Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Migraine Prophylaxis: Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

Uploaded by

jo_jo_maniaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Migraine Prophylaxis: Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

Uploaded by

jo_jo_maniaCopyright:

Available Formats

Berikut ini adalah versi HTML dari berkas http://www.pswi.org/professional/pharmaco/migraine.pdf.

G o o g l e membuat versi HTML dari dokumen tersebut secara otomatis pada saat menelusuri web.

Page 1

Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

20 Nov/Dec 2000 Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin

Migraine Prophylaxis

Principles, goals and drug therapy

by Sarah E. Bland, RPh

Column Editor: Lee Vermeulen, MS, RPh,

Director, Center for Drug Policy, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics

The information given and views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of PSW, its Board or members.

Goals of treatment

According to the University of Wisconsin Hospital and

Clinics Migraine Treatment Guideline, the goals of treatment

are to reduce the frequency and severity of migraine attacks; a

secondary goal may include improving the responsiveness of

attacks to abortive therapy.7 A good response may be defined

as a 50% reduction in the frequency or severity of the attacks.

The lowest effective dose of medication should be used in

order to minimize side effects. Patients should not expect that

they will become completely free of migraines; rather, they

should expect that they will have less disability. Rescue

medications should still be available to the patient.

Non-pharmacologic measures

All prophylactic treatment plans should include some non-

pharmacologic treatment strategies intended to reduce the

patients exposure to triggers that may cause a migraine attack

to start. Common triggers are missed meals; too little sleep;

excessive heat and humidity; certain foods such as chocolate,

hard cheeses, alcoholic beverages, citrus fruits, nuts, excessive

caffeine, and caffeine withdrawal; medication such as oral

contraceptives, overuse of analgesics, sympathomimetic street

drugs; strong sensory stimuli such as bright lights, glare,

flickering lights, odors, smoke and prolonged exposure to heat

or cold. Patients should be encouraged to keep a headache diary

in an effort to identify triggers.

Introduction

Migraine headache is a chronic condition characterized by

repeated, debilitating attacks of severe, usually unilateral,

pulsatile headaches, often accompanied by nausea, vomiting,

photophobia and a variety of other symptoms. Classical mi-

graine is associated with prodromal symptoms referred to as

aura; common migraine usually lacks these prodromal symp-

toms. It is a disorder with a prevalence of 17.6% in American

females and 5.7% in American males.1 The prevalence of

migraine begins to increase starting at age 12, peaks at about

age 38, and declines thereafter. It is approximately twice as

common in boys as in girls at age 12, becomes 3.3 times as

common in women as men between the ages of 42-44 and

decreases to 2.5 times as common in women by age 70.2

Although there is a common misperception that migraine is

more common in those who have the time and money to seek

treatment, the American Migraine Study has provided docu-

mentation that its incidence actually decreases with higher

socioeconomic status.1

Among the respondents to the American Migraine Study,

25% of the women had four or more severe attacks monthly,

35% had three severe attacks monthly and 40% had one severe

attack per month or less.1 The male respondents reported a

similar frequency of attacks. Over 80% of respondents re-

ported at least some degree of disability with their headaches,

including severe disability or the need for bed rest in one-

fourth of cases. Despite the degree of disability reported, 57%

of males and 68% of females had never consulted a physician

for their headaches.4 Of those who consulted with physicians,

42% reported that they had not received a diagnosis of mi-

graine. Only 13.6% of female migraineurs and 10.4% of males

consulted with a neurologist about their headaches; fewer still,

1.6% of females and 4.7% males, consulted with a pain or

headache specialist.

While the degree of disability experienced by migraineurs

varies widely from patient to patient5, efforts have been made

to estimate the cost of the disability resulting from migraine.

A recently published study estimated that each year in the

United States, 112 million workdays are missed and $13

billion are lost to employers due to absenteeism and reduced

productivity.6 There are also losses experienced in the social

aspects of life that have no means of measurement.

The recent studies of migraine have shown that it is a

common problem, afflicting over 10 million Americans at a

high social and economic cost. At the same time, it appears to

be a medical problem for which patients often do not seek help,

and when they do, the diagnosis is often missed and referrals

to specialists are infrequent. This is unfortunate, because there

are many effective, well-tolerated methods available for the

prevention and treatment of migraine. This article will address

the principles and goals of migraine prophylaxis. The primary

reference for the recommendations made here is the UW

Hospital and Clinics Migraine Assessment and Treatment

Guideline.7

Page 2

Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin Nov/Dec 2000 21

Indications for pharmacologic prophylaxis

Any one of the following indications is sufficient to war-

rant a trial of prophylactic medications.7-9 Some published

guidelines may recommend a minimum threshold number of

attacks per month, but such thresholds are in fact arbitrary and

any patient who wishes to reduce the number or intensity of

attacks should be considered as a candidate for prophylactic

therapy.

1. Occurrence of 2-3 attacks/month OR recurring attacks

that patients feel are interfering with their daily ac-

tivities even with acute treatment

2. Attacks lasting 48 hours or more

3. Extreme headache severity or prolonged aura

4. Presence of uncommon migraine conditions such as

hemiplegic migraine, basilar migraine, or migrainous

infarction

5. Inadequate relief from or overuse of acute therapies

6. Contraindication to or intolerable adverse effects

from acute therapies

7. Intolerable cost of acute therapies

8. Patient demand

Guiding principles of drug therapy

There are a number of helpful principles that can be used to

maximize the likelihood of successful results in migraine

prophylaxis.7,8,10 Careful consideration of these principles can

be useful in selecting the appropriate drug with which to begin

a prophylactic trial. Additionally, it is important to explain the

principles relating to commitment, compliance, trial duration

and elimination of confounding medications to patients so they

are able to participate fully in the process. Their input is

essential to successful prophylaxis.

1. Recognize that a plan of prophylactic therapy requires a

major commitment on the part of the patient and the

physician.

2. Educate patients about the importance of compliance.

Once an effective dose is determined, use of a long-

acting, once-daily dosage form may encourage compli-

ance.

3. Give each medication an adequate trial of two to three

months before evaluating its efficacy.

4. Reduce or eliminate the use of medications that exacer-

bate migraine or interfere or interact with the prophylac-

tic drug.

5. Use the lowest effective dose. Start with a very low dose

of the selected medication and titrate upward until a

satisfactory benefit is obtained without side effects or

until the dosage is limited by side effects. The doses

required to effectively treat migraine are often lower

than the doses required to treat other conditions such as

epilepsy, hypertension or depression.

6. While many patients may require combinations of drugs

for effective prophylaxis, it is important to add the drugs

one at a time in order to keep track of their respective

efficacies and to sort out side effect profiles.

7. Consider comorbid conditions when choosing a prophy-

lactic agent. For example, in a patient with hypertension,

it may be possible to choose drugs like beta-blockers or

verapamil that will control hypertension and also reduce

migraine recurrence. Choice of a multifunctional agent

can decrease possible adverse effects, increase compli-

ance and improve cost-effectiveness of therapy. Avoid

medications that could compromise patient care, like

beta-blockers in patients with asthma.

8. Consider also the side effect profile of the prophylactic

drugs and whether some of the side effects might be

beneficial in some patients. For example, the drowsi-

ness caused by the tricyclic antidepressants might be a

beneficial side effect in a patient who is also suffering

from insomnia.

Migraine guidelines

The University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics has

developed a Migraine Prophylaxis Guideline (on next page)

based on drugs that have proven efficacy for this indication.7

The guideline is arranged by drug class, with drugs within that

class listed in the second column. Minimum and maximum

dosages are recommended, and contraindications and com-

ments for each drug are included in the third column. The

section immediately following the guideline outlines the clini-

cal evidence for efficacy of each agent listed in the guideline.

Clinical evidence for efficacy

Propranolol has been demonstrated in a number of clinical

trials to be significantly more effective than placebo in reduc-

ing the number of migraine attacks.11-14 In addition, it has been

reported as effective in case series.15,16 Typical doses range

from 80 mg/day up to 320 mg/day. Good results were obtained

with the long-acting formulation which is convenient for

patients, and the drug was well-tolerated by most patients.

Other beta-blockers have been studied for migraine pro-

phylaxis. Metoprolol, in doses of 100-200 mg/day, was signifi-

cantly better than placebo in reducing the number of attacks

and number of migraine days, although its effect on pain

severity scores and analgesic tablet consumption was signifi-

cant only at the higher dose.17,18 Metoprolol has been directly

compared to propranolol in double-blind, cross-over studies;

100-200 mg/day of metoprolol was found to be as effective as

80 mg/day of propranolol in reducing headache frequency,

Page 3

Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

22 Nov/Dec 2000 Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin

migraine days, analgesic consumption and ergotamine con-

sumption.19,20 In the Olsson study, 100 mg metoprolol/day was

effective in reducing headache pain severity scores statisti-

cally significantly from baseline.

Atenolol was evaluated in a small trial of 24 patients in a

double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study.21 Doses of

100 mg/day were significantly better than placebo in reducing

migraine frequency and in its effect on headache overall.

Eleven of 20 patients included in the final analysis had a 50%

reduction in headache severity and two patients had no head-

aches during the study period while on atenolol.

A fourth beta-blocker that has been studied for migraine

Beta Blockers

Propranolol 40-240 mg/day PO

Atenolol 50-150 mg/day PO

Metoprolol 100-200 mg/day PO

Nadolol 20-60 mg/day PO

Propranolol and nadolol are contraindicated in bronchial asthma or

COPD

All beta-blockers are contraindicated in overt cardiac failure, 2nd or 3rd

degree AV block or severe sinus bradycardia

Caution in CHF, diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism/thyrotoxicosis, pe-

ripheral vascular disease

Do not withdraw abruptly; taper over 1-2 weeks

UWHC Migraine Prophylaxis Recommendations

Drug Class

Drug/Dose

Contraindications/Comments

Calcium Channel

Blockers

Verapamil 240-320 mg/day PO

Diltiazem 90-360 mg/day PO

Nimodipine 120-360 mg/day PO

Diltiazem and verapamil are contraindicated with atrial fibrillation or

flutter, accessory bypass tracts, short PR syndromes, hypotension (<90

mm Hg systolic), 2nd or 3rd degree AV block without functioning artificial

pacemaker, sick sinus syndrome, wide-complex ventricular tachycardia

(QRS>0.12)

Verapamil is contraindicated in CHF, digital ischemia, ulceration or

gangrene, idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, severe left ventricu-

lar dysfunction

Diltiazem and verapamil are contraindicated with impaired renal function

Avoid extended-release dosage forms of diltiazem and verapamil with GI

hypermotility or GI obstruction

Serotonin Receptor

Antagonists

Methysergide 2 mg every night,

gradually increased to TID (maximum

8 mg/day if needed); usual dose is 4-8

mg/day

Contraindicated in pregnancy, peripheral vascular or coronary artery

disease, lower limb phlebitis, pulmonary disease, collagen diseases or

fibrotic disease, impaired liver or renal function or valvular disease;

drug holidays of 3-4 weeks every 6 months are needed to prevent

serious drug toxicity

Anti-epileptics

Tricyclic

Antidepressants

Amitriptyline 10-150 mg every night

Nortriptyline 10-150 mg every night

(start with 10 mg and increase as

tolerated until adequate response or

intolerable side effects)

TCAs are contraindicated in the acute recovery phase following myo-

cardial infarction, and with concomitant use of monamine oxidase

inhibitors (MAOIs)

Use with caution in seizure disorders; history of urinary retention,

glaucoma or increased ocular pressure; hyperthyroidism; schizophre-

nia and cardiovascular disease

Nortriptyline should not be used concomitantly with reserpine

Divalproex 500-1500 mg/day

Valproic acid 500-1500 mg/day

Valproic acid and divalproex are contraindicated in pregnancy or with

liver disease

Use with caution with drugs that affect platelet function, or with concomi-

tant use of other CNS depressants

prophylaxis is nadolol. In a study of 80 patients taking 0, 80,

160 or 240 mg/day, patients taking 160 or 240 mg/day had a

reduction in the frequency and severity of their migraines.22

Nadolol 80 and 160 mg/day have also been compared to

propranolol 160 mg/day in migraine prophylaxis.23,24 In the

Sudilovsky study, the higher dose of nadolol produced supe-

rior results to propranolol in headache frequency, intensity,

pain days and use of relief medications by the end of the first

month of treatment. In the Ryan study, the lower dose of

nadolol produced the greatest improvements but the difference

between the groups was not statistically significant.

Verapamil is a calcium channel blocker that has been used

Page 4

Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin Nov/Dec 2000 23

prophylactically for migraine, although there has been little

clinical study of it. A review of three double-blind clinical

trials indicates that verapamil, in doses of 240-320 mg/day, is

significantly more effective than placebo in preventing mi-

graine, with the 320 mg dose being more effective than the 240

mg dose.25 Forty-five percent of the 133 patients in the trials

reported greater than 50% improvement in migraine frequency.

Diltiazem has also been used successfully in migraine prophy-

laxis, although it, too, has been little studied.26

Nimodipine has been found to be superior to placebo in

migraine prevention in a double-blind, cross-over trial of 33

patients.27 Statistically significant improvements were attained

in headache frequency, duration and headache index (pain

severity X migraine days/28 days). Studies comparing

nimodipine to flunarizine and pizotifen as well as placebo

found nimodipine to be superior to placebo and equivalent in

efficacy to the comparator drugs.28,29 Two other studies have

shown a strong placebo response in addition to a good response

to nimodipine; a superior benefit from nimodipine could not be

established in these studies.30,31 The usual dose of nimodipine

administered in the studies was 40 mg three times daily.

A fourth calcium channel blocker, nifedipine, was com-

pared to propranolol for migraine prophylaxis.32 In this small,

open-label study, nifedipine was less effective than propra-

nolol and had a much higher incidence of side effects; 45% of

the 20 patients on nifedipine withdrew from the study within

two weeks. A second study found no difference between

nifedipine and placebo in the frequency of headaches, although

side effects were frequent among nifedipine users.33 Based on

the lack of significant benefit and the frequency of side effects,

nifedipine is generally not used for migraine prophylaxis.

Methysergide is a serotonin receptor antagonist that has

been used for migraine prophylaxis for many years. It has

unique and serious toxicities, however, that limit its use to the

most severe and refractory cases and require drug holidays of

3-4 weeks every six months. Its efficacy has been demon-

strated in several clinical trials.34-37 In the Pedersen trial, 60 of

102 patients completed the trial; 57% had a 50% response to

methysergide and methysergide was superior to placebo.34 In

the Whewell trial, 50 of 74 patients completed the trial.

Patients achieved a small decrease in the number of attacks, a

small decline in the duration of attacks and a larger decrease in

the duration of severe headaches.35 Use of methysergide re-

sulted in a statistically significant decline in the number of

attacks per week and in headache index in the Forssman trial;

decreases in duration and intensity were not statistically sig-

nificant.36 In the Lance trial, methysergide produced the best

results among six different serotonin antagonists including

cyproheptadine and methdilazine; 64% of patients on

methysergide had a 50% or greater improvement in their

headaches.37

Amitriptyline has been used widely and effectively for

migraine prophylaxis, although there are not many clinical

trials available. A placebo-controlled trial in 100 patients

found that amitriptyline in doses of up to 100 mg/day was more

effective than placebo in preventing migraine.38 Over 55% of

patients receiving amitriptyline had a 50% improvement in

their headaches, compared to 34% of patients taking placebo.

Amitriptyline was most effective in non-depressed patients

with severe migraine and depressed patients with less severe

migraine; depressed patients with severe migraine did not

respond as well. A second trial compared amitriptyline in

doses of 50 to 150 mg/day to propranolol 80 to 240 mg/day.39

Both drugs were superior to placebo and there was no differ-

ence in efficacy between them. Amitriptyline has been com-

pared to fluvoxamine for migraine prophylaxis in a study of 70

patients.40 Both drugs reduced the headache index to a statis-

tically significant degree. Drowsiness was more common

among patients receiving amitriptyline; a larger number of

patients taking amitriptyline dropped out of the study (9

compared with 2 for fluvoxamine). Nortriptyline is sometimes

used as an alternative to amitriptyline. It is often better toler-

ated than amitriptyline and it appears to be effective, but

clinical trials demonstrating its efficacy are lacking.

Divalproex sodium was evaluated for migraine prophy-

laxis in a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study.41 Patients

received either placebo, divalproex 500 mg/day, 1000 mg/day

or 1500 mg/day. The three treatment groups had statistically

significant improvements in headache frequency and severity,

although there was no significant difference among the doses

in degree of improvement. A second trial compared divalproex

sodium to placebo in 107 patients.42 Headache frequency and

severity were significantly decreased while patients were

taking divalproex. Side effects, mainly nausea and drowsiness,

were generally mild to moderate. There was no significant

difference between the treatment and placebo groups in the

number of patients withdrawing due to intolerance. A review

of studies of sodium valproate and divalproex sodium for

migraine and chronic daily headache found that patients im-

proved on these drugs in 10 of 11 studies.43 Doses from 500 to

2000 mg/day were evaluated and were well-tolerated.

Divalproex has become one of the mainstays in the treatment

of migraine, although its use is associated with the undesirable

side effect of weight gain. Patients should be counseled about

this effect and monitored for weight gain during treatment.

Emerging treatments

There are a number of drugs that are currently being used

for migraine prophylaxis that have scant published evidence

for efficacy or only anecdotal evidence. For most of these

drugs, there is not yet enough experience with them to offer

firm recommendations for dosing. However, their use may

prove beneficial in refractory patients and are mentioned here

Page 5

Pharmacotherapy Perspectives

24 Nov/Dec 2000 Journal of the Pharmacy Society of Wisconsin

for informational purposes.

Fluoxetine and its s-enantiomer, s-fluoxetine, have been

studied for migraine prophylaxis with mixed results.44-46 A

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 32 patients evaluated

fluoxetine over an 8-week period.44 Headache scores in the

active group decreased significantly beginning in the third and

fourth weeks of treatment; no change was observed in the

placebo group. No changes in depression scores were observed

in either group. A second trial evaluated fluoxetine vs. placebo

in 122 patients with migraine or chronic daily headache.45

Fluoxetine was not significantly effective for migraine in this

study but was moderately effective in reducing chronic daily

headache. S-fluoxetine was evaluated in a placebo-controlled

trial in 53 patients.46 The active treatment resulted in a statis-

tically significant decrease in the number of attacks, although

the decreases in secondary efficacy measures, such as mi-

graine days, attack severity and medication use, did not reach

statistical significance.

Lamotrigine is a newer anticonvulsant that has been ex-

plored for migraine prophylaxis. A study in 15 patients found

that lamotrigine reduced the frequency and duration of aura

symptoms to a statistically significant degree, but this study

did not measure the effect on headaches.47 A second study

evaluated lamotrigine for prevention of migraine with aura in

18 patients.48 Doses of 100 mg/day decreased the number of

attacks per month significantly. This study also treated five

patients who had migraine without aura; they had no reduction

in the number of attacks while on lamotrigine. A third study of

lamotrigine in patients with migraine with and without aura

showed a tendency toward reductions in migraine days and

severity scores for the active treatment group, but no statisti-

cally significant benefits were shown.49

A recent case series on the use of gabapentin in centrally

and peripherally mediated pain, migraine and tremor reported

on 14 patients with migraine and cluster headache who were

treated with gabapentin in doses of 900-2700 mg/day. Ten of

the 14 patients reported moderate to excellent reduction in

headache frequency, duration and severity.50

Other agents currently in use or under investigation for

migraine prevention are riboflavin51, magnesium52,

montelukast53 and sumatriptan (taken intermittently for men-

strual migraine).54 The anticonvulsant topiramate has been

used successfully in refractory patients, although there is very

little published data available. Anecdotal reports have indi-

cated excellent response rates with very little toxicity.

Summary

While there are many apparently effective options avail-

able for the preventive treatment of migraine headache, there

is good supporting data for some and relatively little clinical

data supporting the use of others among these agents. Never-

theless, having a wide variety of drug classes to choose from

affords more opportunities to find a drug that will be effective

and well-tolerated in a given patient. It is unfortunate that so

many migraine sufferers are not receiving adequate medical

management of their condition, because substantial relief is

available with prophylactic treatment. Many of the treatments

are very affordable some costing less per month than a

single dose of the migraine abortive agent sumatriptan. Pa-

tients who are frequent users of abortive medications should be

encouraged to ask their physicians about prophylactic treat-

ment, and if they are not seeing a physician with expertise in

this area, they should be encouraged to seek a referral to one.

The potential gains for patients in reduction of migraine

frequency, pain severity and disability are tremendous.

References available on request. n

Costs: Estimated Average Wholesale Prices

for a One-Month Supply

DRUG

DOSE RANGE

AWP/MONTH

Amitriptyline

10-150 mg/day

$2.72-14.64

Propranolol

40-240 mg/day

$3.90-44.55

Nortriptyline

10-150 mg/day

$10.26-35.55

Metoprolol

100-200 mg/day

$18.63-37.27

Atenolol

50-150 mg/day

$21.60-64.80

Nadolol

20-60 mg/day

$25.64-76.94

Valproic acid

500-1500 mg/day

$49.04-147.15

Diltiazem

90-360 mg/day

$35.27-64.20

Verapamil

240-360 mg/day

$36.30-66.60

Divalproex sodium

500-1500 mg/day

$49.04-147.15

Lamotrigine

100 mg/day

$65.60

Methysergide

2-8 mg/day

$69.59-278.35

Fluoxetine

20-40 mg

$81.30-162.60

Gabapentin

900-2700 mg/day

$104.40-313.20

Topiramate

200 mg/day

$177.19

Nimodipine

120-360 mg/day

$803.00-2411.00

www.your.ehealthcenter.com

independent pharmanex medical rep

Nathalie Knowles-Beck

414-961-9162

male, female, family preventative health care

You might also like

- Anti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIIFrom EverandAnti-Aging Therapeutics Volume XIIINo ratings yet

- Migraine Prophylaxis: Principles, Goals and Drug TherapyDocument5 pagesMigraine Prophylaxis: Principles, Goals and Drug TherapyAndrew MaragosNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Antipsychotic Pharmacotherapy, Other PharmacotherapyDocument13 pagesSchizophrenia Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Antipsychotic Pharmacotherapy, Other PharmacotherapydilaNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Discussion NUR520Document5 pagesModule 3 Discussion NUR52078xh8x8b69No ratings yet

- 2019 Aplicaciones AmericanaDocument18 pages2019 Aplicaciones AmericanaJUAN MANUEL CERON ALVARADONo ratings yet

- The Treatment of Migraine Headaches in Children and AdolescentsDocument11 pagesThe Treatment of Migraine Headaches in Children and Adolescentsdo leeNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDocument16 pagesSchizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDimas Januar100% (2)

- Kung Doris Chronic MigraineDocument19 pagesKung Doris Chronic MigraineAnonymous tG35SYROzENo ratings yet

- New Topics in phaRMcology (97-2003)Document18 pagesNew Topics in phaRMcology (97-2003)api-3761895No ratings yet

- Adult Migraine - Choosing Between TherapiesDocument40 pagesAdult Migraine - Choosing Between TherapiesMohan PrasadNo ratings yet

- Medication Overuse Headache - Treatment and Prognosis - UpToDateDocument16 pagesMedication Overuse Headache - Treatment and Prognosis - UpToDateMarcela Garzon O VelezNo ratings yet

- Anti Psychotic MedicationsDocument6 pagesAnti Psychotic MedicationsCandace AngelNo ratings yet

- BPJ64 PolypharmacyDocument11 pagesBPJ64 PolypharmacyLimYouhokNo ratings yet

- Trend Watch: Treatment of Migraine and The Role of Psychiatric MedicationsDocument3 pagesTrend Watch: Treatment of Migraine and The Role of Psychiatric MedicationsCharbel Rodrigo Gonzalez SosaNo ratings yet

- Preventive Treatment of Migraine in AdultsDocument16 pagesPreventive Treatment of Migraine in AdultsRenato Vilas Boas FilhoNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To PrescribingDocument12 pagesAn Introduction To PrescribingNelly AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- AFP MigrañaDocument9 pagesAFP MigrañaJuaan AvilaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On PolypharmacyDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Polypharmacyefj02jba100% (1)

- Treatment of Mood DisordersDocument27 pagesTreatment of Mood DisordersCamelutza IsaiNo ratings yet

- gl0087 PDFDocument58 pagesgl0087 PDFNurul HikmahNo ratings yet

- Practice GuidelineDocument3 pagesPractice Guidelineclarajimena25No ratings yet

- NICE Guidelines For The Management of DepressionDocument2 pagesNICE Guidelines For The Management of DepressionstefenandreanNo ratings yet

- Maintenan Bipolar With FarmakoEvid Based Mental Health-2014-Malhi-eb-2014-101948Document7 pagesMaintenan Bipolar With FarmakoEvid Based Mental Health-2014-Malhi-eb-2014-101948amro7190No ratings yet

- Migraine PreventionDocument31 pagesMigraine PreventionMohan PrasadNo ratings yet

- Hospital NursingDocument3 pagesHospital NursingrandolphmanalaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy Considerations in Palliative Care: Learning ObjectivesDocument19 pagesPharmacotherapy Considerations in Palliative Care: Learning ObjectivesMajed Mubarak Shannan AlzahraniNo ratings yet

- Depresion en GeriatricosDocument6 pagesDepresion en GeriatricosmmsNo ratings yet

- 10 TH Conf Poly PharmacyDocument5 pages10 TH Conf Poly Pharmacytr14niNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0025712514000893Document32 pagesPi Is 0025712514000893Christoph HockNo ratings yet

- Are There Guidelines For The Responsible Prescription of Benzodiazepines?Document7 pagesAre There Guidelines For The Responsible Prescription of Benzodiazepines?Rian YupitaNo ratings yet

- PN0612 SF MigraineGuidelinesDocument3 pagesPN0612 SF MigraineGuidelinesAlejandra CastilloNo ratings yet

- Group F (Pabellon-Sacramento) - Final ManuscriptDocument35 pagesGroup F (Pabellon-Sacramento) - Final ManuscriptImmah Marie PinedaNo ratings yet

- IkhsanDocument14 pagesIkhsanSilvia Icha RiskiNo ratings yet

- Case Management GuideDocument212 pagesCase Management Guidesheath516100% (2)

- Bpac Polypharmacy Poem 2006 PFDocument20 pagesBpac Polypharmacy Poem 2006 PFJacob Alexander MarpaungNo ratings yet

- Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache: The CaseDocument8 pagesProphylaxis of Migraine Headache: The CaseRo KohnNo ratings yet

- PICOTDocument8 pagesPICOTRaphael Seke OkokoNo ratings yet

- PolypharmacyDocument4 pagesPolypharmacyJeffrey Tan100% (1)

- TP - Tratamiento 2Document17 pagesTP - Tratamiento 2Ilse JuradoNo ratings yet

- Epi Drugs EficaciesDocument18 pagesEpi Drugs EficaciesaandreiiNo ratings yet

- Aripiprazole AugmentationDocument12 pagesAripiprazole AugmentationmissayayayaNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Patient PDFDocument57 pagesGeriatric Patient PDFHasan Al MasudNo ratings yet

- Medication Use in Older Adults by Rose Knapp, MSN, RN, APRN-BC, ANPDocument34 pagesMedication Use in Older Adults by Rose Knapp, MSN, RN, APRN-BC, ANPJose Antonio Tous OlagortaNo ratings yet

- Rational Prescribing & Prescription Writing: IntroductionDocument3 pagesRational Prescribing & Prescription Writing: IntroductionAnmol KudalNo ratings yet

- Practice Parameter: Evidence-Based Guidelines For Migraine Headache (An Evidence-Based Review)Document10 pagesPractice Parameter: Evidence-Based Guidelines For Migraine Headache (An Evidence-Based Review)Arifya Anggoro KasihNo ratings yet

- ManiaDocument2 pagesManiajopet8180No ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacology (Clark's Clinical Medicine 9th Ed (2017) - 2)Document38 pagesClinical Pharmacology (Clark's Clinical Medicine 9th Ed (2017) - 2)Rosulescu IonNo ratings yet

- Guideline Summary NGC-6824: FDA Warning/Regulatory AlertDocument8 pagesGuideline Summary NGC-6824: FDA Warning/Regulatory AlertÜnal ZağliNo ratings yet

- Discontinuing Antidepressant Medications in AdultsDocument16 pagesDiscontinuing Antidepressant Medications in AdultsOm AracoNo ratings yet

- Artikel 1Document6 pagesArtikel 1dyah novitaningrumNo ratings yet

- T H e C U R B S I D e C o N S U L TDocument7 pagesT H e C U R B S I D e C o N S U L TwaftmoversNo ratings yet

- Non-Pharmacological Treatments For Depression in Primary Care - An OverviewDocument8 pagesNon-Pharmacological Treatments For Depression in Primary Care - An OverviewknowlardNo ratings yet

- The STAR D Study: Treating Depression in The Real World: Interpreting Key TrialsDocument10 pagesThe STAR D Study: Treating Depression in The Real World: Interpreting Key Trials★彡ᏦᏖ彡★No ratings yet

- Anesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-2001-3000Document1,000 pagesAnesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-2001-3000rosangelaNo ratings yet

- Best Practice Stopping AntibioticsDocument4 pagesBest Practice Stopping AntibioticsJanine ClaudeNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-2001-3000Document845 pagesAnesthesia Books 2019 Bonica's-2001-3000rosangelaNo ratings yet

- Nejme 2301045Document2 pagesNejme 2301045Billy LamNo ratings yet

- Depresion en El Anciano en APS NejmDocument3 pagesDepresion en El Anciano en APS NejmOscar Alejandro Cardenas QuinteroNo ratings yet

- Clinic 6Document16 pagesClinic 6Renju KuriakoseNo ratings yet

- Wjem 13 01 26 PDFDocument9 pagesWjem 13 01 26 PDFMoises Vega RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Tigecycline - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument8 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Tigecycline - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Donor DarahDocument1 pageDonor Darahjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Dystocia SOGCDocument16 pagesDystocia SOGCAdhitia NugrahantoNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Pulmonary Sequestration: A Case Report and Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesCase Report: Pulmonary Sequestration: A Case Report and Literature Reviewjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Donordarah PDFDocument1 pageDonordarah PDFjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- 111992518Document6 pages111992518jo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Canadian Contraception ConsensusDocument14 pagesCanadian Contraception Consensusjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- AnyelirDocument2 pagesAnyelirjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Chlamydial Infection Can Cause Disease in Many Organ SystemsDocument22 pagesChlamydial Infection Can Cause Disease in Many Organ Systemsjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies Module 1 - A Case of PcosDocument9 pagesCase Studies Module 1 - A Case of PcosBobNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 37.ASPaaaaaDocument6 pagesContentServer 37.ASPaaaaaAchmad Deza FaristaNo ratings yet

- HiResOligonucleoutide ACGH Analysis Under24Hrs AppNote5991-0643ENDocument8 pagesHiResOligonucleoutide ACGH Analysis Under24Hrs AppNote5991-0643ENjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Bioethic MetaphysicDocument6 pagesBioethic Metaphysicjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Induction of Labour Versus Expectant Monitoring ForDocument11 pagesInduction of Labour Versus Expectant Monitoring Forjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Cancer RiskDocument1 pageCancer Riskjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- IBT Q4 03 ReadingonlyDocument1 pageIBT Q4 03 Readingonlyjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Speaking - Question 1&2 TopicsDocument8 pagesTOEFL Speaking - Question 1&2 TopicsSiddharthaSidNo ratings yet

- Yg Belum Masuk IpadDocument1 pageYg Belum Masuk Ipadjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

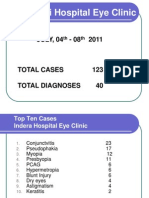

- NEW Weekly Indra 04-08 July 2011Document13 pagesNEW Weekly Indra 04-08 July 2011jo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Structure Content: 1. EXERCISE 1 (Skill 1-2) 2. Toefl Review Exercise (Skill 1-2) 3. Answer KeysDocument3 pagesStructure Content: 1. EXERCISE 1 (Skill 1-2) 2. Toefl Review Exercise (Skill 1-2) 3. Answer Keysjo_jo_mania0% (1)

- BARUPoliklinik Wangaya 4-8 Juli 2011Document14 pagesBARUPoliklinik Wangaya 4-8 Juli 2011jo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Sunday, 26/09 /2010 PT/LN/MG:: Consultant DR Mas Putra SPMDocument6 pagesSunday, 26/09 /2010 PT/LN/MG:: Consultant DR Mas Putra SPMjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Prediction Reccurence Prostat CADocument9 pagesPrediction Reccurence Prostat CAjo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- International Centre For Eye Health Teaching Set 2 The Eye in Primary Health CareDocument25 pagesInternational Centre For Eye Health Teaching Set 2 The Eye in Primary Health Carejo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- OrtoDocument61 pagesOrtojo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Laser Iridotomy and GlaucomaDocument2 pagesLaser Iridotomy and Glaucomajo_jo_maniaNo ratings yet

- Arterial Blood Gas: DR - Made Widia, Sp.A (K)Document19 pagesArterial Blood Gas: DR - Made Widia, Sp.A (K)jo_jo_mania100% (1)

- Beyond Wedge: Clinical Physiology and The Swan-Ganz CatheterDocument12 pagesBeyond Wedge: Clinical Physiology and The Swan-Ganz Catheterkromatin9462No ratings yet

- Cataract Case PresentationDocument7 pagesCataract Case PresentationShahbaz AAnsariNo ratings yet

- Best Milking Practices Checklis PDFDocument3 pagesBest Milking Practices Checklis PDFcan_orduNo ratings yet

- Egurukul OrbitDocument8 pagesEgurukul OrbitbetsyNo ratings yet

- Ptisis BulbiDocument6 pagesPtisis Bulbiruditacitrahaha100% (1)

- Main Conference ProgrammeDocument7 pagesMain Conference ProgrammeFaadhilah HussainNo ratings yet

- KN 4@enzl 8 Ha 4 B 6 CC 9 eDocument26 pagesKN 4@enzl 8 Ha 4 B 6 CC 9 eRamzen Raphael DomingoNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Handout 2Document12 pagesBipolar Handout 2hugoi_7No ratings yet

- Congenital Ichthyosis - Collodion Baby Case Report: KeywordsDocument2 pagesCongenital Ichthyosis - Collodion Baby Case Report: KeywordsLidia MdNo ratings yet

- Elite Package Marketing PlanDocument30 pagesElite Package Marketing PlanNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- Safety Seal Certification ChecklistDocument2 pagesSafety Seal Certification ChecklistKathlynn Joy de GuiaNo ratings yet

- Scenar Testimonials (Updated)Document10 pagesScenar Testimonials (Updated)Tom Askew100% (1)

- Screenshot 2022-10-21 at 19.56.24Document3 pagesScreenshot 2022-10-21 at 19.56.24Zafira AkramNo ratings yet

- 2015catalog PDFDocument52 pages2015catalog PDFNegoi Mihai0% (1)

- Cerebral Palsy Brain Paralysis: Complications of Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocument11 pagesCerebral Palsy Brain Paralysis: Complications of Neurodevelopmental DisordersmikayNo ratings yet

- TetanusDocument7 pagesTetanusallah akbarNo ratings yet

- The Well-Being of The EMT: Emergency Medical Technician - BasicDocument30 pagesThe Well-Being of The EMT: Emergency Medical Technician - Basicalsyahrin putraNo ratings yet

- Tugas B.inggrisDocument7 pagesTugas B.inggrisIis setianiNo ratings yet

- Dialog Percakapan Bidan Tugas Bahs Inggris DedeDocument5 pagesDialog Percakapan Bidan Tugas Bahs Inggris DedeSardianto TurnipNo ratings yet

- Spinal InjuryDocument24 pagesSpinal InjuryFuad Ahmad ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Experiment #15: Screening Test For Low Titer Group "O" BloodDocument5 pagesExperiment #15: Screening Test For Low Titer Group "O" BloodKriziaNo ratings yet

- Mean Alt Üst SD Range Mean Alt Üst SD Range Mean Alt Üst SD Mean Alt Üst SD FaktörDocument5 pagesMean Alt Üst SD Range Mean Alt Üst SD Range Mean Alt Üst SD Mean Alt Üst SD FaktörZeynep DenizNo ratings yet

- TCM Protocol For ClassicalDocument26 pagesTCM Protocol For ClassicalDrnarendra KumarNo ratings yet

- HTP Visual1Document3 pagesHTP Visual1Queeniecel AlarconNo ratings yet

- Tipos de SuturasDocument5 pagesTipos de SuturasLeandro PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Phase II CurriculumDocument136 pagesPhase II CurriculumNil NilNo ratings yet

- Asbestos Awareness Quiz #1: AnswersDocument2 pagesAsbestos Awareness Quiz #1: AnswersMichael NcubeNo ratings yet

- Prumychild EngDocument12 pagesPrumychild EngAmirol Ariff NazarudinNo ratings yet

- Cyclamen: Chilly PulsatillaDocument10 pagesCyclamen: Chilly Pulsatillaअनुरूपम स्वामीNo ratings yet

- Pe Lesson 1 LifestyleDocument17 pagesPe Lesson 1 LifestyleKeil San PedroNo ratings yet