Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Sojourner PDF

Uploaded by

robertsurcoufOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Sojourner PDF

Uploaded by

robertsurcoufCopyright:

Available Formats

THE SOJOURNER

PAUL C. P. SIU

ABSTRACT

The "sojourner" is treated as a deviant type of the sociological form of the "stranger," one who clings

to the cultural heritage of his own ethnic group and tends to live in isolation, hindering his assimilation

to the society in which he resides, often for many years. The sojourn is conceived by the sojoumer as a

"job" which is to be finished in the shortest possible time. As an alternative to that end he travels back

to his homeland every few years. He is comparable to the "marginal man."

THE "SOJOURNER" DEFINED

About forty years ago Simmel wrote in

his Soziologie an analysis of an ideal type,

with reference to race and culture contacts,

which he called "der Fremde."^ Sociologists

in America and abroad have done much

significant work implicitly and explicitly on

the general subject of the social type that

results from race and culture contacts. Park,

particularly, coined a term which he saw

fit to use in the study of the kind of rela-

tionship between racial hybrids and "the

two worlds in both of which he is more

or less a stranger""the marginal man."^

I am proposing to isolate another deviant

type, for which I employ the term "sojourn-

er." The sojourner, to be sure, is charac-

teristically not a marginal man; he is

different from the marginal man in many

aspects. The essential characteristic of the

sojourner is that he clings to the culture

of his own ethnic group as in contrast to the

bicultural complex of the marginal man.

Psychologically he is unwilling to organize

himself as a permanent resident in the

country of his sojourn. When he does, he

becomes a marginal man.

Both the marginal man and the sojourner

' Georg Simmel, Soziologie (Leipzig: Duncker

& Humblot, 1908), pp. 685-91. Englbh transla-

tions: Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess,

Introduction to the Science of Sociology (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1924), pp. 322^27;

Kurt H. Wolff, The Sociology of Georg Simmel

(Glencoe, III.: Free Press, 1950), pp. 402-8.

'Robert E. Park, "Human Migration and the

Marginal Man," American Journal of Sociology

XXXIII (May, 1928), 881-93.

are types of strangerin Simmel's sense,

products of the cultural frontier.* No

doubt, in many instances, the sojourner has

something in common with the marginal

man. It is convenient, therefore, to define

the "sojourner" as a stranger who spends

many years of his lifetime in a foreign

country without being assimilated by it.

The sojourner is par excellence an ethnocen-

trist.* This is the case of a large number of

immigrants in America and also of Ameri-

cans who live abroad. The Chinese laundry-

man, for example, is a t5^ical sojourner,

and so is the American missionary in China.

The concept may be applied to a whole

range of foreign residents in any country

to the extent that they maintain sojourner

attitudes. The colonist, the foreign trader,

the diplomat, the foreign student, the inter-

national journalist, the foreign missionary,

the research anthropologist abroad, and all

sorts of migrant groups in different areas

of the globe, in various degree, may be con-

sidered sojourners in the sociological sense.

In the new country the sojourner has

indeed gone through a series of adjustments

to his present environment, and he is very

' Everett C. Hughes defines cultural frontiers as

"[where] two or more cultures are in conflict"

(An Outline of the Prindples of Sodology, ed.

Robert E. Park [New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc.,

1939], p. 300).

* WilUam G. Sumner, Folkways (Boston: Ginn

& Co., 1906), pp. 13-15: "Ethnocentrism is the

technical name for this view of things in which

one's own group is the center of everything, and

all others are scaled and rated with reference

to it."

34

THE SOJOURXER 35

likely to be an agent of cultural diffusion

between his homeland and the country of

his sojourn. The sojourner, however, can

hardly be assimilated. The essence of as-

similation, according to Park and Burgess,

is "a process of interpenetration and fusion

in which person and group acquire the

memories, sentiments and attitudes of other

persons or groups, and by sharing their ex-

perience and history, are incorporated with

them in common cultural life."^ It seems

that the sojourner, on the contrary, tends to

be isolated instead.

The characterization of the sojourner

given by Simmel is not that of the man

"who comes today and goes tomorrow but

rather of the man who comes today and

stays tomorrow." The concept, let me re-

peat, is applied only in the general context

of race and culture contacts; it has no

reference to, for example, a New Yorker

who moves to San Francisco.

Social situations relative to this general

problem in different countries in our time

often set people apart, hindering the process

of assimilation or at least making it very

slow. The social adjustments and activities

of the sojourner, to be sure, vary in detail

in particular situations. There are, however,

some general and essential characteristics

which must be ascribed to the sojourner.

THE JOB

Perhaps it is logical to consider first what

it is that makes the sojourner go abroad and

stay on. Apparently he knows why he mi-

grates. It may be a religious mission, a com-

mercial interest, an economic adventure, a

military campaign, an academic degree, a

journalist assignment, a political refuge, or

what not. In spite of the seemingly hetero-

geneous motives and aims, there is, how-

ever, something common to all of them;

the intrinsic purpose of the sojourn is to

do a job and do it in the shortest possible

time. The sojourner seldom organizes his

Park and Burgess, op. dt., p. 735.

Simmel (see Park and Burgess, "The Sociolog-

ical Significance of the 'Stranger,'" op. dt., p.

3").

life beyond the accomplishing of this end.

The term "job" used here is to indicate a

deviation from the term "career." Career

is to be conceived as lifelong work, but the

job can be only a part of one's career. It

is quite clear in some of the cases. A for-

eign student, for instance, may stay several

years in order to get his degree, but his

school work is only the beginning of his

career. A research anthropologist nmy visit

and revisit a primitive society, but it is

clear that his project may not be his life-

long career. A religious mission, on the

other hand, is relatively harder to identify

as a job or a career because missionary

workers tend to stay abroad longersome

until retirement, others several years^and

each has a particular reason or reasons for

the decision to stay or to leave. The hope

and dream of an economic adventurer is,

of course, to make a fortune, and the length

of the sojourn depends uf)on his success or

failure in the adventure. His job, like that

of the missionary, may be finished in sev-

eral years or may be prolonged for decades.

Generally speaking, it seems that the time

element varies according to individual situ-

ations, but the job itself is essentially a

means to an end. The sojourner may not

necessarily like his job and enjoy working

at it. It is rather that he is fighting for

social status at home. The job, therefore,

is tied up with all sorts of personal needs

for new experience, security, prestige, etc.

Although the sojourner plans to get

through with the job in the shortest pos-

sible time, yet he soon finds himself in a

dilemma as to whether to stay abroad or to

return home. Naturally this problem is re-

lated to the success or failure of the job

he would not like to return home without

a sense of accomplishment and some sort of

security. But this state is psychologically

never achieved. In due time tiie sojourner

becomes vague and uncertain about the ter-

mination of his sojourn because of the fact

that he has already made some adjustments

to his new environment and acquired an

old-timer's attitudes. "You promised me

to go abroad for only three years," com-

36

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY

plained the wife of a Chinese laundry man

in a letter to him, "but you have stayed

there nearly thirty years nowl"^

This feature of staying on indefinitely

is indeed interesting. In his effort to make

his job a success, the sojourner stays on

long enough to make changes in his life-

organization, so that he is no longer the

same person; in other words, he has de-

veloped a mode of living peculiar to his

present situation. He has no desire for full

participation in the community life of his

adopted land In other words his activities

tend to be within the l.nut of h.s own mter-

es t - t he job. He tends to think of himself

as an outsider and feels content as a spec-

tator in many of the community affairs.

If he does take part in certain activities,

they are likely to be either matters reUting

to his job or matters concerning his home-

land's social welfare, politics, etc. Essen-

tially his activities in the community are

symbiotic rather than social. The public

seldom thinks of him other than in relation

to his job. He therefore is an individual

who performs a function rather than a per-

son with a social status. He is a person only

to the people of his own ethnic group or to a

social circle related to his job.

Related to the symbiotic level of the so-

journer's activities is another feature which

is what may be called the "alien" element

of the job. Whatever it is, it is something

foreign to the natives. It is either something

transplanted by the sojourner from his

homeland or something new invented by

him in his struggle for existence abroad.

In America the Chinese laundry,^ the Ital-

ian fruit stand, the Greek ice-cream parlor,

and the Jewish clothing store are inventions

by which these immigrant groups survive

in the highly competitive urban commu-

nity. So, too, the Christian church, the hos-

pital, the oil refinery, the modern school

and the archeological excavation are indeed

' A personal letter in Chinese collected by Paul

C. p. Siu in 1943.

Paul C. P. Siu, "The Chinese Laundryman: A

Study of Sodal Isolation" (unpublished mono-

h)

new elements which may disturb the social

order of the folk society into which they

are introduced.

Because of the alien element in the job,

at least for the time being, the sojoumer

is not considered as a competitor of the

natives. Paradoxically he often finds him-

self a keen competitor of the people of his

own ethnic group.

IN-GROUP TENDENCY

^^ ^ ^ ^.^ cLVrymen, if there are enough

' ^ , j ^ J ^^^^ ..^itt,, Tokyo,"

J ^^ ^ ^ .^own," and "China-

^ ^J^ ^ for example, are

">"' f f = : ^n mteresting journalistic

account of 3,600 Americans in Saudi Araba

shows that the colony is completely on

American standards; the Arab world sur-

rounding it is spoken as a Land of Wajid

Mafe"meaning "the land of plenty of

^he formation of the cultural colony re-

synjbiotic segregation, on the one

' Whether the sojourner lives wiA or

? ]? socialhfe ties up with

activities in the racial colony

. ^ tendency for forming m-grip

relationships. The desire to live together

1 ^ ^ ?

- The colony in its process of

development does not always grow m one

segregation may take the

scattering around an area and

maintaining only a center or several centers

activities. The center of activities

developed into a segre-

^ number of the same

ethnic group can maintain themselves local-

ly. The crucial factor, therefore, is the in-

dustrial and social potentiality of the me-

"Arabian Oil: American Enterprise in the

Desert," Life, March 28, 1949.

THE SOJOURNER 37

tropolis. Chinatown in Chicago, for in- tain one another at their homes. They share

stance, originated in 1872 in a lone laun- their pride and aspirations, hof>es and

dry shop located between Clark and Madi- dreams, prejudices, and dilemmas and ex-

son streets. Several decades later it grew press their opinions about the country of

to be the third largest Chinese colony in this their sojourn. The following narrative tells

country, with scores of stores and hundreds vividly what may be called a sojourner's

of laundry shops and chop suey houses scat- attitude.

tered all about the metropoUtan area.^^ It ^^ ^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^ ^^^ Americans was a

grew because Chicago itself developed from ^^^ ^^^ ^ ^ ^^^^^ ^^em a little; they had

a frontier fort into the second largest city ^ country they could call their own. It was,

in the country. morever, a fairly nice country; not like Russia,

In the smaller cities where we found one but, in the long run, not a bad one. It could

or more chop suey restaurants and scores of have been a very good country if Russians had

Chinese laundry shops, we found also, at settled it a few centuries ago; now it was too

the periphery of the central business dis- l^^e; the Americans had to content themselves

trict, one or more Chinese stores which are ^^^ ^.^^ ^^^^ ^ ^ ' . , .

the centers of activity for the local Chinese ^""^.^ "' ^ " " ' ^ ^ ^'""'^ ^^^ ^^' ^^

I ,. rr . ., 4. * association with the natives we are compelled

population. To be sure the store may not ^^ ^ ^^ ^^^^ ^ ^ ^^^^ difficuhand

have origmated as such an enterprise. It unpleasant tongue, hard and harsh, forbidding

could be a former laundry shop converted and unyielding, lacking the softness and elas-

into a store as the local Chinese population ticity of our own Russian language. As soon as

increased, which, because of its position our working day was over and we had shed our

became a shopping center where homeland overalls, we became Russians. We went to our

merchandise is offered. Occasionally local Russian affairs; we assembled in Russian homes

people of the ethnic group congregate there around Russian saniovars; ate Russian food,

for social affairs and recreation. This is the ^"^^"^ ^^^sian tea (the tea was, unfortunately,

situation, for instance, in Richmond, Vir- "If 1^ ? ^ew York) and discussed Russian

ginia, and Indianapolis, Indiana. In sUU affairs in Russian language.

11 '4.- I'l -n 4.4.1 r^ 1 -Kit' I . ' One of our mam topics was this country,

smaller cities like Battle Creek, Michigan, ^^^ we most definitely did not like it. This

and Portland, Mame, there is no Chinese country was definitely inferior to Russia-^ven

store, but the local Chinese usually congre- to Russia when we left there."

gate in the rear of a downtown laundry

shop where facilities for recreation and per- Although this is a Russian story, yet it

sonal contacts are available. The local colo- describes the general reaction of all ininii-

ny has not grown, because the local popu- ^^^^ groups which happen to be minorities

lation of the ethnic group has remained too '^"^ ^ foreign country. This sort of attitude

small. seems to prevail in the mind of the so-

Essentially the colony is an instrument Journer and that is why he has to seek his

to establish or to re-establish some sort of countrynien as neighbors and friends. Home

primary-group relationships in the matrix ^^^ family life, perhaps, show most inter-

of homeland culturean effort to create a estingly how the sojourner can maintain his

home away from home. Whatever activities homeland cultural heritage abroad. Food

the sojourner may participate in, in the com- habits seem to be the most persistent. The

munity at large, in private life he tends to Chinese invented chop suey to suit the

live apart from the natives and to share Americans' appetite while he enjoyed typi-

with his countrymen in striving to main- ^al home dishes such as chia-chang-yu-pien

tain homeland culture. His best friends are (steamed pork with imported shrimp sauce)

people of his ethnic group, and they enter- which most Americans dislike. Homeland

* Siu, 0^ eft., chap, ii: "The Growth and Dis- "Mikhail Jeleznov, "Part-Time Americans,"

tribution of the Chinese Laundry in Chicago." Common Ground, Vol. X, No. 1 (autumn, 1949).

38 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY

tongues, art, sentiments, and primary-group

attitudes fortify the sojourner in his effort

to maintain homeland culturealthough

there are variations among different ethnic

groups within one country and in different

countries. The American missionary, for

instance, can keep his homeland culture

intact better than most of the immigrant

groups in America. He is more successful

in isolating his children from the native

inffuences, sending them to an American

school and living in a segregated area. Pearl

Buck illustrated this point very well.

The American home I know very well, part-

ly from close observation of homes during the

years that I have been living in my own coun-

try but as much from my own typically Amer-

ican home in China. My parents were Amer-

ican, patriotic to the core, and simply and hon-

estly convinced, as most Americans are, that

the American home is the best in the world.

To them American home life was even a part

of the Christian religion which they felt it

their duty and privilege to preach to the

Chinese. I do not believe it ever occurred to

my parents in the goodness of their saintly

hearts to ask themselves whether or not the

Chinese had a sort of home life which was per-

haps as valuable in its way as ours, or at least

better suited to China than ours was.

Our home, therefore, was kept absolutely and

carefully American. We had American furni-

ture and American food, though all of us chil-

dren liked Chinese food better, and only as a

concession to our pleading did we have an

occasional Chinese meal. Beyond that we satis-

fied our craving by partaking heartily of the

servants' meals before our own and listening

in guilty silence to our mother worrying over

our small appetites. We got up in the morn-

ing and had prayers and ate porridge and eggs

for breakfast, and studied our American les-

sons, and on Sunday a Christian church bell

rang and we went to church, and the only

difference was that the Christians in that

church were Chinese instead of American. We

were trained in all the ways of American home-

making, and spiritually we were kept close not

to the Chinese about us but to our own loved

land thousands of miles away that we had

never known except through our parents' eyes

and words.*2

"Pearl Buck, Of Men and Women (New York:

John Day, 1941), pp. 33-34.

But the Chinese immigrant in the United

States cannot isolate his children so suc-

cessfully as the American missionary io

China can. The Chinese immigrant has to

send his children to American schools. The

Chinese child, therefore, is more likely to

become a marginal man. The following

story illustrates the intrinsic characteristic

of the cultural pattern and the problem it

creates.

The relationship between father and chil-

dren in our family, as in most Chinese fami-

lies, is of a very formal nature. I never think

of cracking jokes with daddy. . . .

Respect we children always observefor in-

stance, by carefully calling an older sister "sec-

ond older sister" and never the familiar "Jade

Lotus" which only those older than she can

use. The practical result of the system is that

the youngest in the family has no one with

whom he can be familiar. Nothing is so effec-

tive in keeping this present adolescent quiet

as to remind him that he is the smallest; there-

fore he can say nothing imprudent to anyone

else; nor can he safely call anything his own.

It can be seen that there is little room for

individuality in a Chinese family such as ours.

We are early instructed that we must never

bring disgrace to the family name, and that

individual achievement is less significant than

the resulting family glory. The individual

claims his significance largely from the family

to which he belongs. For instance, in China-

town, introductions usually are no sooner under

way than one is asked (if one is young), "Who

is your honorable father?" The Chinese at-

tempt to submerge individuality leads to tre-

mendous family conflict here in the United

States. My adolescent years were spent in try-

ing to adjust a newly learned American cultural

pattern to a rigid established Chinese standard.

It is revolutionary to hear one's college pro-

fessor say, "Parents should understand their

children instead of demanding just obedience."

Disaster results when adolescents return home

and try to educate parents to this new idea. I

have never tried to do exactly this with my

father, for I am sure that he will never under-

stand his children, though the goal of his whole

life's work has unquestionably been their wel-

fare.

The happiest adjustment in this conflict

between individual expression versus parental

control I have found to lie in expression out-

THE SOJOURNER 39

side of the family circle, acquiescence within.

Such adjustment has not been made without

pain and tears, for other children of the family

as well as myself. In all fairness to daddy, I

must say that if he demands respect, it is not

because he is in any way egotistical, but be-

cause lack of respect for parents results in

confusion of proper relationship. . . .

I have never been in China. My Chinese

heritage, which I hold so dear, has been trans-

mitted to me almost solely by my father in

the cultural pattern which he has stamped up-

on me; singularly, how he imposed it does not

seem to matter any

Both of the foregoing cases show parents

who obviously have sojourners' attitudes,

trying to maintain their homeland cultural

heritage; the child in the former case, how-

ever, does not suffer from cultural conflict,

while the child in the latter case does. These

differences, it seems, are due to the differ-

ent situations in China and in America.

What makes the differences in detail in race

and culture relation in these two countries

is indeed very interesting. It is not, how-

ever, the purpose of this paper to under-

take such an analysis. My attempt so far

has been to show how the sojourner behaves

as an individual, with reference to his job,

then to describe his activities as a person

among people of his own ethnic group, and,

finally, in the following section, I will at-

tempt to show his relation to the country

of his sojourn and his homeland. Indeed,

he is not t)^ically a sojourner unless he has

maintained his homeland tie.

MOVEMENT BACK AND FORTH

The sojourner stays on abroad, but he

also never loses his homeland tie. In the

beginning he ventured to take up residence

in a foreign country with a definite aim.

Soon he found that the job was taking much

longer than he had expected. His original

plan, as a matter of fact, has been compli-

cated by new social values and social atti-

tudes. As a means to an end, a new orien-

tation has been adopted; he stays several

years, and, when opportunity permits, he

"Jade Snow Wong, "Daddy," Common

Ground, Vol. V, No. 2 (winter, 1945).

takes a trip home for a visit. The trip is an

accomplishment, but the job can never be

finished. Again he has to go abroad. In his

lifetime several trips are made back and

forth, and in some cases the career is termi-

nated only by retirement or death.

In the preceding section, we have stated

that the sojourner wants the job done in the

shortest possible time. Obviously, achieve-

ment of this objective depends largely upon

his ability, on the one hand, and his chance

or luck, on the other hand. Each individual

is not exactly like another, and yet we have

a whole range of cases in which differences

can be described and compared in terms of

the type of job, homeland background, race

and cultural situation abroad, and personal

adjustments in response to these circum-

stances.

Typical examples of the movement back

and forth are the missionary's furlough and

the immigrant's trip home. This movement

is characterized by ethnocentrism in the

form of social isolation abroad and social

expectation and status at home. In other

words, one has gained some sort of recog-

nition of his accomplishment by his friends

and relatives both at home and abroad.

While staying abroad, the sojourner keeps

his home tie by writing letters, exchanging

gifts, and participating in home social and

political affairs. In contrast to his role on

his job, these activities seem to be purely

on the basis of convention, and there is

nothing to indicate the element of expedi-

ency, as in the activities of his job. The

return trip is the result of a social expec-

tation of members of his primary group as

much as of his individual effort; their senti-

ments and attitudes make his trip meaning-

ful. The trip shows that he is a person to be

admired, to be appreciated, to be proud of,

and to be envied.

To illustrate the movement back and

forth, the following case selected from the

Chinese group is especially significant be-

cause it seems to be nearly a perfect cycle

of the sojourner's career, with the usual

sequence of trips taken every few years.

Moreover, the pattern of behavior is carried

from father to son. It seems to represent

40

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY

a life-cycle comparable to that of the mar-

ginal man.

Mr. C. came to America in 1919 at the age

of 19, two years after his marriage in his

native village in China. Soon after his arrival

he began to work with his father and two cous-

ins in a laundry shop uptown. Their laundry

shop was established about twenty-five years

ago by his father and two partners. It had been

very prosperous and was in need of helpers

badly. A young man working with them was

a great help. "The work was hard," said Mr.

C, as he recalled his experience in the bygone

days, "I almost wanted to give up. But what

else could I do? After all, the old men were

working just as hard as I was. What could we

Chinese do in this country? You don't know

even how to speak their language [Eng-

lish]. . . . "

The newcomer was encouraged to attend the

Sunday school conducted by one of the church-

es in town, for some of his young clansmen

were also pupils there and they went together.

The church maintained Sunday school classes

every Sunday afternoon especially for the

Chinese, teaching them English and Bible les-

sons. For the first time Mr. C, a country boy

from China, met his Sunday school teacher,

Mrs. J., a housewife. He attended the class

steadily for several years. Gradually he could

speak English to his customers but was not

converted. He admitted that his English was

not adequate and he was not able to read

newspapers (English papers). "Who ever

thought of staying in this country so long?"

Mr. C. recalled that he expected to retum to

China in a few years and stay home for good.

And that was why he had no incentive to

leam more English. In fact he had no time to

study at that time, as the business was very

good and they had to work day and night

except Sunday.

Besides his acquaintance with the church

people and his impersonal business contacts

with his customers in the laundry shop, Mr.

C.'s social activities were largely among his

clansmen and his fellow-countrymen in China-

town. He became an active member in C.

clan. Later he joined the Kuomintang (Chinese

Nationalist party), became active in the Chung

Wah Association (usually known to Americans

as the Benevolent Association), and was in-

terested in social welfare in his native village

as well as in China. He liked to have his name

in the Chinese newspapers every now and then.

In 1925 the laundry shop was sold, and the

father and son went back to China. The old

man thought it was time for him to retire, and

it was his fourth trip back home. But Mr. C.

could have stayed here longer. Why had be

to leave too? He said he was afraid something

might happen to his father on the way; the old

man was too old and was taking a large sum of

money with him. Of course his wife wrote and

urged him to come home too, for they had no

children as yet. The real reason, which Mr. C.

did not tell explicitly, was that he and his

father thought that they had enough money to

live in style in China even if Mr. C. decided

not to retum to America again. The family

was known in their native district as being

well-to-do even before Mr. C. came to Ameri-

ca to join his father in 1919. His father was a

good provider and "home builder" in all the

years. They had lands and business invest-

ments and a good semi-Westem-style house in

the native village. At this time, they took home

with them about forty thousand dollars.

In the year after the father and son reached

home, the C. family married away Mr. C.'s

younger sister. It become known in the whole

district; people said that the dowry for the

young bride consisted of 25 American gold dol-

lars and a full possession of teakwood furni-

ture, dozens of dresses, and, what was more,

a slave maid.

Later, Mr. C. invested a large sum of money

in a textile enterprise in the city of Canton.

Unfortunately it turned out to be a complete

failure, for which Mr. C. blamed the dis-

honesty of cousins and the incompetency of

the management.

The spending was excessive and the loss was

unexpected. Mr. C. had to come to America

again and again worked in another laundiy

shop with one of his relatives, and the business

was very good. In a few years he was able to

save enough to make another trip. In 1929 his

family urged him to retum. At this time his

father had died and his mother wanted to see

him before her passing away.

Mr. C. was soon in China but he did not

plan to stay for good this time. He came again

after a year of staying with his fantiily. Com-

plaining that it is "too easy to spend all money

in China," he said he gave his mother a birth-

day banquet, inviting the whole village. He

also helped the village to re-establish the vil-

lage school; the old school was disorganized.

THE SOJOURNER

He would have to send his son to school soon.

"He was too young yet," Mr. C. said, "but I

could not let my son grow up without a school

to attend. So for the good of the village as well

as niine there had to be a school for the chil-

dren. I spent over a thousand dollars for it, but

if I did not take the lead, no one seemed to

care to do it."

"And when I arrived in this country again,"

Mr. C. continued, "it was 1930 and it was the

coming of the great depression. Life was hard

here too but not as bad as in China. The peo-

ple had been so poor that it sickened my heart.

When I was in China, friends and relatives all

came for money, one way or the other. It was

hard to deal with them without hurting their

feelings. They did not believe that I had spent

almost all my money. After all, I had to keep

some to support my family and for my trip

back here."

"This is a wonderful country," said Mr. C,

in response to a question about his feeling to-

ward America. "Everything is orderly accord-

ing to the law. Look at their industryI don't

know when China can follow it up. After all,

we Chinese are just staying here temporarily.

We are just outsiders. Outsiders, particularly

of the nonwhite race, have not much of a

chance. Some Americans are very nice to you,

but deep in their hearts you are still, they

know, different from their own. So we should

hope that China would be prosperous and

strong some day and we can go home and do

something else instead of working as slaves in

the laundry shop and chop suey house."

From 1930 to 1940 Mr. C. had been in

partnership with someone in two chop suey

restaurant businesses. At the beginning, Mr. C.

worked as a cook for two or three years; later

he became a waiter. The business was very

poor because of the depression. Both of the

restaurants in which he was in partnership

failed and, finally, he was employed as a waiter

in one of the best chop suey restaurants in

Chinatown.

It was about 1940 and Mr. C. was thinking

of taking another trip home or of arranging for

his son to come to this country. It was a hard

decision to make at the time, for he had not

much money. Alas I World War II broke out

and it blocked Mr. C.'s plan. Worse still, he

lost contact with his family after the Japanese

took Hong Kong and Canton. When the war

was over, in 1946, Mr. C. leamed that his

mother was dead and his wife very sick, and

that his son was under the care of relatives.

His relatives wrote and urged him to retum

for a reunion.

Mr. C. was with his family again as soon as

he could arrange his trip. Soon after he was

home, his wife died. Then he took his son to

Hong Kong, where the youth was sent to a

missionary school. At this time, he married a

woman twenty years younger than he. He said

he bought a house for his young bride and

stayed with her only four months. Then he

had to leave for America again.

After Mr. C. reached here, he retumed to

his old job in the restaurant. A few months

later, he heard that his second wife had given

birth to a baby girl. At the present time

(1948), Mr. C. is very much interested in get-

ting his son over to this country. He was told

that he could apply for American citizenship

so that he could get his wife into this country

nonquota. His son, however, cannot come non-

quota, for when the youth was bom his father

was not naturalized^nor is he naturalized yet.

It seems that Mr. C. cares mostly to have his

son in this country; like most of his country-

men, his wife's coming has not been in his

mind. He is not going to apply for citizenship

now. At least he has not made up his mind."

We have in this case a representation of

the stages of adjustment: first, Mr. C. has

learned to be an individual who must do

his "job" while, socially, he joins his coun-

trymen in isolation in tiie racial colony and

plans to return to the old country when it is

possible; second, he soon finds himself in

an anomalous position with reference to his

homeland and the country of his sojourn;

third, he projects a hope that someday he

may accomplish his aim, but meanwhile he

goes home for a visit, and the cycle closes

when he makes his final trip home and re-

tires. Comparable with the case of Mr. C.

is that of an American couple who went to

China soon after their marriage, took fur-

loughs every few years, lived in a segre-

gated compound among fellow-missionaries,

sent their children back to America for edu-

cation, and then, finally, came back them-

selves for retirement after fifty years. They

follow the same general patternaccommo-

dation, isolation, and unasslmilation.

"Private document.

42 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY

The problem here is to inquire into the homeor perhaps only one trip^and there

situation that makes the sojourner stay on is no hope for the final one. As they are

abroad. Again each individual case varies now old, poor, and sick, they become in-

in detail according to the situation. After different. Sometimes when a man is asked

a period of residence abroad, one is likely how long he has been in this country, his

to be confronted with personal problems answer reffects self-scorn: "Only five or six

both directly and indirectly affecting his weeksis that enough?" In reality a week

plan. In attempting to solve some of the means seven years. If he says he has been

problems, he sooner or later finds himself here "five weeks," it means thirty-five

in the midst of constant emotional conflicts, years. When asked whether he has been

As time goes on, he becomes, unconsciously back to China for a visit, he may mix good

perhaps, more of a sharer in the racial colo- humor with pity in replying: "I have in-

ny, developing a mode of living which is deed sent letters home several times but

totally characteristic neither of his home have never sent my person!"

nor of the dominant group. That is why The second category of the nondeparture

so many sojourners do not take the trip, cases^which constitute only a small por-

particularly among the migrant groups. A tion of the Chineseare those who have

study of the large congregation of aged their wives and children with them in this

persons in Chinatown reveals an interesting country. The return trip in such cases in-

angle of the situation which deserves a care- volves the attitudes of different members

ful analysis in detail in another paper. From of the family; particularly, there are the

a sample of individual cases we find, first, problems of the second generation. Other

men who could never save enough money factors, such as economic difficulties, busi-

to take the trip. The main reason is largely ness commitments, political unrest, etc.,

due to personal disorganization as a result may prevent departure. However, the mere

of gambling, prostitution, or drug addiction, fact that one has never made his return

Others had large sums of money once or trip is by no means proof that he is not a

twice in their lives but were forced to sojourner. He is, in fact, very much the

stay on because of immigration difficulties, same as his countrymen who do make the

These are the men who reside in America trips. Although he must forego the satis-

lllegally, and, even if they had money faction of a homeland reunion such as his

enough to take a trip home, they would not more fortunate countrymen and friends

do so unless their economic security could have enjoyed, yet the return to the radal

be assured. One of the ways to play safe colony for retirement is to some degree a

would be to secure a return permit from substitute for a home away from home.

'Yr ^r f T ^"'^"y ^o the oW, poor, and sick seek refuge in the

been no immigration provision to adjust the ^ ^ ^ ^l "'^J ' ^'"^ ^^ '' ^^'

status of most of the illegal entry cases , "Jf^^, interracial marriages return

until recently.i These, together with other ^^^"^"^"y ^^ ^^e racial colony. The same

personal problems, often cause the sojourn- ^^^"^^*"' "^ doubtalthough in different

er to stay on for twenty, thirty, forty, or *^g''^c^^is developed among other ethnic

more years without taking a single trip back g''"Ps: "The world at large was cold and

Since the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts f^''^^ ^'' '"^'^ "^^ l\ ^^^^ ^^'^^^^'^

(December 17, 1943), Chinese who could prove ^" abstract and rational intercourse. But

their residence in this country prior to July 4, within the Ghetto he felt free. His contacts

tk^'''f^i *M"? ^r"' A''*'"* ""^"^ S**^'^^'^ ^^th fellow-Jew were warm, spontaneous,

328(b) of the Nationality Act of 1940. More re- and intimate "i

cently, some of them have also been able to adjust ^""matC-

their status under Section 19(0) of the Immigra- "Louis Wirth, The Ghetto (Chicago: University

tion Act of 1917, as amended. of Chicago Press, 1928), p. 26.

THE SOJOURNER 43

Another situation connected with this quite gotten over the freedom of coming

problem of homeland tie is the phenome- and going.^^

non of mass migration due to war and po- Being a potential wanderer, the sojourner

litical persecution, which often resulted in is a skeptic on the subject of homeowner-

such disturbed conditions at home that re- ship. If he does own real estate, he tends

turn became impossible. Under such cir- to think of it as a business proposition, and

cumstances people perhaps arrive at a new he does not suffer a sense of loss when he

orientation and adjustment. The political sells it. His furniture tends to be either

refugees, the White Russians, the German such as he can dispose of without too much

Jews, and the so-called "displaced persons," sacrifice or things he has treasured and

for instance, moved into a developed coun- would like to keep wherever and whenever

try and became its minorities. In a report he moves. If he secures any valuables, they

on recent immigration from Europe to the are likely to be portable objects.

United States, Professor Davie states that

among the i,6oo recent political refugees, METHODOLOGICAL NOTE

96.5 per cent replied that they would re- The concept of "sojourner" developed

main in this country and only 3.5 per cent from my unsuccessful effort, about ten years

of them indicated that they would return ago, to analyze materials gathered when

to their respective countries when the situ- employing the concept "marginal man."i

ation permitted them to do so." It is sig- None of the Chinese laundrymen I studied

nificant to note, however, that in this small could be considered as a marginal man.

proportion there are many professional Consequently it became necessary to look

people and also people from countries where at the subject matter differently. After a

the political system has not been so radical- few years of pondering over both Chinese

ly uprooted. and non-Chinese materials, I was convinced

This is the place to raise the question that he should be treated as a deviant type

whether the state of Israel is the work of from the concept of the stranger which

the sojourner. Here is perhaps a unique Simmel described with such peculiar insight,

example of the fact that a people can main- I was also inspired by Stonequist, who

tain a cultural heritage in the ghetto and stated that "some of the members of the

return to the place where it originated two subordinate or minority group are able to

thousand years afterward without feeling ^^^^ ^^^^^^ ^^^^^ ow" culture, or at least

strange. The Jews have been sojourners for ^ ^^^ ^^ ^^^^ sufficiently not to be greatly

centuries. The sodal solidarity of the ghetto ^^^^urbed by the culture of the dominant

as well as international political change, g^o"P-'"'. The term "sojourner," however,

perhaps, made the movement possible. T^' rr V^T^t PV ""^ T T "t"^'

M^rn^ T>i u * V r *"g Glick's "The Chinese Migrant in Ha-

Marco Polo, whose traveling was famous ^^j j , " since he used the terms "sojourner's

both at home and abroad, returned finally attitudes" and "settler's attitudes.''^^

to Italy after niany years in the court of The sojourner seems to be primarily a

Lathay as a sojourner. The sojourner may social type of the urban community. In the

make several trips back and forth, he may folk society the sojourner probably tends

make only one trip, or he may not make to be more isolated in private life but more

any trip at all. Nevertheless, those who do

not make the trip may remain unassimi-

lated just as much as those who do make it. ^ ^J f , ^ , , , , ,

Psir/^v./^U/*;^.ii !, 4 * 1 Everett V. Stonequist, "The Problem of the

Psychologically the sojourner is a potentiai Marginal Man," American Journal of Sociology,

wanderer, as Simmel puts it, who has not XLI (1935), x-n.

"Clarence E. GUck, "The Chinese Migrant in

Maurice R. Davie, Refugees in America (New Hawaii" (Ph.D. thesis. University of Chicago,

York: Harper & Bros., 1947), pp. 69-76. 1938).

44 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY

active and more influential. The more it is At the present time our knowledge of

a folk group, however, the more difficult it social types resulting from race and culture

is for the sojourner to live in it. One of the contacts is only fragmentary, and there are

most interesting projects on this general large areas unexplored. To achieve a sys-

problem would be a study of the activities tematic knowledge of the type, one of the

of the sojourner in the folk society in com- best ways is through comparative studies

parison with his behavior in the urban com- of the types of situation. Race and ethnic

munity. Studies of different minority groups differences and conflicts are types of sodal

within a given society in comparison with bond related to the growth of personality

a particular minority group in different and institutions.

countries would be promising. Comparative Probably another angle of this problem

studies of this sort would put the research Js another type which has arisen in times of

sociologists in a strategic position to sys- mass migration, when people have moved

tematize their knowledge of the social types into new territories as a result of military

that results from race and culture contacts invasion and colonial expansion. There the

and confficts. newcomers become the dominant group, po-

Sociologists generally agree that the first- utically if not culturally. The building of

generation immigrants, occidental as well empires and mass emigration seem to cre-

as oriental, would not be completely assimi- ate another type of strangerthe settler.

lated anyway. It is, therefore, a question jjg nioves to a country where there is, more

of the degree of assimilation or isolation QJ. jgss, a frontier and where the natives

among a whole range of individual cases have had their own culture but not any-

which, although different from one another ^jjing that we may call civilization. At the

in detail, yet are similar to one another in beginning the social process seems to he

general characteristics. Eventually, we have predominantly the phenomena of conflict

to consider the borderline cases which are and accommodation. Between the new-

neither typically sojourner nor typically comers and the natives and among groups

marginal nian. It will be necessary to study of newcomers, the intergroup relation would

the similarities and differences between the eventually bring some sort of unity through

two types, using the concepts as extreme a long process of acculturation. Those who

poles, and to classify them categorically ^^^^ the pioneers were the settiers. The

and inquire into the situation in which the ^^^^^^^ ^as no problem of assimilation. It

variation derived. seems that in terms of conflict and accom-

It seems that, m dealing with the prob- , ,. ., .., u J c J

1 * 1 * ^ u X 1 1 ~^, ^. modation the settler may be defined m a

lem of social type, the typological technique i i rm. *u

should be more profitable L d promising ^^S'^} .="^- The sojourner on the

than any other method. As Burgess states: * ^ ' ^"^'^ ' "="*"y * product of mass

migration but rather a member of a mi-

The method of typology has proved partic- nority group whose cultural heritage is sub-

ularly appropriate for the collection, classifi- jected to either sodal isolation or assimi-

cation, and analysis of cases. It is, in fact, a Jation

large part of the case-study method so far as

it consists in grouping cases under a given class BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

or classes and then developing a new class for Ernest W. Burgess, "Sociological Research

any negative case, i.e., one that does not fall Methods," American Journal of Sodohgy, L

under any previously postulated class.22 (May, 1945), 478.

You might also like

- In Company of ManDocument568 pagesIn Company of ManantonadiaborgesNo ratings yet

- Between Foreign and Family: Return Migration and Identity Construction among Korean Americans and Korean ChineseFrom EverandBetween Foreign and Family: Return Migration and Identity Construction among Korean Americans and Korean ChineseNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - The Proximity ChallengeDocument7 pagesWeek 5 - The Proximity ChallengeclarissacarvalhoNo ratings yet

- The Englishman in China During the Victorian Era, Vol. I (of 2) As Illustrated in the Career of Sir Rutherford Alcock, K.C.B., D.C.L., Many Years Consul and Minister in China and JapanFrom EverandThe Englishman in China During the Victorian Era, Vol. I (of 2) As Illustrated in the Career of Sir Rutherford Alcock, K.C.B., D.C.L., Many Years Consul and Minister in China and JapanNo ratings yet

- Rudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban AmericaFrom EverandRudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban AmericaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- A Journey of Faith: Moving from the Middle East to the West: Living in Two Different CulturesFrom EverandA Journey of Faith: Moving from the Middle East to the West: Living in Two Different CulturesNo ratings yet

- Transformations of the Liminal Self: Configurations of Home and Identity for Muslim Characters in British Postcolonial FictionFrom EverandTransformations of the Liminal Self: Configurations of Home and Identity for Muslim Characters in British Postcolonial FictionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Knowledge and Power in Morocco: The Education of a Twentieth-Century NotableFrom EverandKnowledge and Power in Morocco: The Education of a Twentieth-Century NotableRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Lesson 3 Elements of Cultural Systems PlanDocument4 pagesLesson 3 Elements of Cultural Systems PlanDiana TabuicaNo ratings yet

- Culture Shock - Negotiating Feelings in The FieldDocument11 pagesCulture Shock - Negotiating Feelings in The FieldDimasluzluzNo ratings yet

- "Swimming Lessons" (1987) : Rohinton MistryDocument25 pages"Swimming Lessons" (1987) : Rohinton MistrySam CruzeNo ratings yet

- Under the Kapok Tree: Identity and Difference in Beng ThoughtFrom EverandUnder the Kapok Tree: Identity and Difference in Beng ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Listening For A ChangeDocument35 pagesListening For A ChangeAngélica FierroNo ratings yet

- Transnational LiteratureDocument14 pagesTransnational LiteratureKelly ChanNo ratings yet

- Twentieth Century Negro Literature Or, A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American NegroFrom EverandTwentieth Century Negro Literature Or, A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American NegroNo ratings yet

- Gilberto Velho. Um Antropólogo Na Cidade: Ensaios De: Antropologia UrbanaDocument4 pagesGilberto Velho. Um Antropólogo Na Cidade: Ensaios De: Antropologia UrbanaJunior SeveroNo ratings yet

- Dominican Republic Culture EssayDocument6 pagesDominican Republic Culture Essayd3gkt7pdNo ratings yet

- Essay Hybrid IdentitiesDocument12 pagesEssay Hybrid IdentitiesMarije Scheffer-van EckNo ratings yet

- The Hindoos as they Are A Description of the Manners, Customs and the Inner Life of Hindoo Society in BengalFrom EverandThe Hindoos as they Are A Description of the Manners, Customs and the Inner Life of Hindoo Society in BengalNo ratings yet

- Towards A Theology of Limnality A LocalDocument33 pagesTowards A Theology of Limnality A LocalS HNo ratings yet

- Text and ContextDocument25 pagesText and ContextIsabel Grace VictorNo ratings yet

- Departure and Return: One Family, Two Countries, and a World of ConnectionsFrom EverandDeparture and Return: One Family, Two Countries, and a World of ConnectionsNo ratings yet

- Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American FrontiersFrom EverandPersonal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American FrontiersNo ratings yet

- What Makes the Middle East Tick: Insights of a DiplomatFrom EverandWhat Makes the Middle East Tick: Insights of a DiplomatNo ratings yet

- Paradigms of Style - A Study of Zulfikar Ghoses Novels PDFDocument196 pagesParadigms of Style - A Study of Zulfikar Ghoses Novels PDFJeselyn Requioma100% (1)

- Youth and History: Tradition and Change in European Age Relations, 1770–PresentFrom EverandYouth and History: Tradition and Change in European Age Relations, 1770–PresentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 19 (2) PL99-114Document16 pages19 (2) PL99-114Muhammad YasruNijarNo ratings yet

- Between Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary LivesFrom EverandBetween Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary LivesNo ratings yet

- Theorizing The DiasporaDocument13 pagesTheorizing The Diasporasalomaoalexandre coelhoNo ratings yet

- Going Solo Chapter 1Document14 pagesGoing Solo Chapter 1Southern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Ucsp 1st Exam 2 Way TosDocument22 pagesUcsp 1st Exam 2 Way TosAnne Besin-LaquianNo ratings yet

- Homecomer - SchutzDocument9 pagesHomecomer - SchutzrmancillNo ratings yet

- Transformation and African Migrants: The Conflicting Worlds of Cultural Beliefs and Marriage Issues in No Longer at Ease Andchairman of FoolsDocument8 pagesTransformation and African Migrants: The Conflicting Worlds of Cultural Beliefs and Marriage Issues in No Longer at Ease Andchairman of FoolsJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICSNo ratings yet

- Home and Away: Self-Reflexive Auto-/Ethnography: Christiane Kraft AlsopDocument12 pagesHome and Away: Self-Reflexive Auto-/Ethnography: Christiane Kraft AlsopAlan WhaleyNo ratings yet

- The Hindus As They AreDocument165 pagesThe Hindus As They AredundunNo ratings yet

- Islam - Essays in The Nature and Growth of A Cultural Tradition (1955), G. E. Von GrunebaumDocument525 pagesIslam - Essays in The Nature and Growth of A Cultural Tradition (1955), G. E. Von GrunebaumRaas4555No ratings yet

- Travelling towards Home: Mobilities and HomemakingFrom EverandTravelling towards Home: Mobilities and HomemakingNicola FrostNo ratings yet

- America S Melting Pot ReconsideredDocument28 pagesAmerica S Melting Pot ReconsideredMarcio OliveiraNo ratings yet

- ⑩文学部紀要 第44号 - 123-136Document14 pages⑩文学部紀要 第44号 - 123-136Kim NgânNo ratings yet

- Doing Life Histories and Biographical ResearchDocument6 pagesDoing Life Histories and Biographical ResearchAshary C. H. Solaiman64% (14)

- Culture Shock Due To Contact With Unfamiliar CulturesDocument12 pagesCulture Shock Due To Contact With Unfamiliar CulturesÀmmèlìà DìpùNo ratings yet

- Brazil, the promised land: The most fantastic Jewish migration storyFrom EverandBrazil, the promised land: The most fantastic Jewish migration storyNo ratings yet

- Tough Choices: Structured Paternalism and the Landscape of ChoiceFrom EverandTough Choices: Structured Paternalism and the Landscape of ChoiceRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- The Jere Beasley Report, Jan. 2009Document52 pagesThe Jere Beasley Report, Jan. 2009Beasley AllenNo ratings yet

- Land Back MovementDocument10 pagesLand Back MovementfbgngnNo ratings yet

- The Solution To The Global Food CrisisDocument5 pagesThe Solution To The Global Food CrisisAb RehmanNo ratings yet

- Athe Age of Jackson Trends and Themes of The EraDocument11 pagesAthe Age of Jackson Trends and Themes of The EraMuhammad SaadNo ratings yet

- Thoreau and Banksy - Civil DisobedienceDocument7 pagesThoreau and Banksy - Civil Disobedienceselina_kollsNo ratings yet

- Application File Created For:: EmiliaDocument7 pagesApplication File Created For:: EmiliaEmilia CassidyNo ratings yet

- Evening Reception For Karen BassDocument1 pageEvening Reception For Karen BassSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Regents of The University of California Et Al v. Dept of Homeland Security Et Al OpinionDocument49 pagesRegents of The University of California Et Al v. Dept of Homeland Security Et Al OpinionDoug MataconisNo ratings yet

- Mapping Directions-POLICY REPORTDocument48 pagesMapping Directions-POLICY REPORTlauramullaneNo ratings yet

- Reading Response #2Document4 pagesReading Response #2kevin morenoNo ratings yet

- Note Packet - Road To IndependenceDocument8 pagesNote Packet - Road To Independencemattmoore83No ratings yet

- Coast Artillery Journal - Aug 1932Document84 pagesCoast Artillery Journal - Aug 1932CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Now The End Begins!Document25 pagesNow The End Begins!Total Surveillance And The Mark Of The Beast (666)No ratings yet

- Interracial Marriage Research Essay FixedDocument8 pagesInterracial Marriage Research Essay Fixedapi-302952196No ratings yet

- 2nd Declaration of Independence of The 50 StatesDocument11 pages2nd Declaration of Independence of The 50 StatesDarryl Brown100% (16)

- One Hundred Years of US Intervention by Zoltan GrossmanDocument7 pagesOne Hundred Years of US Intervention by Zoltan GrossmanDragan NikolicNo ratings yet

- Zialcita PDFDocument10 pagesZialcita PDFSagradah FamiliaNo ratings yet

- AP History NotesDocument153 pagesAP History NotesvirjogNo ratings yet

- US Grand Strategy & Realism - Stephen WaltDocument20 pagesUS Grand Strategy & Realism - Stephen Waltsaif khanNo ratings yet

- 2012 Report To CongressDocument509 pages2012 Report To CongressĐinh Minh ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Indentured Labour: Indigenous TribesDocument9 pagesIndentured Labour: Indigenous TribesShubhamNo ratings yet

- Race and Color Jamaican Migrants in London and New York CityDocument21 pagesRace and Color Jamaican Migrants in London and New York Citykismetdoll100% (1)

- Annexure II 2014.2Document1,153 pagesAnnexure II 2014.2anandsilverNo ratings yet

- ResourceResourceADocument322 pagesResourceResourceASergey PostnykhNo ratings yet

- (Brian K. Obach) Labor and The Environmental MovemDocument351 pages(Brian K. Obach) Labor and The Environmental MovemhanifNo ratings yet

- What Is Public DiplomacyDocument24 pagesWhat Is Public DiplomacyJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- M-40k Notice of Denial of Expedited FS or Inability To Issue FSDocument1 pageM-40k Notice of Denial of Expedited FS or Inability To Issue FShooNo ratings yet

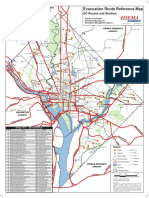

- D.C.-Area Evacuation Route Reference MapDocument2 pagesD.C.-Area Evacuation Route Reference Mapwamu885No ratings yet

- Jafeth Antonio Sanjuanelo Angarita - Marketing & Advertising Across Different CulturesDocument3 pagesJafeth Antonio Sanjuanelo Angarita - Marketing & Advertising Across Different CulturesMaria Camila Fuentes ReyesNo ratings yet

- The Development of Milwaukee's Community Conferencing ProgramDocument26 pagesThe Development of Milwaukee's Community Conferencing ProgramThe International Journal of Conflict & ReconciliationNo ratings yet