Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Certificate of Election in Labor

Uploaded by

pacalnaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Certificate of Election in Labor

Uploaded by

pacalnaCopyright:

Available Formats

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 140518. December 16, 2004]

MANILA DIAMOND HOTEL EMPLOYEES UNION, petitioner, vs. THE

HON. COURT OF APPEALS, THE SECRETARY OF LABOR AND

EMPLOYMENT, and THE MANILA DIAMOND

HOTEL, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

AZCUNA, J .:

This petition for review of a decision of the Court of Appeals arose out of a

dispute between the Philippine Diamond Hotel and Resort, Inc. (Hotel),

owner of the Manila Diamond Hotel, and the Manila Diamond Hotel

Employees Union (Union). The facts are as follows:

On November 11, 1996, the Union filed a petition for a certification election

so that it may be declared the exclusive bargaining representative of the

Hotels employees for the purpose of collective bargaining. The petition was

dismissed by the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) on January

15, 1997. After a few months, however, on August 25, 1997, the Union sent a

letter to the Hotel informing it of its desire to negotiate for a collective

bargaining agreement.

[1]

In a letter dated September 11, 1997, the Hotels

Human Resources Department Manager, Mary Anne Mangalindan, wrote to

the Union stating that the Hotel cannot recognize it as the employees

bargaining agent since its petition for certification election had been earlier

dismissed by the DOLE.

[2]

On that same day, the Hotel received a letter from

the Union stating that they were not giving the Hotel a notice to bargain, but

that they were merely asking for the Hotel to engage in collective bargaining

negotiations with the Union for its members only and not for all the rank and

file employees of the Hotel.

[3]

On September 18, 1997, the Union announced that it was taking a strike

vote. A Notice of Strike was thereafter filed on September 29, 1997, with the

National Conciliation and Mediation Board (NCMB) for the Hotels alleged

refusal x x x to bargain and for alleged acts of unfair labor practice. The

NCMB summoned both parties and held a series of dialogues, the first of

which was on October 6, 1997.

On November 29, 1997, however, the Union staged a strike against the

Hotel. Numerous confrontations between the two parties followed, creating an

obvious strain between them. The Hotel claims that the strike was illegal and it

had to dismiss some employees for their participation in the allegedly illegal

concerted activity. The Union, on the other hand, accused the Hotel of

illegally dismissing the workers. What is pertinent to this case, however, is the

Order issued by the then Secretary of Labor and Employment Cresenciano B.

Trajano assuming jurisdiction over the labor dispute. A Petition for Assumption

of Jurisdiction was filed by the Union on April 2, 1998. Thereafter, the

Secretary of Labor and Employment issued an Order dated April 15, 1998, the

dispositive portion of which states:

WHEREFORE, premises considered[,] this Office CERTIFIES the labor dispute at

the Manila Diamond Hotel to the National Labor Relations Commission, for

compulsory arbitration, pursuant to Article 263 (g) of the Labor Code, as amended.

Accordingly, the striking officers and members of the Manila Diamond Hotel

Employees Union --- NUWHRAIN are hereby directed to return to work within

twenty-four (24) hours upon receipt of this Order and the Hotel to accept them back

under the same terms and conditions prevailing prior to the strike. The parties are

enjoined from committing any act that may exacerbate the situation.

The Union received the aforesaid Order on April 16, 1998 and its

members reported for work the next day, April 17, 1998. The Hotel, however,

refused to accept the returning workers and instead filed a Motion for

Reconsideration of the Secretarys Order.

On April 30, 1998, then Acting Secretary of Labor Jose M. Espaol, issued

the disputed Order, which modified the earlier one issued by Secretary

Trajano. Instead of an actual return to work, Acting Secretary Espaol

directed that the strikers be reinstated only in the payroll.

[4]

The Union moved

for the reconsideration of this Order, but its motion was denied on June 25,

1998. Hence, it filed before this Court on August 26, 1998, a petition

for certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court alleging grave abuse of

discretion on the part of the Secretary of Labor for modifying its earlier order

and requiring instead the reinstatement of the employees in the payroll.

However, in a resolution dated July 12, 1999, this Court referred the case to

the Court of Appeals, pursuant to the principle embodied in National

Federation of Labor v. Laguesma.

[5]

On October 19, 1999, the Court of Appeals rendered a Decision

dismissing the Unions petition and affirming the Secretary of Labors Order

for payroll reinstatement. The Court of Appeals held that the challenged order

is merely an error of judgment and not a grave abuse of discretion and that

payroll reinstatement is not prohibited by law, but may be called for under

certain circumstances.

[6]

Hence, the Union now stands before this Court maintaining that:

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS GRIEVIOUSLY ERRED IN RULING

THAT THE SECRETARY OF LABORS UNAUTHORIZED ORDER OF MERE

PAYROLL REINSTATEMENT IS NOT GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION

[7]

The petition has merit.

The Court of Appeals based its decision on this Courts ruling in University

of Santo Tomas (UST) v. NLRC.

[8]

There, the Secretary assumed jurisdiction

over the labor dispute between striking teachers and the university. He

ordered the striking teachers to return to work and the university to accept

them under the same terms and conditions. However, in a subsequent order,

the NLRC provided payroll reinstatement for the striking teachers as an

alternative remedy to actual reinstatement. True, this Court held therein that

the NLRC did not commit grave abuse of discretion in providing for the

alternative remedy of payroll reinstatement. This Court found that it was

merely an error of judgment, which is not correctible by a special civil action

for certiorari. The NLRC was only trying its best to work out a satisfactory ad

hoc solution to a festering and serious problem.

However, this Court notes that the UST ruling was made in the light of one

very important fact: the teachers could not be given back their academic

assignments since the order of the Secretary for them to return to work was

given in the middle of the first semester of the academic year. The NLRC

was, therefore, faced with a situation where the striking teachers were entitled

to a return to work order, but the university could not immediately reinstate

them since it would be impracticable and detrimental to the students to

change teachers at that point in time.

In the present case, there is no showing that the facts called for payroll

reinstatement as an alternative remedy. A strained relationship between the

striking employees and management is no reason for payroll reinstatement in

lieu of actual reinstatement. Petitioner correctly points out that labor disputes

naturally involve strained relations between labor and management, and that

in most strikes, the relations between the strikers and the non-strikers will

similarly be tense.

[9]

Bitter labor disputes always leave an aftermath of strong

emotions and unpleasant situations. Nevertheless, the government must still

perform its function and apply the law, especially if, as in this case, national

interest is involved.

After making the distinction between UST and the present case, this Court

now addresses the issue of whether the Court of Appeals erred in ruling that

the Secretary did not commit any grave abuse of discretion in ordering payroll

reinstatement in lieu of actual reinstatement. This question is answered by

the nature of Article 263(g). As a general rule, the State encourages an

environment wherein employers and employees themselves must deal with

their problems in a manner that mutually suits them best. This is the basic

policy embodied in Article XIII, Section 3 of the Constitution,

[10]

which was

further echoed in Article 211 of the Labor Code.

[11]

Hence, a voluntary, instead

of compulsory, mode of dispute settlement is the general rule.

However, Article 263, paragraph (g) of the Labor Code, which allows the

Secretary of Labor to assume jurisdiction over a labor dispute involving an

industry indispensable to the national interest, provides an exception:

(g) When, in his opinion, there exists a labor dispute causing or likely to cause a

strike or lockout in an industry indispensable to the national interest, the Secretary of

Labor and Employment may assume jurisdiction over the dispute and decide it or

certify the same to the Commission for compulsory arbitration. Such assumption or

certification shall have the effect of automatically enjoining the intended or

impending strike or lockout as specified in the assumption or certification order. If

one has already taken place at the time of assumption or certification, all striking or

locked out employees shall immediately return to work and the employer shall

immediately resume operations and readmit all workers under the same terms and

conditions prevailing before the strike or lockout. x x x

This provision is viewed as an exercise of the police power of the State. A

prolonged strike or lockout can be inimical to the national economy and,

therefore, the situation is imbued with public necessity and involves the right

of the State and the public to self-protection.

[12]

Under Article 263(g), all workers must immediately return to work and all

employers must readmit all of them under the same terms and conditions

prevailing before the strike or lockout. This Court must point out that the law

uses the precise phrase of under the same terms and conditions, revealing

that it contemplates only actual reinstatement. This is in keeping with the

rationale that any work stoppage or slowdown in that particular industry can

be inimical to the national economy. It is clear that Article 263(g) was not

written to protect labor from the excesses of management, nor was it written

to ease management from expenses, which it normally incurs during a work

stoppage or slowdown. It was an error on the part of the Court of Appeals to

view the assumption order of the Secretary as a measure to protect the

striking workers from any retaliatory action from the Hotel. This Court

reiterates that this law was written as a means to be used by the State to

protect itself from an emergency or crisis. It is not for labor, nor is it for

management.

It is, therefore, evident from the foregoing that the Secretarys subsequent

order for mere payroll reinstatement constitutes grave abuse of discretion

amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. Indeed, this Court has always

recognized the great breadth of discretion by the Secretary once he

assumes jurisdiction over a labor dispute. However, payroll reinstatement in

lieu of actual reinstatement is a departure from the rule in these cases and

there must be showing of special circumstances rendering actual

reinstatement impracticable, as in the UST case aforementioned, or otherwise

not conducive to attaining the purpose of the law in providing for assumption

of jurisdiction by the Secretary of Labor and Employment in a labor dispute

that affects the national interest. None appears to have been established in

this case. Even in the exercise of his discretion under Article 236(g), the

Secretary must always keep in mind the purpose of the law. Time and again,

this Court has held that when an official by-passes the law on the asserted

ground of attaining a laudable objective, the same will not be maintained if the

intendment or purpose of the law would be defeated.

[13]

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED and the assailed Decision of the

Court of Appeals dated October 19, 1999 is REVERSED and SET ASIDE.

The Order dated April 30, 1998 issued by the Secretary of Labor and

Employment modifying the earlier Order dated April 15, 1998, is likewise SET

ASIDE. No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., (Chairman), Ynares-Santiago, and Carpio, JJ., concur.

Quisumbing, J., no part.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

ALABANG COUNTRY CLUB, INC., G.R. No. 170287

Petitioner,

Present:

- versus -

QUISUMBING, J., Chairperson,

CARPIO MORALES,

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS AZCUNA,

COMMISSION, ALABANG TINGA, and

COUNTRY CLUB INDEPENDENT VELASCO, JR., JJ.

EMPLOYEES UNION,

CHRISTOPHER PIZARRO,

MICHAEL BRAZA, and Promulgated:

NOLASCO CASTUERAS,

Respondents. February 14, 2008

x-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------x

D E C I S I O N

VELASCO, JR., J .:

Petitioner Alabang Country Club, Inc. (Club) is a domestic non-profit

corporation with principal office at Country Club Drive, Ayala

Alabang, Muntinlupa City. Respondent Alabang Country Club Independent

Employees Union (Union) is the exclusive bargaining agent of the Clubs rank-

and-file employees. In April 1996, respondents Christopher Pizarro, Michael

Braza, and Nolasco Castueras were elected Union President, Vice-President, and

Treasurer, respectively.

On June 21, 1999, the Club and the Union entered into a Collective

Bargaining Agreement (CBA), which provided for a Union shop and maintenance

of membership shop.

The pertinent parts of the CBA included in Article II on Union Security

read, as follows:

ARTICLE II

UNION SECURITY

SECTION 1. CONDITION OF EMPLOYMENT. All regular rank-and-

file employees, who are members or subsequently become members of the

UNION shall maintain their membership in good standing as a condition for their

continued employment by the CLUB during the lifetime of this Agreement or any

extension thereof.

SECTION 2. [COMPULSORY] UNION MEMBERSHIP FOR NEW

REGULAR RANK-AND-FILE EMPLOYEES

a) New regular rank-and-file employees of the Club shall join

the UNION within five (5) days from the date of their appointment as regular

employees as a condition for their continued employment during the lifetime

of this Agreement, otherwise, their failure to do so shall be a ground for

dismissal from the CLUB upon demand by the UNION.

b) The Club agrees to furnish the UNION the names of all new probationary and

regular employees covered by this Agreement not later than three (3) days

from the date of regular appointment showing the positions and dates of

hiring.

x x x x

SECTION 4. TERMINATION UPON UNION DEMAND. Upon written

demand of the UNION and after observing due process, the Club shall dismiss a

regular rank-and-file employee on any of the following grounds:

(a) Failure to join the UNION within five (5) days from the time of

regularization;

(b) Resignation from the UNION, except within the period allowed

by law;

(c) Conviction of a crime involving moral turpitude;

(d) Non-payment of UNION dues, fees, and assessments;

(e) Joining another UNION except within the period allowed by law;

(f) Malversation of union funds;

(g) Actively campaigning to discourage membership in the UNION;

and

(h) Inflicting harm or injury to any member or officer of the UNION.

It is understood that the UNION shall hold the CLUB free and harmless

[sic] from any liability or damage whatsoever which may be imposed upon it by

any competent judicial or quasi-judicial authority as a result of such dismissal and

the UNION shall reimburse the CLUB for any and all liability or damage it may

be adjudged.

[1]

(Emphasis supplied.)

Subsequently, in July 2001, an election was held and a new set of officers

was elected. Soon thereafter, the new officers conducted an audit of the Union

funds. They discovered some irregularly recorded entries, unaccounted expenses

and disbursements, and uncollected loans from the Union funds. The Union

notified respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras of the audit results and asked

them to explain the discrepancies in writing.

[2]

Thereafter, on October 6, 2001, in a meeting called by the Union,

respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras explained their side. Braza denied any

wrongdoing and instead asked that the investigation be addressed to Castueras,

who was the Union Treasurer at that time. With regard to his unpaid loans, Braza

claimed he had been paying through monthly salary deductions and said the Union

could continue to deduct from his salary until full payment of his loans, provided

he would be reimbursed should the result of the initial audit be proven wrong by a

licensed auditor. With regard to the Union expenses which were without receipts,

Braza explained that these were legitimate expenses for which receipts were not

issued, e.g. transportation fares, food purchases from small eateries, and food and

transportation allowances given to Union members with pending complaints with

the Department of Labor and Employment, the National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC), and the fiscals office. He explained that though there were

no receipts for these expenses, these were supported by vouchers and itemized as

expenses. Regarding his unpaid and unliquidated cash advances amounting to

almost PhP 20,000, Braza explained that these were not actual cash advances but

payments to a certain Ricardo Ricafrente who had loaned PhP 200,000 to

the Union.

[3]

Pizarro, for his part, blamed Castueras for his unpaid and uncollected loan

and cash advances. He claimed his salaries were regularly deducted to pay his loan

and he did not know why these remained unpaid in the records. Nonetheless, he

likewise agreed to continuous salary deductions until all his accountabilities were

paid.

[4]

Castueras also denied any wrongdoing and claimed that the irregular entries

in the records were unintentional and were due to inadvertence because of his

voluminous work load. He offered that his unpaid personal loan of PhP 27,500

also be deducted from his salary until the loans were fully paid. Without admitting

any fault on his part, Castueras suggested that his salary be deducted until the

unaccounted difference between the loans and the amount collected amounting to a

total of PhP 22,000 is paid.

[5]

Despite their explanations, respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras were

expelled from the Union, and, on October 16, 2001, were furnished individual

letters of expulsion for malversation of Union funds.

[6]

Attached to the letters were

copies of thePanawagan ng mga Opisyales ng Unyon signed by 37 out of 63

Union members and officers, and a Board of Directors Resolution

[7]

expelling

them from the Union.

In a letter dated October 18, 2001, the Union, invoking the Security Clause

of the CBA, demanded that the Club dismiss respondents Pizarro, Braza, and

Castueras in view of their expulsion from the Union.

[8]

The Club required the three

respondents to show cause in writing within 48 hours from notice why they should

not be dismissed. Pizarro and Castueras submitted their respective written

explanations on October 20, 2001, while Braza submitted his explanation the

following day.

During the last week of October 2001, the Clubs general manager called

respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras for an informal conference inquiring

about the charges against them. Said respondents gave their explanation and

asserted that the Union funds allegedly malversed by them were even over the total

amount collected during their tenure as Union officersPhP 120,000 for Braza,

PhP 57,000 for Castueras, and PhP 10,840 for Pizarro, as against the total

collection from April 1996 to December 2001 of only PhP 102,000. They claimed

the charges are baseless. The general manager announced he would conduct a

formal investigation.

Nonetheless, after weighing the verbal and written explanations of the three

respondents, the Club concluded that said respondents failed to refute the validity

of their expulsion from the Union. Thus, it was constrained to terminate the

employment of said respondents. On December 26, 2001, said respondents

received their notices of termination from the Club.

[9]

Respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras challenged their dismissal from

the Club in an illegal dismissal complaint docketed as NLRC-NCR Case No. 30-

01-00130-02 filed with the NLRC, National Capital Region Arbitration Branch. In

his January 27, 2003 Decision,

[10]

the Labor Arbiter ruled in favor of the Club, and

found that there was justifiable cause in terminating said respondents. He

dismissed the complaint for lack of merit.

On February 21, 2003, respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras filed an

Appeal docketed as NLRC NCR CA No. 034601-03 with the NLRC.

On February 26, 2004, the NLRC rendered a Decision

[11]

granting the

appeal, the fallo of which reads:

WHEREFORE, finding merit in the Appeal, judgment is hereby rendered

declaring the dismissal of the complainants illegal. x x x Alabang Country Club,

Inc. and Alabang Country Club Independent Union are hereby ordered to reinstate

complainants Christopher Pizarro, Nolasco Castueras and Michael Braza to their

former positions without loss of seniority rights and other privileges with full

backwages from the time they were dismissed up to their actual reinstatement.

SO ORDERED.

The NLRC ruled that there was no justifiable cause for the termination of

respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras. The commissioners relied heavily on

Section 2, Rule XVIII of the Rules Implementing Book V of the Labor Code. Sec.

2 provides:

SEC. 2. Actions arising from Article 241 of the Code. Any action arising

from the administration or accounting of union funds shall be filed and disposed

of as an intra-union dispute in accordance with Rule XIV of this Book.

In case of violation, the Regional or Bureau Director shall order the

responsible officer to render an accounting of funds before the general

membership and may, where circumstances warrant, mete the appropriate penalty

to the erring officer/s, including suspension or expulsion from the union.

[12]

According to the NLRC, said respondents expulsion from the Union was

illegal since the DOLE had not yet made any definitive ruling on their liability

regarding the administration of the Unions funds.

The Club then filed a motion for reconsideration which the NLRC denied in

its June 20, 2004 Resolution.

[13]

Aggrieved by the Decision and Resolution of the NLRC, the Club filed a

Petition for Certiorari which was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 86171 with the

Court of Appeals (CA).

The CA Upheld the NLRC Ruling

that the Three Respondents were Deprived Due Process

On July 5, 2005, the appellate court rendered a Decision,

[14]

denying the

petition and upholding the Decision of the NLRC. The CAs Decision focused

mainly on the Clubs perceived failure to afford due process to the three

respondents. It found that said respondents were not given the opportunity to be

heard in a separate hearing as required by Sec. 2(b), Rule XXIII, Book V of the

Omnibus Rules Implementing the Labor Code, as follows:

SEC. 2. Standards of due process; requirements of notice.In all cases of

termination of employment, the following standards of due process shall be

substantially observed:

For termination of employment based on just causes as defined in Article

282 of the Code:

x x x x

(b) A hearing or conference during which the employee concerned,

with the assistance of counsel if the employee so desires, is given opportunity to

respond to the charge, present his evidence or rebut the evidence presented

against him.

The CA also said the dismissal of the three respondents was contrary to the

doctrine laid down in Malayang Samahan ng mga Manggagawa sa M. Greenfield

v. Ramos (Malayang Samahan), where this Court ruled that even on the

assumption that the union had valid grounds to expel the local union officers, due

process requires that the union officers be accorded a separate hearing by the

employer company.

[15]

In a Resolution

[16]

dated October 20, 2005, the CA denied the Clubs motion

for reconsideration.

The Club now comes before this Court with these issues for our resolution,

summarized as follows:

1. Whether there was just cause to dismiss private respondents, and whether

they were afforded due process in accordance with the standards provided

for by the Labor Code and its Implementing Rules.

2. Whether or not the CA erred in not finding that the NLRC committed

grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction when

it ruled that respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras were illegally

expelled from the Union.

3. Whether the case of Agabon vs. NLRC

[17]

should be applied to this case.

4. Whether that in the absence of bad faith and malice on the part of the

Club, the Union is solely liable for the termination from employment of

said respondents.

The main issue is whether the three respondents were illegally dismissed and

whether they were afforded due process.

The Club avers that the dismissal of the three respondents was in accordance

with the Union security provisions in their CBA. The Club also claims that the

three respondents were afforded due process, since the Club conducted an

investigation separate and independent from that conducted by the Union.

Respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras, on the other hand, contend that

the Club failed to conduct a separate hearing as prescribed by Sec. 2(b), Rule

XXIII, Book V of the implementing rules of the Code.

First, we resolve the legality of the three respondents dismissal from the

Club.

Valid Grounds for Termination

Under the Labor Code, an employee may be validly terminated on the

following grounds: (1) just causes under Art. 282; (2) authorized causes under Art.

283; (3) termination due to disease under Art. 284; and (4) termination by the

employee or resignation under Art. 285.

Another cause for termination is dismissal from employment due to the

enforcement of the union security clause in the CBA. Here, Art. II of the CBA on

Union security contains the provisions on the Union shop and maintenance of

membership shop. There is union shop when all new regular employees are

required to join the union within a certain period as a condition for their continued

employment. There is maintenance of membership shop when employees who are

union members as of the effective date of the agreement, or who thereafter become

members, must maintain union membership as a condition for continued

employment until they are promoted or transferred out of the bargaining unit or the

agreement is terminated.

[18]

Termination of employment by virtue of a union

security clause embodied in a CBA is recognized and accepted in our

jurisdiction.

[19]

This practice strengthens the union and prevents disunity in the

bargaining unit within the duration of the CBA. By preventing member

disaffiliation with the threat of expulsion from the union and the consequent

termination of employment, the authorized bargaining representative gains more

numbers and strengthens its position as against other unions which may want to

claim majority representation.

In terminating the employment of an employee by enforcing the union

security clause, the employer needs only to determine and prove that: (1) the union

security clause is applicable; (2) the union is requesting for the enforcement of the

union security provision in the CBA; and (3) there is sufficient evidence to support

the unions decision to expel the employee from the union. These requisites

constitute just cause for terminating an employee based on the CBAs union

security provision.

The language of Art. II of the CBA that the Union members must maintain

their membership in good standing as a conditionsine qua non for their continued

employment with the Club is unequivocal. It is also clear that upon demand by

the Union and after due process, the Club shall terminate the employment of a

regular rank-and-file employee who may be found liable for a number of offenses,

one of which is malversation of Union funds.

[20]

Below is the letter sent to respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras,

informing them of their termination:

On October 18, 2001, the Club received a letter from the Board of

Directors of the Alabang Country Club Independent Employees Union(Union)

demanding your dismissal from service by reason of your alleged commission of

act of dishonesty, specifically malversation of union funds. In support thereof, the

Club was furnished copies of the following documents:

1. A letter under the subject Result of Audit dated September 14, 2001

(receipt of which was duly acknowledged from your end), which

required you to explain in writing the charges against you (copy

attached);

2. The Unions Board of Directors Resolution dated October 2, 2001,

which explained that the Union afforded you an opportunity to explain

your side to the charges;

3. Minutes of the meeting of the Unions Board of Directors wherein an

administrative investigation of the case was conducted last October 6,

2001; and

4. The Unions Board of Directors Resolution dated October 15, 2001

which resolved your expulsion from the Union for acts of dishonesty

and malversation of union funds, which was duly approved by the

general membership.

After a careful evaluation of the evidence on hand vis--vis a thorough

assessment of your defenses presented in your letter-explanation dated October 6,

2001 of which you also expressed that you waived your right to be present during

the administrative investigation conducted by the Unions Board of Directors on

October 6, 2001, Management has reached the conclusion that there are

overwhelming reasons to consider that you have violated Section 4(f) of the CBA,

particularly on the grounds of malversation of union funds. The Club has

determined that you were sufficiently afforded due process under the

circumstances.

Inasmuch as the Club is duty-bound to comply with its obligation

under Section 4(f) of the CBA, it is unfortunate that Management is left with no

other recourse but to consider your termination from service effective upon your

receipt thereof. We wish to thank you for your services during your employment

with the Company. It would be more prudent that we just move on independently

if only to maintain industrial peace in the workplace.

Be guided accordingly.

[21]

Gleaned from the above, the three respondents were expelled from and by

the Union after due investigation for acts of dishonesty and malversation of Union

funds. In accordance with the CBA, the Union properly requested the Club,

through the October 18, 2001 letter

[22]

signed by Mario Orense, the Union

President, and addressed to Cynthia Figueroa, the Clubs HRD Manager, to

enforce the Union security provision in their CBA and terminate said

respondents. Then, in compliance with theUnions request, the Club reviewed the

documents submitted by the Union, requested said respondents to submit written

explanations, and thereafter afforded them reasonable opportunity to present their

side. After it had determined that there was sufficient evidence that said

respondents malversed Union funds, the Club dismissed them from their

employment conformably with Sec. 4(f) of the CBA.

Considering the foregoing circumstances, we are constrained to rule that

there is sufficient cause for the three respondents termination from employment.

Were respondents Pizarro, Braza, and Castueras accorded due process before

their employments were terminated?

We rule that the Club substantially complied with the due process

requirements before it dismissed the three respondents.

The three respondents aver that the Club violated their rights to due process

as enunciated in Malayang Samahan,

[23]

when it failed to conduct an independent

and separate hearing before they were dismissed from service.

The CA, in dismissing the Clubs petition and affirming the Decision of the

NLRC, also relied on the same case. We explained in Malayang Samahan:

x x x Although this Court has ruled that union security clauses embodied

in the collective bargaining agreement may be validly enforced and that

dismissals pursuant thereto may likewise be valid, this does not erode the

fundamental requirements of due process. The reason behind the enforcement of

union security clauses which is the sanctity and inviolability of contracts cannot

override ones right to due process.

[24]

In the above case, we pronounced that while the company, under a

maintenance of membership provision of the CBA, is bound to dismiss any

employee expelled by the union for disloyalty upon its written request, this

undertaking should not be done hastily and summarily. The company acts in bad

faith in dismissing a worker without giving him the benefit of a hearing.

[25]

We

cautioned in the same case that the power to dismiss is a normal prerogative of the

employer; however, this power has a limitation. The employer is bound to exercise

caution in terminating the services of the employees especially so when it is made

upon the request of a labor union pursuant to the CBA. Dismissals must not be

arbitrary and capricious. Due process must be observed in dismissing employees

because the dismissal affects not only their positions but also their means of

livelihood. Employers should respect and protect the rights of their employees,

which include the right to labor.

[26]

The CA and the three respondents err in relying on Malayang Samahan, as

its ruling has no application to this case. InMalayang Samahan, the union

members were expelled from the union and were immediately dismissed from the

company without any semblance of due process. Both the union and the company

did not conduct administrative hearings to give the employees a chance to explain

themselves. In the present case, the Club has substantially complied with due

process. The three respondents were notified that their dismissal was being

requested by the Union, and their explanations were heard. Then, the Club,

through its President, conferred with said respondents during the last week of

October 2001. The three respondents were dismissed only after the Club reviewed

and considered the documents submitted by the Union vis--vis the written

explanations submitted by said respondents. Under these circumstances, we find

that the Club had afforded the three respondents a reasonable opportunity to be

heard and defend themselves.

On the applicability of Agabon, the Club points out that the CA ruled that

the three respondents were illegally dismissed primarily because they were not

afforded due process. We are not unaware of the doctrine enunciated

in Agabon that when there is just cause for the dismissal of an employee, the lack

of statutory due process should not nullify the dismissal, or render it illegal or

ineffectual, and the employer should indemnify the employee for the violation of

his statutory rights.

[27]

However, we find that we could not apply Agabon to this

case as we have found that the three respondents were validly dismissed and were

actually afforded due process.

Finally, the issue that since there was no bad faith on the part of the Club,

the Union is solely liable for the termination from employment of the three

respondents, has been mooted by our finding that their dismissal is valid.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Decision dated July 5, 2005 of

the CA and the Decision dated February 26, 2004of the NLRC are

hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The Decision dated January 27, 2003 of

the Labor Arbiter in NLRC-NCR Case No. 30-01-00130-02 is

hereby REINSTATED.

No costs.

SO ORDERED.

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

SECOND DIVISION

YOLITO FADRIQUELAN, ARTURO G.R. No. 178409

EGUNA, ARMANDO MALALUAN,

DANILO ALONSO, ROMULO

DIMAANO, ROEL MAYUGA,

WILFREDO RIZALDO, ROMEO

SUICO, DOMINGO ESCAMILLAS

and DOMINGO BAUTRO,

Petitioners, Present:

CARPIO, J., Chairperson,

- versus - NACHURA,

PERALTA,

ABAD, and

MENDOZA, JJ.

MONTEREY FOODS CORPORATION,

Respondent.

x ------------------------------------------------ x

MONTEREY FOODS CORPORATION, G.R. No. 178434

Petitioner,

- versus -

BUKLURAN NG MGA MANGGAGAWA

SA MONTEREY-ILAW AT BUKLOD NG

MANGGAGAWA, YOLITO FADRIQUELAN,

CARLITO ABACAN, ARTURO EGUNA,

DANILO ROLLE, ALBERTO CASTILLO,

ARMANDO MALALUAN, DANILO

ALFONSO, RUBEN ALVAREZ, ROMULO

DIMAANO, ROEL MAYUGA, JUANITO

TENORIO, WILFREDO RIZALDO, JOHN

ASOTIGUE, NEMESIO AGTAY, ROMEO

SUICO, DOMINGO ESCAMILLAS Promulgated:

and DOMINGO BAUTRO,

Respondents. June 8, 2011

x --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- x

DECI SI ON

ABAD, J .:

These cases are about the need to clearly identify, for establishing liability,

the union officers who took part in the illegal slowdown strike after the

Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) Secretary assumed jurisdiction

over the labor dispute.

The Facts and the Case

On April 30, 2002 the three-year collective bargaining agreement or CBA

between the union Bukluran ng Manggagawa sa Monterey-Ilaw at Buklod ng

Manggagawa (the union) and Monterey Foods Corporation (the company)

expired. On March 28, 2003 after the negotiation for a new CBA reached a

deadlock, the union filed a notice of strike with the National Conciliation and

Mediation Board (NCMB). To head off the strike, on April 30, 2003 the company

filed with the DOLE a petition for assumption of jurisdiction over the dispute in

view of its dire effects on the meat industry. In an Order dated May 12, 2003, the

DOLE Secretary assumed jurisdiction over the dispute and enjoined the union from

holding any strike. It also directed the union and the company to desist from

taking any action that may aggravate the situation.

On May 21, 2003 the union filed a second notice of strike before the NCMB

on the alleged ground that the company committed unfair labor practices. On June

10, 2003 the company sent notices to the union officers, charging them with

intentional acts of slowdown. Six days later or on June 16 the company sent new

notices to the union officers, informing them of their termination from work for

defying the DOLE Secretarys assumption order.

On June 23, 2003, acting on motion of the company, the DOLE Secretary

included the unions second notice of strike in his earlier assumption order. But,

on the same day, the union filed a third notice of strike based on allegations that

the company had engaged in union busting and illegal dismissal of union

officers. On July 7, 2003 the company filed a petition for certification of the labor

dispute to the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) for compulsory

arbitration but the DOLE Secretary denied the motion. He, however, subsumed the

third notice of strike under the first and second notices.

On November 20, 2003 the DOLE rendered a decision that, among other

things, upheld the companys termination of the 17 union officers. The union and

its officers appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals (CA).

On May 29, 2006 the CA rendered a decision, upholding the validity of the

companys termination of 10 union officers but declaring illegal that of the other

seven. Both parties sought recourse to this Court, the union in G.R. 178409 and

the company in G.R. 178434.

The Issues Presented

The issues these cases present are:

1. Whether or not the CA erred in holding that slowdowns actually

transpired at the companys farms; and

2. Whether or not the CA erred in holding that union officers committed

illegal acts that warranted their dismissal from work.

The Rulings of the Court

First. The law is explicit: no strike shall be declared after the Secretary of

Labor has assumed jurisdiction over a labor dispute. A strike conducted after such

assumption is illegal and any union officer who knowingly participates in the

same may be declared as having lost his employment.

[1]

Here, what is involved is

a slowdown strike. Unlike other forms of strike, the employees involved in a

slowdown do not walk out of their jobs to hurt the company. They need only to

stop work or reduce the rate of their work while generally remaining in their

assigned post.

The Court finds that the union officers and members in this case held a

slowdown strike at the companys farms despite the fact that the DOLE Secretary

had on May 12, 2003 already assumed jurisdiction over their labor dispute. The

evidence sufficiently shows that union officers and members simultaneously

stopped work at the companys Batangas and Cavite farms at 7:00 a.m. on May 26,

2003.

The union of course argues that it merely held assemblies to inform

members of the developments in the CBA negotiation, not protest demonstrations

over it. But as the CA correctly observed, if the meetings had really been for the

stated reason, why did the union officers and members from separate company

farms choose to start and end their meetings at the same time and on the same

day? And if they did not intend a slowdown, why did they not hold their meetings

after work. There is no allegation that the company prevented the union from

holding meetings after working hours.

Second. A distinction exists, however, between the ordinary workers

liability for illegal strike and that of the union officers who participated in it. The

ordinary worker cannot be terminated for merely participating in the

strike. There must be proof that he committed illegal acts during its conduct. On

the other hand, a union officer can be terminated upon mere proof that he

knowingly participated in the illegal strike.

[2]

Still, the participating union officers have to be properly identified.

[3]

The

CA held that the company illegally terminated union officers Ruben Alvarez, John

Asotigue, Alberto Castillo, Nemesio Agtay, Carlito Abacan, Danilo Rolle, and

Juanito Tenorio, there being no substantial evidence that would connect them to

the slowdowns. The CA said that their part in the same could not be established

with certainty.

But, although the witnesses did not say that Asotigue, Alvarez, and Rolle

took part in the work slowdown, these officers gave no credible excuse for being

absent from their respective working areas during the slowdown. Tenorio

allegedly took a break and never went back to work. He claimed that he had to

attend to an emergency but did not elaborate on the nature of such emergency. In

Abacans case, however, he explained that he was not feeling well on May 26,

2003 and so he decided to take a two-hour rest from work. This claim of Abacan

is consistent with the report

[4]

that only one officer (Tenorio) was involved in the

slowdown at the Calamias farm.

At the Quilo farm, the farm supervisor did not include Castillo in the list of

employees who failed to report for work on May 26, 2003.

[5]

In Agtays case, the

evidence is that he was on his rest day. There is no proof that the unions

president, Yolito Fadriquelan, did not show up for work during the

slowdowns. The CA upheld his dismissal, relying solely on a security guards

report that the company submitted as evidence. But, notably, that report actually

referred to a Rolly Fadrequellan, another employee who allegedly took part in the

Lipa farm slowdown. Besides, Yolito Fadriquelan was then assigned at the

General Trias farm in Cavite, not at the Lipa farm. In fact, as shown in the sworn

statements

[6]

of the Cavite farm employees, Fadriquelan even directed them not to

do anything which might aggravate the situation. This clearly shows that his

dismissal was mainly based on his being the union president.

The Court sustains the validity of the termination of the rest of the union

officers. The identity and participations of Arturo Eguna,

[7]

Armando

Malaluan,

[8]

Danilo Alonso,

[9]

Romulo Dimaano,

[10]

Roel Mayuga,

[11]

Wilfredo

Rizaldo,

[12]

Romeo Suico,

[13]

Domingo Escamillas,

[14]

and Domingo Bautro

[15]

in

the slowdowns were properly established. These officers simply refused to work

or they abandoned their work to join union assemblies.

In termination cases, the dismissed employee is not required to prove his

innocence of the charges against him. The burden of proof rests upon the

employer to show that the employees dismissal was for just cause. The

employers failure to do so means that the dismissal was not justified.

[16]

Here, the

company failed to show that all 17 union officers deserved to be dismissed.

Ordinarily, the illegally dismissed employees are entitled to two reliefs:

reinstatement and backwages. Still, the Court has held that the grant of separation

pay, instead of reinstatement, may be proper especially when as in this case such

reinstatement is no longer practical or will be for the best interest of the

parties.

[17]

But they shall likewise be entitled to attorneys fees equivalent to 10%

of the total monetary award for having been compelled to litigate in order to

protect their interests.

[18]

WHEREFORE, the Court MODIFIES the decision of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. SP 82526, DECLARESMonterey Foods Corporations

dismissal of Alberto Castillo, Nemesio Agtay, Carlito Abacan, and Yolito

Fadriquelan illegal, andORDERS payment of their separation pay equivalent to

one month salary for every year of service up to the date of their termination. The

Court also ORDERS the company to pay 10% attorneys fees as well as interest of

6% per annum on the due amounts from the time of their termination and 12% per

annum from the time this decision becomes final and executory until such

monetary awards are paid.

SO ORDERED.

ROBERTO A. ABAD

Associate Justice

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Best in YouDocument33 pagesThe Best in YouEgwim Ifeanyi100% (4)

- Jataka Tales: Stories of Buddhas Previous LivesDocument12 pagesJataka Tales: Stories of Buddhas Previous LivesTindungan DaniNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit RuleDocument6 pagesJudicial Affidavit RulepacalnaNo ratings yet

- Sample of Judicial AffidavitDocument5 pagesSample of Judicial AffidavitpacalnaNo ratings yet

- Strike Cases in LaborDocument51 pagesStrike Cases in LaborpacalnaNo ratings yet

- Micro Econ Topic Tracker 2023Document5 pagesMicro Econ Topic Tracker 2023ryan sharmaNo ratings yet

- 7 Wonders of ANCIENT World!Document10 pages7 Wonders of ANCIENT World!PAK786NOONNo ratings yet

- 5Document31 pages5Alex liao0% (1)

- ISO 10014 2021 Revision Overview - Realizing Financial and Economic BenefitsDocument11 pagesISO 10014 2021 Revision Overview - Realizing Financial and Economic BenefitsalfredorozalenNo ratings yet

- Understanding Bangsamoro IndependenceDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Bangsamoro IndependencepacalnaNo ratings yet

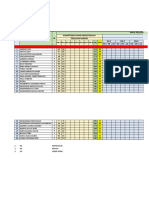

- Master Nilai RDM Semseter Gasal 2020 Kelas 1Document50 pagesMaster Nilai RDM Semseter Gasal 2020 Kelas 1Ahmad Syaihul HNo ratings yet

- Purpose and Process of WHO GuidelineDocument14 pagesPurpose and Process of WHO GuidelineDisshiNo ratings yet

- Assistant Sub Inspector (BS-09) Anti Corruption Establishment Punjab 16 C 2020 PDFDocument3 pagesAssistant Sub Inspector (BS-09) Anti Corruption Establishment Punjab 16 C 2020 PDFAgha Khan DurraniNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of IntrestDocument11 pagesConflicts of IntrestDRx Sonali TareiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Guide 2.2 Beware of Banking FeesDocument4 pagesLesson Guide 2.2 Beware of Banking FeesKent TiclavilcaNo ratings yet

- English PresentationDocument6 pagesEnglish Presentationberatmete26No ratings yet

- Inventory Control Software Business PlanDocument28 pagesInventory Control Software Business Planhemansh royalNo ratings yet

- Art Region 3Document49 pagesArt Region 3JB LicongNo ratings yet

- Resting in The RiverDocument4 pagesResting in The RiverNguyễn Văn TưởngNo ratings yet

- Erectors Inc. v. NLRC 256 SCRA 629 (1996)Document4 pagesErectors Inc. v. NLRC 256 SCRA 629 (1996)Rosel RamsNo ratings yet

- Syllabus-LEC-GOVT-2306-22201 John McKeownDocument18 pagesSyllabus-LEC-GOVT-2306-22201 John McKeownAmy JonesNo ratings yet

- WORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT of The Ultra Light Technology. VidishaDocument49 pagesWORKING CAPITAL MANAGEMENT of The Ultra Light Technology. Vidishasai projectNo ratings yet

- Quo Vadis PhilippinesDocument26 pagesQuo Vadis PhilippineskleomarloNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: Perspectives On The History of Education in Nigeria, 2008Document26 pagesChapter One: Perspectives On The History of Education in Nigeria, 2008Laura ClarkNo ratings yet

- End of The Earth.......Document3 pagesEnd of The Earth.......Plaban Pratim BhuyanNo ratings yet

- Chapter Eleven: Being With Others: Forming Relationships in Young and Middle AdulthoodDocument46 pagesChapter Eleven: Being With Others: Forming Relationships in Young and Middle AdulthoodAnonymous wYPVX3ZIznNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Introduction To Cost Management SystemsDocument6 pagesChapter 12 Introduction To Cost Management SystemsAnne Marieline BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- TranscendentalismDocument3 pagesTranscendentalismapi-306116382No ratings yet

- Unit 2 PDFDocument39 pagesUnit 2 PDFNoorie AlamNo ratings yet

- School Calendar Version 2Document1 pageSchool Calendar Version 2scituatemarinerNo ratings yet

- Claire Churchwell - rhetORICALDocument7 pagesClaire Churchwell - rhetORICALchurchcpNo ratings yet

- Josefa V MeralcoDocument1 pageJosefa V MeralcoAllen Windel BernabeNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 2640Document4 pagesSyllabus 2640api-360768481No ratings yet

- English Silver BookDocument24 pagesEnglish Silver BookQamar Asghar Ara'inNo ratings yet