Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lessons From A Hanging

Uploaded by

RajatBhatiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lessons From A Hanging

Uploaded by

RajatBhatiaCopyright:

Available Formats

june 21, 2014

Economic & Political Weekly EPW june 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25

7

Lessons from a Hanging

The Budaun rape and murder exposes the everyday reality of sexual violence.

I

n the iconography of rape and sexual violence, the image of two

teenage g irls hanging from a mango tree in Katra Sadatganj

village, Budaun district, Uttar Pradesh (UP), will be long remem-

bered. The image, including the depiction of mute onlookers, tells

us more than what happened on the night of 27 May 2014. The two

cousins went out under cover of darkness to the elds, their only

toilet, as they would have done everyday. Yet this day was not like

every other day as they were dragged away by a group of men, gang-

raped and their ravaged bodies strung up and hung from a tree.

The fact that the two girls belonged to a lower caste, while

their alleged rapists and murderers are of the caste that now

rules UP, reects the dismal reality that caste-based violence is

nowhere near ending in 21st century India. The fact that even as

these men raped and killed the two girls they also chose to hang

their dead and assaulted bodies from a tree tells us how men

from politically powerful castes seek to send out a message to

those they oppress. It also exposes their sense of impunity

because they know their kin hold the reins of political power.

The incident also shows us the complete helplessness of the lower

castes in such situations. When the father of one of the girls

went to the police to report her missing, he was slapped around

and sent back. That the families have demanded, and got, the

government to agree to a Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI)

inquiry under these circumstances is hardly surprising.

The Budaun horror is neither the rst nor the last. It is a part

of the story of everyday violence that marks the lives of women,

particularly lower caste women, living in villages and small towns.

These daily episodes of violence escape the scrutiny of the media.

Yet, if one of them does get highlighted, there is a spurt of report-

ing on other such crimes. Thus, within days of the Budaun rape

and murder, many more rapes and assaults were reported: a

19-year-old girl in Gurgaon, an IT professional in Bangalore, a

woman bus conductor in Maharashtra, women in Jharkhand,

Rajasthan, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, and West Bengal. Another

woman raped and hung in UP. A woman shot by suspected mili-

tants in Meghalaya for resisting rape. Meanwhile, 80 families

from Bhagana village in Haryana, where four young women

were allegedly raped and then left at a railway station away

from their homes, continue to sit in the scorching heat in Delhi

demanding justice. So Budaun is exceptional and yet it is part of

the depressing and wretched reality of womens lives all over

this country.

Nor is UP the only state with insensitive politicians belonging to

the ruling Samajwadi Party who have no compunction in making

politically inappropriate statements to explain away or justify

rape. They have company, representing men of all political hues

ranging from Madhya Pradesh Home Minister Babulal Gaur of

the Bharatiya Janata Party who says rape is sometimes its right,

sometimes its wrong, to another member of his party, Ramsevak

Paikra, Home Minister of Chhattisgarh who suggests that rape

happens by mistake and that nobody commits rape on pur-

pose, to Maharashtra Home Minister R R Patil of the Nationalist

Congress Party who thinks that it is impossible to prevent rape

because the majority of rapes occur within homes where police-

men cannot be posted. Furthermore, for Prime Minister Narendra

Modi not to make a statement for days after the Budaun incident

nor reprimand members of his own party for their insensitivity,

also underlines the lack of seriousness in the political class as a

whole towards the escalation of violence against women in India.

Yet, what these politicians are saying, or not saying, reects

the dominant culture of rape and its acceptance in the country.

When a sensational rape is reported, such as the 16 December

2012 Delhi gang rape, or this latest horror from Budaun, inquir-

ies are held, committees are set up, scapegoats are found. Yet

rarely do we see a realistic discussion on the factors contribut-

ing to the culture of rape as is evident from the steady increase

in the number of crimes against women being reported.

What are the factors fuelling the growth and spread of this cul-

ture? Why has so-called modernity not even touched the patriarchal

and misogynist attitudes that encourage successive generations of

Indian men to believe that they are entitled to do as they wish with

women, including those who belong to them? And why, despite

the focus on violence against women in recent years and stronger

laws, are the criminals who commit these crimes not deterred?

The answers to these questions are not simple. They require

serious engagement from policymakers, educationists, media

practitioners and activists. A culture that is so entrenched can-

not be changed overnight. But a dent can be made if we rst ac-

knowledge the nature and the extent of the rape culture and

then identify the small steps that can be taken more effective

policing and implementation of laws, a higher conviction rate,

improved sanitation for women, etc. All this will help but the far

bigger challenge of altering the landscape of mens minds is a

longer journey, one that is difcult yet unavoidable.

You might also like

- THE GODFATHER ScriptDocument179 pagesTHE GODFATHER ScriptCrisshna Calyan67% (3)

- Jack Ruby - The Zionist Puppet - SpanishhalyonDocument18 pagesJack Ruby - The Zionist Puppet - SpanishhalyonHansley Templeton Cook100% (1)

- Aberrant UnderworldDocument97 pagesAberrant UnderworldReaver4675% (4)

- White Dragon Society $25 TrillionDocument2 pagesWhite Dragon Society $25 TrillionHenry John0% (1)

- Handrahan Motion Modify Child Support and VisitationDocument6 pagesHandrahan Motion Modify Child Support and VisitationLori HandrahanNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Fulford 8-24-15 - A Review of The Current Alliances of Secret Societies and Visible Power CentersDocument3 pagesBenjamin Fulford 8-24-15 - A Review of The Current Alliances of Secret Societies and Visible Power CentersFreeman LawyerNo ratings yet

- Icons of Hip Hop (Two Volumes) An Encyclopedia of The Movement, Music, and CultureDocument683 pagesIcons of Hip Hop (Two Volumes) An Encyclopedia of The Movement, Music, and CultureAlejandro FloresNo ratings yet

- Drive Script Analysis PDFDocument13 pagesDrive Script Analysis PDFresevoirdNo ratings yet

- Easy Meat: Multiculturalism, Islam and Child Sex SlaveryDocument333 pagesEasy Meat: Multiculturalism, Islam and Child Sex SlaveryTarek Fatah100% (2)

- Terrorism: Gender and IdentityDocument7 pagesTerrorism: Gender and IdentityIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Blood and RosesDocument167 pagesBlood and RosesBemnet TayeNo ratings yet

- Chin, Ko-Lin and Roy Godson (2006) - Organized Crime and The Political-Criminal Nexus inDocument40 pagesChin, Ko-Lin and Roy Godson (2006) - Organized Crime and The Political-Criminal Nexus inMarch FalentinoNo ratings yet

- CoteriesDocument12 pagesCoteriesLokiMaleficentNo ratings yet

- Necromunda Ogryn Gang RulesDocument3 pagesNecromunda Ogryn Gang RulesmrplttNo ratings yet

- Bratva Bride - T J MaguireDocument349 pagesBratva Bride - T J Maguireacevedorivera03No ratings yet

- Bungo Stray Dogs, Vol. 7 - Dazai, Chuuya, Age FifteenDocument127 pagesBungo Stray Dogs, Vol. 7 - Dazai, Chuuya, Age Fifteenalkalw342100% (3)

- Causes and Prevention of Crimes Against WomenDocument8 pagesCauses and Prevention of Crimes Against Womenpaw27No ratings yet

- The Delhi Rape and The Social ChallengeDocument2 pagesThe Delhi Rape and The Social ChallengeRakesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Violence Against Women in Politics Rising in Pakistan, India: StudyDocument5 pagesViolence Against Women in Politics Rising in Pakistan, India: StudyAbdul HaseebNo ratings yet

- Business Satistics: Rape (ST/SC)Document10 pagesBusiness Satistics: Rape (ST/SC)Saloni KumarNo ratings yet

- Hathras Gang Rape - Women Safety & Caste PoliticsDocument20 pagesHathras Gang Rape - Women Safety & Caste PoliticsSaksham SainiNo ratings yet

- Rights Expansion and Societal Pushback in IndiaDocument3 pagesRights Expansion and Societal Pushback in IndiaMehar ChandNo ratings yet

- Selling The Dream For A Song: Playing With FireDocument1 pageSelling The Dream For A Song: Playing With FireNiteshkr20No ratings yet

- A Dangerous New Low in State-Sponsored Hate - The HinduDocument4 pagesA Dangerous New Low in State-Sponsored Hate - The HindushamshadkneNo ratings yet

- India: On The Edge of DeclineDocument27 pagesIndia: On The Edge of DeclineAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- The Trophies of Operation Green Hunt: National OpinionDocument3 pagesThe Trophies of Operation Green Hunt: National OpinionSiddharth JoshiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of RapeDocument2 pagesAnatomy of RapevirensanNo ratings yet

- Socio-Legal Exposition of Crime Against WomenDocument200 pagesSocio-Legal Exposition of Crime Against WomenMridul SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Artikel Mid-Semester Test 2023Document5 pagesArtikel Mid-Semester Test 2023yunilarasati111No ratings yet

- Avalon Heights International School: India's Growing Acceptance of ViolenceDocument3 pagesAvalon Heights International School: India's Growing Acceptance of ViolenceJesal PorechaNo ratings yet

- Honour Killing - Crime Against Mankind: DR - Saraswati Raju IyerDocument4 pagesHonour Killing - Crime Against Mankind: DR - Saraswati Raju IyerInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Proletarian EraDocument26 pagesProletarian EraSibanisankar MishraNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 3 Ipc ProjectDocument85 pages10 - Chapter 3 Ipc ProjectSushmita GuptaNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3 Crime Against Women: Types and Causes: 3.1 IntroductoryDocument85 pagesChapter - 3 Crime Against Women: Types and Causes: 3.1 IntroductorySairaj ToraskarNo ratings yet

- Final FileDocument81 pagesFinal FileGreen City SoftwaresNo ratings yet

- Violence Against Women in Pakistan........Document6 pagesViolence Against Women in Pakistan........Nashrah ShakeelNo ratings yet

- Crime Against Women by KIMDocument12 pagesCrime Against Women by KIMsubhamaybiswasNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 5 Legislative and Judicial Approch Before and After Criminal Amendment Act-2013Document94 pagesChapter - 5 Legislative and Judicial Approch Before and After Criminal Amendment Act-2013Jayaraman AdvocateNo ratings yet

- Collection of Annotations Case of An Innocent Girl in Unvirtuous SystemDocument3 pagesCollection of Annotations Case of An Innocent Girl in Unvirtuous Systemहुमागाँई शिशिरNo ratings yet

- Preventing Violence Against Women Through Education and AdvocacyDocument6 pagesPreventing Violence Against Women Through Education and AdvocacyKM VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Honour KillingsDocument3 pagesHonour KillingsRitika ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Prevalance of Marital RapeDocument4 pagesPrevalance of Marital RapePrithviraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Not Just A Joke The Social Cost of Duterte's Rape RemarksDocument5 pagesNot Just A Joke The Social Cost of Duterte's Rape RemarksSheenlou Eian BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Is India Safe For WomenDocument10 pagesIs India Safe For WomensumanNo ratings yet

- Not All Wounds Are VisibleDocument3 pagesNot All Wounds Are Visiblemuskan taliwalNo ratings yet

- Violence Against Dalit Woment PDFDocument23 pagesViolence Against Dalit Woment PDFFiraqi GkpNo ratings yet

- Social Research Methods ProposalDocument10 pagesSocial Research Methods ProposalAnnet MutabarukaNo ratings yet

- 10 - Breeders of Machismo CultureDocument2 pages10 - Breeders of Machismo CultureRahul ShahNo ratings yet

- 10 - Breeders of Machismo CultureDocument2 pages10 - Breeders of Machismo CultureRahul ShahNo ratings yet

- Indian Down Under - February 2013Document60 pagesIndian Down Under - February 2013indiandownunderNo ratings yet

- PA-312 by Osman Goni 18 PAD 004Document4 pagesPA-312 by Osman Goni 18 PAD 004ওসমান গণি রেসানীNo ratings yet

- Payam Essay Atrocities On WomenDocument4 pagesPayam Essay Atrocities On WomenTejas Pandey100% (1)

- Women Safety in DelhiDocument60 pagesWomen Safety in DelhiRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamNo ratings yet

- Caste DiscriminationDocument2 pagesCaste DiscriminationAnaya PillaiNo ratings yet

- RANCHI GBV WORKSHOP - "WOMEN: Understanding My Responsibility in Addressing Gender-Based Violence and Inequality"Document49 pagesRANCHI GBV WORKSHOP - "WOMEN: Understanding My Responsibility in Addressing Gender-Based Violence and Inequality"ravikantsvNo ratings yet

- What Is Violence Against WomenDocument23 pagesWhat Is Violence Against WomenaakashagarwalNo ratings yet

- War On Women PDFDocument3 pagesWar On Women PDFHaider razaNo ratings yet

- Honor Killing (Emphasis On India)Document24 pagesHonor Killing (Emphasis On India)Hansel V MendoncaNo ratings yet

- Civil Services Mentor February 2013Document131 pagesCivil Services Mentor February 2013mkrao_kiranNo ratings yet

- Domestic Violence in IndiaDocument14 pagesDomestic Violence in IndiaRishi SehgalNo ratings yet

- PPT CJFRDocument8 pagesPPT CJFRmanpreet kaurNo ratings yet

- Mukhtar MaiDocument36 pagesMukhtar MaimahNo ratings yet

- Crimes Against Women: Three Tragedies and the Call for Reform in IndiaFrom EverandCrimes Against Women: Three Tragedies and the Call for Reform in IndiaNo ratings yet

- Go-Gi-Sgk Dimalanta - 4Document7 pagesGo-Gi-Sgk Dimalanta - 4api-512999212No ratings yet

- Book Review - The Persistence of CasteDocument4 pagesBook Review - The Persistence of CasteSheenam KohliNo ratings yet

- North South University: AssignmentDocument6 pagesNorth South University: AssignmentFardin MahamudNo ratings yet

- Violence Against WomenDocument5 pagesViolence Against WomenAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Social Dominance Orientation and Sexual Violence Against Dalit Women in IndiaDocument9 pagesSocial Dominance Orientation and Sexual Violence Against Dalit Women in Indiadr.amol.psyNo ratings yet

- DR Pandey SushmaDocument8 pagesDR Pandey SushmaSyed Danish FayazNo ratings yet

- Data Journalism: 1st Place - Esther Namugoji, Mary Karugaba, Moses Walubiri, John Masaba, John Semakula, New VisionDocument3 pagesData Journalism: 1st Place - Esther Namugoji, Mary Karugaba, Moses Walubiri, John Masaba, John Semakula, New VisionAfrican Centre for Media ExcellenceNo ratings yet

- Honorkillingin IndiaDocument18 pagesHonorkillingin IndiashreyaNo ratings yet

- LibroDocument23 pagesLibroLissette MoralesNo ratings yet

- Unpacking Participation in Kathputli ColonyDocument9 pagesUnpacking Participation in Kathputli ColonydervishdancingNo ratings yet

- What Future For The Media in IndiaDocument5 pagesWhat Future For The Media in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

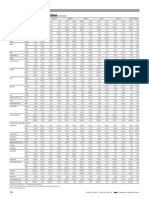

- Trends in Agricultural ProductionDocument1 pageTrends in Agricultural ProductionRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Wither On The VineDocument3 pagesWither On The VineRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- The Ehsan Jafri CaseDocument3 pagesThe Ehsan Jafri CaseRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Some Notes On The Indian Economy in CrisisDocument10 pagesSome Notes On The Indian Economy in CrisisAbhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Discreet Charm of The BJPDocument4 pagesThe Discreet Charm of The BJPRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shandana MinhasDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shandana MinhasRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- The History of CasteDocument3 pagesThe History of CasteRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Safe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityDocument6 pagesSafe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Sealing The Victory of The Corporate Sector 2Document3 pagesSealing The Victory of The Corporate Sector 2Kannan P NairNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Nada FarisDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Nada FarisRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- No Freedom To DespiseDocument2 pagesNo Freedom To DespiseRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Northeast Indians and OthersDocument3 pagesNortheast Indians and OthersRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceDocument3 pagesMaking Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaDocument5 pagesRevisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- ED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleDocument1 pageED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Known Unknowns of RTIDocument7 pagesKnown Unknowns of RTIRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Latin American Marxist PerspectivesDocument4 pagesLatin American Marxist PerspectivesRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Sons of The GangaDocument4 pagesSons of The GangaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Political Power and Democratic EnablementDocument9 pagesPolitical Power and Democratic EnablementRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- From 50 Years AgoDocument1 pageFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- After Apartheid and MandelaDocument5 pagesAfter Apartheid and MandelaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- What Future For The Media in IndiaDocument3 pagesWhat Future For The Media in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- AAP at The CrossroadsDocument1 pageAAP at The CrossroadsKrishna VrNo ratings yet

- Murder Most FoulDocument1 pageMurder Most FoulRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Legislation For The Real Estate SectorDocument8 pagesLegislation For The Real Estate SectorRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Multi-Agency Gang Investigations Briefing: These Minutes Are Not For Public DisseminationDocument5 pagesMulti-Agency Gang Investigations Briefing: These Minutes Are Not For Public DisseminationArizonaMilitiaNo ratings yet

- Chrollo Lucilfer - Hunterpedia - FandomDocument18 pagesChrollo Lucilfer - Hunterpedia - FandomRolando Segundo Cortez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Yakuza RitualsDocument2 pagesOverview of Yakuza RitualsAlex TiglaoNo ratings yet

- Mafia Film Journal - Donnie BrascoDocument3 pagesMafia Film Journal - Donnie BrascoCRAIG_FREESENo ratings yet

- Jason Treas Testimony Nov 4, 2010 USA Eastern DistrictDocument80 pagesJason Treas Testimony Nov 4, 2010 USA Eastern Districtali_winston100% (1)

- Types of Organized CrimesDocument4 pagesTypes of Organized CrimesIshita GosaliaNo ratings yet

- Cmy3706 Exam PrepDocument14 pagesCmy3706 Exam Prepry9w4mqjs6No ratings yet

- Organized CrimeDocument10 pagesOrganized CrimeMaryam AhmadiNo ratings yet

- Honduras Reflective EssayDocument5 pagesHonduras Reflective Essayapi-341639901No ratings yet

- All Eyez On MeDocument4 pagesAll Eyez On MeDragana TabakovicNo ratings yet

- English Test NounsDocument3 pagesEnglish Test NounsMadalina ArdeleanNo ratings yet

- Frank Cullotta, Late Chicago and Vegas Mobster, Publishes Posthumous Gangster's CookbookDocument3 pagesFrank Cullotta, Late Chicago and Vegas Mobster, Publishes Posthumous Gangster's CookbookPR.comNo ratings yet

- Topic Read and Write Feb 14Document1 pageTopic Read and Write Feb 14Jomar SolivaNo ratings yet

- 40 Guide Odessa GRDocument192 pages40 Guide Odessa GRO TΣΑΡΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΤΙΒΑΡΥΤΗΤΑΣ ΛΙΑΠΗΣ ΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣNo ratings yet