Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Al Qaeda Vs United States: Al Qaeda's Proxy War On America

Uploaded by

James ArtreOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Al Qaeda Vs United States: Al Qaeda's Proxy War On America

Uploaded by

James ArtreCopyright:

Available Formats

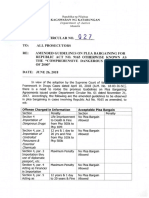

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Al Qaeda

vs

United States

Al Qaedas Proxy War on America

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Al Qaedas Proxy War on America

A "proxy war" is one where someone else is (knowingly or

unknowingly) doing the fighting and dying for you. Our decade

long "proxy war" against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan is an

example. We do have a little problem today in that the Afghanis

we armed, funded, and trained in the 1980s are now fighting

against us in Afghanistan and in Iraq. However, we have a much

bigger problem:

Al Qaeda and Heroin

As of February 2001, under Mullah Omar and the Taliban, opium

was eliminated from Afghanistan. His enforcement methods left

much to be desired by the ACLU. The mullah's enforcers would

just about launch an RPG up your bottom if they saw poppies in

your fields.

Today, the opium crop in Afghanistan is larger than ever before

in the country's entire history (Thousands of "coalition troops"

not withstanding). In fact, the crop has hit an ever larger

historic record size each year we have been in Afghanistan. The

opium is converted into heroin, it is sold, and the money is

then used to fund their projects.

The Mexican drug cartels control not just the smuggling of drugs

but most of Mexico's illegal immigration into the USA (and vast

portions of the Mexican government including much of Mexico's

Regular Army). The Mexican drug cartels have no interest

whatsoever in letting Al Qaeda send bands of wild eyed

terrorists across our southern border and us, anymore then they

do closing our southern border to their drug smuggling business.

What the cartels do want to do is keep their links to Muslim

drug lords and to illegal alien smuggling rings a secret. They

are not trying to keep it a secret from the US government or the

CIA or the DEA. Our government and its agencies know all about

it. The cartels want to keep it secret only from the public.

That may seem odd but it is the way it works. The "ground zero"

for media investigations of these terror networks is Mexico. The

simplest way to discourage reporters in Mexico from reporting is

to kill them.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Today, more reporters are killed in Mexico than anyplace else on

earth except Iraq. Mexican news media have even been hosed-down

with machine guns. The cartels have made it clear they will

silence any inquisitive U.S. media. The US media now stays north

of the border. Confirmation comes from the Voice of America -

broadcasting to foreign lands - and the U.S. Ambassador to

Mexico himself.

As a footnote, the British flooded China with opium as a Weapon

of Mass Destruction -- the British Opium Wars -- in the 1840s

and then again in the 1850s. A third party -- Russia -- then

"seized the moment," took advantage of China's drug sodden

situation, and stole 400,000 square miles of China without

firing a shot. That is how Russia spread all the way to

Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. If you think China has

forgotten, don't.

Nearly all of the methamphetamine flooding America is made in

Mexico by the drug cartels, and the raw materials are shipped in

from Communist China.

Thousands of Chinese are involved in this drug business. This

example is special in that Mr. Ye Gon has admitted the

involvement in his methamphetamine enterprise of people at the

highest levels of the Mexican government.

Al Qaeda has found that they do not have to do much of anything

to kill Americans, except fund the drug cartels with more than a

billion dollars in heroin a year.

A billion dollars may seem an impossible number but it is small

change in Mexico's drug profits. Mr. Ye Gon (above) was found to

have over $207 million in U.S. currency stashed just in one

closet in his house in Mexico. When he was arrested, he was

living in Maryland not five miles from the U.S. Capitol

building.

Muslim heroin is not the weapon - it is the funding source. The

yearly opium crop in Afghanistan is worth over three billion

dollars. (See Opium PDF Research Document below). Not all of

that cash goes to the drug cartels, but a billion of it

certainly does.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

At first, al Qaeda tried to convince the drug cartels to allow

them to poison the cocaine being sent to America. The drug

cartels thought this was a really bad idea (because then much of

their market and trafficking infrastructure -- which took them

years to cultivate -- would be quite dead).

Al Qaeda and the cartels realized that instead, increasing the

flow of drugs across the border would be a better idea because

then there would be more addicts who were a drain on society and

the ancillary crime associated with drug trafficking would help

bankrupt our cities.

The best weapon for this new venture is methamphetamine.

Marijuana is one of Mexico's largest revenue generators, but its

effect on American society is tactical, not strategic.

1. Methamphetamine is a strategic weapon.

2. Illegal aliens are a strategic weapon.

A tactical weapon is one that offers an immediate result and

where the effect is usually quite localized. A strategic weapon

is one that destroys an enemy's economy, or cities, or

infrastructure, and even its government and does not have to

offer immediate results.

Al Qaeda: A History Lesson Well Learned

Emperor of China Declares War on Drugs

Lin Tse-hs, the governor of the Chinese province of Hu-Huang,

was an accomplished administrator and bureaucrat who wrote

stylized Confucian poetry in his spare time.

During his long career, 53-year-old Lin had acquired a

reputation as a man who could be counted on to do the right

thing in a difficult situation.

His high degree of morality and integrity had earned him the

nickname Lin the Clear Sky, and his opinions were highly

regarded at the court of Chinese Emperor Tao-kuang.

In October 1838, Lin Tse-hs was summoned to the Imperial Palace

in Peking, where the Emperor personally assigned him to stamp

out opium addiction in China.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Lin accepted the assignment, knowing that it represented one of

the most difficult problems faced by the Chinese empire. The

sale of opium had been made illegal in China in 1800, but the

black-market narcotics trade flourished in defiance of the law,

and there were an estimated two million Chinese opium addicts.

Addiction was especially common around the port city of Canton,

where foreign merchants smuggled large quantities of the

narcotic drug into China.

Commissioner Lin launched his anti-drug campaign in Canton,

where he set up headquarters and took command of the local naval

forces. On March 10, 1839, Lin proclaimed that the opium trade

would no longer be tolerated in Canton, and he began arresting

known opium dealers in the local schools and naval barracks.

Those found guilty of purchasing, possessing or selling opium

were sentenced to public execution by strangulation. Let no one

think, Lin proclaimed, that this is only a temporary effort on

behalf of the Emperor. We will persist until the job is

finished.

Lin consulted with local physicians and established a treatment

center near Canton. He encouraged opium addicts to enroll there

under amnestyto shed their habit. To combat the popular belief

that opium addiction was an impossible habit to break, Lin

frequently told the story of a man he had met who had been an

addict for thirty years, smoking an ounce of opium a day, but

who managed to give it up. Soon, Lin claimed, his cheeks began

to fill out and the strength came back into his limbs.

Lins next move was to crack down on foreign smugglers of opium.

He knew that very little opium was grown in China. Most opium

was grown in British India, where the drug was a legal

commodity. If Lin could stop foreign merchants from smuggling

opium into his country, then Chinas addiction problem would be

solved.

Lin knew that the opium was brought to China in large British

clipper ships, which also carried legal trade items. The cargo

masters of these ships sold their opium to clandestine Chinese

buyers at Lintin Island in Canton Bay. After the foreign

merchants unloaded their contraband cargo, they proceeded

peacefully up the Pearl River to Canton, where they held permits

to buy tea and silk, and to sell a variety of legal trade goods.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

To the foreign clipper ships anchored at Canton, Commissioner

Lin sent messages demanding that they turn over all of the opium

they had aboard, as well as any supplies of the drug that might

be stored at Lintin Island. He also commanded them to sign

guarantees promising never to bring opium to China again, on

pain of trial and execution if found guilty.

The foreign traders were given three days to comply with

Commissioner Lins demands, but they seemed to take the

situation very lightly and made no move to turn over any opium.

Lin guessed that the foreigners were counting on corrupt Chinese

officials to protect them. Many Cantonese officials, including

the viceroy and high ranking naval commanders, were secretly

accepting bribes, called squeeze money from the western

merchants; some were even using Imperial navy vessels to move

the contraband drug ashore.

On the morning of March 25, 1839, Commissioner Lin gave the

opium smugglers a demonstration of the the seriousness of his

intent. He ordered the suspension of all trade with the western

merchants, who lived together in a small neighborhood of

waterfront homes, offices, and trading docks in Canton.

Lins troops surrounded the foreign neighborhood, building

barricades across the streets to prevent Chinese people from

visiting the docks. Three rows of armed Chinese patrol ships

lined up in the river opposite the trading houses. The foreign

community was informed that it was being held in detention until

the opium trade was suppressed.

Lins action was protested by the ranking British naval officer

in the Chinese port, Captain Charles Elliot. The merchants,

Elliot asserted, had the full support of the British government,

and were not bound to obey the laws of China.

Commissioner Lin laid down the terms under which the foreign

merchants could regain their freedom and their right to trade in

Canton. First, they must turn over all of the opium concealed

aboard their ships, then they must sign a binding pledge not to

bring any more opium to China in the future. Until these

requirements were met, the foreigners would not be permitted to

purchase any tea, rice, or silk for export.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

On March 27, the merchants agreed to surrender their opium to

Commisioner Lin. When Lin informed Emperor Tao-kuang of his

success, he was rewarded with an exquisitely prepared dinner of

roebuck venison, a message signifying Promotion Assured, and a

hand painted silk scroll from the Emperor bearing the characters

Good Luck, Long Life.

During the next two months, over two and a half million pounds

of processed opium were delivered under tight security from the

merchant ships to the Chinese mainland.

Commissioner Lin was faced with the problem of disposing of the

enormous stockpile of opium which he had confiscated. After

consulting with Cantonese engineers and chemists, Lin had three

large trenches dug along the seacoast. Each trench measured

seventy five wide by one hundred fifty feet long, was seven feet

deep, and was lined with flagstones and rough-hewn timbers. The

three trenches were surrounded by a tall bamboo fence.

On the first day of June, 1839, Commissioner Lin composed a

ritual address to the Spirit of the South China Sea. He advised

the spirit that he should shortly be dissolving opium and

draining it off to the great ocean, and suggested that all sea

creatures should retreat to deeper water to avoid being

contaminated, until the opium was completely run off.

On June 3, the destruction of the foreign opium began. The

trenches were filled with water, and the first chests of opium

were broken open and thrown in to soak. Next, large quantities

of salt and lime were dumped into the mixture. The ensuing

chemical reaction heated and liquefied the opium, releasing

clouds of nauseating gas. A team of five hundred closely guarded

laborers with shovels and hoes stirred the slowly decomposing

material and ran it off into a stream that led to the sea. The

first worker who was caught trying to steal some opium was

immediately beheaded as a warning to the rest.

For the next two weeks, Commissioner Lin supervised the

methodical destruction of the opium, or foreign mud, from a

pavilion set up near the trenches. When he advised the Emperor

that the work was finished, Lin received the warm reply, This

is something that is greatly delightful to the hearts of

mankind.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Despite his success, Commissioner Lin could see that the British

merchants were not yet willing to abide by the laws of China.

Trying to escape from Lins authority, some merchants had moved

away from Canton and sailed down the Canton estuary to the

Portuguese-controlled port of Macao, where it seemed they were

intending to resume smuggling opium. Other British ships

anchored near the sparsely inhabited island of Hong Kong, at the

mouth of the estuary.

On July 12, a Chinese villager was killed by a rampaging gang of

drunken British seamen who had come ashore at Kowloon, a

mainland village near Hong Kong. Lin demanded that the men

responsible for the murder be turned over to him for punishment.

Captain Elliot responded that the seamen could only be tried

under British jurisdiction.

Captain Elliot then tried the sailors himself, with results that

were not satisfactory to Commissioner Lin. One seaman was

acquitted of a murder charge for lack of evidence, and five

others were found guilty of participation in a general riot.

When Lin again demanded that the guilty men be delivered to

Canton for justice, Elliot sent word that the men would all be

appropriately punished when they returned to England.

To force Elliot to submit to his demands, Lin ordered that

delivery of all rice, tea, meat and fresh vegetables to the

anchored ships at Macao to be intercepted and cut off.

Freshwater springs that were known to be used by the British at

various points along the coast were poisoned. Large banners were

posted to warn Chinese villagers not to drink from the streams.

Lin then pressured the Portuguese authorities at Macao to evict

the British from their harbor, under penalty of severe trade

restrictions. These drastic measures forced all of the British

ships to retreat from Macao to Hong Kong by the middle of

August.

On August 31, Commissioner Lin learned that the merchant ships

anchored off Hong Kong had been joined by a twenty-eight gun

British frigate. Although this news was not good, Lin, who had

the use of a fleet of Chinese war junks at his disposal, was not

frightened by the arrival of a single British warship.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Lin assumed that his Chinese warships were superior to the ships

of the British navy. He thought that Europeans were primitive

barbarians. British fabrics were inferior to Chinese silk,

British earthenware was inferior to Chinese ceramics, and the

general behavior of British seamen seemed uncivilized, so Lin

assumed that the British navy must be inferior to the Chinese

navy. Lin did not know that even British civilian merchant ships

were armed with cannon that were far deadlier and more accurate

than any of the guns of the Chinese fleet.

On September 4, two British merchant ships and a launch from the

newly arrived warship attacked three Chinese junks that tried to

prevent them from landing at Kowloon to obtain water and

supplies. Although the Chinese warships returned the British

fire, they did no damage to the British ships, and were forced

to retreat after being badly shot up by cannonballs.

The captains of the defeated Chinese junks feared that their

failure would be viewed by higher authorities as a disgraceful

act of cowardice. The captains therefore reported to

Commissioner Lin that they had won a victory and had sunk a

British ship. Commissioner Lin forwarded this version of the

encounter to the Emperor and composed an angry proclamation the

British, warning them that because you have presumptuously

fired upon and attacked our naval cruisers, our army and navy

will now be required to launch a devastating attack upon you,

and you will suffer just punishment at our hands.

Lin informed the Emperor that he was preparing to permanently

drive the merchants away from Hong Kong. By September 22, Lin

had assembled a fleet of eighty junks and fireships at the mouth

of the Pearl River.

Confident that the British were alarmed by his preparations for

naval warfare, Lin wrote a poem noting that a vast display of

Imperial might has shaken all the foreign tribes, and, if they

now confess their guilt, we will not be too hard on them.

Lin ignored messages from Captain Elliot, who impudently

demanded that British merchants be allowed to buy the last crop

of Chinese tea that had been harvested that year.

Commissioner Lin insisted that the British could not enjoy any

of the benefits of legal trade unless they agreed to obey

Chinese laws and stopped importing opium. If the British could

not honor these terms, they were ordered to leave Chinese waters

and never return.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Captain Elliot Refused to Concede

In early November, Lin learned that a second British warship, an

eighteen-gun frigate, had joined the British merchant fleet at

Hong Kong. On November 3, the two British warships approached

the Chinese fleet with a sealed letter, demanding supplies and

the immediate resumption of trade.

The admiral of the Chinese fleet returned the merchants letter

unopened, at which point the frigates attacked the anchored

Chinese fleet. The British immediately sank five of the largest

Chinese war junks and severely damaged many others in an attack

that lasted just under 45 minutes.

Commissioner Lin now faced serious difficulties. If he

truthfully reported his defeat to the Emperor, he was likely to

be disgraced and punished. He therefore kept his report of the

battle brief and vague, describing six imaginary smashing

blows that had been inflicted on the impetuous British

barbarians.

Pleased with Lins report, Emperor Tao-kuang gave his thanks.

The Emperor also inquired whether Commissioner Lin had, in fact,

completely stopped the smuggling of opium. Independent reports

had arrived in Peking, claiming that small British boats were

delivering chests of opium to remote villages along the seacoast

north of Canton. The Emperor reminded Lin that his job was to

clear away the opium-evil throughout all of China, not just in

Canton.

Lin assured the Emperor that the despicable foreign drug trade

was rapidly drawing to a close. He spent the next several months

fortifying Canton harbor by sinking barges loaded with stones at

its entrances. He also purchased an American sailing ship and

outfitted it with cannon supplied by some enterprising

Portuguese merchants.

In the beginning of June 1840, Lin suddenly found himself

confronting a large British expeditionary force that had come

from Singapore, which included steam-powered gunboats and

thousands of British marines.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

In a report to the Emperor, Lin wrote, English warships are now

arriving at Canton. Although it is certain that they will not

venture to create a disturbance here, I am certain that they

will, like great rats, attempt to shelter the vile sellers of

opium. Still confident that the Chinese coast-guard could

prevail in the event of trouble, Lin concluded People say that

our junks and guns are no match for the British.... But they do

not know!

Commissioner Lins forces, however, proved to be no match for

the invaders, who immediately imposed a blockade on the Canton

estuary, then attacked and took control of strategically

important sites along the China coast.

The British commander sent a sobering message to Emperor Tao-

kuang in Peking, demanding satisfaction and redress for

Commissioner Lins actions at Canton.

On August 21, 1840, the Emperor dismissed Lin Tse-hs from his

post as Imperial Commissioner.

You have caused this war by your excessive zeal. the Emperor

wrote.

You have lied to us, disguising in your dispatches the true

color of affairs. Instead of helping us, you have only caused

confusion to arise. Now, one thousand unending problems are

sprouting. You have behaved as if your arms are tied. You are no

better than a wooden dummy. As we think about your grievous

failings, we become furious, and then melancholy.

Stripped of his title, Lin Tse-hs was exiled to the isolated

northern frontier province of Ili, where he was given the task

of supervising large scale irrigation and flood control

projects.

Lin Tse-hs gradually recovered from the disgrace of his failure

to put an end to the opium trade. Ten years after his dismissal,

the Emperor again summoned him into service. Lin was reinstated

as Imperial Commissioner, and assigned to travel to the

rebellious province of Kwangsi to negotiate with rebel factions.

Lin Tse-hs collapsed and died while en route to Kwangsi on

November 22, 1850, at the age of 67.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

The successive Imperial Commissioners who replaced Lin Tse-hs

in Canton were unable to stop the opium traffic. In conflicts

known as the First and Second Opium Wars, British naval and

marine forces seized control of Hong Kong, ravaged the Chinese

coastline and briefly occupied the capital city of Peking.

In 1858 the Chinese government, bowing to British demands,

reluctantly legalized the importation of opium.

================================================================

In light of recent revelations regarding Malik Obama President

Barack Obamas half-brother and his dealings and associations

with Muslim Brotherhood operatives, further investigation into

any possible connections between him (BHO) and his brother, is a

matter of national security.

President Barack Obamas refusal to stop the invasion of illegal

aliens, and therefore drugs, along the United States border with

Mexico is also cause for suspicion. The fact that US authorities

estimate that 60,000 to 80,000 undocumented children will cross

the border without their parents this year, a move by South

American parents to save their children from muslim terrorists

and drugs, only leads credence to the Al Qaeda/Mexican drug

cartel connection.

The legalization of Marijuana in US States, such as Colorado and

Washington, only reiterate the importance of learning from

history, then taking action upon it. President Obamas attorney

General, Eric Cantor, refusal to step in and stop the sale of an

illegal drug (Marijuana) over the counter only heightens the

suspicions of the Obama/Muslim Connection.

Meanwhile, the war on America continues...

================================================================

SOURCES:

Obamas Ties to Wahhabist Muslim Terrorists:

http://shoebat.com/2013/05/28/confirmed-barack-obamas-brother-

in-bed-with-man-wanted-by-international-criminal-court-icc-for-

crimes-against-humanity/

US Border Patrol:

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/Border_Patrol90e.htm

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Border Patrol Afghan Opium Crop

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/Border_Patrol_%20Afghan%20Opium%20

Crop.htm

Afghanistan, Opium and the Taliban:

http://opioids.com/afghanistan/index.html

Reporters with out Borders: Mexico http://en.rsf.org/mexico.html

Voice of America

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/Border_Patrol_VOA%20Mexican%20Drug

%20Traffickers.htm

US Ambassador Antonio O. Garza

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/Border_Patrol_US%20Embassy%20Mexic

an%20Drug%20Traffickers.htm

England and China: The Opium Wars, 1839-60

http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/opiumwars/opiumwars1.

html

Mexico Seeks Extradition of Drug Making Suspect:

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/Border_Patrol_Chinese%20%20Methamp

hetamine.htm

The Taliban Opium War:

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/07/09/070709fa_fact_ande

rson

Opium PDF Research Document:

http://www.usborderpatrol.com/WDR_2007_3.1.1_afghanistan.pdf

Paul Chrastina: http://www.oldnewspublishing.com/opium.htm

Washington State Legalizes Marijuana: http://rt.com/usa/171280-

washington-state-legal-marijuana-sell/

The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes. by Arthur Waley. George

Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1958

Commissioner Lin and the Opium War. by Hsin-pao Chang. Harvard

U. Press, 1964.

The Chinese Opium Wars. by Jack Beeching. Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, 1975.

The Opium Wars in China. by Edgar Holt. Putnam, 1964.

File: FYEO-AQPWUS-015

Foreign Mud. by Maurice Collis. W.W. Norton Co., Inc., 1946.

British Trade and the Opening of China, 1800-1842. by Michael

Greenberg. Cambridge University Press, 1951.

Strangers at the Gate: Social disorder in South China, 1839-

1861. by Frederic Wakeman, Jr. University of California Press,

1966

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Shadow GovernmentDocument11 pagesThe Shadow GovernmentJames Artre100% (4)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Jefferson Lies - Taking On The CriticsDocument8 pagesThe Jefferson Lies - Taking On The CriticsJames Artre100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- IRS Scandal Has Ties To Obama Foundation and Muslims in KenyaDocument22 pagesIRS Scandal Has Ties To Obama Foundation and Muslims in KenyaJames Artre100% (1)

- Republic vs. Democracy: Rule by Law vs. Rule by MajorityDocument5 pagesRepublic vs. Democracy: Rule by Law vs. Rule by MajorityJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Chaos in America: Inside The Obama InsurgencyDocument14 pagesChaos in America: Inside The Obama InsurgencyJames Artre100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Most Dangerous Man in The WorldDocument2 pagesThe Most Dangerous Man in The WorldJames Artre100% (2)

- POPS Plan - 08032022Document136 pagesPOPS Plan - 08032022Verne Gonzales Jr.No ratings yet

- Atty. Robert Aldrin B. Ortiz: Mr. Jose AbusadoDocument16 pagesAtty. Robert Aldrin B. Ortiz: Mr. Jose AbusadoRA OrtizNo ratings yet

- Revenge PornDocument26 pagesRevenge PornmedialawsNo ratings yet

- Rule 128 - General ProvisionsDocument3 pagesRule 128 - General ProvisionsJohn Ramil RabeNo ratings yet

- Company Data Protection PolicyDocument2 pagesCompany Data Protection Policyhehersonlaggui100% (1)

- Attention Grabbing Headlines For Travel BloggersDocument16 pagesAttention Grabbing Headlines For Travel BloggersJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- PNP Investigator's Handbook For New Normal - ApprovedDocument44 pagesPNP Investigator's Handbook For New Normal - ApprovedJanice Layam Puedan100% (1)

- Cyber Maritime SecurityDocument55 pagesCyber Maritime SecurityCostas VarouxisNo ratings yet

- Castro Vs MendozaDocument2 pagesCastro Vs MendozaGeneva Mica NodaloNo ratings yet

- Project Playbook - Internet Safety GuideDocument17 pagesProject Playbook - Internet Safety GuideTheresa LongoNo ratings yet

- DOJ Plea Bargaining 2018 GuidelinesDocument11 pagesDOJ Plea Bargaining 2018 GuidelinesDemz CrownNo ratings yet

- How To Defeat A Liberal PDFDocument13 pagesHow To Defeat A Liberal PDFJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- How To Overcome Every Temptation in LifeDocument6 pagesHow To Overcome Every Temptation in LifeJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- Islam Is A Government Dictatorship Housed in ReligionDocument3 pagesIslam Is A Government Dictatorship Housed in ReligionJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- 2012 Party Platform ComparisonsDocument2 pages2012 Party Platform ComparisonsJames Artre0% (1)

- Harold Estes and FriendsDocument3 pagesHarold Estes and FriendsJames ArtreNo ratings yet

- Bihar Liquor ProhibitionDocument1 pageBihar Liquor ProhibitionAbhishek RajNo ratings yet

- Sentencing Guidelines of UK, USA and India: Hidayatullah National Law Univeristy, RaipurDocument18 pagesSentencing Guidelines of UK, USA and India: Hidayatullah National Law Univeristy, RaipurSaurabh BaraNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 228886 August 8, 2018 People of The Philippines vs. Charlie Flores, Daniel Flores and Sammy FloresDocument1 pageG.R. No. 228886 August 8, 2018 People of The Philippines vs. Charlie Flores, Daniel Flores and Sammy FloresMarklawrence FortesNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE Vs NEPOMUCENODocument2 pagesPEOPLE Vs NEPOMUCENOEthan KurbyNo ratings yet

- Criminal CircumstancesDocument4 pagesCriminal CircumstancesAilynne Joy Rojas LimNo ratings yet

- Carmen Liwanag, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and The People of The PHILIPPINES, Represented by The Solicitor General, RespondentsDocument3 pagesCarmen Liwanag, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and The People of The PHILIPPINES, Represented by The Solicitor General, RespondentsJillandroNo ratings yet

- Revised PADS As of Nov 9 2018Document79 pagesRevised PADS As of Nov 9 2018Angela Buid InongNo ratings yet

- People V AvendanoDocument3 pagesPeople V AvendanoistefifayNo ratings yet

- Dharmendra Kumar-THDocument10 pagesDharmendra Kumar-THTauheedAlamNo ratings yet

- The Case of The Missing PenDocument5 pagesThe Case of The Missing PenStefan KamphNo ratings yet

- Mins 11020709 Ohio State Board of Pharmacy Minutes, Courtesy of Lindon & LindonDocument23 pagesMins 11020709 Ohio State Board of Pharmacy Minutes, Courtesy of Lindon & LindonJames LindonNo ratings yet

- BAR Don Reviewer CriminalLawDocument49 pagesBAR Don Reviewer CriminalLawKhenett Ramirez PuertoNo ratings yet

- Foreign Painters and Their WorksDocument28 pagesForeign Painters and Their WorksSheenah LA0% (2)

- 2.1 EngDocument26 pages2.1 EngN Malbas100% (2)

- Rep. Jeff Hoverson Minot Airport Incident ReportsDocument4 pagesRep. Jeff Hoverson Minot Airport Incident ReportsRob PortNo ratings yet

- 2021 Annual IMB Piracy ReportDocument55 pages2021 Annual IMB Piracy ReportJessica Hendra HonggoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 163586 (Castro Vs Deloria) PDFDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 163586 (Castro Vs Deloria) PDFHannika SantosNo ratings yet

- Kaspersky LabDocument321 pagesKaspersky Labelectromacnetist9537No ratings yet

- 3:12-cv-3005 #36Document107 pages3:12-cv-3005 #36Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Brockton Police Log May 23, 2019Document16 pagesBrockton Police Log May 23, 2019BBNo ratings yet