Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Displaced Architecture

Uploaded by

rb21660 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views4 pagesarchitecture

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentarchitecture

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views4 pagesDisplaced Architecture

Uploaded by

rb2166architecture

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

1

Lost / Displaced Architecture

Dr. Wagih Fawzi Youssef

/.

July 2013

Abstract

This essay argues that an architecture that merely focuses on style, individual or historic, needs to redirect

the focus to a contextual architecture that is sensitized to social, cultural and economic needs. Importantly,

such a shift in focus may not be evident nor easy to maintain given that architecture is constituted of several

dilemmas: a dilemma of style, a dilemma of ethnocentricity, a dilemma of non-linearity, a dilemma of change,

and a dilemma of diversity.

Keywords: architectural style, displaced architecture, ethnocentricity, change and diversity.

Introduction

Architecture was never created in a social, or economic, or religious, void. Rather, architecture was created,

and originated, in response to the needs of society. Many architectural appraisers and critics have merely

discussed questions related, from near and far, to social and historical issues such as why a particular style

of building at a particular time appealed to particular people. What has been overlooked by critics is that

preference for a particular style is likely to lessen ones ability to appreciate other styles and thus render other

styles, so to speak, impalpable.

Similarly, the appraisal of architecture as the highest form of fne arts risks the possibility of it being reduced to

a sculpture or art form. For Ruskin, there are only two possible fne arts accessible to the human race: sculpture

and painting. Accordingly, what we call architecture is only the association of sculpture and painting in noble

masses, or the placing of them in ft places. Le Corbusier proclaimed in his own dogmatic fashion that styles

were a lie. Schopenhauer remarked that architecture, to the extent that it fulflls practical purposes, cannot be

called art because serving utility entails attending to the will, i.e. to material needs rather than pure cognition.

This essay purposes to shift architectural and art critics preoccupation with style towards a contextual

architecture that is geared towards addressing socio-economic and socio-cultural needs. It argues that the drift

contemporary architecture is currently undergoing and which could be better described as lost or displaced

architecture needs to be stemmed and re-directed towards a socially constructive architecture.

The dilemma of Architecture

Architects seem to have no faith in a defnite system of rules but are propelled, and commonly sabotaged,

by the rule of astonishing. The architect submits to a tension between stability and change, between the

production of existing forms and the invention of new ones. It is a submission by necessity and not by choice;

for when change is not prompted by inventiveness, it is prompted by boredom. Conversely, the architect

cannot invent without reproducing. In order to make a meaningful innovation, he must concentrate his creative

force upon a few aspects of his work that favor fresh departures. For the remaining aspects, he relies on the

support of his tradition and of his environment. Indeed, an architect cannot invent himself out of his time and

if he ever could, he would succeed only in making his work incomprehensible by abandoning the framework

in which it might have been understood.

2

Style

Flexibility causes radical shifts of style in the course of a generation. Whereas in ancient Egypt for instance,

stability predominated to the point that barely perceptible innovations were suffcient to secure the vitality of

a style for three millennia. Change and stability are primeval forces determining style and cannot be invested

with value except in terms of some preconceived image of mans destiny.

If style must exhibit some stability and fexibility then all of its possible characteristics cannot contribute

in equal measure. Conventions of form and of symbolism yield the richest harvest of traits by which to

distinguish style. We form an image of the style of an individual by observing the interaction of his private

conventions and the public conventions of his time and place. I mean by conventions an accepted vocabulary

of elements such as scale, an architectural order and a syntax by which these elements are composed into

his building, or otherwise. One of the most persistent challenges of architectural history is to explain the

motivations, behavior, and pace of change in style.

Ethnocentricity

We are ethnocentric in the sense that we act, think and evaluate inside the decorum of our culture, inside a

pattern to which the tacitly implied rules in the work of architecture belong. Changes of decorum depend upon

time and cultural milieu, age, temperament, education and class. There are two main types of ethnocentricity.

There is an ethnocentricity in time from the point of view that one epoch has a value system different from

those of other times. There is an ethnocentricity in geography from the point of view that different cultures at

a particular time will have different value-systems.

We cannot erase our established image of the totality of a style whose process of formation occurred in the

past. Nonetheless, this should not discourage us from trying to interpret a work of architecture in terms of its

proper context rather than its effects. This could be made possible by gaining perspective within the process

at points short of its termination. At any one of these points, we could fnd an architect designing a religious

institution, for instance, a mosque. He, too, is aware of works preceding his, and of designs being made by

his contemporaries. Such precedents constitute an important resource in the formation of his style, but he is

not aware of the designs which follow his. He knows only past and present. He accepts and rejects aspects of

what he fnds in things about him and he adds something of his own.

By his choice and by his contribution, he moves a step away from the past. Are we then justifed in saying that

he has moved toward the future? From his vantage point, the future is a void. He may happen to contribute to

the future, but only by having concentrated all his powers on the making of something intrinsically worthwhile

in the present. Architects communicate experiences rather than expectations. Anyone who seeks to alter or to

accelerate the change of style in the hope of anticipating the future is likely to become like a fashion designer,

an expert in and purveyor of taste.

Non-linearity and Architectural Impedance

What we call evolution in architecture should not be described as a succession of steps towards a solution to

a given problem. We cannot speak properly of a sequence of solutions to a given problem since, with each

solution, the nature of the problem changes. The pattern of change is a product of the tension in society, and

in the architect, between the instinct of stability / security of established schemes and human capacity resulting

partly from biological and psychological differences for creating something unique and individualized. Change

is slow when the former is stronger, rapid when the latter prevails. As a rule, the factor of stability gets more

support from society and its institutions while the factor of change from the individual imagination. Notice

that creative vision is seldom granted to groups!!

Given this background, it is necessary to emphasize that a nation is a religion to resist, rather than promote,

change in style. Nations show a tendency to keep certain kinds of innovation and to cast out other kinds. It is

3

by this conservative post facto pressure that society affects architecture. Indeed, the demands of a society and

the inclinations of architects make the innovations of the latest work by contemporaries in the same culture

expressly interesting because they represent attempts to solve, in a familiar language, the kind of problem

which is most challenging at the moment. But the creative process is complex enough to be stimulated at

many points. Often, the architecture of earlier times or foreign places offers solutions to such problems, too.

Form as a generative and individual process

So, inspirations may come from far as from near. Sometimes, especially in the formation of new problems,

an architect may experience and put to use, in making a work of architecture, anything in his environment.

The historian must reconstruct as much of that environment as possible. Each work of architecture can be

considered a repository of experiences in the architects surroundings. This is so much so that it owes a special

debt to great predecessors of the same tradition.

Change in style is a manifestation rather of the imagination of an individual architect than of historical forces

that guide the actions of men and nations. An architectural idea is often said to exercise a shaping infuence

on the particular form in which it occurs. This concept of form as a generative process has became axiomatic

in most writing about form, the initial force of a composition in the invention of some defnite theme. Specifc

generative tendencies are inherent in the nature of a particular idea.

The form of works of architecture varies with the qualities of the material in which they are executed. If they

are executed in steel, or wood, or stone, they must necessarily differ in form in accordance with the inherent

properties of the materials. Forms arise from the inner nature of these materials. Why does a particular

idea tend to generate a particular form or at least a certain type of form? In what sense is the unfolding of

that form inherent in the idea? Form obviously has some functional relation to the materials. The kernel of

development, unfortunately, almost unexplained.

Change, Unity and Variety

In any case, however, little may actually be explained in words. That little must surely have the utmost bearing

on the interdependence of form and style; an interdependence that constitutes one of the most neglected

problems in architectural history.

One such principle, not fully explained in words, is the familiar requirement of form in every design to achieve

variety within unity. It is important to iterate that a basic means of achieving unity in architecture is by

repetition of primary material; meanwhile, a basic means of achieving variety is by contrasting a subordinate

material to the primary material.

Alternatively, a space is perceived initially as a whole, and only afterwards in more detail, remaining all the

while in view. When the theory of organic unity claims that any inadvertent subtraction or addition would

diminish the value of the work of architecture as a whole while also changing the character of all the contained

parts, it does not necessarily follow that every part is equally important, in terms of prominence or impact.

Does anyone hold as factual that any subtraction or addition changes the character of all the contained parts of

a work of architecture when referring to the ancient law of organic unity as the master principle of aesthetic

form?

By organic unity we mean the fact that each element in a work of architecture is necessary to its value, that it

contains no elements that are thus not necessary and that all needful elements are there. The concept of unity

is allied to the idea of art or skill, whereas the concept of variety is allied to the idea of creativity or genius.

Maximum unity tends to curtail variety. Many of the weakness in present day design can be traced to inhibitions

which derive from erroneous assumptions about human behavior. A clearer and more scientifc understanding

of people should help liberate architecture from these inhibitions and give rise to buildings which are more

satisfying for their users.

4

It has been assumed that psychology has a very broad relevance for architects. The environment they

manipulate has been taken to cover as wide a perspective as possible including spatial and visual aspects as

well as lighting or acoustic levels. For if human behavior is so erratic or unpredictable that it is impossible to

fnd principles which underlay it, or discover trends within it, then it would never be possible for one person to

produce buildings for others to use because he would never know what to expect of the users nor they of him.

The problem is that many people do not seem to think as highly of buildings as the design professions do

themselves. More often than not, people had quite different conceptions of what the buildings were meant to

be. One group is probably concerned with judgments people had made of what it looked like, the other group

with the actual effects of buildings on what people did.

Most architects are constantly involved in what a building looks like. In effect, this means that they are trying

to create a physical form which will be perceived in a particular set of ways. Many buildings, however, seem

to be designed as if the users come to them with a standard set of reactions which remain throughout their

contact with the building.

Designers do not agree on what is the precise nature of the design process. Designers understand that designing

is a decision-making process in the face of uncertainty with high penalties in case of error. Notably, there are

limits to the range of change with which a person can cope without suffering psychological breakdown. Some

designers have fallen into some traps when using a set of inappropriate social values as the basis for their

designs. Designers must consider not only the problem-solving aspect but also the context of the design itself

in order to see if that might tolerate design intervention. Designers must also have an awareness of the real

world and a feeling of accountability for the consequences of failure in design.

Diversity or Disunity

The characteristic most expressive of the contemporary architectural scene is diversity. Unfortunately, in

response to those architects who regard signifcance in architecture as a corollary of order, the diversity

approach to architectural problems is producing chaos in our city spaces. The internal world of our thoughts

has become divided and the result has been a lack of unity in our lives.

The architects of this century have produced numerous brilliant individual structures, but this has been at the

expense of the unity, harmony and scale that are fundamental to a civilized and healthy environment. In search

for the new, it is easy to overlook the limited role that isolated buildings in the city can assume. The architect

must attempt to bring diversity into a harmonious and viable unity with the intention to preserve while not

allowing diversity to freewheel into chaos. It is a delicate, yet vital balance. Chaos comes from uncertainty

and indecision; convictions are the prelude order for unity.

Conclusion

Art and science have been pursuing diverse paths and architecture was left adrift. The result was a period

of reaction from the most important facts of the time. Eclecticism produced an architecture detached from

the reality of the pressures of the industrial revolution. What architecture needed was not a nostalgia for the

past however beautifully executed, but the utilization of industrys new potential in order to tackle its own

particular problems.

Architects are exploiting the futuristic potential contained within buildings by turning actuality and

progressiveness into stylistic features. The new virtual reality is imitated and adapted in contemporary

architecture, with science fction, imaginative backdrops and an expressive range which extends from

deconstruction to digitalism; designs intended to dramatize the world and blur the border between walking

reality and the dream state.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Case For SpaceDocument51 pagesCase For Spacerb2166100% (2)

- EcoVillage at Ithaca Pioneering A Sustainable CultureDocument257 pagesEcoVillage at Ithaca Pioneering A Sustainable Cultureshature100% (2)

- Making Western Agriculture More SustainableDocument21 pagesMaking Western Agriculture More Sustainablerb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black Theses On Groucho Marxism A4Document4 pagesBob Black Theses On Groucho Marxism A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Agroforestry in Sustainable Agricultural SystemsDocument411 pagesAgroforestry in Sustainable Agricultural Systemsrb2166100% (2)

- Bob Black Primitive Affluence A Postscript To Sahlins A4Document8 pagesBob Black Primitive Affluence A Postscript To Sahlins A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black The Libertarian As Conservative A4Document7 pagesBob Black The Libertarian As Conservative A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black The Anti-Anarchist Conspiracy An Empirical Test A4Document6 pagesBob Black The Anti-Anarchist Conspiracy An Empirical Test A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black Theses On Anarchism After Post-Modernism A4Document5 pagesBob Black Theses On Anarchism After Post-Modernism A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black Feminism As Fascism A4Document6 pagesBob Black Feminism As Fascism A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black Technophilia An Infantile Disorder A4Document9 pagesBob Black Technophilia An Infantile Disorder A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Bob Black Quit While You Re Ahead A4Document6 pagesBob Black Quit While You Re Ahead A4rb2166No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Med2 PC Building Uk HR PDFDocument1 pageMed2 PC Building Uk HR PDFfiorenzorNo ratings yet

- Public Lighting GuidelinesDocument25 pagesPublic Lighting Guidelinesdiksha_vaid17232No ratings yet

- ThinkPad E470 SpecsDocument1 pageThinkPad E470 Specsmuhammad tirta agustaNo ratings yet

- COnreteDocument25 pagesCOnretehbNo ratings yet

- DocxDocument11 pagesDocxKennedy Gitonga ArithiNo ratings yet

- CryptocurrencyDocument35 pagesCryptocurrencyGokul DineshNo ratings yet

- RS232 and Hyper Terminal Basics by ARLDocument9 pagesRS232 and Hyper Terminal Basics by ARLarl2703No ratings yet

- 3rd Party Database enDocument10 pages3rd Party Database ennonene8048No ratings yet

- Ceramic Tile InstallationDocument4 pagesCeramic Tile InstallationAjit Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- LPCG Sections 1-3 PDFDocument154 pagesLPCG Sections 1-3 PDFAxyNo ratings yet

- Hardox I WeldoxDocument6 pagesHardox I Weldoxbosnamontaza5869No ratings yet

- Radio Link Supervision in LTEDocument65 pagesRadio Link Supervision in LTEFathy Farouk100% (3)

- Lightolier Calculite and Lytecaster Incandescent Downlight Catalog 1978Document94 pagesLightolier Calculite and Lytecaster Incandescent Downlight Catalog 1978Alan Masters100% (1)

- Courtney Love Science 101 Electricity and HeatDocument41 pagesCourtney Love Science 101 Electricity and HeatCourtney Love Arriedo OridoNo ratings yet

- NL Master Specification Guide For Public Funded Buildings: Re-Issued 2020/08/28Document8 pagesNL Master Specification Guide For Public Funded Buildings: Re-Issued 2020/08/28Shamim Ahsan ZuberyNo ratings yet

- How To Configure VIO LUNs From SAN To Client LPARsDocument9 pagesHow To Configure VIO LUNs From SAN To Client LPARsTirumala RaoNo ratings yet

- Cabinet EstimateDocument2 pagesCabinet EstimateJames WhiteNo ratings yet

- Star Schema ArchitectureDocument1 pageStar Schema ArchitectureKarthik RaparthyNo ratings yet

- OPNET Model LibraryDocument4 pagesOPNET Model LibraryRodrigo Zapata100% (1)

- HW 076443Document64 pagesHW 076443حيدر قاسم احمدNo ratings yet

- Law On Spatial Development and Contruction July 2011Document52 pagesLaw On Spatial Development and Contruction July 2011mikivukcevicNo ratings yet

- 26mdo007 Ao l5#M-06 Integrated#26mdo007 Ao L5-Piere Tendean-new-done-3may2019-Thomy SatriaDocument237 pages26mdo007 Ao l5#M-06 Integrated#26mdo007 Ao L5-Piere Tendean-new-done-3may2019-Thomy SatriaTasya Tobing0% (1)

- Cellular MobDocument936 pagesCellular MobchandanaNo ratings yet

- 3com NBX V3000 Admin GuideDocument482 pages3com NBX V3000 Admin GuideshemuzNo ratings yet

- Architect Agreement Contract 2 PDFDocument5 pagesArchitect Agreement Contract 2 PDFS Lakhte Haider ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Classification of ComputersDocument2 pagesClassification of Computerseduardo acuniaNo ratings yet

- D08 - Best Practices For Upgrading To DB2 9.7 (With Notes)Document59 pagesD08 - Best Practices For Upgrading To DB2 9.7 (With Notes)CKEITH14No ratings yet

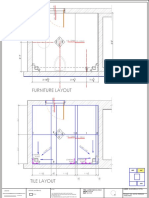

- Goyal Terrace - A61 - Toilet Layouts - 20-12-2022 - Rutuja PDFDocument6 pagesGoyal Terrace - A61 - Toilet Layouts - 20-12-2022 - Rutuja PDFRutuja RajurwarNo ratings yet

- StudentsDocument7 pagesStudentsBhautik DaxiniNo ratings yet

- SCOPE+OF+ACCREDITATION (Construction+Materials+Testing) DCL TestingDocument34 pagesSCOPE+OF+ACCREDITATION (Construction+Materials+Testing) DCL TestingGhayas JawedNo ratings yet