Professional Documents

Culture Documents

12

Uploaded by

api-19977019Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

12

Uploaded by

api-19977019Copyright:

Available Formats

BOTM_C01.

QXD 26/9/05 4:12 pm Page 12

12 CHAPTER 1 · INTRODUCTION – THE UNIQUE EVOLUTION OF TOURISM AS ‘BUSINES S’

Evolutionary theories have an obvious attraction – in many case they seem to work well,

explaining how tourism to, for example, Torremolinos has changed in the last 50 years

(see BBC, 1996). But difficulties with this kind of approach have emerged:

■ They only make sense with respect to the destination from the perspective of the

tourism-generating country – in the case of Torremolinos, or the Spanish Costas by

extension, with respect to visitors from the UK and other Northern European coun-

tries. Do they really explain the growth in Spanish domestic tourism?

■ The logical extension of these theories is that all destinations would ultimately be

full of working-class psychocentric tourists only.

■ Ultimately where do the rich allocentric tourists end up? They’re going to run out

of possible destinations to discover.

Some of these problems can be countered by recognising that any particular resort is not

restricted to one lifecycle – they can reinvent themselves and attract a further round of

visitation by upper-class allocentrics.

Case 1.3 Atlantic City – a case of reinvention

While first impressions would suggest Atlantic City is little more than a poor man’s Vegas, this now chintzy

gambling haven hides a complex and original history. Its current reputation began in the latter half of the

twentieth century. However, tourism has played a part in Atlantic City’s history for much longer, since the

early 1800s in fact.

Absecon Island, home to Atlantic City, was also home to a prominent pioneering family, the Leeds. The

Leeds set Atlantic City on a tourism lifecycle that is quite unlike that of most other tourism destinations.

The first ever industry on Absecon Island was tourism, which began with a boarding house opened by

Jeremiah Leeds’ second wife. The original idea was to turn the island into a seaside health resort, but the

isolated location and the lack of transport links were to be a problem. To solve this, in 1852 the

Camden–Atlantic City railroad was born, and it was to set Atlantic City on a path of rapid change and devel-

opment. Over the next three decades, following the initial influx of tourists by train, Atlantic City developed

various alternative routes for its potential visitors to use: a busy seaport, a road from the mainland and an

additional railway line.

With the rapid increase in the number of guests, the need for accommodation also grew. A vast number

of then luxurious hotels were opened to cater for the influx of tourists, as were amusement parks to enter-

tain them. In 1870, Atlantic City’s most famous landmark was built – the Boardwalk. The first in the world,

it began a trend and the boardwalk has become a symbol of seaside holiday resorts worldwide. At six miles

long, the Boardwalk is still today at the very centre of Atlantic City’s tourism industry.

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a great time for Atlantic City; industry, population and tourist

numbers were growing. Its variety of amenities and amusements meant that it had something to interest

everyone, and for a long while Atlantic City was the place to be. Like many other destinations, however, it

suffered from seasonality, and while the summer months were buzzing, it struggled out of season. One

solution to this came in 1921, with the first annual Miss America pageant. Along with the Boardwalk, the

pageant has become synonymous with Atlantic City, and has brought followers from all over the world.

However, this was all to change. Before long, plenty of other destinations had taken their lead from

Atlantic City’s early success, and the once popular seaside resort looked dated in comparison. Combined

with the increase in air travel after the Second World War, Atlantic City was soon losing out to more modern

and glamorous international competitors.

By 1960, Atlantic City was definitely not ‘the place to be’. Something was needed to restore the city’s

former glory. That something was thought to be gambling. In 1976, Atlantic City was given a second

chance, with the passing of the Casino Gambling Referendum. Suddenly the amusement arcades, tacky

souvenir shops and worn-out boarding-houses were replaced with top-class restaurants, big-name hotels

and glamorous casinos. This revamp did wonders for Atlantic City, and, along with providing over 45,000

jobs, succeeded in bringing in new and different types of visitors and, more importantly, restoring the city’s

reputation as a credible holiday destination.

Albeit with deteriorating credibility, this reputation continues today. Unfortunately, Atlantic City still expe-

riences the problems common to similar seaside resorts. Having a city so dependent on a gambling culture

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Tourism Flows: SunlustDocument1 pageTourism Flows: Sunlustapi-19977019No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Role of Management in Tourism Businesses: Table 1.4 The World's Top Tourism Destinations Relative To PopulationDocument1 pageThe Role of Management in Tourism Businesses: Table 1.4 The World's Top Tourism Destinations Relative To Populationapi-19977019No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Table 1.2 The World's Top Tourism DestinationsDocument1 pageTable 1.2 The World's Top Tourism Destinationsapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Case 1.2 The Bay of Naples - A Case of Changing TouristsDocument1 pageCase 1.2 The Bay of Naples - A Case of Changing Touristsapi-19977019No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'Document1 pageIntroduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'api-19977019No ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Tourism As An Evolutionary Process: LifecycleDocument1 pageTourism As An Evolutionary Process: Lifecycleapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- CoverpageDocument1 pageCoverpageapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Economic Impact: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'Document1 pageEconomic Impact: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'api-19977019No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Categorizing Cultures 33: Linear-Active Multi-Active ReactiveDocument1 pageCategorizing Cultures 33: Linear-Active Multi-Active Reactiveapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Key Words: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'Document1 pageKey Words: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'api-19977019No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Sufficient Earnings To Be Able To Spend Money On Holidays: Early Tourism BusinessesDocument1 pageSufficient Earnings To Be Able To Spend Money On Holidays: Early Tourism Businessesapi-19977019No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Case 1.1 Scarborough - A Case of TransformationDocument1 pageCase 1.1 Scarborough - A Case of Transformationapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Conclusion: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'Document1 pageConclusion: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'api-19977019No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Guided Reading: Index - HTMDocument1 pageGuided Reading: Index - HTMapi-19977019No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Early Tourism BusinessesDocument1 pageEarly Tourism Businessesapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Some Basic Concepts: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'Document1 pageSome Basic Concepts: Chapter 1 Introduction - The Unique Evolution of Tourism As Business'api-19977019No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Jafar Jafari's Tourism Clock: Economics SociologyDocument1 pageJafar Jafari's Tourism Clock: Economics Sociologyapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Cover 2Document1 pageCover 2api-19977019No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- STI39Document1 pageSTI39api-19977019No ratings yet

- Who Is Normal, Anyway?: ChauvinismDocument1 pageWho Is Normal, Anyway?: Chauvinismapi-19977019No ratings yet

- ContentsDocument1 pageContentsapi-19977019No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CoverDocument1 pageCoverapi-19977019No ratings yet

- 48Document1 page48api-19977019No ratings yet

- 38 When Cultures Collide: Intercategory ComparisonsDocument1 page38 When Cultures Collide: Intercategory Comparisonsapi-19977019No ratings yet

- 24 When Cultures Collide: Shyness Distrust ChangeabilityDocument1 page24 When Cultures Collide: Shyness Distrust Changeabilityapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Culture Shock: Cultural Conditioning 19Document1 pageCulture Shock: Cultural Conditioning 19api-19977019No ratings yet

- 52 When Cultures CollideDocument1 page52 When Cultures Collideapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Categorizing Cultures 49Document1 pageCategorizing Cultures 49api-19977019No ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- 36 When Cultures CollideDocument1 page36 When Cultures Collideapi-19977019No ratings yet

- Don't Miss A Thing!: Esoteric Order GamersDocument7 pagesDon't Miss A Thing!: Esoteric Order GamersSubsailor68No ratings yet

- The Splendors and Miseries of Martingales Their History From The Casino To Mathematics - MazliakDocument419 pagesThe Splendors and Miseries of Martingales Their History From The Casino To Mathematics - MazliakJuan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Simplifying 50 Challenging Problems PDFDocument13 pagesSimplifying 50 Challenging Problems PDFian capiliNo ratings yet

- Siamese Porcelain and Other Tokens / by H.A. RamsdenDocument83 pagesSiamese Porcelain and Other Tokens / by H.A. RamsdenDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- Fugue Rules Document v1.51 - Released Under CC LicenceDocument27 pagesFugue Rules Document v1.51 - Released Under CC LicenceDimitrios KarametosNo ratings yet

- Tricksters and The Trickster GodDocument20 pagesTricksters and The Trickster Godannu8No ratings yet

- Root Rules Quick ReferenceDocument2 pagesRoot Rules Quick ReferencevitaroNo ratings yet

- Lottery Boy Discussion GuideDocument2 pagesLottery Boy Discussion GuideCandlewick Press100% (1)

- DNGN v1.1 RulesDocument11 pagesDNGN v1.1 Rulessean.homenickNo ratings yet

- Form 20-F For 2017Document208 pagesForm 20-F For 2017Anonymous dgRAlFj8zNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Poker Profit CalculatorDocument25 pagesPoker Profit CalculatorLiam ThomasNo ratings yet

- Electric Manifesting BookDocument31 pagesElectric Manifesting Bookswcgluck94% (67)

- Staking Plans17.OriginalDocument47 pagesStaking Plans17.Originalseykid29No ratings yet

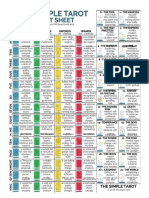

- Simple Tarot Cheat SheetDocument1 pageSimple Tarot Cheat SheetAmitNo ratings yet

- Probability and Combinatorics - Olivia KucanDocument3 pagesProbability and Combinatorics - Olivia Kucanapi-221860675No ratings yet

- Bard College Creation GuideDocument12 pagesBard College Creation GuideJ Schroeder0% (1)

- Record US JackpotsDocument4 pagesRecord US JackpotsGary DetmanNo ratings yet

- Assign 3 2019Document3 pagesAssign 3 2019sovrinNo ratings yet

- In Memoriam Rozanne S., Founder. Overeaters Anonymous 1929-2014Document1 pageIn Memoriam Rozanne S., Founder. Overeaters Anonymous 1929-2014lady_abrynaNo ratings yet

- "THE MALLARD" August 2017Document16 pages"THE MALLARD" August 2017ggmbeneficeNo ratings yet

- Make Your Kingdom (Fan Translation)Document302 pagesMake Your Kingdom (Fan Translation)triad3204No ratings yet

- The Crazy Cards Icebreaker ChallengeDocument9 pagesThe Crazy Cards Icebreaker ChallengeEric SunNo ratings yet

- The Storyteller (Saki) - H. H. Munro (Saki) (1870-1916)Document3 pagesThe Storyteller (Saki) - H. H. Munro (Saki) (1870-1916)Akshay Lalwani100% (1)

- Yahtzee Score Card PDFDocument1 pageYahtzee Score Card PDFjoe libbeyNo ratings yet

- GS Form No. 30 - Voluntary Closure-Non-Renewal of Gaming License Notification FormDocument1 pageGS Form No. 30 - Voluntary Closure-Non-Renewal of Gaming License Notification FormJP De La PeñaNo ratings yet

- With ReplacementDocument9 pagesWith ReplacementIrene BaikNo ratings yet

- 100+ Tambola Ticket Printable Free (Republic Day / Independence Day)Document30 pages100+ Tambola Ticket Printable Free (Republic Day / Independence Day)Ashish50% (4)

- Walking in BuranoDocument9 pagesWalking in BuranoRubén Arroyo SanzNo ratings yet

- Trio ENDocument2 pagesTrio ENbrassoyNo ratings yet

- Middara ReglamentoDocument76 pagesMiddara ReglamentoAdrianMuñozOrtuñoNo ratings yet

- Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandFrom EverandChesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier IslandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (38)

- Will's Red Coat: The Story of One Old Dog Who Chose to Live AgainFrom EverandWill's Red Coat: The Story of One Old Dog Who Chose to Live AgainRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- Grandma Gatewood's Walk: The Inspiring Story of the Woman Who Saved the Appalachian TrailFrom EverandGrandma Gatewood's Walk: The Inspiring Story of the Woman Who Saved the Appalachian TrailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (308)

- Smokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersFrom EverandSmokejumper: A Memoir by One of America's Most Select Airborne FirefightersNo ratings yet

- Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer: An Edgar Award WinnerFrom EverandManhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer: An Edgar Award WinnerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (84)

- The Last Empty Places: A Journey Through Blank Spots on the American MapFrom EverandThe Last Empty Places: A Journey Through Blank Spots on the American MapRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)