Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Interpersonal Relationships and Task Performance

Uploaded by

Corbean AlexandruCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Interpersonal Relationships and Task Performance

Uploaded by

Corbean AlexandruCopyright:

Available Formats

INTERPERSONAL RELATIONS AND GROUP PROCESSES

Interpersonal Relationships and Task Performance: An Examination of

Mediating Processes in Friendship and Acquaintance Groups

Karen A. Jehn

University of Pennsylvania

Priti Pradhan Shah

University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Campus

This study used multiple methods to examine group processes (information sharing, morale building,

planning, critical evaluation, commitment, monitoring, and cooperation) that mediate the effect of

relationship level on group performance. The study uses a 2 by 2 experimental design, crossing

relationship (friendship vs. acquaintance) as a between-subjects variable and task type (decision

making vs. motor) as a within-subject variable. Fifty-three 3-person groups participated in the study,

and data from 4 types of measurement were used to analyze the mediating processes between

relationship level and task performance. Friendship groups performed significantly better than ac-

quaintance groups on both decision-making and motor tasks because of a greater degree of group

commitment and cooperation. Critical evaluation and task monitoring also significantly increased

decision-making performance, whereas positive communication mediated the relationship between

friendship and motor task performance.

Friendship is often a consequence of teamwork. Prior relation-

ships, proximity, frequency of communication, and common

work goals are factors that facilitate friendship in work groups.

Research that investigated friendship at work has provided

mixed results regarding the benefits and detriments of friendship

on work performance. Despite the belief that friendship is an

impediment to productivity because it creates an increased so-

cial focus that detracts from the group's work goal (Bramel &

Friend, 1987; Homans, 1951), past studies suggest that friend-

ship (often operationalized as cohesion) in work groups may

have such benefits as information sharing, productive conflict,

and increased motivation (Berkowitz, 1954; Dailey, 1977; Ev-

Kai'en A. Jehn, Department of Management, University of Pennsylva-

nia; Priti Pradhan Shah, Strategic Management and Organization Depart-

ment, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities Campus.

This research was supported in part by grants from the Dispute Reso-

lution Research Center at Northwestern University; the University of

Minnesota, Twin Cities Campus; and the Reginald H. Jones Center for

Management Policy, Strategy, and Organization at the Wharton School

of the University of Pennsylvania. We are grateful to Maggie Neale,

Keith Weigelt, Craig Fox, and Jeanne Brett for their help and insightful

comments on the research project and the experimental design; to Tiffany

Galvin, Ha Ngyuen, and Ted Wong for their help in coding the process

data; to Mary Eileen Baltes for her editorial skills; and to Sara Yang,

Dave Polesky, and Emma Vas for their assistance in data entering and

analysis.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Karen

A. Jehn, Department of Management, Wharton School of the University

of Pennsylvania, 2000 Steinberg Hall-Dietrich Hall, Philadelphia, Penn-

sylvania 19104-6370. Electronic mail may be sent via the Internet to

jehnk@wharton.upenn.edu.

ans & Dion, 1991; Shah & Jehn, 1993). These contradictory

findings regarding relationships and group performance signify

a need for a more thorough examination of the processes in-

volved in friendship and acquaintance groups. We argue that

one can best conduct this investigation using multiple methods

and measurement techniques to examine underlying group

processes.

Although group performance studies have examined interper-

sonal relationship variables (operationalized as group affinity,

camaraderie, and cohesion), they have focused primarily on

outcomes and have neglected the group process (Evans & Dion,

1991). This focus on outcomes limits the investigation of group

processes, although questions about the impact of friendship

on group performance are important. Mediating processes are

critical to understanding the different behaviors and attitudes in

friendship and acquaintance groups that lead to performance

differences. Examining underlying group processes should pro-

vide a better understanding of performance differences in friend-

ship and acquaintance groups.

In this study, we investigated process differences among

friendship and acquaintance groups to determine whether and

why friendship among members is beneficial to group perfor-

mance. First, we integrate group and interpersonal relationship

literatures to provide an understanding of the differences be-

tween friendship and acquaintance groups. Then, we report on

our investigation of communication and behavior in two differ-

ent task situations (cognitive and motor tasks), considering that

group tasks often differ in the skills necessary for high-quality

performance (Gladstein, 1984; Jehn, 1995; Van de Ven & Ferry,

1980). Finally, we discuss general behaviors within friendship

and acquaintance groups that lead to performance differences

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997. Vol. 72, No. 4. 775-790

Copyright 1997 by the American Psychological Association. Die. 0022-3514/97/J3.00

775

776 JEHN AND SHAH

and the specific behaviors necessary for superior performance

on motor versus cognitive tasks in work groups.

To examine group processes, we proposed a multimethod

approach. Whereas most research has focused on a single me-

dium (for exceptions, see Weingart, 1992; Weldon, Jehn, &

Pradhan, 1991), a multimethod perspective is critical for under-

standing and triangulating the dynamics of psychological pro-

cesses. The use of multiple methods allowed us to more ade-

quately assess the influence of mediating processes and strength-

ened our understanding of the constructs under study. Constructs

are more accurate and reliable when there are multiple opera-

tional representations of each (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Thus,

we used four measurement methodologies: a postexperimental

questionnaire, content-analyzed audiotapes, behavior ratings of

videotapes, and objective measures of group behavior and

performance.

Friendship and Acquaintance Groups

The interpersonal relationship literature suggests that people

distinguish between friendship and acquaintance relationships

and that different rules govern people's interactions in the two

types of relationships (Clark & Mills, 1993; Clark, Mills, &

Powell, 1986; Greenberg, 1983; Pataki, Shapiro, & Clark,

1994). Friendship groups are defined as groups with close,

interpersonal ties and positive, amiable preexisting relationships

among members {Rawlins, 1983, 1989; Wright, 1984). The

friendships in these groups are voluntary, mutual, and often

communal in that members are concerned about each other's

welfare, regardless of benefits gained from the relationship

(Clark & Mills, 1979). The friendships are usually not ex-

change-based (i.e., members are not concerned with reciproca-

tion of benefits).

Acquaintance groups are defined as groups with limited fa-

miliarity and contact among members. Members may know each

other through casual encounters; however, a strong bond, past

history, and depth of mutual knowledge between the parties are

lacking. The interaction between acquaintances is not necessar-

ily voluntary or positive, as it is among friends. Although rela-

tionships exist on a continuum of intimacy, we followed previ-

ous research by focusing on two points (friendship and acquain-

tance) to assess group process differences (Pataki et al., 1994).

Group Process

Group process is defined as the behavior or interaction pat-

terns among group members (Steiner, 1972; Weldon & Weingart,

1988). Past research on process consultation, team develop-

ment, and T-group and sensitivity training has assumed that

improved interpersonal relationships among group members

lead to improved task performance (Guzzo & Shea, 1992).

These studies have focused on how interpersonal interactions

among group members reduce process loss. Process loss is the

extent to which group performance is inhibited by misunder-

standings, miscommunication, and dislike among group mem-

bers (Steiner, 1972). Process loss results in wasted group energy

and decreased productivity stemming from interpersonal diffi-

culties. Researchers have documented the dysfunctional effects

of mistrust, role ambiguity, and communication difficulties on

satisfaction in various task groups such as management teams,

airline crews, military combat units, mining crews, student

groups, and research and development teams (Hackman, 1991).

There is little evidence, however, to indicate that improving

interpersonal relationships increases work performance (Kap-

lan, 1979; Sundstrom, de Meuse, & Futrell, 1990; Woodman &

Sherwood, 1980).

In addition, past research on cohesiveness and performance

has yielded contradictory results (Evans & Dion, 1991; cf.

Guzzo & Dickson, 1996; Seashore, 1954). Although friendship

and cohesion are two separate constructs, they have numerous

commonalities and interdependencies. In particular, both focus

on interpersonal affinity among group members. We believe

that the interpersonal attraction that is the basis for friendship

facilitates cohesion in groups composed of friends. Thus, im-

portant insight into friendship groups can be gained by further

investigating past research on cohesion. Seashore's work sug-

gests that the relation between cohesion and group performance

is contingent on group norms. In highly cohesive groups, norms

for high and low performance elicited a high and low level of

performance, respectively. Although cohesion and friendship are

two separate constructs, both focus on interpersonal affinity

among group members. In a recent meta-analysis, Evans and

Dion (1991) found a strong positive correlation between cohe-

sion and performance. Because their analysis was conducted

only on published studies and were limited to laboratory groups

and sports teams, the authors were cautious in their interpreta-

tion. Evans and Dion also noted that the analysis of 26 unpub-

lished studies that were based on a larger sample revealed a

significant negative correlation. Thus, the direction of the rela-

tionship between cohesion and performance is still under debate.

We propose that examining the intervening processes between

relationship level (i.e., friendship vs. acquaintance) and perfor-

mance will provide a clearer understanding of the association

between the two variables.

Group processes needed for optimal performance also differ

depending on the type of task being performed (Jehn, 1995;

McGrath, 1984; Steiner, 1972). Processes that are optimal for

one task may be detrimental to another. For example, whereas

non-task-related conversation can serve as a distraction from

the tedium of a repetitive motor task, it may interfere with

the cognitive processes required for a complex decision-making

task. To investigate the intervening variables between friendship

and task performance, we focused in the present study on two

different tasks: a cognitive task (decision making) and a repeti-

tive motor task (model building). Cognitive tasks incorporate

conceptual skills and problem-solving abilities, whereas repeti-

tive motor tasks (e.g., a manufacturing or assembly-line task)

typically emphasize physical skills and speed. The motor task

we chose is a maximizing task, according to Steiner (1972),

because members were instructed to complete as many models

as possible in the time allowed. These two tasks differed funda-

mentally on the conceptual versus behavioral dimensions cited

by McGrath (1984) and were chosen because of the different

group processes they require for high-caliber performance

(Gladstein, 1984; Gruenfeld & Hollingshead, 1993; McGrath,

1984). We discuss the different group processes necessary for

high-caliber performance on these tasks in the next section.

FRIENDSHIP AND ACQUAINTANCE GROUPS 777

Interpersonal Relationships, Group Process,

and Task Performance

We provide empirical support that group processes related to

positive interpersonal relations improve group performance. We

examined seven processes (information sharing, planning, criti-

cal evaluation, morale-building communication, commitment,

monitoring, and cooperation) that we predicted would mediate

the association between relationship level and task performance

of work groups. We believed that we could better understand

the complexity of the relation between friendship and perfor-

mance and the contradictions in past research by examining

the interaction patterns in friendship and acquaintance groups.

Interactions with friends and interactions with acquaintances

are dramatically different, and their differences may affect task

performance (Shah & Jehn, 1993).

Information Sharing

A primary difference between friendship and acquaintance

groups is the amount and type of communication each generates.

Research has shown that individuals share more information

with friends than with nonfriends (Newcomb & Brady, 1982;

Newcomb, Brady, & Hartup, 1979; Zaccaro & Lowe, 1988).

We define information sharing in groups as making statements

to other group members about the task. Collective information

sharing includes disclosing factual, task-relevant information to

other group members (Henry, 1995; Stasser, 1992). Information

sharing also encompasses Bales's (1951) notion of task behav-

ior. Active task behavior includes offering opinions, suggestions,

and information; passive task behavior includes asking for infor-

mation, opinions, or suggestions. Talking about the task, ex-

pressing feelings and ideas, and freely exchanging task-related

thoughts are examples of information sharing.

Self-disclosure norms common among friends result in candid

and copious information exchange (Argyle & Furnham, 1983;

Hays, 1985). Network researchers (e.g., Albrecht & Ropp,

1984) have found that social relationships among workers pro-

vide the opportunity for more task-related exchanges. More in-

formation is shared because of greater contact and trust in

friendship relationships (Danowski, 1980; Rawlins, 1983; Ro-

loff, 1987); therefore, we proposed that:

Hypothesis la: Friendship groups share more information than ac-

quaintance groups.

Information sharing increases task-focused attention and ef-

fort, which in turn increase motor task performance (Weldon

et al., 1991). Motor task performance benefits from information

shared about unique skills and knowledge about the prescribed

way to perform the task. Group performance on cognitive tasks

also increases when members share task-relevant information

(Stasser & Stewart, 1992). Individuals often bring diverse infor-

mation and skills to a group. The unique information that each

member holds is called unshared information (Larson, Chris-

tensen, Abbott, & Franz, 1996; Stasser & Titus, 1985, 1987).

Groups who pool this unshared information increase the avail-

able informational resources. Small groups who engage in fact-

finding discussions increase performance by emphasizing im-

portant, unique information that members possess (Stasser,

1992). Increasing the sharing of diverse opinions and informa-

tion about task-related skills and strategies can enhance group

performance because valuable information necessary to com-

plete the task becomes salient to all group members (Larson et

al., 1996). Therefore, we predicted that:

Hypothesis 1b: Information sharing increases motor task

performance.

Hypothesis lc: Information sharing increases cognitive task

performance.

1

Planning

Planning is a specific type of task-related communication in

which group members formulate actions regarding time and

function that lead to specific goals (McGrath, 1984). Planning

entails specifying task procedures, delegating task responsibil-

ity, determining temporal order for task duties, and determining

actions necessary to complete the task (Weldon et al., 1991). We

investigated explicit in-process planning, that is, verbal planning

behavior that takes place while group members work on a task,

rather than planning that occurs before the start of a task

(Weingart, 1992). When group members discuss whether to

perform a certain act, how a certain act should be performed,

or who should perform a certain act, they are participating in

planning. The open channels of communication present in

friendship groups should facilitate planning, assuming that

group members are motivated to complete their task. We there-

fore hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2a: Friendship groups plan more than acquaintance

groups.

Research has shown that planning is positively related to

group performance (Dean & Sharfman, 1996; Weldon et al.,

1991). Planning influences performance effectiveness in two

ways: Group members can share past strategies and implement

them, or they can develop or adapt new plans (Hackman &

Morris, 1975). High-quality planning reduces coordination

problems, which hinder task performance, and increases the

likelihood that the group will uncover more efficient and effec-

tive plans (Smith, Locke, & Barry, 1990). Coordination, or the

integrating of individuals to accomplish a task (Van de Ven,

Delbecq, & Koenig, 1976), is necessary for effective collective

action. Planning allows group members to work together to

best distribute the work, to coordinate the actions of individual

members, and to open channels for members to share informa-

tion (Weingart & Weldon, 1991). Research has shown that

explicit discussions of strategy improve group productivity

(Hackman, Brousseau, & Weiss, 1976) when a task requires

coordination (e.g., a motor task) or sharing among members

(e.g., a cognitive task). We investigated tasks in which coordi-

nation is necessary, that is, tasks in which members are highly

interdependent and in which organization leads to improved task

1

Throughout this section, the " a " hypotheses always refer to the

relationship between friendship groups and the mediating process, the

" b " hypotheses refer to the relationship between the mediating process

and motor task performance, and the ' V ' hypotheses refer to the relation

between the mediating process and cognitive task performance.

778 JEHN AND SHAH

performance (Shure, Rogers, Larsen, & Tassone, 1962; Weldon

et al., 1991). Therefore, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 2b: Planning increases motor task performance.

Hypothesis 2c: Planning increases cognitive task performance.

Critical Evaluation

Critical evaluation occurs when one or more members finds

fault with or judges the quality of other group members. Dis-

agreements or arguments about the way a group member per-

forms her duty, criticism about a member's performance, or

disapproval of a member's suggestion are instances of critical

evaluation. Critical evaluation includes examining, judging, ana-

lyzing, evaluating, and scrutinizing another group member's

work.

Studies show that friends manage disagreements differently

than nonfriends (Aboud, 1989; Ladd & Emerson, 1984; Nel-

son & Aboud, 1985). Friends offer more explanations to their

partners, make more criticisms, and are more likely to get con-

firmatory information relative to nonfriends. Gottman and Park-

hurst (1980) provided evidence that individuals tolerate dis-

agreements with friends more than with nonfriends. The friends

in Gottman and Parkhurst's study tended to disagree and to

provide critical feedback in a constructive manner that the re-

ceiver perceived as positive and productive. The nonfriends,

however, were more likely to be perceived as making assump-

tions and providing neutral or negative evaluations on the basis

of flaws inherent in the person (e.g., flaws in abilities, knowl-

edge, and personality) rather than on circumstances external to

the person.

Preexisting personal relationships encourage group members

to critically evaluate each other's ideas. Knapp, Ellis, and Wil-

liams (1980) have asserted that friends are more likely than

nonfriends to give and receive both positive and negative feed-

back. Research has shown that criticism and conflict regarding

opinions and ideas are more common in close relationships than

in acquaintances (Argyle & Furnham, 1983). Roloff (1987)

suggested that a supportive environment established by preex-

isting friendships may foster the questioning and challenging of

ideas in a nonthreatening manner. Relational security reduces

the fear of retaliation or negative repercussions that result from

critical comments. In addition, critical evaluation may be sup-

pressed in acquaintance groups because norms of politeness

govern social interaction among strangers (Mikula & Schwinger,

1978). We therefore hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3a(l): Friendship groups engage in more critical evalu-

ation than acquaintance groups.

Alternatively, research on interpersonal relationships has sug-

gested that people may avoid conflict with friends in order to

maintain their relationships. Group members who are friends

are often preoccupied with maintaining their relationships and

therefore are unwilling to critically evaluate each other's views

(Kelley & Thibaut, 1979). Davidson and Duberman (1982)

found that participants in dyadic friendship groups experienced

fewer arguments than nonfriends. Threats to the relationship

often lead to restricted information exchange and processing

(Gladstein & Reilly, 1985). Similar values, viewpoints, and

experience among members will lead to similar task interpreta-

tions, thus reducing the likelihood of disagreements (Lincoln &

Miller, 1979; McPherson & Smith-Lovin, 1987). The cohesive-

ness of friendship groups makes them prone to "groupthink"

and consensus building (Janis, 1982). We acknowledge the

competing theories regarding the amount of critical evaluation

present in friendship groups because of the various norms and

psychological processes operating, and we have proposed com-

peting hypotheses. Therefore, in contrast to hypothesis 3a( l ) ,

we proposed that:

Hypothesis 3a(2): Acquaintance groups engage in more critical

evaluation than friendship groups.

Critical evaluation is an integral component in decision-mak-

ing tasks, for it enables a group to explore alternatives and make

informed decisions. Decision-making performance is improved

by analyzing and prioritizing options (Allison, 1971). Critical

evaluation can eliminate the negative impact of groupthink

(Janis, 1982) by questioning assumptions and increasing the

generation of acceptable alternatives (Cosier & Schwenk,

1990). In addition, dissent among members can produce diver-

gent views that enhance decision making (Nemeth, 1986). We

therefore hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3b: Critical evaluation improves cognitive task

performance.

Alternatively, critical evaluation can be a hindrance in groups

performing routine motor tasks. When procedures are set, the

criticism can interfere with efficient processing (Guzzo, 1986).

Differences of opinion and criticism can cause stress and irrita-

tion, which inhibit performance (Jehn, 1995). According to

Gladstein (1984), simple tasks do not require task discussion

or evaluation of strategies and may even be harmed by the

interference. Thus, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 3c: Critical evaluation decreases motor task

performance.

Morale-Building Communication

Communication in work groups involves both task-related

communication (e.g., information sharing, planning, and critical

evaluation) and non-task-related communication. A frequent

form of non-task-related communication is morale-building

communication (Weldon et al., 1991). Morale-building commu-

nication is defined as communication that encourages group

members to perform better by exchanging positive comments

about the group's or group member's performance. Offering

positive comments, exuding confidence, displaying a positive

attitude, providing words of encouragement, and showing enthu-

siasm are examples of morale-building communication.

Friendship groups often consist of homogeneous individuals

with similar interests who are more likely to engage in non-

task-related conversation (e.g., gossip) than are individuals in

acquaintance groups because of their common interests and ex-

periences (Davidson & Duberman, 1982; Lincoln & Miller,

1979; McPherson & Smith-Lovin, 1987). Positive affect and

admiration among friends are likely to result in morale-building

communication in task groups (Wright, 1984). Newcomb et al.

FRIENDSHIP AND ACQUAINTANCE GROUPS 779

(1979) found greater positive affective expression and recipro-

cal praise in friend interactions than in nonfriend interactions.

Friends also tend to be more "ego-supportive" of one another

than do nonfriends, which fosters positive, efficacious, encour-

aging communication among friendship group members (Raw-

lins, 1989). We therefore proposed that:

Hypothesis 4a: Friendship groups engage in more morale-building

communication than acquaintance groups.

An increased level of morale-building communication has

both positive and negative consequences, depending on the type

of group task. Morale-building communication (e.g., a pep talk)

provides a sense of efficacy among group members, arouses

their emotions, and thus induces groups to work faster on a

repetitive motor task (Bandura, 1982; Bandura, Reese, & Ad-

ams, 1982; Thorns, Moore, & Scott, 1996). Morale-building

communication also influences performance by increasing group

members' effort (Weldon & Weingart, 1988). Thus, we hypoth-

esized that:

Hypothesis 4b: Morale-building communication increases motor

task performance.

However, these same morale-building behaviors may interfere

with cognitive task performance. Because the quality, rather than

the speed, of the decision is the important factor in decision-

making task performance, the emotional arousal provided by

morale-building communication may not be necessary. In fact,

self-efficacy and overconfidence can cause individuals to invest

too little in cognitive tasks (Bandura, 1982; Fischhoff, Slovic, &

Lichtenstein, 1977). Similarly, non-task-related communica-

tion, which creates an amiable working environment in routine

tasks, may interfere with the added attentional demands of a

decision-making task. In a study of decision-making tasks

(Shah & Jehn, 1993), highly emotional exchanges (both posi-

tive and negative) detracted from the concentration of group

members. Another negative factor that influences performance

of cognitive tasks, especially prevalent in friendship groups, is

the tendency of group members to socialize rather than focus

on the task. The cognitive effort applied to non-task-related

discussion involves cognitive resources necessary for effective

decision making. Additionally, open communication and self-

disclosure can have negative effects, causing interpersonal prob-

lems that inhibit productivity (Jehn, 1995; Rawlins, 1983). On

the basis of our reasoning, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 4c: Morale-building communication decreases cogni-

tive task performance.

Commitment

Commitment to the work group is defined as the strength

of a member's identification and involvement with the group

(Mowday, Porter, & Steers, 1982). O'Reilly and Chatman's

(1986) analysis of organizational commitment revealed identi-

fication as a basis for attachment to an organization, because

members desire affiliation with the group. Committed group

members feel obligated to the group, identify with the group,

are dedicated to the other members, and have emotional ties to

the group.

The level of commitment to the group is expected to be higher

in friendship groups than in acquaintance groups because mem-

bers have strong interpersonal ties. Friends focus on the group

as an entity and define their identity as part of the group. The

emotional attachment present within friendship groups also in-

creases commitment (Brass, 1984). Thus we proposed that:

Hypothesis 5a: Friendship groups have a higher level of commit-

ment than acquaintance groups.

Commitment to the work group causes group members to

increase their task effort, regardless of the type of task being

performed (Newcomb & Brady, 1982; Whitney, 1994). Ac-

cording to Klein and Mulvey (1995), commitment to and iden-

tity with the group encourages members to perform well. Iden-

tity with the group encourages members to work harder to pro-

tect their group and individual identity (Cialdini et al., 1976;

Tesser, Millar, & Moore, 1988); this, in turn, enhances perfor-

mance. Research conducted with groups who performed routine

motor tasks demonstrated that high levels of commitment in-

crease group performance (Jehn, 1995; Weldon et al., 1991).

Similarly, groups who perform cognitive, nonroutine tasks have

higher levels of performance when group members are highly

committed to the group (Jehn, 1995; O'Reilly & Caldwell,

1981). Thus, we predicted that:

Hypothesis 5b: Commitment increases motor task performance.

Hypothesis 5c: Commitment increases cognitive task performance.

Task Monitoring

Task monitoring is an administrative step group members take

to ensure that the task is completed on time or at all. Task

monitoring takes place when members assess their performance

progress and the likelihood they will reach their goal (Weldon

et al., 1991). For example, for a group with a specific deadline,

monitoring behavior includes checking the clock for the time

remaining to complete the task and assessing the amount of

work remaining.

Attachments within friendship groups as well as group ac-

countability and reputation effects cause members to monitor

their behavior to ensure success. Group members who identify

with the group and are concerned about reputation effects are

more likely to perform the monitoring function (Robinson &

Weldon, 1993). Members who are not strongly concerned about

the group or identified with the group tend to monitor less. We

therefore proposed that:

Hypothesis 6a: Friendship groups engage in more monitoring be-

havior than acquaintance groups.

Research shows that monitoring behavior in groups is posi-

tively related to group performance (Weldon et al., 1991). Task

monitoring entails assessing the group's performance on the

basis of the time remaining and the group's rate of production.

Monitoring enables members to update their level of effort and

to identify when different strategies are necessary to increase

performance (Robinson & Weldon, 1993). Seeking feedback

about the task through monitoring also improves problem solv-

ing and strategy development in that members assess current

780 JEHN AND SHAH

strategies and reevaluate the process (Ashford & Cummings,

1983). Therefore, we proposed that changes made by monitor-

ing would increase group performance on both motor and cogni-

tive tasks:

Hypothesis 6b: Task monitoring increases motor task performance.

Hypothesis 6c: Task monitoring increases cognitive task

performance.

Cooperation

Cooperation "aids the performance of another group member

or contributes to the ease with which group members coordinate

their efforts" (Weldon & Weingart, 1988, p. 22). Cooperation

includes members' helping one another with tasks (e.g., handing

each other materials) and partaking in mutually beneficial be-

havior (e.g., trading tasks so that members are more suited to

their tasks).

We propose that cooperation is greater in friendship groups

than in acquaintance groups because of differences in social

exchanges, such as helping behavior and task support. Mutual

assistance, or the assumption that individuals can count on one

another in times of need, is a characteristic of friendships (Ar-

gyle & Furnham, 1983; Davis & Todd, 1982). Whereas norms

of equity govern exchange among strangers (Clark & Mills,

1979), equality or need norms are more common among close

friends (Austin, 1980; Clark & Reis, 1988). Therefore, friends

provide assistance to each other on the basis of needs and de-

sires; strangers or acquaintances do so to reciprocate past bene-

fits or to obtain future reciprocity. Given the open flow of infor-

mation in close relationships (Roloff, 1987), individuals are

more aware of their friends' needs and therefore are better able

to provide assistance. Because of obligations, a cooperative ori-

entation, and role expectations inherent in relationships, friends

are more likely to pay attention to and fulfill others' needs

(Clark, Mills, & Corcoran, 1989; Newcomb et al., 1979). Indi-

viduals also feel better after helping a friend (Williamson &

Clark, 1992) and are more likely to seek assistance from friends

(Harlow & Cantor, 1995; Roloff, Janiszewski, McGrath,

Burns, & Manrai, 1988). We therefore proposed that:

Hypothesis 7a: Friendship groups cooperate more than acquain-

tance groups.

Cooperation among members is a necessary component of

superior task performance (Newcomb & Brady, 1982; Whitney,

1994). Group members who help each other on a task can

increase their effort and rate of production (Hackman, 1987).

Cooperative groups members share information, pay attention

to others, have few communication difficulties, and thus perform

better when working on interdependent tasks (Weldon & Wein-

gart, 1988). Therefore we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 7b: Cooperation increases motor task performance.

Hypothesis 7c: Cooperation increases cognitive task performance.

In sum, we hypothesized that friendship groups would engage

in more information sharing, planning, morale-building commu-

nication, task monitoring, and cooperation and would have

higher levels of commitment than acquaintance groups. We pro-

posed competing hypotheses for the likelihood of critical evalua-

tion in friendship and acquaintance groups on the basis of past

research. We hypothesized, in turn, that performance on the

motor task would be positively associated with information shar-

ing, planning, morale building, commitment, task monitoring,

and cooperation and would be negatively associated with critical

evaluation. In contrast, we hypothesized that performance on the

cognitive task would be positively associated with information

sharing, planning, critical evaluation, commitment, task moni-

toring, and cooperation and would be negatively associated with

morale-building communication. Overall, we suggested that

friendship groups would engage in group processes that enhance

performance on both motor and cognitive tasks. Thus, our final

overall prediction was the following:

Hypothesis 8: Friendship groups perform better on motor and cog-

nitive tasks than acquaintance groups.

Method

Participants

One hundred fifty-nine business students (53 three-person groups)

participated in the study. Participants were on average 28.21 years old,

worked 40.7 hr a week, and were primarily full-time employees. Thirty-

eight percent of the participants were female.

Procedure

The study used a 2 by 2 experimental design, crossing relationship

(friendship vs. acquaintance) as a between-subjects variable and task

type (cognitive vs. motor) as a within-subject variable. Each group

performed two tasks, cognitive and motor, and completed postexperi-

mental surveys. Task order was counterbalanced. Groups were video-

taped during both tasks.

Participants were assigned to groups on the basis of a class survey

administered 1 week prior to the experimental date, which asked them

to identify up to 10 classmates with whom they were friends and had a

"close interpersonal relationship." Students who listed each other on

this survey were placed in friendship groups. To match our definition

of friendship, all 3 members must have had mutually reciprocated ties.

This means a participant was placed in a friendship group only if he or

she had mutually named both of the other members as close personal

friends and was named by the other 2 as a close personal friend. The

listing of a friend had to be voluntary and reciprocated by the person

named. Those who did not list each other were placed in acquaintance

groups (cf. Pataki et al., 1994). The acquaintance groups were therefore

composed of 3 members who had not mentioned each other on their

lists. There were 78 participants in 26 groups in the friendship condition

and 81 participants in 27 groups in the acquaintance condition.

The number of people required to complete the task, task interdepen-

dence, and task division were controlled across task types. The cognitive

task we used was a scorable task that required problem-solving skills

(Stasser, Taylor, & Hanna, 1989). Having a scorable task allowed us to

compare across groups. Groups were given six completed master of

business administration applications and had 30 min to rank the appli-

cants on six criteria (academic abilities, interpersonal skills, focus, moti-

vation, career progress, and outside activities) and to make final accept,

wait-list, or reject decisions. Groups were asked to match admissions

committee decisions for each applicant (i.e., if a group chose "accept"

for Applicant 1 and the admissions committee had chosen "accept" for

Applicant 1, this equaled one match). Groups were not told how many

of the six should be accepted, wait-listed, or rejected.

FRIENDSHIP AND ACQUAINTANCE GROUPS 781

The motor task we used was a model-building task that required

routine, repetitive manual labor. Participants were given supplies (Styro-

foam balls, glue, Popsicle sticks, aluminum foil, macaroni, string, and

Tinker Toys) and were told to build models that matched a given diagram

(see Weldon et al., 1991, or Weingart, 1992, for task details). They

then built one structure in order to become familiar with the task. The

experimenter checked the model to verify that it matched the diagram

and gave the members feedback regarding deviations from the diagram.

The experimenter then set a timer, which was visible to group members,

told them to begin, and left the room. Groups had two 10-min sessions

and were told their performance would be measured by the number of

models completed in each session. To avoid arbitrary goal setting, we

told groups that most groups who had performed this task completed

eight models per session. Participants were later debriefed. Prior use of

this motor task with similar participants indicated that this was a difficult

goal (Weldon et al., 1991).

Process Analysis

We used four types of data measurement to analyze the mediating

group processes between relationship level and task performance: a

postexperi mental questionnaire, content-analyzed audiotapes, behavioral

ratings of videotapes, and objective measures of individual actions (i.e.,

number of applications scanned and number of times a member looked

at the timer). The perceptual and behavioral measures provided direct

and unobtrusive measures of group process. The postexperimental ques-

tionnaire provided self-report responses from the participants, the con-

tent analysis provided measures of verbal communication, and the behav-

ioral ratings provided measures that focused on nonverbal actions, as

did the objective measures of action frequencies taken from the video-

tapes. We performed triangulation of multiple operationalizations to ex-

amine the mediating process that influenced group performance in

friendship and acquaintance groups, which provided a rigorous examina-

tion of group processes.

Content-analyzed audiotapes. We used a three-step process to ana-

lyze the content of group discussions. First, tapes were transcribed by

an individual unaware of the hypotheses. To check for accuracy, we

randomly selected segments from one third of the audiotapes and com-

pared them with the transcripts. The results indicated that the discussions

were accurately transcribed. Second, each transcript was separated into

thought units. A thought unit is defined as a "sequence of a few words

conveying a single thought" (Weldon et al., 1991, p. 559) and was

deemed the appropriate unit for analysis of meaning. Two coders unitized

the transcripts; both were blind to condition and one was blind to the

hypotheses. Fifteen of the 53 transcripts were unitized by both coders;

the others were unitized by one coder. To determine reliability between

the coders, we calculated the percentage of disagreement for the 15

transcripts that were unitized by both coders. The results indicated that

die coders disagreed on unitizing once for every 100 units. Specific

guidelines for unitizing can be found in the Appendix.

Third, raters were trained to classify thought units into eight different

categories: information sharing, planning, critical evaluation, morale

building, monitoring, commitment, cooperation, and uncodable units

(which accounted for fewer than 1% of all thought units, often because

of poor tape quality or mumbling). Information sharing units included

statements about basic information needed to complete the task (e.g.,

"There are six applications"; "We can accept as many as we want";

and "We have red, yellow, and green sticks"). Planning units included

phrases about how acts should be performed, who should do what, and

in what order acts should be performed (e.g., "I' ll do the bases and

you can do the gluing"; "First let's all read everything through one

time"; and "What should I do first?"). Critical evaluation units in-

cluded statements such as "I think you did that wrong"; "I don't agree

with your decision"; and "That model looks awful!" Morale-building

units included phrases such as "No problem, we can do it!" and "Okay,

we're doing great!" Monitoring was measured by the extent to which

group members asked, "How many do we have done now?" or "We

have two minutes left." The level of cooperation in each group was

determined by the number of times members asked for or offered help

or reinforced the common interest of the group (e.g., "Can you hand

me that application?" and "We have to work as a team here"). State-

ments about group commitment included ' 'I really feel like a part of

this group" and "I' m certainly committed to us."

Three different raters coded transcripts. All three raters were unaware

of condition, and two raters were unaware of the hypotheses. Twenty-

one of the 53 transcripts were coded by two of the raters; the others

were coded by one rater, once the rate of agreement between all pairs

of raters was over 90%. Interrater agreement between the raters was

based on the 21 transcripts coded by two of the raters. Kappa, a conserva-

tive measure of agreement, was used to determine interrater agreement

(Brennan & Prediger, 1981). The average kappa was 96.0%. The cate-

gory-specific kappas were the following: for information sharing,

88.9%; for planning, 91.1%; for critical evaluation, 99.4%; for morale

building, 99.5%; for monitoring, 97.0%; for commitment, 97.8%; for

cooperation, 97.3%; and for uncodable units, 97.2%. Kappa was calcu-

lated by calculating the number of times that the judges agreed on the

category in which to place a unit, dividing by the number of units in

the transcript, and adjusting for chance.

2

A complete description of the

eight categories, categorization guidelines, and category-specific reli-

abilities is provided in the Appendix.

Frequencies of behaviors. All acts performed by each member (e.g.,

wrapping foil around a ball, attaching a green base, moving a box,

picking up an application, giving the application to a group member)

were recorded from the videotapes by a research assistant who was

unaware of the hypotheses. The acts performed by each group member

were used to assess the amount of morale-building communication, mon-

itoring, and cooperative acts. Morale-building acts consisted of high-

fives, clapping, and backslapping as acts of encouragement among mem-

bers. Monitoring was measured by the number of times group members

looked at or pointed to the timer. The level of cooperation in each group

was determined by the number of times members helped one another

(e.g., by pointing to information on an application or handing the appli-

cation to another member in the application task, or by passing materials

or assisting in attaching materials to the final structure in the model-

building task). These behaviors indicated cooperation among members

to complete the task. To check the accuracy of the listings, 15 one-

minute segments were viewed by the experimenters. The category-spe-

cific kappas for these categories were the following; for morale-building,

100%; for monitoring, 98%; and for cooperation, 98%.

Videotape ratings. The videotapes were also rated by two raters

unaware of the hypotheses. The two raters watched each group's video-

tape four times for both the model-building task and the decision-making

task. They rated the actions of each individual and the interaction among

group members for each task on information sharing, planning, critical

evaluation, morale-building communication, commitment, monitoring,

and cooperation. Raters were given definitions of the process variables

and were asked about statements such as ' 'This group engaged in a lot

2

Although a sound track was present on the videotapes, we chose to

code the verbal behaviors from the audiotapes for two reasons. First,

the clarity of the sounds on the audiotape was superior to that on the

videotape. Second, our coding scheme used the thought unit as the unit

of analysis and was more accurate when we used a hard copy of the

transcripts from the audiotapes than when we listened directly to the

sound from the videotapes. We realize that by coding only the transcripts,

we were unable to capture the nonverbal behaviors associated with the

verbal behavior; however, we expected to capture much of the nonverbal

behavior in the videotape ratings.

782 JEHN AND SHAH

of planning" and "This group engaged in a lot of task monitoring."

They rated the behaviors on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree). The average interrater agreement was 89.3%, ranging

from 85.5% (for planning) to 96% (for cooperation). When raters rated

an item farther than 1 point apart, they discussed the item and behavior

until they reached agreement. A complete description of the eight catego-

ries and items is provided in the Appendix.

Postexperimental questionnaire. Self-reports of information shar-

ing, morale-building communication, planning, critical evaluation, com-

mitment, and cooperation were collected after the model-building task

and the decision-making task. For example, commitment was measured

by the members' ratings of the following questions: "I was very commit-

ted to this work group

1

'; "I would talk up this work group to my friends

as a great group"; and "I would be proud to tell others that I am part

of this work group." Group members responded to the items on 7-point

scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The items that measure

each variable in the model are included in Table 1.

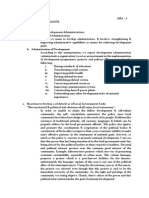

Scale development. Scales were developed from the four methods

of construct measurement (postexperimental questionnaire, content-ana-

lyzed audiotapes, behavioral ratings of the videotapes, and action fre-

quencies) for the seven mediating variables (information sharing, plan-

ning, critical evaluation, morale-building communication, commitment,

monitoring, and cooperation). We performed a principal-components

analysis using an oblique rotation. The results are provided in Table 1.

An oblique rotation was performed to take into account the intercorrela-

tion of the process variables (Kim & Mueller, 1978). A six-component

solution was found, on the basis of the scree test and eigenvalues

above 1.0.

The first component included four items that measured morale-build-

ing communication: the transcript rating of morale building, two items

from the video ratings, and one item from the pnstexperimental question-

naire. Two items were reverse-coded to reflect positive morale building.

Also loading on Factor 1 were three items that reflected information

sharing: the content-analyzed transcript rating of information sharing,

the video rating of open communication, and one item from the postex-

perimental questionnaire. We labeled this factor Positive Communication

and used it to test our hypotheses regarding morale-building communica-

tion and information sharing. The Cronbach alpha for Positive Communi-

cation was .86.

Cooperation was reflected in the second component by three items of

the video raters ("This member was very cooperative"; "This member

engaged in a lot of help-offering behavior"; and "This member put

forth a lot of effort"); the number of actions regarding cooperation

tallied from the videotapes (e.g., handing, passing, and answering ques-

tions); and one item from the postexperimental questionnaire ("How

cooperative and helpful were your group members?''). The Cronbach

alpha for Factor 2, Cooperation, was .79.

The third component included the six items that measured critical

evaluation: three items from the postexperimental questionnaire ("How

often did people in your work group disagree about opinions regarding

the work being done?" "To what extent were there differences of opin-

ion in your work group?" and "How frequently did you have disagree-

ments about the work you did with other people in your work group?");

the critical evaluation component of the content-analyzed audiotapes;

and two items from the video ratings (e.g., "This group engaged in a

lot of critical evaluation" and "This group engaged in a lot of conflicts

about ideas"). The Cronbach alpha was .88 for Critical Evaluation,

Factor 3.

The fourth component reflected the monitoring behavior of the group

members. The behavioral ratings from the videotapes ("This group

engaged in a lot of task monitoring'') and the content-analyzed audiotape

comments regarding monitoring comments (e.g., "How many do we

have done?" and "How much time is left?") loaded on this component.

The Cronbach alpha for Factor 4, Monitoring, was .98.

The fifth component included two postexperimental questionnaire

items that reflected commitment to the group ("I was very committed

to this work group' ' and ' '1 would talk up this work group to my friends

as a great group") and the videotape ratings of commitment ("This

group was very committed to each other" and "This member was very

committed to doing wel l "). The Cronbach alpha for Factor 5, Commit-

ment, was .82.

Planning was the sixth component and included the behavioral video

rating ("This member engaged in a lot of planning") and one item

from the postexperimental questionnaire ("How much disagreement is

there about procedures in your work group?"). The Cronbach alpha

was .71 for Planning, Factor 6. The intercorrelations among the factors

ranged from .02 (for Critical Evaluation and Planning) to ,36 (for Com-

mitment and Cooperation) with an average of .18.

The principal-components analysis and Cronbach alphas indicate that

there is consistency across methods of measurement and that triangula-

tion of multiple methods is an appropriate and robust way to examine the

mediating processes between relationship level and group performance.

We averaged the 13 individual-level items to produce composite scores

on each variable for each group member. We then averaged these scores

across groups to produce group scores of the factors. We performed the

eta-squared test for aggregation to determine whether any two people

within the same group were more similar than two people from different

groups. The results exceeded .20 for all factors, indicating that it was

appropriate to aggregate the factors to the group level (Georgopoulos,

1986, p. 40).

Performance measures. Motor task performance scores were based

on the number of models produced. Cognitive task performance was

calculated as the degree to which group decisions matched the admis-

sions committee decisions. Comparison with experts' performance is a

common way to assess group performance (McGrath, 1984). Cognitive

task performance scores were therefore based on the number of times

group decisions matched those of the admissions committee.

Results

Manipulation Checks

As shown by / tests, participants in the acquaintance groups

were significantly less likely to rate other group members as

friends on the postexperimental questionnaire, M = 3.73 (SD

= 1.47), with 1 strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree,

than were participants in friendship groups when responding to

the item "The other people in this group are my friends," M

= 5.45 (SD = ].10),/(158) = 11.38,p < .0001, thus indicating

that groups were properly created. The members of friendship

groups were also significantly more familiar with one another,

M = 4.62 (SD = 1.37), were more cohesive, M = 5.74 (SD =

1.26), were more positive regarding interpersonal relations, M

= 4.36 (SD = 1.17), were more amiable, M = 6.25 (SD =

0.84), had more knowledge about one another's strengths and

weaknesses, M = 3.59 (SD = 1.75), and were more concerned

with maintaining their relationships, M = 5.12 (SD = 1.50)

than were members of the acquaintance groups: familiar M =

2.36 (SD = 1.25), with 1 = did not know others and 7 = knew

others very well, r(l 58) = 14.90, p < .0001; cohesive M =

4.68 (SD - 1.60), with 1 = not at all cohesive and 7 = very

cohesive, t( 158) - 6.37, p < .0001; positive M = 3.75 (SD =

1.15), with 1 = not at all satisfied and 7 very satisfied,

r(l 58) - 3.90, p < .0001; amiable M = 5.43 (SD = 1.26),

with 1 = don't like at all and 7 = like very much, f(158)

6.53, p < .0001; knowledge M = 1.97 (SD = 1.31), with 1 -

FRIENDSHIP AND ACQUAINTANCE GROUPS 783

Table 1

Factor Loadings for Group Process Measures

Measure

Factor 1 Factor 3

(Positive Factor 2 (Critical Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6

Communication) (Cooperation) Evaluation) (Monitoring) (Commitment) (Planning)

"It is easy to talk openly to all members of this group."

(PQ) .747

"This group engaged in very open communication." (VR) .738

Content analysis of information sharing (AT) .758

Content analysis of morale building (AT) .566

"People were angry about working in this group." (VR) .577

"This group engaged in a lot of morale building." (VR) .629

"I felt a lot of tension in this group." (PQ) .527

' 'How cooperative and helpful were your group

members?" (PQ) .048

Cooperative behaviorhanding, passing, answering

questions (AF) .216

"This member engaged in a lot of help-offering

behavior." (VR) .424

"This member was very cooperative." (VR) .347

"This member put forth a lot of effort." (VR) .408

"How often did people in your work group disagree about

opinions regarding the work being done?" (PQ) -. 293

' 'To what extent were there differences of opinion in your

work group?" (PQ) -. 376

' 'How frequently did you have disagreements about the

work you did with other people in your work group?"

(PQ) -. 367

Content analysis of critical evaluation (AT) .284

"This group engaged in a lot of critical evaluation." (VR) .067

"This group engaged in a lot of conflicts about ideas."

(VR) -. 108

"This group engaged in a lot of task monitoring." (VR) .065

Content analysis of task monitoring (AT) .071

"I was very committed to this group." (PQ) .230

"I would talk up this work group to my friends as a great

group." (PQ) .282

"This group was very committed to each other." (VR) .092

"This member was very committed to doing well." (VR) .022

"This group engaged in a lot of planning." (VR) .097

"How much disagreement is there about procedures in

your work group?" (PQ) .048

Content analysis of planning (AT) -. 276

Monitoring behaviorcheck time, check quality. (AF) .045

"I would be proud to tell others that I am part of this

workgroup." (PQ) .092

Content analysis of commitment (AT) .155

"To what extent did you talk about who would do

what?" (PQ) -. 068

"There was a lot of emotional conflict in this group."

(PQ) -. 345

"We engage in very open communication." (PQ) .201

Morale-building behaviorhigh-fives, clapping (AF) .116

Content analysis of cooperation (AT) .001

"How cooperative were you with your group members?"

(PQ) .161

Eigenvalues 7.21

-. 070

-. 030

-. 233

.214

.367

.316

.425

.815

.760

.619

.600

.708

.406

.300

.359

.244

.329

.403

.246

.301

-. 104

-. 101

-. 005

.406

.121

.234

-. 100

-. 235

.130

-. 104

.064

.201

.115

.098

.218

.191

6.14

.263

.289

.204

.113

.147

.228

.138

.166

.039

-. 306

-. 323

-. 272

.446

.501

.510

.537

.581

.530

.088

.087

.145

.375

.451

-. 296

.008

.036

.267

.098

-. 249

.145

.140

.114

.104

.244

.166

.125

3.11

-. 043

-. 075

-. 076

-. 020

-. 206

-. 028

-. 084

.124

.198

-. 078

-. 093

-. 190

-. 256

-. 152

.034

.038

-. 136

-. 125

.759

.764

.054

-. 076

-. 006

-. 205

--165

.198

-. 152

.137

-. 205

.054

-. 106

-. 020

.098

.249

.124

.044

1.69

.080

.071

.080

.302

.263

.279

.275

.042

-.062

.154

.096

-.060

.009

.069

.248

.181

-.235

.285

-.006

-.015

.557

.619

.760

.816

.145

-.067

.069

.229

.230

.230

.291

.303

-.259

.298

.042

.053

1.54

-. 081

-. 079

-. 027

.334

.011

.038

-. 175

.098

.391

.395

-. 303

-. 023

.079

-. 059

.126

.027

.030

.009

-. 074

-. 076

.188

.008

.098

.097

.536

.679

-. 059

.341

-. 022

.189

.175

.334

-. 295

.023

.098

.228

1.18

Note. N = 159. Boldface is used to indicate significant loading. AF = action frequencies; AT = audio transcripts; PQ = postexperimental

questionnaire; VR = video ratings.

not at all familiar with strengths and weaknesses and 7 = very

familiar with strengths and weaknesses, f(158) = 9.02, p <

.0001; contact M = 4.23 (SD = 1.59), with 1 = no concern

with contact to maintain the relationship and 7 = very con-

cerned with contact to maintain the relationship, t( 158) = 4.98,

p < .0001.

In addition, in the video ratings the friendship groups were

viewed as more concerned with the relationship, M = 3.75 (SD

- 1.12), more cohesive, M = 4.39 (SD = 1.28), and more

satisfied, M = 5.72 (SD = 1.32), than were the acquaintance

groups: relationship concern M = 3.24 (SD = 1.02), t(52) =

3.48, p< .001; cohesive M= 3.87 (SD = 1.14), 1(52) = 3.18,

784 JEHN AND SHAH

Table 2

Means and Standard Deviations by Relationship and Task

Process

Positive

communication Planning

Critical

evaluation Commitment Monitoring Cooperation

Task

performance

Group

Friendship

Acquaintance

Friendship

Acquaintance

Friendship

Acquaintance

M

4.28

3.87

4.16

3.87

4.22

3.87

SD

0.61

0.39

0.52

0.57

0.61

0.43

M

3.50

2.72

3.33

2.63

3.42

2.68

SD

1.72

1.55

1.64

1.36

1.68

1.45

M

1.56

1.78

2.35

2.24

1.96

2.01

SD M

Motor task

0.48 5.23

0.76 4.56

Cognitive task

0.91 5.03

0.98 4.19

Overall

0.91 5.13

0.90 4.37

SD

0.88

1.03

1.00

1.08

1.06

0.96

M

2.71

2.70

2.96

2.81

2.84

2.76

SD

1.77

1.79

1.81

1.74

1.75

1.76

M

5.06

4.76

4.70

4.11

4.88

4.44

SD

1.09

1.16

1.25

1.12

1.18

1.18

M

9.00

2.45

3.10

2.44

SD

3.98

1.28

1.07

1.26

Note. For friendship group, n = 26; for acquaintance group, n = 27.

p < .001; satisfied M= 5.37 (SD = 1.40), t(52) = 2.14, p <

.03. Friends also made more cohesive statements, M = 5.36 (SD

= 1.51), such as "We are such a close group" and "Together

forever!" than acquaintances, M = 4.43 (SD = 1.72), t(52) -

4.97, p < .001, as rated by the audio transcript raters.

Items regarding task attributes on the postexperimental survey

indicated that the tasks differed only on the cognitive and motor

dimensions; no significant differences were reported on task

interdependence, difficulty, challenge, effort expended, or goal

commitment. Significant differences were reported on the extent

to which tasks were repetitive: motor task M 6.04 (SD =

1.31), decision t askM = 3.34 (SD = 1.69), with 1 - not at

all repetitive and 7 = very repetitive, f(307) = 15.51, p < .001;

whether they required cognitive ability: motor task M = 3.50

(SD = 1.23), decision task M = 5.98 (SD - 1.19), with 1 -

no cognitive ability required and 7 = much cognitive ability

required, C(307) = 10.52, p < .001; and whether they required

physical labor: motor task M = 5.60 (SD = 1.49), decision

taskM = 1.62 (SD .97), with 1 = no physical labor required

and 7 = much physical labor required, r(307) = 27.57, p <

.001.

Hypotheses Tests

The means by relationship level and task type are shown in

Table 2. The number of models produced by a group during the

motor task ranged from 1 to 12. The number of correct decisions

made by a group (calculated by the degree to which group

decisions matched the admissions committee decisions) ranged

from 0 to 6. Table 3 provides the intercorrelations for all vari-

ables in the model.

Relationship level and group process. The overall multivari-

ate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for relationship was sig-

nificant, F( l , 52) = 6.73, p < .001. Thus, we conducted task

by relationship analyses of variance (ANOV\s) to test main

effects regarding relationship level and group processes. The

performance scores were normalized by task and combined for

each group. The main effect of relationship on performance

was significant, F(l, 52) 10.45, p < .01, thus supporting

Hypothesis S, that friendship groups perform better than ac-

quaintance groups. Further analysis using t tests indicated that

friendship groups produced significantly more models, M =

9.00 (SD = 3.98), than acquaintance groups, M = 2.45 (SD =

1.28), r(52) = 2.43, p < .05. Friendship groups also matched

more admissions committee decisions, M = 3.10 (SD = 1.07),

than acquaintance groups, M 2.44 (SD = 1.26), ?(52) =

2.30, p < .05.

The results of the ANOVAs indicate main effects for relation-

ship on positive communication, commitment, and cooperation.

Friendship groups exchanged more positive communication, M

= 4.22 (SD = .61), than acquaintance groups, M = 3.87 (SD

= .43), F(l, 52) = 6.87, p < .001, providing some support

for the hypotheses that friendship groups share more information

(as we predicted in Hypothesis l a) and exchange more positive

morale-building communication (as predicted in Hypothesis

4a). Hypothesis 5 a, that friendship groups have a higher level

of commitment than acquaintance groups, was supported:

Friendship groups were more committed, M = 5.13 (SD =

1.06), than acquaintance groups, M = 4.37 (SD - .96), F(l,

52) = 7.38, p < .001. Hypothesis 7a, that friendship groups

cooperate more than acquaintance groups, was also supported:

Friendship groups were more cooperative, M 4.88 (SD =

1.18), than acquaintance groups, M = 4.44 (SD = 1.18), F(\,

52) = 10.46, p < .01. There was no main effect for relationship

on planning, critical evaluation, or monitoring, contrary to

Hypotheses 2a, 3a, and 6a, respectively.

Group processes and task performance. Table 4 illustrates

the regression results examining the relation between perfor-

mance and positive communication, commitment, monitoring,

planning, and cooperation, regardless of the task performed.

Hypotheses 5b (motor task) and 5c (cognitive task) were sup-

FRIENDSHIP AND ACQUAINTANCE GROUPS 785

Table 3

Correlations Between Variables Across Friendship and Age Groups

Variable 1

1. Critical Evaluation

2. Positive Communication

3. Cooperation

4. Commitment

5. Planning

6. Monitoring

7. Relationship

8. PerformanceMotor

9. PerformanceCognitive

.22

- . 89

- . 05

.06

.27

- . 03

- . 14

.23

.15

.20

.01

.17

.39

.27

- . 14

.36

..34

.25

.17

.39

.38

__

.21

.20

.36

.36

.32

.27

.09 .06

.05 .28 .65

.22 .26 .46 .46

Note. All correlations of greater absolute magnitude than .23 are significant at the p < .05 level. Given

the multitude of correlations tested (55), there is the possibility of capitalizing on chance. However, only

5%, or approximately 3 of the 55 correlation coefficients, would be significant if chance alone were

operating. Our results indicate 26 significant correlation coefficients, thus suggesting the need for further

examination.

ported: Commitment was positively related to task performance.

Task monitoring (Hypotheses 6b and 6c) was also positively

related to task performance, as was cooperation (Hypotheses

7b and 7c). Planning {Hypotheses 2b or 2c) and positive com-

munication (Hypotheses 4b and 4c) were not significantly re-

lated to task performance.

Group processes mediating relationship and performance.

We used the test for mediation described by Baron and Kenny

(1986) to test the contribution of the mediating processes be-

tween relationship level and task performance. First, the pre-

dicted mediators were regressed on relationship level. On the

basis of the previous analyses, we excluded planning and moni-

toring because they were not found to have significant main

effects of relationship, and we excluded positive communication

because it was not significantly related to performance. Commit-

ment and cooperation were significantly related to relationship

level ( f i - . 389, p< .001, andB = .184,p < .01, respectively).

Second, relationship level was significantly related to the depen-

dent variable, task performance (B = .45, p > .001). Third, the

effect of relationship became nonsignificant when the mediator

variables were included in the regression analyses on group

performance (average B = .09, all ps were ns). Thus, the medi-

ating role of commitment and cooperation on task performance

was supported (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

Task type, group process, and performance. To examine the

Table 4

Summary of Regression Analysis for Variables

Predicting Performance

Variable B SEB

Positive Communication

Planning

Commitment

Monitoring

Cooperation

Note. N = 106. R = .55.

*p < .01.

0.288

0.062

1.340

1.210

0.780

.228

.055

.134

.049

.154

-. 127

-. 190

.432*

.449*

.376*

hypotheses that task type moderates the relation between critical

evaluation (Hypotheses 3b and 3c) and morale-building commu-

nication (Hypotheses 4b and 4c), we conducted regressions

separately for each task. We used the positive communication

variable to test the hypothesis regarding morale-building com-

munication because it included the items designed to measure

morale-building communication. In support of Hypothesis 4b,

positive communication was positively related to performance

in the motor task (B = .22, p < .001), and in marginal support

of Hypothesis 4c, it was negatively related to performance in

the cognitive task (B = - . I 3 , p < .07, respectively). In addition,

critical evaluation was positively related to performance in the

cognitive task but negatively related in the motor task (B = .16,

p < .001, and B = -.21, p < .001, respectively). Although

friendship did not influence critical evaluation in this study (Hy-

pothesis 3a), Hypotheses 3b and 3c were supported: Critical

evaluation was positively related to performance in the cognitive

task and negatively related to performance in the motor task.

We included task order as a variable in our design to control

for task experience across tasks. A 2 (task) X 2 (relationship)

X 2 (order) ANOVA revealed significant main effects for order

on positive communication, F( l , 52) = 5.96, p < .05, and

commitment, F(l, 52) = 6.68,p < .05. Groups who performed

the cognitive task prior to the motor task had more commitment

(M = 4.96) than groups who performed the motor task prior

to the cognitive task (M = 4.66). Groups in which the motor

task preceded the cognitive task engaged in more positive com-

munication (A/ = 1.78) than those in which the cognitive task

preceded the motor task (M = 1.50).

Discussion

This study provides information about group processes that

mediate the effect of relationship level on task performance.

The results indicate that several process differences in friendship

and acquaintance groups account for the performance superior-

ity of friendship groups on both cognitive and motor tasks. Prior

research has suggested that friendship among group members

may harm a group's performance, because the group's focus

may be on social interaction rather than the task (Bramel &

786 JEHN AND SHAH

Friend, 1987; Homans, 1951). The results from this study indi-

cate that although friendship groups do communicate more and

provide more positive encouragement than acquaintance groups,

they also are more committed and more cooperative, which leads

to higher performance levels.

Regardless of the type of task the group performed, commit-

ment, cooperation, and task monitoring increased group perfor-

mance, thus demonstrating why friendship groups performed

better than acquaintance groups. There was no significant differ-

ence between the amount that friends and acquaintances

planned, nor was planning related to performance in either the

model-building task or the decision-making task. One explana-

tion is that tacit coordination occurred without discussion (Wit-

tenbaum, Stasser, & Merry, 1996), which was not captured by

our verbal coding scheme. This is unlikely, because our measure

of planning included self-report and video ratings of nonverbal

behaviors; however, the reliability for this scale was one of the

lowest (.71). In addition, Argote (1982) found that in organiza-

tions, in-process planning improves effectiveness when the task

has a high level of uncertainty. In our study we measured only

in-process planning, therefore missing any preplanning that

might have taken place (Weingart, 1992). In addition, both of

the tasks were very structured, with low levels of uncertainty;

therefore, it may not be surprising that we did not find significant

results for planning and performance.

Similar to Weldon et al. (1991), we found that task monitor-

ing was positively related to task performance. In addition, we

expanded Weldon et al.'s model by demonstrating that friend-

ship, cooperation, and commitment increase task performance.

Similar to Shah and Jehn (1993), we found that processes in

friendship groups are not consistent across tasks. Friendship

groups appear to engage in behavior and interaction patterns

beneficial to the task they are performing. This suggests a feed-

back mechanism that may be more common in friendship groups

than in acquaintance groups (Guzzo & Dickson, 1996). Poor

performance reflects negatively on a group, and it is more diffi-

cult to disassociate oneself from a group of friends than from

a group of acquaintances (Tesser & Smith, 1980).

Processes not related to performance may be less likely to

occur in friendship groups because of associations among mem-

bers and the strong obligation to be committed to high perfor-