Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Practicum Manual For Student-Teachers

Uploaded by

Dennis Esik Maligaya0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views6 pagespracticum manual for student-teachers

Original Title

Practicum manual for student-teachers

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentpracticum manual for student-teachers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views6 pagesPracticum Manual For Student-Teachers

Uploaded by

Dennis Esik Maligayapracticum manual for student-teachers

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Development and validation of an instrument

to measure the postgraduate clinical learning

and teaching educational environment for

hospital-based junior doctors in the UK

S. ROFF

1

, S. MCALEER

1

& A. SKINNER

2

1

Centre for Medical Education, Dundee University Medical School, UK;

2

Department of

Paediatrics, City Hospital NHS Trust, Birmingham, UK

SUMMARY This paper describes the development and validation

of a 40-item inventory, the Postgraduate Hospital Educational

Environment Measure (PHEEM), by researchers in Scotland and

the West Midlands using a combination of grounded theory and

Delphi process. The instrument has since returned an alpha

reliability >0.91 in two administrations in England and may be a

useful instrument in the quality assurance process for postgraduate

medical education and training.

Background

Genn (2001) and Harden (2001) have pointed to the

potential of the understanding of learning environments

and sub-environments for managing curriculum develop-

ment and change. Stimulated by their suggestions for action

research in their earlier paper (Genn & Harden, 1986), Roff

et al. (1997) developed the 50-item Dundee Ready Education

Environment Measure with a panel of nearly 100 medical

educators and 1000 students to measure and diagnose

undergraduate educational climates in the health professions.

This instrument has been translated into Spanish,

Portuguese, Arabic, Swedish, Malay and Thai and used in

several settings including the Middle East, Thailand

(Primparyon et al., 2000), Nepal and Nigeria (Roff et al.,

2001) and the West Indies (Bassaw et al., 2003). It is

currently being used in the UK, Canada, Ireland, Thailand,

China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Norway, Sweden, Brazil, the

West Indies and the Yemen.

A similar methodology has been utilized to develop and

validate an inventory to measure the postgraduate clinical

teaching and learning environment for hospital-based junior

doctors. A 40-item inventory was developed.

Methods

A form of grounded theory was used involving focus groups,

nominal groups and a Delphi panel drawn from the target

populations in two phases.

Phase 1

In the first stage of the process, a group of 12 Scottish

Postgraduate Deans, Postgraduate Educational Supervisors,

Educational Advisors and PRHOs met in January 2000 to

agree an initial list of possible items for inclusion in the

inventory based on a literature review (conducted by

McAleer and Roff) of articles retrieved from MEDLINE

and mission statements such as the GMCs The New Doctor,

together with their own observations of significant events/

critical incidents in PRHO training. The literature review had

generated 180 items which the stakeholders reduced to 150

items by eliminating repetitive material and consolidating

some items. These were critiqued by colleagues in the

Educational Development Unit of the Scottish Council for

Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education and the Centre

for Medical Education at the University of Dundee and on

the basis of their feedback concerning repetition and clarity

the inventory was further reduced to 132 items.

In order to validate and prioritize the 132 items into a

more manageable inventory, a random sample of 10% of

the current PRHOs in post in Scotland was sought. Since

direct access to PRHOs in post is difficult due to the

transience of their posts, they were contacted via their

Educational Supervisors. Two copies of the 132-item

preliminary inventory were mailed to the 175 Educational

Supervisors who were each asked to distribute them to one

or two PRHOs who would then return them directly to the

researchers in a return paid envelope which was coded for

the educational centre (hospital where the PRHO was in

post) but were otherwise anonymous. Respondents were

asked to rate the items on a Likert-type scale of 0 (not at all

important) to 4 (highly important) according to how impor-

tant they felt each item was in creating a good learning

environment for PRHOs. One hundred and seventeen

responses were returned which is 17% of the estimated 680

PRHOs in post at the time. Eight of these responses were

returned late, after the analysis had been undertaken.

Responses were received from 88 educational centres

including the four major areas of Glasgow, Edinburgh,

Dundee and Aberdeen as well as smaller centres such as

Oban, Ayr, Inverness and Kirkcaldy. This meant that 50% of

the Educational Supervisors had successfully distributed the

questionnaire to at least one trainee. Several Educational

Supervisors indicated that they did not have PRHOs in this

rotation and returned the questionnaires.

Correspondence: Sue Roff, Centre for Medical Education, Dundee University

Medical School, 484 Perth Road, Dundee DD2 1LR, UK. Email: s.l.roff@

dundee.ac.uk

Medical Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2005, pp. 326331

326 ISSN 0142159X print/ISSN 1466187X online/00/000326-6 2005 Taylor & Francis Group Ltd

DOI: 10.1080/01421590500150874

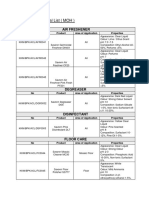

Table 1. The PHEEMitems grouped by sub-scale (negative items in italics).

I. Perceptions of role autonomy:

1 I have a contract of employment that provides information about hours of work

4 I had an informative induction programme

5 I have the appropriate level of responsibility in this post

8 I have to perform inappropriate tasks

9 There is an informative Junior Doctors Handbook

11 I am bleeped inappropriately

14 There are clear clinical protocols in this post

17 My hours conform to the New Deal

18 I have the opportunity to provide continuity of care

29 I feel part of a team working here

30 I have opportunities to acquire the appropriate practical procedures for my grade

32 My workload in this job is fine

34 The training in this post makes me feel ready to be an SpR/Consultant

40 My clinical teachers promote an atmosphere of mutual respect

14 items/max score 56 for this sub-scale

II. Perceptions of teaching:

2 My clinical teachers set clear expectations

3 I have protected educational time in this post

6 I have good clinical supervision at all times

10 My clinical teachers have good communication skills

12 I am able to participate actively in educational events

15 My clinical teachers are enthusiastic

21 There is access to an educational programme relevant to my needs

22 I get regular feedback from seniors

23 My clinical teachers are well organized

27 I have enough clinical learning opportunities for my needs

28 My clinical teachers have good teaching skills

31 My clinical teachers are accessible

33 Senior staff utilize learning opportunities effectively

37 My clinical teachers encourage me to be an independent learner

39 The clinical teachers provide me with good feedback on my strengths and weaknesses

15 items/max score 60 for this sub-scale

III. Perceptions of social support:

7 There is racism in this post

13 There is sex discrimination in this post

16 I have good collaboration with other doctors in my grade

19 I have suitable access to careers advice

20 This hospital has good quality accommodation for junior doctors, especially when on call

24 I feel physically safe within the hospital environment

25 There is a no-blame culture in this post

26 There are adequate catering facilities when I am on call

35 My clinical teachers have good mentoring skills

36 I get a lot of enjoyment out of my present job

38 There are good counselling opportunities for junior doctors who fail to complete their training satisfactorily

11 items/max score 44 for this sub-scale

Interpreting the sub-scales:

I. Perceptions of role autonomy:

014 very poor

1528 a negative view of ones role

2942 a more positive perception of ones job

4356 excellent perception of ones job

II. Perceptions of teaching:

015 very poor quality

1630 in need of some retraining

3145 moving in the right direction

4660 model teachers

(continued )

The postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment

327

One hundred and nine responses were fully completed

and returned in a timely manner. Fifty-eight (53%) were

from males and 51 (47%) were from females. Respondents

were asked to rate the 132 items in terms of how they

perceived the importance for the learning environment of

PRHOs. On a score of 04, 17 items were rated 3.5; 69

were rated 3.00 but 3.49 and the remaining 46 were rated

3.00. Several of the highest ranked items came from the end

of the 132-item list, suggesting that the length of the ques-

tionnaire was not a problem. Eight items received statistically

significant ratings from the males and females, but these

differences did not affect their broad categorization 3.00/

3.00 in the total rank order list. The reliability was high

with an alpha of 0.93.

The top ranking 90 items were retained for the second

version of the inventory.

Phase 2

A focus group (n 10) consisting of a consultant paedi-

atrician/assessor for the Royal College of Paediatrics and

Child Health, five Senior House Officers and four Specialist

Registrars in the Department of Paediatrics at a Birmingham

hospital was convened to review the 90 item inventory.

They were asked to rate the most relevant items in

their perception of a good clinical teaching and learning

environment for hospital-based junior doctors. Items

which three or more members of the focus group considered

least relevant were eliminated from the inventory. This

exercise in checking face validity among the stakeholders

reduced the inventory to 40 items, four of which (nos. 7, 8,

11, 13) are negative statements which have to be reversed for

scoring.

A nominal group of three of the researchers then identified

three sub-scalesPerceptions of role autonomy, Perceptions

of teaching and Perceptions of social support.

Results

The final instrument produced, the Postgraduate Hospital

Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM), is included

as Appendix 2. The items grouped by sub-scale are given

in Table 1. These were grouped into three sections, as

indicated below, together with the maximum score for each

sub-scale:

Perceptions of role autonomy: 14 4 56 max;

Perceptions of teaching: 15 4 60 max; and

Perceptions of social support: 11 4 44 max.

This is made up of the number of items in the sub-scale times

the maximum mark on a Likert scale of 04. The possible

maximum score is 160 and the minimum score is 0.

Information about administering PHEEM and scor-

ing and interpreting the students responses is given in

Appendix 1.

Discussion

The two-phase process of grounded theory research involv-

ing stakeholders from the relevant junior doctor grades

together with educational advisors and senior managers in

Scotland and Birmingham generated a 40-item inventory

with three sub-scales with apparent high face validity both

for the UK and in relation to other studies (Rotem et al.,

1995; Mitchell et al., 1999; Pololi & Price, 2000; Fernald

et al., 2001; Dolmans et al., 2004). Skinner has since

administered this 40-item inventory to 68 Senior House

Officers and 32 Specialist Registrars in Birmingham teach-

ing hospitals from a range of specialties and these results

are reported separately. The Postgraduate Hospital Edu-

cation Environment Measure (PHEEM) had an alpha

reliability of 0.91 in that administration. Clapham et al.

(2005) administered the PHEEM to 134 trainees at

nine Intensive Care Units in England and Scotland. The

Cronbachs alpha for this administration was 0.92 and no

rogue questions were detected by the alpha if item deleted

function in SPSS.

It is hoped that other researchers and managers of

junior doctor teaching and learning in the UK, and perhaps

beyond, will find it a useful quality assessment tool for

both single-use and longitudinal studies of hospital-

based clinical teaching and learning for junior doctors.

Newbury-Birch & Kamali (2001), for instance, have con-

cluded that the level of supervision provided by superiors,

flexibility and freedom in the job and level of participa-

tion in important decision-making are correlated with

levels of stress and anxiety in pre-registration house officers

in the UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor Norman Mackay,

Professor Graham Buckley and Dr Gellisse Bagnall for

support for data collection of this project and to Heather

Sutherland, Lynn Bell and Dr Danai Wangsaturaka for help

with data analysis. Funding for Phase 1 was provided by the

Table 1. Continued.

III. Perceptions of social support:

011 non-existent

1222 not a pleasant place

2333 more pros than cons

3444 a good supportive environment

Note: The PHEEM can also be used to pinpoint more specific strengths and weaknesses within the educational climate.

To do this one needs to look at the responses to individual items. Items that have a mean score of 3.5 or over are real

positive points. Any item with a mean of 2 or less should be examined more closely as they indicate problem areas. Items with a

mean between 2 and 3 are aspects of the climate that could be enhanced.

S. Roff et al.

328

Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical and Dental

Education.

Notes on contributors

SUE ROFF teaches in the Centre for Medical Education, Dundee

University Medical School, UK. She co-developed the Dundee Ready

Education Environment Measure. She is a lay member of the General

Medical Council Fitness to Practice Committee, the Unrelated Live

Transplants Regulatory Authority and the Postgraduate Medical

Education and Training Board.

SEAN MCALEER is Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Medical Education,

University of Dundee. He teaches on the Certificate, Diploma and

Masters Programme in Medical Education. His research interests are in

the areas of assessment, educational climate and learning styles.

ALYSON SKINNER is a Consultant Paediatrician with a special interest in

medical education at undergraduate and postgraduate level.

References

BASSAW, B., ROFF, S., MCALEER, S., ROOPNARINESIGN, S., DE LISLE, J.,

TEELUCKSINGH, S. & GOPAUL, S. (2003) Students perspectives of the

educational environment, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Trinidad,

Medical Teacher, 25, pp. 522526.

CLAPHAM, M., WALL, D. & BATCHELOR, A. (2005) Measuring

the educational climate in intensive care medicine, submitted for

publication.

DOLMANS, D.H.J.M., WOLFHAGEN, H.A.P., GERVER, W.J., DE GRAVE, W.

& SCHERPBIER, A.J.J.A. (2004) Providing physicians with feedback

on how they supervise students during patient contacts, Medical

Teacher, 25, pp. 409414.

FERNALD, D.H., STAUDENMAIER, A.C., TRESSLER, C.J., MAIN, D.S.,

OBRIEN-GONZALES, A. & BARLEY, G.E. (2001) Student perspectives

on primary care preceptorships: enhancing the medical student

preceptorship learning environment, Teaching and Learning in

Medicine, 13, pp. 1320.

GENN, J.M. (2001) AMEE medical education guide No.23 (Part 1):

curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical

educationa unifying perspective, Medical Teacher, 23, pp. 337344.

GENN, J.M. & HARDEN, R.M. (1986) What is medical education here

really like? Suggestions for action research studies of climates of medical

education environments, Medical Teacher, 8, pp. 111124.

HARDEN, R.M. (2001) The learning environment and the curriculum,

Medical Teacher, 23, pp. 335336.

MITCHELL, R., JACK, B. & MCQUADE, W. (1999) Mapping the cognitive

environment of a residency: an exploratory study of a maternal

and child health rotation, Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 11,

pp. 611.

NEWBURY-BIRCH, D. & KAMALI, F. (2001) Psychological stress,

anxiety, depression, job satisfaction, and personality characteristics

in preregistration house officers, Postgraduate Medicine Journal, 77,

pp. 109111.

POLOLI, L. & PRICE, J. (2000) Validation and use of an instrument to

measure the learning environment as perceived by medical students.

Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 12, pp. 201207.

PRIMPARYON, P., ROFF, S., MCALEER, S., POONCHAI, B. & PEMBA, S.

(2000) Educational environment, student approaches to learning

and academic achievement in a Thai nursing school, Medical Teacher,

22, pp. 359365.

ROFF, S., MCALEER, S., HARDEN, R.M., AL-QAHTANI, M., AHMED, A.U.,

DEZA, H., GROENEN, G. & PRIMPARYON, P. (1997) Development

and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment

Measure (DREEM), Medical Teacher, 19, pp. 295299.

ROFF, S., MCALEER, S., IFERE, O.S. & BHATTACHARYA, S. (2001) A global

diagnostic tool for measuring educational environment: comparing

Nigeria and Nepal, Medical Teacher, 23, pp. 378382.

ROTEM, A., GOODWIN, P. & DU, J. (1995) Learning in hospital settings.

Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 7, pp. 211217.

Appendix 1: Scoring the Postgraduate Hospital

Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM)

The PHEEM contains 40 statements covering a range of

topics directly relevant to the educational climate of Senior

House Officers (SHOs) and Specialist Registrars (SpRs)

(Appendix 1). The inventory can be administered by postal

or electronic survey or face-to-face. Respondents are asked to

read each statement carefully and to respond using a 5-point

Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly

disagree. It is important that each doctor applies the items

to their own current learning situation and respond to all 40.

Items should be scored: 4 for Strongly Agree (SA), 3

for Agree (A), 2 for Uncertain (U), 1 for Disagree (D) and 0

for Strongly Disagree (SD). However, four of the 40 items

(Numbers 7, 8, 11 and 13) are negative statements

and should be scored: 0 for SA, 1 for A, 2 for U, 3 for D

and 4 for SD.

The 40-item PHEEM has a maximum score of 160

indicating the ideal educational environment as perceived

by the SHO/SpR. A score of 0 is the minimum and would

be a very worrying result for any medical educator.

The following is an approximate guide to interpreting the

overall score:

040 very poor,

4180 plenty of problems,

81120

more positive than negative

but room for improvement, and

121160 excellent.

Interpret a score of 80 as an environment which is viewed

with considerable ambivalence by the SHOs/SpRs and as

such needs to be carefully reviewed.

As well as the total PHEEM score there are three sub-

scales: Perception of role autonomy; Perceptions of teaching;

and Perceptions of social support. Table 1 shows the items

within each sub-scale (negative items are italicized).

The postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment

329

Appendix 2: Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure

S. Roff et al.

330

The postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment

331

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Uptime Elements Passport: GineerDocument148 pagesUptime Elements Passport: GineerBrian Careel94% (16)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- ALCUCOA StandardsDocument21 pagesALCUCOA StandardsDennis Esik Maligaya100% (6)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sample CH 4 For Experimental ResearchDocument42 pagesSample CH 4 For Experimental ResearchDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- AREA V Entrepreneurship and EmployabilityDocument15 pagesAREA V Entrepreneurship and EmployabilityDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Service and Maintenance Manual AFPX 513 PDFDocument146 pagesService and Maintenance Manual AFPX 513 PDFManuel Amado Montoya AgudeloNo ratings yet

- Role of SupervisorDocument29 pagesRole of SupervisorDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Summary of RA 6713Document25 pagesSummary of RA 6713Dennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- A. Greenspan C. Panaciio D. Hesse 2.: Servant Leadership QuizDocument1 pageA. Greenspan C. Panaciio D. Hesse 2.: Servant Leadership QuizDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Given The Table Below, Fill Up The Columns Labeled Proportion and Percentage. ADocument9 pagesGiven The Table Below, Fill Up The Columns Labeled Proportion and Percentage. ADennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Statistics ExerciseDocument13 pagesStatistics ExerciseDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Financial Management SLCDocument56 pagesFinancial Management SLCDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Nature and Importance of Leadership, Traits and Characteristics of A LeaderDocument18 pagesNature and Importance of Leadership, Traits and Characteristics of A LeaderDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Power and Leadership JLCDocument21 pagesPower and Leadership JLCDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Supervisory Development: by Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDocument19 pagesSupervisory Development: by Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Logistics Supervision (Ps SLC) : Pssupt. Jesus B. Arceo (Ret) Ed.D., Ph. D. LecturerDocument83 pagesLogistics Supervision (Ps SLC) : Pssupt. Jesus B. Arceo (Ret) Ed.D., Ph. D. LecturerDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Records Management: (For PS SLC)Document59 pagesRecords Management: (For PS SLC)Dennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Management Process and EffectivenessDocument12 pagesManagement Process and EffectivenessDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Financial ManagementDocument40 pagesFinancial ManagementDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Govph: Duterte Orders Adoption of Cash Budgeting SystemDocument3 pagesGovph: Duterte Orders Adoption of Cash Budgeting SystemDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Salesmanship: A Form of Leadership: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDocument22 pagesSalesmanship: A Form of Leadership: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Power and Leadership and Leadership Actions TestDocument3 pagesPower and Leadership and Leadership Actions TestDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Leadership Actions: Dr. Dennis E. Maligaya V VN - 9Mu22Ius&Ab - Channel Bluet AlkDocument6 pagesLeadership Actions: Dr. Dennis E. Maligaya V VN - 9Mu22Ius&Ab - Channel Bluet AlkDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Area II FacultyDocument35 pagesArea II FacultyDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary 3 Sectors OnlyDocument4 pagesExecutive Summary 3 Sectors OnlyDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Batch 1 ProgrammeDocument15 pagesBatch 1 ProgrammeDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Accounting Presentation COUNTPADocument118 pagesAccounting Presentation COUNTPADennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- Financial Literacy: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDocument65 pagesFinancial Literacy: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDennis Esik MaligayaNo ratings yet

- 2023-Tutorial 02Document6 pages2023-Tutorial 02chyhyhyNo ratings yet

- Progressivism Sweeps The NationDocument4 pagesProgressivism Sweeps The NationZach WedelNo ratings yet

- 28Document12 pages28physicsdocsNo ratings yet

- Contents Serbo-Croatian GrammarDocument2 pagesContents Serbo-Croatian GrammarLeo VasilaNo ratings yet

- Brochure - Digital Banking - New DelhiDocument4 pagesBrochure - Digital Banking - New Delhiankitgarg13No ratings yet

- Exercise No.2Document4 pagesExercise No.2Jeane Mae BooNo ratings yet

- 1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Document99 pages1.quetta Master Plan RFP Draft1Munir HussainNo ratings yet

- Yukot,+houkelin 2505 11892735 Final+Paper+Group+41Document17 pagesYukot,+houkelin 2505 11892735 Final+Paper+Group+410191720003 ELIAS ANTONIO BELLO LEON ESTUDIANTE ACTIVONo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresDocument40 pagesChapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresTeltel BillenaNo ratings yet

- Robot MecanumDocument4 pagesRobot MecanumalienkanibalNo ratings yet

- Annexure 8: Medical Certificate (To Be Issued by A Registered Medical Practitioner) General ExpectationsDocument1 pageAnnexure 8: Medical Certificate (To Be Issued by A Registered Medical Practitioner) General ExpectationsMannepalli RamakrishnaNo ratings yet

- Daud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsDocument9 pagesDaud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsFatima Ismaeel33% (3)

- Win Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsDocument11 pagesWin Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsadetriyunitaNo ratings yet

- Simple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseDocument2 pagesSimple Future Tense & Future Continuous TenseFarris Ab RashidNo ratings yet

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiDocument6 pagesPaediatrica Indonesiana: Sumadiono, Cahya Dewi Satria, Nurul Mardhiah, Grace Iva SusantiharnizaNo ratings yet

- 2009 Annual Report - NSCBDocument54 pages2009 Annual Report - NSCBgracegganaNo ratings yet

- Need You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryDocument3 pagesNeed You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryAl UsadNo ratings yet

- Applied Nutrition: Nutritional Consideration in The Prevention and Management of Renal Disease - VIIDocument28 pagesApplied Nutrition: Nutritional Consideration in The Prevention and Management of Renal Disease - VIIHira KhanNo ratings yet

- KAHOOT - Assignment 4.1 Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesKAHOOT - Assignment 4.1 Lesson PlanJan ZimmermannNo ratings yet

- ESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 2014Document8 pagesESU Mauritius Newsletter Dec 2014Ashesh RamjeeawonNo ratings yet

- Approved Chemical ListDocument2 pagesApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- Viva QuestionsDocument3 pagesViva QuestionssanjayshekarncNo ratings yet

- ACCA Advanced Corporate Reporting 2005Document763 pagesACCA Advanced Corporate Reporting 2005Platonic100% (2)

- Prepositions French Worksheet For PracticeDocument37 pagesPrepositions French Worksheet For Practiceangelamonteiro100% (1)

- What Is Folate WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesWhat Is Folate WPS OfficeMerly Grael LigligenNo ratings yet

- Dispersion Compensation FibreDocument16 pagesDispersion Compensation FibreGyana Ranjan MatiNo ratings yet

- Sodium Borate: What Is Boron?Document2 pagesSodium Borate: What Is Boron?Gary WhiteNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Green Notes 2015Document34 pagesPublic International Law Green Notes 2015KrisLarr100% (1)