Professional Documents

Culture Documents

High Frequency Trading Chicago Fed October2012 303

Uploaded by

oak7230 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views4 pagesHigh Frequency Trading

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHigh Frequency Trading

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views4 pagesHigh Frequency Trading Chicago Fed October2012 303

Uploaded by

oak723High Frequency Trading

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

How to keep markets safe in the era of high-speed trading

by Carol Clark, senior policy specialist

A number of recent technology-related snafus have focused attention on high-speed

trading and affected investor confidence in the markets. These incidents and the resulting

losses highlight the need for risk controls at every step of the trading process.

On Wednesday, August 1, 2012, a $440 mil-

lion loss in 45 minutes brought market

maker Knight Capital to the brink of

bankruptcy. The loss was caused by a

software malfunction that resulted in

Knight sending a

large number of or-

ders to the New York

Stock Exchange.

1

For

a time following the

mishap, three of its

online retail broker-

age clientsTD

Ameritrade, Scottrade,

and E*Trade

stopped routing

trades to Knight.

2

In May 2012, just three

months before the

Knight Capital deba-

cle, a technical error

at NASDAQ delayed

the start of trading for

Facebooks initial pub-

lic offering (IPO) and

prevented some in-

vestors from learning

whether they had

successfully purchased

or sold shares. This prompted some of

them to enter orders numerous times and

led to uncertainty about their overall

positions in the market. As a result of the

error, the Swiss bank UBS is said to have

suffered a loss of more than $350 million.

Knight Capital reportedly lost $35.4 mil-

lion in the Facebook incident as well.

3

The nations third-largest stock exchange,

BATS, withdrew its IPO in March of this

year, following a software glitch that

also caused a 9% decline in the price

of Apple shares and paused the buying

and selling of Apple for fve minutes.

4

The extent of these losses and the fre-

quency with which these incidents are

occurring in seemingly well-managed

frms is focusing attention on the need

for risk controls at every level of the

trade life cycle, i.e., at trading frms,

brokerdealers (BDs), futures commis-

sion merchants (FCMs), exchanges,

and clearinghouses.

Industry and regulatory groups have

articulated best practices related to risk

controls, but many frms fail to imple-

ment all the recommendations or rely

on other frms in the trade cycle to catch

an out-of-control algorithm or erroneous

trade. In part, this is because applying

risk controls before the start of a trade

can slow down an order, and high-speed

trading frms are often under enormous

pressure to route their orders to the

exchange quickly so as to capture a

trade at the desired price.

The competition for speed also affects

BDs/FCMs. Some tout how quickly they

can check customer orders before send-

ing them to the exchange. The risk is

that some BDs/FCMs may establish less

stringent pre-trade risk controls to accel-

erate order submission. Other BDs/FCMs

rely solely on the pre-trade risk checks

Chicag o Fed Letter

ESSAYS ON ISSUES THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OCTOBER 2012

OF CHICAGO NUMBER 303

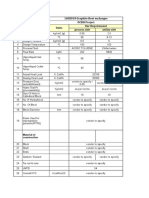

1. High-speed trading by asset class

NOTE: Data for 2012 are estimates.

SOURCE: Aite Group, also featured in Financial Stability Oversight Council, 2012

Annual Report, available at www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/Documents/

2012%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

percent

2008 2009 2010 2011 e2012

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

U.S. equities

Global futures

Global FX

Global fixed income

at exchanges rather than implement-

ing their own risk controls. The prob-

lem with this approach is that some

exchanges risk controls might be

structured in a way that does not stop

erroneous orders before they are flled.

Once orders are matched in the match-

ing engine, exchanges send drop copies

(information on flled trades) to trading

frms and clearing BDs/FCMs to help

them manage their exposures. Some ex-

changes also provide information on

orders that are still working in the mar-

ket in their drop copies. Of critical im-

portance in the management of risk is

the time frame in which trading frms

and BDs/FCMs receive these post-trade

data. While some exchanges send drop

copy in near real time (microseconds),

others provide it within hours, or at the

end of the trading day. Delays in receiving

post-trade data hinder optimal risk man-

agement at trading frms and BDs/FCMs.

Another potential risk management

issue relates to how some high-speed

trading frms have equity ownership

stakes in certain exchanges. An open

question is whether these ownership

stakes allow them to infuence the struc-

ture of the exchanges systems to the

advantage of high-speed trading frms

but to the detriment of optimal risk man-

agement. An alternative possibility is

whether these frms familiarity with the

risks of high-speed trading causes them

to infuence the adoption of more strin-

gent risk controls at the exchange level.

It is a given that technological advances

are here to stay, that high-speed trading

is increasing in most markets (see fg-

ure 1), and that reverting to traditional,

open outcry trading is not an option.

The question then is how to keep mar-

kets safe in a highly technological envi-

ronment. Until about a decade ago, most

exchange-traded instruments in the U.S.

were traded in a physical, paper-based

environment. Orders were called in by

telephone, transcribed by humans and

passed on to others for execution, con-

frmation, and settlement. During each

step, a person would look at the order

and, knowing where the market was

trading, make a value judgment as to

whether a clerical error might have

been made. Certainly, errors still occurred,

but ample opportunities existed to detect

and correct them. High-speed trading

requires a similar level of monitoring,

but it needs to happen a lot faster

ideally, there should be automated risk

controls at every step in the life cycle of

a trade with human beings overseeing

the process.

To understand better the controls cur-

rently used by market participants, re-

searchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of

Chicago interviewed more than 30 tech-

nology vendors, clearing BDs/FCMs,

5

representatives of proprietary trading

frms, futures commission merchants,

and exchange and clearinghouse pro-

fessionals.

6

In the remainder of this

Chicago Fed Letter, I provide an overview

of this research on the current risk-

control landscape and identify potential

improvements in risk-control practices.

In todays environment, how are risks

managed before a trade is executed?

There are multiple points in the life

cycle of a trade where orders may be

checked against pre-set limits before

they reach the exchange matching

engine. These checks may occur at the

trading frm, clearing BD/FCM, and/

or exchange.

7

Risk controls at clearing BDs/FCMs

Clearing BDs/FCMs are fnancially re-

sponsible for their own trades and for the

trades of their customers. Some of these

customers send orders to an exchange

using trading systems that the clearing

BD/FCM provides or that are offered by

a vendor the clearing BD/FCM approves.

BDs/FCMs also build or buy trading

platforms to route their own proprietary

orders to exchanges. In order to control

the amount of possible losses that may

arise from its own trading activity as well

as that of its customers, the clearing

BD/FCM typically establishes risk limits

on these trading systems. Some exchanges

also provide functionality to clearing

BDs/FCMs to set risk limits on the ex-

change server. This functionality may be

mandatory or optional or may not be

offered at all, depending on the exchange.

Other customers of clearing BDs/FCMs

may send their orders directly to the

exchange through trading systems they

build themselves. Clearing BDs/FCMs

manage the risks of customers that access

the markets directly in one or more of

the following ways:

By remotely accessing the customers

server(s) at the co-location facility and

checking whether the customer has

established risk limits on the server(s).

By setting risk limits on the clearing

BD/FCMs server(s) at the co-location

facility and requiring customers to

connect to its server(s).

By using functionality provided by the

exchange that enables them to set

risk limits on the exchange server.

By relying on risk checks set by ex-

change staff on the exchange server.

Risk controls at trading firms that

access the markets directly

Risk managers at trading frms that access

the markets directly may set their own

risk limits by:

Establishing risk limits on their own

trading servers; and/or

Using functionality provided by the

exchange(s) that enables them to set

risk limits on the exchange server.

Again, this functionality may be manda-

tory or optional or may not be offered

at all, depending on the exchange.

Individual traders and/or trading groups

at trading frms may set risk limits, under

the levels established by the trading frms

risk manager, on their client systems,

or on the graphical user interfaces.

Over the past several years, reports have

circulated that some BDs/FCMs may

not have been properly controlling the

risks associated with their customers

direct access to the markets. In particular,

concerns were raised that some BDs/

FCMs were allowing these customers to

send their orders to an exchange without

establishing adequate pre-trade limits

on their trading platforms, thereby ex-

posing the BDs/FCMs to fnancial risk.

To ensure that BDs/FCMs are appropri-

ately managing the risks of customers

that access the markets directly, the

Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC) implemented Rule 15c3-5 in

July 2011, which, among other things,

requires BDs to maintain a system of

controls and supervisory procedures

reasonably designed to limit the fnancial

exposures arising from customers that

access the markets directly.

8

The U.S.

Commodity Futures Trading Commission

(CFTC) also adopted rules in April 2012

to bolster risk management at the

FCM level.

9

Risk controls at exchanges

Exchanges, too, may establish pre-trade

risk checks on their own servers. Auto-

mated systems compare all orders/

quotes against these pre-established

limits before they reach the matching

engine. Exchanges that impose pre-trade

risk checks increase latencythe time

it takes to send an order to an exchange

and receive an acknowledgment of the

order from the exchangeequitably and

uniformly for all market participants on

that exchange. Nevertheless, the num-

ber of pre-trade risk checks individual

exchanges employ and the time it takes

to execute them vary by exchange.

Study findings

To summarize, when an order is origi-

nated, it may get checked against risk

limits set at the trading frm, clearing

BD/FCM, and exchange before it reaches

the exchange matching engine. With

the chance of an order passing though

controls at so many levels, how can things

go wrong? One possibility Chicago Fed

researchers found is that most of the

trading frms interviewed that build their

own trading systems apply fewer pre-trade

checks to some trading strategies than

others. Trading frms explained that

they do this in order to reduce latency.

Another area of concern is that some

frms do not have stringent processes for

the development, testing, and deploy-

ment of code used in their trading algo-

rithms. For example, a few trading frms

interviewed said they deploy new trading

strategies quickly by tweaking old code

and placing it into production in a matter

of minutes. In fact, one frm interviewed

had two incidents of out-of-control al-

gorithms. To address the frst occurrence,

the frm added additional pre-trade

risk checks. The second out-of-control

algorithm was caused by a software bug

that was introduced as a result of some-

one fxing the error code that caused

the frst situation.

The study also found that erroneous

orders may not be stopped by some

clearing BDs/FCMs because they are

relying solely on risk controls set by the

exchange. As noted earlier, however,

risk controls at the exchange may be

structured in such a way that they do

not stop all erroneous orders.

Chicago Fed staff also found that out-of-

control algorithms were more common

than anticipated prior to the study and

that there were no clear patterns as to

their cause. Two of the four clearing

BDs/FCMs, two-thirds of proprietary

trading frms, and every exchange inter-

viewed had experienced one or more

errant algorithms. The frequency with

which they occur varies by exchange.

One exchange said it could detect an out-

of-control algorithm if it had a signifcant

price impact, but not if an algorithm

slowly added up positions over time,

although exchange staff had heard of

such occurrences.

The study also revealed that there may

be times when no single entity in the

trade life cycletrading frm, clearing

BD/FCM, exchange, or clearinghouse

has a complete picture of a frms ex-

posures across markets. For example,

some trading frms and BDs/FCMs are

unable to calculate their enterprise-wide

portfolio risk. Trading frms and BDs/

FCMs need to aggregate trade informa-

tion from multiple exchanges in a central

repository and calculate their overall

exposures in the markets in a timely

manner. However, the speed at which

this calculation can be made depends

on how quickly trading frms and BDs/

FCMs receive drop copy information

from exchanges. Some trading frms also

use multiple BDs/FCMs to clear trades,

which results in no single BD/FCM being

able to see the trading frms exposures

across markets. Many trading frms also

trade at multiple exchanges, and trades

are settled at multiple clearinghouses.

This prevents any single exchange or

clearinghouse from seeing the total

positions amassed by the frm.

Interestingly, market participants at every

level of the trade life cycle reported they

are looking to regulators to establish best

practices in risk management and to

monitor compliance with those practices.

Mitigating risks

What are some controls that might have

helped to mitigate the recent losses re-

lated to high-speed trading? In the case

of Knight Capital, the following are some

examples of controls at the trading frm

and clearing BD level that might have

aided in containing the fnancial loss:

Limits on the number of orders that

can be sent to an exchange within a

specifed period of time;

A kill switch that could stop trading

at one or more levels;

Intraday position limits that set the

maximum position a frm can take

during one day;

Proft-and-loss limits that restrict the

dollar value that can be lost.

In addition, trading frms should have

access controls defning who can develop,

test, modify, and place an algorithm into

production, as well as quality assurance

Charles L. Evans, President ; Daniel G. Sullivan,

Executive Vice President and Director of Research;

Spencer Krane, Senior Vice President and Economic

Advisor ; David Marshall, Senior Vice President, fnancial

markets group ; Daniel Aaronson, Vice President,

microeconomic policy research; Jonas D. M. Fisher,

Vice President, macroeconomic policy research; Richard

Heckinger,Vice President, markets team; Anna L.

Paulson, Vice President, fnance team; William A. Testa,

Vice President, regional programs, and Economics Editor ;

Helen OD. Koshy and Han Y. Choi, Editors ;

Rita Molloy and Julia Baker, Production Editors ;

Sheila A. Mangler, Editorial Assistant.

Chicago Fed Letter is published by the Economic

Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank

of Chicago. The views expressed are the authors

and do not necessarily refect the views of the

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal

Reserve System.

2012 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Chicago Fed Letter articles may be reproduced in

whole or in part, provided the articles are not

reproduced or distributed for commercial gain

and provided the source is appropriately credited.

Prior written permission must be obtained for

any other reproduction, distribution, republica-

tion, or creation of derivative works of Chicago Fed

Letter articles. To request permission, please contact

Helen Koshy, senior editor, at 312-322-5830 or

email Helen.Koshy@chi.frb.org. Chicago Fed

Letter and other Bank publications are available

at www.chicagofed.org.

ISSN 0895-0164

procedures for the code and development

processes. Clearing BDs/FCMs should

periodically audit these access controls

and quality assurance procedures.

The BATS and Facebook IPOs would also

likely have benefted from more strin-

gent development and testing controls

at the exchange level. The manner in

which exchange policies were invoked

during the two IPOs and in the Knight

Capital incident also added to uncertainty

in the marketplace. Specifcally, market

participants need to know whether their

trades are being adjusted or busted (in-

validated) in the shortest possible time.

These are only a few of the practices that

could potentially help to control erro-

neous trades in a high-speed trading

environment. Each level of the trade life

cycle should also have a risk manager

who can respond quickly if exposures

exceed pre-set limits. More generally,

regulators should work with the industry

to defne best practices and to audit

frms compliance with them. At the very

minimum, it is critically important that

each frm involved in the life cycle of a

high-speed trade has its own risk con-

trols and does not rely solely on anoth-

er frm in the cycle to manage its risk.

To that end, the Financial Stability

Oversight Council (FSOC), a council

of regulators established under the

DoddFrank Act, recommended in

July 2012 that the SEC and the CFTC

consider establishing error control and

standards for exchanges, clearinghouses,

and other market participants that are

relevant to high-speed trading.

10

1 See http://dealbook.nytimes.com/

2012/08/02/knight-capital-says-trading-

mishap-cost-it-440-million/; and http://

dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/08/02/

trying-to-be-nimble-knight-capital-stumbles.

2 See www.advancedtrading.com/

managingthedesk/240004887.

3 See http://newsandinsight.

thomsonreuters.com/Securities/

News/2012/08_-_August/Citadel_urges_

SEC_to_approve_Nasdaq_s_Facebook_

compensation_plan/.

4

See www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-25/

bats-ceo-scuttled-ipo-on-potential-for-

erratic-trading.html.

5

Clearing BDs/FCMs are members of an

exchange clearinghouse, where trades

are settled.

6

For detailed fndings of the study, see

www.chicagofed.org/webpages/

publications/publications_listing.

cfm?flter_series=16.

7

A visual representation of the trade life cy-

cle and risk controls is available at http://

chicagofed.org//digital_assets/others/

markets/trading_infrastructure_graphic.pdf.

8

See www.sec.gov/rules/fnal/2010/

34-63241.pdf.

9

See www.cftc.gov/ucm/groups/public/

@lrfederalregister/documents/fle/

2012-7477a.pdf.

10

See www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/

Documents/2012%20Annual%20

Report%20Recommendations.pdf.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cass Sunstein - Conspiracy TheoriesDocument30 pagesCass Sunstein - Conspiracy TheoriesBalthazar PicsouNo ratings yet

- Dope Inc Update-Eirv36n08Document76 pagesDope Inc Update-Eirv36n08oak723100% (1)

- Dope Inc Update-Eirv36n08Document76 pagesDope Inc Update-Eirv36n08oak723100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- EL CID Stator Core TestDocument2 pagesEL CID Stator Core TestAnonymous CO7aaHrNo ratings yet

- ASTM Pumping TestDocument125 pagesASTM Pumping TestErnesto Heinze100% (1)

- Asme b16.5Document246 pagesAsme b16.5hugo_siqueira_11No ratings yet

- Managerial Communication - (MC) - SEM I-GTUDocument93 pagesManagerial Communication - (MC) - SEM I-GTUkeyurNo ratings yet

- Tappi 0502-17 Papermaker FormulaDocument19 pagesTappi 0502-17 Papermaker FormulaMulyadi Moel86% (21)

- Válečná Historie Bank of England (Úryvek)Document10 pagesVálečná Historie Bank of England (Úryvek)Euro.czNo ratings yet

- Derivatives CityUK 2012Document16 pagesDerivatives CityUK 2012oak723No ratings yet

- Biggest Swindle Ever PulledDocument2 pagesBiggest Swindle Ever Pulledoak723No ratings yet

- European Banking ClubsDocument14 pagesEuropean Banking Clubsoak723No ratings yet

- BHTM445 Syllabus MW - Spring 2015-2016Document6 pagesBHTM445 Syllabus MW - Spring 2015-2016dangerousbabyNo ratings yet

- 009-1137-00 HST-SMRTD Savant Smart Host Tech SpecDocument6 pages009-1137-00 HST-SMRTD Savant Smart Host Tech Specferna2420No ratings yet

- Safety Integrity Level (SIL) Determination Using LOPA Methods To Comply With IEC 61511 and ISA 84Document3 pagesSafety Integrity Level (SIL) Determination Using LOPA Methods To Comply With IEC 61511 and ISA 84naren_013No ratings yet

- Est-Pergola Octogonal 21-03-2022Document1 pageEst-Pergola Octogonal 21-03-2022Victor MuñozNo ratings yet

- Cu Ext 2015Document4 pagesCu Ext 2015mohammedzuluNo ratings yet

- Contoh Ringkasan Mengajar Bahasa Inggeris Tahun 2 Dan 3Document2 pagesContoh Ringkasan Mengajar Bahasa Inggeris Tahun 2 Dan 3Izla MajidNo ratings yet

- Plasma TV SMPS TroubleshoutingDocument5 pagesPlasma TV SMPS TroubleshoutingmindjokerNo ratings yet

- IOT SyllabusDocument3 pagesIOT Syllabuspoojan thakkarNo ratings yet

- Iare WCN Tutorial Question BankDocument7 pagesIare WCN Tutorial Question BankVigneshNo ratings yet

- Negative Skin Friction Aaron Budge Minnesota State UniversityDocument46 pagesNegative Skin Friction Aaron Budge Minnesota State UniversityNguyễn Thành NhânNo ratings yet

- Giving Constructive Feedback Training Course OutlineDocument3 pagesGiving Constructive Feedback Training Course OutlineJeeNo ratings yet

- BSBPMG531 - Assessment Task 3 v2Document19 pagesBSBPMG531 - Assessment Task 3 v2Felipe ParadaNo ratings yet

- 816D Specalog (Small)Document2 pages816D Specalog (Small)Arvind HarryNo ratings yet

- Dometic RM4185 6405 PDFDocument20 pagesDometic RM4185 6405 PDFcarlosrei2No ratings yet

- Materi 1 - Analisis SinyalDocument17 pagesMateri 1 - Analisis SinyalUsmanNo ratings yet

- Evs Unit 3 (2020)Document16 pagesEvs Unit 3 (2020)Testing FunNo ratings yet

- Pumps: Vane Type Single PumpsDocument2 pagesPumps: Vane Type Single PumpsFernando SabinoNo ratings yet

- 16HE018 Graphite Heat Exchanger DCBH Project Sr. No. Particulars Units Our Requirement Process Side Utility SideDocument2 pages16HE018 Graphite Heat Exchanger DCBH Project Sr. No. Particulars Units Our Requirement Process Side Utility SideBhaumik BhuvaNo ratings yet

- Ingrid Olderock La Mujer de Los Perros by Nancy GuzmnDocument14 pagesIngrid Olderock La Mujer de Los Perros by Nancy GuzmnYuki Hotaru0% (3)

- StetindDocument6 pagesStetindGiovanniNo ratings yet

- NTS - Math Notes & Mcqs Solved Grade 8thDocument10 pagesNTS - Math Notes & Mcqs Solved Grade 8thZahid KumailNo ratings yet

- 3 Africacert Project PublicDocument15 pages3 Africacert Project PublicLaïcana CoulibalyNo ratings yet

- PowerMaxExpress V17 Eng User Guide D-303974 PDFDocument38 pagesPowerMaxExpress V17 Eng User Guide D-303974 PDFSretenNo ratings yet

- Lowry Hill East Residential Historic DistrictDocument14 pagesLowry Hill East Residential Historic DistrictWedgeLIVENo ratings yet

- After12th FinalDocument114 pagesAfter12th FinaltransendenceNo ratings yet