Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Labor CD 06 Ed.

Uploaded by

JP Jayson Tefora Tabios0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

50 views45 pageslabor

Original Title

labor cd 06 ed.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentlabor

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

50 views45 pagesLabor CD 06 Ed.

Uploaded by

JP Jayson Tefora Tabioslabor

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 45

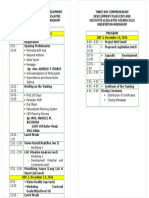

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Employer-Employee Relationship-

Control Test:

G.R. No. 138051. June 10, 2004.

JOSE SONZA vs. ABS-CBN

BROADCASTING CORPORATION,

Facts: In May 1994, respondent ABS-CBN

Broadcasting Corporation (ABS-CBN)

signed an Agreement with the Mel and Jay

Management and Development Corporation

(MJMDC). ABS-CBN was represented by its

corporate ofcers while MJMDC was

represented by Sonza, as President and

General Manager, and Tiangco, as EVP and

Treasurer. Referred to in the Agreement as

AGENT, MJMDC agreed to provide Sonzas

services exclusively to ABS-CBN as talent

for radio and television.

In April 1996, Sonza irrevocably

resigned in view of recent events concerning

his programs and career. He thereafter fled

a complain against ABS-CBN before the

Department of Labor and Employment.

Sonza complained that ABS-CBN did not

pay his salaries, separation pay, service

incentive leave pay, 13

th

month pay, signing

bonus, travel allowance and amounts due

under the Employees Stock Option Plan.

ABS-CBN fled a Motion to Dismiss

on the ground that no employer-employee

relationship existed between the parties.

The Labor Arbiter denied it and directed the

parties to fle their respective position

papers. He then considered the case

submitted for resolution and rendered

decision dismissing the complaint for lack

of jurisdiction.

Sonza appealed to the NLRC which

afrmed the Labor Arbiters decision. Sonza

fled a motion for reconsideration, which

the NLRC denied.

He then fled a special civil action

for certiorari before the Court of Appeals

assailing the decision and resolution of the

NLRC. The Court of Appeals rendered a

decision dismissing the case. Hence, the

petition

Issue: Whether or not employer-employee

relationship existed between Sonza and

ABS-CBN.

Ruling: Existence of an employer-employee

relationship is a question of fact. Appellate

courts accord the factual fndings of the

Labor Arbiter and the NLRC not only

respect but also fnality when supported by

substantial evidence. Court does not

substitute its own judgment for that of the

tribunal in determining where the weight of

evidence lies or what evidence is credible.

Case law has consistently held that

the elements of an employer-employee

relationship are: (a) the selection and

engagement of the employee; (b) the

payment of wages; (c) the power of

dismissal; and (d) the employers power to

control the employee on the means and

methods by which the work is

accomplished. The last element, the so-

called control test, is the most important

element.

The specifc selection and hiring of

Sonza, because of his unique skills, talent

and celebrity status not possessed by

ordinary employees, is a circumstance

indicative but not conclusive of independent

contractual relationship. The method of

selecting and engaging Sonza does not

conclusively determine his status.

All the talent fees and benefts paid

to Sonza were the result of negotiations

that led to the Agreement. If Sonza were

ABS-CBNs employee, there would be no

need for the parties to stipulate on benefts

such as SSS, Medicare, x x x and 13

th

month pay which the law automatically

incorporates into every employer-employee

contract. Whatever benefts Sonza enjoyed

arose from contract and not because of an

employer-employee relationship.

The power to bargain talent fees way

above the salary scales of ordinary

employees is a circumstance indicative, but

not conclusive, of an independent

contractual relationship.

Applying the control test to the

present case, the court found that Sonza is

not an employee but an independent

contractor. The control test is the most

important test our courts apply in

distinguishing an employee from an

independent contractor. This test is based

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

1

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

on the extent of control the hirer exercises

over a worker. The greater the supervision

and control the hirer exercises, the more

likely the worker is deemed an employee.

The converse holds true as well the less

control the hirer exercises, the more likely

the worker is considered an independent

contractor.

ABS-CBN did not exercise control

over the means and methods of

performance of Sonzas work. A radio

broadcast specialist who works under

minimal supervision is an independent

contractor. Being an exclusive talent does

not by itself mean that Sonza is an

employee of ABS-CBN. Even an

independent contractor can validly provide

his services exclusively to the hiring party.

In the broadcast industry, exclusivity is not

necessarily the same as control.

A mere executive issuance cannot

exclude independent contractors from the

class of service providers to the broadcast

industry. The classifcation of workers in

the broadcast industry into only two groups

under Policy Instruction No. 40 is not

binding on the courts, especially when the

classifcation has no basis either in law or

in fact.

The right of labor to security of

tenure as guaranteed in the Constitution

arises only if there is an employer-employee

relationship under labor laws. Not every

performance of services for a fee creates an

employer-employee relationship.

The Labor Arbiter can decide a case

based solely on the position papers and the

supporting documents without a formal

trial. The holding of a formal hearing or

trial is something that the parties cannot

demand as a matter of right. Subject to the

requirements of due process, the

technicalities of law and the rules obtaining

in the courts do not strictly apply in

proceedings before a Labor Arbiter.

Petition is DENIED.

EMPERMACO B. ABANTE, JR. vs.

LAMADRID BEARING & PARTS CORP.

and JOSE LAMADRID, President

G.R. No. 159890. May 28, 2004

Facts: Petitioner was employed by

respondent company Lamadrid Bearing and

Parts Corporation sometime in June 1985

as a salesman earning a commission of 3%

of the total paid-up sales covering the whole

area of Mindanao. His average monthly

income was more or less P16,000.00, but

later was increased to approximately

P20,269.50. Aside from selling the

merchandise of respondent corporation, he

was also tasked to collect payments from

his various customers.

Sometime in 1998, petitioner

encountered fve customers/clients with

bad accounts. Petitioner was confronted by

respondent Lamadrid over the bad

accounts and warned that if he does not

issue his own checks to cover the said bad

accounts, his commissions will not be

released and he will lose his job. He issued

his personal checks in favor of respondent

corporation on condition that the same

shall not be deposited for clearing and that

they shall be ofset against his periodic

commissions.

Contrary to their agreement,

respondent deposited the remaining checks

which were dishonored by the drawee bank

due to Account Closed.

On March 22, 2001, counsel for

respondent corporation sent a letter to

petitioner demanding that he make good

the dishonored checks or pay their cash

equivalent.

While doing his usual rounds as

commission salesman, petitioner was

handed by his customers a letter from the

respondent company warning them not to

deal with petitioner since it no longer

recognized him as a commission salesman.

Petitioner thus fled a complaint for

illegal dismissal with money claims against

respondent company and its president,

Jose Lamadrid, before the NLRC Regional

Arbitration Branch No. XI, Davao City.

By way of defense, respondents

countered that petitioner was not its

employee but a freelance salesman on

commission basis, procuring and

purchasing auto parts and supplies from

the latter on credit, consignment and

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

2

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

installment basis and selling the same to

his customers for proft and commission of

3% out of his total paid-up sales.

Finding no necessity for further

hearing the case after the parties submitted

their respective position papers, the Labor

Arbiter rendered a decision declaring

respondents Lamadrid Bearing & Parts

Corp. and Jose Lamadrid to pay jointly and

severally complainant EMPERMACO B.

ABANTE, JR. P1,336,729.62 representing

his awarded separation pay, back wages

(partial) unpaid commissions, refund of

deductions, damages and attorneys fees.

National Labor Relations

Commission reversed the decision of the

Labor Arbiter and dismissed the instant

case for lack of cause of action.

Court of Appeals denied the petition

of petitioner Abante.

Issue: Whether or not the petitioner is an

employee of respondent corporation.

Ruling: To ascertain the existence of an

employer-employee relationship,

jurisprudence has invariably applied the

four-fold test, namely: (1) the manner of

selection and engagement; (2) the payment

of wages; (3) the presence or absence of the

power of dismissal; and (4) the presence or

absence of the power of control. Of these

four, the last one is the most important.

The so-called control test is

commonly regarded as the most crucial and

determinative indicator of the presence or

absence of an employer-employee

relationship. Under the control test, an

employer-employee relationship exists

where the person for whom the services are

performed reserves the right to control not

only the end achieved, but also the manner

and means to be used in reaching that end.

Applying the aforementioned test, an

employer-employee relationship is notably

absent in this case. It is undisputed that

petitioner Abante was a commission

salesman who received 3% commission of

his gross sales. Yet no quota was imposed

on him by the respondent; such that a

dismal performance or even a dead result

will not result in any sanction or provide a

ground for dismissal. He was not required

to report to the ofce at any time or submit

any periodic written report on his sales

performance and activities. Although he

had the whole of Mindanao as his base of

operation, he was not designated by

respondent to conduct his sales activities at

any particular or specifc place. He

pursued his selling activities without

interference or supervision from respondent

company and relied on his own resources to

perform his functions. Respondent

company did not prescribe the manner of

selling the merchandise; he was left alone

to adopt any style or strategy to entice his

customers.

While it is true that he occasionally

reported to the Manila ofce to attend

conferences on marketing strategies, it was

intended not to control the manner and

means to be used in reaching the desired

end, but to serve as a guide and to upgrade

his skills for a more efcient marketing

performance. As correctly observed by the

appellate court, reports on sales, collection,

competitors, market strategies, price

listings and new ofers relayed by petitioner

during his conferences to Manila do not

indicate that he was under the control of

respondent.

Moreover, petitioner was free to ofer

his services to other companies engaged in

similar or related marketing activities as

evidenced by the certifcations issued by

various customers.

The decision of Court of Appeals

was afrmed.

Regular Employee:

MITSUBISHI MOTORS vs. CHRYSLER

PHILIPPINES

G.R. No. 148738

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

3

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Facts: Nelson Paras was hired by MMPC

(Mitsubishi Motors Philippines

Corporation) on probationary basis.

He started reporting to work on May

27, 1996. He was later evaluated by

his immediate supervisors and

received an average rating. He was

informed that based on his

performance, he would be

regularized.

However, the Division and Department

managers together with his immediate

supervisors reviewed the performance and

unanimously agreed that the performance

was unsatisfactory. As a consequence,

Paras was not regularized. On November

26, 1996, he received a notice of

termination dated November 25, 1996

informing him that his services were

terminated efective said date since he

failed to meet the required company

standards for regularization.i

The labor union demanded the

settlement of the dispute. It posited that

Paras was dismissed on his one hundred

eighty third (183

rd

) day of employment, or

three days after the expiration of the

probationary period of 6 months. It was

contended that Paras was already a regular

employee on the date of the termination of

his probationary employment.

Issue: Whether or not Paras was a regular

employee when served the notice of

termination

Ruling: Applying Article 13 of the Civil

Code, the probationary period of six

(6) months consists of one hundred

eighty (180) days. This is in

conformity with paragraph one,

Article 13 of the Civil Code which

provides that the months which are

not designated by their names shall

be understood as consisting of thirty

(30) days each. The number of

months in the probationary period,

six months should then be multiplied

by the number of days within a

month, thirty days; hence, the period

of one hundred eighty days. As clearly

provided for in the last paragraph of

article 13, in computing the period,

the frst day shall be excluded and the

last day included. Thus, the 180 days

commenced o may 27, 1996 and

ended on November 23, 2996. The

termination letter dated November 25,

1996 was served on November 26,

1996. He was, by then, a regular

employee of the petitioner.

MANILA WATER CO. V. PENA

434 SCRA 53

Facts: Manila Water Co. undertook to

absorb former employees of the MWSS

whose names and positions were in the

list furnished by MWSS, while the

employment of those not in the list was

terminated on the day MWC took over

the operations of the East zone.

Respondents, being contractual

collectors of the MWSS, were among the

121 employees not included in the list,

nevertheless, petitioners engaged their

services without written contract.

The 121 collectors incorporated the

AGCI, which was contracted by petitioner to

collect charges for the Balara branch.

Later on, petitioner terminated its

contract with AGCI.

Respondents fled a complaint for

illegal dismissal, contending that they were

petitioners employees as all the methods

and procedures of their collection were

controlled by the latter.

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

4

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

The labor arbiter rendered a

decision fnding the dismissal of

respondents illegal.

Issue: Whether or not there exists an

employer-employee relationship

between petitioner and respondents.

Held: AGCI was not an independent

contractor. AGCI does not have

substantial capitalization or

investment in the form of tools,

equipment, machineries, work

premises, and other materials to

qualify as an independent contractor.

The work of the respondents was

directly related to the principal business or

operation of the petitioner.

AGCI did not carry on an

independent business or undertake the

performance of its service contract

according to its own manner and method,

free from the control and supervision of its

principal, the petitioner.

Therefore, there exists an employer-

employee relationship.

Employment Contract, Period :

Pangilinan vs. General Milling

Corporation

GR No. 149329-July 12, 2004

Facts: Petitioners were employed by

respondent as casual employee to work on

one of its poultry plant in Rizal. They have

signed under separate temporary / casual

contracts of employment, for a period of 5

months.

Upon the expiration of their

contracts, petitioners were terminated;

hence they fled an illegal dismissal case

against GMC alleging that they were already

regular employee at the time of their

separation. Moreover, their work is usual &

necessary to the mainline of business; as

such they can be considered regular and

cannot be terminated without just cause or

notice thereof. Employer ruled in favor of

GMC. Thus this petition

Issue: Whether or not petitioners can be

considered a regular employee at the time of

there separation.

Held: The petition is bereft of merit. Article

280 of the Labor Code, does not proscribe

or prohibit an employment contract with

fxed period. They are binding & valid,

provided it was entered voluntarily &

knowingly without coercion. A contract of

employment for a defnite period terminates

by its own term at the end of such period.

Independent Contractor:

MANILA WATER CO. V. PENA

434 SCRA 53

Facts: Manila Water Co. undertook to

absorb former employees of the MWSS

whose names and positions were in the

list furnished by MWSS, while the

employment of those not in the list was

terminated on the day MWC took over

the operations of the East zone.

Respondents, being contractual

collectors of the MWSS, were among the

121 employees not included in the list,

nevertheless, petitioners engaged their

services without written contract.

The 121 collectors incorporated the

AGCI, which was contracted by petitioner to

collect charges for the Balara branch.

Later on, petitioner terminated its

contract with AGCI.

Respondents fled a complaint for

illegal dismissal, contending that they were

petitioners employees as all the methods

and procedures of their collection were

controlled by the latter.

The labor arbiter rendered a

decision fnding the dismissal of

respondents illegal.

Issue: Whether or not there exists an

employer-employee relationship

between petitioner and respondents.

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

5

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Held: AGCI was not an independent

contractor. AGCI does not have

substantial capitalization or

investment in the form of tools,

equipment, machineries, work

premises, and other materials to

qualify as an independent contractor.

The work of the respondents was

directly related to the principal business or

operation of the petitioner.

AGCI did not carry on an

independent business or undertake the

performance of its service contract

according to its own manner and

method, free from the control and

supervision of its principal, the

petitioner.

Therefore, there exists an employer-

employee relationship.

Dismissal:

BOLINAO SECURITY AND

INVESTIGATION SERVICE, INC. vs.

ARSENIO M. TOSTON

G.R. No. 139135. January 29, 2004

Facts: Respondent Arsenio M. Toston, was

employed as a security guard by Bolinao

Security and Investigation Service, Inc.,

with a monthly salary of P5,000.00.On

August 17, 1995 due to a gunshot wound

he sustained from his co-security guard. He

fled an application for one-month leave of

absence. He also claimed and/ or medical

benefts. While petitioner approved his one-

month LOA his claim for the benefts were

rejected. He found out however that the

petitioner failed to remit it monthly

contributions for nine (9) consecutive

months. He then reported this to SSS.

On September 15, 1995, Lucy Caasi,

in-charge of remitting petitioners

contributions to the SSS, scolded and

rebuked respondent and told him not to

report for work and that his name would be

dropped from the rolls.

On September 29, 1995, respondent

fled with the Labor Arbiter a complaint

against petitioner and its president, for

illegal dismissal and non-payment of wages

and other benefts, with prayer for

reinstatement and payment of full back

wages. The Labor Arbiter rendered decision

in favor of the respondent.

Upon appeal, NLRC promulgated a

decision afrming with modifcation the

Arbiters assailed Decision in the sense that

the award of moral and exemplary damages

was deleted. The Court of Appeals also

afrmed the decision of the NLRC.

Hence this appeal.

Issue: Whether or not respondent Toston

was illegally dismissed?

Held: In the case at bar, there is no

showing of a clear, valid and legal cause

which justifes respondents removal from

employment. Neither did petitioner serve

two written notices to respondent prior to

his termination from employment as

required by the Labor Code. Clearly, this is

a case of illegal dismissal.

It is a settled doctrine that the

employer has the burden of proving the

lawfulness of his employees dismissal. The

validity of the charge must be clearly

established in a manner consistent with

due process. The Implementing Rules of

the Labor Code provide that no worker shall

be dismissed except for a just or authorized

cause provided by law and after due

process. This provision has two aspects: (1)

the legality of the act of dismissal, that is,

dismissal based on the grounds provided by

Article 282 of the Labor Code, and (2) the

legality in the manner of dismissal. The

illegality of the act of dismissal constitutes

discharge without just cause, while

illegality in the manner of dismissal is

dismissal without due process. Clearly,

petitioner failed to discharge its burden.

Respondent who was illegally

dismissed from work is actually entitled to

reinstatement without loss of seniority

rights and other privileges as well as to his

full backwages, inclusive of allowances, and

to other benefts or their monetary

equivalent computed from the time his

compensation was withheld from him up to

the time of his actual reinstatement.

However, the circumstances obtaining

in this case do not warrant the

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

6

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

reinstatement of respondent. Apparently,

antagonism caused a severe strain in the

relationship between him and petitioner

company. A more equitable disposition

would be an award of separation pay

equivalent to at least one month pay, or one

month pay for every year of service,

whichever is higher (with a fraction of at

least six (6) months being considered as

one (1) whole year), in addition to his full

backwages, allowances and other benefts

Records show that respondent was

employed from March 1993 to September

15, 1995, or for two (2) years and six (6)

months, with a monthly salary of

P5,000.00. Hence, he is entitled to a

separation pay of P15,000.00.

The assailed decision and resolution of

the Court of Appeals are hereby AFFIRMED

WITH MODIFICATION in the sense that, in

lieu of reinstatement, respondent is

awarded separation pay equivalent to P15,

000.00; and his full backwages, other

privileges and benefts, or their monetary

equivalent during the period of his

dismissal up to his supposed actual

reinstatement.Costs against petitioner.

GALLERA DE GUISON HERMANOS INC. v.

CRUZ

June 10, 2004

Facts: Private respondent Cruz was a

cashier and stockholder of Petitioner

Gallera de Guison Hermanos, Inc. since

1976. On February 15, 1998, private

respondent wrote Gallera requesting that

she be assigned as Liaison Ofcer, which is

a more challenging job than as a cashier.

Atty. Sumawang, Galleras counsel, replied

to her than the Board is not in a legal

position to consider the request because an

employee cannot be appointed to another

position which would result in the

reduction of his existing salary and that the

duties and responsibilities of a Liaison

Ofcer are already being performed by

some of the management staf.

Subsequently, due to the alleged ill

treatment and harassment perpetrated by

Galeras management against the private

respondent, the latter procured a medical

certifcate and went on sick leave. While on

leave, petitioners appointed one relative of

the Cruz, as cashier. Meanwhile, Atty.

Sumawang; wrote private respondent

advising her that upon her return to work

she shall cease and desist from occupying

and performing the duties of cashier and

instead she shall report for work on a no

work no pay basis in the meantime that the

management is studying to which position

she will be transferred. Eventually, she was

designated as liaison ofcer. However, one

day, due to her absence on the said date,

the salary of Cruz was withheld. Her

designation as liaison ofcer in the payroll

on even date was likewise removed.

Thereafter, the private respondent did not

report for work. Despite ofers from Gallera

for her to return, on a no work, no pay

basis, except the allowances and other

cash entitlements to the position, Cruz fle

with DOLE a complaint for illegal dismissal.

The labor arbiter issued a decision

declaring private respondent to have been

illegally dismissed by petitioners. The

petitioners then fled a petition for certiorari

with the CA which dismissed the petition

ruling that contrary to the petitioners

contention that respondent resigned from

her position as cashier, the latter was

actually removed from her position by the

petitioners. Subsequently, the petitioners

appointed Cruz as liaison ofcer, a move

which entailed a demotion in her position

and diminution of salaries, privileges and

other benefts. Hence, the Court of Appeals

concluded that Cruz was constructively

dismissed and declared her entitled to

backwages, separation pay and attorneys

fees. The ofcers who consented to her

transfer were held solidarily liable with

Gallera.

Issue: Whether or not Cruz was

illegally dismissed

Held: The instant petition raises a

fundamental factual issue which has

already been exhaustively discussed and

passed upon by the Labor Arbiter and the

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

7

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Court of Appeals, i.e, whether Cruz was

dismissed for cause. The appellate court,

dismissing the petitioners petition for

certiorari assailing the NLRCs dismissal of

their appeal and upholding the decision of

the Labor Arbiter, ruled that Cruz was

illegally dismissed and the dismissal was

attended by bad faith on the part of the

petitioners; hence, the petitioners are

solidarily liable for Cruz monetary claims

consisting of separation pay, backwages

and attorneys fees.

It is notable to mention time and again the

much-repeated but not so well-heeded rule

that fndings of fact of the CA, particularly

where it is in absolute agreement with that

of the NLRC and the Labor Arbiter, as in

this case, are accorded not only respect but

even fnality and are deemed binding upon

this Court so long as they are supported by

substantial evidence.

ASUFRIN, JR. vs. SAN MIGUEL

CORPORATION

G.R. No. 156658 March 10, 2004

Facts: Coca-Cola Plant, then a department

of respondent SMC, hired the petitioner as

a utility/miscellaneous worker. He

subsequently became a regular employee

paid on a daily basis as a Forklift Operator.

He afterwards became a monthly paid

employee when he was promoted as a Stock

Clerk. When the sales ofce and operations

at the branch where the petitioner worked

were reorganized, several positions

including his was abolished. The company

upon reviewing his qualifcations then

designated the petitioner as a designated

checker at the sales ofce.

However, the real problem arose

when respondent SMC implemented a new

marketing system known as the pre-selling

scheme at the beer sales ofce. As a

consequence thereof, all position of route

sales and warehouse personnel were

declared redundant. The respondent

notifed the DOLE and the personnel

afected which includes the petitioner.

Thereafter, the employees whose positions

were declared redundant were informed

that they could avail of the respondent

corporations early retirement package

pursuant to the retrenchment program,

while those who will not avail of the same

will be redeployed or absorbed at other

ofces. Petitioner opted to remain and

manifested with the Acting Director his

intention to accept any job considering that

he has 3 children in college.

Petitioner was surprised however

later to fnd out that his name was included

in the list of those who accepted the early

retirement package. His request to be

assigned to any department and position

was ignored by the Acting Manager. This

prompted the petitioner to fle a complaint

for illegal dismissal against the SMC. The

Labor Arbiter dismissed the complaint and

upon appeal to the NLRC, the latter set

aside the decision of the Labor Arbiter. SMC

in turn appealed to the CA which reversed

the decision of the NLRC and reinstated the

decision of the Labor Arbiter and thus this

present case.

Issue: Whether or not the petitioners

dismissal is based on a just and authorized

cause

Held: The determination that the

employees services are no longer necessary

or sustainable and, therefore, properly

terminable is an exercise of business

judgment of the employer. The wisdom or

soundness of this judgment is not subject

to discretionary review of the Labor Arbiter

nor the NLRC, provided that there is no

violation of law and no showing that it was

prompted by an arbitrary or malicious act.

In other words, it is not enough for a

company to merely declare that it has been

overmanned. It must produce adequate

proof that such is the actual situation to

justify the dismissal of the afected

employees for redundancy.

Persuasive as the explanation given

by respondent to justify the dismissal, a

number of disturbing circumstances

however left the court unconvinced like the

ignorance of the corporation of the request

of the petitioner to be deployed in any

position, his being in another branchs

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

8

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

payroll, despite the shut down of the

warehousing operations, the ofce was still

used as a warehouse, and in selecting the

employees to be dismissed it appears that

no criterion was adopted by respondent.

It bears stressing that whether it be

redundancy or retrenchment or any of the

other authorized causes, no employee may

be dismissed without the observance of the

fundamentals of good faith. It is not

difcult for employers to abolish positions

in the guise of a cost-cutting measure and

we should not be easily swayed by such

schemes which are all too often to near

nothing what is left of rubble of rights of

our exploited workers. Given the nature of

the petitioners job as a Warehouse

Checker, it is inconceivable that the

respondent could not accommodate his

services considering that the Warehousing

operations have not shut down.

Thus, the dismissal of the petitioner

should be declared as illegal.

J.A.T. GENERAL SERVICES V. NLRC

421 SCRA 78

Facts: JAT is a single proprietorship

engaged in the business of selling

second hand heavy equipment. It hired

Jose Mascarinas as helper and tasked

to coordinate with the cleaning and

delivery of the heavy equipment sold to

customers.

The sales of heavy equipment

declined because of the Asian currency

crisis. JAT temporarily suspended its

operations. It advised its employees not to

report for work.

Mascarinas fled a case for illegal

dismissal before the NLRC.

JAT fled an Establishment

Termination with the DOLE, notifying the

latter of its decision to close its business

operations due to business losses and

fnancial reverses.

The labor arbiter rendered a

decision fnding the dismissal unjustifed

and ordering JAT to pay the respondent

separation pay and backwages.

The labor arbiter ruled that Mascarinas

dismissal was unjustifed because of

petitioners failure to serve upon the

respondent and the DOLE the required

written notice of termination at least one

month prior to the efectivity thereof and

to submit proof showing that petitioners

sufered a business slowdown in

operations and sales.

On appeal, the NLRC afrmed the

said decision.

Issue: Whether or not respondent was

illegally dismissed from employment

due to the closure of the petitioners

business.

Held: The Court afrmed the decision of

the CA, which upheld the decision of

the NLRC fnding that there was illegal

dismissal for failure to comply with the

requirement provided for by law.

While business reverses or losses

are recognized by law as an authorized

cause for terminating employment it is an

essential requirement that alleged losses in

business operations must be proven

convincingly.

Three requirements are necessary

for a valid cessation of business

operations, namely: a) service of a

written notice to the employees and to

the DOLE at least one month before the

intended date thereof; b) the cessation of

business must be bona fde in character;

and c) payment to the employees of the

termination pay amounting to at least

one-half month pay for every year of

service, or one month pay, whichever is

higher.

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

9

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Closure of business, as an

authorized cause for termination of

employment, aims to prevent further

fnancial drain upon an employer who

cannot pay anymore his employees since

business has already stopped.

RAMOS vs. COURT OF APPEALS

G.R. No. 145405

Facts: Petitioner was frst employed by

Union Bank as post audit clerk. He later

became a branch cashier and subsequently

as acting branch manager. During his

management, one Rudy Paras was assigned

as branch cashier. Thereafter, the Central

Accounting Division of the Bank reported

certain unreconciled statements amounting

to millions.

By the time of its discovery, Paras had

long resigned and could no longer be found.

Consequently, petitioner was dismissed

due to negligence/serious dereliction of

duty resulting in loss of trust and

confdence by management.

Petitioner fled an action for illegal

dismissal. The labor arbiter ruled in his

favor. However, it was reversed by NLRC and

afrmed by CA, hence the petition.

Issue: Whether or not the dismissal is

proper.

Ruling: To validly dismiss an employee

on the ground of loss of trust and

confdence, the following guidelines

must be followed:

1.the loss of confdence must

not be simulated;

2.it should not be used to

subterfuge for causes which

are illegal, improper or

unjustifed;

3.it may not be arbitrarily

asserted in the face of

overwhelming evidence to the

contrary;

4.it must be genuine, not a mere

afterthought, to justify earlier

action taken in bad faith;

5.the employee involved holds a

position of trust and

confdence

In the case at bar, petitioner held a

position of trust and confdence as the

regular branch cashier and acting branch

manager. He was utterly negligent in

performing his duties as acting branch

manager. The scam perpetrated could have

been easily detected had petitioner

conscientiously done his job in carefully

overseeing the operations. Union Bank

therefore had reason to lose trust and

confdence and to impose penalty of

dismissal on him.

ADELINO FELIX vs. NATIONAL LABOR

RELATIONS COMMISSION and REPUBLIC

ASAHI GLASS CORPORATION

G.R. No. 148256. November 17, 2004

Facts: Petitioner was hired by the company

as a Cadet Engineer and became a

supervisor, a position he held until January

1992.

In January 1992, he was designated

as Marketing Ofcer II, a position at the

companys Fabricated Glass Division

Marketing (FGD Marketing).

As Marketing Ofcer II of the FGD

Marketing, the bulk of petitioners functions

is related to sales.

Sometime in July 1994, he was

asked by certain ofcers of the company to

resign and accept a separation package.

Petitioner refused to resign and accept

separation benefts.

He was not given work and another

employee, Tacata, was assigned to take over

his post and function.

He, through his lawyer, warned the

company about the illegality of its actions.

In replying to petitioners letter, the

company emphasized that given the series

of irresponsible and inefcient acts he had

committed justifed the initiation of an

administrative proceeding against him.

The company went on to declare

that it had fnally decided to initiate

disciplinary action against him in view of

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

10

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

his irresponsibility in sending the letter

which pre-empted management

prerogatives.

Thus the company directed

petitioner to explain in writing within 48

hours from receipt thereof why his services

should not be terminated for loss of trust

and confdence.

Petitioner denied the charges

against him, explaining that his absence for

6 days from May 29 to June 5, 1992 was

occasioned by some problems at home

which he had to personally attend to.

The company subsequently

terminated petitioners services for loss of

trust and confdence.

Petitioner lodged a complaint for

illegal dismissal.

Issue: Whether or not the companys loss of

trust and confdence in petitioner is

founded on facts established by substantial

and competent evidence

Held:No, The employer's evidence,

although not required to be of such degree

as that required in criminal cases, i.e.,

proof beyond reasonable doubt, must be

substantial.

It must clearly and convincingly

establish the facts upon which loss of

confdence in the employee is based.

In the case at bar, the company

failed to discharge this burden.

While the company complained of

petitioner having incurred 6 days of

absence without leave from May 29 to June

5, 1992, records do not disclose that

petitioner incurred any further absences

without leave.

More importantly, except for that

incident in 1992, the company failed to

show that there were instances during the

14 years that petitioner had been employed

that he incurred absences without leave.

The propriety of petitioners 6 days

of absence having priorly been settled by

the parties, the company may no longer ask

petitioner to, more than two years later, re-

explain his absence and use the same to

justify his dismissal.

As for the charge that petitioner had

not been attending the daily 3 minutes

meeting of the FGD Marketing, the

company took no action on the matter, nor

warned petitioner that his attendance in

the meetings was mandatory.

It was several months later when

the company frst called his attention to it

and used it as a basis for dismissing him.

A company is expected to call the

attention of an employee to any undesirable

act or omission within a reasonable time.

In the case at bar, the failure of the

company to timely take any disciplinary

action against petitioner weakens its claim

that petitioners continued absence in the

meetings rendered him unft for continued

employment with it.

That the company hastily dismissed

petitioner is clearly apparent. He was not

given adequate time to prepare for his

defense, but was peremptorily dismissed,

even without any formal investigation or

hearing.

Where the employee denies the

charges against him, a hearing is necessary

to thresh out any doubt. The failure of the

company to give petitioner, who denied the

charges against him, the beneft of a

hearing and an investigation before his

termination constitutes an infringement of

his constitutional right to due process.

As for the other two charges that

petitioner as a feld ofcer unnecessarily

lingered or killed time at the place of clients

and engaged them in arguments and

quarrels, and that he visited UMC

(Mandaluyong) only when called upon to do

so the company failed to substantiate the

same.

Tacatas (replacement of petitioner)

statement that Arnel Deunida [Supply

Superintendent of FMC] requested that our

customer service and QA Stafs resume

their regular visits to FMC to inspect and

evaluate glass rejects gives credence to the

allegation of petitioner that he regularly

visited his client and it was only in late July

1994 that he could no longer do so for

Tacata having taken over his position.

Petitioner had long been divested of

responsibility over these accounts when

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

11

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

complaints were documented by respondent

corporation.

As to the other complaints regarding

rejected glasses and returns due to

scratches, distortion, chipping and no-hole,

mispacking and handling procedure:

nowhere it is shown that petitioner was

directly responsible for the rejected glasses

and items.

Petitioners function at the FGD

Marketing was confned to sales.

Except for the mere allegation of

petitioners manager that its clients have

been complaining of petitioners work

attitude and performance, there is no

concrete evidence to show the same.

Absent any standard of performance

upon which petitioner was rated on the job,

loss of confdence has no basis.

Even if all the allegations-charges to

the petitioner are true, they are not of such

nature which merits the penalty of

dismissal, given petitioners service for 14

years.

Dismissal is unduly harsh and

grossly disproportionate to the charges; the

penalty imposed should be commensurate

to the gravity of his ofense.

An employer may terminate the

services of an employee due to loss of trust

and confdence; however, the loss must be

based not on ordinary breach by the latter

of the trust reposed in him by the former,

but, in the language of Article 28[2]c of the

Labor Code, on willful breach.

A breach is willful if it is done

intentionally, knowingly and purposely,

without justifable excuse, as distinguished

from an act done carelessly, thoughtlessly,

heedlessly or inadvertently.

Dismissal must rest on substantial

grounds and not on the employers

arbitrariness, whims, caprice or suspicion;

otherwise, the employee would eternally

remain at the mercy of the employer.

There must therefore be an actual

breach of duty committed by the employee

which must be established by substantial

evidence.

There being no basis in law or in

fact justifying petitioners dismissal on the

basis of loss of trust and confdence, his

dismissal was illegal.

PHILTREAD TIRE & RUBBER

CORPORATION, vs. ALBERTO VICENTE

G.R. No. 142759. November 10, 2004

Facts: Alberto M. Vicente, respondent, was

employed by Philtread Tire and Rubber

Corporation, petitioner. At the time of his

dismissal from the service, he was a

housekeeping coordinator at the General

Services Department, receiving a monthly

salary of P8,784.00. One of his duties was

to recommend to petitioner, for its approval,

projects intended for the beautifcation and

maintenance of its premises.

Engr. Ramon Y. Dumo, Administrative

Ofcer and Head of petitioners Security

and Safety Department, received a

complaint from Crisente Avis, a sign painter

with whom petitioner had a service

contract. Avis reported that he was being

forced by respondent to overprice by

P1,000.00 his service fee of P3,800.00 and

to deliver to him (respondent) the said

amount of P1,000.00; and that should Avis

fail to do so, he will no longer be awarded

future contracts.

Dumo conducted an investigation

attended by respondent, Avis, and three

representatives from the workers union.

Avis declared that sometime in January

1991, petitioner hired him to paint its trash

cans, push carts and cigarette waste boxes.

They agreed that his services will be paid

upon completion of the painting job and

submission of the corresponding invoice.

However, herein respondent instructed him

to prepare an invoice indicating therein that

his fee for his painting services is

P4,800.00, instead of P3,800.00.

Respondent even assured him that the

petitioner will approve the invoice.

At this juncture, petitioner assigned

respondent to perform janitorial duties,

prompting him to request an immediate

disposition of his case. But when

petitioner directed him to submit his

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

12

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

evidence within three (3) days from notice,

he failed to comply.

After evaluating the records on hand,

petitioner found respondent guilty of

extortion, fraud, serious misconduct and

willful breach of trust and confdence.

Petitioner then sent him a notice

terminating his services

Respondent fled with the Labor Arbiter

a complaint for illegal dismissal and

damages against petitioner and Engr.

Dumo. The Labor Arbiter dismissed

respondents complaint

Upon appeal, the National Labor

Relations Commission (NLRC) reversed the

Labor Arbiters assailed decision

Petitioner then fled a motion for

reconsideration but was denied by the

NLRC it fled with this Court a petition for

certiorari with prayer for the issuance of a

temporary restraining order.

The Appellate Court rendered a

Decision afrming the assailed Decision of

the NLRC. The petitioner fled a motion for

reconsideration, but was denied by the

Appellate Court

Held: The issue raised is factual. It is basic

that the fndings of fact by the Court of

Appeals, when supported by substantial

evidence, are conclusive and binding upon

the parties and are not reviewable by this

Court, unless the case falls under any of

the exceptions to the rule, such as when

the fndings by the Appellate Court are not

supported by evidence. This exception is

being relied upon by petitioner.

Here, there is neither direct nor

documentary evidence to prove that

respondent was involved in extortion it is

not clear that respondent urged or forced

Avis to increase his service fee by P1,000.00

and to give the amount to him

(respondent). In fact, Avis is not certain

whether respondent was really serious

when he allegedly told him (Avis) to increase

his service fee to P4,800.00. We thus hold

that petitioner failed to prove its charge by

substantial evidence. Substantial evidence

is that amount of relevant evidence which a

reasonable mind might accept as adequate

to justify a conclusion.

Respondent who was illegally

dismissed from work is entitled to

reinstatement without loss of seniority

rights, full back wages, inclusive of

allowances, and other benefts or their

monetary equivalent computed from the

time his compensation was withheld

from him up to the time of his actual

reinstatement.

However, the circumstances obtaining

in this case do not warrant the

reinstatement of respondent. Aside from

the fact that antagonism caused a severe

strain in the parties employer-employee

relationship, Petitioner Company has

completely ceased its tire manufacturing

and marketing operations

Hence, he is entitled to a separation

pay. Decision AFFIRMED with

MODIFICATION in the sense that, in lieu of

reinstatement, respondent is awarded

separation pay equivalent to P114, 192.00,

plus his full back wages, and other

privileges and benefts, or their monetary

equivalent, during the period of his

dismissal up to his supposed actual

reinstatement.

PHILIPPINE JOURNALISTS, INC. vs.

MICHAEL MOSQUEDA

G.R. No. 141430 May 7, 2004

Facts: Petitioner was sequestered by the

PCGG and by virtue of the writs of

sequestration issued by the Sandiganbayan,

PJI was placed under the management of

PCGG. Rosario Olivares, one of the

stockholders, attempted to regain control of

the PJI management. Separate stockholder

meetings were held, where each group

elected its own members to the Board of

Directors.

The Olivares Group passed

Resolution No. 92-2 designating Michael

Mosqueda, respondent, as Chairman of a

Task Force, along with fve (5) other

members, to protect the properties, funds

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

13

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

and assets of PJI and enforce or implement

directives, instructions and orders of the

Olivares group. Thereafter, Abraham J.

Buenaluz, Ofcer-in-charge of PJIs

Administrative Services Division, charged

them with "serious misconduct prejudicial

to the interest of the company and/or

present management; willful breach of trust

and confdence; confict of interest; and

disloyalty under the PJI Personnel

Handbook".

Petitioners new management placed

respondent and other members of the Task

Force under preventive suspension pending

the investigation of the formal charges

against them. Prior to the investigation, the

Journal Employees Union (Union), for and

in behalf of respondent and other members,

fled with the Labor Arbiter a complaint for

illegal suspension, unfair labor practice,

and damages against petitioner.

Upon recommendation of Ofcer-in-

charge Buenaluz, petitioner terminated the

services of respondent and the other

members of the Task Force. The Labor

Arbiter rendered a Decision holding that

respondent and the other fve employees

were illegally dismissed from employment

and ordering petitioner (1) to reinstate them

to their former positions and (2) to pay their

backwages and moral and exemplary

damages. The National Labor Relations

Commission afrmed the Arbiters decision

with modifcation. Respondent fled with

the Court of Appeals a petition for certiorari

assailing, as grave abuse of discretion, the

NLRCs deletion of the award of backwages,

damages and attorneys fees. The Court of

Appeals granted the petition and reinstated

the Arbiters award of damages. Petitioner

now comes to this Court via a petition for

review on certiorari

Issue: Whether or not the award of

damages is proper

Held: Under Art. 279 of the Labor Code, an

employee who is unjustly dismissed is

entitled to reinstatement, without loss of

seniority rights and other privileges, and to

the payment of his full backwages, inclusive

of allowances, and other benefts or their

monetary equivalent, computed from the

time his compensation was withheld from

him (which, as a rule, is from the time of

his illegal dismissal) up to the time of his

actual reinstatement.

The Court does not see any reason

to depart from the foregoing rule in the case

of herein respondent who, as held by three

(3) independent bodies, was illegally

dismissed, and thus, rightfully entitled to

an award of full backwages, inclusive of

allowances and other benefts or their

monetary equivalent, computed from March

10, 1992, the date of his illegal dismissal

(and not from March 11, 1992 as

erroneously held by the Court of Appeals)

up to the time of his actual reinstatement.

The decision is AFFIRMED with

MODIFICATION in the sense that

respondent is awarded his full backwages,

other privileges and benefts, or their

monetary equivalent corresponding to the

period of his dismissal from March 10,

1992 up to his actual reinstatement.

ACD Investigation Security Agency, Inc.

v. Daquera

G.R. No. 147473 March 30, 2004

Facts: On February 15, 1990, Pablo

Daquera was employed as a security guard

by ACD Investigation Security Agency, Inc.

Subsequently, or on September 1, 1994, he

was reassigned to Public Estates Authority

as a security ofcer. However, he was

illegally dismissed for dishonesty, without

prior written notice and investigation.

Daquera fled a complaint for illegal

dismissal, illegal suspension, illegal

deduction and non-payment of benefts

with the Labor Arbiter.

The Labor Arbiter fnds that the

respondents dismissal from employment is

illegal.

On appeal, the national Labor

Relations Commission [NLRC] afrmed the

Arbiters Decision. A motion for

reconsideration was also denied by the

NLRC.

Petitioner then fled with the Court

of Appeals a petition for certiorari seeking

to set aside the NLRC decision and

resolution. The CA afrmed the Decision of

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

14

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

the NLRC. A motion for reconsideration was

also denied by the Appellate Court.

Thus, this petition

Issue: Whether or not the respondents

dismissal from his work is valid.

Held: No, it is not.In order to constitute a

valid dismissal, two requisites must concur:

[a] the dismissal must for any of the causes

expressed in Article 282 of the Labor Code;

and [b] the employee must be accorded due

process, basic of which is the opportunity

to be heard and to defend himself.

Records show that respondent was

never notifed in writing of the particular

acts constituting the charge of dishonesty.

Neither was he required to give his side

regarding the alleged serious misconduct

imputed against him. Simply states,

respondent was not served by petitioner

with notices, verbal or written, informing

him of the particular acts for which his

dismissal is sought.

COCA-COLA BOTTLERS PHILIPPINES,

INC. vs. DOMINIC E. VITAL

G.R. No. 154384. September 13, 2004

Facts: Dominic E. Vital, respondent, was

employed by Coca-Cola Bottlers Philippines,

Inc., petitioner, as route driver/helper at its

Antipolo Plant, with a monthly salary of

P12,860.00. He was also assigned to

perform the duties of a salesman.

Petitioner, intending to increase the sale of

its products, implemented Operation

Rurok, a local marketing campaign that

allows its trusted wholesaler outlets to

retrieve foreign empties and/or bottles of

petitioners competitors, such as Pepsi Cola

and Cosmos, from regular customer outlets,

in exchange for Coca-Cola containers and

products.

Lagula, the District Sales

Supervisor, issued respondent

Miscellaneous Slip authorizing him to

deliver, in exchange for retrieved Pepsi-Cola

and Cosmos empties or bottles, 57 cases of

12 oz. Coca-Cola products to AMC Viray

Store situated in Tambunting Street,

Blumentritt. Subsequently Lagula again

handed respondent Miscellaneous Slip No.

75711 authorizing him to deliver, pursuant

to an exclusivity agreement, 90 cases of

12 oz. Coca-Cola products to Coras Store

situated in Cuenco Street. For the third

time, Lagula issued respondent

Miscellaneous Slip No. 87449 authorizing

him to deliver, as replacement for retrieved

foreign empties, 95 cases of 12 oz. Coca-

Cola products to John Uy at La Loma,

Quezon City.

Petitioner sent respondent a notice of an

investigation of its complaint against him

for forgery, fctitious sales transactions,

falsifcation of company documents,

unauthorized retrieval of empties, pursuant

to Sections 10 and 12, Rule 005-85 of the

companys Code of Disciplinary Rules and

Regulations. Petitioner then placed

respondent under preventive suspension. In

the meantime, petitioner, in an Interofce

Memorandum dated October 14, 1996,

stopped implementing Operation

Rurok.During the clarifcatory hearing

conducted by petitioner respondent

admitted that he deviated from the

instructions stated in the Miscellaneous

Slips handed to him by his supervisor,

Lagula. He stated that in three separate

instances, Lagula instructed him to deliver

the Coca-Cola products to other outlets.

Eventually, petitioner sent respondent an

Interofce Memorandum dated February 8,

1997 terminating his services for loss of

trust and confdence. Respondent fled with

the Labor Arbiter a complaint for illegal

dismissal and damages against.

Issue: Whether or not respondent is

entitled to reinstatement without loss of

seniority rights.

Ruling: Respondent who was illegally

dismissed from work is entitled to

reinstatement without loss of seniority

rights, full backwages, inclusive of

allowances, and other benefts or their

monetary equivalent computed from the

time his compensation was withheld from

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

15

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

him up to the time of his actual

reinstatement. In fact, there is no showing

that respondents acts were inimical to

petitioners interest. Petitioner has not also

shown that previously, respondent violated

any of its rules or regulations. Certainly,

respondents acts may be considered as

isolated incidents not amounting to a willful

disobedience or violation of petitioner

companys rules and regulations.

However, the circumstances obtaining in

this case do not warrant the reinstatement

of respondent. Antagonism caused a severe

strain in the relationship between him and

petitioner company. A more equitable

disposition would be an award of separation

pay equivalent to at least one month pay, or

one month pay for every year of service,

whichever is higher, (with a fraction of at

least six (6) months being considered as

one (1) whole year), in addition to his full

backwages, allowances and other benefts.

R.P. Dinglasan Construction, Inc. vs.

Atienza

G.R. No. 156104

June 29, 2004

Facts The petitioner R. P. Dinglasan

Construction, Inc. is a provider of a

Janitorial Services to Pilipinas Shell

Refnery Corporation. The respondents in

this case served as petitioners janitor

assigned with the Shell Corporation.

In a meeting, the petitioner informed

the respondent and three (3) other

employees that they will be terminated

because they lost in the bidding with Shell.

However they were informed that they may

re apply as helpers and redeployed in other

companies where petitioner has a

subsisting contracts.

Respondents however refused to

accept such ofer, contending that the ofer

is tantamount to demotion and they would

lost seniority status and would not be

guaranteed to work at a regular hours.

Later, a complaint was fled for non-

payment of their salary. During the

conciliation proceedings, petitioner

informed them that they will be reinstated

with Shell provided they have to submit

some documentary requirements. However,

they failed to do so, hence they will declared

absent without ofcial leave.

Labor Arbiter rendered decision in

the labor case, fnding that the respondent

were illegally dismissed and ordering their

restatement.

Issue: Whether or not the onus probandi

rest on the employer in an illegal dismissal

case.

Ruling: The Supreme Court held that, in

an illegal dismissal case, the unos probandi

rests on the employer to prove that its

dismissal of an employee is for a valid

cause. In the case at bar, petitioner failed

to discharge its burden. It failed to

establish that private respondents

deliberately and unjustifably refused to

resume their employment without any

intention of returning to work.

ELECTRUCK ASIA, INC. vs. EMMANUEL

M. MERIS ,et al.

Facts: Respondents and their twenty-

eight co-employees fled on February 1,

1996 a complaint for illegal dismissal with

prayer for reinstatement to their former

positions, with full backwages and without

loss of seniority rights.

By Decision of September 27, 1996

which noted that there was no need for

trial on the merits, Labor Arbiter De Asis,

fnding as follows: Here, complainants

concerted action demonstrates a moral

perverse attitude toward their employer. By

leaving their work unattended and undone

and sleeping on companys time, in efect,

complainants are robbing the company of a

fair days labor. This is plain and simple

dishonesty, and applying the Wenphil

doctrine which, by his words, upheld the

validity of the dismissal despite the non-

observance of due process of law,

dismissed respondents Complaint.

2006 BAR OPERATIONS

Faculty Chair: Atty Hilario Magsino

Over-all Chair: Nerissa Guirao

Academic Committee ead: Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Su!"ect ead: Madonna Dimaano

Academic Committee #em!er$: Lisa Tubilleja, Nerissa Guirao Ci!il" C#risto$#er %onoan &oli"

Ant#ony Mali'dem Ta(" Celso J. Hernandez Jr. Crim, Commer'ial" )ey )abago, Donnalee

*ilanga)emedial"

16

ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW ADAMSON COLLEGE OF LAW

CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW CASE DIGESTS IN LABOR LAW

2006 BAR OPERATIONS 2006 BAR OPERATIONS

The Labor Arbiters decision was

appealed to the National Labor Relations

Commission and by Resolution of May 28,

1997, the NLRC dismissed the appeal for

lack of merit. Respondents fled a petition

for certiorari before the Court of Appeals .

By Decision 31, 2000, the Court of Appeals

(CA) reversed and set aside the Resolutions

of the NLRC . In reversing the NLRC, the

appellate court held that both the NLRC

and the Labor Arbiter failed to anchor their

conclusions upon substantial evidence. At

the outset, it should be stressed that the

petitioners are not required to prove their

innocence of the charges leveled against

them by their employer. A su converso, the

employer must afrmatively show rationally

adequate evidence that the dismissal was

for a just cause.

ISSUE: Whether or not there exist a just

cause for terminating respondents

employment

RULING: It is settled that the fndings of

facts of administrative agencies, such as

the NLRC, must be respected so long as

they are supported by substantial

evidence. Deviation from this well-

established rule must, however, be made

when the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC

clearly misappreciated the facts, thereby

impairing the employees right to

security of tenure.

In illegal dismissal cases, the onus

probandi lies on the employer. Petitioner

has failed in this respect, however.Contrary

to petitioners allegation and the fndings of

both the Labor Arbiter and the NLRC, no

evidence was presented to prove that

respondents were caught sleeping by

Datson. Why no sworn statement or

afdavit of Datson to substantiate such

claim, petitioner profered no reason.

Parenthetically, it is highly unlikely and

contrary to human experience that all ffty-

fve employees including respondents were

at the same time sleeping. As for

petitioners contention that the Serrano

ruling is not applicable, the same is well-

taken but not for the reason it profered.

The Serrano doctrine which dispenses with

the twin requirement of notice and hearing

does not apply to the case at bar because,

as already discussed, petitioner had not

proved that the termination of respondents

was for a just or authorized cause.

CHIANG KAI SHEK COLLEGE, ET AL. VS.

COURT OF APPEALS

G.R. No. 153988, August 24, 2004

Facts: Belo is a teacher of CKSC since

1977. She applied for a leave of absence for

SY 1992-1993 because her children had no

yaya to take care of them. Her leave of

absence was approved. After one-year leave

of absence, she was denied and not

accepted when she signifed her readiness

to teach. Belo fled with the Labor

Arbitration Ofce a complaint for illegal

dismissal. The Labor Arbitrator dismissed

the complaint, reasoning that there was

simply no available teaching load for her.

On appeal, NLRC reversed the decision of

the Labor Arbiter. Petitioner fled a petition

for certiorari with the CA. CA ruled that

NLRC acted correctly when it ascertained

that Belo was dismissed constructively.

Thus, this petition

Issue: Whether or not Belo was illegally

dismissed.

Held: Yes, It must be noted that Belo has

been a full-time teacher in CKSC for 15

years until she took a leave of absence for

the SY 1992-1993.Under the Manual of

Regulations for Private Schools, for a

private school teacher to acquire a

permanent status of employment, the

following requisites must concur: 1) The

teacher is a full-time teacher; 2) the teacher

must have rendered 3 consecutive years of