Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id736207

Uploaded by

Sorana Popescu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views20 pagesSSRN-id736207

Original Title

SSRN-id736207

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSSRN-id736207

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views20 pagesSSRN Id736207

Uploaded by

Sorana PopescuSSRN-id736207

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 20

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF DIPLOMATIC

NEGOTIATION: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

FILIPE SOBRAL (fsobral@fe.uc.pt)

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT, FACULTY OF ECONOMICS

UNIVERSITY OF COIMBRA, PORTUGAL

NATLIA LEAL (nfleal@fe.uc.pt)

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS DEPARTMENT, FACULTY OF ECONOMICS

UNIVERSITY OF COIMBRA, PORTUGAL

2

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF DIPLOMATIC NEGOTIATION:

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

ABSTRACT

This paper sought to examine the ethicality of negotiation behaviors in the context of

diplomatic negotiations. Mismatched ethical expectations are one of the biggest barriers to

effective conflict resolution. Using inappropriate tactics can hinder the negotiation process

and cause the breakdown. Despite this, there is scant understanding of how diplomats and

political scientists view the ethics and morals underlying the negotiation process. Twenty

senior diplomats from Portugal rated their perceptions of the appropriateness and perceived

efficacy of forty five ethically ambiguous negotiation tactics (EATN). Results showed that

respondents judged the ethical appropriateness of tactics of emotional deception more

favorably than tactics of cognitive deception. Results also indicated significant differences in

the perceptions of the appropriateness of most tactics and their efficacy in the international

arena. Implications for the role of ethics in diplomatic negotiation are discussed.

KEYWORDS: Negotiation; Ethical Decision-Making; Diplomacy

TYPE OF PAPER: Empirical

3

INTRODUCTION

The international negotiation arena is populated by several types of actors from

international organizations, to multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations,

groups of people, and individuals. Still, the nation-state remains the most relevant actor

(Rasmussen, 1997). International negotiations are characterized by inter-state relations, and

are the process of reaching agreements such as official and unofficial diplomatic

communications, ministerial meetings, meetings in international organizations, and

summitry (Druckman, 1997: 90).

However, even if technically the actors in a negotiation are states or governments,

ultimately, they will have to be represented by individuals. Different individuals have

different perceptions about the decision-making process. This is why many international

negotiations often fail (Gulbro & Herbig, 1996). One particular area that can cause the

impasse or even the breakdown of a negotiation is mismatched expectations about what

constitutes appropriate negotiating behavior. Tactics involving deception or any other variant

of untruthfulness are commonly available to negotiators and are perceived as more or less

acceptable depending on who is asked (Anton, 1990). Some researchers point to the

expectation of deception as a commonplace of bargaining (Carson, 1993; Friedman &

Shapiro, 1995; Strudler, 1995), while others reject the use of any form of dishonesty in

negotiation (Provis, 2000; Reitz et al., 1998). Thus, it is important that international

negotiators understand what constitutes an acceptable or unacceptable tactic. Knowing what

is considered as an ethical or unethical behavior will help negotiators better understand the

other party and to manage their emotional responses during the decision-making process.

This paper explores how diplomats view the ethicality of several negotiation gambits

that can be regarded as deceptive in the context of international negotiation. This study adds

to the understanding of ethical decision-making in negotiation by focusing on the perspective

4

of political scientists and diplomats. The objectives proposed in this paper are: (1) identify

the tactics and behaviors as ethically acceptable or unacceptable in the context of diplomatic

negotiations; (2) examine the extent to which diplomats distinguish between cognitive tactics

of deception versus emotional tactics of deception; (3) assess the relationship between the

their perceptions about the appropriateness and efficacy of ethically ambiguous negotiation

tactics (EANT).

ETHICS IN DIPLOMATIC NEGOTIATION

Diplomacy is one of the peaceful instruments used by states to implement their

foreign policies and uphold their national interests at the international level (Ballesteros,

1995). It includes a wide range of activities among which is negotiation, for some, the most

important part of the diplomatic activity (Magalhes, 1996: 81). According to Holsti (1995:

140), diplomacy is used primarily to reach agreements, compromises, and settlements where

government objectives conflict. This definition is very similar to how negotiation is defined

a process of potentially opportunistic interaction by which two or more parties, with some

apparent conflict, seek to do better through jointly decided action than they could otherwise

(Lax & Sebenius, 1986: 11) , in the sense they both focus on the need to reconcile divergent

interests. In fact, for Schelling (1980: 168), diplomacy is bargaining. Therefore, while

diplomats, through negotiation, strive to achieve the goals defined by their home government,

they may stumble upon some ethical dilemmas. As with any other people involved in a

negotiation, ethical issues are always present (Raiffa, 1982), and may affect the way they

behave and react in a negotiation.

The issue of ethics in international relations, namely the relation of ethics and moral

elements with foreign policy and the national interest, has often been the center of

5

discussions among academics and practitioners (Rosenthal, 1999; Valls, 2000). Debates on

human rights, global justice, just war theory, sovereignty or non-interference, all carry ethical

concerns (Hoffmann, 1999). But specific research on ethics in diplomatic negotiations is very

recent and scant.

In a broad sense, ethics is related with the compliance with a certain number of rules

and principles that define the adequate and admissible way to conduct. In the international

arena, ethics relates to the behavior of states, and ethical standards derive from several

features, such as international norms and standards, or socio-cultural, political, religious, and

historical norms within the state, as well as from individual conscience (Holsti, 1995). Since

states are often represented by their diplomats, their behavior is a crucial element of

international ethics. Even though some argue that it is not possible or even desirable to search

for the application of ethics in the international affairs (Welch, 2000; Cf. also Vall, 2000;

Donohue & Hoobler, 2002), policy-makers and policy-implementers, as diplomats, are role

players and are often, implicitly or explicitly, faced with the need to choose between their

conscience and the realization of their established goals and the alleged national interests

these goals incorporate. As Rosenthal (1999: 2-3) says policy decisions can be firmly rooted

in ethics while avoiding the perils of moralism and absolutism on the one hand and empty

relativism on the other. An example of how the behavior of diplomatic agents may affect our

daily lives is the impact of negotiations developed within the European Union, which are

generally conducted within the Permanent Representatives Council (the COREPER) by the

ambassadors and diplomatic staff of each member state.

Different actors in a negotiation tend to define ethics in different ways. Welber (n/d:

28-29), for instance, suggests that there are two main approaches to ethics one that views

negotiation much like a competitive sport or game [], accompanied by norms of behavior

separate from the norms of everyday human interaction, and another, more idealistic, under

6

which one should maintain the same principles of honesty in negotiation that one would

apply in other interpersonal relations , plus a third pragmatic and mixed approach that

recognizes that deception is an inherent part of the negotiation process but that it should be

used sparingly, on a case by case basis. Lewicky et al. (2003: 273-245), on the other hand,

propose four approaches to what may or not constitute an ethical behavior. Ethical reasoning

may result from considerations about end-result ethics (principles of utilitarianism), rule

ethics (principles of rule utilitarianism), social contract ethics (principles of community-based

socially acceptable behavior) or personalistic ethics (determining what is right by turning to

ones conscience). In a negotiation encounter, the incentives to cross the line into the territory

of ethically ambiguous behavior are a function of the characteristics of the negotiation

situation and the differences in the motivation of the parties (OConnor & Carnevale, 1997).

Nevertheless, it is important to notice that some form of deception is frequent and inherent to

the negotiation process. In a study with experienced negotiators, more than one-third engaged

in both active and passive misrepresentation within one single encounter (Murnighan et al.,

1999).

CLASSIFYING AND MEASURING THE APPROPRIATENESS OF EANTs

The main objective of this paper is to understand how diplomats evaluate ethically

ambiguous negotiation tactics regarding their acceptability and perceived efficacy. Measuring

the individual attitudes toward EANTs is potentially useful to identify intergroup differences

in order to predict the likelihood that they will use such tactics in a negotiation situation.

Lewicki and Robinson (1998) and Robinson et al. (2000) developed a measure of

attitudes toward such tactics the Self-Reported Inappropriate Strategies scale (SINS scale).

The SINS scale reports judgments of appropriateness of five categories of tactics: (1)

7

bluffing, (2) inappropriate information gathering, (3) attacking opponents network, (4)

misrepresentation, (5) traditional competitive bargaining. Using the SINS scale several

studies have been conducted to understand which factors may shape a negotiators

predisposition to use unethical tactics. Findings suggest that demographic and personality

characteristics of the respondents affected the way they perceive the acceptability of such

tactics (Lewicki et al., 2003). Other studies have also found that ratings of acceptability of

EANTs vary across occupation groups (Anton, 1990), across cultures (Volkema, 1997, 1998,

1999) and across situations (Garcia et al., 2001; Volkema & Fleury, 2002).

Recently, Barry (1999) and Barry et al. (2003) proposed one more category to the

SINS scale emotional manipulation. In fact, its not only the manipulation of information in

a negotiation encounter that may involve deception. The manipulation of the emotional state

may also entail some degree of dishonesty. There is empirical evidence that emotional

deception is harder to detect than factual deception (Hocking et al., 1979), increasing the

temptation to effectively deploy such tactics. Moreover, some authors point that emotion

management is a more intrinsic and normative behavior in interpersonal relations than any

other form of deception (Barry et al. 2003; Burleson & Planalp, 2000). Results from Barrys

work suggest that tactics of emotional manipulation are more ethically appropriate than

tactics of cognitive manipulation of information (Barry, 1999; Barry et al., 2003).

Despite several studies conducted using the SINS scale, some authors raised some

concerns about the appropriateness of the SINS scale for identifying a typology of EANTs

(Rivers, 2004; Reitz et al., 1998). They argued that the categories are not conceptually

distinct and that the SINS scale does not offer content adequacy of the field of EANTs. For

example the SINS scale does not include tactics like omission or distraction, behaviors that

can be considered deceptive in a negotiation situation.

8

These concerns led to the development of an alternative inventory of EANTs that

included types of tactics absent in the SINS scale. This new inventory consists of 45 items

that are being tested and validated and represents the initial step in the development of an

alternative scale for measuring ethically ambiguous tactics.

METHOD

The research subjects were ambassadors and senior staff of the Portuguese diplomatic

body. Twenty participants completed the questionnaire containing the proposed measures,

which were mailed through the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Although the number

of responses does not allow to make statistical generalizations it was important to receive

opinions from qualified and experienced negotiators. One of the main critiques that has been

pointed to ethics research in negotiation is that it normally uses MBA students as subjects,

samples that are too homogeneous and with a limited negotiation experience.

To evaluate the perceptions of Portuguese diplomats, a three-section questionnaire

was designed. In the first part participants completed the appropriateness ratings of 45

ethically ambiguous negotiation tactics. Instead of considering any specific definition for

what ethics is or should be, instructions directed participants to consider each tactic in the

context of the negotiations that usually take place in scope of the diplomatic activity.

Participants were then asked to indicate how ethically appropriate they would think that each

tactic was in that context, using a 7-point scale (1-completely unacceptable to 7-completely

acceptable).

In the second section, participants provided a second rating for each of the same 45

tactics, but this time judging the perceived efficacy of such tactic in the context of diplomatic

activity. The ratings of efficacy were also measured on a 7-point scale (1-not at all effective

9

to 7-very effective). Finally, in the last section the participants provided some demographic

and professional data.

RESULTS

Due to the reduced number of responses, a factor analysis is not a valid option to treat

the responses; therefore the analysis will focus on a more exploratory level, with emphasis on

descriptive analysis and in series of bivariate comparisons. For analysis purposes mean

ratings of each group of EANT will be used (varying from 1 to 7 and with 4 representing the

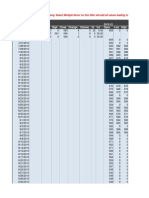

neutral value). Table I summarizes the results for each group of tactics for both

appropriateness and perceived efficacy ratings.

TABLE I APPROPRIATENESS AND EFFICACY OF EANTS

Category Appropriateness Efficacy

1. Traditional Competitive Tactics 5,25 5,13

2. Misrepresentation/Lying 2,87 3,55

3. Attacking Opponents Network 2,62 3,13

4. Bluffing (false promises and threats) 2,65 3,73

5. Inappropriate Information Gathering 3,71 4,71

6. Manipulation of Positive Emotions 5,39 5,46

7. Manipulation of Negative Emotions 4,36 4,83

8. Complete Repression of Emotions 6,18 6,05

9. Omission or Partial Disclosure 4,60 4,98

10. Distraction 4,70 4,65

10

The results show that some forms of untruth are considered ethically appropriate

among diplomats. Tactics that conceal what is going on in the mind of the negotiator (e.g.

exaggeration or hiding the value of something) are considered acceptable and within the rules

of negotiation. Tactics that repress emotions, keeping a poker face, even if the negotiator is

stressed or annoyed, are also regarded as completely acceptable. The manipulation of positive

emotions is the other group of tactics that diplomats consider ethically appropriate.

On the other hand, while some tactics are completely rejected, like misrepresentation,

bluffing and attacking the opponents network, others are accepted by some and rejected by

others. Among these are tactics of omission (hidden facts or partial disclosure), distraction

(avoiding questions or direct the attention of the opponent to minor aspects) and manipulation

of negative emotions.

In terms of perceived efficacy, the most effective EANT is the complete repression of

emotions, and the least effective ones are attacking the opponents network,

misrepresentation and bluffing. Traditional competitive tactics, as emotional manipulation

tactics, seem to be reasonably effective among diplomats. Tactics that are related to the

collection, communication and sharing of information (5, 9 & 10) divide the opinions of the

diplomats, being considered by some as moderately effective and by others as moderately

ineffective.

To examine if there are differences in the way diplomats perceive cognitive and

emotional forms of deception, series of bivariate comparisons were conducted. The means

and comparisons tests between the manipulation of positive emotions (e.g. sympathy or

enthusiasm) and tactics of cognitive manipulation show that diplomats regard the strategic

expression of positive feelings as a more acceptable behavior than other forms of deception.

The exception are tactics of competitive bargaining (sig. 0,566).

11

Different results were obtained for the comparison between tactics of negative

manipulation and tactics of cognitive manipulation. Diplomats show more positive attitudes

towards some tactics of cognitive deception (traditional competitive tactics, omission and

distraction) than to negative manipulation of emotion. However, statistically significant

differences were found between negative expression of feelings and some tactics of

manipulation of information (namely, misrepresentation, bluffing and attacking the

opponents network all sig. < 0.001).

As for the comparisons of the efficacy between such tactics in the context of

diplomatic negotiation, the results are very similar to those obtained in the appropriateness

ratings. Tactics of manipulation of positive feelings are considered a more effective attitude

than cognitive deception. However, traditional competitive tactics (sig. 0,213) and omission

(sig. 0,198) are rated by the respondents as being as much effective as manipulation of

positive emotions. Tactics of negative expression of emotions are regarded as more effective

than some tactics of information manipulation (misrepresentation, bluffing and attacking

opponents network all sig. <0,001) but no differences were found in comparison to tactics

such as traditional competitive bargaining (sig. 0,105), inappropriate information gathering

(sig. 0,691), omission (sig. 0,613) or distraction (sig. 0,523).

The third objective was to examine the relationship between the perceptions of

appropriateness and efficacy of such tactics in the context of diplomatic activity. To test these

relationships paired comparisons were conducted between the means of appropriateness and

efficacy ratings. Significant differences were only found in misrepresentation (sig. 0,008),

attacking the opponents network (sig. 0,035), bluffing (sig. 0,005), and inappropriate

information gathering (sig. 0,001). All these tactics were considered ethically unacceptable;

however diplomats recognize that these tactics can be more effective than they are

appropriate in diplomatic negotiations.

12

DISCUSSION

The findings reported in this study contribute to research on negotiation ethics in four

major ways. Most importantly, this is among the first studies to measure the attitudes of

diplomats toward ethically ambiguous negotiation tactics. Second, the results show

differences in how these individuals assess the acceptability and efficacy of cognitive and

emotional manipulation tactics. Third, the findings suggest that there are differences in terms

of perceived efficacy and appropriateness of several EANTs. Finally, this study is the first

step to develop alternative measures of ethically ambiguous negotiation tactics, including

tactics of emotional deception and other forms of cognitive deception like omission or partial

disclosure and distraction.

In an era of globalization, where impersonality often seems to be one of its main

effects, it is important to remember that foreign policies and diplomacy are a result of

individuals behavior. As Ballestero (1995) underlines, the human factor is crucial in the

diplomatic activity, and as Zartman (1999) would add, negotiation is a vital process to assure

the settlement of conflicts that often arise between states and between their representatives.

Since these international disputes often appear due to different interpretation of what should

be done, the compliance with a certain number of norms and procedures should also be on the

mind of those who sometimes lead these negotiation processes. As this study has shown,

diplomats are sensible to ethical issues, but not always in the same manner. The rules of the

game seem to accept some passive forms of dishonesty (lies of omission) but do not

welcome some more factual manipulations, namely more active tactics such as

misrepresentation, false promises or threats (OConnor & Carnevale, 1997; Schweitzer &

Croson, 1999).

Regarding the comparison between cognitive and emotional forms of deception, the

present study suggests some mixed opinions. The role of emotion in negotiation has been

13

either ignored or treated as a uniquely destructive force that disrupts a rational process

(Putnam, 1994) and there was very little research that investigated affective processes in

negotiation (Barry & Oliver, 1996; Thompson et al., 1999). However, negotiation typically

occurs when there is conflict and conflict cannot be free of emotion and anxiety (Greenhalgh,

2002). Lately, research in this area has greatly expanded and moved beyond early cognition-

focused approaches (Barry et al., 2004; Bodtker & Jameson, 2001; Fulmer & Barry, in press;

Ogilvie & Carsky, 2002). Scholars have given more explicit attention to the emotional

components, recognizing it as a complementary element of cognition in the negotiation

process. However, the present study does not corroborate the results of previous studies.

Barry (1999) and Barry et al. (2003) found evidences that participants held more favorable

attitudes toward the use of emotional management tactics when compared to cognitive forms

of deception, and reported higher levels of self-efficacy for emotion management tactics.

Diplomats consider that the control of emotion and the expression of positive feelings are

acceptable and effective; however they do not share the same opinion in regard to the

expression of negative emotions. These are considered less acceptable and less effective than

some tactics of cognitive manipulation of information.

With respect to comparison between appropriateness and efficacy of EANTs the

results indicate that some tactics are regarded as more effective than they are ethically

appropriate. Maybe because some of these tactics may eventually be considered as a form of

propaganda deliberate attempts by governments, through their diplomats and

propagandists, to influence the attitudes and behavior of foreign populations (Holsti, 1995:

152). and their governments , especially behaviors like the manipulation and gathering of

information, misrepresentation/lying and false promises and threats. The activity of

propaganda is one that is more concerned with the effectiveness of its results, than with the

search for a certain truth or compliance with any specific standards. Perhaps this is why

14

diplomats recognize some tactics as ethically unacceptable but somewhat effective in the

diplomatic context.

Finally, this study also intended to develop a new measuring instrument of ethically

ambiguous negotiation tactics. Despite de wide acceptance and validation of the SINS scale

(Lewicki & Robinson, 1998; Robinson, Lewicki & Donohue, 2000) there is room to include

other forms of deception. Some attempts have been made to propose new categories of

EANTs (Rivers, 2004; Reitz et al., 1998) but none, yet, has been completely validated as the

SINS scale. The present study represents the first step to an alternative scale to classify and

measure EANTs.

Some limitations in this research should be mentioned. First, the reduced number of

responses does not allow to conduct a more validated analysis and to generalize the findings.

However, targeting a sample of experienced and professional negotiators, among which were

several ambassadors, was preferred to using graduate students with limited negotiation

experience. Second, the measuring instrument is not yet validated, although other researches

have been conducted using other professional groups and countries.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study reveal the perceptions of diplomats

about the behaviors that are acceptable and effective in the international negotiation arena.

Results show that in the opinion of Portuguese diplomats some forms of deception are

regarded as honest and ethically acceptable, while others are completely rejected and

disapproved in diplomatic negotiations. Since greater honesty in diplomacy seems to be

considered a sign of the maturing of the diplomatic system (Berridge, 1995), it is expected

that this study represents a contribution to the positive evolution of man and its forms of

organization and governance.

15

REFERENCES

ANTON, R., Drawing the line: An exploratory test of ethical behavior in negotiations. The

International Journal of Conflict Management, 1, 1990, pp. 265-280.

BALLESTEROS, Angel, Diplomacia y relaciones internacionales. Madrid: Ministerio de

Asuntos Exteriores. 1995, 3rd ed.

BARRY, B., & OLIVER, R., Affect in dyadic interaction. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 67, 1996, pp. 127-143.

BARRY, B., The tactical use of emotion in negotiation. In R. J. Bies, R. J. Lewicki, & B. H.

Sheppard (Eds.), Research on Negotiation in Organizations, (volume 7, pp. 93-121).

Stamford, CT: JAI Press, 1999.

BARRY, B., FULMER, I., & LONG, A., Attitudes regarding the ethics of negotiation tactics:

Their influence on bargaining outcomes and negotiator reputation (Draft manuscript),

Nashville, Tennessee: Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University,

2003.

BARRY, B., FULMER, I., & VAN KLEEF, G., I laughed, I cried, I settled: The role of

emotion in negotiation. In M. Gelfand and J. Brett (Eds.), The Handbook of Negotiation

and Culture (pp. 71-94). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

BERRIDGE, G. R., Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice

Hall/Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1995.

BODTKER, A., & JAMESON, J., Emotion in conflict formation and its transformation:

Application to organizational conflict management. International Journal of Conflict

Management, 12, 2001, pp. 259-275.

BURLESON, B., & PLANALP, S., Producing emotion(al) messages. Communication

Theory, 10, 2000, pp. 221-250.

16

CARSON, T., Second thoughts about bluffing? Business Ethics Quarterly, 3 (4), 1993, pp.

317-341.

DONAHUE, William A. & HOOBLER, Gregory D. Relational Frames and Their Ethical

Implications in International Negotiations: An analysis Based on the Oslo II

Negotiations, International Negotiations, 7, 2002, 143-167.

DRUCKMAN, Daniel, International Negotiation. In ZARTMAN, I. William,

RASMUSSEN, J. Lewis (eds.), Peacemaking in International Conflict: methods and

Techniques, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997, pp. 81-123.

FRIEDMAN, R., & SHAPIRO, D., Deception and mutual gains bargaining: Are they

mutually exclusive? Negotiation Journal, 11, 1995, pp. 243-253.

FULMER, I., & BARRY; B., The smart negotiator: Cognitive ability and emotional

intelligence in negotiation. International Journal of Conflict Management, (in press).

GARCIA, S., DARLEY, J., & Robinson, R., Morally questionable tactics: Negotiations

between district attorneys and public defenders. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 27, 2001, pp. 731-743.

GREENHALGH, L., Managing anxiety in negotiated decision-making. Working paper no.

02-05. Darmouth, NH: Tuck School of Business, 2002.

GULBRO, R., & HERBIG, P., Cross-cultural negotiation processes. Industrial Management

& Data Systems, 96 (3), 1996, pp. 17-23.

HOCKING, J., BAUCHNER, J., KAMINSKI, E., & MILLER, G., Detecting deceptive

communication from verbal, visual, and paralinguistic cues. Human Communication

Research, 6, 1979, pp. 33-46.

HOFFMANN, Stanley, The Political Ethics in International Relations. In Ethics &

International Affairs: a Reader, ROSENTHAL, Joel H. (ed.), Washington DC:

17

Georgetown University Press, Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs,

1999, 2

nd

ed., pp. 28-49.

HOLSTI, K. J., International Politics: a Framework for Analysis, Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall, 7th ed., 1995.

LAX, D., & SEBENIUS, J., The manager as negotiator: Bargaining for cooperation and

competitive gain. New York: Free Press, 1986.

LEWICKI, R., & ROBINSON, R., Ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: An empirical

study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1998, pp. 665-682.

LEWICKI, Roy J., BARRY, Bruce, SAUNDERS, David M., MINTON, John W.,

Negotiation, Boston: MacGraw Hill/Irwin, 4

th

ed. (MacGraw-Hill International Editions),

2003.

MAGALHES, Jos Calvet de, Diplomacia Pura, Venda Nova: Bertrand Editora, 2

nd

ed.,

1996.

MURNIGHAN, K., BABCOCK, L., THOMPSON, L., & PITTUTLA, M., The information

dilemma in negotiations: Effects of experience, incentives, and integrative potential.

International Journal of Conflict Management, 10 (4), 1999, pp. 313-339.

OCONNOR, K., & CARNEVALE, P., A nasty but effective negotiation strategy:

Misrepresentation of common-value issue. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

23, 1997, pp. 504-515.

OGILVIE, J., & CARSKY, M., Building emotional intelligence in negotiations. International

Journal of Conflict Management, 13 (4), 2002, pp. 315-430.

PROVIS, C., Ethics, deception, and labor negotiation. Journal of Business Ethics, 28, 2000,

pp. 145-158.

PUTNAM, L., Challenging the assumptions of traditional approaches to negotiation.

Negotiation Journal, 10, 1994, pp. 337-346.

18

RAIFFA, Howard, The art and science of negotiation: how to resolve conflicts and get the

best out of bargaining. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,

1996, 13

th

printing (1

st

edition from 1982).

RASMUSSEN, J. Lewis, Peacemaking in the Twenty-First Century: New Rules, New

Roles, New Actors. In ZARTMAN, I. William, RASMUSSEN, J. Lewis (eds.),

Peacemaking in International Conflict: methods and Techniques, Washington, DC:

United States Institute of Peace Press, 1997, pp. 23-50.

REITZ, H., WALL, J., & LOVE, M., Ethics in negotiation: Oil and water or good

lubrication? Business Horizons, May-June, 1998, pp. 5-14.

RIVERS, C., What are they thinking? Considerations underlying negotiators ethical

decisions. 2004 Annual Meeting, Academy of International Business Conference,

Stockholm, Sweden, 2004.

ROBINSON, R., LEWICKI, R., & DONAHUE, E., Extending and testing a five factor model

of ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: Introducing the SINS scale. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 21, 2000, pp. 649-664.

ROSENTHAL, Joel H., Introduction: Ethics through the Cold War and After. In Ethics &

International Affairs: a Reader, ROSENTHAL, Joel H. (ed.), Washington DC:

Georgetown University Press, Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs,

1999, 2

nd

ed., pp. 1-7.

SCHELLING, T, The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

1980.

SCHWEITZER, M., & CROSON, R., Curtailing deception: The impact of direct questions on

lies and omissions. International Journal of Conflict Management, 10, 1999, pp. 225-248.

STRUDLER, A., On the ethics of deception in negotiation. Business Ethics Quarterly, 5,

1995, pp. 805-822.

19

THOMPSON, L., NADLER, J., & KIM, P., Some like it hot: The case for emotional

negotiator. In L. Thompson, J. Levine, & D. Messick (Eds.) Shared Cognition in

Organizations: The Management of Knowledge (p. 139-161). Mahwah: Erlbaum, 1999.

VALLS, Andrew (ed.), Ethics in International Affairs: Theories and Cases. Lanham,

Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

VOLKEMA, R., Perceptual differences in appropriateness and likelihood of use of

negotiation behaviors: A cross-cultural analysis. The International Executive, 39, 1997,

pp. 335-350.

VOLKEMA, R., A comparison of perceptions of ethical negotiation behavior in Mexico and

the United States. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 9, 1998, pp. 218-

233.

VOLKEMA, R., Ethicality in negotiations: An analysis of perceptual similarities and

differences between Brazil and the United States. Journal of Business Research, 45, 1999,

pp. 59-67.

VOLKEMA, R., & FLEURY, M., Alternative negotiation conditions and the choice of

negotiation tactics: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 36, 2002, pp.

381-398.

WELBER, Kevin, Tool Kit for Negotiation and Mediation, The Institute for International

Mediation and Conflict Resolution (IIMCR), n/d [Available online for alumni students at

www. iimcr.org]

WELCH, David A., Morality and the National Interest. In VALLS, Andrew (ed.), Ethics

in International Affairs: Theories and Cases, Lanham (Maryland): Rowman & Littlefield,

2000, Ch. 1, pp. 3-12.

ZARTMAN, I. William, Introduction: Toward the Resolution of International Conflicts. In

ZARTMAN, I. William, RASMUSSEN, J. Lewis (eds.), Peacemaking in International

20

Conflict: methods and Techniques, Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace

Press, 1997, pp. 3-19

You might also like

- International Studies Millennium - Journal ofDocument31 pagesInternational Studies Millennium - Journal ofdinpucioasaNo ratings yet

- Trade Relation (Spring 2009) .Ferris, Garabelli (China IPR)Document22 pagesTrade Relation (Spring 2009) .Ferris, Garabelli (China IPR)Sorana PopescuNo ratings yet

- The Protection and Enforcement of Intellectual Property in China Since Accession To The WTO: Progress and RetreatDocument6 pagesThe Protection and Enforcement of Intellectual Property in China Since Accession To The WTO: Progress and RetreatApollonia TreNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Negotiations in Resolving International DisputesDocument14 pagesThe Prevalence of Negotiations in Resolving International DisputesSorana PopescuNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Negotiations in Resolving International DisputesDocument14 pagesThe Prevalence of Negotiations in Resolving International DisputesSorana PopescuNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in US Trade NegotiationDocument391 pagesCase Studies in US Trade NegotiationzuppadipomodoroNo ratings yet

- Us ChinaDocument6 pagesUs ChinaSorana PopescuNo ratings yet

- WTIO historical daily data 2010-12Document52 pagesWTIO historical daily data 2010-12Sorana PopescuNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Importance of ethics - whose perspectivesDocument26 pagesImportance of ethics - whose perspectivesMichael MatshonaNo ratings yet

- 1993 Bar Questions Labor StandardsDocument8 pages1993 Bar Questions Labor StandardsJamie Dilidili-TabiraraNo ratings yet

- I. T SLP .: HAT Is Maintainable in The Present CaseDocument2 pagesI. T SLP .: HAT Is Maintainable in The Present CaseyashNo ratings yet

- Yossi Moff - Unit 1 Lesson 4 - 8th Grade - Reflection Loyalists Vs PatriotsDocument2 pagesYossi Moff - Unit 1 Lesson 4 - 8th Grade - Reflection Loyalists Vs Patriotsapi-398225898No ratings yet

- Legal Literacy Project: Amity Law School, NoidaDocument14 pagesLegal Literacy Project: Amity Law School, Noidaprithvi yadav100% (2)

- Useful Phrases For Writing EssaysDocument4 pagesUseful Phrases For Writing EssaysAlexander Zeus100% (3)

- 2017 11 19 - CE483 CE583 Con Cost Estimating Syllabus - v2 - 0Document6 pages2017 11 19 - CE483 CE583 Con Cost Estimating Syllabus - v2 - 0azamgabirNo ratings yet

- Crowley - Liber Tzaddi Vel Hamus Hermeticus Sub Figurâ XCDocument6 pagesCrowley - Liber Tzaddi Vel Hamus Hermeticus Sub Figurâ XCCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (2)

- The Emotional Intelligence-Sales Performance Relationship PDFDocument94 pagesThe Emotional Intelligence-Sales Performance Relationship PDFelisaNo ratings yet

- HUMAN RIGHTS LAW CHAPTERSDocument5 pagesHUMAN RIGHTS LAW CHAPTERSMegan Mateo80% (10)

- Assignment TpaDocument8 pagesAssignment TpaatulNo ratings yet

- RODIL Enterprises vs. Court of Appeals case on ownership rightsDocument2 pagesRODIL Enterprises vs. Court of Appeals case on ownership rightsVox Populi100% (2)

- University of Buea - CameroonDocument17 pagesUniversity of Buea - CameroonL'ange EtrangeNo ratings yet

- Priroda Uzvraca Udarac - Razmisljanje Na TemuDocument5 pagesPriroda Uzvraca Udarac - Razmisljanje Na TemuDoReMiNo ratings yet

- Tugas Pra Uts Resensi Jurnal Ilmu FilsafatDocument23 pagesTugas Pra Uts Resensi Jurnal Ilmu FilsafatPricella MutiariNo ratings yet

- Certificate-Of-Good-Moral-Character-Autosaved (AutoRecovered)Document7 pagesCertificate-Of-Good-Moral-Character-Autosaved (AutoRecovered)Winie MireraNo ratings yet

- Philo Module 3Document4 pagesPhilo Module 3Edmon AguilarNo ratings yet

- Chapter-2 Review of Literature: Naipunnya Institute of Management and Information Technology, PongamDocument7 pagesChapter-2 Review of Literature: Naipunnya Institute of Management and Information Technology, PongamAmal Jose MambillyNo ratings yet

- Mutual Non Disclosure AgreementDocument3 pagesMutual Non Disclosure AgreementRocketLawyer78% (9)

- Sentiment Moral Decision MakingDocument22 pagesSentiment Moral Decision MakingMay Rose Domingo100% (1)

- Aca Code of EthicsDocument24 pagesAca Code of EthicsAvhegail Pangan100% (2)

- Suzara Vs BenipayoDocument1 pageSuzara Vs BenipayoGui EshNo ratings yet

- Ethics Midterm ExaminationDocument10 pagesEthics Midterm ExaminationLyka Jane BucoNo ratings yet

- Colregs Part F New RulesDocument3 pagesColregs Part F New RulesRakesh Pandey100% (1)

- Moral Dilemmas Ethics PDFDocument24 pagesMoral Dilemmas Ethics PDFRyle Ybanez TimogNo ratings yet

- Internet CensorshipDocument7 pagesInternet Censorshipapi-283800947No ratings yet

- 1sebastian Vs CalisDocument6 pages1sebastian Vs CalisRai-chan Junior ÜNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography - Joel Kim 1Document5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography - Joel Kim 1api-316739257No ratings yet

- Lic Golden Jubilee FoundationDocument4 pagesLic Golden Jubilee Foundationrupeshmore145No ratings yet

- (변형기출) 올림포스 (2) 1 - 18강 (949문항) - 복사본Document268 pages(변형기출) 올림포스 (2) 1 - 18강 (949문항) - 복사본sdawNo ratings yet