapi-2656941380% (1)

- Bacsil WrittenReportDocument40 pagesBacsil WrittenReportMikeKarlDiazMarzanNo ratings yet

- Sample Radio Medical Advice (RMA)Document26 pagesSample Radio Medical Advice (RMA)Anna Kathrina RoblesNo ratings yet

- Select Homeland Security Purchases in IowaDocument3 pagesSelect Homeland Security Purchases in IowaGazetteonlineNo ratings yet

- Water Rescue PDFDocument68 pagesWater Rescue PDFRachmat Wihandana AgasiNo ratings yet

- SCDF Annual Report 2011Document64 pagesSCDF Annual Report 2011davidwongbxNo ratings yet

- MFR Nara - t8 - FBI - FBI Wfo Brief On Pentagon - 8-5-03 - 00268Document5 pagesMFR Nara - t8 - FBI - FBI Wfo Brief On Pentagon - 8-5-03 - 002689/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- United States Coast GuardDocument28 pagesUnited States Coast GuardPoliceUSA100% (1)

- Disaster Communication Plan for Barangay PaasaDocument3 pagesDisaster Communication Plan for Barangay PaasaMarcos Dmitri100% (1)

- AMSA36Document66 pagesAMSA36Btwins123100% (2)

- Fire Brigade Organizational StructureDocument13 pagesFire Brigade Organizational StructureHOney Maban MakilangNo ratings yet

- Character Guide to Spenser's Faerie QueeneDocument4 pagesCharacter Guide to Spenser's Faerie QueenePhilip CoalesNo ratings yet

- The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of ClutterFrom EverandThe Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of ClutterRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (467)

- Plant Based Sauces and Dips Recipes: Beginner’s Cookbook to Healthy Plant-Based EatingFrom EverandPlant Based Sauces and Dips Recipes: Beginner’s Cookbook to Healthy Plant-Based EatingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeFrom EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3224)

- The Encyclopedia of Spices & Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the WorldFrom EverandThe Encyclopedia of Spices & Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Survival Mom: How to Prepare Your Family for Everyday Disasters and Worst-Case ScenariosFrom EverandSurvival Mom: How to Prepare Your Family for Everyday Disasters and Worst-Case ScenariosRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the UniverseFrom EverandAristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the UniverseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2341)

- The Martha Manual: How to Do (Almost) EverythingFrom EverandThe Martha Manual: How to Do (Almost) EverythingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- How To Win Friends And Influence PeopleFrom EverandHow To Win Friends And Influence PeopleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6510)

- Crochet Impkins: Over a million possible combinations! Yes, really!From EverandCrochet Impkins: Over a million possible combinations! Yes, really!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Root to Leaf: A Southern Chef Cooks Through the SeasonsFrom EverandRoot to Leaf: A Southern Chef Cooks Through the SeasonsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)