Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anthony Fontana-Modesto Is A Freelance Journalist Who Writes On Leftist and

Uploaded by

Marc Allen HerbstOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anthony Fontana-Modesto Is A Freelance Journalist Who Writes On Leftist and

Uploaded by

Marc Allen HerbstCopyright:

Available Formats

man, a man who was full of contradictions, a man who was so right, and, in some

ways, so wrong about the nature of the times we are living in. As such, this book

quite sufciently fullls its goal, which is, according to Jan Willem Stutjes

preface, . . . to explore frankly and freely the life and work of Ernest Mandel, a

Flemish revolutionary Marxist with whose ideas I feel a close afnity (Preface,

xv). Stutje fullls well indeed the goal he set out for himself. It is perhaps the

books harmonious balance between historical and political preciseness with a

meticulously detailed account of Mandels life that makes this an invaluable and

stimulating work. This is a clear, concise, and riveting account of one of the most

dynamic political gures in world history. This book should not only be read by

a new generation of Marxists, economists, sociologists, and economic historians.

It should also be read by a new generation of young people who refuse to give

up hope in the future of our species and in the possibility of changing the world

we live in.

Anthony Fontana-Modesto is a freelance journalist who writes on leftist and

socialist history and currents. He is a researcher at the Labor Policy Institute of

Brooklyn College Graduate Center for Worker Education. He recently com-

pleted a manuscript on the Bolivarian experiment in participatory democracy in

Venezuela. Address correspondence to A. Fontana-Modesto, Brooklyn College,

City University of New York, 25 Broadway, 7th Floor, New York, New York

10004. Email: afmodesto@yahoo.com. Telephone: +011-212-966-4014.

Sen, Rinku with Mamdouh, Fekkak. The Accidental American: Immigration and Citizenship in the

Age of Globalization. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2008. 248 pp. US$24.95

(hardcover).

In the days after September 11, 2001, a panic-ridden city rounded up the

usual suspects. Those not here legally were looked at with suspicion. A pizza

delivery guy in my neighborhood who had come from Egypt and lived here for

two decades was arrested, taken away from his family to be questioned. Undocu-

mented immigrants were detained, many without access to lawyers or informa-

tion about the charges against them. Although the legal principal of habeas

corpus has been around since the Magna Carta of 1215, the U.S. government

saw t to do away with it after 9/11. The effort to detail suspected immigrants

was the beginning of a policy shift toward the criminalization rather than

amnesty for undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Over the next decade, this

policy shift impacted immigrants and undocumented workers in countless ways,

often separating them from their families and communities. Yet, as Rinku Sen

and Fekkak Mamdouh highlight in The Accidental American, many fought back.

On January 26, 2002, a group of activists and civil libertarians, including

attorney Norm Siegel, converged for a picket at the Metropolitan Detention,

Sunset Park in Brooklyn. Tell us the charges! and Who is being held read

439

their signs. The protest addressed the round-up of immigrants, many held

without charges or access to lawyers after the terrorist attacks the previous fall.

On April 10, 2006, half a million activists clogged the streets of downtown Los

Angeles, calling for dignity and human rights for immigrants. The sitting mayor

addressed the crowd, insisting that no one is illegal. That year, 195,024

immigrants were deported and the New York Times reported that the prison

business stood to prot if immigration reform determined that more immi-

grants could be held indenitely.

On May 1, 2007, the Los Angeles Police Department red pepper spray on

a May Day rally for workers and immigrants the following spring. Police Com-

missioner was later forced to apologize in order to keep his job.

On November 4, 2008, a group of activists were arrested at the entrances of

the Immigrant Customs Enforcement (ICE) building in San Francisco. The goal

of their action was to stop the ICE raids. That year, some 349,041 immigrants,

nearly double that of the previous year, were departed as result of the policy.

Activists argued that the policy violated the basic human rights of those

detained, separating families and leaving children in limbo, some in dangerous

private detention centers, isolated from lawyers, family, or community support.

On January 31, 2009, a controversy over the treatments of inmates awaiting

deportation from a private prison, the Reeves County Detention Facility in

West, Texas, sparked a riot when prisoners asked for medical attention. The

inmate was dying.

On March 7, 2009, Rev. Billy and the Life after Shopping Gospel Choir

sang, We Dance the Day You Are Free outside the Varick Street Special

Processing Center, holding immigrants detained during the raids. The building

is a detention center of the ICE, Immigrant Correction Enforcement, an

Orwellian development from 9/11 and the torture years of Bush Cheney. But

here in our special city, New York, the rev sermonized. We have to stop

beating people up in the name of 9/11, he screamed, his face turning red.

Standing in front of the innocuous-looking building, onlookers decried the

use of private detention centers and the prot motive behind the ongoing arrests

and indenite incarcerations.

On May 2, 2009, opponents of immigration reform charged that immigrants

carry disease and spread swine u as an argument against policy reform.

On May 6, 2009, immigrant advocates staged an act of civil disobedience

over the deportation of family members at the ICE building in Bloomington,

Illinois. The action was in response to the ongoing raids, imprisonment, and

deportations and violations of the human rights among those detained, many

documented in Amnesty Internationals report Jailed without Justice: Immigra-

tion Detention in the USA. The action was not unprecedented. Similar actions,

in addition to hunger strikes, have been held in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and

New York earlier in the year. All were organized with the goal of ending the raids

and deportations.

Gradually, states embraced more extreme solutions to the competing

demands of the immigration policy gap. By April of 2010, the state of Arizona

440 WORKINGUSA: THE JOURNAL OF LABOR AND SOCIETY

passed a draconian law, SB 1070, giving way for law enforcement to stop and ask

for papers for anyone they suspected of being undocumented. Calls for boycotts

started almost immediately. Mayday rallies the following month condemned the

measure and called for solidarity among immigrants and workers.

Such are the sites and sounds of the post-9/11 immigration debate, the latest

chapter in a generations-old controversy over the rightful place of immigrants in

the U.S. As these ashpoints suggest, the topic increasingly eludes a public

consensus. In its void, a new generation of Know Nothings scream; stopgap

policies including raids, deportations, and a Berlin-like wall along the U.S.

Mexico border ignite emotions without grappling with the complexity of the

situation. Its the criminalization of immigrants, explains Alfredo Gonzales, a

Latino studies professor at NYU, in the Indypendent. While advocates hope for

a program that includes a practical route toward citizenship for undocumented

workers, opponents push to demonize those hoping to do what immigrants

coming to this country have accomplished since the colonial era. Caught in the

middle are undocumented workers doing the heavy lifting.

One way to situate this unfortunate turn in U.S. immigration policy is to

read The Accidental American by Rinku Sen and organizer Fekkak Mamdouh.

The book contributes to an already expanding body of literature on immigra-

tion, migration, and labor including Illegal People: How Globalization Creates

Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants by David Beacon and Escape Routes:

Control and Subversion in the 21st Century by Dimitris Papadopoulos, Niamh

Stephenson, and Vassilis Tsianos. All deal with the complicated interplay

between globalization of commerce, migration of bodies, and the ever increasing

imperative of workers to organize to protect their own interests, whether in a

union or not. While immigrants have long been viewed as a source of exible

labor, today, transnational workers face an array of barriers. Obstacles range

from the demonization of those without their papers to a neoliberal turn in

global labor markets, rapidly altering the very nature of work. Neoliberalism

refers to an ideology that advocates expanding global free trade and competition

and withdrawing the state from regulating economic activity; the result is the

deregulation of basic living standards among the poor and working class, notes

Immanuel Ness in Immigrants, Unions, and the New US Labor Market (2) an

ethnography about the Green Grocer workers in New York City. Faced with

ever decreasing wages in a global race to the bottom in terms of labor standards,

workers are forced to leave their homes in search of work. When they arrive

here, many are viewed as threats. Faced with these challenges, immigrant

workers are doing what they have always done. Instead of perish, they are getting

organized.

Enter Mamdouh Fekkak, the subject of The Accidental American who was one

such worker at Windows on the World, a restaurant lost to the 2001 terrorist

attacks in NY. Mamdouh Fekkak is the co-founder of Restaurant Opportunities

Center of New York (ROC-NY) and co-director of Restaurant Opportunities

Center United, the countrys rst national restaurant worker organization.

Rinku Sen is president and executive director of the Applied Research Center

441

and the publisher of ColorLines magazine. She is the author of Stir It Up: Lessons

in Community Organizing and Advocacy, a popular and pulsing work on organiz-

ing methods, theory, and practice. As a follow-up to Stir It Up, Sen set her eyes

on organizing among vulnerable populations taking place in the U.S. after 9/11,

her focus, immigrant workers, many undocumented, who lost their jobs after the

Windows on the World Restaurant perished. The government treated the

situation as a temporary emergency, but what Windows workers really wanted

was a political shift, explains Sen in the works second chapter, US and them

after 9/11. [T]he occasional job training or cash assistance would make no

long-term difference in their unstable lives. Rather than therapy or short-term

solutions, what these unemployed workers needed were jobs, housing, health

care, and legalizationthese were needs that therapy and pills couldnt meet

(423).

Through The Accidental American, Sen traces the stories of workers including

Fekkak Mamdouh. Without a job, Mamdouh was forced to grapple with an

anti-immigrant sentiment that gripped the country after the attacks. US history

is full of attempts to exclude people who did not seem at the time to the image

of a real American, writes Sen (51). [T]he treatment of immigrants has always

been racialized, Sen elaborates, highlighting a key theme of post-9/11 political

culture, as race and otherness overlap into an anti-immigrant, anti-terror panic.

Over the years racial hierarchies have shifted and racialized denitions changed

as European immigrants gained status while Mexican and Third World immi-

grants did not (51). After 9/11, immigrants who had once been welcomed were

viewed with suspicion and hostility. Facing increasing hostilities, Mamdouh did

what people often do when pushed into a corner. He pushed back, organizing to

form ROC-NY. The organizations aim was to assist immigrant workers and

ght for work, civil liberties, and dignity as human beings, and they did it by

building a network of those affected by both the loss of their jobs after 9/11.

Here, ROC-NY helped immigrant and native-born workers nd common cause

around the conditions of their labor. Since it was founded in 2002, it has won a

number of campaigns against restaurant corporations totaling some US$4.5 in

back wages for and discrimination payments for immigrant workers, all while

helping a group of workers to start a cooperative restaurant. Today, ROC has

built a membership base of some 2,000 workers, and in so doing, ROC-NY has

become a model.

Throughout The Accidental American, Sen points us to the inner workers of

a campaign of those pushed to the edge of history and the global economy.

Squeezed by global factors ranging from neoliberalism to the war on terror, she

highlights the stories of how workers organize to nd a place for themselves to

work and thrive. Along the way, Mamdouh comes to see himself following in the

tradition of Ceasar Chavez. Yet, instead of championing the farm workers as the

National Farm Worker Association once did, Mamdouh helped organize a

group of immigrant workers in the restaurant industry. Grappling with both

economic marginalization and social stigma, the similarities between the groups

are many.

442 WORKINGUSA: THE JOURNAL OF LABOR AND SOCIETY

In highlighting their stories, Sen frames a discussion on the limitations of

current approaches to immigration policy and the hysteria that often accompa-

nies it. She acknowledges some of the charges against immigrants hold a grain of

truthmany are undocumented. Others are patently false, notes Sen (66).

Immigration law was discriminatorily created and applied; wages are driven

down largely because the United States wont enforce its own labor laws; immi-

grants, even the vast majority of undocumented immigrants, do pay taxes. And

there has been no sign that restricting immigration will have any effect on

preventing terrorism, (66) (for a useful overview of the lack of enforcement of

U.S. labor laws around exploitation of migrant workers, see In Strawberry

Fields, a chapter in Eric Schlossers 2003 Reefer Madness: Sex, Drugs, and Cheap

Labor in the American Black Market).

Sen and Mamdouh call for a more coherent, human rights-based approach

to reform of U.S. immigration policy. In this way, bodies move across borders as

freely as ideas as possibilities, beneting both workers and the demand for labor.

Most of all, this alternative policy approach is based on the lessons of the

organizing experience of immigrant workers. Through Mamdouhs story, we

witness a redemptive narrative of labor of immigration and citizenship. Every

person has dignity, yet people gain power when they organize and collectively

push U.S. public opinion and politicians to incorporate their perspectives. This

only comes through creativity and action. Faced with a vexing challenge,

Mamdouh organized himself out of a corner for a common good. Through

Mamdouhs story, Sen highlights the innovative organizing born of the post-

9/11 immigrant debate. The response to this ugly moment points to a way out

our current impasse.

Benjamin Shepard, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Human Service at New York

School of Technology/City University of New York. As a social worker,

he worked in AIDS housing settings from San Francisco to Chicago to New

York, where he directed the start ups for two congregate housing programs for

people with HIV/AIDS. He is author of Queer Political Performance and Protest

(Routledge 2009); White Nights and Ascending Shadows: An Oral History of the San

Francisco AIDS Epidemic (Cassell 1997) among many other books, articles and

chapters. Address correspondence to Benjamin H. Shepard, City Tech/CUNY,

300 Jay Street N-401, Brooklyn, NY 11201. Telephone: +011-718-260-5135.

E-mail: bshepard@citytech.cuny.edu.

Seniors, Paula Marie. Beyond Lift Every Voice and Sing: The Culture of Uplift, Identity, and Politics

in Black Musical Theater. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2009. 368 pp. $54.95

(hardcover).

Treading along the path blazed by David Krasner in Resistance, Parody, and

Double Consciousness, the award-winning study of African-American theater

443

You might also like

- Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First CenturyFrom EverandBans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First CenturyNo ratings yet

- The Chicken Trail: Following Workers, Migrants, and Corporations across the AmericasFrom EverandThe Chicken Trail: Following Workers, Migrants, and Corporations across the AmericasRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Rallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaFrom EverandRallying for Immigrant Rights: The Fight for Inclusion in 21st Century AmericaNo ratings yet

- Governing Immigration Through Crime: A ReaderFrom EverandGoverning Immigration Through Crime: A ReaderJulie A. DowlingNo ratings yet

- American Immigration After 1996: The Shifting Ground of Political InclusionFrom EverandAmerican Immigration After 1996: The Shifting Ground of Political InclusionNo ratings yet

- Immigration Matters: Movements, Visions, and Strategies for a Progressive FutureFrom EverandImmigration Matters: Movements, Visions, and Strategies for a Progressive FutureNo ratings yet

- Detention Empire: Reagan's War on Immigrants and the Seeds of ResistanceFrom EverandDetention Empire: Reagan's War on Immigrants and the Seeds of ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Robber Barons and Wretched Refuse: Ethnic and Class Dynamics during the Era of American IndustrializationFrom EverandRobber Barons and Wretched Refuse: Ethnic and Class Dynamics during the Era of American IndustrializationNo ratings yet

- Open Borders Inc.: Who's Funding America's Destruction?From EverandOpen Borders Inc.: Who's Funding America's Destruction?Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Presente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialFrom EverandPresente!: Latin@ Immigrant Voices in the Struggle for Racial Justice / Voces Inmigranted Latin@s en la Lucha por la Justicia RacialNo ratings yet

- Workers Vanguard No 851 - 08 July 2005Document16 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 851 - 08 July 2005Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- Those Who Know Don't Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral StateFrom EverandThose Who Know Don't Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral StateNo ratings yet

- All-American Nativism: How the Bipartisan War on Immigrants Explains Politics as We Know ItFrom EverandAll-American Nativism: How the Bipartisan War on Immigrants Explains Politics as We Know ItRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Making of Law: The Supreme Court and Labor Legislation in Mexico, 1875–1931From EverandThe Making of Law: The Supreme Court and Labor Legislation in Mexico, 1875–1931No ratings yet

- The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation, Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Anti-Slavery Project: From the Slave Trade to Human TraffickingFrom EverandThe Anti-Slavery Project: From the Slave Trade to Human TraffickingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Asylum Denied: A Refugee’s Struggle for Safety in AmericaFrom EverandAsylum Denied: A Refugee’s Struggle for Safety in AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawFrom EverandThe Immigration Crucible: Transforming Race, Nation, and the Limits of the LawNo ratings yet

- Responding to Human Trafficking: Sex, Gender, and Culture in the LawFrom EverandResponding to Human Trafficking: Sex, Gender, and Culture in the LawNo ratings yet

- You Can't Say That!: The Growing Threat to Civil Liberties from Antidiscrimination LawsFrom EverandYou Can't Say That!: The Growing Threat to Civil Liberties from Antidiscrimination LawsNo ratings yet

- Workers Vanguard No 649 - 02 August 1996Document16 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 649 - 02 August 1996Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on CrimeFrom EverandIn the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on CrimeNo ratings yet

- A Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate EveryoneFrom EverandA Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate EveryoneNo ratings yet

- On Transits and Transitions: Trans Migrants and U.S. Immigration LawFrom EverandOn Transits and Transitions: Trans Migrants and U.S. Immigration LawNo ratings yet

- Deported Immigrant Policing Disposable Labor and Global CapitalismDocument316 pagesDeported Immigrant Policing Disposable Labor and Global Capitalismmsadooq0% (1)

- Taking a Stand: The Evolution of Human RightsFrom EverandTaking a Stand: The Evolution of Human RightsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Resonant Violence: Affect, Memory, and Activism in Post-Genocide SocietiesFrom EverandResonant Violence: Affect, Memory, and Activism in Post-Genocide SocietiesNo ratings yet

- Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S.From EverandInside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S.No ratings yet

- Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican MigrationFrom EverandUndocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican MigrationNo ratings yet

- I Can't Breathe: How a Racial Hoax Is Killing AmericaFrom EverandI Can't Breathe: How a Racial Hoax Is Killing AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (13)

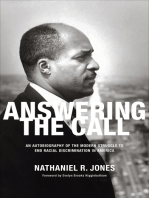

- Answering the Call: An Autobiography of the Modern Struggle to End Racial Discrimination in AmericaFrom EverandAnswering the Call: An Autobiography of the Modern Struggle to End Racial Discrimination in AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Violence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the CentaurFrom EverandViolence, Coercion, and State-Making in Twentieth-Century Mexico: The Other Half of the CentaurNo ratings yet

- Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of SlaveryFrom EverandMaking Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of SlaveryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Human Rights and Humanitarian Intervention: Legitimizing the Use of Force since the 1970sFrom EverandHuman Rights and Humanitarian Intervention: Legitimizing the Use of Force since the 1970sNo ratings yet

- The Nationalist Revival: Trade, Immigration, and the Revolt Against GlobalizationFrom EverandThe Nationalist Revival: Trade, Immigration, and the Revolt Against GlobalizationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Exiled in America: Life on the Margins in a Residential MotelFrom EverandExiled in America: Life on the Margins in a Residential MotelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Invasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, And Other Foreign Menaces To Our ShoresFrom EverandInvasion: How America Still Welcomes Terrorists, Criminals, And Other Foreign Menaces To Our ShoresRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (10)

- Immigration and the Border: Politics and Policy in the New Latino CenturyFrom EverandImmigration and the Border: Politics and Policy in the New Latino CenturyNo ratings yet

- Manifest Destinies, Second Edition: The Making of the Mexican American RaceFrom EverandManifest Destinies, Second Edition: The Making of the Mexican American RaceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Downplaying Deportations How Textbooks Hide The Mass Expulsion of Mexican Americans During The GreatDocument5 pagesDownplaying Deportations How Textbooks Hide The Mass Expulsion of Mexican Americans During The GreatNoah Bardach100% (1)

- Index of Abstracts v4 Historical MaterialismDocument209 pagesIndex of Abstracts v4 Historical MaterialismfklacerdaNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument9 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-271755976No ratings yet

- Playing Global Cop: Militarism and The Prison-Industrial ComplexDocument7 pagesPlaying Global Cop: Militarism and The Prison-Industrial ComplexsherahfaulknerNo ratings yet

- FIELD 01 Herbst CulturalPolicyOfFailedStateDocument16 pagesFIELD 01 Herbst CulturalPolicyOfFailedStateMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2011 SillyDocument4 pages2011 SillyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2012 OccupyagainstDocument5 pages2012 OccupyagainstMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Query SheetDocument12 pagesBook Review: Query SheetMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Reflections Reflections: Narrative IN Social: Turn WorkDocument3 pagesReflections Reflections: Narrative IN Social: Turn WorkMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Direct Action: Kelly Moore and Benjamin ShepardDocument5 pagesDirect Action: Kelly Moore and Benjamin ShepardMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2011 MovingpoliticsreviewDocument6 pages2011 MovingpoliticsreviewMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Commentary Labor and Occupy Wall Street: Common Causes and Uneasy AlliancesDocument14 pagesCommentary Labor and Occupy Wall Street: Common Causes and Uneasy AlliancesMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2010 SyringeexchangeDocument5 pages2010 SyringeexchangeMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Teaching Community Projects: Benjamin Shepard, Ph.D. New York College of Technology/City University of New YorkDocument7 pagesTeaching Community Projects: Benjamin Shepard, Ph.D. New York College of Technology/City University of New YorkMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2010 RofesDocument33 pages2010 RofesMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2010 PlayandDocument22 pages2010 PlayandMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Responding To Harvey: It's All About Organizing: Benjamin ShepardDocument11 pagesResponding To Harvey: It's All About Organizing: Benjamin ShepardMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Lambda Literary: Harvey Milk & The Politics of Neighborhood LifeDocument7 pagesLambda Literary: Harvey Milk & The Politics of Neighborhood LifeMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 TreatmentDocument2 pages2009 TreatmentMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 MilkreviewDocument4 pages2009 MilkreviewMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 HammackDocument26 pages2009 HammackMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- T J L S: He Ournal of Abor and OcietyDocument7 pagesT J L S: He Ournal of Abor and OcietyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2010 KickedoutDocument3 pages2010 KickedoutMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 WritingDocument5 pages2009 WritingMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Housing Works, Shelter Kills!: Mayors, and - More Than Anything Else - BuiltDocument12 pagesHousing Works, Shelter Kills!: Mayors, and - More Than Anything Else - BuiltMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 ShukaitisDocument1 page2009 ShukaitisMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 FournarrativesDocument36 pages2009 FournarrativesMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2008 LiminalitiesDocument30 pages2008 LiminalitiesMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- On Challenging Authority: An Oral History Interview With Frances Fox PivenDocument13 pagesOn Challenging Authority: An Oral History Interview With Frances Fox PivenMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Defending Democracy, History, and Union Square (One Zap at A Time)Document5 pagesDefending Democracy, History, and Union Square (One Zap at A Time)Marc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- The Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives On Art, Politics and CultureDocument3 pagesThe Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives On Art, Politics and CultureMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2007 AidspolicyDocument32 pages2007 AidspolicyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2007 BridgingDocument18 pages2007 BridgingMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report: Tarlac Provincial JailDocument1 pageAccomplishment Report: Tarlac Provincial Jail잔돈No ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit of Daniel Paulo Re Sps Llames Vs Bebeng Dela CruzDocument3 pagesJudicial Affidavit of Daniel Paulo Re Sps Llames Vs Bebeng Dela CruzReginaldo BucuNo ratings yet

- Public Attorney'S Office Citizen'S Charter: MissionDocument10 pagesPublic Attorney'S Office Citizen'S Charter: MissionmharmeeNo ratings yet

- 15 County Clerk Judge Attorney Fraud Title 18 Crimes Generic For Ideas ONLYDocument8 pages15 County Clerk Judge Attorney Fraud Title 18 Crimes Generic For Ideas ONLYAriesWayNo ratings yet

- Raptors President Masai Ujiri's CounterclaimDocument108 pagesRaptors President Masai Ujiri's CounterclaimToronto StarNo ratings yet

- Memorial For The Petitioner - F-2Document24 pagesMemorial For The Petitioner - F-2Rajeev Sharma100% (1)

- DRCVDocument38 pagesDRCVthesacnewsNo ratings yet

- DBP Pool of Accredited Insurance Companies vs. RMN, 480 Scra 314, January 27Document15 pagesDBP Pool of Accredited Insurance Companies vs. RMN, 480 Scra 314, January 27Dennis VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Nuisance Abatement Settlement AgreementDocument13 pagesNuisance Abatement Settlement AgreementHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- SC Circular Am No 05-11-04 - SCDocument20 pagesSC Circular Am No 05-11-04 - SCColleen Rose GuanteroNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 486, Docket 32662Document3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 486, Docket 32662Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Marxism in The StrangerDocument9 pagesMarxism in The Strangernikpreet45No ratings yet

- 1 Tano vs. SocratesDocument9 pages1 Tano vs. SocratesdoraemoanNo ratings yet

- Tison Vs CADocument7 pagesTison Vs CAAlthea Angela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Frauds and Illegal Exactions and TransactionsDocument42 pagesFrauds and Illegal Exactions and TransactionsRaymond Alhambra100% (1)

- Manthan Jindal Refusal of Listing by A Stock Exchange - Judicial TrendDocument5 pagesManthan Jindal Refusal of Listing by A Stock Exchange - Judicial TrendNeelam TripathiNo ratings yet

- De Lima vs. Guerrero PDFDocument213 pagesDe Lima vs. Guerrero PDFanon_614984256No ratings yet

- Legal Profession OverviewDocument12 pagesLegal Profession OverviewLois DNo ratings yet

- Female Gang Membership - Current Trends and Future Directions - Police Chief MagazineDocument6 pagesFemale Gang Membership - Current Trends and Future Directions - Police Chief MagazineJacobNo ratings yet

- People V Kiichi OmineDocument2 pagesPeople V Kiichi Ominexynister designsNo ratings yet

- M. M. Lihn v. Civil Aeronautics Board, 272 F.2d 674, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document2 pagesM. M. Lihn v. Civil Aeronautics Board, 272 F.2d 674, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mizera v. Google - Document No. 32Document2 pagesMizera v. Google - Document No. 32Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Step-By-Step Guide To Subpoenas and Depositions in Immigration CourtDocument46 pagesStep-By-Step Guide To Subpoenas and Depositions in Immigration CourtUmesh HeendeniyaNo ratings yet

- Emma Poroger Sentencing MemoDocument85 pagesEmma Poroger Sentencing MemoStaten Island Advance/SILive.comNo ratings yet

- United States v. Maurice Trotter, A.K.A. Mo Mardell Trotter, A.K.A. Juice, A.K.A. Del, 483 F.3d 694, 10th Cir. (2007)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Maurice Trotter, A.K.A. Mo Mardell Trotter, A.K.A. Juice, A.K.A. Del, 483 F.3d 694, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ash DegDocument77 pagesAsh DegSammiFee78% (9)

- Remrev CasesDocument15 pagesRemrev CasesMV FadsNo ratings yet

- Jus CogensDocument8 pagesJus CogensMalvika SinghNo ratings yet

- Motion To Quash Practice CourtDocument7 pagesMotion To Quash Practice CourtSayeret MatkalNo ratings yet

- Zenith Insurance Vs CADocument2 pagesZenith Insurance Vs CANC BergoniaNo ratings yet