Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors PDF

Uploaded by

Stacey Woods0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

50 views7 pagesAdverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase

Original Title

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAdverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

50 views7 pagesAdverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors PDF

Uploaded by

Stacey WoodsAdverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Clinical Geriatrics

Published on Clinical Geriatrics (http://clinicalgeriatrics.com)

Home > Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase

Inhibitors

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

Thu, 2/3/11 - 2:40pm

1 Comments

Issue Number: Volume 19 - Number 1 - January 2011 [1]

Section: Feature

Citation:

Clinical Geriatrics 2011;19(1):27-30.

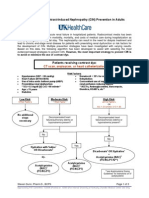

PatelTable1.png [2]

PatelTable2.png [3]

PatelTable3.png [4]

Authors:

Birju B. Patel, MD, FACP, and N. Wilson Holland, MD, FACP

Introduction

Dementia is an underrecognized and underdiagnosed condition in the rapidly growing elderly

population. It is estimated that approximately 24 million people worldwide had dementia in

2005.

1

Alzheimers disease is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60% to 80% of

all dementia cases.

2

In the United States alone, 5.3 million people have Alzheimers disease

and someone develops Alzheimers disease every 70 seconds. It is the seventh leading cause of

death in this country. The annual healthcare system costs are estimated at $172 billion.2 Our

healthcare system is increasingly impacted by the silver tsunami. The U.S. Census Bureau

estimates that the elderly population will double to an estimated 80 to 90 million individuals by

the year 2050.

3

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are typically prescribed to treat symptoms of cognitive

and functional decline in patients with Alzheimers disease and other dementias.

4,5

In 1993,

tacrine hydrochloride became the first AChEI approved by the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Alzheimers disease, but it was later primarily replaced

by second-generation AChEIs due to more favorable side-effect profiles and safety concerns;

there have been reports of hepatotoxicity with tacrine use.

6

There are currently three second-

generation AChEIs approved by the FDA: donepezil hydrochloride (1997); rivastigmine tartrate

(2000); and galantamine hydrobromide (2001; Table I). Donepezil is labeled for use in all stages

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

1 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

of dementia. Galantamine and rivastigmine are labeled for use in mild-to-moderate dementia.

[2]

As the use of these AChEIs increases, there are ongoing controversies about their

cost-effectiveness and modest efficacy.

7-10

By inhibiting the cholinesterase enzyme from

breaking down acetylcholine (ACh), these agents lead to increased synaptic levels of ACh.

Although these medications are intended to increase cholinesterase activity specifically in the

brain, the side effects manifest as symptoms that can be expected from both central and

peripheral cholinergic excess. Many clinicians are not aware of the array of potential side effects

of these medications (Table II).

[3]

This article discusses the side effects, tolerability, and precautions in the use of AChEIs. The

following case vignettes illustrate some adverse effects of these medications.

Case 1

Dr. B was an 88-year-old man who had had dementia for several years. His medical history

included serial transient ischemic attacks and prostate cancer. A computed tomography (CT)

scan of his brain showed lacunar infarcts and small vessel ischemic changes. Dr. B was initially

started on donepezil 5 mg daily, and this was increased after several months to 10 mg daily

Approximately 3 months into his treatment, he started having loose, watery stools up to 6 times

per day. The patient had no abdominal pain, fever, chills, or recent history of travel. His

laboratory evaluation showed a normal chemistry profile and normal thyroid studies. Stool

studies were performed, results of which were also unremarkable. Because of the severity of his

diarrhea, his family made an appointment for him to see a local gastroenterologist. Dr. B

underwent a colonoscopy, which was unrevealing other than the finding of noninflamed

diverticula. His wife also noticed that he had developed rhinorrhea during this period of time. He

subsequently presented to a geriatric primary care clinic, and donepezil was discontinued. Dr. B

was seen in follow-up 2 weeks later, and both the rhinorrhea and diarrhea had completely

resolved.

Case 2

Mr. R was an 85-year-old man with a history of hypertension, severe osteoarthritis, and

asbestosis, as well as a several-month history of increasing confusion. Results of laboratory

studies were unremarkable, including normal thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12

levels. A CT scan of the brain showed small vessel ischemic changes and chronic lacunar

infarcts in the internal capsule. A baseline electrocardiogram was not obtained, but chest

roentgenography showed pleural plaques. Cognitive testing revealed moderate dementia, and

he was started on galantamine 4 mg twice daily, which was titrated to 8 mg twice daily after 6

weeks.

Mr. R presented to the emergency department (ED) with syncope several months after the

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

2 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

galantamine was titrated. Initial workup in the ED revealed type II second-degree atrioventricular

block and bradycardia. Telemetry monitoring for 48 hours showed no significant arrhythmias. An

echocardiogram revealed normal systolic function and mild diastolic dysfunction. The patient

was evaluated by a cardiologist, who felt that the likely cause of his syncope was type II second-

degree atrioventricular block associated with galantamine. Galantamine was subsequently

discontinued.

Side Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

The cholinergic hypothesis of age and Alzheimers diseaserelated cognitive deficits states that

decreased levels of ACh in the brain lead to cognitive deficits.

11

The most common cholinergic

side effects of AChEIs involve the gastrointestinal tract. These side effects are usually mild and

have been reported to occur in approximately 20% of patients taking these medications.

12

Among the side effects reported in the package inserts of currently available second-

generation AChEIs are nausea (11%-47%), vomiting (10%-31%), diarrhea (5%-19%), and

anorexia (4%-17%).

13

These gastrointestinal side effects are relatively well known by

clinicians,

14

and can be minimized with the use of longer titration periods and the administration

of these medications with food.

15

There are also lesser-known side effects associated with AChEIs, occurring in fewer than 5% of

patients, that clinicians who care for elderly patients should be aware of.

16

Some of these side

effects can be life-threatening, and include rhinitis, fatigue, leg cramps, insomnia, abnormal

dreams, myasthenia, asthenia, tremor, dizziness, headaches, bradycardia, orthostatic

hypotension, syncope, urinary incontinence, seizures, gastrointestinal hemorrhage,

extrapyramidal symptoms, and, very rarely, liver dysfunction including hepatitis.

17,18

There have

been some reports of hallucinations, aggressive behavior, and agitation, which resolved on dose

reduction or discontinuation of treatment.

13

Severe vomiting with esophageal rupture has also

been reported with the use of rivastigmine.

19

Precautions in the Use of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

Clinicians should be cautious when prescribing AChEIs to patients with previous hypersensitivity

or adverse reactions to these medications. Patients with a history of bradycardia, heart block,

and syncope are at a much higher risk of adverse effects from central and peripheral muscarinic

stimulation resulting in a vagotonic effect on the heart. In a recent study by Gill et al,

20

hospital

visits for syncope were more frequent in those who were taking AChEIs versus controls (31.5 vs

18.6 events per 1000 patient-years). Furthermore, those who were taking AChEIs were more

likely to have hospital visits for bradycardia, permanent pacemaker insertion, and hip fracture.

Syncope can lead to hospitalization, increased healthcare costs, and increased risk of falls and

fractures in the elderly.

20

Cholinergic agents can reduce the seizure threshold; therefore, AChEIs should be prescribed

with a great deal of caution in those with a history of seizure disorder and chronic alcoholism.

Excessive stimulation of nicotinic receptors can lead to muscle cramps and weakness. Patients

who are at risk of developing gastrointestinal ulcers and those who are taking nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs should be carefully followed for symptoms due to the increased

secretion of gastric acid stimulated by increased levels of ACh. Asthma and chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease can also be exacerbated with the use of AChEIs due to increased bronchial

secretions. Rarely, these medications can cause bladder outflow obstruction and urinary

incontinence.

21

Weight loss, usually due to the gastrointestinal side effects, is also a concern.

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

3 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

Patients with low body weight should be carefully evaluated for risks versus benefits prior to

initiating treatment with these agents.

Increasing the Tolerability of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

When side effects and tolerability issues are encountered with AChEIs, several techniques can

be useful. Gradual dose titration, as previously mentioned, can be beneficial in patients who are

experiencing gastrointestinal side effects. Lowering the dose and administering these

medications with meals can also be beneficial. Switching the time of administration can be

important; for example, dosing donepezil in the morning or during lunch can be useful in

preventing the vivid, threatening dreams and nightmares that can occur when taking this

medication. If switching an AChEI is necessary, it is important to stop the offending agent and

let the side effects resolve prior to the initiation of another AChEI. Decreasing the dose

temporarily for a few days can also be helpful in increasing tolerability. A 4- to 6-week dose

titration is often necessary to achieve higher dosing while minimizing side effects.

22

Conclusion

It is important for clinicians to be aware of the side effects of AChEIs. There are ongoing debates

about the efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and optimal duration of use of these agents.

23,24

These

medications are currently the mainstay of treatment of dementia and Alzheimers disease, but

should be used with a great degree of caution and ongoing monitoring. The decision to use

specific AChEIs is based on cost, the healthcare providers experience with these medications,

and individual patient tolerability, since all AChEIs have similar efficacy.

25,26

The potential side

effects, efficacy, and cost of these medications should be discussed with patients and their

caregivers. Expected benefits versus potential risks of treatment also have to be discussed and

carefully weighed for patients prior to the initiation of these medications.

27

Several clinical pearls can be gleaned related to the use of AChEIs (Table III). As the case

vignettes demonstrate, knowing the side effects of these types of medications may prevent

unnecessary or invasive workups in the frail, elderly population. Clinicians who care for elderly

patients should always be looking for new symptoms and their possible relationships to

medications. Most importantly, rather than adding more medications to treat side effects,

clinicians should be reducing polypharmacy and stopping the medications that contribute to

untoward effects. Although syncope and dizziness are less frequently reported side effects,

nevertheless, in our experience in a large outpatient geriatric clinic, we have seen numerous

cases of syncope associated with AChEIs. Because of this, one should pay close attention to

orthostatic findings and get baseline electrocardiograms prior to starting these agents.

Physicians and other healthcare practitioners should always remember the basic premise First,

do no harm before initiating any treatment.

[4]

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

From the Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics and Gerontology, Emory University

School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, and the Department of Geriatrics and Extended Care, Atlanta

VA Medical Center, Decatur, GA.

References

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al; Alzheimers Disease International. Global prevalence of

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

4 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

dementia: A Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366(9503):2112-2117.

2. Alzheimers Association. 2010 Alzheimers disease facts and figures. http://www.alz.org

/documents_custom/report_alzfactsfigures2010.pdf [5]. Accessed December 13, 2010.

3. Census bureau reports worlds older population projected to triple by 2050 [press release].

U.S. Census Bureau Newsroom. June 23, 2009.

4. Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimers disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2006;(1):CD005593.

5. Clark CM, Karlawish JH. Alzheimer disease: Current concepts and emerging diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(5):400-410.

6. Watkins PB, Zimmerman HJ, Knapp MJ, Gracon SI, Lewis KW. Hepatotoxic effects of tacrine

administration in patients with Alzheimers disease. JAMA 1994;271(13):992-998.

7. Morden NE, Zerzan JT, Larson EB. Alzheimers disease medication: Use and cost projections

for Medicare Part D. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(4):622-624.

8. Neumann PJ, Hermann RC, Kuntz KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment

of mild or moderate Alzheimers disease. Neurology 1999;52(6):1138-1145.

9. Hauber AB, Gnanasakthy A, Mauskopf JA. Savings in the cost of caring for patients with

Alzheimers disease in Canada: An analysis of treatment with rivastigmine. Clin Ther

2000;22(4):439-451.

10. Ames D, Kaduszkiewicz H, van den Bussche H, Zimmermann T, Birks J, Ashby D. For

debate: Is the evidence for the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in the symptomatic treatment

of Alzheimers disease convincing or not? Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20(2):259-292. Published

Online: February 6, 2008.

11. Cummings JL, Kaufer D. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Alzheimers disease: The cholinergic

hypothesis revisited. Neurology 1996;47(4):876-883.

12. Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-

controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimers disease. Donepezil Study Group.

Neurology 1998;50(1):136-145.

13. Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: Evidence-based

recommendations. Focus 2004;2(2):239-252.

14. Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors and clinical practice: Evidence-based

recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11(2):131-145.

15. Agronin ME. Alzheimer Disease and Other Dementias: A Practical Guide. 2nd ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

16. Physicians Desk Reference. 2011. 65th ed. Montvale, NJ: PDR Network; 2010.

17. Inglis F. The tolerability and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia.

Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2002;(127):45-63.

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

5 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

18. Gauthier S. Cholinergic adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer s disease:

Epidemiology and management. Drugs Aging 2001;18(11):853-862.

19. Novartis Exelon labeling update reflects report of esophageal rupture. The Pink Sheet

2001;63:24.

20. Gill SS, Anderson GM, Fischer HD, et al. Syncope and its consequences in patients with

dementia receiving cholinesterase inhibitors: A population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med

2009;169(9):867-873.

21. Hashimoto M, Imamura T, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, Mori E. Urinary incontinence: An

unrecognized adverse effect with donepezil. Lancet 2000;356(9229):568.

22. Mimica N, Presecki P. Side effects of approved antidementives. Psychiatr Danub

2009;21(1):108-113.

23. Graff MJ, Adang EM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, et al. Community occupational therapy for older

patients with dementia and their care givers: Cost effectiveness study. BMJ

2008;336(7636):134-138. Published Online: January 2, 2008.

24. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and

memantine for treating dementia: Evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern

Med 2008;148(5):379-397.

25. Qaseem A, Snow V, Cross JT Jr, et al; American College of Physicians/American Academy

of Family Physicians Panel on Dementia. Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: A

clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy

of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(5):370-378.

26. Trinh NH, Hoblyn J, Mohanty S, Yaffe K. Efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment

of neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional impairment in Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis.

JAMA 2003;289(2):210-216.

27. Lindstrom HA, Smyth KA, Sami SA, et al. Medication use to treat memory loss in dementia:

Perspectives of persons with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia 2006;5(1):27-50.

image description [6] image description [7]

Feature

HMP Communications LLC (HMP) is the authoritative source for comprehensive information and

education servicing healthcare professionals. HMP Communications LLC (HMP) is the

authoritative source for comprehensive information and education servicing healthcare

professionals. HMPs products include peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed medical journals,

national tradeshows and conferences, online programs and customized clinical programs. HMP

is a wholly owned subsidiary of HMP Communications Holdings LLC. 2010 HMP

Communications

Source URL: http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/articles/Adverse-Effects-Acetylcholinesterase-Inhibitors

Links:

[1] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/Volume-19-Issue-1-January-2011

[2] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/files/PatelTable1.png

[3] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/files/PatelTable2.png

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

6 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

[4] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/files/PatelTable3.png

[5] http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/report_alzfactsfigures2010.pdf

[6] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/printmail/4269

[7] http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

Adverse Effects of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors http://clinicalgeriatrics.com/print/4269

7 of 7 11/22/2011 2:33 AM

You might also like

- Id 397 TeicoplaninDocument2 pagesId 397 TeicoplaninStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Switching Ace-Inhibitors: Change To Change From Enalapril Quinapril RamiprilDocument2 pagesSwitching Ace-Inhibitors: Change To Change From Enalapril Quinapril RamiprilGlory Claudia KarundengNo ratings yet

- Antithrombotic Therapy For VTE DiseaseDocument13 pagesAntithrombotic Therapy For VTE DiseaseStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Adults at NUH2011 FinalDocument2 pagesTherapeutic Drug Monitoring in Adults at NUH2011 FinalStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Palliative2 Nausea MedtableDocument2 pagesPalliative2 Nausea MedtableStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Antibiotik WhoDocument49 pagesAntibiotik WhodjebrutNo ratings yet

- J Jacadv 2023 100389Document12 pagesJ Jacadv 2023 100389Edward ElBuenoNo ratings yet

- IDSA Releases Guidance On Antibiotic Selection For Gram-Negative Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Infections - ACP Internist Weekly - ACP InternistDocument3 pagesIDSA Releases Guidance On Antibiotic Selection For Gram-Negative Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacterial Infections - ACP Internist Weekly - ACP InternistStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Management of Bacterial and Fungal Infections in Cirrhosis JOH 2021Document17 pagesManagement of Bacterial and Fungal Infections in Cirrhosis JOH 2021Francisco Javier Gonzalez NomeNo ratings yet

- 2023 ESPEN Practical and Partially Revised Guideline - Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitDocument19 pages2023 ESPEN Practical and Partially Revised Guideline - Clinical Nutrition in The Intensive Care UnitStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Appropriate Use of Laxatives in The Older PersonDocument7 pagesAppropriate Use of Laxatives in The Older PersonStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Critical CareDocument8 pagesCritical CareDzikrul Haq KarimullahNo ratings yet

- Drug Information Center/KAUH: Selecting Gluten-Free Antibiotics in Celiac DiseaseDocument6 pagesDrug Information Center/KAUH: Selecting Gluten-Free Antibiotics in Celiac DiseaseStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Splenectomy Guideline Final 2012Document6 pagesSplenectomy Guideline Final 2012Stacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Multimorbidity Clinical Assessment and Management 1837516654789Document22 pagesMultimorbidity Clinical Assessment and Management 1837516654789Stacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Selection - The Clinical AdvisorDocument6 pagesAntibiotic Selection - The Clinical AdvisorStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobials at The End of LifeDocument2 pagesAntimicrobials at The End of LifeStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Tamiflu PrescribingDocument26 pagesTamiflu PrescribingStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Procoagulant GuidelineDocument30 pagesProcoagulant GuidelineStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Potasio. 2014.Document19 pagesPotasio. 2014.Nestor Enrique Aguilar SotoNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Insulin 2013Document3 pagesPreoperative Insulin 2013Stacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- C.a.U.S.E. - Cardiac Arrest Ultra-Sound Exam - A Better Approach To Managing Patients in Primary Non-Arrhythmogenic Cardiac ArrestDocument2 pagesC.a.U.S.E. - Cardiac Arrest Ultra-Sound Exam - A Better Approach To Managing Patients in Primary Non-Arrhythmogenic Cardiac ArrestStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Contrast NephRopathy GuidelinesDocument3 pagesContrast NephRopathy GuidelinesStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Biomarkers of SepsisDocument8 pagesBiomarkers of SepsisStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- StrokeDocument2 pagesStrokeStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- The ABC of Weaning Failure - A Structured ApproachDocument9 pagesThe ABC of Weaning Failure - A Structured ApproachArul ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- Stimulant May Speed Antidepressant Response Time in ElderlyDocument3 pagesStimulant May Speed Antidepressant Response Time in ElderlyStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Fluid Choices Impact Outcome in Septic ShockDocument7 pagesFluid Choices Impact Outcome in Septic ShockStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Elderly Patients Making Wise ChoicesDocument6 pagesElderly Patients Making Wise ChoicesStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- Airway Clearance in The Intensive Care UnitDocument5 pagesAirway Clearance in The Intensive Care UnitStacey WoodsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Acute Bioligic CrisisDocument141 pagesAcute Bioligic CrisisJanelle MatamorosaNo ratings yet

- Case Study FIXDocument66 pagesCase Study FIXPatrick Kelvian100% (1)

- NURSING PRACTICE Test COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING AND CARE OF THE MOTHER AND CHILDDocument8 pagesNURSING PRACTICE Test COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING AND CARE OF THE MOTHER AND CHILDJhannNo ratings yet

- Open Repair of Ventral Incisional HerniasDocument23 pagesOpen Repair of Ventral Incisional HerniasElena Silvia SoldeanuNo ratings yet

- Hospital Case Study FlexsimDocument2 pagesHospital Case Study FlexsimMano KanthanathanNo ratings yet

- Administration of Medication Through Nasogastric TubeDocument10 pagesAdministration of Medication Through Nasogastric TubeBlinkeen Woods100% (1)

- Dysphagia in CPDocument19 pagesDysphagia in CPMaria Alejandra RengifoNo ratings yet

- Types of Stomas and Loop Ostomy CareDocument8 pagesTypes of Stomas and Loop Ostomy CareRadhiyatul Ashiqeen Binti MoktarNo ratings yet

- VijayDocument12 pagesVijaykishanNo ratings yet

- HR 1701 - Commending Medical and Nursing Board TopnotchersDocument2 pagesHR 1701 - Commending Medical and Nursing Board TopnotchersBayan Muna Party-listNo ratings yet

- Zoloft SertralineDocument1 pageZoloft SertralineAdrianne Bazo100% (1)

- Managing Hypertension Through Lifestyle ChangesDocument3 pagesManaging Hypertension Through Lifestyle ChangespsychyzeNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Patients Receiving Palliative CareDocument9 pagesPain Management in Patients Receiving Palliative CareelbaNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Management of Acute Kidney Injury in Adults - UpToDateDocument13 pagesOverview of The Management of Acute Kidney Injury in Adults - UpToDateDaniely FreitasNo ratings yet

- SURVEILANS HEALTH CARE ASSOCIATED INFECTIONSDocument49 pagesSURVEILANS HEALTH CARE ASSOCIATED INFECTIONSfebri12No ratings yet

- Regulation For Optical Center and Optometry Services FinalDocument15 pagesRegulation For Optical Center and Optometry Services FinalsafasayedNo ratings yet

- Tonsillitis, Tonsillectomy and Hodgkin's LymphomaDocument5 pagesTonsillitis, Tonsillectomy and Hodgkin's LymphomaD.E.P.HNo ratings yet

- Just Culture CommissionDocument27 pagesJust Culture CommissionAlina PetichenkoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Activity IntoleranceDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plan for Activity IntoleranceShermane Criszen F. SallanNo ratings yet

- Thesis MedicineDocument110 pagesThesis MedicineVenkatesh KorapakaNo ratings yet

- Nurses and Hierarchy JOB RESPONSIBILITYDocument9 pagesNurses and Hierarchy JOB RESPONSIBILITYSaravanan MRNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety Incident Report Form SummaryDocument9 pagesPatient Safety Incident Report Form SummaryJhun SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Latissimus Dorsi Flap To BreastDocument13 pagesLatissimus Dorsi Flap To Breastokida192100% (1)

- Medication Management in Older Adults - A Concise Guide For Clinicians - S. Koch, Et Al., (Springer, 2010) WWDocument143 pagesMedication Management in Older Adults - A Concise Guide For Clinicians - S. Koch, Et Al., (Springer, 2010) WWGeorgianaRamonaNo ratings yet

- HW 1 PathoDocument4 pagesHW 1 PathoBryan RallomaNo ratings yet

- 1556188104-Workshop Overview On Stoma CareDocument31 pages1556188104-Workshop Overview On Stoma CareZuldi ErdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Complications of Bleeding Disorders in PregnancyDocument11 pagesComplications of Bleeding Disorders in PregnancyNursing ReviewerNo ratings yet

- Discharge Plan Medications Exercise Lifestyle Changes DietDocument4 pagesDischarge Plan Medications Exercise Lifestyle Changes Dietlexther_latidoNo ratings yet

- Feeding by Nasogastric TubesDocument3 pagesFeeding by Nasogastric TubesLheidaniel MMM.No ratings yet

- Nutrition diagnosis: Imbalanced nutrition less than requirementsDocument3 pagesNutrition diagnosis: Imbalanced nutrition less than requirementsIlisa ParilNo ratings yet