Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Carino Vs NLRC GR No 91086

Uploaded by

Breth19790 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

223 views5 pagesThe Supreme Court of the Philippines upheld the decision of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) that modified the decision of the Labor Arbiter in the case of Virgilio S. Cariño vs. National Labor Relations Commission, Harrison Industrial Corporation, and Harrison Industrial Workers' Union. The NLRC found just cause for Cariño's dismissal based on his expulsion from the union due to charges of mismanaging union affairs and conspiring with the company. While the manner of dismissal violated due process, the NLRC and Supreme Court affirmed liability of the company and union to pay separation pay to Cariño.

Original Description:

labor

Original Title

2. Carino vs NLRC Gr No 91086

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Supreme Court of the Philippines upheld the decision of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) that modified the decision of the Labor Arbiter in the case of Virgilio S. Cariño vs. National Labor Relations Commission, Harrison Industrial Corporation, and Harrison Industrial Workers' Union. The NLRC found just cause for Cariño's dismissal based on his expulsion from the union due to charges of mismanaging union affairs and conspiring with the company. While the manner of dismissal violated due process, the NLRC and Supreme Court affirmed liability of the company and union to pay separation pay to Cariño.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

223 views5 pagesCarino Vs NLRC GR No 91086

Uploaded by

Breth1979The Supreme Court of the Philippines upheld the decision of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) that modified the decision of the Labor Arbiter in the case of Virgilio S. Cariño vs. National Labor Relations Commission, Harrison Industrial Corporation, and Harrison Industrial Workers' Union. The NLRC found just cause for Cariño's dismissal based on his expulsion from the union due to charges of mismanaging union affairs and conspiring with the company. While the manner of dismissal violated due process, the NLRC and Supreme Court affirmed liability of the company and union to pay separation pay to Cariño.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

1

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 91086 May 8, 1990

VIRGILIO S. CARIO petitioner,

vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, HARRISON INDUSTRIAL CORPORATION and HARRISON

INDUSTRIAL WORKERS' UNION, respondents.

Federico C. Leynes for petitioner.

Banzuela, Flores, Miralles, Raeses Sy, Taquio & Associates for respondent Union.

Armando V. Ampil for respondent Harrison.

R E S O L U T I O N

FELICIANO, J.:

Petitioner asks the Court to declare null and void a Decision dated 26 May 1989 of the National Labor

Relations Commission (NLRC) in NLRC Case No. NCR-00-09-03225-87 and to reinstate the Decision of the

Labor Arbiter which the NLRC had modified.

Petitioner Cario was the former President of private respondent Harrison Industrial Workers' Union

("Union"). Because he was widely believed to have grossly mismanaged Union affairs, the other officers of

the Union formed an investigating committee and several times invited petitioner Cario to answer the

complaints and charges against him. These charges were, principally:

1. Conspiring with the company during the negotiation of the CBA, resulting in, among other things, Article

22 entitled "Retirement" which provided for retirement pay of one (1) day's basic salary for every year of

service.

2. Paying attorney's fees to Atty. Federico Leynes, Union counsel, out of Union funds without obtaining

corresponding receipts therefor.

3. Unilaterally increasing the membership dues by an additional P17.00 per member in order to pay

increased attorney's fees.

4. Concealing the CBA, failure to present and to explain the provisions of the same prior to ratification by the

union membership.

5. Refusal to turn over the custody and management of Union funds to the Union treasurer.

Petitioner Cario, however, failed to respond to the calls or invitations made by the investigating committee.

Finally, the investigation committee caged a general membership meeting on 11 June 1987. At this general

membership meeting, the charges against petitioner were presented and discussed and the Union decided to

file a petition for special election of its officers.

On 16 June 1987, a petition for special election of officers was filed by the Union with the Bureau of Labor

Relations, Department of Labor and Employment. Several hearings were field at the BLR always with due

notice to petitioner Cario petitioner, however, failed to appear even once.

On 5 August 1987, a general Union membership meeting was held for the impeachment of Cario. The

general membership found Cario guilty of the above-mentioned charges and decided to expel him from the

Union and to recommend his termination from employment. Atty. Federico Leynes also ceased to be counsel

for the Union.

The Union accordingly informed private respondent Harrison Industrial Corporation ("Company") of the

expulsion of petitioner Cario from the Union and demanded application of the Union Security Clause of the

then existing Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) on 15 September 1987. Petitioner Cario received a

letter of termination from the Company, effective the next day.

Petitioner Cario, now represented by Atty. Leynes, the former lawyer of the Union, filed a complaint for

illegal dismissal with the Labor Arbiter.

In a Decision dated 7 October, 1988, the Labor Arbiter held that there was no just cause for the dismissal of

petitioner Cario, none of the causes for suspension or dismissal of Union members enumerated in the

Union's Constitution and By-Laws being applicable to petitioner's situation. The Labor Arbiter also held that

the manner of petitioner's dismissal had been in disregard of the requirements of notice and hearing laid

down in the Labor Code. The Labor Arbiter ordered petitioner's reinstatement with full backwages and

payment of attorney's fees, the monetary liability to be borne solidarily by the Company and the Union.

The Company and the Union went on appeal before the public respondent National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC). The NLRC, in a Decision promulgated on 26 May 1989, reversed the Labor Arbiter's

award. The NLRC noted that petitioner Cario had merely denied the serious charges of mismanagement

preferred against him, as set out in the affidavit of Dante Maroya, the incumbent President of the Union,

which affidavit had been adopted by the Union as its position paper in the proceedings before the Labor

2

Arbiter. The NLRC held Cario's silence as "tantamount to [an] admission of guilt" and as constituting the

ultimate cause for his dismissal. However, the NLRC agreed with the Labor Arbiter's finding that the manner

of petitioner Cario's dismissal was inconsistent with the requirements of due process. The NLRC

accordingly found the Company and the Union solidarily liable, "by way of penalty and financial assistance",

to petitioner Cario for payment of separation pay, at the rate of one-half (1/2) month's salary for each year

of service.

In the instant Petition for Certiorari, petitioner Cario basically seeks reinstatement of the Decision of the

Labor Arbiter.

1. Petitioner Cario contended that the NLRC had erred in taking cognizance of the Union's admittedly late

appeal. We agree, however, with the Solicitor General that it is a settled principle of remedial law that

reversal of a judgment obtained by a party appealing from it also benefits a co-party who had not appealed,

or who had appealed out of time, where the rights and liabilities of both parties under the modified decision

are so interwoven and inter-dependent as to be substantively inseparable.

1

In the instant case, the NLRC could take cognizance of the late appeal of the Union, considering that the

lawfulness of petitioner Cario's dismissal by the Company could be determined only after ascertaining,

among other things, the validity of the Union's act of expelling Cario from its membership. In other words,

the Company having seasonably appealed the Labor Arbiter's Decision and the Company's and the Union's

liability being closely intertwined the NLRC could properly take account of the Union's appeal even though

not seasonably filed.

2. The NLRC in effect held that there had been just cause for petitioner Cario's dismissal. The Court

considers that the NLRC was correct in so holding, considering the following documentary provisions:

a) Article II, Sections 4 and 5 of the Collective Bargaining Agreement between the Company and the Union

provided as follows:

Sec. 4. Any employee or worker obliged to join the UNION and/or maintain membership

therein under the foregoing sections who fails to do so and/or maintain such membership

shall be dismiss without pay upon formal request of the UNION.

Sec. 5. Any UNION member may be suspended and/or expelled by the UNION for:

a) Non-payment of dues or special assessment to the UNION.

b) Organizing or joining another UNION or affiliating with a labor federation.

c) Commission of a crime as defined by the Revised Penal Code against any UNION officer in

relation to activities for and in behalf of the UNION.

d) Participation in an unfair labor practice or any derogatory act against the UNION or any of

its officers or members; and

e) Involvement in any violation of this Agreement or the UNION's Constitution and By-Laws.

The UNION assumes full and complete responsibility for all dismiss of any worker/employee effected by the

UNION and conceded in turn, by the COMPANY pursuant to the provisions hereof.

The UNION shall defend and hold the COMPANY free and harmless against any and all claims the dismissed

worker/employee might bring and/or obtain from the Company for such dismissal.

2

(Emphasis supplied)

b) The Constitution of the Union contains the following provisions:

(i) Article X Section 5 reads:

ARTICLE X-FEES, DUES SPECIAL ASSESSMENTS, FINES AND OTHER PAYMENTS

xxx xxx xxx

Sec. 5. Special assessments or other extraordinary fees such as for payment of attorney's fees

shall be made only upon a resolution duly ratified by the general membership by secret

balloting.

xxx xxx xxx

(Emphasis supplied.)

(ii) Article XV entitled "Discipline" provides in Section I thereof that:

Sec. 1. Any individual union members and/or union officer may be disciplined or expelled

from the UNION by the Executive Board if the latter should find the former guilty of charges,

based on the following grounds preferred officially against him:

a) Non-payment of dues and other assessments for two (2) months;

b) Culpable violation of the Constitution and By Laws;

c) Deliberate refusal to implement policies, rules and regulations decisions and/or support

the programs or projects of the UNION as laid down by its governing organs or its officers;

and

d) Any act inimical to the interest of the UNION and/or its officers, such as but not limited to

rumor mongering which tends to discredit the name and integrity of the UNION and/or its

officers and creating or causing to create dissension among the UNION members

thereof.

4

(Emphasis supplied.)

3

Article XVI entitled "Impeachment and Recall" specified, in Section 1 thereof, the grounds for impeachment

or recall of the President and other Union officers, in the following terms:

a) Committing or causing the commission directly or indirectly of acts against the interest and

welfare of the UNION;

b) Malicious attack against the UNION, its officers or against a fellow UNION officer or

member;

c) Failure to comply with the obligation to turn over and return to the UNION Treasurer

within three (3) days are [sic] unexpected sum or sum of money received an authorized

UNION purpose;

d) Gross misconduct unbecoming of a UNION officer;

e) Misappropriation of UNION funds and property. This is without prejudice to the filing of an

appropriate criminal or civil action against the responsible officer or officers by any

interested party

f) Willful violation of any provisions on this Constitution or rules, regulations, measures,

resolution and decisions of the UNION.

5

(Emphasis supplied.)

It appears to the Court that the particular charges raised against petitioner Cario, set out earlier, reasonably

fall within the underscored provisions of the foregoing documents. The NLRC impliedly recognized this when

it described the charges of mismanagement against Carino as serious.

The Labor Arbiter, however, also held that petitioner Cario had been deprived of procedural due process on

the union level in view of alleged failure to comply with the required procedure, governing impeachment and

recall proceedings set out in Article XVI, Section 2, of the Constitution of the Union. Article XVI, Section 2

reads as follows:

a) Impeachment or recall proceedings shall be initiated by a formal petition or resolution

signed by at least thirty (30%) percent of all bona fide members of the UNION and addressed

to the Chairman of the Executive board.

b) The Board Chairman shall then convene a general membership fee to consider the

impeachment or recall of an officer or a group of officers, whether elective or appointive

c) UNION officers against whom impeachment or recall charges have been filed shall be given

ample opportunity to defend themselves before any impeachment or recall vote is finally

taken.

d) A majority of all members of the UNION shall be required to impeach or recall UNION

officers.

e) The UNION officers impeached shall ipso facto be considered resigned or ousted from

office and shall no longer be elected nor appointed to any position in the UNION.

f) The decision of the general membership on the impeachment or recall charge shall be final

and executory.

6

The NLRC, for its part, noted that while the prescribed procedural steps had not all been followed or

complied with, still,

Be that as it may, the general membership of the Union had spoken and decided to expel

complainant as Union President and member and ultimately, requested the company to

terminate his services per CBA prescription. It is worthy to note that the charges aired by Mr.

Dante Maroya are serious enough for complainant to specifically respond and explain his side

at the arbitral proceedings below. While it appears that due process was lacking at the plant

level, this was cured by the arbitration process conducted by the Labor Arbiter. Despite the

ample opportunity to explain his side, complainant failed to do so and instead, relied completely

on alleged denial of due process. Complainant's silence in this respect is tantamount to [an]

admission of guilt.

7

(Emphasis supplied.)

It is true that the impeachment of Cario had not been initiated by a formal petition or resolution signed by

at least thirty percent (30%) of an the bona fide members of the Union. A general meeting had, however,

been called to take up the charges against petitioner Carino who had been given multiple opportunities to

defend himself before the investigating committee of the Union officers and before the general Union

members as well as before the Bureau of Labor Relations. Petitioner Cario, however, chose to disregard all

calls for him to appear and defend himself. At the general membership meeting, therefore, petitioner Cario

was impeached and ordered recalled byunanimous vote of the membership. Under these circumstances,

failure to comply literally with step (a) of Article XVI Section 2 of the Union's Constitution must be regarded

as non-material: the prescribed impeachment and recall proceeding had been more than substantially

complied with.

4. Turning now to the involvement of the Company in the dismissal of petitioner Cario we note that the

Company upon being formally advised in writing of the expulsion of petitioner Carino from the Union, in turn

simply issued a termination letter to Cario, the termination being made effective the very next day. We

believe that the Company should have given petitioner Carino an opportunity to explain his side of the

4

controversy with the Union. Notwithstanding the Unions Security Clause in the CBA, the Company should

have reasonably satisfied itself by its own inquiry that the Union had not been merely acting arbitrarily and

capriciously in impeaching and expelling petitioner Cario. From what was already discussed above, it is

quite clear that had the Company taken the trouble to investigate the acts and proceedings of the Union, it

could have very easily determined that the Union had not acted arbitrarily in impeaching and expelling from

its ranks petitioner Cario. The Company offered the excuse that the Union had threatened to go on strike if

its request had not been forthwith granted. Assuming that such a threat had in fact been made, if a strike was

in fact subsequently called because the Company had insisted on conducting its own inquiry, the Court

considers that such would have been prima facie an illegal strike. The Company also pleaded that for it to

inquire into the lawfulness of the acts of the Union in this regard would constitute interference by the

Company in the administration of Union affairs. We do not believe so.

In Liberty Cotton Mills Worker's Union, et al. v. Liberty Cotton Mills, et al.

8

the Court held respondent company

to have acted in bad faith in dismissing the petitioner workers without giving them an opportunity to

present their side in their controversy with their own union.

xxx xxx xxx

It is OUR considered view that respondent company is equally liable for the payment of

backwages for having acted in bad faith in effecting the dismissal of the individual

petitioners. Bad faith on the part of respondent company may be gleaned from the fact that the

petitioner workers were dismissed hastily and summarily. At best, it was guilty of a tortious act,

for which it must assume solidary liability, since it apparently chose to summarily dismiss the

workers at the union's instance secure in the union's contractual undertaking that the union

would hold it "free from any liability" arising from such dismissal.

xxx xxx xxx

While respondent company, under the Maintenance of Membership prevision of the

Collective Bargaining Agreement, is bound to dismiss any employee expelled by PAFLU for

disloyalty, upon its written request, this undertaking should not be done hastily and

summarily. The company acted in bad faith in dismissing petitioner workers without giving

them the benefit of a hearing. It did not even bother to inquire from the workers concerned and

from PAFLU itself about the cause of the expulsion of the petitioner workers. Instead, the

company immediately dismissed the workers on May 29, 1964 in a span of only one day

stating that it had no alternative but to comply with its obligation under the Security

Agreement in the Collective Bargaining Agreement thereby disregarding the right of the

workers to due process, self-organization and security of tenure.

xxx xxx xxx

The power to dismiss is a normal prerogative of the employer. However, this is not without

limitations.The employer is bound to exercise caution in terminating the services of his

employee especially so when it is made upon the request of a labor union pursuant to the

Collective Bargaining Agreement,as in the instant case. Dismissals must not be arbitrary and

capricious. Due process must be observed in dismissing an employee because it affects not

only his position but also his means of livelihood. Employers should therefore respect and

protect the rights of their employees, which include the right to labor. . . .

xxx xxx xxx

(Emphasis supplied.)

In Manila Cordage Company v. Court of industrial Relations, et al.,

10

the Court stressed the requirement of

good faith on the part of the company in dismissing the complainant and in effect held that precipitate action

in dismissing the complainant is indication of lack of good faith.

xxx xxx xxx

The contention of the petitioners that they acted in good faith in dismissing the complainants

and, therefore, should not be held liable to pay their back wages has no merit. The dismissal of

the complainants by the petitioners was precipitate and done with undue haste. Considering

that the so-called "maintainance of membership" clause did not clearly give the petitioners the

right to dismiss the complainants if said complainants did not maintain their membership in the

Manco Labor Union, the petitioners should have raised the issue before the Court of industrial

Relations in a petition for permission to dismiss the complainants.

xxx xxx xxx

(Emphasis supplied.)

5. We conclude that the Company had failed to accord to petitioner Cario the latter's right to procedural due

process. The right of an employee to be informed of the charges against him and to reasonable opportunity

to present his side in a controversy with either the Company or his own Union, is not wiped away by a Union

Security Clause or a Union Shop Clause in a CBA. An employee is entitled to be protected not only from a

5

company which disregards his rights but also from his own Union the leadership of which could yield to the

temptation of swift and arbitrary expulsion from membership and hence dismissal from his job.

The Court does not believe, however, that the grant of separation pay to petitioner Cario was an

appropriate response (there having been just cause for the dismissal) to the failure of the Company to accord

him his full measure of due process. Since petitioner Cario had clearly disdained answering the charges

preferred against him within the Union, there was no reason to suppose that if the Company had held formal

proceedings before dismissing him, he would have appeared in a Company investigation and pleaded his

defenses, if he had any, against the charges against him. There was no indication that the Company had in

fact conspired with the Union to bring about the expulsion and dismissal of petitioner Cario indeed, the

Union membership believed it was Cario who had conspired with the company in the course of negotiating

the CBA. Considering all the circumstances of this case, and considering especially the nature of the charges

brought against petitioner Cario before his own Union, the Court believes that a penalty of P5,000 payable

to petitioner Carino should be quite adequate, the penalty to be borne by the Company and the Union

solidarily The Court also considers that because the charges raised against petitioner and unanswered by

him have marked overtones of dishonesty, this is not a case where "financial (humanitarian) assistance" to

the dismissed employee is warranted.

12

WHEREFORE, the Court DISMISSED the Petition for certiorari for lack of merit but MODIFIED the Decision of

the public respondent National Labor Relations Commission dated 26 May 1989 by eliminating the grant of

separation pay and in lieu thereof imposing a penalty of P5,000.00 payable to the petitioner to be borne

solidarily by the Company and the Union. No pronouncement as to costs.

Fernan, C.J., Gutierrez, Jr., Bidin and Cortes JJ., concur.

You might also like

- 18 - New Philippine Skylanders, Inc. v. DakilaDocument2 pages18 - New Philippine Skylanders, Inc. v. DakilaJesimiel CarlosNo ratings yet

- Tagaytay Highlands International Golf Club Vs Tagaytay Highlands Ees Union (D)Document3 pagesTagaytay Highlands International Golf Club Vs Tagaytay Highlands Ees Union (D)Angelic ArcherNo ratings yet

- AFP Mutual Benefit Association Inc. vs. CADocument6 pagesAFP Mutual Benefit Association Inc. vs. CALim JacquelineNo ratings yet

- Vallido Vs PonoDocument3 pagesVallido Vs PonoNikki Joanne Armecin LimNo ratings yet

- Benguet Electric Coop Vs Ferrer-CallejaDocument2 pagesBenguet Electric Coop Vs Ferrer-CallejaAngelic ArcherNo ratings yet

- RUBY v. CADocument4 pagesRUBY v. CAchappy_leigh118No ratings yet

- Pepsi Cola Distibutor Phils V Galang September 24, 1991Document1 pagePepsi Cola Distibutor Phils V Galang September 24, 1991Cazzandhra BullecerNo ratings yet

- Holy Cross of Davao College Vs KAMAPIDocument2 pagesHoly Cross of Davao College Vs KAMAPIfranzadonNo ratings yet

- 06 Feliciano v. CoaDocument3 pages06 Feliciano v. CoaIsabella Marie Lumauig NaguiatNo ratings yet

- Bilflex Phil. Inc. Labor Union Et Al. V. Filflex Industrial and Manufacturing Corporation and Bilflex (Phils.), Inc. 511 SCRA 247 (2006), THIRD DIVISION (Carpio Morales, J.)Document1 pageBilflex Phil. Inc. Labor Union Et Al. V. Filflex Industrial and Manufacturing Corporation and Bilflex (Phils.), Inc. 511 SCRA 247 (2006), THIRD DIVISION (Carpio Morales, J.)piptipaybNo ratings yet

- Toyota Motors Philippines vs. Toyota Motors Philippines Labor Union (G.R. No. 121084)Document5 pagesToyota Motors Philippines vs. Toyota Motors Philippines Labor Union (G.R. No. 121084)Ryan LeocarioNo ratings yet

- Halley Vs PrintwellDocument2 pagesHalley Vs Printwellkaira marie carlos100% (1)

- St. Martin Funeral Homes vs. National Labor Relations CommissionDocument2 pagesSt. Martin Funeral Homes vs. National Labor Relations CommissionCali Ey100% (1)

- Aldersgate v. GauuanDocument1 pageAldersgate v. GauuanStef Turiano PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Indophil Union V Calica - DolinaDocument3 pagesIndophil Union V Calica - DolinaPAMELA DOLINANo ratings yet

- Labor - DO 126-13Document14 pagesLabor - DO 126-13Noel Cagigas FelongcoNo ratings yet

- Fourth Batch - Verceles vs. Blr-DoleDocument1 pageFourth Batch - Verceles vs. Blr-DoleRaquel DoqueniaNo ratings yet

- Paz Vs New International Environmental Universality Inc. 756 SCRA 284Document5 pagesPaz Vs New International Environmental Universality Inc. 756 SCRA 284Claudia LapazNo ratings yet

- Ust Vs Samahang Manggagawa NG UstDocument1 pageUst Vs Samahang Manggagawa NG UstwhatrichNo ratings yet

- Answer: Republic of The Philippines Regional Tial CourtDocument5 pagesAnswer: Republic of The Philippines Regional Tial CourtVicco G . PiodosNo ratings yet

- SMC vs. KhanDocument19 pagesSMC vs. KhanGuiller MagsumbolNo ratings yet

- Valdez vs. NLRCDocument5 pagesValdez vs. NLRCMigz DimayacyacNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction Class Digest Update v.3Document41 pagesJurisdiction Class Digest Update v.3Raymarc Elizer AsuncionNo ratings yet

- 1) Mariño vs. GamillaDocument2 pages1) Mariño vs. GamillaMRNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Kawashima TextileDocument2 pagesRepublic v. Kawashima TextileRonnel DeinlaNo ratings yet

- Mainland vs. MovillaDocument6 pagesMainland vs. MovillaKeith BalbinNo ratings yet

- Philippine Associated Smelting and Refining Corp. Vs Pablito LimDocument6 pagesPhilippine Associated Smelting and Refining Corp. Vs Pablito LimOlan Dave LachicaNo ratings yet

- 191 Liberty CMWU Vs Liberty Cotton MillsDocument2 pages191 Liberty CMWU Vs Liberty Cotton Millsjovani emaNo ratings yet

- Labor Law DigestDocument2 pagesLabor Law DigestnorzeNo ratings yet

- Bernales To Subic WaterDocument5 pagesBernales To Subic WaterKatherine NovelaNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument22 pagesCase DigestsStephen John Sison SantosNo ratings yet

- Tan Vs SycipDocument3 pagesTan Vs SycipRaymart SalamidaNo ratings yet

- 204-Univliver Phils., Inc. v. Rivera G.R. No. 201701 June 3, 2013Document7 pages204-Univliver Phils., Inc. v. Rivera G.R. No. 201701 June 3, 2013Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- St. Michael School of Cavite Inc. v. MasaitoDocument10 pagesSt. Michael School of Cavite Inc. v. Masaitojuju_batugalNo ratings yet

- VASSAR INDUSTRIES EMPLOYEES UNION VIEU vs. ESTRELLADocument1 pageVASSAR INDUSTRIES EMPLOYEES UNION VIEU vs. ESTRELLABandar TingaoNo ratings yet

- Sales Digest OdtDocument10 pagesSales Digest OdtJamie VodNo ratings yet

- Reynaldo Lozano v. Hon. Eliezer de Los SantosDocument2 pagesReynaldo Lozano v. Hon. Eliezer de Los SantosbearzhugNo ratings yet

- Maraguinot Vs NLRCDocument19 pagesMaraguinot Vs NLRCPiaNo ratings yet

- SMCEU v. SM Packaging Products Employees Union-PDMPDocument5 pagesSMCEU v. SM Packaging Products Employees Union-PDMPjrvyeeNo ratings yet

- Jacob Vs Puno, G.R. Nos. L-61554-55Document3 pagesJacob Vs Puno, G.R. Nos. L-61554-55Anonymous o9q5eawTNo ratings yet

- Stegner V StegnerDocument3 pagesStegner V StegnerLizzette Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- Augusta Trust Co. v. Augusta, Et Al.Document3 pagesAugusta Trust Co. v. Augusta, Et Al.Kevin HernandezNo ratings yet

- Reyes Vs CA DigestDocument2 pagesReyes Vs CA DigestAbdul-Hayya DitongcopunNo ratings yet

- EDI-Staffbuilders International, Inc. Expertise Search InternationalDocument4 pagesEDI-Staffbuilders International, Inc. Expertise Search InternationalGerard Relucio OroNo ratings yet

- United Seamen's Union of The Philippines Vs Davao Shipowners AssocDocument4 pagesUnited Seamen's Union of The Philippines Vs Davao Shipowners AssocJustin Andre SiguanNo ratings yet

- Insular Drug V PNB - GR 38816 - Nov 3 1933Document2 pagesInsular Drug V PNB - GR 38816 - Nov 3 1933Jeremiah ReynaldoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-38258Document14 pagesG.R. No. L-38258Maria Celiña PerezNo ratings yet

- Sca Hygiene Products Corporation Employees AssociaDocument2 pagesSca Hygiene Products Corporation Employees AssociaLeslie LernerNo ratings yet

- Property Reviewer - EasementsDocument11 pagesProperty Reviewer - EasementsPamela ParceNo ratings yet

- CORPODocument15 pagesCORPOJanine Kae UrsulumNo ratings yet

- Case 3 - ManliguezDocument4 pagesCase 3 - ManliguezCharmaigne LaoNo ratings yet

- Allied Free Workers Vs Compania MaritimaDocument4 pagesAllied Free Workers Vs Compania Maritimatin tinNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations - Labor Organization-Union-Members Relations-Union Affiliation (Pages 23-25)Document53 pagesLabor Relations - Labor Organization-Union-Members Relations-Union Affiliation (Pages 23-25)Francis De CastroNo ratings yet

- Pinlac v. CADocument1 pagePinlac v. CAReymart-Vin MagulianoNo ratings yet

- Progressive Development VS Laguesma SMC Packing VS Mandaue Packing Products PlantsDocument2 pagesProgressive Development VS Laguesma SMC Packing VS Mandaue Packing Products PlantsthedoodlbotNo ratings yet

- Vicmar v. ElarcosaDocument1 pageVicmar v. ElarcosaNN DDLNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations CasesDocument30 pagesLabor Relations CasesEnrryson SebastianNo ratings yet

- Ulp-Cert. Elect CasesDocument176 pagesUlp-Cert. Elect CasesVerdeth Marie WaganNo ratings yet

- Carino Vs NLRCDocument9 pagesCarino Vs NLRCJana Felice Paler GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Carino v. NLRCDocument3 pagesCarino v. NLRCKaren Joy MasapolNo ratings yet

- People V AlidoDocument6 pagesPeople V AlidoBreth1979No ratings yet

- Bernardo vs. NLRCDocument6 pagesBernardo vs. NLRCBreth1979No ratings yet

- Holiday Inn V NLRCDocument3 pagesHoliday Inn V NLRCBreth1979100% (1)

- Filamer Vs IACDocument3 pagesFilamer Vs IACBreth1979No ratings yet

- Jarantilla Vs CADocument5 pagesJarantilla Vs CABreth1979No ratings yet

- Pastor Vs CADocument8 pagesPastor Vs CABreth1979No ratings yet

- Fernandez Vs DimagibaDocument3 pagesFernandez Vs DimagibaBreth1979No ratings yet

- Cuenco Vs CADocument9 pagesCuenco Vs CABreth1979No ratings yet

- Regino Vs Pangasinan CollegesDocument5 pagesRegino Vs Pangasinan CollegesBreth1979No ratings yet

- de La Cruz v. Judge BersamiraDocument10 pagesde La Cruz v. Judge BersamiraBreth1979No ratings yet

- Kiok Loy Vs NLRC GR L-54334Document3 pagesKiok Loy Vs NLRC GR L-54334Breth1979No ratings yet

- Amabe Vs Asian Construction Et Al GR 183233Document9 pagesAmabe Vs Asian Construction Et Al GR 183233Breth1979No ratings yet

- Christian Vs NLRC GR 79106Document3 pagesChristian Vs NLRC GR 79106Breth1979No ratings yet

- Univ Sto Tomas Vs Samahang Manggagawa NG UST GR 169940Document11 pagesUniv Sto Tomas Vs Samahang Manggagawa NG UST GR 169940Breth1979No ratings yet

- Ibm Vs NLRC 198 Scra 586Document3 pagesIbm Vs NLRC 198 Scra 586Breth1979No ratings yet

- Associated Labor Union Vs Ferrer-Calleja GR No L-48367Document4 pagesAssociated Labor Union Vs Ferrer-Calleja GR No L-48367Breth1979No ratings yet

- KMP Vs Trajano GR No L62306Document3 pagesKMP Vs Trajano GR No L62306Breth1979No ratings yet

- Caste SystemsDocument17 pagesCaste SystemsNithin NairNo ratings yet

- Newspaper Headlines Useful LanguageDocument3 pagesNewspaper Headlines Useful LanguagepoukalosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 16Document2 pagesLesson 16tigo143No ratings yet

- Salas V Jarencio - DigestDocument1 pageSalas V Jarencio - DigestSol RoblesNo ratings yet

- Samuel Gachago ProfileDocument7 pagesSamuel Gachago ProfileJohn NdasabaNo ratings yet

- Civ Rev Digest Republic v. SantosDocument2 pagesCiv Rev Digest Republic v. SantosCharmila SiplonNo ratings yet

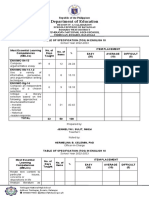

- Table of Specification-ThirdDocument2 pagesTable of Specification-ThirdJennelyn SulitNo ratings yet

- The Journal of African History: L'heure Des Indépendances. Par Charles-RobertDocument4 pagesThe Journal of African History: L'heure Des Indépendances. Par Charles-RobertIssa DiopNo ratings yet

- The Dispute Between Philippines and China Concerning Territorial Claims in The West Philippine SeaDocument36 pagesThe Dispute Between Philippines and China Concerning Territorial Claims in The West Philippine SeaFaye Cience Bohol100% (1)

- FURLONG, PATRICK J. - Fascism, The Third Reich and Afrikaner Nationalism - An Assessment of The HDocument16 pagesFURLONG, PATRICK J. - Fascism, The Third Reich and Afrikaner Nationalism - An Assessment of The Huchanski_t100% (1)

- XXX XXX XXX "XVIII. Urea Formaldehyde For The Manufacture of Plywood and Hardboard When Imported by and For The Exclusive Use of End-Users."Document3 pagesXXX XXX XXX "XVIII. Urea Formaldehyde For The Manufacture of Plywood and Hardboard When Imported by and For The Exclusive Use of End-Users."mercy rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Disguise For CoverDocument4 pagesDisguise For CoverMfayyadhNo ratings yet

- Folk Fest Ready To FlyDocument2 pagesFolk Fest Ready To FlypegspirateNo ratings yet

- Bibliografie Proiect de Pe NetDocument6 pagesBibliografie Proiect de Pe Netiryna1989No ratings yet

- Fatwa For ASB and ASNDocument13 pagesFatwa For ASB and ASNNurhani Abd MuisNo ratings yet

- FMLN, Hegemony in The Interior of The Salvadoran Revolution. The ERP in Northern Morazán (JLAA Vol.4)Document44 pagesFMLN, Hegemony in The Interior of The Salvadoran Revolution. The ERP in Northern Morazán (JLAA Vol.4)EDisPALNo ratings yet

- Emerging Principles of International Competition LawDocument466 pagesEmerging Principles of International Competition LawYujia JinNo ratings yet

- NAMAWU v. NLRC, 118 SCRA 637 (G.R. No. L - 59596, Nov. 19, 1982)Document7 pagesNAMAWU v. NLRC, 118 SCRA 637 (G.R. No. L - 59596, Nov. 19, 1982)Karnisha ApocalypsoNo ratings yet

- War Peace Islam PDFDocument552 pagesWar Peace Islam PDFJohn of New York100% (1)

- Final Question and Answer For MPW Malaysian StudiesDocument2 pagesFinal Question and Answer For MPW Malaysian Studiesfarhanialihoneybunny50% (2)

- Approaches To The Study of GlobalizationDocument4 pagesApproaches To The Study of GlobalizationRosa PalenciaNo ratings yet

- Agura v. Serfino SR., 204 SCRA 569 (1991)Document1 pageAgura v. Serfino SR., 204 SCRA 569 (1991)Lovely Grace HechanovaNo ratings yet

- 3 - Forms of The GovernmentDocument4 pages3 - Forms of The GovernmentAhsan LavaNo ratings yet

- Public Charge Comment - Daniel Garza, The LIBRE InitiativeDocument2 pagesPublic Charge Comment - Daniel Garza, The LIBRE InitiativeAmericansForProsperityNo ratings yet

- DC-5 - Lesson 3Document14 pagesDC-5 - Lesson 3Amit Kr GodaraNo ratings yet

- CSWDocument4 pagesCSWEMS Region2No ratings yet

- Chapter 33 History Outline (American Pageant 13th Edition)Document8 pagesChapter 33 History Outline (American Pageant 13th Edition)djhindu1100% (3)

- Baghlan ProvinceDocument4 pagesBaghlan ProvinceZubair YousufzaiNo ratings yet

- Bali Bomber To Face Firing Squad - Advanced PDFDocument4 pagesBali Bomber To Face Firing Squad - Advanced PDFhahahapsuNo ratings yet

- 31 Shubham Dangat Mind Mapping 30.07.2021Document1 page31 Shubham Dangat Mind Mapping 30.07.2021Anand VirwaniNo ratings yet