Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Appellate Advocacy Writing Sample

Uploaded by

Christopher WilliamsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Appellate Advocacy Writing Sample

Uploaded by

Christopher WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Christopher Williams

645 E. Holly St. #204 Boise, ID83712

Email: Will8385@vandals.uidaho.edu

Tel: (509) 540-0028

WRITING SAMPLE

To whom it may concern,

Attached is a 9 page copy of the facts and analysis section of an appellate paper written

for University of Idaho Law Schools McNichols Appellate Advocacy Competition in fall 2013.

Out of approximately 30 participants, I was placed in the top 16. Althoughcritique was sparsely

offered by professors and fellow students, the work remains entirely written by me.

Thank you for reading,

Christopher Williams

2

ISSUES ON APPEAL

1. Under the free speech clause of the first amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which

allows only limited exceptions to the general rule that all speech is protected, did the

district court err by determining that the true threat exception should be measured by a

broad objective standard that makes all speech that could be interpreted as a threat

unprotectable, as opposed to a narrow subjective standard that only makes threats that the

communicator intended to be interpreted as a threat punishable.

2. [SECOND ISSUE OMITTED]

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On J anuary 30, 2013, Ms. MaryJ ane Cobbs was questioned by two prison guards, Officer

Malcom Reynolds and Officer Dobson, regarding apossibly threateningletter that Ms. Cobbs

was suspected of sending. (R. 1112). At the time of the questioningshe was a prisoner for an

unrelated incident. (R. 16:2530). She was interrogatedby the Officers for several hours in a

small room. (R. 13:11). Ms. Cobbs was not informed of her rights and made incriminating

statements after relentless questioning. (R. 14:1923).

Captain Simon Tam is a ship captain responsible for anincident which killed a whaler.

(R. 78). About a week before the interrogation, CaptainTamreceived a letter anonymously

written by Ms. Cobbsthat, in Tams words, stated the writer was going to see that [Tam] got

what [he] deserved and ended with an eye for an eye. (R. 8:19). Tam was scared by the

letter. (R. 8:22). Ms. Cobbs was attempting to express support for Tam in her letter and convey

her disdain for the whaler that died. (R. 16:1213). This is in line with her past attempts at

expressing her political opinion; one of those incidents, writing a bad check to an animal rights

organization, is the reason she was in prison during the interrogation. (R. 16:2530, 17).

[FACTS RELEVANT TO SECOND ISSUE OMITTED]

3

The district court denied the Defendants motion to suppress statements made during the

interrogation, finding instead that the Defendant was not in Miranda custody during the

interrogation, and, thus, her self-incriminating statements were admissible at trial. (R. 10). The

court also found, in contradiction with the subjective standard of true threat, that the speech in

the defendants letter wasa true threat and thus not protectable as free speech under the First

Amendment. (R. 4). The Defendant requests that the Court reverse the decision by the district

court to use an objective standard to determine whether a true threat hadbeen made, and reverse

the decision by the district court to allow Ms. Cobbs self-incriminating statements to be

presented as evidence during trial.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

The question regarding the proper construction of the word threat is a question of law

decided by the court de novo. Planned Parenthood of Columbia/Willamette, Inc. v. Am. Coal. of

Life Activists, 290 F.3d 1058, 1070 (9th Cir. 2002). [. . .]

ARGUMENT

The district court incorrectly found that an objective standard was appropriate when

determining whether the true threat exception to the Free Speech clause of the First

Amendment appliedin this case because the plain meaning of the rule endorsed by the Supreme

Court in Virginia v. Black supports a subjective test, and the subjective standard is more in line

with the long-held principles that allow exceptions to the Free Speech clause. [. . .]

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN CONCLUDING THAT AN OBJECTIVE

TEST FOR DETERMINING WHETHER A TRUE THREAT HAS BEEN MADE

WAS THE PROPER TEST BECAUSE THE NARROW EXCEPTIONS TO THE

FIRST AMENDMENT, AS WELL AS THE POLICY ARGUMENTS THAT

SUPPORT A TRUE THREAT EXCEPTION, SUPPORT A SUBJECTIVE TEST.

4

Ms. Cobbs requests that the court reverse her conviction under 18 U.S.C. 875(c)

because the district court erred when it used an objective test to determine whether her statement

constituted a true threat in contradiction with the plain meaning of the Supreme Courts rule and

the policy concerns that allow a true threat exception to the First Amendment. The law Ms.

Cobbs was convicted under makes it a criminal offense for anyone to transmit[] in interstate . . .

commerce any communication containing any threat . . . to injure the person of another. 18

U.S.C. 875(c) (1994). The statute contains no definition of the word threat. Id.

The First Amendment explicitly protects the people from the government abridging the

freedom of speech. U.S. CONST. amend. I. The Supreme Court has found that this amendment is

centralized around the idea that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-

open. Bond v. Floyd, 385 U.S. 116, 136 (1966) (quoting New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S.

254, 270 (1964)). The right to Freedom of Speech guaranteed by the First Amendment is

characterized as a fundamental personal right and liberty. Schneider v. State of New Jersey,

Town of Irvington, 308 U.S. 147, 150 (1939). When the Supreme Court refers to the right as

fundamental, the court emphasizes the importance of preventing the restriction of these

liberties. Id. at 150151. Theissue here is whether Ms. Cobbs actions fall under the

constitutional exception to the first amendment that makes a true threat unprotectable as

speech. The court should err on the side of caution and take a more narrow view of how broadly

the true threat exception extends.

The non-protection of true threatsis one of the narrowly and jealously defined exceptions

to the fundamental right to free speech. Watts v. U.S., 394 U.S. 705 (1969). There are two

approachesaccepted by the circuit courtsused to determinewhether a statement is construed as a

true threat or not. The first is a subjective approach that turns on whether the defendant intends

5

for their statement to be construed as a threat. U.S. v. Stock, 2013 WL 4504766 (3d Cir. 2013)

(We hold that the word threat in 875(c) encompasses only communications expressing an

intent to inflict injury in the present or future). The second, more broadly applicable, approach

is an objective approach that merelyrequires the government to prove a reasonable recipient

would interpret the defendants communication as a serious threat to injure. U.S. v. Nicklas, 713

F.3d 435, 440 (8th Cir. 2013). Ms. Cobbs never intended for her letter to intimidate or threaten

Tam, and, therefore, the letter was an exercise of free speech under the subjective test and is

protected. Because Ms. Cobbsspeech was protected under the subjective test, the district courts

ruling should be reversed.

A. The plain meaning of thetrue threat exceptionruleexplicitly carries an element of

intentionand thus supports the subjectivetest.

The Supreme Court statedthat True threats encompass those statements where the

speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to communicate an act of

unlawful violence to a particular individual . . .Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343(2003) (citing

Watts v. U.S. 394 U.S. 705 (1969)) (emphasis added). The definition of mean used as a verbis

1Intent to convey, indicate, or refer to (a particular thing or noun); signify . . . 2Intend

(something) to occur or be the case: they mean no harm . . . 3 Have as a consequence or result . .

. THE NEW OXFORD AMERICAN DICTIONARY Loc 580213 (3d ed. 2011) (retrieved from Kindle).

Thus where J ohn means to eat the apple pie, through the plain and ordinary meaningof means,

J ohnintends that his consumption of the apple pie is the outcome. The same is true of the issue

of true threat. Where a person means to communicate a serious threat of an act of violence, they

intend to communicatea serious threat of an act of violence.

The objective test is a gross misinterpretation of the Supreme Courts true threat rule.

The objective test espoused by some circuit courtsrequires onlythat, in order for the speech to

6

be unprotectable under the true threat doctrine, the defendant should have reasonably foreseen

that the statement he uttered would be taken as a threat by those whom it is made. U.S. v.

Whiffen, 121 F.3d 18, 21 (1st Cir. 1997) quoting U.S. v. Fulmber, 108 F.3d 1486 (1st Cir. 1997).

This broad rule flies inthe face of the Supreme Court rule that requires that the communicator

intend tocommunicate a threat of violence, completely ignoring the language of the rule

espoused.

Because the plain and ordinary meaning of the true threat rule as endorsedby the

Supreme Court requires that the communicator intend to convey a threat to the person receiving

the communication, the subjective test is more in syncwith the language of the true threat

exception.

B. The subjectivetest is more appropriate in light of the principles of the First Amendment

that favor narrowly tailored exceptions to the general rule that all types of speech should

be broadly protected.

There are narrowly tailored exceptions to the broad rule that speech is protectedin

addition to the non-protection of true threat. Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969) (action

that is likely to incite lawless action as unprotected speech); New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747

(1982) (child pornography is unprotected); Chaplinsky v. State of New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568

(1942) (fighting words are unprotected). These exceptions to the general rule only exist because

they are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from

them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality. R.A.V. v. City of St.

Paul, Minn., 505 U.S. 377, 382383 (1992) (quoting Chaplinsky, 315 U.S. at 572). So exceptions

to the First Amendment are very rarely allowed, and, when allowed, those exceptions are

narrowly interpreted.

1. The people have a strong vested interest in their right to free speech, and only in extreme

circumstances can this interest be circumvented.

7

It is widely accepted that above all else, the First Amendment means that government

has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, or its content. Chicago

Police Dept. v. Mosley, 408 U.S. 92, 95 (1972). This is a broad principle designed to promote

discourse between citizens, thus protectingan unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing

about of political and social changes desired by the people. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376

U.S. 254, 269 (1964) (quoting Roth v. U.S., 354 U.S. 476, 484 (1957)).

If an objective approach isapplied, the exchange of ideas would be hampered because the

standard, that any speech that a reasonable person could perceive as a threat is unprotectable,

would act as a disincentive to speakfreely and without worry that their words could be perceived

as a threat. Under this approach, a person that wants to convey an idea in a manner or method

that is questionable, as to whether areasonable person would perceive it as a threat, is more

likely to stay quiet and dissociate themselves fromthe interchange of ideas the Supreme Court

has foundso important. For example, an objective standard is likely to provide a disincentive to

citizens that wish to express their ideas, like the boisterous defendant in Watts v. U.S. did, from

participating in the debate on public issues, which the court found should be uninhibited,

robust, and wide open. 394 U.S. 705, 708 (1969).

The subjective approach should be followed because it better protects the vested interest

in a persons right to express him/herself, while following the principles that allow a true threat

exception, than the objective approach does.

2. Political hyperbole is generally given more protection than ordinary speech.

Political speech is given far more deference than other types of speech because it fits

directly into the prime directiveof the First Amendment, that of allowing an exchange of ideas.

The Supreme Court has stated that speech on public issues occupies the highest rung of the

8

hierarchy of First Amendment values, and is thus entitled special protection. Connick v. Myers,

461 U.S. 138, 145 (1983) quoting NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 913

(1982). Speech is of public concern, and thus political, if it can be fairly considered as

relating to any matter of political, social, or other concern to the community. Connick, 461 U.S.

138, 146 (1983).

A persons political speech should not be inhibited simply because the recipient may

become afraid or upset by the content of the speech. For instance, the Supreme Court decided a

case involving the Westboro Baptist Church protesting a military funeral with picket signs

containingphrases including, but not limited to, Thank God for Dead Soldiers, Fags Doom

Nations, and Priests Rape Boys. Snyder v. Phelps, 131 S. Ct. 1207, 1210 (2011). The court

found that even though the jury found the content of the signs to be outrageous, the extreme

content of the signs cannot overcome the special protection guaranteedto political speechin

Connick. Id. at 1219; Connick, 461U.S. 138, 145. To inhibit political speech by allowing

criminal action against a person simply because another person may feel upset or threatened by

the language would upset the special protections provided to political speech espousedin Snyder.

In this case, Ms. Cobbs letter to Captain Tam fits well within the definition of political

speech because the speech in her letter relates to political, social and community concerns,

therefore her letter is guaranteed, on top of the broad protections already offered to speech,

special protection. The special protection that would best implement the First Amendments

directives would be a requirement of subjective intent when determining whether a true threat

has been made.

C. Applying an objective test has the potential of creating absurd results.

9

Where possible, a court should avoid an interpretation of law that would lead to absurd

results. See U.S. v. Kirby, 74 U.S. 482 (1868). Toadopt the objective approach andinterpret that

a punishablethreat includes any statement that could be interpreted as a threat by a reasonable

person without introducing the intent of the communicating party as a factor or element would

create absurd results that turns a misstatement or misinterpretation into a federal offense

punishable by a fine or up to twenty years in prison. 18 U.S.C. 875(c) (1994). For instance, a

person not fluent in writing English couldwrite a letter, without any intent to intimidate or

threaten, that sounds threatening in Englishand be punished for the letters contents. This is

similar to the case at hand. Ms. Cobbs intended to send Captain Tams a letter of support. She

was sloppy in her delivery, as the record shows she often is, and Captain Tams perceived the

letter as a threat. Ms. Cobbs should not be subject to afine or up to atwenty year federal prison

sentence simply because Captain Tams was scared by her letter of support.

Ms. Cobbs requests that the Court reverse and remand the decision by the district court to

use an objective approach and to instead utilize the subjective approach, which is more in line

with the constitutional principles that promote the Freedom of Speech.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT MS. COBBS WAS NOT IN

CUSTODY FOR THE PURPOSES OF MIRANDA BECAUSE A REASONABLE

PERSON IN MS. COBBS POSITION WOULD NOT BELIEVE THEY WERE

FREE TO LEAVE DURING THE INTERROGATION.

[ANALYSIS OF SECOND ISSUE OMMITTED]

CONCLUSION

Ms. Cobbs respectfully requests that this court reverse the district courts decision to

admit her self-incriminating statements during trial, and to reverse the district courts decision to

apply an objective standard to the true threat exception.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- USUP strike against Davao ship owners declared illegalDocument2 pagesUSUP strike against Davao ship owners declared illegalJohn Michael VidaNo ratings yet

- DELHI STATE CANCER INSTITUTE RECRUITMENTDocument13 pagesDELHI STATE CANCER INSTITUTE RECRUITMENTKhatri SanjeevNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jose Rafael Marte, 11th Cir. (2014)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Jose Rafael Marte, 11th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Daan v. Sandiganbayan, GR Nos. 163972-77, March 28, 2008Document1 pageDaan v. Sandiganbayan, GR Nos. 163972-77, March 28, 2008Jemson Ivan WalcienNo ratings yet

- Order - Case T-515-19 - General Court of The European Union - Lego v. EUIPODocument2 pagesOrder - Case T-515-19 - General Court of The European Union - Lego v. EUIPODarius C. GambinoNo ratings yet

- Sri Lanka Procurement ManualDocument163 pagesSri Lanka Procurement ManualvihangimaduNo ratings yet

- Government of Andhra Pradesh Transport Department: WarningDocument1 pageGovernment of Andhra Pradesh Transport Department: WarningSwathi SumanNo ratings yet

- CH 2 - Doctrines in TaxationDocument29 pagesCH 2 - Doctrines in TaxationAling KinaiNo ratings yet

- Natres Full CasesDocument260 pagesNatres Full CasesN.SantosNo ratings yet

- Melbourne Storm Deloitte InvestigationDocument6 pagesMelbourne Storm Deloitte InvestigationABC News Online100% (1)

- Rodriguez Vs RavilanDocument3 pagesRodriguez Vs RavilanElerlenne LimNo ratings yet

- 2017-02-02 Calvert County TimesDocument24 pages2017-02-02 Calvert County TimesSouthern Maryland OnlineNo ratings yet

- Class Action SuitsDocument18 pagesClass Action SuitsAyush Ghiya100% (2)

- Wills and Succession CassesDocument58 pagesWills and Succession Cassesrobertoii_suarez100% (1)

- General Power of AttorneyDocument3 pagesGeneral Power of Attorneycess_rmtNo ratings yet

- Curfew Ordinance Ecq-1Document6 pagesCurfew Ordinance Ecq-1Rina TravelsNo ratings yet

- The Matrix and The ConstitutionDocument48 pagesThe Matrix and The Constitutionitaintme100% (4)

- White Gold Marine Services V Pioneer InsuranceDocument5 pagesWhite Gold Marine Services V Pioneer InsuranceKitKat ZaidNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relation Case DigestDocument106 pagesPersons and Family Relation Case DigestRod Daniel BeltranNo ratings yet

- Updated MP - Procedure To Set Up Representative Office (KPPA) in IndonesiaDocument3 pagesUpdated MP - Procedure To Set Up Representative Office (KPPA) in IndonesiaYohan AlamsyahNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - General PrinciplesDocument5 pagesLecture 1 - General PrinciplesRyan ParejaNo ratings yet

- Sullwold ComplaintSummonsDocument4 pagesSullwold ComplaintSummonsGoMNNo ratings yet

- Uzbl v. Devicewear - ComplaintDocument37 pagesUzbl v. Devicewear - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Law of ContractDocument34 pagesIntroduction To The Law of ContractCharming MakaveliNo ratings yet

- Paul Brown's Smooth Jazz HandbookDocument33 pagesPaul Brown's Smooth Jazz HandbookMeli valdes100% (1)

- D - Internet - Myiemorgmy - Intranet - Assets - Doc - Alldoc - Document - 5762 - Jurutera July 2014 PDFDocument47 pagesD - Internet - Myiemorgmy - Intranet - Assets - Doc - Alldoc - Document - 5762 - Jurutera July 2014 PDFDiana MashrosNo ratings yet

- En 13371Document11 pagesEn 13371med4jonok100% (1)

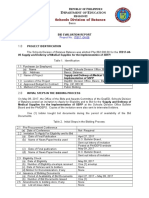

- Schools Division of Batanes: Bid Evaluation ReportDocument2 pagesSchools Division of Batanes: Bid Evaluation Reportaracelipuno100% (3)

- People Vs JanjalaniDocument3 pagesPeople Vs JanjalaniLee MatiasNo ratings yet

- Labor Standards Law 1 Semester, 2020-2021 Atty. Raidah M. Mangantulao Assignments For September 21, 2020 5:30-8:30PMDocument3 pagesLabor Standards Law 1 Semester, 2020-2021 Atty. Raidah M. Mangantulao Assignments For September 21, 2020 5:30-8:30PMEsmeralda De GuzmanNo ratings yet