Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination Reference Guide

Uploaded by

biotech_vidhya0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views41 pagesscience

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentscience

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

41 views41 pagesPediatric Eye and Vision Examination Reference Guide

Uploaded by

biotech_vidhyascience

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 41

Reference G uide

for O ptom etrists

Optometric Clinical

Practice Guideline

PED IATRIC

EYE A N D VISIO N

EXA M IN ATIO N

Revised edition for the C anadian A ssociation of O ptom etrists printed w ith perm ission of the

A m erican A ssociation of O ptom etrists

A m erican O ptom etric A ssociation 1994, 2002. 243 N . Lindbergh Blvd., St. Louis, M O 63141-7881

First Edition O riginally Prepared by (and Second Edition Review ed by) the A m erican O ptom etric

A ssociation C onsensus Panel on Pediatric Eye and Vision Exam ination:

M itchell M . Scheim an, O .D ., M .S., Principal A uthor

C atherine S. A m os, O .D .

Elise B. C iner, O .D .

W endy M arsh-Tootle, O .D .

Bruce D . M oore, O .D .

M ichael W . Rouse, O .D ., M .S.

Review ed by the A O A C linical G uidelines C oordinating C om m ittee:

John C . Tow nsend, O .D ., C hair (2nd Edition)

John F. A m os, O .D ., M .S. (1st and 2nd Editions)

Kerry L. Beebe, O .D . (1st Edition)

Jerry C avallerano, O .D ., Ph.D . (1st Edition)

John Lahr, O .D . (1st Edition)

W . H ow ard M cA lister, O .D ., M .P.H . (2nd Edition)

Stephen C . M iller, O .D . (2nd Edition)

Richard W allingford, Jr., O .D . (1st Edition)

A pproved by the A O A Board of Trustees June 23, 1994 (1st Edition), Revised Septem ber 1997,

and A pril 25, 2002 (2nd Edition)

Review and revision for C anadian printing:

D eborah Jones, O .D ., FC O ptom , D ipC LP, FA A O

OPTOMETRY: THE PRIMARY EYE CARE PROFESSION

D octors of optom etry are independent prim ary health care providers w ho

exam ine, diagnose, treat, and m anage diseases and disorders of the visual

system , the eye, and associated structures as w ell as diagnose related sys-

tem ic conditions.

O ptom etrists provide m ore than tw o-thirds of the prim ary eye care services

in the U nited States and C anada. They are m ore w idely distributed geo-

graphically than other eye care providers and are readily accessible for the

delivery of eye and vision care services. There are approxim ately 3,500 full-

tim e doctors of optom etry currently in practice in C anada. O ptom etrists

practice in alm ost 900 com m unities across C anada

The m ission of the profession of optom etry is to fulfill the vision and eye

care needs of the public through clinical care, research, and education, all

of w hich enhance the quality of life.

N O TE: C linicians should not rely on this C linical G uideline alone for patient care and

m anagem ent. Refer to the listed references and other sources for a m ore detailed

analysis and discussion of patient care inform ation. The inform ation in the G uideline is

current as of date of publication. It w ill be review ed periodically and revised as needed.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1

II. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

A . Epidem iology of Eye and Vision D isorders in C hildren ..... 3

B. The Pediatric Eye and Vision Exam ination...................... .. 4

III. CARE PROCESS

A . Exam ination of Infants and Toddlers ......................... 6-12

1. G eneral C onsiderations

2. Early D etection and Prevention

3. Exam ination Sequence

a. Patient H istory

b. Visual A cuity

c. Refraction

d. Binocular Vision and O cular M otility

e. O cular H ealth A ssessm ent and System ic

H ealth Screening

f. A ssessm ent and D iagnosis

B. Exam ination of Preschool C hildren .......................... 12-17

1. G eneral C onsiderations

2. Early D etection and Prevention

3. Exam ination Sequence

a. Patient H istory

b. Visual A cuity

c. Refraction

d. Binocular Vision, A ccom m odation, and

O cular M otility

e. O cular H ealth A ssessm ent and System ic

H ealth Screening

f. Supplem ental Testing

g. A ssessm ent and D iagnosis

C . Exam ination of School-A ge C hildren ....................... 17-20

1. G eneral C onsiderations

2. Early D etection and Prevention

3. Exam ination Sequence

a. Patient H istory

b. Visual A cuity

c. Refraction

d. Binocular Vision, A ccom m odation, and O cular

M otility

e. O cular H ealth A ssessm ent and System ic H ealth

Screening

f. Supplem ental Testing

g. A ssessm ent and D iagnosis

D . M anagem ent of C hildren ...................................... 20-22

1. Patient Education

2. C oordination, Frequency, and Extent of C are

IV. CONCLUSION .......................................................................... 23

V. REFERENCES ...................................................................... 25-30

VI. APPENDICES & RESOURCES............................................... 31-37

Figure 1: Pediatric Eye and Vision Exam ination: A Brief Flow chart

Figure 2: Potential C om ponents of the Eye and Vision Exam ination for Infants and

Toddlers

Figure 3: Potential C om ponents of the Eye and Vision Exam ination for Preschool

C hildren

Figure 4: Potential C om ponents of the Eye and Vision Exam ination for School-A ge

C hildren

A bbreviations of C om m only U sed Term s ................................................ 35

G lossary ................................ ........................................................... 36-37

1.

I. INTRODUCTION

O ptom etrists, through their clinical education, training, experience, and broad geo-

graphic distribution, have the m eans to provide effective prim ary eye and vision

services to children in C anada. Prim ary care has been described as those services

provided to patients by a health care practitioner "w ho know s them , w ho is avail-

able for first contact and continuing care, and w ho offers a portal of entry to spe-

cialists for those conditions w arranting referral."

1

Eye care serves as an im portant

point of entry into the health care system because:

Virtually all people need eye care services at som e tim e in their lives.

By its very nature, eye care provides for the evaluation, assessm ent, and coordi-

nation of a broad spectrum of health care needs.

Eye care is a nonthreatening form of health care, particularly to patients w ho

are reluctant to seek general or preventive m edical care.

2

This O ptom etric C linical Practice G uideline for the Pediatric Eye and Vision

Exam ination describes appropriate exam ination procedures for evaluation of the

eye health and vision status of infants and children to reduce the risk of vision loss

and facilitate norm al visual developm ent. It contains recom m endations for tim ely

diagnosis, intervention, and, w hen necessary, consultation or referral for treatm ent

by another health care provider. This G uideline w ill assist optom etrists in achieving

the follow ing goals:

D evelop an appropriate tim etable for eye and vision exam inations for pediatric

patients

Select appropriate exam ination procedures for all pediatric patients

Exam ine the eye health and visual status of pediatric patients effectively

M inim ize or avoid the adverse effects of eye and vision problem s in children

through early identification, education, treatm ent, and prevention

Inform and educate patients, parents/caregivers, and other health care providers

about the im portance and frequency of pediatric eye and vision exam inations.

II. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

In 2003 the C anadian C ensus Bureau reported that there w ere 7.9 m illion children

under 19 years of age in the C anada (25% of the population).

3

In the U nited

States, vision disorders are the fourth m ost com m on disability and the m ost preva-

lent handicapping condition during childhood.

4

In spite of the high prevalence of

vision disorders in this population, studies show that only about 31 percent of chil-

dren betw een ages 6 and 16 years are likely to have had a com prehensive eye and

vision exam ination w ithin the past year, w hile below the age of 6, only about 14

percent are likely to have had an eye and vision exam ination.

5

In a study of 5,851

children 9 to 15 years of age, nearly 20 percent needed glasses but only 10 percent

of that group already had them .

6

Thus, 90 percent of those children requiring pre-

scription eyeglasses w ere not w earing them . W hy so few children receive profes-

sional eye care is unknow n. Possible explanations include a reliance on pediatri-

2.

cians, other prim ary care physicians, or school screenings, m any uninsured parents'

or caregivers' inability to pay for the needed services, and parents' or caregivers'

lack of know ledge that early professional eye care is needed to prevent unnecessary

loss of vision as w ell as to potentially im prove educational readiness.

U nfortunately, undue reliance on vision screening by pediatricians or other prim ary

care physicians m ay result in the late detection of am blyopia and other vision disor-

ders. O ne study reported that in a sam ple of 102 private pediatric practices , vision

screening w as attem pted on only 38 percent of 3-year-old children and 81 percent

of 5-year-old children. The study also show ed that only 26 percent of children fail-

ing the A m erican A cadem y of Pediatrics vision screening guidelines w ere referred

for a professional eye exam ination.

7

The A m erican Public H ealth A ssociation

adopted a resolution that recognizes the shortcom ings of vision screenings, encour-

ages regular eye exam inations at the ages of 6 m onths, 2 years, and 4 years, and

urges pediatricians to recom m end that all children receive eye exam inations at

these intervals.

8

These recom m endations have been adopted by the C anadian

A ssociation of O ptom etrists and prom oted to the profession and the general public

during C anadian Eye H ealth M onth in O ctober 2003.

The interrelationships betw een vision problem s and learning difficulties and the

cost of undetected vision problem s to society are of concern.

9

Vision problem s

generally are not the direct cause of learning disorders; how ever, they can interfere

w ith children's abilities to perform to their potential. W hen children fail to progress

in school, the cost to the individual and society can be substantial.

A m blyopia is the m ost com m on cause of poor vision in the under 20 age group

(G rounds 1995).

10

Studies have show n the need for earlier eye exam ination and

treatm ent and have resulted in clinical advances that enable m ore effective preven-

tive eye care for infants and preschool children.

11-21

Extensive research has dem on-

strated the im portance of the first few years of life in the developm ent of vision.

W ithin the first 6 m onths of life, rapid changes occur in m ost com ponents of the

visual system including visual acuity,

11,12

accom m odation,

13,14

and binocular vision.

15-

17

Interference w ith developm ent during this very critical phase m ay lead to serious

lifelong effects on vision.

18

Successful treatm ent can be obtained m ore quickly w ith

early intervention.

21-24

A n outgrow th of this research is the developm ent of new clinical procedures appro-

priate for the evaluation of vision in infants and toddlers.

17,25-36

C linicians have

gained a better understanding of both the characteristics and processes of vision

developm ent in infants and the tools necessary to exam ine them . A s a result, it is

now recom m ended that all children receive regular, professional eye care beginning

at 6 m onths of age after an initial eye screening at birth, typically perform ed by the

pediatrician.

8,37

3.

A. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF EYE AND VISION DISORDERS IN CHILDREN

O ne of the largest studies reporting the prevalence of specific vision disorders in

children w as conducted as part of the H ealth Exam ination Surveys of 1963-65.

38

D ata w ere collected from a sam ple of 7,119 non-institutionalized children 6-11

years of age w ho received standardized eye exam inations. O f the children exam -

ined, 9.2 percent had an eye m uscle im balance, a disease condition, or other

abnorm ality in one or both eyes. A pproxim ately 2.4 percent had constant strabis-

m us and 4.3 percent had significant heterophoria. The com bined prevalence of

eyelid conditions (hordeola, conjunctivitis, and blepharitis) w as about 1 percent.

The second phase of that research project determ ined the prevalence of eye disor-

ders in 12- to 17-year-olds.

39

O f the 6,768 children exam ined, 7.9 percent had an

eye m uscle im balance, a disease condition, or other abnorm ality in one or both

eyes; approxim ately 3.4 percent had constant strabism us, and 1.8 percent had sig-

nificant heterophoria. The prevalence of conjunctivitis w as 0.6 percent, and that of

blepharitis, 0.3 percent.

A m ore recent review of the literature found the follow ing prevalence figures for

eye and vision problem s in children: am blyopia, 2-3 percent; strabism us, 3-4 per-

cent; refractive errors, 15-30 percent; and ocular disease, less than 1 percent.

40

A

large-scale prospective study of the prevalence of vision disorders and ocular dis-

ease focused on a clinical population of children betw een the ages of 6 m onths

and 18 years. C om prehensive eye exam inations perform ed on 2,025 consecutive

patients show ed that, in addition to refractive anom alies, the m ost com m on condi-

tions optom etrists are likely to encounter in this population are binocular vision and

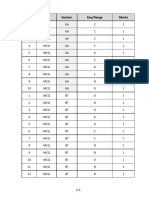

accom m odative disorders (see Table 1).

41

H yperopia 33% 23%

A stigm atism 22.5% 22.5%

M yopia 9.4% 20.2%

N onstrabism ic binocular

disorders

5.0% 16.3%

Strabism us 21.1% 10.0%

A m blyopia 7.9% 7.8%

A ccom m odative disorders 1.0% 6.0%

Peripheral retinal abnorm alities

requiring referral or follow -up care

0.5% 2.0%

VISIO N D ISO RD ERS IN A C LIN IC A L PO PU LATIO N O F C H ILD REN

Disorder Ages 6 months to

5 years 11 months

Ages 6 years

to 18 years

Table 1

4.

B. THE PEDIATRIC EYE AND VISION EXAMINATION

The term "pediatric population" can be applied to patients w ithin a broad age

range, including all those betw een birth and 18 years of age. A lthough the capa-

bilities and needs of children vary significantly, the pediatric population can be

divided into three subcategories:

42-44

Infants and toddlers (birth to 2 years, 11 m onths)

Preschool children (3 years to 5 years, 11 m onths)

School-age children (6 to 18 years).

This subdivision of the pediatric population is based on the developm ental changes

that occur from birth through childhood. C linical experience and research have

show n that at 6 m onths the average child has reached a num ber of critical devel-

opm ental m ilestones, m aking this an appropriate age for the first eye and vision

exam ination. A t this age the average child can sit up w ith support and cognitively

is concerned w ith im m ediate sensory experiences.

45

Visual acuity,

12

accom m oda-

tion,

13,14

stereopsis, and other aspects of the infant's visual system have developed

rapidly, reaching adult levels by the age of 6 m onths (see Table 2, p 5).

15,25

A t about 3 years of age children have achieved adequate receptive and expressive

language skills to begin to cooperate for som e of the traditional eye and vision

tests. H ow ever, the exam iner often needs to m ake m odifications in the testing to

gather useful inform ation. By 6 years of age, the child has m atured to the point

that m any adult tests can be used, w ith m inor procedural m odifications. Because a

child can vary significantly from expected age norm s, it is im portant not to rely

solely upon chronological age w hen choosing testing procedures. A ppropriate test

procedures need to be based on the child's developm ental age and specific capabil-

ity.

The goals of the pediatric eye and vision exam ination are several (see A ppendix

Figure 1):

Evaluate the functional status of the eyes and visual system , taking into

account each child's level of developm ent

A ssess ocular health and related system ic health conditions

Establish a diagnosis and form ulate a treatm ent plan

C ounsel and educate parents/caregivers regarding their child's visual,

ocular, and related health care status, including recom m endations for

treatm ent, m anagem ent, and preventive care.

5.

T

a

b

l

e

2

6.

III. CAREPROCESS

A. EXAMINATION OF INFANTS AND TODDLERS

1. General Considerations

This section of the G uideline describes optom etric procedures for exam ining infants

and toddlers from birth to 2 years, 11 m onths of age. The exam ination com po-

nents are described in general term s and are not intended to be all inclusive.

Professional judgm ent and individual patient sym ptom s, findings, and cooperation

m ay have significant im pact on the nature and course of the exam ination.

C hildren in this age group generally perform best if the exam ination takes place

w hen they are alert. Exam ination early in the m orning or after an infant's nap is

usually m ost effective. Because infants tend to be m ore cooperative and alert

w hen feeding, it is also helpful to suggest that the parent bring a bottle for the

child.

A ge-appropriate exam ination and m anagem ent strategies should be used. M ajor

m odifications include relying m ore on objective exam ination procedures and per-

form ing tests considerably m ore rapidly than w ith older children.

43

2. Early Detection and Prevention

Early detection and treatm ent are essential to preventing vision conditions that

have the potential to cause perm anent loss of vision. Screening by the pediatrician

or other prim ary care physician is im portant at birth and during the first 6 m onths

of life w hen the visual system is highly susceptible to interference. H ow ever,

screening this population has been problem atic, leading to underdetection of stra-

bism us, am blyopia, and significant refractive error.

5,46

N ew er screening techniques

such as photorefraction are available,

36, 47-50

but until they are validated, an eye and

vision exam ination at 6 m onths of age is the best approach for early detection and

prevention of eye and vision problem s in infants and toddlers (see Table 2, p5).

3. Examination Sequence

The eye and vision exam ination of the infant or toddler m ay include, but is not lim -

ited to, the follow ing procedures (see A ppendices Figure 2):

a. Patient History

A com prehensive patient history for infants and toddlers m ay include:

N ature of the presenting problem , including chief com plaint

Visual and ocular history

G eneral health history, including prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal history

and review of system s

Fam ily eye and m edical histories

D evelopm ental history of the child.

7.

The collection of dem ographic data generally precedes the taking of the patient

history. H aving the parent(s) fill out a questionnaire facilitates obtaining the patient

history.

43

Responses to questions related to the m other's pregnancy, birth of the

child, and the child's general and vision developm ent w ill help direct the rem ainder

of the exam ination.

b. Visual Acuity

A ssessm ent of visual acuity for infants and toddlers m ay include these procedures:

Fixation preference tests

Preferential looking visual acuity test.

Estim ation of visual acuity in an infant or toddler can help to confirm or reject cer-

tain hypotheses about the level of binocularity and provides direction for the

rem ainder of the exam ination. Because subjective visual acuity testing requiring

verbal identification of letters or sym bols dem ands sustained attention, this test

cannot be used w ith infants and toddlers. H ow ever, other tests m ay be used to

m ake assum ptions about visual acuity. For exam ple, w hen a unilateral, constant

strabism us is present, visual acuity is presum ed to be reduced in the strabism ic eye.

In the presence of a constant, alternating strabism us, visual acuity is likely to be

norm al in both eyes.

In the absence of strabism us, fixation preference testing w ith a vertical base up or

base dow n 10 prism diopter (PD ) lens to create diplopia has been show n to be

effective in detecting about a three-line visual acuity difference betw een the eyes

and identifying m oderate to severe am blyopia.

51

Specific clinical guidelines have

been developed to estim ate visual acuity on the basis of the strength of fixation

preference.

52, 53

A study of fixation preference testing dem onstrated that the fixa-

tion pattern can be rapidly assessed and confirm ed the usefulness of a graded

assessm ent of the binocular fixation pattern in the detection of am blyopia.

54

Before the advent of behavioral and electrophysiological procedures, indirect m eth-

ods w ere all that w ere available to clinicians for assessing visual acuity in preverbal

children. A s m ore direct assessm ent procedures w ere developed, it becam e evident

that although fixation preference is helpful in detecting am blyopia, it is not alw ays

an accurate predictor of visual acuity. Preferential looking acuity and fixation pref-

erence do not show a strong association.

55,56

C linical use of preferential looking acuity is generally very successful. Teller acuity

cards can be used w ith infants and young children until they are ready for m ore

subjective testing.

33,57 59

H ow ever, underestim ation of visual acuity loss in patients

w ith strabism ic am blyopia on the basis of grating acuity (preferential looking acuity)

lim its the usefulness of this test.

60-65

W hen in doubt, the optom etrist can refer the

child for electrodiagnostic testing, such as visual evoked potentials, w hich has been

show n to be an im portant m ethod for direct assessm ent of visual acuity in

infants.

66-68

8.

If clinical evaluation of an infant or toddler by indirect visual acuity testing, refrac-

tion, and ocular health assessm ent indicates any problem w ith visual acuity, forced-

choice preferential looking w ith the Teller acuity cards or electrodiagnostic testing

should be considered to obtain a m ore precise m easure of baseline visual acuity.

C onsultation w ith an optom etrist or ophthalm ologist w ho has advanced clinical

training or experience w ith preferential looking assessm ent or electrophysiological

evaluation of visual acuity m ay be w arranted.

c. Refraction

Traditional subjective procedures for the assessm ent of refractive error m ay be inef-

fective w ith infants or toddlers because of short attention span and poor fixation.

69

A s a result, the exam iner w ill need to rely on objective m easures of refraction. The

tw o m ost com m only used procedures are:

C ycloplegic retinoscopy

N ear retinoscopy.

It is im portant for the exam iner perform ing cycloplegic retinoscopy in an infant or

toddler to take several precautions:

70

Select the cycloplegic agent carefully (e.g., fair-skinned children w ith blue

eyes m ay exhibit an increased response to drugs and darkly pigm ented

children m ay require m ore frequent or stronger dosages).

Avoid overdosage (e.g., children w ith D ow n syndrom e, cerebral palsy,

trisom y 13 and 18, and other central nervous system disorders in w hom

there m ay be an increased reaction to cycloplegic agents, 1% tropicam ide

m ay be used).

Be aw are of biologic variations in children (e.g., low w eight infants m ay

require a m odified dosage).

C yclopentolate hydrochloride* is the cycloplegic agent of choice. O ne drop should

be instilled tw ice, 5 m inutes apart, in each eye, using a strength of 0.5% for chil-

dren from birth to 1 year and 1% for older children.

71

Spray adm inistration of the

drug appears to be a viable alternative to the use of conventional eye drops for

routine cycloplegic retinoscopy in the pediatric population.

72-74

The child is asked to

keep his or her eyes gently closed w hile the exam iner sprays the cycloplegic agent

on the child's eyelids. A s the child blinks, enough of the drug is delivered to the

eye to provide adequate cycloplegia.

* Every effort has been m ade to ensure that drug dosage recom m endations are accurate at

the tim e of publication of this G uideline. H ow ever, treatm ent recom m endations change due

to continuing research and clinical experience, and clinicians should verify drug dosage

schedules w ith product inform ation sheets. Drugs must be administered in accordance with

provincial regulations.

9.

This technique has tw o advantages: (1) The child has less of an avoidance

response, and it m ay be less traum atic for the child and the parent observing the

procedure. (2) A single application can achieve both cycloplegia and pupillary dila-

tion w hen a m ixture of 0.5% cyclopentolate, 0.5% tropicam ide, and 2.5%

phenylephrine is used. To m aintain sterility, it is best to have this spray m ixture pre-

pared by a pharm acist. Retinoscopy m ay be perform ed 20-30 m inutes after instilla-

tion.

72

The use of loose lenses or a lens rack is recom m ended for retinoscopy.

A study com paring retinoscopy in infants using near retinoscopy, cycloplegia w ith

tropicam ide 1% , and cycloplegia w ith cyclopentolate 1% found that tropicam ide

m ay be a useful alternative in m any healthy, nonstrabism ic infants.

75

N ear retinoscopy is another objective m ethod of estim ating refractive error in

infants and toddlers.30 H ow ever, it has not been found reliable for quantification

of the refractive error.

76-78

N ear retinoscopy m ay have som e clinical value in the follow ing situations:

W hen frequent follow -up is necessary

W hen the child is extrem ely anxious about instillation of cycloplegic agents

W hen the child has had or is at risk for an adverse reaction to cyclopento

late or tropicam ide.

The average refractive error in children from birth to 1 year of age is about 2

diopters (D ) of hyperopia (standard deviation 2 D ).

79

A stigm atism up to 2 D is com -

m on in children under 3 years of age. Studies show that 30-50 percent of infants

less than 12 m onths of age have significant astigm atism , w hich declines over the

first few years of life, becom ing stable by approxim ately 2 to 5 years of age.

80-81

Low am ounts of anisom etropia are com m on and variable in infants. The clinician

m ay choose to m onitor these levels of refractive error rather than prescribe a lens

correction.

d. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility

The follow ing procedures are useful for assessing binocular function:

C over test

H irschberg test

Krim sky test

Brckner test

Versions

N ear point of convergence.

The cover test is the procedure of choice for evaluation of binocular vision in pre-

verbal children because it is objective and requires little tim e to adm inister. If the

cover test results are unreliable because of the child's resistance to testing, other

m ethods m ay be used. In such cases, use of the H irschberg test is often successful

in infants 6 m onths and younger. Prism s can be used w ith the H irschberg test to

10.

align the corneal reflections (Krim sky test) and determ ine the m agnitude of the

deviation.

The Brckner test is another m eans of objectively assessing binocular vision, as w ell

as providing an indirect evaluation of refractive error. W hen both eyes are sim ulta-

neously illum inated w ith the ophthalm oscope beam at a distance of 100 cm , an

overall w hitening of the red reflex across the entire pupil of one eye indicates stra-

bism us or anisom etropic am blyopia. W hile the absence of a Brckner reflex is not

a good indication of alignm ent, the presence of a Brckner reflex is considered a

positive result, and is a good indication of strabism us, even of sm all am ounts.

O nce detected w ith the Brckner reflex, the deviation should be quantified w ith

the cover test or Krim sky technique.

A dditional binocular testing often can be perform ed successfully w ith infants and

toddlers. For exam ple, preferential looking techniques can be used to assess stere-

opsis w ith som e success.

17, 82,83

A ssessm ent of extraocular m uscle function and concom itancy m ay involve version

testing w ith an appropriate target. If the infant w ill follow a penlight, observation

of the corneal reflections in all cardinal positions of gaze is possible. W hen a prob-

lem is suspected, the cover test procedure should be used for the position of gaze

in question. A fter perform ing version testing, the clinician m ay find it useful to

m ove the penlight or other target tow ard the child to assess objectively the near

point of convergence (N PC ).

If a binocular vision disorder or an ocular m otility problem is suspected, consulta-

tion w ith an optom etrist or ophthalm ologist w ho has advanced clinical training or

experience w ith this population m ay be w arranted.

e. Ocular Health Assessment and Systemic Health Screening

A n evaluation of ocular health m ay include:

Evaluation of the ocular anterior segm ent and adnexa

Evaluation of the ocular posterior segm ent

A ssessm ent of pupillary responses

Visual field screening (confrontation).

The diagnosis of eye disease in infants and toddlers presents som e unique chal-

lenges. Standard procedures such as biom icroscopy, tonom etry, and binocular indi-

rect ophthalm oscopy are considerably m ore difficult in this population.

The cover test and versions, both im portant binocular vision assessm ent proce-

dures, are also im portant for ocular health assessm ent. For exam ple, the presence

of strabism us m ay indicate any num ber of disease entities such as neoplasm , neu-

rom uscular disorder, infection, vascular anom aly, or traum atic dam age.

84

11.

The exam iner perform ing external ocular evaluation should gather as m uch infor-

m ation as possible by gross inspection of the eyes and adnexa. G enerally, children

up to the age of 6-9 m onths are sufficiently attracted to lights to perm it adequate

evaluation using a penlight or transillum inator. W ith the older infant, it is im por-

tant to use a variety of interesting targets that can be attached to the transillum ina-

tor.

84

Pupil function (direct, consensual, and afferent pupil integrity) should also be

evaluated.

A hand-held biom icroscope m ay be used for evaluation of the anterior segm ent or

the parent/caregiver m ay be able to position and hold the infant or toddler in a

standard biom icroscope. If a corneal problem is suspected, but use of the biom i-

croscope is im possible, the optom etrist m ay attem pt an exam ination using sodium

fluorescein and a Burton lam p. A nother sim ple alternative is to use a self-illum inat-

ed, hand-held m agnifying lens, or a 20 D condensing lens w ith a light source.

Thorough evaluation of the ocular m edia and the posterior segm ent generally

requires pupillary dilation. Recom m ended drugs and dosages for pupillary dilation

in infants and toddlers are one drop each of tropicam ide (0.5% ) or cyclopentolate

(0.5% ) and one drop of phenylephrine (2.5% ).

84*

The spray m ixture discussed pre-

viously is effective in achieving both dilation and cycloplegia in the pediatric popu-

lation.

72

Both direct and binocular indirect ophthalm oscopy m ay be perform ed

after the pupil has dilated. A n ideal tim e for evaluation of the posterior segm ent is

w hen the infant is in a calm , relaxed, sedated condition (i.e., being bottle fed or

sound asleep).

44

W hen adequate fundus exam ination is im possible but is indicated

by patient history, exam ination under sedation or anesthesia m ay be w arranted.

M easuring intraocular pressure (IO P) is not a routine part of the eye exam ination of

the infant or toddler. A lthough it is extrem ely rare in this age group, glaucom a

m ay be suspected in the presence of a num ber of signs (e.g., corneal edem a,

increased corneal diam eter, tearing, and m yopia). M easurem ent of IO P is difficult

and the results often are unreliable.

43,85

H ow ever, pressure should be assessed

w hen ocular signs and sym ptom s or risk factors for glaucom a exist. M easurem ent

of IO P in the pediatric population m ay be accom plished w ith hand-held applana-

tion and noncontact tonom eters. If risk factors are present and reliable assessm ent

of IO P under standard clinical conditions is im possible, testing under sedation m ay

be appropriate.

W hen strabism us or other neurological problem s are suspected, confrontation visu-

al fields should be attem pted w ith infants and toddlers using a variation of the tra-

ditional approach.

86

A shift in fixation, head m ovem ent tow ard the target, or

change in facial expression of the infant can indicate that the target has m oved

from an unsighted to a sighted field.

43

The clinician should decide w hen im aging

studies are indicated, independently or in consultation w ith a neurosurgeon or neu-

rologist, on the basis of risk factors and the observation of ocular abnorm alities, or

signs such as nystagm us, developm ental delay, poor grow th, regression of skills,

and seizures.

* Drugs must be administered in accordance with provincial regulations.

12.

D uring the ocular health assessm ent and system ic health screening of infants and

children of any age, it is im portant to rem em ber that health care providers are

responsible for recognizing and reporting signs of child abuse, a significant problem

in the U nited States. Betw een 1990 and 1994 reported child abuse cases increased

27 percent, from 800,000 to 1,012,000, w ith alm ost half of the victim s under the

age of 6 years.

87

O ptom etrists have a uniquely im portant role in diagnosing child abuse including

Shaken Baby Syndrom e (SBS) because external eye traum a, and retinal traum a

(hem orrhages, folds, tears, detachm ents, and schisis) are com m on ocular findings

from child abuse.

88-90

SBS is a specific term used to describe a form of child abuse

in w hich the child is injured secondary to violent shaking, w hich often causes reti-

nal hem orrhaging. M ost often the child is betw een 2 and 18 m onths of age at the

tim e of abuse.

91,92

Suspected cases of child abuse should be reported to the appropriate authority.

This m ay be a social w orker associated w ith the fam ily or the child protection

agency. suspected child abuse or Failure to report a suspected case of child abuse

puts that child, his or her other siblings, and possibly a parent/caregiver in danger

of continued abuse at hom e.

f. Assessment and Diagnosis

U pon com pletion of the exam ination, the optom etrist assesses and evaluates the

data to arrive at one or m ore diagnoses and establishes a m anagem ent plan. In

som e cases, referral for consultation w ith or treatm ent by another optom etrist, the

patient's pediatrician, prim ary care physician, or other health care provider m ay be

indicated.

B. EXAMINATION OF PRESCHOOL CHILDREN

1. General Considerations

This section of the G uideline describes the optom etric exam ination procedures for

preschool children. The exam ination com ponents are discussed in general term s

and are not intended to be all inclusive. Professional judgm ent and individual

patient history, sym ptom s, findings, and cooperation m ay have significant im pact

on the nature and course of the exam ination.

A lthough the vast m ajority of children in this age group can com m unicate verbally,

it is preferable in m ost cases for the parent/caregiver to accom pany the child into

the exam ination room . It is im portant to ensure that the child feels relaxed and at

ease, w hich is often best accom plished by beginning the exam ination w ith proce-

dures that appear less threatening.

A ge-appropriate exam ination and m anagem ent strategies should be used w ith pre-

school children. M ajor m odifications include reliance on objective exam ination

techniques, lim ited use of subjective techniques requiring verbal interaction, and

13.

perform ing testing considerably m ore rapidly than is typically used for older chil-

dren.

2. Early Detection and Prevention

A com m on approach to early detection and prevention of vision problem s in pre-

school children is vision screening by pediatricians or other prim ary care physicians

or lay screeners. Screenings for this population are less problem atic than for

infants and toddlers because som e subjective testing is possible; how ever, screen-

ings are less accurate for preschool children than for older children.

93-95

Reasonably

accurate screening tests are available for the assessm ent of m any visual functions.

The problem w ith m any vision screenings, how ever, is that they are lim ited in

scope. They m ay detect only visual acuity problem s and m ay fail to detect other

im portant vision problem s, leading to parents' or caregivers' false sense of security.

A com prehensive eye exam ination at 3 years of age continues to be the m ost effec-

tive approach to prevention or early detection of eye and vision problem s in the

preschool child.

3. Examination Sequence

The pediatric eye and vision exam ination of the preschool child m ay include, but is

not lim ited to, the follow ing (see A ppendices Figure 3):

a. Patient History

A com prehensive patient history for the preschool child m ay include:

N ature of the presenting problem , including chief com plaint

Visual and ocular history

G eneral health history, including prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal history

and review of system s

Fam ily eye and m edical histories

D evelopm ental history of the child.

The collection of dem ographic data generally precedes the taking of the patient

history. H aving the parent(s) or caregiver(s) com plete a questionnaire in advance of

the exam ination facilitates obtaining the patient history.

43

b. Visual Acuity

A n assessm ent of visual acuity usually includes one of the follow ing procedures:

Lea Sym bols chart

Broken W heel acuity cards

H O TV test.

Kay Picture Test

14.

By 3 years of age, m ost children have the necessary behavioral and psychological

developm ent to allow subjective acuity testing. H ow ever, specially designed tests

are still useful to lim it the am ount of verbal interaction needed. The 3-year-old

child can easily m atch sim ple form s and responds w ell to learning through dem on-

stration and im itation of tasks.

95

Visual acuity tests for this age group ideally

involve a m atching task or a forced-choice task, such as pointing to the correct

response.

U se of the Broken W heel acuity cards is appropriate for this age group. Very little

verbal interaction is necessary, and the cards use a Landolt C target, considered the

optim um type of test for visual acuity.

96

This test has the added advantage of

established norm ative values.

97

The Lea Sym bols chart, w hich consists of four optotypes (circle, square, apple,

house), also can be used w ith great success.

98

The child sim ply has to find a

m atching block or point to the shape that m atches the target presented. This m ini-

m izes verbal interaction and m akes the test very useful for children betw een 30

m onths and 5 years. The Lea Sym bols chart is the first pediatric acuity test based

on the logM A R scale, as recom m ended by the N ational Research C ouncil

C om m ittee on Vision.

99

A study of the Lea Sym bols and H O TV charts found that

the tw o w ere com parable in 4- and 5-year-old children, but that in 3-year-olds, the

Lea Sym bols chart had better testability rates.

100

O nly 8 percent of children w ere

untestable w ith the Lea Sym bols chart. A nother study found that alm ost every

child older than 30 m onths could be tested w ith the Lea Sym bols chart.

101

The

H O TV test can also be com pleted by m any preschoolers.

c. Refraction

M easurem ent of refractive error m ay involve:

Static retinoscopy

C ycloplegic retinoscopy.

W ith tw o im portant m odifications, standard static (distance, non-cycloplegic)

retinoscopy can usually be perform ed in preschool children. A m odern video pro-

jection system is a valuable m eans of controlling accom m odation and fixation at 6

m eters. U sing a lens rack or loose lenses and fogging glasses rather than a

phoropter enables the clinician to see the child's face and observe w hen the child

loses fixation at 6 m eters.

C ycloplegic retinoscopy is a valuable procedure for the first evaluation of preschool-

ers and w hen static retinoscopy yields unreliable results or professional judgm ent

indicates otherw ise. This procedure should also be perform ed w hen strabism us or

significant refractive error is present. C yclopentolate (1% ) is the cycloplegic agent

of choice. Tw o drops should be instilled, one at a tim e, 5 m inutes apart, in each

eye.

71

The use of a spray bottle to adm inister the drug is also effective for this age

group. Retinoscopy m ay be perform ed w ith a lens rack or loose lenses 20 30 m in-

utes after instillation.

72

15.

d. Binocular Vision, Accommodation and Ocular Motility

The follow ing procedures are useful for assessing binocular and accom m odative

function:

C over test

Positive and negative fusional vergences (prism bar/step vergence testing)

N ear point of convergence (N PC )

Stereopsis

M onocular estim ation m ethod (M EM ) retinoscopy

Versions.

The cover test is the prim ary m eans of evaluating binocular vision in the preschool

child. It should be perform ed in the prim ary position and, if necessary, in other car-

dinal positions of gaze to screen for noncom itant deviations. W hen a deviation is

present, estim ation of the m agnitude or use of a prism bar enables m ore precise

m easurem ent. The results of the cover test can also be com bined w ith version test-

ing to rule out the presence of a noncom itant deviation.

If the cover test suggests a potentially significant heterophoria or interm ittent stra-

bism us, fusional vergence testing m ay be used to help determ ine w hether treat-

m ent m ay be indicated. Fusional vergence can be assessed objectively, using the

step vergence procedure.

103,104

To assess fusional vergence objectively, the clinician

uses a hand-held prism bar and carefully observes the patient's eyes, looking for a

loss of bifixation as the am ount of prism is gradually increased.

The N PC is an excellent test to use w ith the preschool child because both the break

and recovery m easurem ents can be determ ined objectively. Instead of asking the

child w hen he sees double, the clinician asks the child to keep looking at the target

as it is m oved closer. The clinician carefully observes the child's eyes and deter-

m ines w hen there is a loss of bifixation. The target is then m oved aw ay from the

child until bifixation is regained. U sing this procedure m akes it easy to determ ine

the N PC in a preschool child.

Stereopsis testing can generally be accom plished in preschool children, using com -

m ercially available stereopsis tests. To increase the ability to m easure stereopsis, it

is w ise to use a m atching procedure, in w hich the exam iner constructs a set of fig-

ures that correspond to the figures in the stereopsis test booklet and sim ply asks

the child to point to the picture he or she sees in the test booklet.

O bjective accom m odative testing can be perform ed in preschool children, using

M EM retinoscopy. M EM retinoscopy is easy to perform w ith children of this age

group and provides inform ation about the accom m odative response.

To assess extraocular m uscle function and concom itancy, it is im portant to perform

version testing in all cardinal positions of gaze, using a high-interest fixation target.

W hen a problem is suspected, the cover test procedure can be used in the relevant

position of gaze.

16.

e. Ocular Health Assessment and Systemic Health Screening

A n evaluation of ocular health m ay include:

Evaluation of the ocular anterior segm ent and adnexa

Evaluation of the ocular posterior segm ent

C olor vision testing

A ssessm ent of pupillary responses

Visual field screening (confrontation).

W ith som e m odification, traditional testing used to assess ocular health in adults

can be used in preschool children. M ost preschool children w ill cooperate, allow ing

the use of the biom icroscope to evaluate the anterior segm ent. Pupillary dilation

facilitates thorough evaluation of the posterior segm ent. W ith encouragem ent and

assistance from the parent, to help control fixation, binocular indirect ophthal-

m oscopy is often successful.

C olor vision testing can generally be done w ith standard pseudoisochrom atic

plates. A n alternative is the D 15 colour vision test w hich is often m anageable by

pre-schoolers w hen presented as a m atching/sorting test. O ther alternatives include

the Pease-A llen C olor Test (PA C T), the M r. C olor Test, or C olor Vision M ade Easy,

w hich do not require the child to identify a num ber. A ll of these tests are easy to

adm inister and have high testability rates in preschool children.

105-107

M easurem ent of IO P is not a routine part of the eye and vision exam ination of pre-

school children, but pressure should be assessed w hen ocular signs and sym ptom s

or risk factors for glaucom a exist. H and-held applanation or noncontact tonom e-

ters are available for the m easurem ent of IO P in this population. If it is not possible

to assess IO P reliably under standard clinical conditions, testing under sedation or

anesthesia m ay be appropriate.

C onfrontation visual fields testing should be attem pted w ith preschool children,

w hen indicated, using the techniques described for infants and toddlers. W hen the

results are equivocal or risk factors are present, the clinician should either retest the

child or consult w ith or refer the child to a pediatric ophthalm ologist or neurologist

for appropriate testing.

f. Supplemental Testing

W hen the preschool child's history indicates a possible developm ental lag or a

learning problem , the optom etrist m ay adm inister a developm ental visual perceptu-

al screening test to help diagnose and m anage visual inform ation-processing prob-

lem s. The testing can help assess developm ental level, detect visual perceptual dys-

function, and enable early identification of children at risk for the developm ent of

learning related vision problem s.

17.

The assessm ent of visual perceptual developm ent m ay include:

D enver D evelopm ental Screening Test (D D ST)

D evelopm ental Test of Visual M otor Integration (D TVM I)

Recom m ended for use in this age group,

108

the D D ST w as designed for use w ith

children from birth through 6 years of age. A nother test that can be used for

screening children as young as 3 years is the D TVM I.

109

W hen visual perceptual

problem s are detected, consultation w ith an optom etrist w ho has advanced clinical

training or experience w ith this population should be considered. Referral for con-

sultation w ith the child's pediatrician or other prim ary care physician or a child psy-

chologist or psychiatrist should also be considered w hen problem s in language and

social developm ent are detected.

g. Assessment and Diagnosis

U pon com pleting exam ination of the preschool-age child, the optom etrist assesses

and evaluates the data to establish the diagnosis and to form ulate a m anagem ent

plan. In som e cases, referral for consultation w ith or treatm ent by another

optom etrist, the patient's pediatrician or other prim ary care physician, or another

health care provider m ay be indicated.

C. EXAMINATION OF SCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN

1. General Considerations

This section of the G uideline describes the optom etric exam ination of the school-

age child. The discussion of exam ination com ponents is presented in general term s

and is not intended to be all inclusive. Professional judgm ent and individual patient

history, sym ptom s, findings, and cooperation m ay have significant im pact on the

nature and course of the exam ination.

Som e of the issues relating to infants, toddlers, and preschool children also apply to

this population, particularly children younger than 8 years old. A ge-appropriate

exam ination and m anagem ent strategies should be used. A lthough m ost of the

exam ination procedures used w ith this age group are identical to those recom -

m ended for adults, age-appropriate m odifications of instructions and targets often

m ay be required.

43

2. Early Detection and Prevention

The value of and need for school-based vision screening have been debated for

decades. O ne concern is that the m ajority of school vision screenings test only

visual acuity. Such testing prim arily detects am blyopia and m yopia, and only high

degrees of astigm atism and hyperopia. A lthough detection of such disorders is cer-

tainly a w orthw hile objective, screening for visual acuity alone generally detects

only about 30 percent of children w ho w ould fail a professional eye exam ination.

110

Visual acuity screening often fails to detect those conditions that w ould be expect-

18.

ed to affect learning. Parents or caregivers of children w ho pass vision screening

m ay incorrectly assum e that their children do not require further professional care.

3. Examination Sequence

The pediatric eye and vision exam ination of the school-age child m ay include, but is

not lim ited to, the follow ing (see A ppendices Figure 4):

a. Patient History

A com prehensive patient history for the school-age child m ay include:

N ature of the presenting problem , including chief com plaint

Visual and ocular history

G eneral health history, including prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal history

and review of system s

Fam ily eye and m edical histories

D evelopm ental history of the child

School perform ance history.

The collection of dem ographic data generally precedes taking the patient history.

H aving the parent(s) or caregiver(s) fill out a questionnaire facilitates obtaining the

patient history. Because of the relationship betw een vision and learning, special

attention needs to be paid to the child's school perform ance. W hen a child is not

perform ing up to potential, the optom etrist should probe for signs and sym ptom s

suggestive of a learning related vision problem .

111

* Q uestions can be designed to

define the specific nature of the learning problem and to distinguish disorders of

visual efficiency from a visual perceptual or nonvisual disorder.

112

b. Visual Acuity

Visual acuity m ay be assessed w ith the Snellen acuity chart (m odified for children 6-

8 years of age). A recom m ended m odification is the isolation of one line, or even

one-half line of letters, rather than projection of a full chart.

c. Refraction

M easurem ent of refractive error m ay involve use of the follow ing procedures:

Static (distance) retinoscopy

C ycloplegic retinoscopy

Subjective refraction.

For children over the age of 8, the clinician can usually use traditional assessm ent

procedures to m easure refractive error. For patients below age 8, static (distance)

retinoscopy m ay be perform ed w ithout a phoroptor, using a lens rack or loose lens-

es and fogging glasses. This procedure allow s the practitioner to m ove w ith the

child and to observe w hether the child is fixating properly. C ycloplegic refraction

19.

m ay be necessary in such conditions as strabism us, am blyopia, or significant hyper-

opia.

d. Binocular Vision, Accommodation, and Ocular Motility

Evaluation of binocular and accom m odative function and ocular m otility m ay

include the follow ing procedures:

C over test

N ear point of convergence (N PC )

Positive and negative fusional vergences

A ccom m odative am plitude and facility

M onocular estim ation m ethod (M EM ) retinoscopy

Stereopsis

Versions.

O ther than refractive errors, the m ost prevalent vision conditions in children fall into

the category of accom m odative and binocular vision anom alies.

41

These conditions

m ay interfere w ith school perform ance, causing a num ber of sym ptom s, including

eyestrain, blurred vision, double vision, loss of place, skipped lines, w ord m ovem ent

on the page, inability to sustain attention w hen reading, and decreased reading

com prehension over tim e.

109,113-119

C areful evaluation of these conditions in the

school-age population is critical.

Evaluation of accom m odation and fusional vergence should involve assessm ent of

both the am plitude and the facility of the response. For accom m odation, the eval-

uation m ay include assessm ent of accom m odative am plitude, accom m odative facili-

ty using +2.00/-2.00 D lenses, and accom m odative response using M EM

retinoscopy.

Binocular evaluation should include the cover test and tests of accom m odative con-

vergence/accom m odation (A C /A ) ratio, fusional vergence am plitude w ith either the

Risley prism s or the prism bar, vergence facility, and stereopsis, using a random dot

stereopsis test. A dditionally, negative relative accom m odation (N RA ) and positive

relative accom m odation (PRA ) tests m ay contribute to an understanding of both

accom m odation and binocular status. In analyzing these tests, it is im portant to

exam ine all data and group findings, rather than depending on any one isolated

finding, to arrive at a diagnosis.

120

Versions can be perform ed to rule out a noncom itant deviation. Q ualitative exam i-

nation of eye m ovem ents involves three distinct steps: assessm ent of stability of

fixation, saccadic function, and pursuit function. Subjective techniques involving

observation of the patient's fixation and eye m ovem ents have been developed,

along w ith rating scales, to probe these three areas.

121

20.

e. Ocular Health Assessment and Systemic Health Screening

A n assessm ent of ocular health m ay include:

Evaluation of the ocular anterior segm ent and adnexa

Evaluation of the ocular posterior segm ent

M easurem ent of intraocular pressure

C olor vision testing

A ssessm ent of pupillary responses

Visual field screening (confrontation).

Traditional testing procedures utilized for the evaluation of ocular health in adults

can be used w ith school-age children. M ost w ill cooperate and allow use of the

biom icroscope to evaluate the anterior segm ent and binocular indirect ophthal-

m oscopy to evaluate the posterior segm ent. Pupillary dilation allow s for thorough

evaluation of the posterior segm ent and m ay be repeated as needed at subsequent

visits.

122

The m easurem ent of IO P in school-age children is generally successful w ith either

applanation or noncontact tonom etry. A lthough the prevalence of glaucom a is low

in this population, a baseline m easurem ent at this age is valuable. Tonom etry m ay

be repeated as needed at subsequent visits.

If color vision testing w as not adm inistered w hen a preschool child, it should be

perform ed at this age. A s children enter school, it is helpful to know w hether a

color vision deficiency exists, because severe color vision deficiency m ay cause m is-

labeling of a child as learning disabled.

123

M oreover, color vision deficiency m ay

indicate an ocular health problem .

124

Evaluation of visual fields can be perform ed in school-age children using confronta-

tion visual field screening.

f. Assessment and Diagnosis

U pon com pletion of the exam ination, the optom etrist should assess and evaluate

the data to establish a diagnosis and to form ulate a m anagem ent plan. In som e

cases, referral for consultation w ith or treatm ent by another optom etrist, the

patient's pediatrician or other prim ary care physician, or another health care

provider m ay be indicated.

D. MANAGEMENT OF CHILDREN

1. Patient Education

D iscussion and com m unication w ith the parents or caregivers and the child should

occur at the end of the eye exam ination to review test findings. The optom etrist's

prim ary responsibility in this area is educating parents or caregivers about any eye

or vision disorders and vision care. M any parents and caregivers believe the screen-

21.

ing perform ed by the child's pediatrician or other prim ary care physician or school

nurse is sufficient to rule out all significant visual disorders. H ow ever, these screen-

ings are lim ited and w ere not intended to replace a com prehensive eye exam ination

The im portance of adhering to an eye and vision exam ination schedule should be

em phasized from a preventive standpoint as w ell. Early detection and preventive

care can help avoid, or m inim ize, the consequences of disorders such as am blyopia

and strabism us.

The optom etrist can also play an im portant role by educating parents/caregivers

and children about eye safety, particularly regarding sports-related eye safety.

Sports and recreational activities accounted for nearly 40,000 of the eye injuries

reported in 1991. Baseball injuries w ere the m ost frequent cause of eye injuries

am ong children 5-14 years of age.

125

A spectacle lens m aterial equivalent or supe-

rior in im pact resistance to that of 2m m polycarbonate or trivex is recom m ended

for use w ith children, except w hen such lenses w ill not fulfill the visual require-

m ents of the patient. For those cases in w hich protective lens m aterials are not

used, the optom etrist should obtain inform ed consent from parents and/or care-

givers.

O ptom etrists should educate parents or caregivers about the im portance of early,

preventive eye care, including exam inations at the age of 6 m onths, at age 3,

before entering first grade, and periodically during the school years. The extent to

w hich a child is at risk for the developm ent of eye and vision problem s determ ines

the appropriate re-evaluation schedule. Individuals w ith ocular signs and sym ptom s

require prom pt exam ination. Furtherm ore, the presence of certain risk factors m ay

necessitate m ore frequent exam inations, based on professional judgm ent (see Table

3).

Patient Age Asymptomatic / risk-

free

At-risk

Birth to 24 m onths A t 6 m onths of age A t 6 m onths of age

or as recom m ended

2 to 5 years A t 3 years of age A t 3 years of age or

as recom m ended

6 to 18 years Before first grade and

every 2 years thereafter

A nnually or as recom -

m ended

Recommended Eye Examiniation Frequency for the Pediatric Patient

Table 3

22.

2. Coordination, Frequency, and Extent of Care

The developing visual system is considered m ost susceptible to interference during

the first few years of life.

51,126-128

In the child of 6 m onths, vision has assum ed the

position of dom inant sense, and it w ill form the basis of later perceptual, cognitive,

and social developm ent.

129

M oreover, in the child of this age, vision has rapidly

developed in m ost crucial areas, including visual acuity, accom m odation, and stere-

opsis.

11-17

Interference during this critical phase of developm ent m ay be deleteri-

ous. For instance, abnorm alities present at birth and shortly thereafter, including

opacities of the ocular m edia (e.g., congenital cataract) and early-onset strabism us,

m ay have profound effects on the developing visual system . Thus, the efforts of

the child's pediatrician or other prim ary care physician are vital in the detection of

ocular abnorm alities that m ay require referral for an eye exam ination and treat-

m ent.

The child's first eye and vision exam ination should be scheduled at 6 m onths of age

(or sooner if signs or sym ptom s w arrant). W hen no abnorm alities are detected at

this age, the next exam ination should be scheduled at age 3.

The child considered at risk for the developm ent of eye and vision problem s m ay

need additional testing or m ore frequent re-evaluation. Factors placing an infant,

toddler, or child at significant risk for visual im pairm ent include:

Prem aturity, low birth w eight, prolonged supplem ental oxygen, or grade III

or IV intraventricular hem orrhage

Fam ily history of retinoblastom a, congenital cataracts, or m etabolic or

genetic disease

Infection of m other during pregnancy (e.g., rubella, toxoplasm osis, venere

al disease, herpes, cytom egalovirus, or hum an im m unodeficiency virus)

D ifficult or assisted labor, w hich m ay be associated w ith fetal distress or

low A pgar scores

H igh refractive error

Strabism us

A nisom etropia

Know n or suspected central nervous system dysfunction evidenced by

developm ental delay, cerebral palsy, dysm orphic features, seizures, or

hydrocephalus.

A n estim ated 17-25 percent of school-age children have vision problem s,

10

m any of

w hich m ay interfere w ith the children's abilities to reach their potential in school. It

is clear that all school-age children should have com prehensive eye and vision

exam inations, before entering the first grade and periodically thereafter. Som e chil-

dren m ay require m ore frequent care, depending on the nature of any diagnosed

eye or vision disorder.

23.

IV. CONCLUSION

C hildren account for a large percentage of the population of C anada. Studies have

dem onstrated that the prevalence of eye and vision disorders is substantial in this

group. Research also indicates that early detection and intervention are particularly

im portant in children because of the rapid developm ent of the visual system in

early childhood and its sensitivity to interference. W hen disorders such as am bly-

opia and strabism us are undetected, the long-term consequences can be serious in

term s of quality of life, com fort, appearance, and career opportunities. In addition,

the cost of providing appropriate treatm ent for longstanding eye and vision disor-

ders m ay be significantly higher than the cost of detecting and treating these prob-

lem s early in life.

25.

V. REFEREN C ES

1. W yngaarden JB. M edicine as a public service. In: W yngaarden JB, Sm ith LH , eds. C ecil's textbook

of m edicine, 18th ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1988:7-8.

2. C atania LJ. Prim ary care. In: N ew com b RD , M arshall EC , eds. Public health and com m unity optom -

etry, 2nd ed. Boston: Butterw orths, 1990:295-310.

3. Statistics C anada. Population C ensus 2003, http://w w w .statcan.ca.

4. G erali P, Flom M C , Raab EL. Report of C hildren's Screening Task Force. Schaum burg, IL: N ational

Society to Prevent Blindness, 1990.

5. Poe G S. Eye care visits and use of eyeglasses or contact lenses. U nited States 1979 and 1980. Vital

and health statistics. Series 10, N o. 145, D H H S Publication (PH S) 84 1573, H yattsville, M D : N ational

C enter for H ealth Statistics, 1984.

6. Pizzarello L, Tilp M , Tiezzi L, et al. A new school-based program to provide glasses: C hildsight. J

A A PO S 1998; 6:372-4.

7. W asserm an RC , C roft C A , Brotherton SE. Preschool vision screening in pediatric practice: a study

from the Pediatric Research in O ffice Setting (PRO S) N etw ork. A m erican A cadem y of Pediatrics.

Pediatrics 1992; 89:834-8.

8. A m erican Public H ealth A ssociation. Im proving early childhood eyecare. Policy Statem ent N o. 20011.

W ashington, D C : A PH A , 2001.

9. A m erican Foundation for Vision Aw areness. C hildren's vision and literacy cam paign position paper.

St. Louis, M O : A FVA , 1993.

10. G rounds. A . Pediatric Eye C are. Blackw ell Science. O xford. 1995

11. D obson V, Teller D Y. Visual acuity in hum an infants: a review and com parison of behavioral and

electrophysiological studies. Vision Res 1978; 17:1469-83.

12. G w iazda J, Brill S, M ohindra I, H eld R. Preferential looking acuity in infants from tw o to fifty-eight

w eeks of age. A m J O ptom Physiol O pt 1980; 57:428-32.

13. Banks M S. The developm ent of visual accom m odation during early infancy. C hild D ev 1980;

51:646-66.

14. Brookm an KE. O cular accom m odation in hum an infants. A m J O ptom Physiol O pt 1983; 60:91-9.

15. Banks M S, A slin RN , Letson RD . Sensitive period for the developm ent of hum an binocular vision.

Science 1975; 190:675-7.

16. H ohm an A , C reutzfeldt O D . Squint and the developm ent of binocularity in hum ans. N ature 1975;

254:613-4.

17. C iner EB, Scheim an M M , Schanel-Klitsch E, W eil L. Stereopsis testing in 18- to 35- m onth-old chil-

dren using operant preferential looking. O ptom Vis Sci 1989; 66:782-7.

18. W iesel T, H ubel D . Effects of visual deprivation of m orphology and physiology of cells in the cat's

lateral geniculate body. J N europhysiol 1963; 26:578-85.

19. W iesel T, H ubel D . Single cell response in striate cortex of kittens deprived of vision in one eye. J

N europhysiol 1963; 26:1003-17.

20. M ohindra I, Jacobson SG , Thom as J, H eld R. D evelopm ent of am blyopia in infants. Trans

O phthalm ol Soc U K 1979; 99:344-6.

21. Epelbaum M , M illeret C , Buisseret P, D ufier JL. The sensitive period for strabism ic am blyopia in

hum ans. O phthalm ology 1993; 100:323-7.

22. A ngi M R, Pucci V, Forattini F, Form entin PA . Results of photorefractom etric screening for am blyo-

genic defects in children aged 20 m onths. Behav Brain Res 1992; 49(1):91 7.

23. N eum ann E, Freidm an Z, A bel-Peleg B. Prevention of strabism ic am blyopia of early onset w ith spe-

cial reference to the optim al age for screening. J Pediatr O phthalm ol Strabism us 1987; 24:106-10.

24. Eibschitz-Tsim honi M , Friedm an T, N aor J, et al. Early screening for am blyogenic risk factors low ers

the prevalence and severity of am blyopia. J A A PO S 2000; 4:194-9.

26.

25. Birch EE, H ale LA . O perant assessm ent of stereoacuity. C lin Vis Sci 1989; 4:295-300.

26. H ow land H C , A tkinson J, Braddick O , French J. Infant astigm atism m easured by photorefraction.

Science 1978; 202:331-3.

27. Fulton A B, D obson V, Salem D , et al. C ycloplegic refractions of infants and young children. A m J

O phthalm ol 1980; 90:239-47.

28. M ohindra I, H eld R. Refraction in hum ans from birth to five years. D oc O phthalm ol Proc 1981;

series 28:19-27.

29. H ow land H C , Sayles N . Photorefractive m easurem ents of astigm atism in infants and young children.

Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1984; 25:93-102.

30. M ohindra I. A technique for infant vision exam ination. A m J O ptom Physiol O pt 1975; 52:867-70.

31. Tongue A C , C ibis G W . Brckner test. O phthalm ology 1981; 88:1041-4.

32. G w iazda J, W olfe JM , Brill S, et al. Q uick assessm ent of preferential looking acuity in infants. A m J

O ptom Physiol O pt 1980; 57:420-7.

33. M cD onald M , D obson V, Sebris SL, et al. The acuity card procedure: a rapid test of infant acuity.

Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1985; 26:1158-62.

34. Birch E, W illiam s C , H unter J, Lapa M C , and the A LSPA C "C hildren in Focus" Study Team . Random

dot stereoacuity of preschool children. J Pediatr O phthalm ol Strabism us 1997; 34:217-22.

35. C iner EB, Schanel-Klitsch E, H erzberg C . Stereoacuity developm ent. 6 m onths to 5 years. A new

tool for testing and screening. O ptom Vis Sci 1996; 73:43-8.

36. O rel-Bixler D , Brodie A . Vision screening of infants and toddlers: photorefraction and stereoacuity.

Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1995; 36(suppl):868.

37. A m erican O ptom etric A ssociation. Position paper: Recom m endations for regular optom etric care.

St. Louis, M O : A O A , 1994.

38. Roberts J. Eye exam ination findings am ong children, U nited States. Vital and health statistics, series

11, no. 115, D H EW publication (H SM ) 72-1057, H yattsville, M D : N ational C enter for H ealth Statistics,

1972.

39. Roberts J. Eye exam ination findings am ong children aged 12-17, U nited States. Vital and health

statistics, series 11, no. 155, D H EW publication (H RA ) 76-1637, H yattsville, M D : N ational C enter for

H ealth Statistics, 1975.

40. C iner EB, Schm idt PP, O rel-Bixler D , et al. Vision screening of preschool children: Evaluating the

past, looking tow ard the future. O ptom Vis Sci. 1998; 75:571 84.

41. Scheim an M , G allaw ay M , C oulter R, et al. Prevalence of vision and ocular disease conditions in a

clinical pediatric population. J A m O ptom A ssoc 1996; 67:193-202.

42. Rosner J, Rosner J. Pediatric optom etry, 2nd ed. Boston: Butterw orths, 1990:47-71.

43. Rouse M W , Ryan JM . The optom etric exam ination and m anagem ent of children. In: Rosenbloom

A A , M organ M W , eds. Principles and practice of pediatric optom etry. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott,

1990:155-91.

44. Press LJ, M oore BD . C linical pediatric optom etry. Boston: Butterw orth-H einem ann, 1993:25-80.

45. W hite BL. The first three years of life. Englew ood C liffs, N J: Prentice-H all, Inc., 1975:77-102.

46. C am pbell LR, C harney E. Factors associated w ith delay in diagnosis of childhood am blyopia.

Pediatrics 1991; 87:178-85.

47. H ow land H , H ow land B. Photorefraction: a technique for study of refractive error at a distance. J

O pt Soc A m 1974; 64:240-9.

48. A tkinson J, Braddick O . The use of isotropic photorefraction for vision screening in infants. A cta

O phthalm ol 1983; 157(suppl):36-45.

49. D uckm an R. U sing photorefraction to evaluate refractive error, ocular alignm ent, and accom m oda-

tion in infants, toddlers, and m ultiple handicapped children. Probl O ptom 1990; 2(3):333-53.

50. Preslan M W , Zim m erm an E. Photorefraction screening in prem ature infants. O phthalm ology 1993;

100:762-8.

27.

51. W right KW , Edelm an PM , W alonker F, Yiu S. Reliability of fixation preference testing in diagnosing

am blyopia. A rch O phthalm ol 1986; 104:549-53.

52. W right KW , W alonker F, Edelm an P. 10-D iopter fixation test for am blyopia. A rch O phthalm ol 1981;

99:1242-6.

53. W hittaker KW , O 'Flynn E, M anners RM . D iagnosis of am blyopia using the 10-diopter fixation test:

a proposed m odification for patients w ith unilateral ptosis. J Pediatr O phthalm ol Strabism us 2000;

37:21-3.

54. Law s D , N oonan C P, W ard A , C handna A . Binocular fixation pattern and visual acuity in children

w ith strabism ic am blyopia. J Pediatr O phthalm ol Strabism us 2000; 37(1):24-8.

55. Birch EE, Stager D R, Berry P, Everett M E. Prospective assessm ent of acuity and stereopsis in am bly-

opic infantile esotropes follow ing early surgery. Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1990; 31:758-65.

56. W ilcox LM Jr, Sokol S. C hanges in binocular fixation patterns and the visually evoked potential in

the treatm ent of esotropia w ith am blyopia. O phthalm ology 1980; 87:1273 81.

57. M ayer D L, Fulton A B, H ansen RM . Preferential looking acuity obtained w ith a staircase procedure in

pediatric patients. Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1982; 23:538-43.

58. Birch EE, N aegele J, Bauer JA , H eld R. Visual acuity of toddlers. Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1980;

20(suppl):210.

59. Spierer A , Royzm an Z, C hetrit A , et al. Vision screening of preverbal children w ith Teller acuity cards.

O phthalm ology 1999; 106:849-54.

60. Birch EE, Stager D R. M onocular acuity and stereopsis in infantile esotropia. Invest O phthalm ol Vis

Sci 1985; 26:1624-30.

61. M ohn G , van H of-van D uin J, Fetter W PF, et al. A cuity assessm ent of non-verbal infants and chil-

dren: clinical experience w ith the acuity card procedure. D ev M ed C hild N eurol 1988; 30(suppl):232-

44.

62. Stager D R, Birch EE. Preferential-looking acuity and stereopsis in infantile esotropia. J Pediatr

O phthalm ol Strabism us 1986; 23:160-5.

63. M ayer D L, Fulton A B, Rodier D . G rating and recognition acuities of pediatric patients.

O phthalm ology 1984; 91:947-53.

64. M ayer D L. A cuity of am blyopic children for sm all field gratings and recognition stim uli. Invest

O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1986; 27:1148-53.

65. Ellis G S Jr., H artm ann EE, Love A , et al. Teller acuity cards versus clinical judgm ent in the diagnosis

of am blyopia w ith strabism us. O phthalm ology 1988; 95:788-91.

66. Sokol S, M oskow itz A . C om parison of pattern VEPs and preferential-looking behavior in 3-m onth-

old infants. Invest O phthalm ol Vis Sci 1985; 26:359-65.

67. Riddell PM , Ladenheim B, M ast J, et al. C om parison of visual acuity in infants: Teller acuity cards

and sw eep visual evoked potentials. O ptom Vis Sci 1997; 74:702-7.

68. Prager TC , Zou YL, Jensen C L, et al. Evaluation of m ethods for assessing visual function of infants.

J A A PO S 1999; 3:275-82.