Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stylistics

Uploaded by

John Perseus LeeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stylistics

Uploaded by

John Perseus LeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Stylistics is the study and interpretation of texts in regard to their linguistic and tonal style.

As a

discipline, it links literary criticism tolinguistics. It does not function as an autonomous domain on its

own, but it can be applied to an understanding of literature and journalismas well

as linguistics.

[1][2]

Sources of study in stylistics may range from canonical works of writing to popular

texts, and from advertising copy to news, non-fiction, and popular culture, as well as

to political and religious discourse.

[3]

Stylistics as a conceptual discipline may attempt to establish principles capable of explaining

particular choices made by individuals and social groups in their use of language, such as in the

literary production and reception of genre, the study of folk art, in the study of

spokendialects and registers, and can be applied to areas such as discourse analysis as well

as literary criticism.

Common features of style include the use of dialogue, including regional accents and

individual dialects (or ideolects), the use of grammar, such as the observation of active

voice and passive voice, the distribution of sentence lengths, the use of particular language

registers, and so on. In addition, stylistics is a distinctive term that may be used to determine the

connections between the form and effects within a particular variety of language. Therefore, stylistics

looks at what is 'going on' within the language; what the linguistic associations are that the style of

language reveals.

Early twentieth century[edit]

The analysis of literary style goes back to the study of classical rhetoric, though modern stylistics

has its roots in Russian Formalism

[4]

and the related Prague School of the early twentieth century.

In 1909, Charles Bally's Trait de stylistique franaise had proposed stylistics as a distinct academic

discipline to complement Saussureanlinguistics. For Bally, Saussure's linguistics by itself couldn't

fully describe the language of personal expression.

[5]

Bally's programme fitted well with the aims of

the Prague School.

[6]

Taking forward the ideas of the Russian Formalists, the Prague School built on the concept

of foregrounding, where it is assumed that poetic language is considered to stand apart from non-

literary background language, by means of deviation (from the norms of everyday language)

or parallelism.

[7]

According to the Prague School, however, this background language isn't constant,

and the relationship between poetic and everyday language is therefore always shifting.

[8]

Late twentieth century[edit]

Roman Jakobson had been an active member of the Russian Formalists and the Prague School,

before emigrating to America in the 1940s. He brought together Russian Formalism and

American New Criticism in his Closing Statement at a conference on stylistics at Indiana

University in 1958.

[9]

Published as Linguistics and Poetics in 1960, Jakobson's lecture is often

credited with being the first coherent formulation of stylistics, and his argument was that the study of

poetic language should be a sub-branch of linguistics.

[10]

The poetic function was one of six

general functions of language he described in the lecture.

Michael Halliday is an important figure in the development of British stylistics.

[11]

His 1971

study Linguistic Function and Literary Style: An Inquiry into the Language of William Golding's The

Inheritors is a key essay.

[12]

One of Halliday's contributions has been the use of the term register to

explain the connections between language and its context.

[13]

For Halliday register is distinct

from dialect. Dialect refers to the habitual language of a particular user in a specific geographical or

social context. Register describes the choices made by the user,

[14]

choices which depend on three

variables: field ("what the participants... are actually engaged in doing", for instance, discussing a

specific subject or topic),

[15]

tenor (who is taking part in the exchange) and mode (the use to which

the language is being put).

Fowler comments that different fields produce different language, most obviously at the level

of vocabulary (Fowler. 1996, 192) The linguist David Crystal points out that Halliday's 'tenor' stands

as a roughly equivalent term for style, which is a more specific alternative used by linguists to avoid

ambiguity. (Crystal. 1985, 292) Hallidays third category, mode, is what he refers to as the symbolic

organisation of the situation. Downes recognises two distinct aspects within the category of mode

and suggests that not only does it describe the relation to the medium: written, spoken, and so on,

but also describes the genre of the text. (Downes. 1998, 316) Halliday refers to genre as pre-coded

language, language that has not simply been used before, but that predetermines the selection of

textual meanings. The linguist William Downes makes the point that the principal characteristic of

register, no matter how peculiar or diverse, is that it is obvious and immediately recognisable.

(Downes. 1998, 309)

Literary stylistics[edit]

In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, Crystal observes that, in practice, most stylistic

analysis has attempted to deal with the complex and valued language within literature, i.e. literary

stylistics. He goes on to say that in such examination the scope is sometimes narrowed to

concentrate on the more striking features of literary language, for instance, its deviant and

abnormal features, rather than the broader structures that are found in whole texts or discourses.

For example, the compact language of poetry is more likely to reveal the secrets of its construction

to the stylistician than is the language of plays and novels. (Crystal. 1987, 71).

Poetry[edit]

As well as conventional styles of language there are the unconventional the most obvious of which

is poetry. In Practical Stylistics, HG Widdowson examines the traditional form of the epitaph, as

found on headstones in a cemetery. For example:

His memory is dear today

As in the hour he passed away.

(Ernest C. Draper Ern. Died 4.1.38)

(Widdowson. 1992, 6)

Widdowson makes the point that such sentiments are usually not very interesting

and suggests that they may even be dismissed as crude verbal carvings and crude

verbal disturbance (Widdowson, 3). Nevertheless, Widdowson recognises that they

are a very real attempt to convey feelings of human loss and preserve affectionate

recollections of a beloved friend or family member. However, what may be seen as

poetic in this language is not so much in the formulaic phraseology but in where it

appears. The verse may be given undue reverence precisely because of the

sombre situation in which it is placed. Widdowson suggests that, unlike words set in

stone in a graveyard, poetry is unorthodox language that vibrates with inter-textual

implications. (Widdowson. 1992, 4)

Two problems with a stylistic analysis of poetry are noted by PM Wetherill in Literary

Text: An Examination of Critical Methods. The first is that there may be an over-

preoccupation with one particular feature that may well minimise the significance of

others that are equally important. (Wetherill. 1974, 133) The second is that any

attempt to see a text as simply a collection of stylistic elements will tend to ignore

other ways whereby meaning is produced. (Wetherill. 1974, 133)

Implicature[edit]

In Poetic Effects from Literary Pragmatics, the linguist Adrian Pilkington analyses

the idea of implicature, as instigated in the previous work of Dan

Sperber and Deirdre Wilson. Implicature may be divided into two categories: strong

and weak implicature, yet between the two extremes there are a variety of other

alternatives. The strongest implicature is what is emphatically implied by the

speaker or writer, while weaker implicatures are the wider possibilities of meaning

that the hearer or reader may conclude.

Pilkingtons poetic effects, as he terms the concept, are those that achieve most

relevance through a wide array of weak implicatures and not those meanings that

are simply read in by the hearer or reader. Yet the distinguishing instant at which

weak implicatures and the hearer or readers conjecture of meaning diverge

remains highly subjective. As Pilkington says: there is no clear cut-off point

between assumptions which the speaker certainly endorses and assumptions

derived purely on the hearers responsibility. (Pilkington. 1991, 53) In addition, the

stylistic qualities of poetry can be seen as an accompaniment to Pilkingtons poetic

effects in understanding a poem's meaning.

Tense[edit]

Widdowson points out that in Samuel Taylor Coleridges poem "The Rime of the

Ancient Mariner" (1798), the mystery of the Mariners abrupt appearance is

sustained by an idiosyncratic use of tense. (Widdowson. 1992, 40) For instance, the

Mariner holds the wedding-guest with his skinny hand in the present tense, but

releases it in the past tense('...his hands dropt he.'); only to hold him again, this time

with his glittering eye, in the present. (Widdowson. 1992, 41)

The point of poetry[edit]

Widdowson notices that when the content of poetry is summarised, it often refers to

very general and unimpressive observations, such as nature is beautiful; love is

great; life is lonely; time passes, and so on. (Widdowson. 1992, 9) But to say:

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end ...

William Shakespeare, 60.

Or, indeed:

Love, all alike, no season knows nor clime,

Nor hours, days months, which are the rags of time ...

John Donne, The Sun Rising, Poems (1633)

This language gives the reader a new perspective on

familiar themes and allows us to look at them without the

personal or social conditioning that we unconsciously

associate with them. (Widdowson. 1992, 9) So, although

the reader may still use the same exhausted words and

vague terms like love, heart and soul to refer to human

experience, to place these words in a new and refreshing

context allows the poet the ability to represent humanity

and communicate honestly. This, in part, is stylistics, and

this, according to Widdowson, is the point of poetry

(Widdowson. 1992, 76).

You might also like

- The Book of Literary Terms: The Genres of Fiction, Drama, Nonfiction, Literary Criticism, and Scholarship, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Book of Literary Terms: The Genres of Fiction, Drama, Nonfiction, Literary Criticism, and Scholarship, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Stylistics: Early Twentieth CenturyDocument4 pagesStylistics: Early Twentieth CenturyAnonymous 2bT3lnNY1ZNo ratings yet

- Stylistics - WikipediaDocument10 pagesStylistics - WikipediaGarba MusaNo ratings yet

- StylisticsDocument11 pagesStylisticsdearbhupi100% (1)

- STYLISTICS Material For Introduction To Linguistic ClassDocument8 pagesSTYLISTICS Material For Introduction To Linguistic ClassRochelle PrieteNo ratings yet

- Stylistics Analysis of The Poem To A Skylark' by P.B.ShelleyDocument14 pagesStylistics Analysis of The Poem To A Skylark' by P.B.ShelleyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)50% (2)

- Document 16Document12 pagesDocument 16Anichka VardanyanNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Style PDF 4Document4 pagesApproaches To Style PDF 4english botanyNo ratings yet

- Style and StylisticsDocument7 pagesStyle and Stylisticsمحمد جمشید100% (3)

- Style ImpDocument13 pagesStyle ImpZaheer AhmadNo ratings yet

- Stylistics and PoetryDocument37 pagesStylistics and PoetryKhalid Shamkhi75% (4)

- Discourse AnalysisDocument97 pagesDiscourse AnalysisKiran Abbas KiranNo ratings yet

- Stylistics Retrospect and ProspectDocument12 pagesStylistics Retrospect and ProspectKhalidNo ratings yet

- Topics: I. What Is Style? Explain Its Traditional, Modern and Linguistic Concepts. II. What Is Stylistics?Document4 pagesTopics: I. What Is Style? Explain Its Traditional, Modern and Linguistic Concepts. II. What Is Stylistics?Faisal SharifNo ratings yet

- Stylistics Analysis of The Poem To A Skylark' by P.B.ShelleyDocument14 pagesStylistics Analysis of The Poem To A Skylark' by P.B.ShelleyHamayun Khan100% (1)

- Manifesto 1Document12 pagesManifesto 1Nancy HenakuNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 in StylisticsDocument21 pagesLecture 2 in Stylisticsmehdaoui amariaNo ratings yet

- Stylistics and Linguistic Analyses of Literary Works: Received: 17-01-2019 Accepted: 31-01-2019 Published: 28-02-2019Document6 pagesStylistics and Linguistic Analyses of Literary Works: Received: 17-01-2019 Accepted: 31-01-2019 Published: 28-02-2019Nancy Megawati SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Leda and The Swan PDFDocument9 pagesLeda and The Swan PDFIonela Loredana BatogNo ratings yet

- The Abc of Stylistics: A Preliminary Investigation: Dr. Muhammad Aminu ModeDocument5 pagesThe Abc of Stylistics: A Preliminary Investigation: Dr. Muhammad Aminu ModeBakhita MaryamNo ratings yet

- Style and Stylistics: A Breeding Ground For AmbiguityDocument20 pagesStyle and Stylistics: A Breeding Ground For AmbiguityDiana SahleanuNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Ii Review of LiteratureDocument52 pagesChapter - Ii Review of LiteratureMohammad ShoebNo ratings yet

- Stylitics IntroDocument34 pagesStylitics IntroSami ktkNo ratings yet

- STYLISTICS, Russian FormalismDocument2 pagesSTYLISTICS, Russian FormalismAnju Susan Koshy BEnglMalNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two AdeDocument20 pagesChapter Two AdeElijah AladeNo ratings yet

- Style and Stylistics What Is StyleDocument6 pagesStyle and Stylistics What Is StyleRochelle Priete100% (1)

- Curs StilisticaDocument75 pagesCurs StilisticaMadalina VasileNo ratings yet

- Paper 13Document11 pagesPaper 13vk9115250No ratings yet

- Stylistics and StructuralismDocument23 pagesStylistics and StructuralismMahfoodh AljubouryNo ratings yet

- Literature AssignmentDocument6 pagesLiterature AssignmentRisma AjaNo ratings yet

- Jakobson, Linguistics and PoeticsDocument8 pagesJakobson, Linguistics and PoeticsAlyssa DizonNo ratings yet

- Oral NarrativeDocument12 pagesOral Narrativestirlitz gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Through The Maze of StyleDocument15 pagesThrough The Maze of StylePatryk GmurkowskiNo ratings yet

- The Concepts of Style and StylisticsDocument9 pagesThe Concepts of Style and StylisticsZaheer AhmadNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Style and Content: 3.0 ObjectivesDocument10 pagesUnit 3 Style and Content: 3.0 ObjectivesAnonymous 9hu7flNo ratings yet

- Dolls House FosDocument11 pagesDolls House FosaaravNo ratings yet

- RZ349 Jki 97Document9 pagesRZ349 Jki 97Kehinde AdeniyiNo ratings yet

- A Stylistic Analysis of William Henry Davies' LeisureDocument7 pagesA Stylistic Analysis of William Henry Davies' LeisureAbdur RehmanNo ratings yet

- The Linguistic Notion of StyleDocument3 pagesThe Linguistic Notion of StyleRica J'n BarroquilloNo ratings yet

- 3 History of StylisticsDocument8 pages3 History of StylisticsAwais Tareq50% (2)

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris FikriDocument9 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris FikriFikri ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- History of StylisticDocument1 pageHistory of StylisticStefanie Rose Domingo0% (1)

- 6 Major Concepts of StylisticsDocument12 pages6 Major Concepts of StylisticsAwais TareqNo ratings yet

- EE Cummings Huminity I Love You. Assignment 2Document8 pagesEE Cummings Huminity I Love You. Assignment 2KB BalochNo ratings yet

- LiteratureDocument9 pagesLiteratureJudithNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Analysis of Ted Hughes' Poem: "The Casualty": Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL)Document8 pagesStylistic Analysis of Ted Hughes' Poem: "The Casualty": Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL)Sarang KhanNo ratings yet

- A Stylistic Analysis of The Figurative Language Style Found in "A Tale of Two Cities" by Charles DickensDocument22 pagesA Stylistic Analysis of The Figurative Language Style Found in "A Tale of Two Cities" by Charles Dickensshamsherwalikhan khanNo ratings yet

- اسلوبیاتDocument6 pagesاسلوبیاتzeb345No ratings yet

- 12.raj Kumar A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF W.H.AUDENS POEM THE SHIELD OF ACHILLESDocument14 pages12.raj Kumar A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF W.H.AUDENS POEM THE SHIELD OF ACHILLESCandy FlossNo ratings yet

- Intro To Stylistics (Lec 1)Document13 pagesIntro To Stylistics (Lec 1)Henz QuintosNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Language of Poetry Through Deviation: Md. Nurul HaqueDocument8 pagesExploring The Language of Poetry Through Deviation: Md. Nurul HaqueTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Literary Stylistics: An Overview of Its Evolution: Moazzam Ali Malik Assistant Professor University of GujratDocument28 pagesLiterary Stylistics: An Overview of Its Evolution: Moazzam Ali Malik Assistant Professor University of GujratAdejokeNo ratings yet

- 1479963576-11 - IJHAMS - Language As A Marker of Social Status in Shaw's PygmalionDocument6 pages1479963576-11 - IJHAMS - Language As A Marker of Social Status in Shaw's PygmalionManav JhaveriNo ratings yet

- Stylistics .Script LanguageDocument11 pagesStylistics .Script LanguagekhanNo ratings yet

- Lodge, David - Modern Criticism and Theory (1) - RemovedDocument89 pagesLodge, David - Modern Criticism and Theory (1) - Removedbharathivarshini05No ratings yet

- Towards A Cultural Approach To StylisticDocument18 pagesTowards A Cultural Approach To StylisticLourdes ArguellesNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Stylistics and The LiterarDocument8 pagesApproaches To Stylistics and The LiterarsilviaNo ratings yet

- Rhetoric SystemDocument40 pagesRhetoric SystemMushkey AlaNo ratings yet

- Pars Pro Toto: LiteratureDocument3 pagesPars Pro Toto: LiteratureDe Jesus Paola KristinaNo ratings yet

- Cultural Issues in TranslationDocument5 pagesCultural Issues in TranslationJovana Vunjak0% (1)

- HypothesisDocument30 pagesHypothesisShashikumar TheenathayaparanNo ratings yet

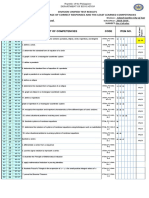

- Practical Research DLL Week 2Document5 pagesPractical Research DLL Week 2John Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- How To PROGRAMDocument1 pageHow To PROGRAMJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Humanities QuesDocument1 pageHumanities QuesJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- DLP TRENDS Q2 Week 2 - Participatory and Representative DemocracyDocument7 pagesDLP TRENDS Q2 Week 2 - Participatory and Representative DemocracyMaria Victoria PadroNo ratings yet

- BitterDocument1 pageBitterJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- How To Put On and Remove A Face MaskDocument2 pagesHow To Put On and Remove A Face MaskJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- How To Kill Snakes Around The HouseDocument3 pagesHow To Kill Snakes Around The HouseJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Sampling QuizDocument1 pageSampling QuizJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- 1st SHSDocument60 pages1st SHSJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Nature of LawDocument31 pagesNature of LawJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Core Principles of Business EthicsDocument10 pagesCore Principles of Business EthicsJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Debateee TopicsDocument18 pagesDebateee TopicsJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Ethical and Social Responsibility - 0Document8 pagesLesson Plan Ethical and Social Responsibility - 0nicodemus balasuelaNo ratings yet

- Nature of LawDocument31 pagesNature of LawJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics1Document1 pageBusiness Ethics1John Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics1Document1 pageBusiness Ethics1John Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Parental ConsentDocument1 pageParental ConsentJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- TrendsDocument3 pagesTrendsJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- ManifestoDocument4 pagesManifestoJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Active Listening SkillsDocument7 pagesActive Listening SkillsDeepika RaghuramanNo ratings yet

- 1stQ Week2Document4 pages1stQ Week2Jayram JavierNo ratings yet

- Theoritical FrameworkDocument6 pagesTheoritical FrameworkJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Decongested Fourth Quarter Competencies Grade Ten EnglishDocument5 pagesDecongested Fourth Quarter Competencies Grade Ten EnglishJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- 7 Basics To Serving Wine and GlasswareDocument3 pages7 Basics To Serving Wine and GlasswareJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- What Job Do You LikeDocument24 pagesWhat Job Do You LikeJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Guide: Instructional PlanningDocument6 pagesCurriculum Guide: Instructional PlanningJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Band 7+Document15 pagesVocabulary Band 7+John Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Some Animals: Objective: After The Lesson, The Kids Will Be Able To Recognize Cat, Dog, and TurtleDocument18 pagesSome Animals: Objective: After The Lesson, The Kids Will Be Able To Recognize Cat, Dog, and TurtleJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Food and Beverage ServicesDocument1 pageFood and Beverage ServicesJohn Perseus LeeNo ratings yet

- Moves and Acts Essay Unit 2Document6 pagesMoves and Acts Essay Unit 2José Saúl Barajas VillegasNo ratings yet

- Levi Strauss, Savage MindDocument22 pagesLevi Strauss, Savage MindLee ColonNo ratings yet

- Casual Communicative StyleDocument2 pagesCasual Communicative StyleReychel NecorNo ratings yet

- LanguagesDocument18 pagesLanguagesukasha khalidNo ratings yet

- Tsl3104 Course Work AssessmentDocument10 pagesTsl3104 Course Work AssessmentNoorkamaliah KamaliahNo ratings yet

- Galáthach HathevíuDocument61 pagesGaláthach HathevíuLuisReytecNo ratings yet

- Seven Barriers To Great CommunicationDocument4 pagesSeven Barriers To Great CommunicationShafiq Khan100% (3)

- HW5e Beginner Test Unit 5BDocument2 pagesHW5e Beginner Test Unit 5BAndric JavorkaNo ratings yet

- Seed Sort Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesSeed Sort Lesson Planapi-282834570No ratings yet

- Theme-Based TeachingDocument29 pagesTheme-Based TeachingSare BaykalNo ratings yet

- English Lexicology (Reader) PDFDocument145 pagesEnglish Lexicology (Reader) PDFVũ Tuấn AnhNo ratings yet

- Ramma Clauses: Group 2Document19 pagesRamma Clauses: Group 2Nguyễn Thị Diểm PhúcNo ratings yet

- Unitplanassessment 4Document13 pagesUnitplanassessment 4api-317825538No ratings yet

- Rubrics For Impromptu SpeechDocument2 pagesRubrics For Impromptu Speechdanilo jr siquigNo ratings yet

- Elaine 3rd Monthly Test English and Reading 4Document4 pagesElaine 3rd Monthly Test English and Reading 4Miriam VillegasNo ratings yet

- Book 1 Beginners 2010 Second EditionDocument133 pagesBook 1 Beginners 2010 Second Editionpapeleria la estrellaNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Tense (Unit 10)Document31 pagesSimple Past Tense (Unit 10)Kerak Telor PetjahNo ratings yet

- Inspired Level 1 Guided Speaking - Units5 6 TN PDFDocument1 pageInspired Level 1 Guided Speaking - Units5 6 TN PDFOSRAMANo ratings yet

- Types of SyllabusDocument16 pagesTypes of SyllabusRegina CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 Varieties and Registers of Spoken and Written LanguageDocument4 pagesLesson 4 Varieties and Registers of Spoken and Written LanguageKesiah FortunaNo ratings yet

- SpectrumPhonics SampleBook Grade1.compressed PDFDocument16 pagesSpectrumPhonics SampleBook Grade1.compressed PDFPilar Morales de Rios80% (5)

- The Logic of The History of IdeasDocument351 pagesThe Logic of The History of IdeasJorge Mora100% (1)

- La Vida EstudiantilDocument9 pagesLa Vida EstudiantilHerlleyNo ratings yet

- Common ErrorsDocument16 pagesCommon ErrorsmurariNo ratings yet

- 8204E Evaluation Resource PDFDocument3 pages8204E Evaluation Resource PDFSukhdave SinghNo ratings yet

- Tugas Tuton 2 PBIS4216 (Structure III)Document3 pagesTugas Tuton 2 PBIS4216 (Structure III)Ryo ChezterNo ratings yet

- Narrative-Essay-Marking-Scheme IXDocument1 pageNarrative-Essay-Marking-Scheme IXMelinda BrejeNo ratings yet

- Elt 111 Report Aileen MalonesDocument9 pagesElt 111 Report Aileen MalonesCOLLEGEBADODAW PRECYNo ratings yet

- English To Romanian WorksheetsDocument5 pagesEnglish To Romanian WorksheetsBetea Rebeca0% (1)

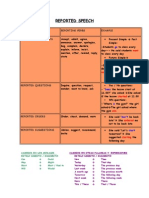

- Cuadro Reported SpeechDocument1 pageCuadro Reported SpeechMJOSERMNo ratings yet

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (85)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Body Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.From EverandBody Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Meditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionFrom EverandMeditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinFrom EverandA Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundFrom Everand1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Summary of Ryan Holiday's Discipline Is DestinyFrom EverandSummary of Ryan Holiday's Discipline Is DestinyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsFrom EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- How Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideFrom EverandHow Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideNo ratings yet

- Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSurrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessFrom EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)