Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pakistan's Economic Performance and Prospects in FY2014

Uploaded by

Abdul Ghaffar BhattiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakistan's Economic Performance and Prospects in FY2014

Uploaded by

Abdul Ghaffar BhattiCopyright:

Available Formats

This chapter was written by Sharad Bhandari and Farzana Noshab of the Pakistan

Resident Mission, ADB, Islamabad.

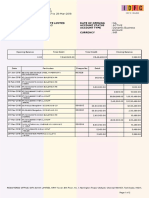

3.20.1Supply-side contributions to growth

Agriculture

Industry

Services

Gross domestic product

Percentage points

.

.

.

.

.

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: Ministry of Finance. Pakistan Economic Survey

201213. http://www.nance.gov.pk

Click here for gure data

Pakistan

Macroeconomic and security challenges continue to weigh on the economy. Growth is expected

to remain modest in FY2014, largely reflecting fiscal consolidation to deal with high deficits

that have caused macroeconomic imbalances. The government has embarked upon a program

of fiscal and structural reform, supported by an Extended Fund Facility Arrangement with the

International Monetary Fund, to restore macroeconomic balance, relieve energy shortages, and

guide the economy toward faster and more sustainable growth.

Economic performance

Moderate GDP growth in FY2013 reected weak macroeconomic

fundamentals in recent years. Investment remained low as energy

shortages and security concerns continued to undermine investor

condence. Fiscal pressures kept the budget decit very high for the

second consecutive year. At the same time, however, ination fell into

single digits. Stable global commodity prices, Coalition Support Fund

(CSF) inows, and continued growth in worker remittances reined in

the current account decit.

GDP growth slowed to 3.6% in FY2013 (ended 30 June 2013) as weak

expansion in the large service sector more than ofset improved growth

in manufacturing (Figure 3.20.1). Growth in agricultural production

slowed slightly on weaker output of major crops, especially cotton

and rice. Manufacturing expanded by 3.5%, reecting a 4.4% pickup

in large-scale manufacturing, though the sector remained hobbled by

a continued power crisis and weak internal security. Textiles, food

processing, and construction materials showed faster growth. Improved

performance in construction was supported by ood rehabilitation,

other public sector development projects, and their positive spillover

efects to rest of the economy. Low growth in services was caused

mainly by a slowdown in telecommunications. This countered

improvement in nance and insurance that, however, reected little

more than commercial banks prots from their high investment in

government securities.

Investment continued its downward trend, with xed investment

falling from 13.3% of GDP in FY2012 to 12.6%. Private investment fell

to 8.7% of GDP in large part because investment in manufacturing

weakened, likely reecting power shortages and low condence

in the countrys economic prospects, while investment in services

also slipped (Figure 3.20.2). Consumption growth slowed to 4.6% in

FY2013 from 6.0% in the previous year but still outpaced GDP growth.

Private consumption eased as growth in remittance inows slowed.

3.20.2Gross fixed capital formation

7 of GDP

0

4

8

J2

J6

20J3 20J2 20JJ 20J0 2009

Manufacturing

Transport & communication

Services

Others

Agriculture

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: Ministry of Finance. Pakistan Economic Survey

201213. http://www.nance.gov.pk

Click here for gure data

Asian Development Bank

Asian Development Outlook 2014

Fiscal Policy for Inclusive Growth

To access the complete publication

click here

182Asian Development Outlook 2014

Government spending, on the other hand, continued to exhibit strong

growth. Positive net exports reected improved export volume and a

decline in imports as investment fell.

Headline ination slowed from 11.0% in FY2012 to average 7.4%

in FY2013, as food shortages eased (Figure 3.20.3). Gas tarif cuts and

easing global commodity prices during the year moderated the rise of

food and other prices. Greater exchange rate stability in FY2013as

compared with signicant depreciation against the US dollar in the year

beforealso helped contain inationary expectations. Ination averaged

7.1% for food and 7.5% for non-food items.

The scal decit stood at 8.0% of GDP in FY2013, lower than the

8.8% recorded in FY2012. It reected low tax revenues and higher

current expenditures on power subsidies, pensions, and interest on

short-term domestic borrowing. The unbudgeted clearance of power

sector debt amounted to 1.4% of GDP. Consolidated development

expenditures in FY2013 were 6.3% lower than the target, on account of

smaller provincial development outlays.

Federal tax revenues grew by a meager 3.2%, undermined by lower

income tax and general sales tax collection and falling short of the

FY2013 annual target. Federal Board of Revenue tax revenues grew

by only 2.9% and, at PRs1.94 trillion, were below the revised target

of PRs2.01 trillion. As such, they cover only about half of current

consolidated budget expenditure, which is a pattern that has prevailed

over the past 5 years (Figure 3.20.4). The shortfall in tax collection in

FY2013 was partly compensated by higher nontax revenues, including

the receipt of $1.8 billion under the CSF.

Monetary policy was accommodating. As ination began to

decelerate, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the central bank, began in

August 2012 to cut its policy rate gradually by a cumulative 300 basis

points to 9.0% at the end of June 2013 (Figure 3.20.5). Government

borrowing from the SBP and commercial banks remained high, as

foreign nancing was negligible. Budgetary borrowing from banks

increased by 28%, or PRs1.5 trillion, in FY2013, including net borrowing

of PRs536 billion from the SBP. To maintain market liquidity, the SBP

injected, through open market operations, double the amount of funds

injected in FY2012. However, credit to the private sector showed a slight

net contraction in FY2013, as banks preferred to invest in government

securities and economic activity remained weak. The heavy reliance

on short-term borrowing has increased the governments exposure to

interest rate and rollover risks.

The current account decit narrowed to $2.3 billion, or 1% of

GDP, in FY2013 with improvement in the trade decit, a lower service

account decit following receipts under the CSF, and continued inows

of worker remittances. Imports declined by 0.6% while export growth

remained positive at 0.4%. A fall in external loan and nondebt nancing,

larger external debt repayment, and SBP interventions in the foreign

exchange market to limit local currency depreciation drained foreign

exchange reserves to a critically low $6.0billion, enough to cover only

1.3months of imports of goods and services by the end of June 2013.

ThePakistani rupee depreciated against the dollar to Rs98.5, a decline

of 4.5% over the year.

3.20.3Inflation

7

Food

Nonfood

Overall

0

5

J0

J5

20

20J3 20J2 20JJ 20J0

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: CEIC Data Company (accessed 6 March 2014).

Click here for gure data

3.20.4Current revenue and expenditure

of GDP

Interest payments

Subsidies

Pensions

Others

Federal Board of Revenue tax revenue

Defense

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: Pakistan Economic Survey 201213; Pakistan Fiscal

operations 201112 www.nance.gov.pk

Click here for gure data

3.20.5Banking sector credit

PRs trillion 7

Government sector

Loans to private

sector business Policy rate

0

2

4

6

8

J0

0

3

6

9

J2

J5

1an

20J4

1ul 1an

20J3

1ul 1an

20J2

1ul 1an

20JJ

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data. http://

www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 14 February 2014).

Click here for gure data

Economic trends and prospects in developing Asia: South Asia Pakistan183

Economic prospects

GDP growth is projected at 3.4% for FY2014, marginally slower than in

FY2013. Agriculture is expected to be weaker due to a drop in cotton

output, which will partly ofset improvement in the sugarcane and

ricecrops. Current rains may benet the upcoming wheat crop, despite a

reduction in the area sowed this year.

Weak agriculture will be partly compensated by the pickup in

large-scale manufacturing, which grew by 6.7% during the rst

6months of FY2014, three times the rate during the same period a

year earlier (Figure 3.20.6). Larger and more reliable power supply

partly reecting better controls on unscheduled load shedding, as

well as the increasing use of alternative fuelsis helping to revive

the production of food, fertilizers, chemicals, electronics, and

leather products, while petroleum renery output continued its

robust growth. Textiles are expected to recover from existing weak

growth as they benet from Generalized Scheme of Preferences

Plus status granted by the EuropeanUnion from January 2014.

Improved manufacturing performance will spur retail and trade

activity. Performance in transport and communication will continue

to be afected by nancial losses incurred by Pakistan Railways and

PakistanInternationalAirlines.

On the demand side, private consumption will remain the main

driver of economic growth, supported by the sustained inow of

remittances, low real interest rates, and better credit availability at

banks. Government spending will be contained by scal consolidation

to bring down the budget decit, but accelerated credit ows to the

private sector during the rst 7 months of FY2014 indicate an uptick in

private investment. Net exports are expected to be modestly negative

as import growth quickens to support improved capacity utilization in

manufacturing. GDP growth is expected to be higher in FY2015, at 3.9%,

as the impact of scal consolidation eases somewhat, energy supplies

improve, and the global economy strengthens.

In the rst 8 months of FY2014, ination averaged 8.6%, reecting

the increase in the general sales tax rate by 1 percentage point to 17%,

increases in power tarifs in August and October 2013 for commercial

and bulk residential and industrial users, and signicant Pakistan rupee

depreciation against the major currencies. Reecting short supply of

perishable items and higher wheat prices, food ination rose to 13.0% in

November 2013 before receding to 7.2% in January 2014 for an average

of 9.3% over the 8 months (Figure 3.20.7). Core ination was relatively

stable and averaged 8.4% during the period. Further adjustments to

electric and gas tarifs, as well as a levy to support gas infrastructure

development, are expected to keep ination elevated over the forecast

period. Average consumer price ination is projected at 9.0% in FY2014

and 9.2% in FY2015.

Monetary policy was tightened in response to a depreciating

currency and rising ination during the rst half of the FY2014.

TheSBP raised the policy interest rate by 50basis points in September

2013 and again in November, bringing it up to 10% from 9% in FY2013

(Figure 3.20.8). While ination eased in January 2014, the SBP kept the

policy rate unchanged in its monetary policy meeting that month.

3.20.6Large-scale manufacturing

-8

-4

0

4

8

1ulDec

20J4

1ulDec

20J3

20J3 20J2 20JJ 20J0 2009 2008

7

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan.

Click here for gure data

3.20.7Monthy inflation

0

3

6

9

J2

J5

1an

20J4

Oct 1ul Apr 1an

20J3

Oct 1ul

20J2

Food

Core

Headline

7, year on year

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data.

http://www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 12 March 2014).

Click here for gure data

3.20.1Selected economic indicators (%)

2014 2015

GDP growth 3.4 3.9

Ination 9.0 9.2

Current account balance

(share of GDP)

1.4 1.3

Source: ADB estimates.

184Asian Development Outlook 2014

Monetary management continues to be challenged by high

government borrowing from the banking system in FY2014. As a result,

the end-December International Monetary Fund (IMF) ceiling for

government borrowing from SBP was breached. As foreign inows

remained negligible, and commercial banks lacked interest in government

securities because short-term money market rates had risen more

quickly than the policy rate, the burden of borrowing once again shifted

from commercial banks to the SBP. From 1 July 2013 to 21February

2014, government borrowing from the SBP increased to PRs890 billion,

against net retirement to commercial banks of PRs184billion. Credit to

the private sector picked up to PRs280billion during this period from

PRs107 billion a year earlier, largely reecting credit to private businesses

for xed investment and working capital as business activity in textiles,

power, and trade improved, as well as for consumer credit. Weighted

average bank lending rates have been relatively stable at just over 10%.

Broad money growth slowed to 4.9% during this period from 7.5% in

the previous year, as the marked contraction in the banking systems

netforeign assets reected a deteriorating balance of payments.

The scal framework under the 3-year extended fund facility agreed

in September 2013 with the IMF focuses on strengthening the revenue

base, limiting power subsidies, ending the drain on the budget from

loss-making state-owned enterprises, and compressing non-salary

expenditure. With the framework, the budget decit excluding grants

is expected to be held to 5.8% of GDP in FY2014, which is somewhat

lower than the original budget target of 6.3% (Figure3.20.9). The scal

decit was contained at 2.1% of GDP during the rst half of the FY2014,

mainly by higher sales tax revenues, $322 million in CSFreceipts, and

restrained expenditure. Theincrease in tax revenues partly reects

measures already taken under the federal budget for FY2014, including

raising the general sales tax rate and eliminating some tax exemptions.

Tax collection of PRs1.031 trillion during rst 6months is broadly

consistent with the scal framework target of PRs2.3trillion for FY2014.

Consolidated expenditure for the rst half of FY2014 was contained

partly by reduced interest payments following the earlier clearance of

accumulated power sector arrearsthe circular debt. Interest payments

are likely to be high in second half of FY2014 as domestic borrowing

nances the decit. In addition, the risk of a rebuild of circular debt in

FY2014 remains high. Public sector development spending was subdued at

PRs243 billion in the rst 6 months of FY2014 and is likely to remainso to

contain the budget decit in light of high current expenditures. This will

have negative implications for long-term investment and growth.

While the governments commitment to severely limit energy

subsidies is underscored by various initial measures, such eforts need

to be more comprehensive. Apart from further price adjustments,

substantial governance reform is needed to reduce theft and losses in

transmission and distribution. Similarly, it will be necessary over the

medium term to change the energy mix through very large investments

in new generation capacity. While these energy measures will help

contain expenditure overruns, eforts to widen the revenue base need to

be accelerated.

3.20.9Fiscal performance

7 of GDP

-J0

0

J0

20

30

R E D D R E R E D R E D R E D

20J0 20JJ 20J2 20J3 20J4

Tax

Net lending

Development

Nontax

External

ank

Nonbank

Current

R = revenue, E = expenditure, D = decit nancing.

Notes: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the

same calendar year. Data refer to consolidated federal and

provincial governments. Net lending includes statistical

discrepancy. Nonbank includes privatization proceeds.

Sources: Ministry of Finance. Pakistan Economic Survey

201213; Pakistan Fiscal Operations JulyJune 201112;

Federal Budget 201314, Budget in Brief; ADB estimates.

Click here for gure data

3.20.8Interest rates

7

6

8

J0

J2

J4

J6

1an

20J4

1ul 1an

20J3

1ul 1an

20J2

1ul 1an

20JJ

Repo rate

Reverse-repo rate

Weighted average lending rate

a

a

On gross disbursements, the amounts disbursed by

banks either in Pakistan rupees or in foreign currency

against loans during the month. It includes loans

repriced, renewed, or rolled over during the month.

Incase of running nance, the disbursed amount means

the maximum amount received by the borrower at any

point during the month.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. http://www.sbp.org.pk

(accessed 14 February 2014).

Click here for gure data

Economic trends and prospects in developing Asia: South Asia Pakistan185

Fiscal devolution under the 18th constitutional amendment in 2011

has made consolidated budget outcomes more dependent on provincial

scal performance. Expenditure containment envisaged under the

federal budget for FY2014 called for a combined provincial budgetary

cash surplus of PRs23.1 billion. Provincial scal operations for the rst

half of FY2014 indicate a consolidated cash surplus for the period, which

needs to be sustained during the second half to meet the scal decit

target for FY2014. Unexpectedly slow progress toward the issuance of

3G spectrum licenses and issues around pending proceeds from telecom

privatization raise concerns over whether these receipts will be realized

during FY2014. Delays in receiving $878 million in CSF receipts could

pose a challenge for the scal target.

To protect the poor from the adverse efects of scal adjustments

and other negative shocks, the federal government is providing cash

transfers through the Benazir Income Support Program to families

identied through a poverty scorecard system. The number of program

beneciaries increased to 4.8 million in FY2013 (Figure 3.20.10).

Thefederal government budget for FY2014 plans to nearly double the

allocation for the program to PRs75 billion. The program has started

piloting a number of additional initiatives for beneciaries, including

health insurance, skills training, loans to develop small businesses, and

primary education co-responsibility cash transfers for children.

Decits in the trade and services accounts worsened with revived

imports and delays in CSF receipts, widening the current account decit

during the rst 7 months of FY2014 to $2.1billion (Figure3.20.11).

Imports grew by 4.2%, compared with negligible growth in the

corresponding period a year earlier, as the textile and power industries

bought machinery. Export growth also picked up to 3.3% in the rst

7months of the scal year, stimulated by 8% growth in textile exports,

which ofset the decline in exports of other manufactures and slow

growth in food exports. All exports are expected to grow further in the

remainder of the scal year, as benets from the Generalized Scheme

of Preferences Plus are realized. With worker remittances showing

a 10.1% increase in the rst 7 months of FY2014, the current account

decit is projected at 1.4% of GDP. Thecurrent account decit for

FY2015 is forecast to be marginally lower at 1.3% of GDP, as lower global

commodity prices partly compensate for higher imports needed to

support the modest pickup in GDP growth.

Key risks emanate from low ofcial foreign exchange reserves

as weak ofcial inows and high debt repayments outweighed IMF

disbursement during the rst half of FY2014. Net foreign direct

investment inows, at $523 million during rst 7 months of FY2014,

were essentially unchanged from a year earlier, and net nancial

account inows totaled only $251 million, though improved from

a slight decit in the earlier period (Figure 3.20.12). Gross ofcial

reserveshaving plunged from $6.0 billion at the end of June 2013 to

$3.1 billion in January 2014, equal to less than 1 month of imports

revived to $3.9billion at the end of February, reecting foreign inows

during thismonth (Figure 3.20.13). The Pakistani rupee appreciated

to PRs100.3 to the dollar, following 6.5% depreciation during the rst

7months of FY2014.

3.20.10Social safety net

Number of

beneciaries

Annual

disbursements

0

20

40

60

0

2

4

6

20J3 20J2 20JJ 20J0 2009

Million PRs billion

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: Ministry of Finance.

Click here for gure data

3.20.11Current account components

Current account

balance

7 of GDP $ million

-J0

-5

0

5

J0

2009 20J0 20JJ 20J2 20J3 1ul-1an

20J3

1ul-1an

20J4

Current transfers

Trade balance

Income

Services

-30

-J5

0

J5

30

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data. http://

www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 3 March 2014).

Click here for gure data

3.20.12 Net foreign direct investment

portfolio, and financial account

(flows)

$ billion

2007 2008 2009 20J0 20JJ 20J2 20J3 1ul-1an

20J3

1ul-1an

20J4

-3

0

3

6

9

J2

Portfolio

Direct

Financial account

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data.

http://www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 17 February 2014).

Click here for gure data

186Asian Development Outlook 2014

Policy challengeachieving scal sustainability

Achieving scal sustainability is a major recurring challenge for

policy makers in Pakistan. Fiscal discipline has eroded in recent

years with the persistent need to nance expanding energy sector

subsidies, worseninglosses incurred by state-owned enterprises, and

highexpenditures for security.

Tax collected by the Federal Board of Revenue stood at 8.5% of GDP

in FY2013, one of the lowest collection ratios in the region that reects

structural and administrative issues. As a result, spending for badly

needed infrastructure has relied largely on foreign inows. Additional

spending requirements have emanated from natural disasters in the past

few years, as well from the need to establish social safety nets. Higher

scal decits and very limited foreign inows during the past 2years

have signicantly increased short-term domestic borrowing, causing

interest payments to balloon. Moreover, high governmentborrowing

from commercial banks contributes to low private sector credit.

The domestic portion of public debt increased sharply for the second

year in a row, from 38.0% of GDP at the end of FY2012 to 41.5% in

FY2013, to nance high scal decits (Figure 3.20.14). Foreign debt fell

by 4.6% of GDP in FY2013, mainly as IMF debt was repaid. Total public

debt (including external liabilities) at the end of FY2013 amounted to

63.3% of GDP, exceeding the legal limit of 60% set under the Fiscal

Responsibility Debt Limitation Act, 2005. Although a generally favorable

negative diferential between real interest rates and GDP growth has

eroded the real value of government debt, growth in the primary decit

would endanger debt sustainability.

The federal government is implementing its scal framework

under the IMFs 3-year program. Immediate measures afecting the

federalbudget for FY2014 pertain to raising the general sales tax rate

and certain power tarifs to contain subsidies. Structural reforms

to widen the revenue base are, however, critical for restoring scal

sustainability. These include improving tax administration, eliminating

exemptions to certain sectors, and bringing all sectors including

agriculture under the tax net. Eforts would be required from federal

and provincial governments alike, as some taxes (notably on agriculture)

fall under provincial administration and reforms would help enhance

provincial revenues. Currently, over 90% of provincial revenues are

transfers of federal shared taxes. As provinces have assumed a greater

share of federal resources and spending responsibilities through

devolution, their scal performance has become even more important

toward achieving national scal outcomes. For instance, collecting

sales tax on services is now a provincial government responsibility, and

most social sector responsibilities have been transferred to provinces.

Clearly, the allocation of 57.7% of the national shared tax base to

provinces determined under the 2010 National Finance Commission

award requires greater scal prudence and discipline on the part of the

provinces. A mechanism to ensure provincial scal discipline is likely to

be a crucial consideration in upcoming discussions for the 2015 award.

3.20.14 Domestic and external debt

7 of GDP

0

20

40

60

80

20J3 20J2 20JJ 20J0 2009

Domestic

External

Note: Years are scal years, ending on 30 June of the same

calendar year.

Source: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data. http://

www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 17 February 2014).

Click here for gure data

3.20.13 Foreign reserves and exchangerate

Reserves

$ billion PRsj$

JJ0

J00

90

80

70

0

5

J0

J5

20

Feb

20J4

1un

20J3

Dec 1un

20J2

Dec 1un

20JJ

PRsj$

Sources: State Bank of Pakistan. Economic Data. http://

www.sbp.org.pk (accessed 2 September 2013); CEIC Data

Company (accessed 6 March 2014).

Click here for gure data

You might also like

- Fiscal Situation of PakistanDocument9 pagesFiscal Situation of PakistanMahnoor ZebNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy Statement September 2013 HighlightsDocument42 pagesMonetary Policy Statement September 2013 HighlightsScorpian MouniehNo ratings yet

- Brief Survey of Pakistan Economy 2014Document2 pagesBrief Survey of Pakistan Economy 2014Ahmed RazaNo ratings yet

- Article On Year End Assessment OCE PS SBED2Document13 pagesArticle On Year End Assessment OCE PS SBED2Zayrel CasiromanNo ratings yet

- Snapshot of Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument53 pagesSnapshot of Bosnia and HerzegovinaDejan ŠešlijaNo ratings yet

- MPS Aug 2022 EngDocument3 pagesMPS Aug 2022 EngHassaan AhmedNo ratings yet

- RBI Annual Report Highlights Key Risks to India's 8.5% GDP GrowthDocument5 pagesRBI Annual Report Highlights Key Risks to India's 8.5% GDP GrowthSmriti KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Economic Outlook: Table 1.1: Macroeconomic IndicatorsDocument9 pagesEconomic Outlook: Table 1.1: Macroeconomic IndicatorsBilal SolangiNo ratings yet

- Adb2014 Sri LankaDocument5 pagesAdb2014 Sri LankaRandora LkNo ratings yet

- State of EconomyDocument21 pagesState of EconomyHarsh KediaNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy of Pakistan: Submitted To: Mirza Aqeel BaigDocument9 pagesMonetary Policy of Pakistan: Submitted To: Mirza Aqeel BaigAli AmjadNo ratings yet

- DirectorDocument49 pagesDirectorrohitkoliNo ratings yet

- Army Institute of Business Administration: Savar Cantonment, DhakaDocument6 pagesArmy Institute of Business Administration: Savar Cantonment, DhakaN. MehrajNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Economic Brief 2012 May 31Document18 pagesBangladesh Economic Brief 2012 May 31Mohammad MynoddinNo ratings yet

- India Union Budget 2013 PWC Analysis BookletDocument40 pagesIndia Union Budget 2013 PWC Analysis BookletsuchjazzNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Fiscal Performance and Economic Outlook During COVID-19Document8 pagesPakistan's Fiscal Performance and Economic Outlook During COVID-19sam dinNo ratings yet

- State of The Economy: Executive SummaryDocument8 pagesState of The Economy: Executive SummaryFarrukh SohailNo ratings yet

- Tate Ank of Akistan: Onetary Olicy OmmitteeDocument2 pagesTate Ank of Akistan: Onetary Olicy Ommitteebrock lesnarNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument14 pagesAssignmentaliraza786kalhoroNo ratings yet

- Government Expenditures of PakistanDocument19 pagesGovernment Expenditures of PakistanHamza ShafiqNo ratings yet

- MPD 24 May English)Document3 pagesMPD 24 May English)Aazar Aziz KaziNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Quarterly Economic Update - March 2012Document28 pagesBangladesh Quarterly Economic Update - March 2012Asian Development BankNo ratings yet

- State of The Economy 2011Document8 pagesState of The Economy 2011agarwaldipeshNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs A3Document29 pagesCurrent Affairs A3AHSAN ANSARINo ratings yet

- State of The Economy: Executive SummaryDocument11 pagesState of The Economy: Executive Summaryshahzad khalidNo ratings yet

- RBI Governor Statement 1702090413Document9 pagesRBI Governor Statement 1702090413Jyotiraditya JadhavNo ratings yet

- NIFK16289689Document28 pagesNIFK16289689Yuki TakenoNo ratings yet

- 08 Trade and PaymentsDocument27 pages08 Trade and PaymentsMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Press 20140408eaDocument7 pagesPress 20140408eaRandora LkNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey Report 2018-19Document19 pagesEconomic Survey Report 2018-19sania.maharNo ratings yet

- Pak Economy Overview: Growth, Challenges & OutlookDocument58 pagesPak Economy Overview: Growth, Challenges & OutlookTalha AsifNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics. AssignmentDocument18 pagesMacroeconomics. Assignmentsayda tahmidaNo ratings yet

- India Development Update - World Bank November 2022Document44 pagesIndia Development Update - World Bank November 2022Kislay KanthNo ratings yet

- Vision: Personality Test Programme 2019Document5 pagesVision: Personality Test Programme 2019sureshNo ratings yet

- Philippines Market Overview Despite COVID ImpactDocument25 pagesPhilippines Market Overview Despite COVID ImpactRowena TesorioNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy Statement: State Bank of PakistanDocument32 pagesMonetary Policy Statement: State Bank of Pakistanbenicepk1329No ratings yet

- Executive Summery - English-2020Document9 pagesExecutive Summery - English-2020M Tariqul Islam MishuNo ratings yet

- World Bank 2023 India ReportDocument27 pagesWorld Bank 2023 India ReportMithilesh KumarNo ratings yet

- MSR April 2016Document25 pagesMSR April 2016Sharjil HaqueNo ratings yet

- Economics GNP MalaysiaDocument14 pagesEconomics GNP Malaysiakayrul700% (1)

- Equity Valuation of MaricoDocument18 pagesEquity Valuation of MaricoPriyanka919100% (1)

- CHP 1Document13 pagesCHP 1Gulfishan MirzaNo ratings yet

- Union Budget 2023Document13 pagesUnion Budget 2023RomaNo ratings yet

- China's Economic Trend Under The Impact of The EpidemicDocument10 pagesChina's Economic Trend Under The Impact of The EpidemicRumi AzhariNo ratings yet

- Getting To The Core: Budget AnalysisDocument37 pagesGetting To The Core: Budget AnalysisfaizanbhamlaNo ratings yet

- Premia Insights Feb2020 PDFDocument6 pagesPremia Insights Feb2020 PDFMuskan mahajanNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument13 pagesAssignmentaliraza786kalhoroNo ratings yet

- GDP Fy14 Adv Est - 7 Feb 2014Document4 pagesGDP Fy14 Adv Est - 7 Feb 2014mkmanish1No ratings yet

- Pakistan's Economy Sees 5.37% Growth in 2020-21 With Industrial Sector Leading RecoveryDocument4 pagesPakistan's Economy Sees 5.37% Growth in 2020-21 With Industrial Sector Leading RecoveryShahab MurtazaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Economic ReviewDocument3 pagesPakistan Economic Reviewanum khurshidNo ratings yet

- Balance of Payments: 2. InflationDocument3 pagesBalance of Payments: 2. InflationKAVVIKANo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Quarterly Economic Update - September-December 2012Document29 pagesBangladesh Quarterly Economic Update - September-December 2012Asian Development BankNo ratings yet

- Alhamra Islamic Income FundDocument28 pagesAlhamra Islamic Income FundARquam JamaliNo ratings yet

- Final Exam 13574 PDFDocument5 pagesFinal Exam 13574 PDFHome PhoneNo ratings yet

- Focus WritingsDocument14 pagesFocus WritingsSumaiya AfrojNo ratings yet

- PR 15 May 20 PDFDocument3 pagesPR 15 May 20 PDFHira RasheedNo ratings yet

- India ForecastDocument10 pagesIndia Forecastmalikrocks3436No ratings yet

- Kinh Te 2013-2014Document2 pagesKinh Te 2013-2014Olivia TranNo ratings yet

- Global Economic Scenario and About State Bank of India Work With Msme SBIDocument21 pagesGlobal Economic Scenario and About State Bank of India Work With Msme SBIkrishnanshu sarafNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Quarterly Economic Update: September 2014From EverandBangladesh Quarterly Economic Update: September 2014No ratings yet

- Cem Indu PlayerDocument1 pageCem Indu PlayerAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- MKT Pulse - KOHC - Raise TP On Incorporation of Expansion Buy 07-03-2018Document4 pagesMKT Pulse - KOHC - Raise TP On Incorporation of Expansion Buy 07-03-2018Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- 2013 FRM Practice Exam PDFDocument74 pages2013 FRM Practice Exam PDFAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- 2017 FRM Study GuideDocument24 pages2017 FRM Study GuideDuc AnhNo ratings yet

- Imtiaz Supermarket PVT LTD in Retailing (Pakistan)Document5 pagesImtiaz Supermarket PVT LTD in Retailing (Pakistan)Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Finance Bill Highlights 2014Document58 pagesFinance Bill Highlights 2014Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- ADP 2016-21 (New)Document66 pagesADP 2016-21 (New)Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Development Update0April02014Document27 pagesPakistan Development Update0April02014Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Finals 2014Document1 pageSyllabus For Finals 2014Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument8 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Target Audience? Media Personalities Dos and Don'ts: Positive To Do ListDocument1 pageTarget Audience? Media Personalities Dos and Don'ts: Positive To Do ListAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Submission Worksheet - TemplateDocument2 pagesAssignment Submission Worksheet - TemplateAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Aqualisa Quartz Case StudyDocument4 pagesAqualisa Quartz Case Studyeyecandy4100% (1)

- SC Closing ProgramDocument3 pagesSC Closing ProgramAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Artcl Summry BhattiDocument1 pageArtcl Summry BhattiAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Man Acc Ass1Document3 pagesMan Acc Ass1Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Vs LatitudinalDocument1 pageLongitudinal Vs LatitudinalAbdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- Acc Asg3Document1 pageAcc Asg3Abdul Ghaffar BhattiNo ratings yet

- NGPF - Annual Report 12Document103 pagesNGPF - Annual Report 12freemind3682No ratings yet

- Chapter 13 - Decision AnalysisDocument31 pagesChapter 13 - Decision AnalysisOfelia RagpaNo ratings yet

- Updates On Open Offer (Company Update)Document53 pagesUpdates On Open Offer (Company Update)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- Letter To Commissioner Reardon Regarding Unemployment Benefits OverpaymentsDocument2 pagesLetter To Commissioner Reardon Regarding Unemployment Benefits OverpaymentsState Senator Liz KruegerNo ratings yet

- Bao Cao N100 91332-06020Document2 pagesBao Cao N100 91332-06020anhthoNo ratings yet

- Ha Joon Chang Industrial Policy 2020Document28 pagesHa Joon Chang Industrial Policy 2020Liber Iván León OrtegaNo ratings yet

- GA55Document2 pagesGA55Rajneesh Khichar : MathematicsNo ratings yet

- Importance of Spindle Speed in Ring Frame: Research Article ISSN: 2637-4595Document3 pagesImportance of Spindle Speed in Ring Frame: Research Article ISSN: 2637-4595Arif HasanNo ratings yet

- CLASS-X Unit 5 Green Skills ASSESSMENTDocument4 pagesCLASS-X Unit 5 Green Skills ASSESSMENTDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- IDFC Bank StatementDocument2 pagesIDFC Bank StatementSURANA197367% (3)

- Philippine Business Course SyllabusDocument11 pagesPhilippine Business Course SyllabusJerrick Ivan YuNo ratings yet

- Montenegro Investment OpportunitiesDocument41 pagesMontenegro Investment Opportunitiesassassin011No ratings yet

- Andrea Orders PDFDocument2 pagesAndrea Orders PDFMoonlight SquadNo ratings yet

- Bradford T (2018) - The Energy System Technology Economics Markets and Policy - TOCDocument12 pagesBradford T (2018) - The Energy System Technology Economics Markets and Policy - TOCArif GokakNo ratings yet

- Revision Public FinanceDocument23 pagesRevision Public Financekareem kareem100% (2)

- Totem Thread CatalogueDocument28 pagesTotem Thread CataloguePushpender SinghNo ratings yet

- 13 RevisedDocument3 pages13 RevisedSathya Kanth KanyagariNo ratings yet

- Trading Results For Day 4 - 25 May 2020Document2 pagesTrading Results For Day 4 - 25 May 2020David ShimNo ratings yet

- Philippines Capital Gains Tax Return Form 1707Document2 pagesPhilippines Capital Gains Tax Return Form 1707Anne VallaritNo ratings yet

- Transformation of Organization The Strategy of Change ManagementDocument23 pagesTransformation of Organization The Strategy of Change ManagementMohamad Nurreza RachmanNo ratings yet

- Applications of Diferentiation: Using Differentials and DerivativesDocument32 pagesApplications of Diferentiation: Using Differentials and DerivativesMajak MarialNo ratings yet

- Saxo Outrageous PredictionsDocument26 pagesSaxo Outrageous PredictionsZerohedge75% (4)

- Steel CH 1Document34 pagesSteel CH 1daniel workuNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice: Full File at Https://testbankuniv - eu/International-Economics-12th-Edition-Salvatore-Test-BankDocument9 pagesMultiple Choice: Full File at Https://testbankuniv - eu/International-Economics-12th-Edition-Salvatore-Test-BankalliNo ratings yet

- ALLIED-Weekly-Market-Report 23 08 2020Document12 pagesALLIED-Weekly-Market-Report 23 08 2020Supreme starNo ratings yet

- Raxit Parmar - CVDocument2 pagesRaxit Parmar - CVRaxit PaRmarNo ratings yet

- Cost ObjectiveDocument5 pagesCost ObjectiveKarmen ThumNo ratings yet

- Impact of Micro FinanceDocument61 pagesImpact of Micro FinancePerry Arcilla SerapioNo ratings yet

- NEVADA INDEPENDENT - 2019.08.08 - Appendix To Petition Writ Mandamus FiledDocument218 pagesNEVADA INDEPENDENT - 2019.08.08 - Appendix To Petition Writ Mandamus FiledJacob SolisNo ratings yet

- Social, Economic and Political Thought Notes Part III (ADAM SMITH, DAVID RICARDO, KARL MARX, MAX WEBER, EMILE DURKHEIM)Document3 pagesSocial, Economic and Political Thought Notes Part III (ADAM SMITH, DAVID RICARDO, KARL MARX, MAX WEBER, EMILE DURKHEIM)simplyhueNo ratings yet