Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fire, Blood and Feathers

Uploaded by

romrasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fire, Blood and Feathers

Uploaded by

romrasCopyright:

Available Formats

Fire, Blood and Feathers

An exami nat ion of common cross -cultural, aspects: social organization, defensive postures and

religious perspectives within Nahuatl, and other indigenous cultures.

The study of any ancient indigenous culture is, of itself, a daunting task. When such a task is

compounded by the lack of first hand empirical evidence, the challenges may seem

insurmountable. Luckily there always seem to be a handful of dedicated and enthusiastic

researchers seeking after the missing links. They have dedicated their existence to the expansion

of collective knowledge, by skillfully and meticulously unraveling the secrets of the past,

shedding light upon these deep, dark and hidden mysteries

1

Written Assignment

Fire, Blood and Feathers

An examination of common cross-cultural, aspects: of religious and mythological perspectives

and symbolism within Nahuatl, and other indigenous cultures.

James P. Welch

IDR CAS 5960-067

The University of Oklahoma

Master Degree Program in International Area Studies

Professor: Karl Offen, Ph.D.

August 29, 2012

2

Fire, Blood and Feathers

Introduction

The study of any ancient indigenous culture is, of itself, a daunting task. When such a study is

compounded by the lack of first hand empirical evidence, the challenges may seem

insurmountable. Luckily there always seem to be a handful of dedicated and enthusiastic

researchers eager to seek out the vital missing links. They have dedicated their existence to the

expansion of collective knowledge, by skillfully and meticulously unraveling the secrets of the

past, shedding light upon these deep, dark and hidden mysteries. The focus of this particular

research is primarily upon the Aztecs culture in general and the Mexica in particular. The three

most noteworthy sources providing information about this ancient civilization are: a vast oral

tradition; colonial period (and limited pre-colonial) codices, modern archeological research.

Their fundamental conceptions in the areas of religion, mythology and symbolism are examined

in the light of other highly developed civilizations, notably the Egyptians, the Celts and the

Hindus.

When comparing the cultures of Mesoamerica with those of other advanced ancient

civilizations, the existence of an oral tradition for the transmission, the challenges of tracing such

history becomes readily apparent. This sense of passing history, more or less exclusively,

through an oral tradition is a common ancient practice and evidenced in several other cultures

notably: The Greeks, the Celts, the North American Indian, the Inuit, as well as certain Hindu,

Islamic and African cultures. Interestingly, a modern occurrence of oral transmission is related to

political oppression of expression, evidenced in former communist countries. The downside of

oral transmission can be associated with: faults of transmission, and errors of transcription and

3

Figure 1

memory. These phenomena can easily lead to manipulation, confusion, exaggeration and false

speculation. In the case of the Aztecs, the Spanish retransmission was often distorted from the

eyes of the conqueror, to depict themselves in a favorable light. Other manipulation was meant

to glorify the heroic Spanish image while demonizing the Aztecs and depicting them as a

ruthless, yet inefficient barbaric people. In this way the Spanish could justify their excesses in

the conquest of the new world. Finally, analyzing specific aspects of any single, given

civilization is an arduous enough task. The complexity of Aztec society magnifies this problem

proportionally. Such difficulty is compounded, further, when attempting to draw parallels across

diverse cultural frameworks. Serious, dedicated scholarship, archeological and geological

evidence, however, can help to broach some of these shortcomings.

When considering the development of any culture, passing from the phase of hunter gatherer

to that of a more sedentary agricultural society, there are, obviously, similar patterns to such

development, which are well worth bearing in mind (see Fig 1 below).

4

The Nahuatl Culture Historical Overview

There are many unknowns concerning the true origins of the actual migrations from the north

which led the future Aztec people to the valley of Mexico. More recently there has been

increased research and several archeological findings, have helped improve knowledge and cast

light upon many of these mysteries. Even the name Aztec remains, somewhat, a mystery as

Peterson indicates,

These barbarians, who later became highly sophisticated, are called by many names

Aztec, Mexica, Culhua-Mexica, Tenocha, and Teo-Chichimeca. The name Aztec is

now popularly misapplied to almost all Mexican Indians, because of the persistent

glorification of it by writers since William Hickling Prescott. The people living where

Mexico City is now called themselves Mexica, and their capital city Tenochtitlan or

Mexico. The name Mexico probably means in the navel of the Moon. The name

Aztec will be used here for the people of Tenochtitlan [as it I has been for this research

paper].

Despite the confusion and inconsistencies several important facts remain, nonetheless,

indisputable. The Aztecs, (an ethnologically diverse group of Nahuatl speakers) and more

particularly the descendants of the 7

th

and last tribe of the Chichimec (the Mexica), adopted the

gods and traditions of the previous Toltecs whom they admired. They were, also, as previously

noted, Nahua speakers, a language pertaining to the Uto-Aztecan dialect. As Peterson points out

in his estimation, North-western Mexico seems to be a probable place of origin for the Aztecs,

who spoke Nahua, one of the large Uto-Aztecan family of languages that extends north into the

United States.

1

This would seem to make sense since the ancient capital of Tula, the center of

Toltec culture, is located directly northwest of Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs had also traced their

ancestry back to that city. Interestingly Michael Smith seems to confirm this assumption when he

1

Peterson, Frederick. Ancient Mexico. 10th. New York: Capricorn Books, 1962. 86

5

writes, The Toltec peoples, whose capital was Tula, maintained trading relationships with

distant areas of Mesoamerica, although they did not dominate central Mexico as their

Teotihuacan ancestors had. The collapse of Tula coincided with the arrival of the Nahuatl-

speaking Aztec immigrants in central Mexico during the twelfth century.

2

Most importantly

Smith states that, The Aztecs adopted many characteristics from these earlier civilizations,

including gods, rituals, economic institutions and principles of kingship and city planning.

3

According to their own pictographic descriptions the Aztecs claimed to have originated from

a currently unknown place known as Aztlan. Smith lists this first wave of immigration as the

onset of the Early Aztec period, 1150 1530 CE. The Aztecs were sub-divided into several

different ethnic groups, living in distinctive regions and all practicing Nahuatl language and

social customs. This may well have be the initial framework for the establishment of the calpolli,

the single most important framework within their complex social structure. The Aztec system

was, in fact, so efficient and highly evolved that the Spanish left it, more or less, intact instead of

imposing their foreign and unknown system instead. Regardless, the Aztecs were a migrant

warrior people who eventually settled in the valley of the region known today as Mexico City,

and established their capital Tenochtitlan.

The Aztecs rapidly grew in both strength and numbers. They were fierce warriors and ardent

conquerors and practiced a system of indirect empire. This refers to a practice of conquering

vassal states and receiving tribute, but not exercising direct sovereignty. During the late Aztec

period (1350-1520 CE) the population exploded from approximately 500,000 to 3,000,000

million persons (Smith 2006, 2).

2

Smith, Michael E. Aztec Culture an Overview. Essay, Tempe: Arizona State University, 2006, 2

3

Ibid., 2

6

Much of their imperial conquest was seen with a jaded eye from their subjects and this was a

boon to the Spanish who found ready allies during the period of the conquest.

Magic, Myth and Religion: Consistent themes

The Aztec mythological and religious system of belief was highly developed and extremely

complex. Part of this complexity lies in their past habit of adopting and incorporating gods, rites

and rituals of conquered vassal states, while, at the same time, maintaining their own. A feature,

relative to most primitive and ancient cultures, is an attempt to understand and explain their

existence, in relation to their surrounding environment and the forces of nature. Religion

permeated every aspect of the Aztec daily life. It shaped and controlled society, warfare, politics

and agriculture. This is usually done through the creation of a cosmological myth; often one of

the first stages of social development. The creation stories surrounding the founding of the

Aztecs were surprisingly flexible and quite adaptable to their nomadic life style. Peterson writing

on the creation myths and Teotihuacan states, Teotihuacan is Aztec for The place of the gods;

but the place was in ruins long before the Aztecs came. According to ancient legends the gods

lived at Teotihuacan, and the Sun and the Moon were created there.

4

The Moon and Sun figure frequently in the theme of creation myths. The creation of the

pyramids of the Sun and the Moon, in Teotihuacan, coincide in Aztec mythology with the

creation of the 5th Sun, the Earthquake Sun, and ends in a struggle between 2 gods; Tecuciztecatl

and his humble rival Nanahuatzin. Basically, the cowardly Tecuciztecatl receives a rabbit in the

face and becomes the Moon, while the humble and courageous Nanahuatzin, remains in place as

the Sun. This was the beginning of humanity, and is widely spread throughout Mesoamerican

4

Peterson, Frederick. Ancient Mexico. 10th. New York: Capricorn Books, 1962, 60.

7

Figure 2

Ometecuhtli/Omecihuatl

culture. The actual Aztec story itself, however, relates only to the Aztecs and their leader

Huitzilopochtli. This particular tale relates, in part, to the primordial dismemberment cycle of

creation myths. According to the Aztec myth Huitzilopochtli, is born of

Coatlique (see Fig 1). Coatlique is seen as having become unjustifiably

pregnant (adultery was punishable by death with the Aztecs). Her

daughter, Coyolxauhqui, and her 400 brothers (Centzon-huitznahuas)

climbed the serpent mountain (Coatepec) and slayed their mother.

Huitzilopochtli was born completely attired and slew both his sister (who

became a lunar goddess) and each of his 400 brothers in turn.

Some interesting allegories present themselves here. There is, of course the concept of

Immaculate Conception (rightly or wrongly). It appears Coatlique became pregnant after stuffing

a ball of feathers in her breast (some accounts record her belt. Feathers perhaps link the

hummingbird association with Huitzilopochtli??). Further, the idea of the son revenging the

parent is a very widespread theme throughout ancient mythology. For instance, one might

consider the Egyptian myth of Horus avenging his father Osiris by slaying Seth. An essential

theme that underlies these mythic tales is the ultimate importance of the

correlation between the moon and the sun. An eclipse seemed to herald the

possible end of sunshine, and hence life. This aspect shall be discussed in

greater detail in the following section.

Perception of Duality: Different yet the same.

This important concept requires a separate explanation, and could easily serve as the subject of a

title all on its own. In the cosmological cycle, where the world is often created out of chaos, there

Figure 1 Coatlique

8

is often either a single god, with a dual male/female personae, or alternatively seen as a separate

male and female entity. While they are often seen as opposites, they are also part and parcel of

the same integral unit. The very first fertility gods/goddesses can be recognized in the votive

figures as funerary offerings in early burials. Peterson notes, The first fetish figurines, of baked

clay, are female and probably represent fertility goddesses as symbolic of the generative

principles of reproduction, birth and growth.

5

This precept is based upon the simple elementary

composition of the world around us. This can be elemental, physical or spiritual. For instance,

the most visible evidence of direct contrasts can be seen in; sun/moon; water/fire; day/night;

earth/sky; life/death; dark/light; chaos/harmony; old/young; weak/strong; mountain/valley, etc.

Professor Peterson reaffirms this point when he writes,

Another characteristic of most Mexican religions was dualism. All things were

based on male and female elements that gave birth to the gods, to the world, and to

man. Celestial and natural phenomena were attributed to eternal struggles between

hostile deities. This accounted for night and day, light and dark, life and death

growth and decay good and evil, sickness and health. The Mexican ball game may

be symbolic the eternal struggle between light and dark as represented by

Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca.

6

These are also reflected within the belief of social hierarchy

thus, where there are poor and uneducated masses, there

are also a few well educated nobles (c.f. the inverse).

Duality can, therefore, also be seen in its ultimate

manifestation in the various gods of ancient civilizations.

Shiva of the Hindu pantheon is known as having both a masculine and feminine

aspect (refer to fig 3). As can be seen, not only are the male and female aspects

5

Peterson, Frederick. Ancient Mexico. 10th. New York: Capricorn Books, 1962, 123.

6

Ibid, 126.

Figure 3 Shiva Elephanta Island

9

represented, but if the viewer regards from a right or left angle at one half of the

face, there is a distinctly masculine or feminine characteristic as well. Another

symbol of the inherent importance of the concept of duality among the ancients can

be seen in the bi-compositional nature of the Hindu goddess Mahadevi. There are

also many manifestations of this duality of purpose in Ancient Egypt where, the

kingdoms were divided into upper and lower halves and the desert on either side of

the Nile, into red and black sides. Sekhmet incorporates the seemingly opposite

virtues of the lady of terror and the lady of life, simultaneously. J. Hill notes

that, Sekhmet (Fig 4), was mentioned a number of times in the spells of The Book

of the Dead, as both a creative and destructive force. Above

all else, she is the protector of Ma'at (balance or justice)

named "The One Who Loves Ma'at and Who Detests Evil".

7

Note the concept of balance between two opposing forces. The

fact that there is no judgment made between right or wrong,

merely the weighing of inverse characteristics. Ironically Celtic mythology and

religious belief, is based upon the concept of three or the triad. Still, as previously

explained, this could also be a question of the duality being combined in a separate

and hence third aspect as well. Duality was not merely encompassed within the

anthropomorphic manifestations of the various deities, but a part of everyday life

and a constant reminder of the precariousness on mans life on earth. Finally, there

are numerous instances where the concept of duality plays a major role in the

7

Hill, J. Ancientegyptonline. 2010. http://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/Sekhmet.html.

Figure 4 Sekhmet

10

cosmology and mythical beliefs of the North American Indian.; for instance, the

story of The Good twin and the Evil Twin among the Yuma.

Dismemberment

Aztec mythology is varied; it changes over time and has many political nuances. There are,

however, similarities with various other belief systems. There is the Egyptian, Osiris/Isis saga, or

that of the Hindu version of the Sati/Vishnu saga, for instance. These are often dismemberment

tales where the parts of the dismembered god are scattered to become either people or places.

Strong correlations exist notably in the following myths:

Osiris is slain and his body parts are recuperated by Isis. He is then revenged by his son

Horus, who was incidentally also dismembered according to Egyptian mythology. Thus,

Budge, renowned Egyptologist, writes, Now as the deceased is identified with Osiris, it

is clear from the above passages that the head of Osiris was cut off, that his body was

broken up and its internal organs separated, and that his bones were scattered.

8

Huitzilopochtli, springs from his dead mother, in full battle array, and slays his 400

brothers and his evil sister (see text).

Devi is a Hindu goddess which encompasses the concept of duality (see below). That is,

the goddess contains two opposing personifications simultaneously. She can be, Kali, a

goddess of carnage and destruction or a supreme protector in her form of Parvati. Related

to the dismemberment cycle, Vishnu was forced to cut Shivas wife,

Sati (another manifestation of Mahadevi), into 50 pieces.

The Sun: the moon and the stars.

It would be remiss not to emphasize the importance of the solar deity within

nearly every single known ancient civilization. Often the Sun plays the

primordial role in any religious pantheon. Surya was the Hindu sun god,

8

Budge, E.A. Wallis. Osiris & the Egyptian Resurrection. Vol. 1. New York: Dover Publications, 1973, 70.

Figure 5 Mahadevi as

Paravati

11

Amaterasu in Japan, Lugh of the Celts, Re, of course that of the Egyptians, and Tezcatlipoca that

of the Aztecs. These deities were, further, often associated with the harvest and agricultural

production and, not unsurprisingly, human sacrifice. In pure and simple logic, the Sun nourishes

the people and therefore the people are responsible to nourish the sun as well. In the

cosmological cycle of the Aztecs, the earth had been created five times with five different suns.

The fifth renewal, prophesized during the calendar year 1 Ce Acatl (one reed), foretold the return

of Quetzalcoatl. Unfortunately for the Aztecs, this coincided with the arrival of Hernando Cortes

and his band of Spanish Marauders, in 1519. The eclipse, which took place in 1519, was seen as

an ominous portent to the Aztecs. The struggle between Quetzalcoatl and that of Tezcatlipoca

was representative of this struggle between the Sun and the Moon, between light and dark.

Serpents Crocodiles and Other Beasts

The serpent has long been a dual symbol of fertility,

treachery and death. Nearly all ancient civilizations have

the image of the serpent, or its stylized form-the dragon,

in their belief systems. The serpent is often symbolically

represented as the struggle between the day and night and

life and death. Of course a long standing reminder of the role of the serpent in fertility can be

seen in the Judeo-Christian story of Adam and Eve. Crocodiles figure prominently in both Aztec

and Egyptian myths and legends. If there are so serpents or crocodiles, then dragons can also

fulfill the function, such as in the case of China and Japan. There are specific qualities which are

related to the serpent/crocodile images, or deities, such as: power, fertility, cunning, treachery,

childbirth, and general fertility. Huitzilopochtli, himself, is born holding a serpent in one hand,

while many of the Hindu and Egyptian gods are literally ensconced by cobras. The ancient

Figure 6 Celtic God Cernunnos with serpent

12

Egyptians made extensive use of both beasts, in animistic and zoomorphic idealizations. Thus,

Sobek, the crocodile god, associated with the all-important Nile the heartbeat of ancient

Egyptian existence, saw himself enshrined for all eternity through the mummification of his

living representation. The Cobra was the divine protector of the Pharaoh, and can be seen on the

crown represented by Wadjet, the cobra goddess of Buto, with her fire spitting tongue. Wadjet is

accompanied by the protective wings of Nekhebet, the vulture goddess, recalling the principle of

dualism mentioned previously. Thus, duality combined in a single, sacred entity becomes, once

again, abundantly clear since Nekhebet of Upper Egypt and Wadjet of Lower Egypt, are

combined symbolically upon the Uraeus crown of the Pharaoh, divine ruler of both lands. If

further proof were needed to emphasize the importance of the concept of duality in ancient belief

systems, this is provided by J.E. Manchip White when he writes, The crook and flail

symbolized simultaneously the wooing and coercive nature of the Pharaohs power.

9

Colors, Directions, Celestial Symbolism and the Magic Number 4

The significance of the concept of duality, to the Aztecs, was important yet it pales in

comparison with the importance of the number 4. The number four and the concept of four items

or segments are a reflection of the importance that the Aztecs attached to the four directions.

According to the New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, The north was the dwelling place

of Tezcatlipoca, the south that of Huitzilopochtli, the east that of Tonatiuh, and the west that of

Quetzalcoatl.

10

According to the readings it became readily apparent, to this author, that there

was actually a fifth direction, never really mentioned yet always present. It is either physically

9

White, J.E. Manchip. Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1970, 13

10

"Mythology of the Two Americas." In New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, edited by Felix Guirand,

translated by Richard Aldington, & Delano Ames, i - 500. Twickenham: Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1987,436.

13

or spiritually the direction or state of center. The center represents the heart of any being,

object entity or structure. Thus, while Tenochtitlan was divided into four major Calpolli or

sectors, there was also a very important central section. The importance of the number four and

its relationship to harmony, organization, directions and colors were not lost on other

civilizations either. The Japanese and subsequently the Chinese also attached great importance

to the directions and their anthropomorphic representation (See Table 1 in Appendix B). The

number four is symbolic of perfect harmony as evidenced in the earliest Egypt ian hieroglyph

that, of Pi, represented by a simple square and standing for house or dwelling. Hence that

most basic tenet of society, shelter, is also based upon the harmonious concept of four.

Another important symbol representing the cosmic connections between man and spirit is

represented by the wheel or cross. This symbol is often combined to represent a cross within a

circle, thus evoking the idea, once again of the four cardinal points of the universe. Yet, the

wheel itself is, a symbol of movement and regeneration.

The number 4 (as well as the numbers 13 and 20) had great mystical significance within the

Aztec belief system. Four is seen in the construction of their palaces and pyramids. Note that, as

previously hypothesized, the fifth unspoken direction can be seen in the pyramids. The fact that

they rose several hundred feet from the center, was representative of the desire to physically

approach the realm of the gods. Furthermore, it might be logical to postulate that the four priests

holding the limbs of the sacrificial victims would be representative of the cardinal points and that

the sacrificial priest performing the duty, would represent the center and thus the communion of

the beating heart and the living god.

14

Other significant manifestations of the number four, persist in several different cultural myths

including, unsurprisingly those of the North American Indians. Consider this telling excerpt from

the Jicarilla [Apache] genesis myth: They played a fourth time [the thimble and button game],

and again the people won. The sun came up in the east, and it was day and the owl [traditionally

a dark omen] flew away and hid.

Sacrifice: When is a sacrifice not really a sacrifice?

In todays society most individuals would normally consider the sacrifice of humans as abhorrent

and repugnant as a practice. However, it is not possible for a social scientist to be jaded by such

social constraints when researching cultures of the past. Additionally, the sacrifices of the past,

often, made no distinction between young and old, male or female, thus, there is even evidence

of child sacrifice. Sacrifice was seen consciously, as a necessary tribute to placate the gods and

avoid incurring their wrath. Unconsciously, sacrifice represented the cycle of life, death and

renewal. This was a sort of ancient utilitarian view of the world.

Sacrificing a few would save the lives and prosperity of the many.

Peterson writes, The divine mission of the Aztecs was to feed the

gods, and the most precious food available was human blood.

11

These

sacrifices were carried out atop the large temple dedicated to

Huitzilopochtli, where the victim would have his beating heart ripped

from his chest, while laying splayed across the techatl-stone while held

by four priests.

11

Peterson, Frederick. Ancient Mexico. 10th. New York: Capricorn Books, 1962, 152-153.

Figure 7 Aztec Sacrifice and

the number 4.

15

Human sacrifice, like other aspects of mythological worship and religious rites, were also

wide spread in the ancient world. Julius Caesar, in his conquest of Gaul, writes of Celtic

sacrifices where slaves are burnt alive along with their deceased master, as well as the practice of

the infamous wicker man. Of course, most readers will be well familiar with ritual retainer

sacrifice as practiced in early dynastic Egypt. This practice, however, was not as wide spread, as

might be imagined and disappeared, according to most accounts, probably by around the end of

the first Dynasty in 2890 BCE.

12

The jury is still out on the question of both human sacrifice and

that of the closely related phenomenon of cannibalism, and a definitive verdict does not look

probable in any immediate future. Scholars argue on both sides of the aisle. Anwaar Abdalla,

writing for the Washington Times cites Reisner, Scholars continue to debate whether the

sacrifices took place. George Reisener, the famous Egyptologist, says the early tombs of Abydos

and Sakkara like the tombs of King Aha (c.3100 B.C.) and King Djer record human sacrifice.

Reisener says the different architecture of the tombs suggested that the servants were buried alive

with their tools and vessels. Reisener also believed that King Djers queen was buried alive along

side[sic] her husband. He believes that in Abydos, there are at least 162 sacrificial tombs.

13

Aztec sacrifice, as mentioned previously, cannot be judged by present day values.

Unfortunately, perhaps the most well-known aspect concerning this important ancient

civilization, resides in the collective memory of their human sacrifice rituals. Human sacrifice,

however, most certainly existed prior to the arrival of the Aztecs as evidenced by archeological

research and findings. The Aztecs merely brought the practice to unprecedented new heights.

The sacrificial ritual, however, was not a mere reflection of savage blood thirstiness, but rather

12

Gavin, John. "Abydos: Egyptian Afterlife." National Geographic, 2005.

13

Abdalla, Anwaar. "Human sacrifice in Ancient Egypt." Washington Times, February 2012.

16

was based upon rather practical considerations of the epoch. The three principal functions

served by ritual human sacrifice by the Aztecs were:

Obtain food for the gods in order to appease and placate them and receive their

blessing and protection in return.

The large volume of sacrificial victims served to remind wayward or reluctant vassal

states of the consequences of rebellion or for failure to respect the obligations of tribute

and obedience.

The sacrifices served as an opportunity for the warrior class to boast and display its

prowess in the often arranged gladiatorial type events which were held.

Each of the gods required a different sort of sacrifice for appeasement, which was related to his

or her cosmic nature. Thus, David Leeming writes, Tlalocs sunlit, song-filled court, was to

acquire a sinister aspect, and his obsequies were to become the most horrific of all, as suckling

infants and small children were sacrificed to a ravening rain-godon the theory that their tears

would encourage spring showers.

14

This took place as a regular occurrence on the first months

of the Aztec Calendar to assure plentiful rain and bountiful harvest. Xipe Totecs victims would

be tied to a stake, their heart region painted white and then shot full of arrows. The belief was

that their flowing blood would nourish the earth. The victim was then flayed and a priest would

wear the victims skin. This is of course a ritual representation of the earth shedding its skin,

and the renewal of the seasons. The flaying portion of the ceremony was dedicated to the Earth

mother goddess Teteoinnan. The Aztecs were not the only culture to sacrifice victims to various

gods. As mentioned earlier, Julius Caesar made note of Celtic sacrifice. Other forms of Celtic

sacrifice, for example, were the hanging of Victims for Esus and the burning alive of victims for

Taranis. The ritual of Esus mirrors that of the Aztecs Xipe Totec. Victims would be hung from

14

Leeming, David. Mythology. New York: Newsweek Books, 1970, 132.

17

trees and ritually wounded; the patterns of their blood loss would serve as an oracle.

15

The

unfortunate victims dedicated to Taranis, the god of the sky, were immolated. The sacrificial

victims of Teutates, a tribal protective god, were drowned, by being immersed head first into a

vat. Finally, other examples of early Celtic sacrifice are evidenced with the remains of the

Lindow man. The 1

st

Century Roman poet Lucan mentions all three of these deities, Esus,

Teutates [also written Toutatis] and Taranis.

There was an aggressive campaign by the Catholic Church to stomp out what they saw as

barbarous pagan rituals. Despite these efforts, there is some evidence according to Lockhart and

others that preconquest rituals and practices endured, particularly in rural areas, even after the

advent of Christianity. Thus Lockhart writes, Where ever Christianity left a niche unfilled, it

appears, there preconquest beliefs and practices tended to persist in their original form. The

remarkable thing is how unchanged and untouched these practices remained.

16

Cannibalism

Related to the practice of human sacrifice, was a ritual practice of cannibalism.

Up until recently, many scholars have assumed that this practice was wide

spread and based upon population pressure and famine. One proponent of such

a hypothesis is Michael Harner. Harner, however bases much of his theoretical

perspective upon the writings of Cortez and other chroniclers of the period, as

well as upon speculative hypothesis. The author does make some interesting

observations, based upon recorded data. Harner indicates, for instance the

15

MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

16

Lockhart, James. The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992, 258.

Figure 8 Florentine Codex

image Franciscan friar

Bernardino de Sahagn

18

need for protein and the lack of domesticated mammals as a food source. In this same vein he

writes, Unfortunately, their ingenuity [land reclamation via the chiampa system] could not

correct their lack of a suitable domesticable herbivore that could provide animal protein and

fats.

17

The fundamental hypothesis as laid out by Harner is that, the Aztec sacrifices, and the

cultural patterns surrounding them, were a natural result of distinctive ecological

circumstance.

18

The premise, can of course be made, that if the large number of sacrifices

performed by the Aztecs were seen as normal and acceptable behavior, then why not

cannibalism as well? According to Harner, the evidence has been overlooked or largely ignored

by researchers, due to various factors such as personal conscious or unconscious distaste,

concerning the subject itself and Mexican researchers, for preservation of the national image.

Harner does make a provocative inquiry when asking the obvious question; what did the Aztecs

do with the enormous amount of bodies resulting from their sacrificial rituals? Actual empirical

evidence, such as that presented by Archeological digs (such as the Tlatelolco section of Mexico

City during the period of 1960 and 1969), is rather scarce. Here Harner runs into difficulty and

is obliged to support his hypothesis through the use of 16th century literature of questionable

reliability. His final argument in support of his hypothesis is based upon the human need for the

8 essential amino acids. Some researchers have argued that these amino acids could be obtained

through a steady diet of maize and beans [two of the staple crops]. Harner argues however that,

the Aztec commoners would have to consume large quantities of maize and beans

simultaneously or nearly simultaneously year-round.

19

He underscores the possibility of such a

solution by pointing out the frequent periods of famine and extensive crop failures. Harner sums

17

Harner, Michael. "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice." Natural History 86, no. 4 (April 1977): 47.

18

Ibid, 47.

19

Harner, Michael. "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice." Natural History 86, no. 4 (April 1977): 49.

19

up his position by proposing, A materialist ecological approach reveals the Aztecs to be neither

irrational nor mentally ill, but merely human beings who, faced with unusual survival problems,

responded with unusual behavior.

20

Montellano, in direct opposition to Harner, questions these assumptions and presents a well-

documented and scientifically sound counter argument. His research compares protein intake of

the Aztec agricultural cycle to that of the possible protein contribution of cannibalism.

According to Montellano, the ritual cannibalism, of the Aztecs, was practiced only by a small

minority of nobles [25%] and that only the limbs were consumed. This would seem to argue

against the perception of the cannibalism as a source of population sustenance. Further,

Montellano argues that the cannibalism was not motivated by starvation but by a belief that this

was a way to commune with the gods.

21

Summary

The field of study dedicated to any single civilization has both advantages and disadvantages.

Researchers devote great time and effort, often entire lifetimes,

to the elucidation of various mysteries enshrouded within those

civilizations. Such specialized knowledge helps to provide

invaluable insight into the past and to clarify areas of

uncertainty. One of the seemingly counterintuitive ironies, is the

fact that by becoming so specialized, they can often become blinded to the larger intra-cultural

anthropologically based belief systems, which influence the general beliefs and behavior of man

20

Ibid, 51.

21

Montellano, Bernard R. Ortiz de. "Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological Necessity?" Science 200, no. 4342 (May

1978): 611-617.

Figure 9: 4 day signs: Flint knife; Flower;

Rain; Crocodile

20

as a species. One must bear in mind the possibility of distortion, while maintaining an immense

respect for the knowledge and dedication of those involved in translating, understanding and

transcribing these ancient tales into modern terms. For instance, Peterson speaking of the Aztecs

system of courts and justice in totally modern terms, at times, distorts understanding of that

ancient reality. There is also a possibility of becoming too close to a subject and not entirely

objective. Thus, it is important to take a step back. When an enigma is presented, there may be a

possibility to draw parallels through the cross-cultural examination of another indigenous people

and their belief system. It might be a good idea to consider this aspect when forming future

teams of archeologists. It would be a worthwhile endeavor to have cultural anthropologists and

ethnologists participate in research, in order to bring in added dimensions and unforeseen

perspectives to such a study.

Another significant problem as mentioned in the introduction, has been the tendency, in the

past, of researchers to rely too heavily and be influenced by second hand accounts, such as those

provided by the Spanish, in the case of the Aztecs. Research of ancient cultures is fraught with

obstacles, such as conflicting accounts, missing clues and destroyed evidence. There are,

additionally, as often noted in various texts, severe problems of funding and a lack of resources

in order to carry out the necessary research. In todays fast paced, high-tech world, it might

appear, to some, that the immediate past, history, has little or no bearing on the present, or that

the distant past, archeology, ethnology, anthropology, etc., has even less relevance. In such light

it is useless to even speak of the importance of the prehistoric sciences such as, paleontology or

geology. But this would be a short sighted view of humanity; as if to say the tree has nothing to

do with the seed. Ultimately the achievements of modern society are the result of a long

process of development, and can only be measured by the past. To understand any society today,

21

it is imperative to understand how that society developed, what its roots are and from whence it

came.

Researchers such as Lockhart, Peterson and Soustelle, to mention but a few, perpetuate the

great traditions of their predecessors such as Champollion. In a spirit of healthy curiosity and

academic inquiry, they dedicate their time and knowledge, to the meaning and understanding of

who we are and where we came from. They are often hardly recognized or rarely supported

for their contributions. However, their ultimate mission supersedes such base concerns. In many

ways, they too, like the Aztecs and the other ancients, find a divine mission in seeking out the

past and shedding light upon these ancient mysteries.

22

References

Abdalla, Anwaar. "Human sacrifice in Ancient Egypt." Washington Times, February 2012.

Advameg Inc. "Aztec Mythology - Myth Encyclopedia - god, story, legend, names, ancient,

animal, snake, war, world, creation." Encyclopedia of Myths.

http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/Ar-Be/Aztec-Mythology.html#b (accessed August

18, 2012).

Budge, E.A. Wallis. Osiris & the Egyptian Resurrection. Vol. 1. New York: Dover Publications,

1973.

. The Dwellers on the Nile. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

Daniel, Douglas A. 1992. "TACTICAL FACTORS IN THE SPANISH CONQUEST OF THE

AZTECS." Anthropological Quarterly 65, no. 4: 187. MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost

(accessed August 20, 2012).

Doyle, Diana. "Azec and Mayan Mythology." Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute, 2012.

Emery, W.B. Archaic Egypt. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1987.

Erdoes, Richard, and Alfonso Ortiz, . American Indian Myths and Legends. New York: Pantheon

Books, 1984.

Gavin, John. "Abydos: Egyptian Afterlife." National Geographic, 2005.

Goodrich, Norma Lora. Ancient Myths. New York: Mentor, 1960.

Graulich, Michel. 1997. Myths of Ancient Mexico. n.p.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed August 20, 2012).

Harner, Michael. "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice." Natural History 86, no. 4 (April 1977): 46-

51.

Hart, George. A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. London: Rutledge and Kegan

Paul, 1986.

Hill, J. Ancientegyptonline. 2010. http://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/Sekhmet.html (accessed

August 15, 2012).

Idell, Albert, ed. The Bernal Daz Chronicles. Translated by Albert Idell. Garden City:

Doubleday Dolphin, 1956.

Ions, Veronica. Indian Mythology. 3rd. London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd., 1973.

James, TGH. An Introduction to Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Publications Ltd.,

1989.

23

Klein, Cecelia F. "A New Interpretation of the Azte Statue Called Coatlicue, "Snakes-Her-

Skirt"." Ethnohistory, 2008: 229-250.

Leeming, David. Mythology. New York: Newsweek Books, 1970.

Lon-Portilla, Miguel, ed. The Broken Spears. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

Lockhart, James. "Postconquest Nahua Society and Concepts Viewed through Nahuatl

Writings." Estudios de cultura nhuatl 20 (1980): 91-116.

. The Nahuas After the Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992.

. We the People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Eugene: Wipf & Stock,

2004.

MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Mencos, Elisa. "Las Representaciones De Xipe Totec en La Frontera Sur Mesoamericana." En

XXIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueolgicas en Guatemala, 2009 . San Carlos:

Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, 2010. 1259-1266.

Milbrath, Susan. 1997. "Decapitated Lunar Goddesses in Aztec Art, Myth, and Ritual." Ancient

Mesoamerica 8, no. 2: 185. Publisher Provided Full Text Searching File, EBSCOhost

(accessed August 20, 2012).

Montet, Pierrre. L'Egypte Eternelle. Paris: Marabout Universite, 1964.

"Mythology of the Two Americas." In New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, edited by

Felix Guirand, translated by Richard Aldington, & Delano Ames, i - 500. Twickenham:

Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1987.

n.d. "Stone disk of Coyolxauhqui, showing the Moon Goddess slain by her brother

Huitzilopochtli; from the site of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico

City), 15th century; Aztec." OAIster, EBSCOhost (accessed August 20, 2012).

Neeson, Eoin. Irish Myths and Legends. Dublin: Mercier Press, 1978.

Oropeza, Martha Ramirez. "Huehuepohualli: Counting the Ancestors Heartbeat." In Community

Culture and Globalization, 30-49. New York: The Rockefeller Foundation, 2002.

Peterson, Frederick. Ancient Mexico. 10th. New York: Capricorn Books, 1962.

Pohl, John M. D. 2002. "AZTECS; A NEW PERSPECTIVE." History Today 52, no. 12: 10.

Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed August 20, 2012).

Read, Kay Almere. 1998. Time and Sacrifice in the Aztec Cosmos. n.p.: Indiana University

Press, 1998. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed August 20, 2012).

Sigal, Pete. "Sexulaity in Maya and Nahuatl Sources." Duke University Press, 2007.

24

Smith, Michael E. Aztec Culture an Overview. Essay, Tempe: Arizona State University, 2006, 1-

7.

Smith, Michael E. "Aztecs." In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion,

edited by Timothy Insoll, 556-570. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Smith, Michael E. "Life in the Provinces of the Aztec Empire." Scientific American, 2005: 90-

97.

Smith, Michael E. "The Earliest Cities." In Urban Life, by George Gmelch, & Walter P. Zenner,

3-19. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press Inc, 2002.

Spence, Lewis. Ancient Egyptian Myths and Legends. New York: Dover Publications, 1990.

Spencer, A.J. Death in Anceint Egypt. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1982.

Tharpar, Romila. A history of India. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd., 1986.

Tymoczko, Maria. 1985. "Unity and Duality: A Theoretical Perspective on the Ambivalence of

Celtic Goddesses." Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 5, 22-37. JSTOR

Ireland, EBSCOhost (accessed August 23, 2012).

White, J.E. Manchip. Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History. New York: Dover Publications

Inc., 1970.

25

Photos and images:

All images are either from the Authors own collection or printed under USC 17 fair usage

clause for educational purposes.

Cover image 1: http://www.ancientscripts.com/images/aztec_conquest.gif

Cover image 2: Artist rendition of Sun God Tonatuih http://aztec-history.com/images/aztec-

sun-god.jpg

Figure 1 : Coatlique http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/aztecs2.gif

Figure 2: Creator gods Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl :

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/borbonicus-20-divination.jpg

Figure 3: Shiva from Elephanta Island Authors collection.

Figure 4: Sekhemet http://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/images/Sekhmet-KomOmbo.jpg

Figure 5 : MahaDevi:

http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/images/mlw_0001_0002_0_img0060.jpg

Figure 6: Cernunnos with serpent: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-

3IU0A16VhJ4/TWHAgmac4xI/AAAAAAAACk4/2Suo7kDF8Ug/s400/Detail%2Bof%2BGund

estrup%2BCauldron%2Bshowing%2BCernunnos.jpg

Figure 7: Sacrifice from the Mendoza Codex

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/sacrifice-i-f-6r.jpg

Figure 8: Cannibalism from the Florentine Codex:

http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/aztecs/sacrifice.gif

Figure 9: Reverse of folio 11 of the Codex Magliabechiano, showing the day signs Flint (knife),

Rain, Flower, and Crocodile.From source:

http://img2.tfd.com/wiki/7/79/Codex_Magliabechiano_11R.jpg

26

APPENDIX A

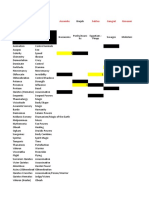

Cross-Cultural Comparison of Deities

Aztec

Egyptian

Hindu

Celtic

Function

Tonacatecuhtli

Tonacacihuatl*/

Ipalnemohuani

Amun

Ammavaru/Br

ahman

Dis Pater/Anu

Dia Cead-Lon

Supreme or 1st

God(s)

Tlaloc

Heryshaf/Min

Amun/Bastet

Bhmi/Parvati/

Manasa/Banka

-Mundi

Rosmerta/Bres/B

rigit/

Nemausicae/

Nerthus/Eostre

Fertility

Huitzilopochtli

(Hummingbird of the

South)

Mixcoatl

Anhur/Neith/An

ouke

Menhit/Menthu/

Mentu

Indra

Lugh/ Cadros

Alator

Belatu/Morrgan(

f)

Caswallan/Neit

War

Tonatiuh,

Re/Harmakhis

Surya (Vishnu)

Garuda

Dia Sul/

Bheil/Lugh

Sun

Ehecatl-

Quetzalcoatl

Amun/Shu Vayu (Pavana) Vintius Wind

Tlaloc (growth

maker)

Indra Rain

Mictlantecuhtli Apophis/Osiris Yama/Mara Cernunnos/Balor/

Chicol

Death/Under or

Otherworld

Ometecuhtli

Omecihuatl*

Brahman/Shiv

a

Morrgan

Duality

Mixcoatl/Opochtli Neith/Pakhet Nodens Hunting

Xipe Totec

Itzpapalotl

Osiris

Banka-

Mundi/Rudra

Cernunnos

Agriculture

Coatlicue (lady of

the Serpent skirt)

Toci/Tlaltecuhtli

Geb/Sopdet

Bhmi

Danu/Corchen/O

anuava

Earth

Quetzalcoatl

Thoth

Ganesha/Saras

wati

Danu

Education/Learnin

g/Priests

* Alternate Appellations.

27

Cross-Cultural Comparison of Deities

Aztec

Egyptian

Hindu

Celtic

Function

Tezcatlipoca (lord

of the smoking

mirror)

Kuk/Nut/Nepht

hys

Ratri

Epos Olloatir/

Night

Tezcatlipoca (lord

of the smoking

mirror)

Nut

Varuna

Taranis

Sky

Chalchiuhtlicue

Sobek/Tefnut/N

un

Varuna

Lir

Water/seas/oceans/

rivers

Toci/Ciuatcoatl

Tonantzin Tlalli

Heket/Mut

Tawaret/Mesene

t

Durga/ Bhmi

Danu (Anu)*

Child Birth/

Mother Goddess

Quetzalcoatl

Shu

Varuna

Gaoth/Gwynt

Air

Tlaloc

Tefnut

Danu

Danu

Moisture

Metzli/

Coyolxauhqui

Khons/Khonsu/

Thoth

/Osiris/Min?Du

au

Dia Tuan

Moon

Xiuhtecutli

Mixcoatl/Huehuet

oatl

Seth

Agni

Brigit

Fire

Xipe Totec

Teteoinnan

Mictlantecuhtli/C

oatlique

Tezcatlipoca/

Tlaloc/Tlhahuizca

l-pantecuhtli

Discutable??

Chamunda

Taranis

Esus/Teutates/

Human Sacrifice

* Alternate Appellations Originated with Aryan culture gave name to rivers such as

Danube and Don.

Note the association between birth, fertility and serpents.

28

APPENDIX B

Aztec

Direction

Color

Avatar

Essence

Deity

North Black Smoking Mirror Evil Power Tezcatlipoca

South/Left Blue Hummingbird Warfare Huitzilopochtli

East Red rebirth Xipe Totec

West White Winged Serpent Wind Quetzalcoatl

Hindu Lokaplas

North

Yellow

Mongoose

Wealth

Kubera

South

Red

Sword

Death/Justice

Yama

East

Green

Pipa

God of Devas

Indra

West

White

Serpent

Oceans

Varuna

Daoism human names

Japanese and Chinese

North

Black

Tortoise

Water/Winter

Zhi Ming

Genbu/ Xunw

South

Vermillion

Bird

Fire/Summer

Ling Guang

Suzaku/ Zhqu

East

Azure

Dragon

Wood/Spring

Meng Zhang

Seiry Qnglng

West

White

Tiger

Metal/Autumn

Jian Bing

Byakko/ Bih

Center

Yellow

Dragon

Earth/Changing

Seasons

ry/ Hunglng

Kry

You might also like

- The Classic Maya Ceremonial Bar: An Iconographic AnalysisDocument39 pagesThe Classic Maya Ceremonial Bar: An Iconographic AnalysisCe Ácatl Topiltzin QuetzalcóatlNo ratings yet

- ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEYDocument82 pagesANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEYKessel WilliamNo ratings yet

- Statement On Akaxe Yotzin and IxpahuatzinDocument4 pagesStatement On Akaxe Yotzin and IxpahuatzinMexica UprisingNo ratings yet

- Lords of The NightDocument2 pagesLords of The NightAsdf JmasewqNo ratings yet

- Aztec Religion EssayDocument4 pagesAztec Religion EssayGail BiggersNo ratings yet

- Anthropology 1170 Mesoamerican Writing S PDFDocument11 pagesAnthropology 1170 Mesoamerican Writing S PDFMiguel Pimenta-Silva100% (1)

- Egyptian Civilization: The Nile Dynastic Egypt Religion WritingDocument56 pagesEgyptian Civilization: The Nile Dynastic Egypt Religion WritingLerma Luluquisen MejiaNo ratings yet

- The Maya Chronicles Brinton's Library Of Aboriginal American Literature, Number 1From EverandThe Maya Chronicles Brinton's Library Of Aboriginal American Literature, Number 1Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- A Brief History of The Incas by Brien Foerster PDFDocument102 pagesA Brief History of The Incas by Brien Foerster PDFgallidanNo ratings yet

- The Stone Sculpture of Tenochtitlan ChanDocument757 pagesThe Stone Sculpture of Tenochtitlan ChanAlessia FrassaniNo ratings yet

- SPCAA - 28 - Parsons - The Origins of Maya Art PDFDocument228 pagesSPCAA - 28 - Parsons - The Origins of Maya Art PDFMarx Navarro CastilloNo ratings yet

- Algonquin Indian Tales by Young, Egerton R., 1840-1909Document120 pagesAlgonquin Indian Tales by Young, Egerton R., 1840-1909Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Cyphers - OlmecaDocument28 pagesCyphers - OlmecaDaniela Grimberg100% (1)

- Filth and Healing in Yucatan Interpretin PDFDocument14 pagesFilth and Healing in Yucatan Interpretin PDFTlilan WenNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bilbiography Olmec ArtDocument46 pagesAnnotated Bilbiography Olmec ArtFvg Fvg FvgNo ratings yet

- Montezuma An Epic on the Origin and Fate of the Aztec NationFrom EverandMontezuma An Epic on the Origin and Fate of the Aztec NationNo ratings yet

- The Siouan Indians by McGee, W. J. (William John), 1853-1912Document48 pagesThe Siouan Indians by McGee, W. J. (William John), 1853-1912Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Zapotecs - Princes, Priests, and PeasantsDocument353 pagesThe Zapotecs - Princes, Priests, and PeasantsAnonymous Ius28dGsE100% (3)

- Akbal Glyph Mesoamerican Symbolism Olmec and Maya Stross 1992Document26 pagesAkbal Glyph Mesoamerican Symbolism Olmec and Maya Stross 1992María José TorallaNo ratings yet

- Ancient Human Sacrifice: An OverviewDocument10 pagesAncient Human Sacrifice: An OverviewadimarinNo ratings yet

- Deities of The Ancient Maya WorkshopDocument34 pagesDeities of The Ancient Maya WorkshopJem Sandoval67% (3)

- Rituals of Power ... by Manuel HermannDocument27 pagesRituals of Power ... by Manuel HermannwibleywobleyNo ratings yet

- Aztec GodsDocument5 pagesAztec Godsh0a7c0k1e0r100% (10)

- Articulo. Corn Deities and The Complementary Male Female Principle Karen Bassie SweetDocument19 pagesArticulo. Corn Deities and The Complementary Male Female Principle Karen Bassie Sweetanmara19548649No ratings yet

- An Inconstant Landscape: The Maya Kingdom of El Zotz, GuatemalaFrom EverandAn Inconstant Landscape: The Maya Kingdom of El Zotz, GuatemalaThomas G. GarrisonNo ratings yet

- Archaeology and The Maritime History of Ancient Orissa PDFDocument12 pagesArchaeology and The Maritime History of Ancient Orissa PDFNibedit NahakNo ratings yet

- The Inca EXPODocument20 pagesThe Inca EXPOJean Jaramillo100% (1)

- Teasing The Turtle From Its Shell: AHK and MAHK in Maya Writing, by Marc ZenderDocument14 pagesTeasing The Turtle From Its Shell: AHK and MAHK in Maya Writing, by Marc ZenderMuzen DerNo ratings yet

- Thunderbird (Mythology) - WikipediaDocument9 pagesThunderbird (Mythology) - WikipediaHugo García ManríquezNo ratings yet

- Xbalanque's Marriage ExploredDocument442 pagesXbalanque's Marriage Explored21Tauri100% (1)

- Blood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFDocument26 pagesBlood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFIsus DaviNo ratings yet

- Pachamama Encyclopedia of Latin AmericanDocument10 pagesPachamama Encyclopedia of Latin AmericanLuis Angel De La FlorNo ratings yet

- Viracocha Kukulkan QuetzalcoatlDocument15 pagesViracocha Kukulkan QuetzalcoatlRajendran NarayananNo ratings yet

- Out of India Theory: By: Vikraant V. SinghDocument12 pagesOut of India Theory: By: Vikraant V. SinghVikraant Singh100% (1)

- Meaning of Mayan NawalsDocument20 pagesMeaning of Mayan NawalsJosh MacLeodNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Religion and Cultural Performance in the New Maya WorldFrom EverandIndigenous Religion and Cultural Performance in the New Maya WorldNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Mythology PDFDocument43 pagesThe Origins of Mythology PDFТомислав Галавић100% (1)

- Rig Veda AmericanusDocument120 pagesRig Veda AmericanusLibros de Baubo100% (1)

- Culture of The Oceti SakowinDocument5 pagesCulture of The Oceti Sakowinapi-347721265No ratings yet

- The Shark-Monster's Role in Early Olmec Iconography and MythologyDocument38 pagesThe Shark-Monster's Role in Early Olmec Iconography and MythologyKevin Kirby100% (1)

- Galactic ButterflyDocument27 pagesGalactic Butterflyquick0No ratings yet

- Maya CosmologyDocument7 pagesMaya CosmologyBodibodiNo ratings yet

- Hymn To The Goddess AnnaDocument12 pagesHymn To The Goddess AnnaTorsten SchwankeNo ratings yet

- A Genetical Study of Human MigrationDocument8 pagesA Genetical Study of Human MigrationPremendra PriyadarshiNo ratings yet

- FENTON, WILLIAM N. - Iroquois Journey, An Anthropologist Remembers. (2007)Document224 pagesFENTON, WILLIAM N. - Iroquois Journey, An Anthropologist Remembers. (2007)Utentes BlxNo ratings yet

- OlmecsDocument7 pagesOlmecsapi-2699183740% (1)

- Vedic Roots of Tamil CultureDocument13 pagesVedic Roots of Tamil CultureRavi SoniNo ratings yet

- Star ScholarDocument16 pagesStar ScholarMatthew SaintNo ratings yet

- Ancient Mexican Astronomy Device Myth DebunkedDocument7 pagesAncient Mexican Astronomy Device Myth DebunkedMaarten JansenNo ratings yet

- The Wild: Which Employ Some Ex The ExDocument69 pagesThe Wild: Which Employ Some Ex The ExRussell Hartill100% (1)

- Rig Veda Americanus Sacred Songs of The Ancient Mexicans, With A Gloss in Nahuatl by VariousDocument67 pagesRig Veda Americanus Sacred Songs of The Ancient Mexicans, With A Gloss in Nahuatl by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- ElamDocument11 pagesElamAakashParan100% (1)

- Buddhism & Hinduism Premium Collection: The Light of Asia + The Essence of Buddhism + The Song Celestial (Bhagavad-Gita) + Hindu Literature + Indian Poetry (Unabridged): Religious Studies, Spiritual Poems & Sacred WritingsFrom EverandBuddhism & Hinduism Premium Collection: The Light of Asia + The Essence of Buddhism + The Song Celestial (Bhagavad-Gita) + Hindu Literature + Indian Poetry (Unabridged): Religious Studies, Spiritual Poems & Sacred WritingsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Ancient Civilizations Americas: of ThjeDocument8 pagesAncient Civilizations Americas: of ThjeJonathan100% (1)

- Shakti Puja Kali Worship in Trinidad 201 PDFDocument8 pagesShakti Puja Kali Worship in Trinidad 201 PDFAc RaviNo ratings yet

- The Noble SavageDocument3 pagesThe Noble SavageromrasNo ratings yet

- Wade - The Menzies World Map, A CritiqueDocument8 pagesWade - The Menzies World Map, A CritiqueVirgileNo ratings yet

- The French Presidency A School For ScandalDocument4 pagesThe French Presidency A School For ScandalromrasNo ratings yet

- Charite and PolydorusDocument139 pagesCharite and PolydorusromrasNo ratings yet

- Richard Hakluyt Discourse of Western Planting 1584Document2 pagesRichard Hakluyt Discourse of Western Planting 1584romrasNo ratings yet

- Aihwa Ong - Experiments With Freedom. Milieus of The HumanDocument17 pagesAihwa Ong - Experiments With Freedom. Milieus of The HumanromrasNo ratings yet

- Meriwether Lewis Intrepid ExplorerDocument4 pagesMeriwether Lewis Intrepid ExplorerromrasNo ratings yet

- Anacharsis ClootsDocument914 pagesAnacharsis ClootsromrasNo ratings yet

- The Dahomey AmazonsDocument6 pagesThe Dahomey AmazonsromrasNo ratings yet

- Magyar Genetika Hungarian GeneticsDocument30 pagesMagyar Genetika Hungarian GeneticsMinică GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Re Imagining IndiansDocument191 pagesRe Imagining IndiansromrasNo ratings yet

- The Travels of AnacharsisDocument585 pagesThe Travels of AnacharsisromrasNo ratings yet

- Frithjof Schuon's PaintingsDocument4 pagesFrithjof Schuon's PaintingsromrasNo ratings yet

- Wenamen's JourneyDocument12 pagesWenamen's JourneyromrasNo ratings yet

- Vivre Comme Frères. Native-French Alliances in The ST Lawrence Valley 1535-1667Document640 pagesVivre Comme Frères. Native-French Alliances in The ST Lawrence Valley 1535-1667romrasNo ratings yet

- Indigenism, Anarchism, FeminismDocument22 pagesIndigenism, Anarchism, FeminismromrasNo ratings yet

- Carpatho Danubian Genetic Ancestry in Central Asia PDFDocument1 pageCarpatho Danubian Genetic Ancestry in Central Asia PDFromrasNo ratings yet

- Poetry by Frithjof SchuonDocument5 pagesPoetry by Frithjof SchuonromrasNo ratings yet

- A History of Ancient GreeceDocument65 pagesA History of Ancient Greeceromras100% (5)

- On Frithjof Schuon's PaintingsDocument3 pagesOn Frithjof Schuon's PaintingsromrasNo ratings yet

- Nanjing Massacre OBSERVATIONS ON THE FILM JOHN RABEDocument7 pagesNanjing Massacre OBSERVATIONS ON THE FILM JOHN RABEsupernewnew100% (1)

- Frithjof Schuon - Religio PerennisDocument10 pagesFrithjof Schuon - Religio PerennisenigmarahasiaNo ratings yet

- Walcot Greek Envy CH 1 3Document20 pagesWalcot Greek Envy CH 1 3romrasNo ratings yet

- A History of Ancient GreeceDocument65 pagesA History of Ancient Greeceromras100% (5)

- The Dahomey AmazonsDocument6 pagesThe Dahomey AmazonsromrasNo ratings yet

- Indigenism, Anarchism, FeminismDocument22 pagesIndigenism, Anarchism, FeminismromrasNo ratings yet

- The Rabbi's WellDocument18 pagesThe Rabbi's WellromrasNo ratings yet

- Tom Hunter - The Ramayana in IndonesiaDocument4 pagesTom Hunter - The Ramayana in IndonesiaromrasNo ratings yet

- Donald A Mackenzie-Indian Myth and LegendDocument548 pagesDonald A Mackenzie-Indian Myth and LegendlimshakerNo ratings yet

- The Hidden History of The Incredibly Evil Khazarian MafiaDocument20 pagesThe Hidden History of The Incredibly Evil Khazarian MafiaQuiztronNo ratings yet

- Toyota Forklift 8hbw23 Service ManualDocument22 pagesToyota Forklift 8hbw23 Service Manualdavidbarton170301cqn99% (117)

- Instant Download Choices in Relationships An Introduction To Marriage and The Family 10th Edition Knox Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Choices in Relationships An Introduction To Marriage and The Family 10th Edition Knox Test Bank PDF Full ChapterBrianHudsonoqer100% (7)

- Finite Element Method Basic Concepts and Applications With Matlab Maple and Comsol 3rd Pepper Solution ManualDocument33 pagesFinite Element Method Basic Concepts and Applications With Matlab Maple and Comsol 3rd Pepper Solution Manualneighhyena.nizqtNo ratings yet

- North American Indian Beliefs and PracticesDocument3 pagesNorth American Indian Beliefs and PracticesJim HeffernanNo ratings yet

- Prisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia Prisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia PDFDocument30 pagesPrisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia Prisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia PDFmark_schwartz_41No ratings yet

- Where Do The They Rest - 1995Document40 pagesWhere Do The They Rest - 1995Roman Cerna MantillaNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Human SacrificeDocument4 pagesSymbolic Human SacrificeRemus TuckerNo ratings yet

- FvFargas - Treatise On Satanic Worship and Ritual Practice Vol IDocument73 pagesFvFargas - Treatise On Satanic Worship and Ritual Practice Vol IFvFargas100% (1)

- Full Download Essentials of Marketing A Marketing Strategy Planning Approach 15th Edition Perreault Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Essentials of Marketing A Marketing Strategy Planning Approach 15th Edition Perreault Test Bankparterre.firkinm7ke100% (27)

- Test Bank For Employment and Labor Law 9th EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Employment and Labor Law 9th Editionasiatic.arterym39s6No ratings yet

- VampDocument101 pagesVampFernando WagnerNo ratings yet

- The Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureDocument21 pagesThe Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureMerveNo ratings yet

- On the Burial of Unchaste Vestal VirginsDocument15 pagesOn the Burial of Unchaste Vestal VirginsRaicea IonutNo ratings yet

- Inman - Ancient Faiths and ModernDocument544 pagesInman - Ancient Faiths and ModernCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (7)

- Sam Harris.Document6 pagesSam Harris.kennedykioko01No ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece PDFDocument25 pagesHuman Sacrifice in Ancient Greece PDFRallyPierceNo ratings yet

- The Sacrifice of the Firstborn in the Hebrew BibleDocument328 pagesThe Sacrifice of the Firstborn in the Hebrew BibleFrankNo ratings yet

- 1d100plus Magic EventsDocument5 pages1d100plus Magic EventsAizatNo ratings yet

- History EssasyDocument5 pagesHistory EssasyKarin TanNo ratings yet

- The DruidsDocument36 pagesThe DruidsMizaa ÖöNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric Religion: General CharacteristicsDocument10 pagesPrehistoric Religion: General CharacteristicsLord PindarNo ratings yet

- Full Download Horngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis Canadian 8th Edition Datar Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Horngrens Cost Accounting A Managerial Emphasis Canadian 8th Edition Datar Test Bank PDF Full Chapterdominiecabasfsa28100% (13)

- Ritual and Metaphor Sacrifice in The Bible - Christian A. EberhartDocument193 pagesRitual and Metaphor Sacrifice in The Bible - Christian A. EberhartCarlos Alexandre CostaNo ratings yet

- Valerio Valeri, Wild VictimsDocument31 pagesValerio Valeri, Wild VictimselenaNo ratings yet

- The Satanic CalendarDocument6 pagesThe Satanic Calendarisher33% (3)

- Hyundai Solati h350 2019 Electrical Wiring DiagramDocument22 pagesHyundai Solati h350 2019 Electrical Wiring Diagramannaallen040593ycp100% (67)

- Full Download Test Bank For Introduction To General Organic and Biochemistry 12th Edition Frederick A Bettelheim William H Brown Mary K Campbell Shawn o Farrell Omar Torres 13 PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Introduction To General Organic and Biochemistry 12th Edition Frederick A Bettelheim William H Brown Mary K Campbell Shawn o Farrell Omar Torres 13 PDF Full Chaptercooly.maharmahb89a8100% (17)

- Balefire 2 eDocument85 pagesBalefire 2 eAsteria BooksNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice at ParbanhanDocument31 pagesHuman Sacrifice at ParbanhanpgandzNo ratings yet