Professional Documents

Culture Documents

19 2 4

Uploaded by

Ashley Sanchez0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views8 pagesTwo widely-used contemporary violin teaching methods, by Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) and Paul Rolland (1911-1978), were examined and compared. In this article the similarities and differences between them were compared, and advantages of using both violin methods were discussed.

Original Description:

Original Title

19_2_4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTwo widely-used contemporary violin teaching methods, by Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) and Paul Rolland (1911-1978), were examined and compared. In this article the similarities and differences between them were compared, and advantages of using both violin methods were discussed.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views8 pages19 2 4

Uploaded by

Ashley SanchezTwo widely-used contemporary violin teaching methods, by Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) and Paul Rolland (1911-1978), were examined and compared. In this article the similarities and differences between them were compared, and advantages of using both violin methods were discussed.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Mays 2011 Cilt:19 No:2 Kastamonu Eitim Dergisi 401-408

May 2011 Vol:19 No:2 Kastamonu Education Journal

COMPARING TWO CONTEMPORARY VIOLIN TEACHING

METHODS: SUZUKI AND ROLLAND

Dilek GKTRK CARY

Karabk niversitesi, Safranbolu Fethi Toker Gzel Sanatlar ve Tasarm Fakltesi,

Mzik Blm, Safranbolu-Karabk, Trkiye

Abstract

In the present study, two widely-used contemporary violin teaching methods, by Shinichi

Suzuki (1898-1998) and Paul Rolland (1911-1978), were examined and compared. These

two approaches have been widely used at American schools since 1960s. In this article the

similarities and differences between them were compared, and advantages of using both violin

methods were discussed.

Key Words: violin teaching in the United States; Shinichi Suzuki; Mother Tongue Method;

Talent Education; Paul Rolland

K ADA KEMAN METODUNUN KARILATIRILMASI:

SUZUKI VE ROLLAND

zet

Bu almada Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) ve Paul Rolland (1911-1978) tarafndan ortaya

karlm ok kullanlan 2 keman retim metodu incelenmi ve karlatrlmtr. Bu 2 retim

yaklam Amerikan okullarnda 1960lardan itibaren geni bir alanda kullanlmaktadr. Bu

makalede bu metodlarn benzerlikleri ve farkllklar karlatrlm ve her ikisinin de keman

retimindeki faydalar tartlmtr.

Anahtar Szckler: Amerika Birleik Devletlerinde keman retimi; Shinichi Suzuki;

Ana Dil Metodu; Yetenek Eitimi; Paul Rolland

1. Introduction

Between 1950 and 1960 a rapid progress was done in string programs in American

public schools. That time can be named as Renaissance in American string educati-

on. This growth was largely due to the efforts of the MENC String Instruction Com-

mittee and the ASTA [American String Teachers Association] National String Plan-

ning Committee as follows:

In 1951, the frst issue of the American String Teacher was published. This

journal provided string-teaching articles for both private and public school

Dilek GKTRK CARY... 402

Mays 2011 Cilt:19 No:2 Kastamonu Eitim Dergisi

string teachers.

The MENC [Music Educators National Conference] String Instruction Com-

mittee also published a series of reports that dealt with various aspects of pub-

lic schools string teaching.

ASTA sponsored yearly summer workshops and clinics for public school

string teachers. (1).

Another important development in string education in 1950s was the foundation

of the National School Orchestra Association (NSOA). NSOA was instituted in 1958.

NSOAs mission was into further the developments of school orchestras in the Uni-

ted States by increasing the status and quality of school orchestra instruction to that of

school boards (2). NSOA and ASTA engaged in 1998 and their name has been anno-

unced as ASTA with NSOA since this date.

The 1960s witnessed major social changes in the United States. As the midd-

le class continued to move to the suburbs, a growing economic disparity developed

between the socioeconomic classes and funding for urban schools declined dramati-

cally. (3). To make education more accessible for particularly culturally disadvan-

taged children, Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was completed in

1965. Title IV of this act was related to fund music research projects all over the

United States. Paul Rollands String Research Project at the University of Illinois in

Urbana-Champaign, Illinois was one of those 48 projects. In his project Rolland came

the awareness that violin playing must incorporate the most natural physical motions

allowing all string players to play with ease and beauty of tone. By applying balanced

body positions to violin playing, physical tension is reduced. (4). He also made a se-

ries of fourteen flms called The Teaching of Action in String Playing in which how to

achieve this freedom was demonstrated. Each flm has actions, such as Left Hand Po-

sition, Bow Strokes, Vibrato, and the procedure in string playing is established syste-

matically. His basic principal was as follows: Good rhythm concepts are the basis of

all well controlled movements, otherwise our playing becomes disorganized and con-

fused. (5)

2. Shinichi Suzuki (1898-1998) and His Mother Tongue Met-

hod1

The most infuential fgure in string education in the United States was Shinichi

Suzuki (1898-1998). Originally from Japan and studied violin in Germany for six ye-

ars, Suzuki developed the Talent Education or the Mother Tongue method in Japan af-

1. For more information about Shinichi Suzuki, his string teaching method and

criticism on his approach see the following article: Gktrk, D. (January 2008). Su-

zuki Violin Teaching Method: Its Theory, Philosophy, and Criticism, Turkish Journal

of Music Education, year 1, vol. 1, number 1, http://www.tjme.org, ISSN: 1307-3389.

Comparing Two Contemporary Violin Teaching Methods: Suzuki And ... 403

May 2011 Vol:19 No:2 Kastamonu Education Journal

ter the World War II. According to Suzuki, talent is not innate but can be developed

by individual. He stated in his Nurtured by Love that Talent is no accident of birth

Man is grown with natural ability. A newborn child adjusts to his environment in or-

der to live, and various abilities are acquired in the process. (6) Suzuki also belie-

ved that talent was only a helpful element to develop the ability quicker than others.

Suzukis basic idea regarding to his pedagogy was the Mother Tongue method. He ob-

served that all Japanese children could speak their mother tongue, so he thought that

children could learn how to play violin in the same way. He observed the practicabi-

lity of this method as follows:

The environmental conditions and their infuence on the new-born baby as it

accustoms itself to the sounds of the mother tongue.

Teaching the child by constant repetition to utter its frst sound. Usually

mama mama mama and so on.

Everyday attitude of the parents after the baby starts to talk.

Natural progress through daily practice.

The skillfulness with which the parents build up enthusiasm in the child, and

the happiness of the child fnds in acquiring its new-found ability. (7).

In addition to Rollands String Research Project conducted and recorded at the

University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in Illinois (and supported by the Elemen-

tary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 1965), another project was also sponso-

red by ASTA in 1960s to bring the Suzuki Method to the attention of American string

teachers. Through this project, Shinichi Suzuki came to the United States to perform

for the ASTA conferences frst in 1964 and then in 1967. The two most important prin-

cipals by Suzuki from his Mother Tongue approach are as follows:

All children are encouraged to strive for their potential. Given the right envi-

ronment, any child can learn to do anything, and in particular, to play the vi-

olin. This musical environment includes supportive and actively involved pa-

rents, listening to good music from an early age (including the early violin pi-

eces), and good instrumental training.

Children can learn to do anything given enough repetitions in an encouraging

environment. As a result, practice is based upon the number of repetitions rat-

her than the quantity of time. (8).

In sum, the Suzuki approach in string teaching is based on listening. According

to this principle, listening is the basic activity that should be done daily by students.

Another principle is learning to read music by rote. Contrary to the more traditional

approach of learning a musical instrument, Suzukis Mother-Tongue method does not

use printed music with beginners. Instead, students listen to recordings of the litera-

Dilek GKTRK CARY... 404

Mays 2011 Cilt:19 No:2 Kastamonu Eitim Dergisi

ture they play. (9)

Another main idea of Suzukis string teaching pedagogy is parental involvement.

Suzuki believed in parents being at the center of his plan, and according to him mot-

hers are strongly encouraged participating lessons. Not only do they attend each pri-

vate lesson, ands monthly ensemble class, but they also actually learn to play the ins-

trument themselves, taking lessons during the frst few months when the child is to

listen to the recordings. When the child begins to take lessons, the mothers take no-

tes, study the manuals, and practice daily with the child at home, basing their help on

constant encouragement and patient repetition. (10). Indeed, repetition is the main

factor of achievement in Suzuki philosophy in string teaching. Repetition is crucial

for success in the Suzuki approach. After learning a composition, students must conti-

nue to review it, for Suzuki maintains that in ideal practice working for perfection on

the previous piece is the most important point for cultivating abilities. (11). Motiva-

tion concept is also very important in Suzuki approach. Encouraging students through

constructive support and stimulation, for instance Very good. Can you do better? is

the basic Suzuki formula (12).

3. Paul Rolland (1911-1978) and Rolland Method

Get them started right and aim them in the right direction and they will reach the

top . . . It is a fallacy to believe that the careful teaching of fundamentals will slow

down the pupil . . . Most elements of string playing can be introduced, in embryonic

form of course, during the frst year of instruction, and refned thereafter . . . One wo-

uld be quite surprised at what pupils can be started on during the frst and second ye-

ars . . . Music educators should strive to develop players who not only play in tune

with a good sound but who also feel comfortable and happy in so doing, and who use

well coordinated movements without excessive tension as they play . . . It is of pa-

ramount importance to develop a well balanced stance, balanced right and left arms,

and a balanced hold . . . Good balance is the key to effcient movements . . . A small

child can be taught to play with a beautiful tone and sonority by the use of good ba-

lance of the body and by avoiding static tensions in his movements . . . Stressed is fre-

edom of movement; trying to inculcate the pupil with a feeling of kinesthesia, a fee-

ling of lightness, both with the bow and the instrument . . . naturalness, naturalness,

natural- ness . . . (13)

Paul Rolland (1911-1978) was born in Hungary and trained in Europe. After co-

ming to the United States in the 1930s, he became a professor at the University of Il-

linois. He began to develop his string pedagogy in the 1950s. Rolland based his pe-

dagogy on the similarity of natural everyday movements to the motions required for

string playing. The word motion defnes the operative and often overlooked mode

of thought. (14). In his project, Young beginning string players were recruited from

the Urbana Public Schools, in the Illinois town where Rolland resided. Rolland and

Comparing Two Contemporary Violin Teaching Methods: Suzuki And ... 405

May 2011 Vol:19 No:2 Kastamonu Education Journal

his research associates taught approximately one hundred students for a two-year tri-

al, using the principles that Rolland had developed over the course of his teaching ca-

reer. Out of the project came a book called The Teaching of Action in String Playing

(1974). This book was designed and developed to help classroom string teachers te-

ach movements conducive to good string playing in a group setting. Rolland produ-

ced a set of illustrative flms to accompany the text of the book. (15). His vibrato and

shifting techniques are still popular today. According to Rolland Teaching, and the-

refore learning, occurs in two channels: Developmental and Remedial. New skills,

new knowledge should be introduced, and impressions already gained must be deepe-

ned, and constantly refned. Of the two channels, the frst one is always more popular

with the student, and the teacher should guard against being carried away by progress

which is too fast and without real substance and quality. (16).

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the similarities and differences were discussed between the two

string methods.

Similarities between Suzuki and Rolland methods

Similarities between Rolland and Suzuki methods are as follows:

When Suzuki toured the United States in 1964, Rolland received a grant to

create a flm Suzuki Teaches American Mothers and Their Children, and, con-

sequently, he was infuenced by him. Many of Rollands ideas are related to

the teaching of Shinichi Suzuki. Such as matters as the rote-note approach,

a strong concern for correct playing posture, constant review and refnement

of a relatively small but constantly growing repertoire, the use of short, rapid

bow strokes at frst, and the concept of an early bow hold are found in the te-

aching of both Suzuki and Rolland. (17). Moreover, their approaches on te-

aching vibrato are mostly similar.

In Suzuki teaching the most important point is technique and tone, and the

reproduction of sounds. Since Suzuki teachers often go through a rigorous

certifcation process, parents should ask about the teachers level of training

and expertise. On the other hand, teachers using strict Rolland approach will

spend a great deal of time focusing on the quality of the sound and also on

students technique, which will involve students doing repetitive physical ac-

tions to release the tension in violin lessons.

Differences between Suzuki and Rolland methods

Differences between Rolland and Suzuki methods are as follows:

Although Suzuki philosophy is not based on musical talent, Paul Rollands

method does not mention anything about inborn ability or does not indicate

Dilek GKTRK CARY... 406

Mays 2011 Cilt:19 No:2 Kastamonu Eitim Dergisi

that every child can play the violin.

Parental involvement is a very important part of Suzukis teaching. As one of

the most important parts of Suzukis teaching, parents are expected to attend

both individual and group lessons. They also have to practice with the child

at home every day. Moreover, parents are expected to take notes at lessons to

help their children to practice at home, and they should be in constant con-

tact with the teacher. On the other hand, involvement of parents is not requ-

ired in Rollands approach even though they are encouraged to be supporti-

ve of children. Parental involvement is left to the preference of parents and/

or teacher.

In the Suzuki method, reading music becomes a focus later. During the frst

year of violin instruction, students will be introduced to music reading thro-

ugh the use of letters, and they move to read basic staff notation in one year.

Rolland method does not require a similar way to teach how to read music.

Students begin to read music in the early stages of the instruction in Rollands

approach.

Weekly group lessons are mostly required in addition to individual lessons in

Suzuki method. Group lessons are not required in Rollands approach.

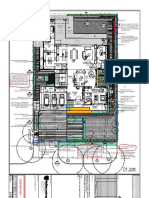

Both methods offer early bow-hold; however, each of them requests a diffe-

rent style. For example, Suzuki approach offers the early bow hold as holding

at the normal place of the bow but placing the thumb not the inside but the

outside of the frog (see Picture 1 below). Rolland method offers the early bow

hold as holding at the balance point (see Picture 2 below).

Picture 1. Suzuki bow hold for beginners Picture 2. Rolland bow hold for beginners

Rest positions differ from each other in each method. In Suzuki approach, stu-

Comparing Two Contemporary Violin Teaching Methods: Suzuki And ... 407

May 2011 Vol:19 No:2 Kastamonu Education Journal

dent holds the violin under the arm but in Rolland style the violin is held like

a guitar.

In Suzuki pedagogy, tapes are used for each fnger on the fngerboard. Yet,

in Rollands method only a dot is used on the middle part of the fngerboard.

Both hands (bow and left hand) are used together in the frst lesson in Suzu-

ki approach. In Rolland Method, the left hand position is taught frst (before

using the bow) through plucking and playing pizzicato. Once students excel

in left hand technique they can begin to use the bow.

Shifting technique is another difference between two string teaching methods.

According to Suzuki, beginning with the fourth position is the easiest task

in shifting for students. On the other hand, Rollands method offers shifting

to third or ffth positions as the simplest approach for students. In addition,

Rollands system includes broader information and more examples of shifting

techniques than Suzukis method.

The work of Rolland and Suzuki and the adoption of their materials for use in the

string class have had a tremendous impact on raising the quality of string programs

in the schools. Also, through continued efforts by ASTA, NSOA, and MENC, string

programs are now appearing in schools where they had disappeared or never exis-

ted before. (18). For the future of string education in the world we can continue to

improve our methods, approaching them, it is hoped, with the same thoroughness and

thoughtfulness that has never been handed down us. (19). With the use of these two

string methods in Turkey, string education can start early and better string instruction

can be provided. As a recommendation, these two methods should be adopted in Tur-

key and string teachers should be educated through workshops (either abroad or by

inviting experts in these areas). If we desire to have a better quality in string educati-

on in Turkey (so that we can train well-equipped musicians) we should start adopting

new methods from other countries. As the author, I believe that the United States is a

good example that we can follow regarding this issue, and I believe that true conf-

dence and peace only come with borrowing and learning experiences from each other

along with following nationally distinct paths. (20).

5. References

1. Smith, C. M. History of Public School String Education. Unpublished book, Chapter I.

2. Smith, C. M. History of Public School String Education. Unpublished book, Chapter I.

3. Smith, C. M. History of Public School String Education. Unpublished book, Chapter I.

4. http://www.stringpedagogy.com/en/public/vol_1/01_000.htm 10.12.2006da alnd.

5. http://www.stringpedagogy.com/en/public/vol_1/01_000.htm 10.12.2006da alnd.

6. Suzuki, S. Nurtured by Love, New York, Exposition Press, 1969.

Dilek GKTRK CARY... 408

Mays 2011 Cilt:19 No:2 Kastamonu Eitim Dergisi

7. Starr, W. The Suzuki Violinist: A Guide for Teachers and Parents, Tennessee, Kingston El-

lis Press, 1976.

8. http://www.stringpedagogy.com/en/public/vol_1/01_000.htm 10.12.2006da alnd.

9. Carpenter, S. L. Shinichi Suzuki and His Mother-Tongue Approach to Music Education

in the United States, Unpublished Master of Fine Arts Thesis, University of Florida, Gai-

nesville, Florida, 1988.

10. Kendall, J. D. The Suzuki Violin Method in American Music Education: What the Ameri-

can Music Educator Should Know About Shinichi Suzuki, MENC, 1973.

11. Starr, W. The Suzuki Violinist: A Guide for Teachers and Parents, Tennessee, Kingston El-

lis Press, 1976.

12. Starr, W. The Suzuki Violinist: A Guide for Teachers and Parents, Tennessee, Kingston El-

lis Press, 1976.

13. Eisele, M. J. Refections on Paul Rolland, http://web55.mysecureserver.com/astawebcom/

resources/WOPR.pdf 05.01.2010da alnd.

14. http://www.alexandercenter.com/pa/strings.html 10.12.2006da alnd.

15. http://www.alexandercenter.com/pa/strings.html 10.12.2006da alnd.

16. Rolland, P. & Mutscler, M. The Teaching of Action in String Playing, Illinois, Boosey &

Hawkes, 1974.

17. Fischbach, G. F. A Comprehensive Performance Project in Violin Literature and an Essay

Consisting of a Comparative Study of the Teaching Methods of Samuel Applebaum and

Paul Rolland, DMA Thesis, University of Iowa, 1972.

18. http://www.uvm.edu/~mhopkins/?Page=history.html 12.10.2006da alnd.

19. Erwin, J. Roots, Highlights from the American String Teacher-School Teachers Forum

(1984-1994), U. S. A, American String Teachers Association, 1996.

20. Gktrk, D. Historical development of public school string education in the United States

and connections with Turkey, Uluda niversitesi Eitim Fakltesi Dergisi, Cilt: 22, No:

2, Bursa, Aralk 2009, http://kutuphane.uludag.edu.tr/Univder/uufader.htm 12.01.2010da

alnd.

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Accordion PiecesDocument161 pagesAccordion PiecesMarius Buta100% (2)

- Accordion BookDocument164 pagesAccordion BookAshley SanchezNo ratings yet

- Country Blues GuitarDocument21 pagesCountry Blues GuitarAshley Sanchez100% (4)

- Deniz Sarı İtç Ve Otç'de Batı Anadolu'Nun Kültürel Ve Siyasal GelişimiDocument138 pagesDeniz Sarı İtç Ve Otç'de Batı Anadolu'Nun Kültürel Ve Siyasal GelişimiAshley SanchezNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Social ScienceDocument15 pagesInternational Journal of Social ScienceAshley SanchezNo ratings yet

- 19 2 4Document8 pages19 2 4Ashley SanchezNo ratings yet

- ATMM 2013 Program BookletDocument23 pagesATMM 2013 Program BookletAshley SanchezNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Faq On Ivr 3d SecureDocument2 pagesFaq On Ivr 3d SecureRio PopoffNo ratings yet

- WL100-GA - Rev 01Document1 pageWL100-GA - Rev 01affendy roynNo ratings yet

- UK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationDocument11 pagesUK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationAxror TojibayevNo ratings yet

- Design of Steel StructuresDocument4 pagesDesign of Steel StructuresmysteryNo ratings yet

- ST Paul's CathedralDocument21 pagesST Paul's CathedralJason Tiongco100% (1)

- High-efficiency low-profile DC-DC converter for digital car audioDocument2 pagesHigh-efficiency low-profile DC-DC converter for digital car audiokrishnandrkNo ratings yet

- "Super Blues" Scales For Leveling-Up Your Jazz Blues ImprovDocument5 pages"Super Blues" Scales For Leveling-Up Your Jazz Blues ImprovShreyans Jain100% (4)

- Namakkal RWDocument28 pagesNamakkal RWabarajithan1987No ratings yet

- 7 On NarratologyDocument25 pages7 On NarratologymohamedelbehiNo ratings yet

- GMB Isp PDFDocument29 pagesGMB Isp PDFmarkNo ratings yet

- 1 - Camera - Operations - How To Maintain A Camera and Roles of A Camera OperatorDocument22 pages1 - Camera - Operations - How To Maintain A Camera and Roles of A Camera Operator18bumby JohnNo ratings yet

- 2 NDDocument450 pages2 NDscoop otiblackNo ratings yet

- Project 5 Unit 4 GrammarDocument2 pagesProject 5 Unit 4 GrammarŠtefan Viktor100% (1)

- SherlockDocument4 pagesSherlockdash-watson-3695No ratings yet

- A+ Guide To Hardware, 4eDocument62 pagesA+ Guide To Hardware, 4eepriyaa100% (4)

- CCM RS232 Cable Wire ConnectionDocument2 pagesCCM RS232 Cable Wire Connectionlinkangjun0621No ratings yet

- First Crusade 10/1b - Edessa 2 - Turbessel and RavendelDocument15 pagesFirst Crusade 10/1b - Edessa 2 - Turbessel and RavendelWilliam HamblinNo ratings yet

- MT1 Ch18Document6 pagesMT1 Ch18api-19856023No ratings yet

- Zebra Gt820 Desktop Barcode PrinterDocument2 pagesZebra Gt820 Desktop Barcode PrinterAbi MartinezNo ratings yet

- Guitar Signal Processor/Foot Controller and Preamp: Owner's ManualDocument30 pagesGuitar Signal Processor/Foot Controller and Preamp: Owner's ManualRandy CarlyleNo ratings yet

- Amulet Book 8Document208 pagesAmulet Book 8Alma Guerra100% (1)

- Canon 5diii Pocket Guide 1.2Document4 pagesCanon 5diii Pocket Guide 1.2William R AmyotNo ratings yet

- Wheelchair Tennis Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesWheelchair Tennis Lesson Planapi-609121733No ratings yet

- Reported Speech ExercisesDocument4 pagesReported Speech ExercisesNTK KHUONGNo ratings yet

- Temporary Enchantment: by Barak BlackburnDocument6 pagesTemporary Enchantment: by Barak BlackburnAngel Belisle Jr.No ratings yet

- Kite FestivalDocument2 pagesKite FestivalSameer KhatriNo ratings yet

- Notorious ScreenplayDocument88 pagesNotorious Screenplaysagarrajaneni100% (1)

- AHD-DVR Operation InstructionsDocument67 pagesAHD-DVR Operation InstructionseurbaezNo ratings yet

- Mau To DelhiDocument2 pagesMau To DelhiRaju PatelNo ratings yet

- La Cabs: Presented By:-Akshita SrivastavaDocument11 pagesLa Cabs: Presented By:-Akshita SrivastavaPubg GamerNo ratings yet