Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2010 Playand

Uploaded by

Marc Allen Herbst0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

549 views22 pagesQueer theory has long built on a defiant view of politics, gender, social categories and citizenship. The divide between social justice minded queers and assimationist gays has only grown wider. GLBT groups have sought to portray the gay community as "just like everyone else"

Original Description:

Original Title

2010_playand

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentQueer theory has long built on a defiant view of politics, gender, social categories and citizenship. The divide between social justice minded queers and assimationist gays has only grown wider. GLBT groups have sought to portray the gay community as "just like everyone else"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

549 views22 pages2010 Playand

Uploaded by

Marc Allen HerbstQueer theory has long built on a defiant view of politics, gender, social categories and citizenship. The divide between social justice minded queers and assimationist gays has only grown wider. GLBT groups have sought to portray the gay community as "just like everyone else"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 22

1

Shepard, B. (2010). Queer Politics and Anti-Capitalism: From Theory to Praxis. In S.

Burkhard. Queering Paradigms. (Pp.81-100) Berlin: Peter Lang Publishing Group.

"What queer theory has yet to learn," Douglas Crimp (2002) writes in the final lines of

Melancholia and Moralism, is "how...we make what we know knowable to the legions?" (p.

301). While, queers have always known pleasure as a resource, the challenge remains how to

articulate such a defense in a way which influences lived struggles, in the streets as well as the

seminar rooms. Queer activism has long demonstrated that there are countless ways of building

family and community outside of conventional patriarichal family structures (DEmilio, 1993;

Shepard, 2009). Queer theory has long built on a defiant view of politics, gender, social

categories and citizenship (Butler, 1990; Jargose, 1996). While queer theory was born of

reflection on activist struggle (Crimp, 2002; Hall, 2003, Jargose, 1996), over the years the fields

challenge has been to inject this broad and bountiful, often anti-capitalist disposition into real

world social and political struggles (Mattilda, undated).

Muddling this picture is another ongoing problem: divining and defining the very nature

of queer and gay lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) activism. In recent years, the divide

between social justice minded queers and assimationist gays has only grown wider. On one side,

stand queers who link the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) movements with

broader social justice issues. On the other side, stands a bureaucratic cadre of single issue gay

assimilationist organizations who aspire to a place at the policy table. Queers, who envision their

movement as a critique of social, sexual, and economic social norms, have long called for

something bigger, richer, and more profound than just fitting in. However, GLBT groups have

sought to portray the gay community as "just like everyone else", turning their back on issues

2

such as AIDS, homelessness, gender self determination and immigration in favor of law and

order social policies, access to marriage, and military service (Crimp, 2002; Warner, 1993). As

an assimilationist gay political movement has grown, so has this conflict. Ultimately, queer

theory has found itself staring down charges of obsolescence.

One way to approach such a challenge is by thinking about the concept of praxis, in

which theory and practice intersect. Here, theory is considered as the application of knowledge

to action. It is one thing to study and analyze the world, yet the important task involves

application, so theory is used to actually improve the conditions of peoples lives. The challenge

is to establish a framework for an interplay between knowledge and action, theory and practice

(Marx and Engels, 1976; Schram, 2002). Without this, the gap between theory and action

widens. For queer theory, the challenge involves how to link its critique with a route toward

action, a feedback loop for reflection, and synthesis connecting these understandings. Without

such a praxis, queer theory will continue stray from the action which once propelled the field.

The following considers both the efforts to describe a queer disposition as well as

struggles between academic and activist understandings of this worldview. It includes a short

overview on the history of this position as well as case examples of activist struggles which

reflect both the tensions and possibilities of the application of the theory and practice to politics.

Case examplars involve disputes over differing forms of public space including reproductive

rights, sexual freedoms, access to constitutionally protected services, community gardens, urban

space, and freedom of assembly. After all, if queer theory is to be taken seriously, then it has be

linked with acts of "queer" politics.

Queer Theories

3

Throughout the early 1970s, writers borrowed from traditions, from Marxism to

psychoanalysis, feminism to post modernism, to articulate the broad message of gay liberation.

Gay papers, born as underground press, focused on urban life, activism, politics, to cover the

movement. As the AIDS crisis hit outsiders everywhere, they helped transform an analysis of

AIDS activism into a theory of action. And activists and scholars established the groundwork for

a broad critical framework eventually recognized as queer theory.

Three proponents of this framework were Douglas Crimp, Michael Warner, and Eve

Kosofsky Sedgwick. Crimp (2002) helped inject a scholarly analysis into ACT UP's challenge

to the phobic representations of the epidemic. He argued violence against queers whether

leveled at women on welfare, injection drug users, or men who have sex with men in public

functions out of a similar anti humanist ethos. Similarly, Sedgwick (1994) suggested that queer

no longer be linked exclusively with sexual identity. As the 1990s progressed, queer organizing

churned forward bending cultural identifies, gender roles, and expectations. Here, Warner

(1993) envisioned a new politics which rejected interest group representation, defining itself

against "the normal rather than the heterosexual (P. xxvi). Rather than calling for interest group

representation for gay people, queer theory dissected the ethics of democratic citizenship and

public life, especially when it came to the stigma of HIV and illness. Once involved in the fight

to end the AIDS crisis, queer identity would never again be the same (Crimp 2002). In linking

its struggle with those of struggles among other outsiders, queer activism crossed a Rubicon. As

a concept and taxonomy, queerness had come into its own, simultaneously challenging notions

of heteronormativity and grappling with a bountiful array of impulses and identities. Yet, not

everyone agreed with its assumptions.

4

The field suffered its share of growing pains as it has become an academic discourse

(Goldstein, 1997). [I]ts own blind spots, lapses, inconsistencies, and nervous avoidances must

be foregrounded if it is to avoid becoming yet another manifestation of the normalizing forces

that it claims to critique and to work to undermine Donald Hall (2003) argues (p.8). In addition

to the academy, a number of queer theorys positions have met stark opposition in the political

arena (Shepard, 2009). For example, many activists reject its vanguardism. The concept came

from activists and was appropriated by academics, not the other way around Hall (2003) notes

(p.80). If the field is unable to communicate its precepts beyond graduate school, then its

political relevance comes into question.

A recurring difficulty with current queer theory is this: it often lacks a connection with

the embodied practices which help contribute to a queer praxis. In this absence, activists have

come to accuse academic queer theorists of divorcing the theory from its activist roots. Activist

Mattilda aka Matt Bernstein Sycamore (2004) experienced this first hand during an academic

conference at the University of Michigan: organized under the theme, Gay Shame, a reference

to the San Francisco activist group of which she was a member. At the conference, Mattilda and

company realized theirs was the only panel on activism. [W]e were a fetish object called on for

a few realness points. So, Mattilda and company used the opportunity to, stimulate a debate

on this blatant appropriation. Mattilda opened the Gay Shame panel by explaining there was a

typo in the program. Rather than Gay Shame the program should have read, Gay Sham.

What she saw was that: academics appropriate anything that they can get their hands on

mostly peoples lived struggles, activism and identitiesand claim to have invented them

The aim of her intervention was to cultivate a dialog. Yet, this was not a conversation the

5

academics wanted to have. Instead, we were met with shouting and blatant attempts to

immediately silence us, Mattilda observed. The Gay Shame conference was not an isolated

incident. The divide between queer activism and theory was expanding.

Yet, there are ways to address the divide between theory and practice now facing queer

politics. One way to prevent the theoretical cul de sac Mattilda describes is to link a queer social

knowledge of politics, and activism within an activist recognition of the subversive possibilities

of pleasure. Queer activism has long involved defense of sexuality and difference; queer theory

can only benefit by reflecting and supporting, rather than obscuring such activist practices.

Queers have a long history of appropriating space with an eye towards repurposing it for

other uses, including supporting the creation of communities of pleasure. Such a view builds on

the truism that there has to be more to life than work and necessity; hence the imperative of play

explained Herbert Marcuse (1955). Through embodied forms of play, activism, and

worldmaking, queers aspire to goals beyond equality or cultural assimilation. Rather than

embrace a bland GLBT agenda of military service, hate crimes laws, and marriage, a queer

politics of play involves a more ambitious and subversive agenda, involving creativity, play, and

acts of freedom (Shepard, 2009; Takemeto 2003).

Over the years, the free activity which characterizes a queer politics of play would take

on many tropes. One recurring trope was anti-capitalism. Rather than articulate capitalism with a

somber approach, queer politics tend to reject the obligatory docile bodies and alienated social

relations which support it (Berman, 1999; Ollman, 1971). Rather than view procreation as

production, queer activism favors eros and pleasure as ends unto themselves (DEmilio, 1993).

Rather than view urban space as an engine for economic growth, queer politics embraces the use

of public space for social connection, democracy, community building (Mitchell, 2003). Finally,

6

rather than adhere to authoritarian police controls, play favors constitutionally guaranteed forms

of democratic expression and freedom of assembly. The cases to follow consider just this queer

approach to play and pleasure to help articulate a queer political praxis.

Case One Clinic Defence

"[Q]ueer, can afford an access to the jouissance that at once defines and negates us, Lee

Edelman (2007) writes (p.5). Given the subversive nature of queer play, many seek to restrict it.

While queer politics involves both a subversive view of pleasure and political participation, over

and over again, it has been forced to confront the specter of panic over its challenge to the

normative notions of family and citizenship in which alienation reasserts itself as primary social

relation. The process often begins with the image of the child as a trope. On every side, our

enjoyment of liberty is eclipsed by the lengthening shadow of a Child, writes Lee Edelman

(2007, p. 21). This child must grow up unfettered by contact with social outsiders, or even by

the threat of potential encounters, with an otherness of which its parents, its church, or the state

do not approve, uncompromised by any possible access to what is painted as alien desire

Edelman continues (p. 21). Activists have long fought to challenge this prohibitive, enclosing

logic.

On a rainy Saturday morning in November, 2008 a group of anti-abortion activists, led

by Bishop Bishop Caggiano, assembled to hold a prayer vigil outside of a women's health

facility in Sunset Park, a neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. But when the Bishop and his

group arrived, they were met by a coalition of pro-choice groups: the Rude Mechanical

Orchestra, the Brooklyn Pro Choice Network, and the Church Ladies for Choice and (of which

this writer is a member). These groups were dedicated to both ensuring access to clinics as well

as street theatre to convey their political agenda.

7

The Rude Mechanical Orchestra (RMO) and the Church Ladies each used songs as a

component of their street theatre. Dressed in green and black marching band uniforms, RMO

members performed Salt and Peppas Push It injecting the words Hands off Our Bodies into

the chorus to drive home their manifesto. The Church Ladies offered parodies of popular

traditional songs with gay and pro-choice lyrics. If You are Happy and You Know It was sung

to the words, If you are Pro Choice and You know It Kiss a Dyke. The Woody Guthrie

anthem This Land is My Land took on a pro-choice message with this reinterpretation:

This womb is my womb

It is not your womb

And there is no room for Bishop Caggiano

From Flushing Meadow on Down to Bay Ridge

These wombs were made to be free!

As I was walking up to a clinic,

I got socked by a psycho-Catholic

He showed me pictures and showed me lies

I said my womb belongs to me refrain (Church Ladies hymnal, P. 6).

Building on the folk tradition used to mobilize crowds for generations, the Church Ladies

perform Malvina Reynolds homage to suburban monoculture, Little Boxes, changing the

lyrics to Psycho Christians. The first verse highlights the dominant racial make-up of the anti-

choice movement.

Psycho-Christians, blocking health care

Thats the way they get to heaven

Psycho-Christians, blocking health care and they all look just the same

Theres a white one

And a white one

And a white one

Psycho-Christians, blocking health care and they all look just the same (Church Ladies

hymna, P. 4).

The second verse explicitly highlights the homophobia of anti-choice activists.

Psycho-Christians, taunting homos

Thats the way they buy indulgences

8

Psycho-Catholics, taunting homos

And they all look just the same

Theres a closet case

And a closet case

And a closet case

And a closet case

Psycho-Catholics, taunting homos

And they all look just the same (P. 4).

Even some police officers laughed at the Church Ladies brand of radical ridicule. The Rude

Mechanical Orchestras performance climaxed with a rendition of the 1980s heavy metal

anthem 'We're Not Going to Take It' as the anti-choice contingent, still praying, departed the

scene.

Of course, this cultural activism campy not a new approach. US anarchist Emma

Goldman brought the same ingredients to her early-Twentieth-century struggle for reproductive

freedoms. In February 1916, Goldman was arrested while speaking about abortion, in violation

of the Comstock Law. After her arrest she explained that the battle over birth control had

become: a war of the oppressed and the disinherited of the earth against their enemies,

capitalism and the state, a war for a seat at the table of life, a war for well being, for beauty, for

liberty (Zinn, 2004, p. 34). She concluded, Above all this war is for a free motherhood and a

joyous, playful, glorious childhood.

For Goldman, whose work helped establish the foundations for both anarcha feminism

and queer theory, an anti-capitalist critique overlapped with the pursuit of a richer experience of

the world on ones own terms. Much of Goldmans philosophy was based on a broad belief in

personal freedom. For Goldman, joy and justice intermingled, neither able to exist without the

other. Today, Goldmans adage on dance and revolution provides the underpinnings for the street

party-style protest of Reclaim the Streets and the global justice movement of movements.

9

Her thinking reflects a distinct humanist approach to queer politics. Writing about this

world view Lee Edelman suggests this kind of politics: delights in the morality as the negation

of everything that would define itself, moralistically, as pro-life, (p. 31). Of course, advocates

such as the Singing Nun, Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman sacrificed everything to

challenge the pseudo morality of the Comstock law which linked discussion of reproductive

health with obscenity (Gilfoyle, 1992; Kendrick, 1996).

Over the next century, queer activists would continue to battle the prohibitive politics of

Comstocks ilk. Taking apart the arguments of the self appointed moralists, would remain an

ongoing target of queer politics and activism. Current battles over abstinence-only sex education

mirror much of this the struggle between supporters of sexual self determination and advocates

of social control dating back to the Comstock era (Gilfoyle, 1992; Kendrick, 1996). Within this

context, a queer imperative still resonates. The point of queer theory and activism, of course, is

that abstinence is an unworkable approach, borne out by rising HIV transmissions. Sexual

repression is unhealthy.

Much of this debate has yet to be resolved. The struggles between personal autonomy

and social control which mark the clinic stand-offs, are emblems of a larger contested space.

[Q]ueerness names the side of those not fighting for the children, the side outside consensus,

Lee Edelman (2008) suggests (P. 3). [Q]ueerness, by contrast, figures, outside and beyond its

political symptoms, a place, to be sure, of abjection expressed in the stigmaa place from

which liberal politics strives quite reasonably, given its unlimited faith in reason to dissociate

the queer, (p. 3). The second case example explores just such a circumstance.

Case Number Two Urban Spaces

10

The history of queer activism is marked by efforts to break apart silences which support

social inequalities. Queer organizing finds its roots in the 1966 disruptions at the Black Cat Bar

in Los Angeles and Comptons Cafeteria in San Francisco, as well as the 1969 riots at The

Stonewall Inn in New York. These watershed moments were followed by subsequent challenges

to sodomy laws, psychiatric classifications, and public mores around pleasure. By the 1970s, the

Gay Liberation Movement was dynamic and vast. Throughout the decade the movement linked

its work with a struggle to create a queer public commons, including bath houses, piers, and

other public spaces. Here queers recognized that a democratic pursuit of happiness included

countless permutations, many taking shape in spaces where outsiders and members of the tribe

converged, including bath houses, hussler bars, clubs and community gardens (Benderson, 2007;

Crimp, 2002).

Throughout 1990s, queer activists helped defend public spaces from the encroaching

developers from suburbia. Veterans of ACT UP joined environmental activists to save green

spaces, having been reclaimed from vacant lots and built up into verdant oases (Mitchell, 2003).

Gardens functioned as particularly subversive spaces where a cross section of neighbors from all

walks of life converged to share space and build common ground; these spaces cultivated

alternative models for social relations which could thrive outside the parameters of buying and

selling, and other workings of capitalism (Holtzman et al, 2007). This, of course, is part of why

they were under attack.

Queers have long participated within such campaigns and politics. Recall the genderfuck

queer performance group, the Cockettes, from the early 1970s. Members of the group first

performed unclothed in the trees in San Franciscos Golden Gate Park. When the Palace, where

the group found a space for their shows, started charging entrance fees for their shows, their

11

founder Hibiscus revolted. Ever an advocate of play over professionalism, Habiscus opened the

back door of the Palace, so fans without money could attend (Tent, 2004). Play has to be free.

Yet, the issue of public vs private spaces never resolved itself vis a vis queer activism. More

than anything, queer conjures the poetic contradictions of politics and social life. Queer marks

the other side of politics, Lee Edelman (2007) suggests (p.5). (p.7).

None of this is to suggest this makes such politics simple. Throughout the Spring of

1999, the City of New York planned to auction off hundreds of community gardens. I had been

participating in civil liberties activism as a member of both the Lower East Side Collective

(LESC) and SexPanic!, two groups fighting the restrictions of the Quality of Life Crusade. One

of my first actions with LESC was participating in a direct action campaign to successfully halt

the sale of 114 community gardens earlier that spring. Activists had been less successful in

defending public sexual spaces. So that June 1999, SexPanic! planned to hold a community

forum on the loss of public sexual spaces. I was interested in building the linkages between

groups facing attacks on their meeting spaces from the West Side of the City to the East Side of

the city. What connected these spaces was their importance as meetings spaces. While members

of LESC were veterans of queer activism, others in the garden movement were reticent about

considering the linkages between movements and various struggles for public space. June 16

th

,

1999 I posted a notice on a SexPanic! event dubbed, Vanishing Queer New York to be held at

the Lesbian and Gay Community Center on a garden listserve called Cyberpark.

-> Hear about New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani's war on Queer New York --

-> The Latest Targets

-> Attacks on Sexual Civil Liberties

-> Disruption of HIV Prevention Efforts

-> Please join us for this crucial community discussion and

-> Help us make plans for resistance

12

-> XXX Shops -- ZONED OUT

-> Bathhouses -- PADLOCKED

-> Peep Shows -- OUTLAWED

-> The Piers -- POLICED

-> Bars and Clubs -- RAIDED

-> Cruisers in Parks -- BUSTED

Over the next week, activists debated whether I should have posted the announcement to the list.

Under the subject heading, Vanishing Queer New York, the flame war served to illustrate Lee

Edelmans point that queer marks the other side of politics. Differing views of public space,

approaches to civil liberties, and sexual civil liberties found expression through the week long

discussion. On the one side, a moderator maintained a liberal view of public space and politics

which precluded debate about sexual liberties activism or public sexual culture; on the other side,

a wide range of activists suggested such discussions were entirely germane to debate over public

spaces such as gardens.

June 17

th

, 1999, I received a notice from list serve moderator informing me: In the

cyberpark listserv, discussion is limited to issues relating to parks and public space in the city of

new york. we have to make tough choices as to whether the posting is appropriate to THIS

listserv. The note concluded: While the issue you have brought to cyberpark is of great

importance, it is not appropriate to the discussion of public space.

The following day, I posted a public response to the entire list, defending my position

that my post on queer space was germane to a list serve dedicated to issues of public space.

Throughout the day, members of the list serve chimed in under the subject line, Re:

CYBERPARK: vanishing queer new york 86'd. The flame war of hostile interactions among

subscribers to the internet discussion list would last for the next week. One observer, Tim who

had gone to a few SexPanic! meetings addressed the list moderator, posting: I don't know who

13

made you king in deciding what is appropriate in issues around public space, gardens, parks, and

the individuals who use the spaces, plus the individuals that attack those places. Instead, he

suggested such issues overlap. Whether it is the plant, the earth, or the individual, I believe it is

appropriate for any issue to be on this listserve for all persons interested in the remaining public

spaces of New York. Tim concluded his post with a call for tolerance and connection. Other

posts were informed by a distinct theoretical understanding of the queer meanings of public

space. A small group of gay activists chimed in about the connections between cruising and

public space. On June 20

th

, Mark wrote:

As far as I can tell, all Ben did was post a notice about a Sex Panic! event

that concerned many of the sorts of spaces under discussion on this

list--piers, parks, public streets. Even the quickest examination of queer

culture shows the importance of these spaces Yeah, queer public space is about getting

off (which is a reasonable end in itself), but also about finding and making community,

HIV education, political outreach, creating art, and a whole lot more.

More than anything, the author suggested that a queer perspective involved grappling with

notions of difference. One of the reasons for coming to a public space, even a virtual public

space such as CyberPark, is to encounter the unfamiliar and perhaps unsettling.

It's about exploring difference. Given most of the participants on the cyberpark list preferred

the gritty, crowded New York street to the whitebread mall, a wiser course of action is to

initiate discussion, rather than stifle conversation. [L]iving in NYC is all about experiencing

the unexpected, the different, starting dialogues with all sorts of diverse peoples, which is what

the Giuliani administration seems intent on subduing.

While the recognition that people are different is a core axiom of queer theory (Hall,

2003), the principal is easier in theory than in application, especially in relation to questions

about sexuality and public space. Marc recalled a similar flame war which took place when he

posted a call for a Gays for Gardens contingent at the Pride parade the previous year. While it

14

is not always comfortable, the public commons can generally handle the specter of difference.

Yet an appreciation for the democratic nature of public space informs such a position. The point

of queer activism continues to be to push such ideas into the light of day, queering paradigms of

self, community and public space.

[L]et's get down to brass tacks, Mark continued. Many of the strategies used in the

recent victorious campaign to save the auctioned gardens were derived from groups like Act Up,

Lesbian Avengers, and the queer-infused Livermore Action Group. Such activism helped

transform the movement, infusing it with a raw burst of activist knowledge and practice.

Linking queer activism with the struggle for community gardens, the post helped connect

the dots attacks on queers with the concepts of self determination and public space. A good

friend of mine was held in jail overnight simply for using a Central Park bathroom in the middle

of the afternoon and looking queer, Mark continued, noting that to a certain degree he had been

censoring himself. I realize that these are difficult, touchy subjects to bring up. (That's why Sex

Panic! is such a great name for a group.) Yet, he called for members of the list to encourage,

rather than discourage, their involvement. We've all had too much shame in our life already. In

many ways, the debate over the queering of public spaces took a liberal leaning discussion list

and turned it into a space for debate over difference. By the time it was over, the covert silences

over homophobic discourse felt disrupted.

Well, you managed to stir things up quite a bit! Good for you. I think skirmishes like

this are very good, Bob Kohler, a Stonewall veteran, who was also involved with SexPanic!

would write me when I sent him some of email thread that Sunday the 20

th

of June. Later in the

day, CIRCUS AMOK, a New York queer performance group, planned to put on a free show in

Tompkins Square Park with a free, fabulous, with a community garden theme! one Cyberpark

15

member would noted, advertising it on the list, reconfirming the links between queer space and

public space. By the end of the week, the topics of harassment of cruisers, public sexual culture,

and stigma had become a part of the debate about the gardens, along side debates about civil

disobedience, green space and DIY politics. Linkages between identities and activist

communities are never simple. Yet, as the case suggests, a theoretically informed queer activist

perspective can help queer paradigms and conceptions of meaning of public space.

Case Number Three Parade Without a Permit

Spring of 2007, both veterans and first time activists discussed plans for the twentieth

anniversary of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). As the group outlined plans for

its anniversary action, a number of age old debates over conflicts between identity based GLBT

and a more post modern queer understanding played themselves out over the ACT UP 20 List

serve. ACT UP is historically credited with infusing a critical praxis into queer theory and vice

versa (Crimp, 2002). So it was not surprising these debates took hold during discussions of its

anniversary action. At issue was the very nature of queer activism. April 12, 2007, I posted a

call for a parade without a permit organized by a new queer direct action group called the

Radical Homosexual Agenda (RHA).

PARADE WITHOUT A PERMIT!***

An Un-Permitted Queer Parade to Call Out Christine Quinn and Defend Free

Assembly

Calling All Queers, Allies and Anyone Effected by NYPDs New Rule (AKA

Everyone in NYC)!! Join us in the streets as we challenge the NYPDs new

law preventing assembly. Or cheer us on from the sidelines.

Early in 2007, the NYPD published new regulations restricting freedom of assembly in New

York City. Working with the speaker of the City Council, who happened to be a lesbian, the

16

police altered the definition of a "parade." Any public gathering of 50 or more people would

require a "permit" from the NYPD. The last line included a nod to history. The Stonewall

veterans never asked for a permit and neither should we!

Shorter after I posted the Parade without a Permit announcement, one of the founders

of ACT UP posted a comment on my post under the subject line, Re: [actuparmy] unpermitted

parade declaring: Here is a fine example of queer activism - :-) I like it - Eric Sawyer Over

the next year, the Radical Homosexual Agenda would build on the coalition of gardeners, bikers,

queer activists and public spade advocates who took part on the gardens direct action of the

previous decade to help frame issues of freedom of assembly as a queer issue. Members of RHA

would fight the permit regulations and for the right of freedom of assembly, at every turn,

participating in a number of unpermited parades, yearly drag marches, and critical mass bike

rides, reminding organizers that issues of freedom of assembly are essential to a queer organizing

ethos. Without public space, it is very difficult to think about issues of democracy, members of

the group would insist.

Throughout the next two years, members of RHA would fight the permit regulations and

for the right of freedom of assembly, at every turn, reminding organizers that issues of freedom

of assembly are essential to a queer organizing ethos. Without public space, it is very difficult to

think about issues of democracy, members of the group would insist. The RHAs queer

perspective on movement history helped infuse a vitality into the activism and debate over the

permit laws.

Summer 2008, members of RHA met with the Radical Faeries, the Church Ladies and

many others for the annual Drag March, held the Friday of Pride weekend. An unpermitted

action, a march from Thompkins Square Park, on the East Side of the City, to Stonewall Inn, on

17

the West Side, the boisterous yearly event was just the kind of issue RHA was defending when it

organized against the parade permit rules. While the 2008 parade turned out to be a joyous,

playful spectacle, it was just about shut down before it could begin.

Hucklefaery, who helped organize the event, wrote about hitting the streets with the other

organizers, including the Church Ladies and Radical Faeries, to elude the police through a cat

and mouse game of direct action. At first, he confessed that he panicked when the police

approached.

Who's in charge they asked.

No one, Hucklefaery stammerred, bluffing for time.

Do you have a permit? they asked.

I don't know? he bluffed.

You're all going to jail, the cop retorted.

While this conversation was taking place, the Church Ladies clogged the street with drag

queens, friends, and supporters in various stages of drag and undress. Songs and chants echoed

through the Village air as the sun started to set. After speaking with police, Hucklefaery turned

around to see the street clogged with queer bodies. [W]hen you guys held the street, it was so

fucking inspiring that I went back to the cops and made them listen... Emboldened he told

around and informed the police, "No we're not getting arrested... where were you - we've been

waiting for you, what the hells going on... you've shown up for fifteen years...? Can't you talk to

someone and fix this? They were dumbfounded... Hucklefaery would confess. I haven't truly

figured out who I was channeling... Yet, there was a method. [I]t was pleading, but also a bit

bossy and... compliant as long as you did what I asked... I guess that makes me a power

bottom... Bottoms rule.

18

Looking around the police saw hundreds and hundreds of drag queens dressed to the

nines filling the streets on a weekend celebrating a riot. And, the police gave in. [T]hey asked

were we wanted to go and said they'd get us to Broadway - then we'd have to deal with another

precinct ... who also came around to get us to stonewall. I felt like a pro, Hucklefaery noted. I

really think those first cops were just so overwhelmed at they didn't know what to do... but they

warmed quickly, he explained. [T]hey were even encouraging... do what you gotta do, they

told me when they handed us off to the other cops... By this point, Hucklefaery was bantering

with many of the police. I felt like they had joined us... the second group was a little more

ridged, but their community outreach people showed up at Stonewall and apologized profusely.

They police explained they had had a group at Tompkins earlier ready to escort the drag march,

but didn't wait long enough and left. I told them we were drag queens and were always

late. They said they loved doing it and they were all really bummed to have missed it.

Hucklefaery thanked the Church Ladies for helping infuse the action with cornerstones of

queer political performance and protest. These elements included: challenging fear, standing

up and standing strong, and, for lifting me up to new heights of realization and ACTION!

Here, Hucklefaery alludes to a tradition of queer activism informed by principles of direct action,

yet aimed highlighting a specter of difference. I think it's a strength that we raise different

energies in different ways and by different means, Hucklefaery insisted, but by making room

for both all and more, by making room for difference, we are so encompassing, we just swallow

ya up... we are a vast and varied lot ...

Most importantly, queer direct action is informed by a bountiful energy of play. I loved

killing the cops with kindness, while you told 'em to fuck off, Hucklefaery noted, in a nod to the

disarming paradoxical effort. [I]t is where the colors clash that they truly accentuate each

19

others' strengths and uniqueness... But it is by coming together we create promise... The ludic

quality of the march opened up any number of liminal spaces for activism, pleasure, and blurred

identity. The note ended with a confession: It was my favorite Drag March Ever!

Conclusions

Actions speak louder than words. This not a new saying. Yet, this old activist expression

speaks to the divide between the theory and application of a queer approach to living. Through

the intersection between theory and case exemplars, the essay aims to bridge the gap between

abstract theory and activist practice. Each action a battle over reproductive rights/autonomy of

the body, a discursive battle over the meanings of public space and democratic political

participation, and struggles for freedom of assembly and by extension civil liberties highlights

a theoretically and historically informed approach to queer activism. Each is informed by a

subversive aim to describe, defend, and substantiate a queer world making project. In the first

case, we see a defense of non-procreative (code non-productive) sexuality; the second, a

discursive debate over public spaces; and the third, a debate over public assembly followed by

the ludic defense of public space. Throughout the case examples, a queer approach to activism is

linked with a theoretical rejection of prohibitive politics which informs queer theory. To stay

vital, such theory and action must be able to play, intermingle, and feel embodied. Each case

example is informed by a distinctly anti-capitalist framework for social relations. This is part of

why opposition remains formidable. Such rebellion against repressive policies is anything but

20

simple to achieve, yet we see each taking a shape through their interplay between theory and

action. For it to remain vital, queer theory and activism must continue to be informed by a

boisterous praxis. Such theoretically informed action is most effective when linking its analysis

with a bigger, brighter approach to queer community building. More than analyze, such a theory

must inform struggles to create change. Herein queers link an identity bending universalizing

discourse, which embraces outsider status, with a struggle for a richer more expansive

democratizing experience of self, community, and citizenship.

References

The author would like to thank Jay Blotcher for his edits and friendship.

Benderston, Bruce. 2007. Sex and Isolation. Madison, Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin Press.

Berman, Marshall. 1999. Adventures in Marxism. New York: Verso.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble. London: Routledge.

Church Ladies Song Book. Undated. http://www.churchladies.org/ Accessed 1 December, 2005.

Crimp, Douglas. 2002. Melancholia and Moralism. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

D'Emilio, John. 1993. Capitalism and Gay Identity in The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader ed.

by Henry Abelove, Michele Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin. New York: Routledge.

Gilfoyle, Timothy. 1992. City of Eros: New York City. New York: WW Norton.

Goldstein, Richard. 1997. Its Here, Its Queer! Its Too Hot for Yale. Village Voice, (29 July): 38

-40.

Hall, Donald. 2003. Queer Theories Palgrave Macmillan. New York

Holtzman, Benjamin; Hughes, Craig; and Van Meter, Kevin. 2007. Do It Yourself.... Radical

Society. 29 (1) (2002 April) 7-20

Jargose, Annamarie. 1996. Queer Theory. New York: New York University Press.

21

Kendrick, Walter. 1996. The Secret Museum. University of California Press.

Marcuse, Herbert. 1955. Eros and Civilization New York: A Vintage Book.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Friedrich. 1976. Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

International Publishers.

Mattilda aka Matt Bernstein Sycamore. 2004. Gay Shame. Accessed 20 December, 2008 from

http://www.gayshamesf.org/slingshotgayshame.html

Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City. New York: Guilford Press.

Ollman, Bertell. 1971. Alienation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schram, Sanford. 2002. Praxis for the Poor. New York: NY

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 1994. Tendencies. New York: Routledge.

Shepard, B. (2009) Queer Political Performance and Protest: Play, Pleasure, and

Social Movement. New York: Routledge.

Takemoto, Tina. 2003. Interview with Douglas Crimp. Art Journal.Winter.

Tent, Pam. 2004. Midnight at the Palace. Los Angeles: Alyson Books.

Warner, Michael. 1993. Introduction, Fear of a Queer Planet. Edited by M. Warner.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Zinn, Howard. 2004. The People Speak. New York: Harper Collins.

22

You might also like

- Hannah McCann and Whitney Monaghan - Queer Theory Now - From Foundations To Futures-Macmillan International - Red Globe Press (2020)Document21 pagesHannah McCann and Whitney Monaghan - Queer Theory Now - From Foundations To Futures-Macmillan International - Red Globe Press (2020)João SantosNo ratings yet

- How Kinship Systems Change: On the Dialectics of Practice and ClassificationFrom EverandHow Kinship Systems Change: On the Dialectics of Practice and ClassificationNo ratings yet

- Abu-Lughod, Writing Against CultureDocument14 pagesAbu-Lughod, Writing Against CultureCarlos Eduardo Olaya Diaz100% (1)

- Clifford Geertz - Intellectual BiographyDocument15 pagesClifford Geertz - Intellectual BiographyLuis Zaldivar SchraderNo ratings yet

- Life and Words: Violence and The Descent Into The Ordinary (Veena Das)Document5 pagesLife and Words: Violence and The Descent Into The Ordinary (Veena Das)Deep Kisor Datta-RayNo ratings yet

- Strathern Out of ContextDocument32 pagesStrathern Out of ContextThiago FalcãoNo ratings yet

- Cunha, Olivia Gomes-Travel-Ethnography and Nation PDFDocument39 pagesCunha, Olivia Gomes-Travel-Ethnography and Nation PDFFlavio SantiagoNo ratings yet

- De La Cadena and StarnDocument17 pagesDe La Cadena and StarnJoeNo ratings yet

- Borreca 1993 - Political DramaturgyDocument25 pagesBorreca 1993 - Political Dramaturgybodoque76No ratings yet

- Nash, Catherine - Trans Geographies, Embodiment and ExperienceDocument18 pagesNash, Catherine - Trans Geographies, Embodiment and ExperienceCaitlinNo ratings yet

- Joanna Overing - Catch 22Document22 pagesJoanna Overing - Catch 22Diego MadiasNo ratings yet

- Beyond Abyssal Thinking Santos enDocument33 pagesBeyond Abyssal Thinking Santos envikky20045No ratings yet

- Deborah Bird Rose Slowly - Writing Into The AnthropoceneDocument7 pagesDeborah Bird Rose Slowly - Writing Into The AnthropoceneraquelNo ratings yet

- Social Suffering, Subjectivity, and The Remaking Ofhuman Experience - KleinmanDocument22 pagesSocial Suffering, Subjectivity, and The Remaking Ofhuman Experience - KleinmanMichelli De Souza RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Turkle Sherry What Does Simulation Want PDFDocument11 pagesTurkle Sherry What Does Simulation Want PDFmonterojuNo ratings yet

- Notes Epistemologies of The SouthDocument7 pagesNotes Epistemologies of The SouthNinniKarjalainenNo ratings yet

- Patrice Manglier: The Others' TruthsDocument1 pagePatrice Manglier: The Others' TruthsSimon BarberNo ratings yet

- Sharon W. Tiffany - Paradigm of Power: Feminist Reflexion On The Anthropology of Women Pacific Island SocietiesDocument37 pagesSharon W. Tiffany - Paradigm of Power: Feminist Reflexion On The Anthropology of Women Pacific Island SocietiesТатьяна Керим-ЗадеNo ratings yet

- Ethnicity. Problem and Focus in AnthropologyDocument26 pagesEthnicity. Problem and Focus in AnthropologyPomeenríquezNo ratings yet

- Ingold Temporality of The LandscapeDocument23 pagesIngold Temporality of The LandscapeMayara BragaNo ratings yet

- Evan Evans-Pritchard 1902 - 1973Document16 pagesEvan Evans-Pritchard 1902 - 1973Rodrigo ToniolNo ratings yet

- Bruno Latour - Two Writers Facing One Turing TestDocument17 pagesBruno Latour - Two Writers Facing One Turing TestfsprengerNo ratings yet

- Donzelot Anti SociologyDocument28 pagesDonzelot Anti SociologyEliran Bar-El100% (2)

- Determinants of PersonalityDocument2 pagesDeterminants of Personalityjmcverzola1004No ratings yet

- Sahlins Marshall. 1999. Two or Three Things That I Know About CultureDocument17 pagesSahlins Marshall. 1999. Two or Three Things That I Know About CultureValeria SeguiNo ratings yet

- Taussig, Mimesis and AlterityDocument2 pagesTaussig, Mimesis and Alteritynatural3000No ratings yet

- Barnard - Rules and Prohibitions 1Document30 pagesBarnard - Rules and Prohibitions 1Ilze LukstiņaNo ratings yet

- Kulick Masochist AnthropologyDocument20 pagesKulick Masochist AnthropologyTemirbek BolotNo ratings yet

- Okin Pateman CCDocument29 pagesOkin Pateman CCanthroplogyNo ratings yet

- Review - The Method of HopeDocument3 pagesReview - The Method of HopeMaria Cristina IbarraNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Wolf - Closed Corporate Peasant Communities in Mesoamerica and Central JavaDocument18 pages2.2 Wolf - Closed Corporate Peasant Communities in Mesoamerica and Central JavaREPTILSKA8100% (1)

- Toward A Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and PraxisDocument27 pagesToward A Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and PraxisSarah De100% (1)

- Sidney W. Mintz - Worker in The Cane - A Puerto Rican Life History-W W Norton & Co Inc (1974) PDFDocument161 pagesSidney W. Mintz - Worker in The Cane - A Puerto Rican Life History-W W Norton & Co Inc (1974) PDFRenata MilanêsNo ratings yet

- GREGORY, C. A. (1994) - Exchange and ReciprocityDocument29 pagesGREGORY, C. A. (1994) - Exchange and ReciprocityamaliaNo ratings yet

- Citizenship and Home - Political Allegiance and Its BackgroundDocument19 pagesCitizenship and Home - Political Allegiance and Its BackgroundRogers Tabe OrockNo ratings yet

- Edward W. Said - Identity, Authority, and Freedom - The Potentate and The TravelerDocument19 pagesEdward W. Said - Identity, Authority, and Freedom - The Potentate and The TravelerYoshiki SakumotoNo ratings yet

- Stocking 1968Document7 pagesStocking 1968Anth5334100% (1)

- Knowledge and WorkDocument26 pagesKnowledge and WorkOana Andreea Scanghel100% (1)

- Cosmologies in The MakingDocument112 pagesCosmologies in The MakingDouglas Ferreira Gadelha CampeloNo ratings yet

- Eriksen T. 1996. The Epistemological Status of The Concept of Ethnicity.Document11 pagesEriksen T. 1996. The Epistemological Status of The Concept of Ethnicity.jachenriquezNo ratings yet

- Pritchard - Social ANthropology - Past and PresentDocument8 pagesPritchard - Social ANthropology - Past and PresentArif Rahman BramantyaNo ratings yet

- Strathern, M. The Decomposition of An EventDocument12 pagesStrathern, M. The Decomposition of An EventBarbara RossinNo ratings yet

- Lemba 1650 1930 A Drum of Affliction inDocument50 pagesLemba 1650 1930 A Drum of Affliction inCaçador de HistóriasNo ratings yet

- Class 3 - Anthropology of The Body - 2020 - DouglasDocument16 pagesClass 3 - Anthropology of The Body - 2020 - Douglassite usageNo ratings yet

- CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M e ALMEIDA, M. Indigenous People, Traditional People and Conservation in The AmazonDocument25 pagesCARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M e ALMEIDA, M. Indigenous People, Traditional People and Conservation in The AmazonLuísa GirardiNo ratings yet

- 126-131 Sadiya Nair SDocument6 pages126-131 Sadiya Nair SEhsanNo ratings yet

- Book Forum - Lisa Stevenson's "Life Beside Itself"Document18 pagesBook Forum - Lisa Stevenson's "Life Beside Itself"admin1666100% (2)

- Alcida Rita Ramos - The Politics of Perspectivism PDFDocument18 pagesAlcida Rita Ramos - The Politics of Perspectivism PDFGabrielYgwyratinguiNo ratings yet

- Rachels' Basic Argument For VegetarianismDocument5 pagesRachels' Basic Argument For VegetarianismrichardcraibNo ratings yet

- 1.9999 - Serequeberhan, Tsenay - Karl Marx and African Emancipatory Thought. A Critique of Marx's Euro-Centric Metaphysics (En)Document22 pages1.9999 - Serequeberhan, Tsenay - Karl Marx and African Emancipatory Thought. A Critique of Marx's Euro-Centric Metaphysics (En)Johann Vessant RoigNo ratings yet

- Wolf (1970) - Anthropology On The Warpath in ThailandDocument20 pagesWolf (1970) - Anthropology On The Warpath in ThailandklderaNo ratings yet

- Bio Politics of Gendered Violence in Sahadat Hasan Manto's Stories, "Sharifan", "Xuda Ki Kasam" and "Ghate Ka Sauda": Reflections On Authentic Testimonies of TraumaDocument6 pagesBio Politics of Gendered Violence in Sahadat Hasan Manto's Stories, "Sharifan", "Xuda Ki Kasam" and "Ghate Ka Sauda": Reflections On Authentic Testimonies of TraumaIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Jeff Shantz - Green Syndicalism: An Alternative Red-Green VisionDocument10 pagesJeff Shantz - Green Syndicalism: An Alternative Red-Green VisionmelbournewobbliesNo ratings yet

- Diane Lewis - Anthropology and ColonialismDocument23 pagesDiane Lewis - Anthropology and ColonialismDiego MarquesNo ratings yet

- Trivers 1972Document48 pagesTrivers 1972juachhNo ratings yet

- Passmore - 100 Years PhilosophyDocument14 pagesPassmore - 100 Years Philosophyalfonsougarte0% (2)

- ROBBINS, Joel. Continuity Thinking and The Problem of Christian CultureDocument35 pagesROBBINS, Joel. Continuity Thinking and The Problem of Christian CultureLeo VieiraNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diamond in 3DDocument43 pagesCultural Diamond in 3DArely MedinaNo ratings yet

- Reflections Reflections: Narrative IN Social: Turn WorkDocument3 pagesReflections Reflections: Narrative IN Social: Turn WorkMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2011 SillyDocument4 pages2011 SillyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- FIELD 01 Herbst CulturalPolicyOfFailedStateDocument16 pagesFIELD 01 Herbst CulturalPolicyOfFailedStateMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Responding To Harvey: It's All About Organizing: Benjamin ShepardDocument11 pagesResponding To Harvey: It's All About Organizing: Benjamin ShepardMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Lambda Literary: Harvey Milk & The Politics of Neighborhood LifeDocument7 pagesLambda Literary: Harvey Milk & The Politics of Neighborhood LifeMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2010 RofesDocument33 pages2010 RofesMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Teaching Community Projects: Benjamin Shepard, Ph.D. New York College of Technology/City University of New YorkDocument7 pagesTeaching Community Projects: Benjamin Shepard, Ph.D. New York College of Technology/City University of New YorkMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Defending Democracy, History, and Union Square (One Zap at A Time)Document5 pagesDefending Democracy, History, and Union Square (One Zap at A Time)Marc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Anthony Fontana-Modesto Is A Freelance Journalist Who Writes On Leftist andDocument5 pagesAnthony Fontana-Modesto Is A Freelance Journalist Who Writes On Leftist andMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Housing Works, Shelter Kills!: Mayors, and - More Than Anything Else - BuiltDocument12 pagesHousing Works, Shelter Kills!: Mayors, and - More Than Anything Else - BuiltMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- The Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives On Art, Politics and CultureDocument3 pagesThe Brooklyn Rail: Critical Perspectives On Art, Politics and CultureMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2009 HammackDocument26 pages2009 HammackMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- T J L S: He Ournal of Abor and OcietyDocument7 pagesT J L S: He Ournal of Abor and OcietyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- On Challenging Authority: An Oral History Interview With Frances Fox PivenDocument13 pagesOn Challenging Authority: An Oral History Interview With Frances Fox PivenMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Electoral Guerilla Theatre: Radical Ridicule and Social Movements. L. M. Bogad. NewDocument3 pagesElectoral Guerilla Theatre: Radical Ridicule and Social Movements. L. M. Bogad. NewMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2007 PlayactivismDocument5 pages2007 PlayactivismMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2007 ReviewduncombeDocument7 pages2007 ReviewduncombeMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2007 AidspolicyDocument32 pages2007 AidspolicyMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- Toward A Ludic Counterpublic:: Benjamin ShepardDocument19 pagesToward A Ludic Counterpublic:: Benjamin ShepardMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2006 NotquiteDocument14 pages2006 NotquiteMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- 2006 RitalinDocument4 pages2006 RitalinMarc Allen HerbstNo ratings yet

- The Escalating Cost of Ransomware Hubert YoshidaDocument3 pagesThe Escalating Cost of Ransomware Hubert YoshidaAtthulaiNo ratings yet

- Home Alone 2Document2 pagesHome Alone 2elle maxNo ratings yet

- Annual Financial Statement & Explanatory Memorandum of Haryana, 2018-19 Up To 2023-24Document45 pagesAnnual Financial Statement & Explanatory Memorandum of Haryana, 2018-19 Up To 2023-24Naresh KadyanNo ratings yet

- Leasehold EstatesDocument1 pageLeasehold EstatesflorinaNo ratings yet

- The Horror Film Genre: An OverviewDocument28 pagesThe Horror Film Genre: An OverviewJona FloresNo ratings yet

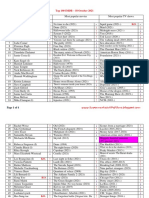

- Top 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021Document4 pagesTop 100 IMDB - 18 October 2021SupermarketulDeFilmeNo ratings yet

- Vham-Bai 3-The Gift of The MagiDocument20 pagesVham-Bai 3-The Gift of The MagiLý Thị Thanh ThủyNo ratings yet

- Course: Advanced Network Security & Monitoring: Session 5Document18 pagesCourse: Advanced Network Security & Monitoring: Session 5Sajjad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Topic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraDocument8 pagesTopic-Act of God As A General Defence: Presented To - Dr. Jaswinder Kaur Presented by - Pulkit GeraPulkit GeraNo ratings yet

- Guilty Gear XX Drama CD: Night of KnivesDocument35 pagesGuilty Gear XX Drama CD: Night of KnivesMimebladeNo ratings yet

- What Is An Attempt To Commit A Crime?Document7 pagesWhat Is An Attempt To Commit A Crime?Anklesh MahuntaNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument35 pagesINTRODUCTIONTarakasish GhoshNo ratings yet

- CRPC Syllabus 2017 Batch (1908)Document8 pagesCRPC Syllabus 2017 Batch (1908)soumya100% (1)

- Twilight (TwilDocument3 pagesTwilight (TwilAnn RamosNo ratings yet

- Gov't vs. El Hogar FilipinoDocument73 pagesGov't vs. El Hogar FilipinoElizabeth Joy CortezNo ratings yet

- Getting Past Sexual ResistanceDocument6 pagesGetting Past Sexual ResistanceNuqman Tehuti ElNo ratings yet

- 9 Raisin in The Sun Reading Questions Act I Scene 1Document3 pages9 Raisin in The Sun Reading Questions Act I Scene 1api-550307076No ratings yet

- BasicBuddhism Vasala SuttaDocument4 pagesBasicBuddhism Vasala Suttanuwan01No ratings yet

- Datatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 581Document6 pagesDatatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 581Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Star Paper Corporation vs. Simbol 487 SCRA 228 G.R. No. 164774 April 12 2006Document13 pagesStar Paper Corporation vs. Simbol 487 SCRA 228 G.R. No. 164774 April 12 2006Angelie FloresNo ratings yet

- Session 16 EtiquettesDocument56 pagesSession 16 EtiquettesISMCSistersCircleNo ratings yet

- 50 Cent SongsDocument9 pages50 Cent SongsVincent TalaoNo ratings yet

- People's Trans East v. Doctors of New MillenniumDocument3 pagesPeople's Trans East v. Doctors of New MillenniumJayson RacalNo ratings yet

- 42 Facts About Jackie RobinsonDocument8 pages42 Facts About Jackie Robinsonapi-286629234No ratings yet

- First Integrated Bonding and Insurance Vs HernandoDocument1 pageFirst Integrated Bonding and Insurance Vs HernandodelbertcruzNo ratings yet

- 39 Clues Discussion QuestionsDocument2 pages39 Clues Discussion Questionsapi-26935172850% (2)

- Castle On The HillDocument6 pagesCastle On The HillEmilia Scarfo'No ratings yet

- Investigative Report of FindingDocument34 pagesInvestigative Report of FindingAndrew ChammasNo ratings yet

- 7th Officers Meeting July 3, 2022Document7 pages7th Officers Meeting July 3, 2022Barangay CentroNo ratings yet

- Downloadable Diary February 27thDocument62 pagesDownloadable Diary February 27thflorencekari78No ratings yet

- Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsFrom EverandMaking Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsNo ratings yet

- Rejected Princesses: Tales of History's Boldest Heroines, Hellions, & HereticsFrom EverandRejected Princesses: Tales of History's Boldest Heroines, Hellions, & HereticsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (68)

- The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man's WorldFrom EverandThe Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man's WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (195)

- Care Work: Dreaming Disability JusticeFrom EverandCare Work: Dreaming Disability JusticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (147)

- Does Jesus Really Love Me?: A Gay Christian's Pilgrimage in Search of God in AmericaFrom EverandDoes Jesus Really Love Me?: A Gay Christian's Pilgrimage in Search of God in AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Queer Magic: LGBT+ Spirituality and Culture from Around the WorldFrom EverandQueer Magic: LGBT+ Spirituality and Culture from Around the WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- UnClobber: Rethinking Our Misuse of the Bible on HomosexualityFrom EverandUnClobber: Rethinking Our Misuse of the Bible on HomosexualityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Gay Sex Stories: The Kinky Erotica CollectionFrom EverandGay Sex Stories: The Kinky Erotica CollectionRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyFrom EverandThe End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (126)

- The Future Is Disabled: Prophecies, Love Notes and Mourning SongsFrom EverandThe Future Is Disabled: Prophecies, Love Notes and Mourning SongsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (24)

- Family Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of CareFrom EverandFamily Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of CareRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity 10th Anniversary EditionFrom EverandCruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity 10th Anniversary EditionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay RevolutionFrom EverandStonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay RevolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (49)

- The Gay Agenda: A Modern Queer History & HandbookFrom EverandThe Gay Agenda: A Modern Queer History & HandbookRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (9)

- Can You Be Gay and Christian?: Responding With Love and Truth to Questions About HomosexualityFrom EverandCan You Be Gay and Christian?: Responding With Love and Truth to Questions About HomosexualityNo ratings yet

- Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present DayFrom EverandQueer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present DayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (61)

- Baba Yaga's Book of Witchcraft: Slavic Magic from the Witch of the WoodsFrom EverandBaba Yaga's Book of Witchcraft: Slavic Magic from the Witch of the WoodsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Lust Unearthed: Vintage Gay Graphics From the DuBek CollectionFrom EverandLust Unearthed: Vintage Gay Graphics From the DuBek CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)