Professional Documents

Culture Documents

One, or Several (Blue) Wolves?

Uploaded by

daugscho0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

91 views5 pagesAkira Mizuta Lippit

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAkira Mizuta Lippit

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

91 views5 pagesOne, or Several (Blue) Wolves?

Uploaded by

daugschoAkira Mizuta Lippit

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

131

One, or Several (Blue) Wolves?

Akira Mizuta Lippit

A black wolf with yellow eyes framed in a blue box stares out from the fat image. Elad Lassry's photograph

Wolf (Blue) (2008j (fig.1j shows the full body of a wolf, seen from the side. lts front legs are mounted on

a mark, a wooden box used to position the subject. The wolf is an actor, and the photograph is staged.

(Lassry often works with found objects and images, sometimes re-photographing photographs, but here he

composed and took the photograph of this trained wolf himself, aided by two wolf trainers. lt is a primary

image.j A slight blur in the wolf's face reveals on closer inspection a second pair of eyes, set slightly apart,

side-by-side, superimposed onto the wolf's face. And not only the eyes, but also its legs, front and hind, are

doubled. The hind legs noticeably, the front legs less distinctly. One wolf or two? The same wolf twice? One

wolf in two different places and instants of time? Lassry's Wolf (Blue) superimposes two images of a wolf,

one or more wolves, onto an apparently single body. Not a singular body, as few are even when they are,

but a single body marked by too many eyes, too many legs, too many bodies. Not the entire body, but the

eyes and legs and perhaps other stretches of body indiscernible. The singularity of Lassry's image resides

in the photograph, not the animal's body. But the work's singularity is disrupted by the doubling effect

that generates a feeling of movement, of still life in motion. Of wolves wolfng. The feeling of a perception,

because the perception itself remains obscure, blurred as it were in the intensity of feeling that Lassry's wolf

or wolves provoke. (Feelings, affect, where the perception is elusive.j lt is not clear from the image whether

there are separate wolves fused together, or two separate images of the same wolf merged together at a

slight distance. Two wolves or two images? Before this image one feels the separation of wolves from a wolf,

one senses the multiplicity, a feeling separating the perception from the image, one image from another.

The multiplication of eyes and legs on the body of this animal recalls the representation of movement in

various histories of photography, most notably tienne-Jules Marey's (1830-1904j chronophotography (fg.2j, a

palimpsest of time-lapse images fused onto a single surface. Following Eadweard James Muybridge's (1830-

1904j serial photographs of animal locomotion (fg.3j, Marey produced an image of movement by merging

discrete instants of time onto a single frame, stretching his bodies across the plane of his images. His elastic

bodies move across the single plane of the image as still movements. For both Muybridge and Marey, the

subjects of their serial and chrono-photographs are often animals, human and non-human animals. ln their

work, animals become fgures for the photo-representation of mobility, of animated photography. ln contrast

to Muybridge's animal movement rendered in multiple photographs, the motion situated between the stills,

in the interstices; or Marey's condensation of multiple images that create a single frame of bodies in motion;

Lassry's wolf appears to be standing still, even posing. Nothing appears to move, yet the feeling of movement

persists everywhere in this image. Where does this sense of motion come from? From the wolf? From the

wolf splitting into wolves? Or from the attentive looking of the wolf's proliferating yellow eyes? The trace of

movement in Lassry's wolf, if it is movement at all, is minimal, a nearly imperceptible trace of blur, ex-centric

to the image. Wolf (Blue) captures the action of a still body. lt reveals looking as a visible action. One sees in

this image, the act of another looking, the movement of an other's look.

The question returns, over and over again: one, or several (bluej wolves? One or more bodies, one or more

instants of time pressed onto a single surface, and then rendered in deep blue? Does Lassry's blue box

give the wolf stereoscopic depth? ls this the source of his movement, the relief, a black wolf out of the blue?

Lassry's wolf looks outward from a box that produces a trompe-loeil frame rendered in space. At work in

this wolf's look, its doubled vision outward is the image of depth rendered fat. Lassry's use of shading in the

lower background produces in this blue box-frame, a room, a camera obscura that echoes the wolf's black

body.

lmages of multiple eyes and doubled animals appear periodically across Lassry's uvre. Man 071 (2007)

(fg.4j, also framed in a blue box, features a smiling man, naked, and in medium shot, with two sets of eyes.

His glance is askew, but his blurred eyes emit the anamorphic effect Lacan ascribes to Hans Holbein's

Ambassadors (1533j (fg.5j: l am being watched, photographed, and in this oblique image of surveillance, l

discover myself seeing myself, the mise-en-abme of autoscopy. One is tempted to add that the attentive look

of the subject portrayed appears everywhere in Lassry's work, not only in those works where he emphasizes

the multiplication of eyes. The mother cat of Burmese Mother, Kittens (2008); the Untitled (2007) ballerinas,

the smiling Philip Pruitt (2009j, surrounded by a bed of purple fowers, the smiling Czech Girl (2009j, slightly

discolored in her black bra, the serious Boys (2009j, the ghostly man and woman of Textile (For Him and Her)

(2009j, and of course the many and multiple Anthony Perkinses that produce over the course of Lassry's work

an acute sense of being observed (by himj. The intensity of looking appears all over Lassry's work, as one of

its themes. But in Wolf (Blue), the visualization of seeing emerges onto the surface of the image.

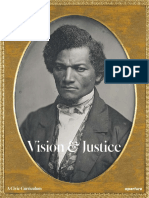

(Figure 1j

Elad Lassry, Wolf (Blue), 2008

C-print, painted frame

11.5 x 14.5 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

(Figure 2j

Etienne-Jules Marey, Cheval blanc au pas, 1886

(Figure 3j

Eadweard James Muybridge, High-speed sequence of a

walking lion from the series Animal Locomotion, 1887

Courtesy of the Eadweard Muybridge Collection/

Kingston Museum/ Science Photo Library/ PPS

(Figure 4j

Elad Lassry, Man 071, 2007

C-print, painted frame

14.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

133

Lassry's wolf is taken from two sets of negatives, which were scanned then merged (sandwiched," he saysj, a

practice, Lassry notes, common in Bauhaus photography. The multiplication of eyes, the grafting of additional

sets of eyes appears regularly throughout the history of photography, from the constructivist (fg.6j as well as

Bauhaus traditions, and in many portrait photographers, from Alvin Langdon Coburn (fg.7j to Weegee. l have

always been intrigued," he says, perhaps even panicked by the option of multiplicity."

1

Lassry's intrigue and

panic extend outside of wolves and into women as well as men. Guinevere (Green) (2009j (fg.8j shows a

naked woman framed from the hips up melded into a background of green hexagons. The box-frame is green,

and the woman is both before and behind the surfaces of hexagons, her body at once receding and emerging

from the ground. Guineveres entire body appears doubled, a trace of movement forward or backward, as if

moving in and out of time. Two pairs of eyes appear on her face, but the individual values of each set are less

equal than the Wolf's or the Man's. Felicia (2008j, presents another point on Lassry's scale of multiple eyes,

blurrier than Wolf or Man, more pronounced than Guinevere's third and fourth eyes. Felicia is framed in a light

green box, fully clothed, a red AlDS ribbon pinned on her white blouse. Colored circles form the background

surface. Men, women, and wolves, proliferate in Lassry's colored multiplicities, in some instances named

with personal pronouns, in others with generic designations, a species or a gender. Each of them associated

with a color or set of color intensities.

But why a wolf, this wolf? The late Jacques Derrida had a thing about wolves, about remembering not to

forget about wolves, as he puts it in his fnal seminar. So," he says in the Third Session" of his last seminar,

The Beast and the Sovereign (2002j, let's not forget, let's not neglect the wolves, from one year to the

next."

2

Why this reminder? ls neglecting or forgetting about wolves a phobia, related perhaps to the very

fear of wolves? ls there such a thing as the fear of forgetting wolves? This imperative to remember becomes

a refrain for Derrida. Later he says, As if l were myself, let's never forget it, a wolf or even a werewolf."

3

And maybe this exhortation because, One always forgets a wolf along the way."

4

ls the wolf so forgettable

than even when one remembers one forgets, always a wolf along the way"? (Even when one remembers

to remember?j Or maybe one suppresses the wolf, the many wolves, reducing it always to one wolf and

forgetting, repressing the others. One wolf instead of many, the many wolves that are always there in the

place where one stands. Perhaps this is what one has to remember, that there is never only one wolf; where

there is one, there are many.

There are many stories and multiple histories of men and women and wolves; some that begin with boys, girls,

and wolves. Sergei Pankeyev's story is one, or rather many. lt is a story of boys, girls, and wolves (of fathers,

teachers, maids all bound by a community of wolves), but also of names and secret names, and of entirely

secret languages

5

. But most importantly, his is a story of perception, of the perceptions of wolves to be

precise. lt centers on an image that turns and returns repeatedly frst in a dream, which is then reproduced in

a drawing, reduced eventually through analysis to a single wolf, to the fgure of a wolf, from wolves to the wolf

as such. (But even before the dream, there are more images--there always are.j Pankeyev became the Wolf-

Man," projected across multiple landscapes and backgrounds; the multiple optics and eyes that inform his

intrigue as well as his panic refected in the wolves' eyes that gaze at him from inside his dream. The dream is

a scene of visualization of seeing, like Lassry's Wolf, an image of perception. lt is also an image of movement,

not of the wolves, which are stationary, but of the movement of an image from one screen to another, one

surface to another, one frame to another.

Sergei Pankeyev, a wealthy Russian who suffered from a phobia of wolves, underwent analysis with Sigmund

Freud in vienna from 1910 to 1914, and several times afterward until 1919. Freud declared Pankeyev cured,

a triumph of psychoanalysis that demonstrated its therapeutic effcacy. Pankeyev disagreed, and his case

became the focus of a sustained narrative thread that came to stand for a referendum on the validity of

psychoanalysis. Numerous theorists, analysts, historians, and journalists have commented on this case

and Freud's handling of it, generating a vast polemics that challenge the viability of psychoanalysis as such.

Among those voices is Pankeyev's own, collected in an anthology of writings by and about him, The Wolf-Man

by the Wolf-Man.

6

Central to this case, known sensationally as the Wolf-Man," clinically as From the History of an Infantile

Neurosis (1918 [1914|j, is Pankeyev's dream. From Freud's multiple citations of it:

I dreamt that it was night and that I was lying in my bed. (My bed stood with its foot towards

the window; in front of the window there was a row of walnut trees. I know it was winter when

(Figure 5j

Hans Holbein the Younger, Jean de Dinteville and

Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors'), 1533

The National Gallery, London

(Figure 6j

Gustav Klutsis, Boris Kulagin, 1929

Silver gelatin print

(Figure 7j

Alvin Langdon Coburn, Ezra Pound, 1917

Silver gelatin print

(Figure 8j

Elad Lassry, Guinevere (Green), 2009

C-print, painted frame

14.5 x 11.5 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

I had the dream, and night-time.) Suddenly the window opened of its own accord, and I was

te|||hed to see t|at some w||te wo|ves we|e s|tt|ng on t|e o|g wa|n0t t|ee |n f|ont of t|e w|ndow.

There were six or seven of them. The wolves were quite white, and looked more like foxes or

sheep-dogs, for they had big tails like foxes and they had their ears pricked like dogs when they

pay attention to something. In great terror, evidently of being eaten up by wolves, I screamed

and woke up."

7

Pankeyev describes the clear and life-like picture of the window opening and the wolves sitting on the tree."

8

Among the key features of Pankeyev's dream are the meta-perceptual qualities of the dream, as if the dreamer

is dreaming about dreaming; the strong impression of white, the white wolves and the diffuse color of winter

as well, perhaps; the indeterminate quantity of wolves, six or seven" in Pankeyev's account, only fve in his

rendering of the dream; and the indeterminate quality of the wolves themselves, which appear to be fuidly

canine, shifting between foxes and dogs.

ln his interpretation of Pankeyev's dream, Freud focuses on the latent sexual content of the dream, in

particular the potent fgure of the wolf and wolves, but also on its literary origins, the fairytales Little Red

Riding-Hood" and, Freud suggests, The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats." The fear of wolves that gives

Pankeyev his nickname Wolf-Man" is the fear of being eaten by one or more wolves, of being assaulted,

but even more profoundly for Freud, the imagined origin of Pankeyev's fear of wolves, a primordial scene

of perception, the primal scene in which, Freud speculates, Pankeyev saw his parents engaged in sexual

intercourse, a tergo, three times repeated."

9

(The image of the wolf also comes from his sister, who taunted

Pankeyev in childhood with the picture of an erect wolf on its hind legs, most likely according to Pankeyev, an

illustration from a household copy of Little Red Riding-Hood."j

The primal scene that Freud invokes serves in this instance as the origin of Pankeyev's phobia, his

simultaneous experience of sexual desire and fear, intrigue and panic," to use Lassry's nuances, but also as

the frame for the second scene of perception. The primal scene is never one, never remains one, but sets into

motion an entire train of sexual distress and intrigue, creating a visual sequence that moves from the primal

scene to Pankeyev's numerous fantasies, his dream, and his sketch of the dream. Even deeper than the

symbolic fear represented by the wolf and Pankeyev's wolf phobia, is the primal fear of seeing itself, the deep

affect of visuality and perception rendered by the opening window in Pankeyev's dream. Optophobia, the fear

of opening one's eyes. ln his dream, seeing produces feeling, and this feeling travels with each screen, and

each iteration of seeing. The serial visuality of the Wolf-Man's dream of wolves is embedded in every aspect

of the account, and the primal scene emerges in this instance not so much as the primal scene of adolescent

sexuality, but as the primal scene of an obscene visuality transmitted as it were from one medium to another.

Everything trembles in the multiplicity of Pankeyev's dream: six or seven wolves, and then fve; the row of

walnut trees; the protean wolf, fox and sheep-dog at frst, then father, teacher, and other devouring fgures; his

parents' coitus a tergo, three times repeated"; and the seriality of images, tableaux, surfaces, and screens

that follow from the primal scene. The mobile immobility of Pankeyev's dream also draws Freud's attention,

the factors," he says, of attentive looking and of motionless" that Pankeyev emphasized. ln Freud's

interpretation, the attentive looking, which in the dream was ascribed to the wolves, should rather be shifted

on to [Pankeyev|."

10

The wolf--the wolves--are also refections of Pankeyev himself, projections of his own

looking. At a decisive point," says Freud, a transposition has taken place."

11

Pankeyev is himself the wolf

he fears, and what he sees in the dream looking at him, is the scene of his own looking. He is truly, in this

scene, a Wolf-Man."

At the center of Freud's interpretation of Pankeyev's dream are the tropes of transposition and reversal, a

general feature of psychoanalysis in which an object or action comes to represent its exact opposite. Homes

become unhomely, horrors become wishes, and revulsions turn out to be desires. lf one transposition or

reversal" already marks the rhetoric of Pankeyev's dream, then what if other areas of signifcance were also

inscribed in reverse, transposed? What if motionlessness was in fact an image of excessive, violent motion?

ln that case," Freud concludes, instead of immobility (the wolves sat there motionless; they looked at him

but did not movej the meaning would have to be: the most violent motion. That is to say, he suddenly woke

up, and saw in front of him a scene of violent movement at which he looked with strained attention."

12

The intense look of the wolves in Pankeyev's dream is, according to Freud, an image of Pankeyev's own

(Figure 9j

Elad Lassry, Two British Shorthair Cats (BSH), 2009

C-print, painted frame

11.5 x 14.5 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

135

attentive looking, transposed from his own eyes to those of the wolves; his own intensive probe embodied

by the wolves looking at him. An image of himself perhaps seeing himself look. And by the same logic, the

motionlessness of the wolves that Pankeyev emphasizes in his dream is actually a fgure for the most violent

motion." How is this possible, everything in reverse? Everything is upside-down in Freud's interpretation:

objects are subjects, the wolves that are not even wolves all the time (sometimes foxes and sometimes sheep-

dogsj are always me, stillness is frenzy, white is black, or blue perhaps. Applying the same logic or extending

it, maybe the white wolves are actually blue, like Lassry's Wolf (Blue).

13

The perverse logic of perception in which what one sees is seeing as such, the seen as well as the scene of

seeing returns like Pankeyev's dream in Lassry's image. It returns, the second or after-image of the primal

scene. l see the wolf looking, but it is a second wolf that looks at me; and that second wolf is me, watching

attentively. Watching myself attentively watching attentively. What Lassry's Wolf (Blue) makes visible is not

a scene of internal anguish like that which erupts in Pankeyev's images, the visualization of anxiety, fear,

desire, despair, and so on, but rather the scene of seeing those interiorities, those intensities. ln the stillness

of Lassry's wolf, one sees the tremor of an essential multiplicity, not only of the wolves and me, of selves

and other selves, of subjects and objects, of two and many more eyes, of depths and surfaces, of colors

and intensities, but of the irreducible scene of perception in which the single image--the singularity of vision

and the visible--assumed by each subject is always breaking into two or more. Everything breaks apart,

everything ruptures but while remaining composed. This is the law of Lassry's perception, the indescribable

calm of his frenzied images. One sees it acutely in Wolf (Blue) and the men and women with multiple, blurred

eyes, but also in Lassry's animal pairings, his animals at a remove from animality--in the pleading Two-

British Shorthair Cats (BSH) (2009j (fg.9j, in the metallic Two Elephants (2010j, in the transparent, petrifed,

sculptured Cat and Duck (2011) and Cat and Duck (Red) (2011), in the brass Cub, Raccoon (2011), in his

diptych Giraffe, 93040 (2011j, in the Tiffany Collie, Poodle (2011), in his pink, red, and white Herend (Three

Pigs) (2011j. The Apollonian cool is in constant state of disruption by the Dionysiac forces that see me

watching attentively. This happens everywhere throughout Lassry's uvre, not only in his images of wolves,

animals, men and women, boys and girls, but also in objects, in Persian Cucumbers, Shuk Hakarmel (2007),

in Lipstick (2009j, High Heel, Purse (2009j, in Ropes (2009j, in Nail Polish (2009j, in Papayas (2009j, and too

many more to mention. The singularity of perception is broken apart into pieces, shattered into a multitude of

transpositions and reversals that produce intensities in lieu of expressions.

The striking colors that mark Lassry's work, and which sometimes overtake them, like the white wolves in

Pankeyev's dream, function as perception-affects: colors are, like affects in dreams, asignifying. They are

forces, intensities, every bit as important to a work as symbols and narratives, but without literary (literal,

iterablej content. They render the affective dimensions of perception that elude signification but form an

essential part of it. Pankeyev's dream cannot exist without the whiteness of his wolves, just as the colors that

permeate Lassry's work form an irremovable dimension of it. ln color is multiplicity. ln fact, color may be the

clearest sign of a multiplicity that resists signifcation.

And this is what makes the scene of Lassry's perception of wolves and men and women a feeling rather than

a symbol of desire, an affect rather than the representation of an interiority or a surface. His are scenes of

static frenzy, everything moving in the motionless stir of the still image. Gilles Deleuze and Flix Guattari

understand this in their unforgiving critique of Freud's analysis. For them, Freud's greatest failure is his

inability to recognize the key feature of Pankeyev's dream, the irrepressible momentum of multiplicity and the

endless proliferation of bodies and selves that can no longer be apprehended or counted, but can only be

sensed in the dissolution of every singularity, ultimately his own: The wolf, as the instantaneous apprehension

of a multiplicity in a given region, is not a representative, a substitute, but an I feel. l feel myself becoming

a wolf, one wolf among others, on the edge of a pack."

14

The symbolic value of the wolf as a predatory and

threatening fgure, a castrating father, for example, is a ruse of the dreamwork, meant only as a distraction.

The true purpose of the dream is to shatter the individual and to liberate him, Pankeyev from the torment that

one lone wolf inficts upon him. His release is in the multiplicity of wolves that allows everything to reverse

itself, the wolf and me, motionlessness and violent motion, intrigue and panic. The wolf, wolves," they say,

are intensities, speeds, temperatures, nondecomposable variable distances. A swarming, a wolfing."

15

One wolf torments me, but in the eyes of many wolves, l rediscover my desire and it no longer frightens me.

The law of wolves, not of the wolf. Lassry's image compresses all of these intensities: mobility, perception,

and multiplicity. But nothing remains compressed, suppressed, or repressed, and the brief tremor of eyes

and legs unleashes the intensity deeper and deeper outward until l see myself seeing, ecstatically. Lassry

releases this fow, and before his Wolf (Blue) l am free, freer, no longer only me, a lone wolf.

1| Elad Lassry, email to author, March 5, 2012.

2| Jacques Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, ed. Michel

Lisse, Marie-Louise Mallet, and Ginnette Michaud, trans.,

Geoffrey Bennington, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 2009j, 64.

3| Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, 79.

4| Derrida, The Beast and the Sovereign, 79.

5| ln their intervention into the Wolf-Man" saga, psychoanalysts

Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok claim that neither Freud nor

any other analyst could ever have cracked the code of Pankeyev's

neurosis because it circulated through a secret language formed

between his native Russian, his adopted German, and his secret

childhood language, English. They call this secret language of

wolves a cryptonymy." Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok, The

Wolf Mans Magic Word: A Cryptonymy, trans. Nicholas Rand

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986j.

6| This book, which carries the subtitle The Double Story of

Freud's Most Famous Case," is edited by American psychoanalyst

Muriel Gardiner, one of the last to interact extensively with

Pankeyev, and includes Freud's case study From the History of an

lnfantile Neurosis," American psychoanalyst Ruth Mack Ginsberg's

writings on her experiences with the Wolf-Man, Pankeyev's

autobiography and refections on Freud, and a Foreword" by

Freud's daughter and psychoanalyst, Anna Freud. Among the

many compelling insights offered by Pankeyev is the strange claim

regarding his infantile hair color: From hearsay l know that l had,

as an infant, Titian-red hair. After my frst haircut, however, my

hair turned dark brown, something my mother deeply regretted.

She kept a little lock of the cut-off Titian-red hair, as a sort of

'relic' her entire life" (The Wolf-Man by the Wolf-Man: The Double

Story of Freuds Most Famous Case, ed. Muriel Gardiner [New

York: Basic Books, 1971|, 5j. The questionable physiognomics of

Pankeyev's account aside, this imaginary red hair is remarkable

for its over-determination: associated with the renowned colorist

Titian, his lost red hair also appears to anticipate future scenes

of castration as well as his mother's premature mourning for her

son, mummifed like Hitchcock's Psycho (1960j in reverse, in the

preserved lock of excremental hair.

7| Sigmund Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis,"

in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of

Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey, vol. Xvll (London:

Hogarth Press and the lnstitute of Psycho-Analysis, 1955j, 29,

original emphases. A nice touch in Freud's transcription of the

dream is the visual transition from the dream to its narration,

marked by the end of italics, I screamed and woke up." The

scream remains inside the dream, or on its threshold, while waking

up is already on the outside.

8| Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis," SE: XVII, 29.

9| Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis," SE: XVII, 37.

The translator translates Freud's Latin in brackets, a tergo [from

behind|."

10| Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis," SE: XVII, 34.

11| Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis," SE: XVII, 34-5.

12| Freud, From the History of an lnfantile Neurosis," SE: XVII, 35.

13| Elsewhere, Lassry speaks of white dogs, specifcally the racist

color-conscious white dog of Samuel Fuller's White Dog (1982j.

See Lassry's discussion of Fuller's white supremacist dog and

other animals in flm and art, Animalize," in Contra Mundum l-vll

(Santa Monica, CA: Oslo Editions, 2010j, 69-88.

14| Gilles Deleuze and Flix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus:

Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1987j, 32.

15| Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 32.

You might also like

- Clock of Destiny Book-1Document46 pagesClock of Destiny Book-1Bass Mcm87% (15)

- The Art of The Good Dinosaur PDFDocument171 pagesThe Art of The Good Dinosaur PDFGil Cartunista100% (1)

- Libel Arraignment Pre Trial TranscriptDocument13 pagesLibel Arraignment Pre Trial TranscriptAnne Laraga LuansingNo ratings yet

- Optical IllusionsDocument50 pagesOptical IllusionsAbishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Wolf Spirit Animal - LonerWolfDocument9 pagesWolf Spirit Animal - LonerWolfDebrup Simongreyman Roy ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- SerpentineDocument200 pagesSerpentineSerban Gabriel100% (1)

- Management of StutteringDocument182 pagesManagement of Stutteringpappu713100% (2)

- The Jaguar EuDocument13 pagesThe Jaguar EuMohiuddin JewelNo ratings yet

- LCP-027 VectraLCPDesignGuideTG AM 0613Document80 pagesLCP-027 VectraLCPDesignGuideTG AM 0613Evert100% (1)

- Smashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)Document371 pagesSmashing HTML5 (Smashing Magazine Book Series)tommannanchery211No ratings yet

- Epiphanies in DublinersDocument7 pagesEpiphanies in DublinersRafael Nallip CuelloNo ratings yet

- Stream of ConsciousnessDocument5 pagesStream of Consciousnessramiii17100% (2)

- B1 Editable End-of-Year TestDocument6 pagesB1 Editable End-of-Year TestSyahira Mayadi50% (2)

- Robert Egby - DecreesDocument9 pagesRobert Egby - DecreesmuzickaueNo ratings yet

- HAI ROBOTICS Introduction ENV2022.0829 MarketingDocument40 pagesHAI ROBOTICS Introduction ENV2022.0829 MarketingKit WooNo ratings yet

- Purchasing and Supply Chain Management (The Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin Series in Operations and Decision)Document14 pagesPurchasing and Supply Chain Management (The Mcgraw-Hill/Irwin Series in Operations and Decision)Abd ZouhierNo ratings yet

- Ted HughesDocument12 pagesTed HughesmusashisdNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KORELASI ANTARA STATUS GIZI IBU MENYUSUI DENGAN KECUKUPAN ASIDocument9 pagesJurnal KORELASI ANTARA STATUS GIZI IBU MENYUSUI DENGAN KECUKUPAN ASIMarsaidNo ratings yet

- IRJ November 2021Document44 pagesIRJ November 2021sigma gaya100% (1)

- Joe Smiths Final ThesisDocument19 pagesJoe Smiths Final Thesisapi-400868426No ratings yet

- A Tiger in The Zoo Notes 2022Document9 pagesA Tiger in The Zoo Notes 2022Tathagat SNo ratings yet

- 2) The JaguarDocument5 pages2) The JaguarAik AwaazNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument3 pagesUntitled DocumentRehaanNo ratings yet

- Liotar Lectures D'enfance TranslationDocument42 pagesLiotar Lectures D'enfance TranslationvladaalisterNo ratings yet

- The Hounf of Fate in Madame BovaryDocument9 pagesThe Hounf of Fate in Madame BovaryAlberto MarfiNo ratings yet

- BOIS, Yve-Alain - Matisse's Bathers With A TurtleDocument13 pagesBOIS, Yve-Alain - Matisse's Bathers With A TurtleIlê SartuziNo ratings yet

- Anathema: Kicking A Dead HorseDocument11 pagesAnathema: Kicking A Dead HorseEmanuel Rodriguez-ChavesNo ratings yet

- MR Mole Im Home PDFDocument1 pageMR Mole Im Home PDFSabrina Sintes SerraNo ratings yet

- Animation in Palaeolithic Art A Preecho of Cinema PDFDocument9 pagesAnimation in Palaeolithic Art A Preecho of Cinema PDFVíctor MoleroNo ratings yet

- Episode 20 - Four Reasons Why Mini-Stories Are Great For Learning EnglishDocument6 pagesEpisode 20 - Four Reasons Why Mini-Stories Are Great For Learning Englishmichalturek1983No ratings yet

- The Explanation of The Poem WolfDocument5 pagesThe Explanation of The Poem Wolfhemanta saikia100% (1)

- كتاب شعر أولى أداب أنجليزى تقليدىDocument136 pagesكتاب شعر أولى أداب أنجليزى تقليدىIsra SayedNo ratings yet

- Strathern 1993Document10 pagesStrathern 1993Leonardo Emanuel GRANÁNo ratings yet

- Narrative Cinema (1975) - Key Source Will Be Norman N. Holland's Essay Walkabout and Uses of Meat in WalkaboutDocument5 pagesNarrative Cinema (1975) - Key Source Will Be Norman N. Holland's Essay Walkabout and Uses of Meat in WalkaboutVincentNo ratings yet

- Why Does A Zebra Have Stripes?: (Maybe This Is The Wrong Question)Document7 pagesWhy Does A Zebra Have Stripes?: (Maybe This Is The Wrong Question)AnnaNo ratings yet

- Lippit OectopusDocument6 pagesLippit OectopusEuJin ChuaNo ratings yet

- Danielle VCDB 4Document2 pagesDanielle VCDB 4api-490069890No ratings yet

- Werewolf ThesisDocument9 pagesWerewolf Thesisbsnj6chr100% (2)

- Language of Eveline LITERATUREDocument2 pagesLanguage of Eveline LITERATUREMeriem TigrieneNo ratings yet

- Kingsley 1973Document10 pagesKingsley 1973harris helenaNo ratings yet

- O Dieses Ist Das Tier, Das Es Nicht Gibt': Rilke and UnicornsDocument11 pagesO Dieses Ist Das Tier, Das Es Nicht Gibt': Rilke and UnicornsCarlos Alberto SanchesNo ratings yet

- Orwell A Hanging - Close ReadingDocument10 pagesOrwell A Hanging - Close ReadingMartyna Biorka (SMA Teacher)No ratings yet

- JabberwockyDocument38 pagesJabberwockyKenneth Arvin Tabios100% (1)

- English 5 Week 2Document83 pagesEnglish 5 Week 2Mary Grace AlmonteNo ratings yet

- God Tries To Teach Crow To Say LOVE: Crow Gaped, and The White Shark Crashed Into The Sea'. (Crow's First Lesson)Document4 pagesGod Tries To Teach Crow To Say LOVE: Crow Gaped, and The White Shark Crashed Into The Sea'. (Crow's First Lesson)Vic HugoNo ratings yet

- The Loaded Dog ScaffoldDocument3 pagesThe Loaded Dog Scaffoldmahip7506100% (1)

- Salvador Dali Paintings MeaningDocument4 pagesSalvador Dali Paintings MeaningAnindhita Irsalina WNo ratings yet

- A Tiger in The ZooDocument4 pagesA Tiger in The ZooManya SinghNo ratings yet

- Animal Imagery - LectureDocument6 pagesAnimal Imagery - LectureStuart HendersonNo ratings yet

- The Significance of Some Behaviour Patterns of PigeonsDocument14 pagesThe Significance of Some Behaviour Patterns of PigeonsRabia QayyumNo ratings yet

- OliverLaufenberg HOPR1955 WilliamWilsonResponse PratchettsGalleryDocument2 pagesOliverLaufenberg HOPR1955 WilliamWilsonResponse PratchettsGalleryAwesomefettNo ratings yet

- The Rabbits Who Caused All The TroubleDocument5 pagesThe Rabbits Who Caused All The Troubledidon2950% (2)

- From Aesop To ReynardDocument128 pagesFrom Aesop To ReynardMarcela RistortoNo ratings yet

- Poem - 3 - A - Tiger - in - The - Zoo First - FlightDocument4 pagesPoem - 3 - A - Tiger - in - The - Zoo First - FlightChirag WNo ratings yet

- Youth NonfictionDocument9 pagesYouth Nonfictionapi-360646193No ratings yet

- Seminar 2 Phonetic and Graphic Means of Stylistics: ExercisesDocument8 pagesSeminar 2 Phonetic and Graphic Means of Stylistics: ExercisesКарина ГладырьNo ratings yet

- PDF Animals AnalysisDocument13 pagesPDF Animals AnalysisJona ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Brief Comments On Eszter TarisDocument12 pagesBrief Comments On Eszter TarisGabor KovacsNo ratings yet

- Argos Vs Cyclops: Argus Panoptes (All-seeing) (Ancient Greek: Ἄργος Πανόπτης) or Argos (Ancient Greek: Ἄργος) is a manyDocument5 pagesArgos Vs Cyclops: Argus Panoptes (All-seeing) (Ancient Greek: Ἄργος Πανόπτης) or Argos (Ancient Greek: Ἄργος) is a manyLavenzel YbanezNo ratings yet

- C It As Bergery ElinDocument2 pagesC It As Bergery ElinPilar CimadevillaNo ratings yet

- Correspondence Carr Honeit 2Document3 pagesCorrespondence Carr Honeit 2Allie CarrNo ratings yet

- JawsDocument4 pagesJawsHmilliner220% (1)

- Culture, Symbol and LanguajeDocument41 pagesCulture, Symbol and LanguajeJean Paul CastroNo ratings yet

- Promenade 2005 ArtpressDocument3 pagesPromenade 2005 Artpressst_jovNo ratings yet

- The Jaguar ExemplarDocument2 pagesThe Jaguar ExemplarShriya JagwayanNo ratings yet

- Tentang Wayang KulitDocument4 pagesTentang Wayang KulitTeguh KiyatnoNo ratings yet

- Animals and The Concept of DignityDocument24 pagesAnimals and The Concept of DignityDevynNo ratings yet

- Living Like A Weasel ThesisDocument4 pagesLiving Like A Weasel Thesisbethhernandezpeoria100% (2)

- Hill PDFDocument15 pagesHill PDFdaugschoNo ratings yet

- Pedro Alfacinha LisboaDocument3 pagesPedro Alfacinha LisboadaugschoNo ratings yet

- Case : The "OfDocument7 pagesCase : The "OfdaugschoNo ratings yet

- In Deed: Certificates of Authenticity in Art: November 3-December 9, 2012Document5 pagesIn Deed: Certificates of Authenticity in Art: November 3-December 9, 2012daugscho100% (1)

- Clean Constructed: PlanetaDocument5 pagesClean Constructed: PlanetadaugschoNo ratings yet

- A Note On The TypeDocument14 pagesA Note On The TypedaugschoNo ratings yet

- Vision Justice WEB 1.2 Spreads PDFDocument41 pagesVision Justice WEB 1.2 Spreads PDFXimenaNo ratings yet

- Lewitt, 45 Exhibition CardsDocument45 pagesLewitt, 45 Exhibition CardsdaugschoNo ratings yet

- Backstory: Latoya Ruby Frazier Ron Jude Guillaume SimoneauDocument4 pagesBackstory: Latoya Ruby Frazier Ron Jude Guillaume SimoneaudaugschoNo ratings yet

- Sebald Rings PDFDocument15 pagesSebald Rings PDFdaugschoNo ratings yet

- De Chirico in EnglishDocument57 pagesDe Chirico in EnglishnickNo ratings yet

- Falschungserschwerende SchriftDocument7 pagesFalschungserschwerende SchriftdaugschoNo ratings yet

- Agile in ISO 9001 - How To Integrate Agile Processes Into Your Quality Management System-Springer (2023)Document67 pagesAgile in ISO 9001 - How To Integrate Agile Processes Into Your Quality Management System-Springer (2023)j.paulo.mcNo ratings yet

- PUBLIC - Axie Origins Changelogs - Season 4Document2 pagesPUBLIC - Axie Origins Changelogs - Season 4Alef CarlosNo ratings yet

- New KitDocument195 pagesNew KitRamu BhandariNo ratings yet

- Excel Lesson 5 QuizDocument5 pagesExcel Lesson 5 Quizdeep72No ratings yet

- Color Coding Chart - AHGDocument3 pagesColor Coding Chart - AHGahmedNo ratings yet

- Gender and Patriarchy: Crisis, Negotiation and Development of Identity in Mahesh Dattani'S Selected PlaysDocument6 pagesGender and Patriarchy: Crisis, Negotiation and Development of Identity in Mahesh Dattani'S Selected Playsতন্ময়No ratings yet

- Python Programming Laboratory Manual & Record: Assistant Professor Maya Group of Colleges DehradunDocument32 pagesPython Programming Laboratory Manual & Record: Assistant Professor Maya Group of Colleges DehradunKingsterz gamingNo ratings yet

- High Intermediate 2 Workbook AnswerDocument23 pagesHigh Intermediate 2 Workbook AnswernikwNo ratings yet

- HW Chapter 25 Giancoli Physics - SolutionsDocument8 pagesHW Chapter 25 Giancoli Physics - SolutionsBecky DominguezNo ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument14 pagesData SheetAnonymous R8ZXABkNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan Nokia - Advanced MarketingDocument8 pagesMarketing Plan Nokia - Advanced MarketingAnoop KeshariNo ratings yet

- Feature Glance - How To Differentiate HoVPN and H-VPNDocument1 pageFeature Glance - How To Differentiate HoVPN and H-VPNKroco gameNo ratings yet

- Vicente BSC2-4 WhoamiDocument3 pagesVicente BSC2-4 WhoamiVethinaVirayNo ratings yet

- EffectivenessDocument13 pagesEffectivenessPhillip MendozaNo ratings yet

- Venere Jeanne Kaufman: July 6 1947 November 5 2011Document7 pagesVenere Jeanne Kaufman: July 6 1947 November 5 2011eastendedgeNo ratings yet

- SSC 211 ED Activity 4.1Document4 pagesSSC 211 ED Activity 4.1bernard bulloNo ratings yet

- Week1 TutorialsDocument1 pageWeek1 TutorialsAhmet Bahadır ŞimşekNo ratings yet

- First Aid Transportation of The InjuredDocument30 pagesFirst Aid Transportation of The InjuredMuhammad Naveed Akhtar100% (1)

- INDUSTRIAL PHD POSITION - Sensor Fusion Enabled Indoor PositioningDocument8 pagesINDUSTRIAL PHD POSITION - Sensor Fusion Enabled Indoor Positioningzeeshan ahmedNo ratings yet