Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Globalisation, Higher Education and Social Equity in Kerala

Uploaded by

Kannan C Chandran0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

128 views201 pagesGlobalisation and Higher Education in Kerala- Access- Equity and Quality

Original Title

Globalisation and Higher Education in Kerala- Access- Equity and Quality

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentGlobalisation and Higher Education in Kerala- Access- Equity and Quality

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

128 views201 pagesGlobalisation, Higher Education and Social Equity in Kerala

Uploaded by

Kannan C ChandranGlobalisation and Higher Education in Kerala- Access- Equity and Quality

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 201

GLOBALISATION AND HIGHER EDUCATION IN KERALA: ACCESS,

EQUITY AND QUALITY

Report of a Study sponsored by the Sir Ratan Tata Trust

Praveena Kodoth

Centre for Development Studies

Trivandrum 695011

Kerala

Acknowledgement

It has been possible to carry out this study only because of the support received from

several colleges in the state, which responded to our request for information. In

particular, I am grateful to the seven colleges, where we conducted surveys and did more

intensive fieldwork. I am also indebted to the representatives of managements,

Principals, teachers and students who were willing to give us their precious time and their

valuable input. There are many people who contributed so warmly to my understanding

of the area and it pains me not to mention them but I do so in order to protect the

identities of the colleges and the persons concerned.

I would also like to thank Dr D. D. Namboodiri and Professor K N Panikkar for

discussions at the initial stages of the study. Rakhe and Kochurani for so kindly helping

to locate researchers.

Anjana MV, Alice Sebastian, Feba Elizabeth Jacob, Sujith P. K. and Loshita Prabhakaran

conducted the field work in five of the six colleges taken up for in depth study and

transcribing the interviews and discussions. Additionally, Feba also took responsibility

to get us the completed questionnaires from some of the colleges in central Travancore.

Maya S carried out the survey in one college. Mr Unnikrishnan, Mr Padmanabhan

ensured that we received filled in questionnaires from colleges in the northern region,

whereas Mr Anils efforts are responsible for the large number of colleges that returned

questionnaires in the southern region. Vinod S. managed the difficult task of cross

checking the data received from colleges, calling them up wherever there were doubts

and also entered the data. I am grateful to all of them.

The long and laborious task of data entry and analysis of the survey data received from

seven colleges was undertaken by Anjana M V with assistance from Sudha. Sreelatha R

assisted in the process of analysis of data and preparation of tables for the report. At

various points during the data entry and analysis we received help from Braja Bandhu

Swain and Anirban Kundu. I would like to thank all of them. I am immensely grateful to

Anjana for overseeing a process, complicated by the need to standardize the

questionnaires, with care and commitment.

At the Centre for Development studies, I would like to thank the Director for his interest

and encouragement. U. S. Mishra, V Santhankumar, V.J. Varghese have been supportive

throughout the study in terms of commenting on the questionnaires and providing advice

on research techniques and data analysis. I am indebted to them. The Registrar, Mr

Soman Nair was always willing to help and I am very grateful to him and to Mr Suresh at

the accounts for their support. I am also happy to thank the office staff for always being

ready to help.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 2 Interpreting Access, Probing Equity

Chapter 3 Framing Quality in Higher Education: Standard Indicators, Reported

Problems and Teacher Availability

Chapter 4 The Challenge of Providing Quality Higher Education: Access to Basic

Facilities

Chapter 5 Negotiating Quality in Higher Education: Politics and College

Environment

Chapter 6 Conclusion

Executive Summary

The failure of the publicly funded segment of arts and science colleges to expand

has restricted the access of students, particularly from the more marginalized

sections of society, to higher education.

Barriers to access to the publicly funded segment of undergraduate arts and

science education are relatively greater in the northern parts of the state, where the

majority of students continue to rely on parallel colleges.

The pressure on the publicly funded segment to expand is more apparent in

southern Kerala in the relatively greater resort to marginal increases in colleges in

the region.

There is a marked shortage of enrolment in specific basic science courses in the

central Travancore region, in an indication that the preference for professional and

technical education and job oriented self-financing courses is better honed in the

region.

There is no significant dearth of applicants for the humanities and social science

courses in any of the university regions and there is a marked preference among

students for courses in commerce, economics and business in all regions.

At the state level, the proportion of SC / ST students in arts and science colleges

is far below the reservation quota and the social and economic profile of students

currently in select arts and science colleges indicate that those from

underprivileged backgrounds face barriers in gaining access.

Colleges are unable to retain students from the most marginalized groups on

account of cultural barriers.

The domination of girls over boys in arts and science colleges is on account of a

combination of the desire of girls to find employment and the lower importance

attached socially to girls employment.

The college environment and the quality of education offered by colleges are

influenced by the nature of the management, which may be of three kinds:

excessive, indifferent and measured.

2

Excessive management is found usually among private aided colleges and is

marked by a suspicion and lack of trust leading to lack of incentives for teachers

to perform and restrictions on students against the use of even basic facilities.

Excessive management usually leads to prohibition of politics unless the college

does not have social support in the locality to withstand the resistance from

students.

The Government colleges and a section of privately aided colleges suffer from

indifferent management which fosters weak administrations, shapes poor

incentives to perform and leads to little systematic effort to raise additional funds.

Indifferent management makes way for indiscipline among students, could affect

transparency and accountability in vital aspects of the education process including

admissions and examinations, enable interference by political parties and could

result in a coercive environment.

A few of the private aided colleges benefit from measured managements which

foster strong administration, provide incentives for teachers to perform and give

students access to good basic and student support facilities. They are marked by

efforts to raise additional funds from public and private sources.

The Government colleges are less responsive to external assessment, offer little

performance incentives for teachers and students, make little effort to get newer

employment oriented courses and thus are less competitive than private aided

colleges.

The private aided colleges are weighed down by a framework of patronage

dispensation, which compromises the standard criteria (merit and reservation) for

admission of students and recruitment of teachers.

The single biggest constraint faced by arts and science colleges is the scarcity of

teachers, a problem that is heightened in the remotely located government

colleges including those more generally in the far north and north east of the state,

which are unable to retain teachers allotted to them.

The less powerful aided colleges are also affected more than others by the scarcity

of teachers as they are less able to challenge Government restrictions against

recruitment by going to court.

3

The remotely located Government colleges have poor or inadequate physical

infrastructure but they are well equipped with IT facilities.

Students in many colleges experience the denial of political space through capture

of politics by student organizations or through prohibition of politics by the

college management.

Even where political mobilization is permitted and is the basis of elections to the

students council, political space may be compromised due to the subordination of

student organizations to the vested interests of political parties.

Depending upon who wields power in a college, the administration or the student

organization mobilizes gender to discipline women and to legitimizes intensive

moral policing.

While there is no effort to mobilize on the basis of identity as Dalit, the dominant

discourse in colleges dismisses caste discrimination as irrelevant.

Teachers trade unions too are perceived to be too closely associated with political

parties to be able to respond critically to the policies of governments and are seen

to compromise on the academic interests of teachers.

Political interference is perceived to have compromised the standards of teaching

in colleges by breeding irresponsibility among teachers who are not self

motivated.

The ongoing reforms package is perceived widely as useful but also as being

implemented in politically motivated way. Thus, the private aided colleges see

the cluster college scheme as a means to allow student organizations from outside

to enter their campus and disturb peace.

4

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Since the 1990s, higher education in Kerala has been subject to significant policy shifts,

which hold long-term implications for the general arts and science segment. At least

three sets of policy moves in the recent past have altered or hold the potential to alter

significantly the context of general arts and science education in the state. First, the

opening of the doors to self-financing colleges, somewhat ambiguously in the 1990s but

with full force since 2000, initiated full fledged private participation in the sector whereas

previously private participation had been publicly funded through the private aided

colleges, which receive public funds but are managed by private establishments mostly of

the nature of voluntary or charitable trusts. As general arts and science education is

frequently perceived (whether or not it actually is) as a residual option of those who do

not qualify for professional courses or those who are simply not adequately well

informed to take advantage of them, the exponential increase in private self financing

professional colleges since 2000 is also likely to affect it, by boosting aspirations for

professional and technical education and driving students away from general arts and

science. Second, from 1998 onwards the pre degree courses were delinked in a phased

manner from arts and science colleges and brought under the higher secondary schools as

plus two courses, a process that was completed in 2001. The delinking of the pre degree

courses led to some amount of disarray in logistical arrangements especially with respect

to the existing strength of teachers and in 2004 the government imposed a ban on new

appointments of teachers in private aided colleges, which was lifted only in 2008 (G.O.

(MS) No 63/2008/H.Edn). This seems to have contributed to the scarcity of teachers in

many private aided colleges. Less perceptibly, it also narrowed the social class base of

arts and science colleges as the pre degree students were drawn from a more

heterogeneous class base leading to a depletion of the interests of the relatively more

powerful middle class in arts and science colleges. Third, very recently the Kerala State

Higher Education Council (KSHEC) has initiated reforms in undergraduate arts and

science education, which envisages a radical overhauling of the existing structure and

practices. The KSHEC, which was set up in March 2007, proposed several moves to

5

generate the informational base for restructuring higher education.

1

Kerala university,

the only university in the state that has not implemented the reforms is scheduled to do so

in 2010. While these reforms have the potential to effect significant changes, they are

likely to take time to take root and it would be premature to comment on the reforms at

this point except by way of preparations being made and the fears expressed by

stakeholders in the process.

This study will examines some of the significant constraints facing the undergraduate arts

and science segment of higher education in the context of crucial ongoing changes. The

study was envisaged as an effort to map some of the basic dimensions of constraints and

possibility and hence is an exploratory one. The focus of the study is on undergraduate

arts and science education provided by the Government and the private aided colleges.

Currently, the arts and science colleges are differentiated according to management into

Government, private aided and private unaided segments.

2

We have not taken up the self

financing sector for study here for a number of reasons. Importantly, the colleges in this

segment offer a very narrow range of courses designed to suit the job market. A

preliminary sampling of information available on the websites of the universities suggests

that a major section of colleges in this segment have fewer than three courses, several of

them offering only two, and the most frequently offered courses are electronics, computer

science/applications, business management/administration and what are perceived as job

oriented applied science courses such as biotechnology. Given their recent vintage, their

narrow range of courses and exponential growth since 2000 (few were functioning in

1995), these institutions seem to present a wholly different genre and may well merit a

separate inquiry.

1

The U R Ananthamurthy committee drafted a higher education policy for the state and a committee has

submitted a report on restructuring undergraduate education. The key issue here was of quality and the

report of the committee drew up a road map for reform, which includes importantly, a) reform of structure

i.e., a shift from the annual pattern to a modified course credit semester system and b) reform of content,

i.e., curriculum and pedagogy. The current road map envisages the introduction of a) limited internal

assessment for the upcoming batch of students and b) comprehensive reform for the 2009 batch. Among

the other issues that the council has prioritized, which directly impinge on access, quality and equity are the

promotion of the concept of cluster colleges and setting up of higher education scholarships.

2

The private aided colleges are publicly funded. Under a direct payment agreement with private aided

colleges, the government pays teachers. These colleges also receive development funds from state

agencies, both at the Central and State levels.

6

1.2 Overview of Issues

The recent ferment in higher education may be located within the context of changes in

political economy that gained a new coherence in the 1990s with what may be referred to

as globalization and raised rather new challenges. They include the relevance of higher

education as the basis of new employment opportunities in an economy that was fast

opening up to global forces. In the specific context of Kerala, there were the demands of

the rapidly growing service sector, the inability relative to other south Indian states and

cities to tap opportunities in ICT and the need to retain migrant jobs, whose social-skill

profile was changing implicating the need for greater investment in higher education.

3

As against this, Keralas well publicized achievements in education pertained largely to

primary and secondary school education. It has been pointed out that on higher

education, Kerala fell behind several Indian states on several dimensions of access but

especially on the availability of educational opportunities within the state relative to

population and the number of students enrolled in these institutions (Tilak 2001). In the

past five years there has been a significant rise in the pass percentages at the SSLC and

higher secondary levels, adding to the numbers of aspirants for higher education.

4

It is a

measure of the intensity of the problem that despite differences, voices from across the

political divide in the state agree that there is a dearth of higher education opportunities in

the publicly funded segment.

5

Even prior to the advent of the self financing colleges, the

scarcity of colleges was met to some extent by the parallel colleges, which catered to

privately registered students (Nair and Ajit cited in Tilak 2001). Thus, there is a degree

of awareness of an acute problem of access. The quality of higher education and issues

of equity in Kerala too have come in for adverse comment. It is alleged that the rapid

increase in colleges in the self financing segment portends a new low in quality of

3

It is of concern in the state that the demand profile of labour for the Gulf and other states is changing in

ways that require more skilled personnel.

4

The pass percentage of SSLC students climbed from 62 percent in 2005 to 94 per cent in 2008 and higher

secondary students climbed from 61 per cent in 2006 to 73 per cent in 2008.

5

It was on these grounds that the UDF justified the opening up of higher education to self financing private

participation. Drawing attention to the mushrooming of the private sector institutions Prabhat Patnaik,

Vice Chairperson of the State Planning Board under the current LDF government notes that it, basically

means that the demand for these institutions has outstripped what the public educational facilities could

take care of (The Hindu, April 15, 2008).

7

education and in this context, Vice Chairperson of the State Planning Board, Prabhat

Patnaik is at pains to note that, [u]nfortunately, even in the public education system, the

quality has gone down greatly (Patnaik, The Hindu, April 15, 2008). Significantly,

there has been no study of the private self financing segment of higher education which

has been in existence since the 1990s. Thus, adverse comments regarding the quality of

education they supply are derived from the putative motivations for entry into higher

education i.e., profit making (see Tilak 2001, Patnaik, 2008). Studies on the parallel

colleges, which cater to privately registered students, do indicate poor quality of

education (Sivasankaran and Krishnan 1999 in Tilak 2001). Poor quality is implicated

also in comments in the public domain on the limited expansion of the IT industry in

Kerala. For instance, it has been remarked that Keralas graduates are unemployable in

IT related jobs because of their poor English language skills.

6

Equity concerns are

implicated in the fees charged in higher education as well as the dearth of scholarships.

The impression that higher education is free in Kerala or involves very low fees has been

questioned. A study in 1992 showed that students in Government colleges spent up to Rs

4000 per annum per head towards various costs, whereas in private colleges this was

about Rs 5000, which was more than the per capita state domestic product of the state at

the time (Salim 1995).

7

Tilak (2001) also shows that scholarships receive a negligible

share of government finances for education and had declined from 0.7 per cent of total

higher education budget in 1990 91 to 0.2 per cent in 1996 97. Notably, in the past

year the KSHEC set up a scholarship fund with contributions from Government and

private donations.

An emerging literature since the 1990s, has dealt with higher education in Kerala in the

context of macro economic policy shifts or what may be designated broadly as

globalization. Much of this literature looks at the economics of higher education framed

in the context of macro resource constraints but ranging from issues of financing and

6

It [Kerala] should stop producing unemployable graduates and learn to impart the kinds of skills modern

industry and business require. It should realise that its education system is obsolete and unsuited for the

Knowledge Era, P V Indiresan, the Hindu Business line, Oct 30, 2005

7

Costs computed by Salim included academic - pre admission, college fees, private tuition, books,

stationery, study tours etc. incidental hostel, clothing, subscriptions, travel, entertainment, donations

etc.

8

costs to entry barriers to professional and technical education (Salim, 1995, 1997, 2004,

Devasia 2008, Mathew 1991, GoK, 2006). A recent essay addresses higher education as

a key site of the constitution of a gendered and generational political public, which form

axes of exclusion/inclusion. It questions the dominant frames of the debate on higher

education in terms of state/public and market/private (Luckose 2005). While these are no

doubt important concerns, their implications for the sector are limited by the absence of a

more general mapping of the site. Recent work has noted the absence of research on

higher education leading to confusion regarding basic issues like its reach (GoK, 2006,

http://www.kshec.kerala.gov.in/). For its part the HDR, 2005 notes that Kerala a) has not

seen adequate quantitative expansion in higher education i.e., in the general arts and

science segment and b) trails five major states (Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu,

Gujarat and West Bengal) in the growth of graduates as a percentage of the population

above seven years (GoK, 2006: 92). However, the HDR too focused on technical

education, as the segment that was vital to the development vision of the state, especially

through the generation of future employment potential.

It may be noted that policy changes are intermeshed in the competitive politics of the

state, with the two major political alliances, the Left Democratic Front (LDF) and the

United Democratic Front (UDF) vying with each other for stake in the sector. The

KSHEC, set up under the current LDF government, has prioritized reforms in

undergraduate arts and science education and three out of four universities initiated the

shift to grading as the mode of evaluation and to a choice based course credit semester

system in 2009, based on a reformulated curriculum. The UDF and its allied bodies

among teachers and students have criticized the reforms initiated by it with being

politically motivated and lacking transparency alleging that the KSHEC was taking over

the functions of the education department. The UDF government, which opened the

doors to self financing colleges tentatively in the 1990s and with more vigor since 2001

maintains that it was a measure to address the growing demand. The LDF has been

highly critical of the move, claiming that it has turned education into a profiteering

concern at huge cost to equity and quality.

9

Not infrequently, this political ambience percolates into the day to day working of the

arts and science colleges, where broader political stakes are expressed in deeply

entrenched divisions among students and teachers associations affiliated to one or other

political parties. At one extreme, students associations are known to vie for hegemony

but in seeking to establish hegemony, associations resort to brute force to wipe out any

sign of counter or alternative mobilization. While the Students Federation of India,

affiliated to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) has the relatively wider and stronger

network of college-level associations in the state, in a few colleges a single students

association (the SFI or the ABVP) maintains a monopoly on political activity through

coercive means. At the other extreme, many private aided colleges, especially those

managed by Catholic associations have been more successful than others in eliminating

the space for politics altogether by banning political mobilization, association and activity

on their campuses, a step that has received support from the Kerala High Court in a

judgment in 2003 (Sojan Francis vs M G University, 26/5/2003,

http://indiankanoon.org/doc/1345236).

1.3. Comparative Overview of Higher Education in Kerala

The gross enrolment ratio (GER), a widely used indicator of access to higher education is

also used to denote the educational advancement of a region.

8

It is the ratio of persons

enrolled in higher educational institutions regardless of age divided by the number of

persons in the relevant age group. The GER for Kerala has tended to suggest different

trends depending on the source of data used to compute it (table 1.33). Analysis of data

compiled and published by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, the Selected

Education Statistics shows that Kerala has tended to fall below the all India average in

terms of enrolment in higher education institutions within the state. This should be a

matter for concern given that Kerala has near total enrolment at the primary and upper

primary school levels and significantly higher levels than all India at the secondary

school level (Tilak, 2001). However, it is recognized that the SES underestimates

enrolment owing to the lack of reporting by the state education departments to the

8

For the developing countries in 2001-02 the GER was only 11.3 %, half of the world average at 23.2 %

(average for developed countries being 54.6 %) (Duraisamy, 2008: 32).

10

MHRD in some years leading to the use of extrapolations as well as possibly some

amount of underreporting owing to the uneven data gathered by the states (Sinha and

Srivastava, 2008, Duraisamy 2008). According to Duraisamy (2008: 33) a major source

of underestimation is because the SES does not capture enrolment in unrecognized

institutions. In the context of Kerala, unaided colleges, which were first established in

the 1990s, have grown steadily since 2000, and while they are recognized educational

institutions, enrolment in them has not been reported. This is evident in from the number

of arts and science colleges reported in the SES, which accounts only for the colleges in

the Government and aided sectors in the state (see table 1.41). Further, the parallel

colleges, which have persisted over the years as an avenue of higher education for

students who are privately registered, are unrecognized and hence not included in the

SES data. It is reported that 70 per cent of undergraduate registrations under Calicut

university are private and only five per cent of these students go through the distance

education mode (Naha, The Hindu, April 27, 2010).

9

Exercises comparing the GER at the all India level from SES with that from NSS and

Census for the 18 23 age group show that the NSS and Census report significantly

higher ratios (Sinha and Srivastava, 2008: 115). In the case of Kerala, however, not only

does the GER increase significantly when we turn to the NSS or Census but also contrary

to the trend in the SES, the GER in Kerala is significantly ahead of the all India average

(table 1.23). Further, table 1.33 also shows that the difference between GERs from

different sources is significantly higher for Kerala than for all India. It is recognized that

as against the SES, the NSS and Census are likely to overestimate GER as they might

include enrolment in diploma or training programmes (Duraisamy, 2008: 33). Keralas

significantly higher GERs from the NSS or Census could involve, apart from

underestimation in the SES, owing to enrolment in parallel colleges and unaided colleges

which is considerable as we have seen above, also some movement of students to

institutions outside the state for higher education (the SES reports only the number of

9

This was highlighted during the efforts by Calicut university to negotiate with the cooperative and parallel

colleges in region to bring privately registered students too under the Choice based Course Credit Semester

System (Naha, The Hindu, April 27, 2010).

11

students enrolled in institutions within as state).

10

While we do not have data on this, it is

the general impression that a large numbers of students from Kerala go to other state for

higher studies in specialized areas such as nursing but also in the general arts and science

segments. In the survey we conducted in seven colleges in the state (discussed in later

chapters) 25 per cent of undergraduate students said they would like to go outside the

state for higher studies. The movement of students out of the state may be an indication

of the dearth of suitable higher education opportunities in the state, as well as a dearth of

opportunities in the publicly funded segment. In suitable higher educational

opportunities, we include not only specific courses, which may not be available in the

state but also the standards of education in the state and the general character of

campuses in the state, marked by political interference and violence, which may induce

students to move out.

Table 1.31 shows a significant increase in the number of colleges in the state since 1986-

87. Notably, the growth rate of colleges in the state between 2000-01 and 2006-07 is

close to that between 1986-87 and 2000-01 (see table 1.32). If we take into account the

colleges in the unaided sector the growth rate would be still higher. Further, while the

growth of colleges between 1986-87 and 2000-01 is significantly higher for all India than

for Kerala, it is only slightly higher for all India between 2000-01 and 2006-07. Thus, in

the first decade of 2000 there has been considerable increase in colleges providing higher

education in Kerala but as table 1.31 shows this increase is not reflected in the arts and

science colleges. However, the data on the professional colleges includes the self

financing colleges as is evident from a comparison with data published by the state

government annually in the Economic reviews.

11

10

The variation in table 1.1 between SES, NSS and Census ratios is influenced also by the differences in

age groups of population, which is used as the denominator. However, the difference is by over 10

percentage points, which cannot be accounted for by a small difference in the age base of the population

used.

11

Out of 84 engineering colleges in the state in 2008 with a sanctioned intake of 25,492 students, 83 per

cent are in the self-financing segment (sanctioned intake of 21,240). About 65 per cent of all medical

opportunities are in the self financing segment. The self-financing colleges have grown exponentially since

2000. At the end of the eighth five year plan in 1997 there were only 15 engineering colleges (and only 3

in the self financing segment). This had grown to 84 in 2005 and remains at that level in 2008

(Government of Kerala (ER), 2004, 2005, 2008). The growth in the self financing segment has been much

less in technical education where there are only 9 polytechnics and 5 technical high schools as against 49

12

If the GER in higher education in Kerala has tended be lower than for all India according

to the SES, it is striking that girls in Kerala register significantly higher GERs than boys,

whichever data source is used, while the reverse is true at the all India level (tables 1.24

and 1.35). In table 1.34, at the all India level, the GER for boys is four percentage points

greater than for girls in two of three years shown (2005-06, 2006-07) whereas in Kerala

the GER for girls is more than one percentage point higher than for boys in all the three

years shown. This gendered pattern, where more girls than boys are enrolled in higher

education in Kerala, is seen in the case of SC and ST students as well. Table 1.35 shows

that the GER for girls in Kerala in 1993-94 (using NSS data) is nearly two percentage

points less than for boys but has since then been significantly higher than for boys. For

India, while the GER for boys has remained significantly above that for girls, the

difference in percentage points had declined over the years. At the state level, table 1.36

shows that in recent years girls comprised 75 % or more of enrolment in the M.A., M. Sc

and the B. Ed courses, little over half in the B Com and Open university enrolments and

less than 40 per cent in Engineering and polytechnic enrolment. Thus, engineering and

polytechnic education remain male bastions while medicine and related courses are

dominated by women. In contrast, at the all India level, all streams of higher education

continue to be dominated by men, including teachers education.

Table 1.31: Number of colleges in different segments of higher education in Kerala*

YEARS A&S ENGG + MED + T TR POLY OTHER TOTAL

1986-87 129 6 16 19 NA 19 189

2000-01 186 23 20 19 NA 104 352

2002-03 186 66 40 21 NA 82 395

2004-05 186 66 40 21 56 82 451

2006-07 189 98 125 21 59 82 574

Source: Selected Educational Statistics, 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07, * data is provisional

Engg+: Engineering, Tech and Arch, Med+: Medicine, nursing, pharmacy etc, Others: Law, Management,

MCA/IT, Agriculture etc.

polytechnics in the government and aided segments and 39 government technical high schools

(Government of Kerala (ER), 2007).

13

Table 1.32: Growth rates of Colleges in all segments of higher education in Kerala

YEARS KERALA INDIA

1986-87 to 2000-01 1.86 2.14

1986-87 to 2006-07 3.03 3.52

2000-01 to 2006-07 1.63 1.65

Source: Computed from Selected Educational Statistics

Table 1.33: Gross enrolment ratio in higher education from various sources

Years Kerala India Years Kerala India

SES, (18-24 years) NSS** (18-22 yrs),

1998 99* 3.70 6.00 1993-94 16.70 9.99

2002 03* 7.60 8.97 1999-00 20.80 11.38

2004 05 8.32 9.65 2004-05 24.96 13.59

2005 06 11.57 11.60 Census# (18-23 yrs)

2006 07 11.82 12.39 2001 17.60 12.40

Source: Selected Educational Statistics, 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07; * computed by Tilak (2001); ** NSS

results are from Dubey, 2008, # Census results are from Sinha and Srivastava (2008).

Table 1.34: GER in higher education by sex and social group, (SES, 18-24 years)

KERALA INDIA SOCIAL

GROUP Boys Girls Total Boys Girls Total

2004-05

All 7.04 9.53 8.32 11.11 8.22 9.65

SC 5.95 8.97 7.52 7.81 5.11 6.53

ST 6.24 6.95 6.62 6.10 3.40 4.72

2005-06

All 10.91 12.20 11.57 13.36 9.37 11.60

SC 8.17 12.73 10.54 10.14 6.33 8.32

ST 9.97 13.34 11.78 8.59 4.69 6.61

2006-07

All 11.04 12.56 11.82 14.53 10.02 12.39

SC 8.99 10.42 9.75 11.52 6.96 9.35

ST 9.41 10.31 9.70 9.44 5.51 7.45

Source: Selected Education Statistics, 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07

14

Table 1.35: GER in higher education by sex for India and Kerala (NSS, 18-22 years)

YEARS REGION MALE FEMALE TOTAL

Kerala 17.66 15.85 16.70 1993-94

India 13.09 6.66 9.99

Kerala 17.96 23.42 20.80 1999-00

India 13.57 9.06 11.38

Kerala 21.26 28.51 24.96 2004-05

India 15.56 11.41 13.59

Source: Culled from Dubey (2008)

Table 1.36: Percentage of girls enrolled in higher education courses in Kerala

COURSE 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07

MA 74.98 74.82 80.20

MSc 80.71 77.36 81.98

Mcom 67.11 66.35 71.86

BA 66.48 66.88 66.73

BSc 68.45 69.16 70.15

BCom 53.99 53.39 53.04

Engineering 20.00 37.86 37.86

Med + 57.20 62.46 66.12

B Ed / BT 77.15 80.93 75.90

Open Univ NA 49.30 53.40

Polytechnic 28.96 28.96 28.95

Source: Selected Educational Statistics 2004-05, 2005-06, 2006-07, Med + includes dentistry, pharmacy,

nursing, etc

1.4: Undergraduate Arts and Science Education in Kerala

Colleges in the state are registered under four affiliating universities Kerala university,

Mahatma Gandhi University, Calicut University and Kannur University. Kerala

university affiliates colleges in three southern districts Trivandrum, Kollam and

Allapuzha. MG university covers two districts in south Kerala Pathanamthitta and

15

Kottayam one district in the south east Idukki and one district in central Kerala

Ernakulam. Calicut university continues to have the largest territorial covering the

districts of south Malabar Trissur, Palghat, Malapuram, Kozhikode and Wayanad.

Kannur University was formed only recently from out of Calicut university covers

colleges in Kannur and Kasargod districts in the north and two colleges in Wayanad in

the east were brought under it. There has been a concentration of aided colleges in the

region covered by MG University, which is central Travancore, a Christian belt where

missionary groups and local church organizations has been active in setting up colleges.

The region also has the headquarters of the NSS and a number of colleges under its

management. There are fewer government colleges in this region and a concentration in

the jurisdiction of Calicut university. Until the formation of Kannur University to cover

the colleges in the far north, all colleges in the Malabar region were under Calicut

university and as the region was considered educationally backward, it saw effort in the

years by the state after the state of Kerala was formed to establish more educational

institutions.

Until the surge of self-financing arts and science colleges since 2000, the majority of arts

and science colleges in the state were in the private aided sector. As already mentioned

the private aided colleges receive public funding towards the payment of teachers salaries

as well as development funds. Table 1.41 shows that in 2006 there were only 39 arts and

science colleges run by the Government as against 150 in the private aided sector and 167

self financing colleges. However, several self-financing colleges have failed to survive

as is apparent in a quick decline in numbers to 153 in 2008 (GOK, 2008). A striking

feature of undergraduate arts and science education in Kerala is that the number of

colleges in the public funded sectors (government and the aided colleges) has virtually

stagnated since mid 1990s only three were started since 1996, while, the private

unaided colleges or self financing colleges have grown precisely after the mid 1990s.

There were about 170 colleges in 1990 and sixteen more were started in the following

five years. Since 2000, with the exception of Kerala university, there are more self

financing colleges than colleges in the government or private aided sectors under all

universities in 2000. We have already noted that the focus of the colleges in the self

16

financing sector i.e., the unaided private colleges, is technical and applications oriented

electronics, computer science, business management, micro biology, bio technology are

offered frequently, the odd college offers chemistry, physics, economics, geography,

travel and tourism and fashion and apparel design.

12

While social science subjects, with

the exception of economics, are conspicuous by their absence, a few of these colleges

(mostly Christian or Muslim and/or womens colleges) offer some combination with

English as the main subject (communicative English, functional English, English with

journalism) and home science. The provision of employment-oriented courses reinforces

the view that the return to a liberal arts education is poor, leaving their provision to the

government and aided sectors. Notably, the state-run IHRDs/CASs, also in the self-

financing sector, invariably offer only two courses Bachelor of Science in Electronics

and Computer Science. Another recent feature that is not apparent in table 1.41 is that

there are self financing courses in colleges in the government and aided sectors, for

which public funding is not extended. The colleges are expected to arrange their own

physical and social infrastructure for these courses. Our research shows that several

colleges have self-financing courses running alongside regular ones. The profile of self-

financing courses offered in the regular colleges are similar to those offered in the

unaided private colleges.

For several decades now the inadequacy of the colleges to meet the needs of

undergraduate arts and science education in the state, was addressed, however poorly, by

the provision for private registrations. Catering to this segment, a large number of

unregistered undergraduate teaching institutions, popularly referred to as parallel

colleges, came into being since the 1970s. The parallel colleges, which are distinct from

tutorial colleges / coaching centers addressing students of regular colleges, continue to be

a prominent feature of the states higher education scenario. Since the 1980s there has

been a secular increase in private registrations in all universities and streams of

education. However, since 2002, there has been a moderation in growth and even a

decline in some courses. Universities in the state, with the exception of Calicut

12

This is apparent from the listing of courses offered by each of these colleges under the web sites of the

different universities.

17

university, have witnessed a significant decline in private registrations. Under Calicut

university the pace of increase of private registrations has declined after is rose from

2001 to 2003. It is notable that private registrations for B Com outstrips that for BA

courses in all universities, but also that the decline the former stream has been sharp

except under Calicut university. Notably this has coincided with the rise of the private

self-financing segment.

Private Registrations in Kerala since 2000

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Year

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

r

e

g

i

s

t

r

a

t

i

o

n

s

Kerala U BA

Kerala U B Com

Calicut U BA

Calicut U B Com

MG U BA

MG U B Com

Source: Government of Kerala (ER) various issues

A well recognized feature of the arts and science education sector in Kerala is the

predominance of female over male students. Table 1.36 in the previous section shows

that this is the case across streams of education though the dominance of female students

is least pronounced in the B. Com stream and highly pronounced in both the arts and

science streams. In fact table 1.36 shows that the dominance of women increases as we

move up to the post-graduate arts and science courses. There are a number of reasons for

the predominance of women in undergraduate arts and science education. Among those

observed is the higher possibility that boys drop out after the higher secondary to pursue

employment or to undergo training in such categories of work as driving, plumbing or in

construction labour or that they take up the more job oriented technical and professional

18

courses in higher education. Indeed, boys are seen to dominate over girls in some of the

job oriented strands of professional and technical education as is evident in their

domination over engineering and polytechnic enrolments in higher education but not in

medicine.

Table 1.42 shows that girls have dominated the undergraduate arts and science courses

since at least 1990. This trend was first established in colleges under Kerala university

and MG university and only since 1990 in colleges under Calicut university. Table 1.42

shows that in 1990, boys had a slight edge numerically over girls in Calicut university.

However, in the later years shown in table 1.42, the universities in the Malabar region

Calicut and Kannur are not very different in terms of the predominance of girls over

boys.

Teachers in arts and science colleges, 1999-2007

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

year

Male

Female

Tot al

Source: Government of Kerala, various issues

Women have also tended to dominate teaching as a profession very generally. However,

the extent of their dominance declines as we go higher in the levels of education (Eapen

and Kodoth, 2003). The chart above shows that the total number of female teachers has

been declining since 1999 and their share among total teachers declined from 55 per cent

in 1999 to 45 per cent in 2005-06. As against a consistent decline in the share of female

19

teachers, the share of male teachers has increased alongside an overall decline in the total

number of college teachers since 1999. However, the data published in the Economic

reviews (GoK 1984 to 1998) shows that since the 1980s right up to 1997 males

comprised about 60 per cent of arts and science college teachers. From 1998 to 2003 this

ratio favoured women but since then it has been reversed. The delinking of pre degree

courses started in 1998 and the process is said to have rendered nearly 2500 teachers

surplus in the aided colleges alone. Some years before de linking was completed there

was considerable anxiety regarding the status of teachers in private aided colleges. It is

believed that the private colleges anticipated restrictions on appointments and made

efforts to fill in vacancies between 1995 and 1998. Nevertheless, there is an overall

decline in the number of teachers in arts and science colleges after 1998 alongside a

reversal of the sex ratio. It may well be that a fairly large number of male teachers retired

and the new appointments were women. It is notable that the decline in the number of

teachers preceded the ban on appointment of teachers in the private aided segment only in

2004 (G.O. (MS) No 63 / 2008/H. Edn., dated June 23/6/08) hence the latter could only

have exacerbated an already difficult situation.

Table 1.41: Number of Arts and Science colleges in Kerala by management

UNIV 1990 1996 2003* 2006**

Total Govt Aided Un A Govt Aided Un A Govt Aided Un A

Kerala 9 37 6 9 37 13 9 37 14

Calicut 22 56 17 16 44 31 17 45 50

MG 7 55 2 7 55 37 7 56 57

Kannur - - - 6 12 19 6 12 46

Total 170 38 148 25 38 148 100 39 150 167

*In the previous year there were only 38 unaided colleges. **In 2008 the number of unaided colleges

reported down to 153. Source: Directorate of Collegiate Education, Government of Kerala (various years).

20

Table 1.42: Girls as a proportion total students enrolled in the degree courses

UNIV 1990 1999 2002 2008

Total F % Total F % Total F % Total F %

Kerala 41169 56.67 45763 66.54 49246 62.57 46670 64.71

Calicut 38008 49.34 38268 59.82 38974 61.16 43978 64.38

MG 38578 60.30 36170 62.11 44067 60.66 40516 64.95

Kannur - - 11747 62.06 13692 55.90 36248 66.06

Total 117755 55.49 131984 62.96 145979 61.00 167412 64.98

Source: Government of Kerala (ER) various issues

1.5 The Problem and Methodology

At the state level the relatively slow pace of expansion of the higher education sector

evident from the previous sections (notwithstanding the more recent expansion of the self

financing segment) may be interpreted as a constraint to access. Further, constraints to

entry into higher education may be a cumulative problem i.e., the inability to transit

successfully from the secondary or higher secondary levels. This may include a) the poor

performance at the higher secondary and secondary levels, b) inability to continue in

education on account of economic compulsions or social disadvantage (also a problem of

equity), or c) drop out at the lower levels to gain job oriented informal training in tradable

formal or informal sector skills.

Gender and caste constraints to access are differently poised in the context of Kerala.

Recent work on entry barriers to technical and professional education note that caste is an

important basis of exclusion posing problems in the access of SC/ST and OBC students.

Further, the problems of access and equity intersect in important ways especially with

respect to gender and caste. Gender presents a less straightforward case of exclusion

with higher levels of enrolment of women relative to men in Kerala. While women

exceed men in terms of GER, far higher levels of unemployment of higher educated

women relative to men (and to women at the all India level) raise many questions

(Kodoth and Eapen, 2006). Educated unemployed women are known to have strong job

preferences linked to social norms and employment of higher educated women is

21

concentrated in the care sectors that are already identified as appropriately feminine.

How is this expected to inform our concern with higher education as a sector? A review

of literature on the global south suggests that higher education unlike literacy or primary

education is associated with less restrictive gender norms and hierarchies (Malhotra et al,

2003). Clearly this raises a whole set of questions regarding the influence of processes

within higher education (curriculum, pedagogy and environment) in shaping or sustaining

restrictive gender norms or enabling students to challenge them. In other words, we need

to probe higher education as a gendered process and explore how it shapes and genders

subjectivities. This distinctness of the gender dimension of higher education has not

entered so far into the policy discussion.

13

Quality of education and equity are key policy concerns. This is reflected in the

emphasis on restructuring curriculum and pedagogy in the draft higher education policy.

Policy interpretation of equity is in terms of the likelihood that it will be compromised

through privatization or the growth of self financing, which it sees as motivated towards

profit and against the interests of the general arts and science segment. As against this

there has been little concern with the status of physical and social infrastructure or the

role of party politics within higher education (despite its high visibility) especially in

terms of its implications for quality of education and its differential influence in terms of

gender, caste and class.

We propose to approach the question of access in relation to several dimensions:

a) Does the rapid pace of growth of higher educational opportunities in the self

financing sector at the state level and the growth of the self financing courses in

the government and aided colleges suggest that there is greater need than is being

met by the publicly funded sectors?

13

Currently, policy considers women along with the social deprived groups as an access and equity

concern. See U R.Ananthamurthy Committee. 2008. The Kerala State Policy on Higher Education Policy:

Draft for discussion, Trivandrum: Kerala State Higher Education Council. Committee for Restructuring

Undergraduate Education. nd. Report. Trivandrum: Kerala State Higher Education Council.

22

b) Does the narrow range of courses offered in the self financed segment suggest a

growing demand for specific kinds of courses as against that which is available in

the publicly funded segment?

c) What are the expressed preferences of students as may be evident from the shift

from science at the higher secondary level to commerce or arts at the degree

level?

d) How does the uneven regional pattern of distribution of enrolment in different

courses in colleges across universities and district inflect the question of access?

e) Given the overall predominance of girls over boys in arts and science colleges,

virtually across courses how do we interpret the gender dimension of access? Is it

nuanced by the influence of gender interests and identities in defining access to

arts and science education as well as the nature of gender socialization imparted

through higher education?

f) Have lower castes and especially SC and ST students been able to gain access to

arts and science education? What does the discourse on caste tell us regarding the

access these students have?

g) Is the rigidity of college-based higher education with respect to the timing of

classes restricting the access of economically disadvantaged students? How can

the needs of these students be brought within the fold of regular teaching

institutions?

On the question of quality of education on offer in the arts and science colleges, we will

examine the adequacy and access that students have to basic facilities in colleges

including social and physical infrastructure, IT facilities, library resources, tutorials as

well as support facilities like add-on courses, psychological counseling and career

guidance. A key aspect that we subject to analysis is the nature of politics or its absence

on campuses and its influence in fostering quality education by influencing college

environment. Here we would like to explore the influence of the political environment

(whether excessive politics or its absence) in constraining or promoting citizenship

education and democratic participation. We will also examine the standard indicators of

23

quality as they apply to the colleges such as accreditation with NAAC, rate of success of

students and so on.

The equity question has been the most difficult for us to explore, especially in terms of its

qualitative dimensions. However, we have made an effort to probe the access that

socially and economically deprived students have to higher education at the college level

as well as the state level and the experience of these students. Importantly the equity

question intermeshes also with that of gender and politics, where politics is used to

segregate women or to discipline them.

1.6 Methodology and Data base

1.61 Research questions

1. Is there greater demand than opportunities available in the higher education sector?

Hypothesis: In gross terms, there are more opportunities in the higher education sector in

the state than are currently being utilized.

2. How is the demand versus opportunities question expressed from within the higher

education sector?

Hypothesis: Demand for the general arts and science segment, in terms of students who

opt for it, derives from those ranging from (at two ends of the continuum) those with a

well defined academic (intellectual) interest in pursuing higher studies to those who are

putting in time that is likely to be valued in cultural terms. There are likely to be several

categories within this range, including importantly those who failed to get admission into

any or in their preferred technical and professional courses.

3. Are gender and caste the prominent basis of social exclusion in higher education?

24

Hypothesis a: Womens dominating presence in the general arts and science segment of

higher education serves cultural ends, most importantly as an aspect of grooming for a

desirable marriage.

Hypothesis b: The under-representation of the lower castes, tribal and coastal fishing

groups is on account of the lack of adequate staying power (economic resources) and/or

the inadequacy of expected rewards.

4. How do different stakeholders view the problem of quality in the general arts and

science segment of higher education?

Hypothesis: Conflict of interest among different stakeholders renders the problem of poor

quality not only acute but also difficult to reform.

5. Do students from dalit and tribal communities experience higher education differently

from upper caste, middle class students?

Hypothesis: Differential experience of students on the basis of caste, ethnicity and gender

limits the potential of higher education to combat social basis of discrimination.

1.62: Project Activities

The study took up two major sets of activities - building up baseline information on arts

and science colleges in the Government and aided sectors and detailed survey and

interview based research in six selected colleges. We conducted the survey in an

additional college, chosen for its isolated location but did not conduct interviews there.

A limited amount of information, regarding mostly courses, availability of seats and

management affiliation was available from the four affiliating universities, the

Department of Higher education and the websites of individual colleges. We sent out a

questionnaire to all the arts and science colleges in the government and aided sectors and

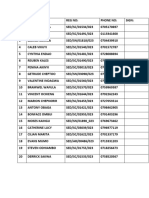

received completed responses from 115. Table 1.61 provides a district- wise distribution

of arts and science colleges in the government and aided sectors in Kerala and show that

25

the distribution of responses across districts is random i.e., there is no systematic bias in

the colleges that did not respond. The questionnaire was designed to provide us with data

to understand the need versus opportunities question on the courses offered, regional

distribution of demand for courses, availability of self financing courses, the problems

faced by colleges and some indicators of the performance of students and teachers. We

included questions to identify the management, student enrolment versus capacity over

the last two years, availability of teaching staff, library facilities and some indicators of

quality awards received, pass percentage and NAAC accreditation.

The private aided colleges are owned and managed by a diverse set of agencies. The

major social / religious communities have significant stake in the management of arts and

science colleges in Kerala. We have categorized these managements according to the

major community categories they represent - Christian, Hindu and Muslim. Among these

the colleges managed by various Christian groups form the single largest and are very

diverse ranging from what resemble corporate managements such as those of the

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church and Malankara Orthodox church, which have

state-wide networks of colleges to the diocese societies of the Catholic churches and the

Yacoba Sabha, which manage individual colleges. There are also Catholic missionary

societies, which are involved in managing at least a handful of colleges, the CMI

Carmelites of Mary Immaculate and CMC Congregation of Mother Carmel. Corporate

managements are those of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP Trust)

and the Nair Service Society (NSS), caste associations seeking to represent two major

castes, the Ezhavas (OBC) and Nairs (forward) respectively, and the Muslim Educational

Society, (MES) set up in Malabar to represent the interests of the Muslim community.

The Devaswam boards, set up to manage temples, too are involved in the management of

colleges. Apart from these groups there are a number of colleges run by local

independent trusts, including a number of independent Muslim and Hindu trusts.

26

The responses received have been compiled in table 1.62 as college responses according

to sex composition (whether they are girls only or mixed)

14

and category of management

i.e., whether it is run by Christian, Muslim or Hindu organizations or by other

organizations. The table shows that the responses include 60 per cent of colleges in

Kerala, with 66 per cent of Government colleges and 59 per cent of aided colleges. The

single largest number of colleges in the responses is from Christian managements

followed by Hindu and Government. Table 1.63 classifies the college responses

according to sub groups of management and table 1.64 and 1.65 provides the

classification of college responses by university of affiliation. The latter shows that MG

university has the lowest representation in the responses whereas all Kannur university

colleges responded.

The second set of activities came under the purview of detailed studies undertaken at six

selected colleges in Kerala. We had proposed to conduct in depth investigations at six

colleges distributed across region, universities and different managements in Kerala.

Table 1.67 shows the distribution of these colleges, where more detailed investigations

were conducted. We selected two Government colleges, College G1 in a city in south

Kerala, College G3 in a northern hill district, two Catholic colleges, College A2 and

College A3 one each from a Syrian and a Latin Catholic diocese, an caste association

managed college College A1 - from among the caste associations / Hindu charitable

Trusts and an independently managed Muslim college, College A4. College A3 managed

by the a diocese society of the Syro Malabar church is a womens college while College

A2 is mixed and represents the Latin Christian community converts from the socio-

economically underprivileged coastal communities. Both these colleges are located in

the territorial jurisdiction of MG University, where Christian missionary influence on

education was strong. College A1 is in central Kerala and College A4, managed by an

independent Muslim trust, is in northern Kerala. The additional college taken up for

survey College G2 - is a Government college in an eastern hilly region of the far north.

14

Two colleges, SB College, Changanassery and St Thomas College, Pala, restrict their undergraduate

programme to boys only and it has been included with the mixed colleges (Directorate of Collegiate

Education).

27

As the functioning of colleges in Kerala is affected considerably by the nature of student

politics they sustain we also provide the status of politics in each of the colleges selected

for study. In three of the colleges (two Christian and one Hindu) political activism is

banned on campus; the parliamentary system of elections to the students council is

practiced in two while the third was still in the process of transition. Student politics is

permitted and was the basis of elections to the students council in the two Government

colleges and one Muslim college. In the additional college we took up for survey too

politics is permitted. Apart from regional distribution and representation of diverse

management groups we also had to keep in mind the possibility of gaining access to the

college.

In each of the colleges, we did a survey of students of select second year degree courses,

usually selecting at least three courses in each college an arts, a commerce or

economics course and a science course. There have been some variations in this on

account of problems encountered during the survey. Additionally, as mentioned, we

conducted the survey at a Government college, College G2, the far north of Kerala.

Though this college was not taken up for detailed investigation, its remoteness as well as

the low density of colleges in the district (only five in the government and aided

segments) prompted us to include it.

Table 1.66 shows the distribution of students surveyed by their course and main subjects.

In most colleges, we have surveyed students from more than three courses. College G2

has only four courses, which does not include a science course, hence we surveyed

Economics and Functional English. In the colleges selected we found a greater diversity

of arts courses hence where we took up an applied or specialized arts course (such as

Communicative English or Development Economics) we have also attempted to take up a

general course. Further, the pure science class strength tended to be smaller than the arts

courses. On account of these factors, the number of students surveyed in the arts courses

is about double that of the science courses. We have tried to select either commerce or

economics in each college because these were the highly preferred courses owing to the

perception that the offer greater job potential. The survey sought to generate information

28

regarding student preference for arts and science education, their perceptions of college

facilities, curriculum and environment, their family background, sources of finance for

education, whether they were engaged in paid work and their involvement in politics.

Table 1.68 provides an overview of the surveys in seven colleges in terms of the coverage

of students and sex composition. About 72 per cent of students surveyed were girls.

While this is not surprising, given the predominance of girls in undergraduate arts and

science courses, there may be an under-representation of boys, who much more than girls

tended to be absent from classes. Further, we have also selected an all girls college. As

against this however in College G1, 46 per cent of students surveyed were boys. It is to

be noted that College G1 has a sex ratio that is closer to parity because of a ceiling of 33

per cent on the admission of girls to eight undergraduate courses. The rationale of the

ceiling is that the Government Womens college in the same city offered these courses.

We also conducted interviews with teaching faculty in these colleges regarding various

aspects of higher education. A third set of activities we planned were group discussions

with students but we were able to conduct these only in five colleges. In some colleges

we were able conduct interviews as well with a few students. Further, the stake holder

interviews planned were conducted in these colleges with representatives of teachers

associations, principals of colleges and one of the managers. We also spoke a few

teachers and several Principals (sometimes recently retired) from colleges not taken up

for detailed study.

Some of the colleges threw up distinct overarching questions, which served as a lens to

understand broader questions of access, quality and equity. In others, there was no single

big issue and we probed a variety of questions. In the case of College G1 it was the

nature of student politics, which was controlled by the SFI in a ruthless manner affecting

the everyday aspects of life on the campus. In contrast to the larger than life picture of

politics at College G1, in College A2 the overarching issues seemed to be the larger than

life role of the management, which had not only put into effect a ban on politics literally

suppressing voices of dissent but was generally perceived as excessively interventionist

29

and controlling. Here the ability of departments to function well depended on the ability

to negotiate with the management. In College A3 college gender socialization was a

crucial issue that was dispersed over curricular and non-curricular aspects of education.

In COLLEGE A1 the ineffectiveness of the management was a shaping feature of the

profile of the college even as in the case of Farook, it was the deft manner in which the

management negotiated issues. Though College G3 was selected because of its location

in an area with a significant tribal population we were unable to generate adequate

discussion on this issue but will go into some of the problems encountered.

Table 1.62: Distribution of College responses by district, sector and sex composition

Figures in parenthesis are percentages, Source: Response from Kerala colleges

Management of colleges Sample

colleges

Sex

composition Aided

District

Num

ber

% of

total

Mixed Girls

Govt.

M H C Othe

r

Total

aided

Trivandrum 17 85 15 2 6 2 5 4 0 11

Kollam 12 92 11 1 1 1 7 3 0 11

Pathnmthta 5 55 5 0 0 0 2 3 0 5

Alappuzha 2 17 2 0 0 0 2 0 0 2

Idukki 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Kottayam 11 52 8 3 1 0 0 10 0 10

Ernakulam 5 20 4 1 0 0 0 5 0 5

Trissur 16 80 12 4 3 1 4 8 0 13

Palakkad 9 90 9 0 3 1 5 0 0 6

Malapuram 12 100 11 1 3 7 1 1 0 9

Kozhikode 8 57 7 1 3 2 1 2 0 5

Wayanad 2 33 2 0 1 0 0 1 0 1

Kannur 11 100 10 1 2 2 2 1 4 9

Kasargod 5 100 5 0 3 0 0 1 1 2

Total

115 60.8

101 14 26

(66.7)

16 29 39 5 89

(59)

30

Table 1.61: Distribution of Arts and Science colleges over districts and universities

* Percentage of colleges that responded to the CDS questionnaire; Source: Government of Kerala

Districts University Govt. Aided Total % of total % of resp*

Trivandrum Kerala 08 12 20 10.58 14.78

Kollam Kerala 01 12 13 6.88 10.43

Pathanamthitta Kerala 0 02 02

Pathanamthitta M G 0 07 07 4.76 4.35

Alapuzha Kerala 0 11 11

Alapuzha MG 0 01 01 6.35 1.74

Idukki MG 02 06 08 4.23 0

Kottayam MG 01 20 21 11.11 9.57

Ernakulam MG 04 21 25 13.44 4.35

Trissur Calicut 03 17 20 10.58 13.91

Palghat Calicut 03 07 10 5.29 7.82

Malapuram Calicut 03 09 12 6.35 10.43

Kozhikode Calicut 06 08 14 7.41 6.96

Wayanad Calicut 01 03 04

Wayanad Kannur 01 01 02 3.17 1.74

Kannur Kannur 02 09 11 5.82 9.56

Kasargod Kannur 03 02 05 2.65 4.35

TOTAL 39 150 189 100 100

31

Table 1.63: College Responses by management sub groups

Management sub groups Number Percentage

Government 26 22.6

Catholic 15 13.0

Various Catholic Convents 6 5.2

Congregation of Mother Carmel 3 2.6

Carmelites of Mary Immaculate 3 2.6

Church of South India 4 3.5

Malankara Orthodox** 5 4.3

Mar Thoma** 3 2.6

Muslim Educational Society** 7 6.1

Nair Service Society** 11 9.6

Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam** 12 10.4

Various Devaswom Boards 4 3.5

Independent Trust * 16 13.9

Total 115 100.0

* Independent Trusts include 2 Hindu trusts, 9 Muslim trusts and 5 Others. ** Corporate managements.

Source: Response from Kerala Colleges

Table 1.64: College Response according to University of affiliation

University No of

Responses

Responses as

% of colleges

% distribution

of responses

% distribution

of Colleges

Kerala 32 69.56 27.83 24.34

MG 20 31.75 17.39 33.33

Calicut 45 75.58 39.13 32.80

Kannur 18 100 15.62 9.52

Total 115 60.84 100 100

Source: Response from Kerala Colleges

Table 1.65: College response according to sector

NUMBER OF COLLEGES Responses as a % of colleges University

Government Aided Government Aided

Kerala 7 25 67.57 77.78

MG 1 19 33.92 14.29

Calicut 12 33 73.33 70.59

Kannur 6 12 100 100

Total 26 89 59.33 66.67

Source: Response from Kerala Colleges

32

Table 1.66: Students surveyed over selected Colleges, Courses and Main subjects

Classes taken for survey in each of the seven colleges

CG1 C A1 C A2 C A3 C A4 C G2 C G3 Total

1 B. Com 0 47 35 3 29 0 36 150

.0% 43.5% 43.2% 2.4% 35.8% .0% 35.0% 23.4%

B. A. 73 42 24 70 34 40 44 327

71.6 38.9 29.6 55.1 42.0 100 42.7 50.9

2 Economics * 28 0 24 0 0 23 24 99

27.5% .0% 29.6% .0% .0% 57.5% 23.3% 15.4%

3 History ** 0 42 0 36 15 0 0 93

.0% 38.9% .0% 28.3% 18.5% .0% .0% 14.4%

4 Sociology 0 0 0 0 19 0 0 19

.0% .0% .0% .0% 23.5% .0% .0% 3.0%

5 Malayalam 30 0 0 1 0 0 0 31

29.4% .0% .0% .8% .0% .0% .0% 4.8%

6 English ** 0 0 0 33 0 17 20 70

.0% .0% .0% 26.0 .0% 42.5% 19.4% 10.8%

7 Political Sc 15 0 0 0 0 0 0 15

14.7% .0% .0% .0% .0% .0% .0% 2.3%

B Sc 29 19 22 54 18 0 23 165

28.4 17.6 27.2 42.5 22.2 0.00 22.3 25.7

8 Maths 0 0 0 41 0 0 0 40

.0% .0% .0% 32.3% .0% .0% .0% 6.2%

9 Home Sc 0 0 0 11 0 0 0 11

.0% .0% .0% 8.7% .0% .0% .0% 1.7%

10 Physics 0 0 22 0 0 0 0 22

.0% .0% 27.2% .0% .0% .0% .0% 3.4%

11 Botany 0 0 0 1 18 0 0 19

.0% .0% .0% .8% 22.2% .0% .0% 3.0%

12 Zoology 29 0 0 0 0 0 0 29

28.4% .0% .0% .0% .0% .0% .0% 4.5%

13 Electronics 0 0 0 0 0 0 23 23

.0% .0% .0% .0% .0% .0% 22.3% 3.6%

14 Chemistry 0 19 0 1 0 0 0 20

.0% 17.6% .0% .8% .0% .0% .0% 3.1%

Total 102 108 81 127 81 40 103 642

% 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Note: * Including Development Economics at Wayanad, ** Islamic history at College A4and ***

Communicative English (SFC) at College A3 and Functional English at College G2, One student from

Computer science in College A3 college has been included in Maths.

33

Table 1.67: Colleges selected for fieldwork by sector, management and region

Name

Of

College

Univ. Region

LSG /

Location

Sector Management Politics

College G1* Kerala Travancore /

South

Corporation /

Urban

Govt. State No ban

College A3 MG Travancore /

South

Municipality /

Urban

Aided Syro Malabar Ban

College A2 MG Cochin /

Central

Corporation /

Urban

Aided Latin Catholic Ban

College A1 Calicut Malabar /

Central

Panchayat /

Rural

Aided Caste

Association

Ban

College A4 Calicut Malabar /

North

Corporation /

Urban

Aided Independent

Muslim Trust

No ban

College G3

**

Kannur Malabar /

North

Panchayat /

Rural

Govt. State No ban

Source: Field survey. * UC, ** College G3.

Table 1.68: Survey of Students in Select (7) colleges by sex composition

Name of College Sex composition

Male Female

Total

College G1 46 (45.1) 56 (54.9) 102 (100)

College A1 30 (27.8) 78 (72.2) 108 (100)

College A2 32 (39.5) 49 (60.5) 81 (100)

College A3 0 127 (100) 127 (100)

College A4 23 (28.4) 58 (71.6) 81 (100)

College G2 * 12 (30.0) 28 (70.0) 40 (100)

College G3 39 (37.9) 64 (62.1) 103 (100)

Total 182 (28.3) 460 (71.1) 642 (100)

Figures in parenthesis are percentages. Source: Field survey; * (included only in survey)

Chapter 2

Interpreting Access, Probing Equity

There are people who are not getting opportunities to join higher education. Donations

should be banned (Student of College A1)

2.1 Introduction

In discussing the question of access to higher education in Kerala in the previous chapter,

we noted that the gross enrolment ratios varied widely depending upon the data set that is

used to compute it with the SES underestimating it (very considerably according to

some accounts) and the NSS and Census tending to provide overestimates. Further,

while the GER for Kerala is significantly below the all India average according the SES,

it is significantly above the all India average according to the NSS and Census. The