Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Decision and Direction of Election

Uploaded by

Michael Phillips0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

491 views38 pagesA ruling from the National Labor Relations Board on a representation petition filed by the Transport Workers Union Local 100, on behalf of workers at NYC Bikeshare.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA ruling from the National Labor Relations Board on a representation petition filed by the Transport Workers Union Local 100, on behalf of workers at NYC Bikeshare.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

491 views38 pagesDecision and Direction of Election

Uploaded by

Michael PhillipsA ruling from the National Labor Relations Board on a representation petition filed by the Transport Workers Union Local 100, on behalf of workers at NYC Bikeshare.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 38

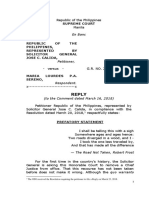

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BEFORE THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD

REGION 2

NYC BIKE SHARE LLC

Employer

and Case No. 02-RC-131200

TRANSPORT WORKERS UNION LOCAL 100

affiliated with TRANSPORT WORKERS UNION

OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO

Petitioner

DECISION AND DIRECTION OF ELECTION

NYC Bike Share LLC (the Employer) is engaged in the short-term rental of bicycles and

the operation of a bike-share program. Transport Workers Union Local 100, affiliated with

Transport Workers Union of America, AFL-CIO (the Petitioner) filed a representation petition

under Section 9(c) of the National Labor Relations Act seeking to represent a unit of all full-time

and all regular part-time employees at three of the Employer's facilities, two of which are located

in Manhattan and one in Brooklyn, New York, excluding all other employees, including

employees in the Marketing, Finance, and Human Resources departments, guards, professional

employees, and supervisors as defined by the Act.'

Upon a petition filed under Section 9(b) of the National Labor Relations Act (the Act), as

amended, a hearing was held before a hearing officer of the National Labor Relations Board (the

Board).

Pursuant to the provisions of Section 3(b) of the National Labor Relations Act, the Board

has delegated its authority in this proceeding to the Regional Director, Region 2.

Based upon the entire record in this matter2 and in accordance with the discussion above,

I conclude and find as follows:

1. The Hearing Officer's rulings are free from prejudicial error and hereby are affirmed.

At the hearing, the Petitioner amended its petition to exclude employees in the Marketing, Finance, and Human

Resources Departments.

2 The briefs filed by the parties have been duly considered. The Petitioner's citation corrections are hereby admitted,

inasmuch as they do not substantively alter its brief.

2. The parties stipulated, and I find, that the Employer is a limited liability corporation

organized under the laws of the State of New York engaged in the short-term rental of bicycles

and the operation of a bike-share program, with facilities located at 5202 3rd Avenue, Brooklyn,

New York3 (the Sunset Park facility), 8th Avenue and 31St Street, New York, New York (the

Farley Building), and Delancey Street near Bialystoker Street, New York, New York (the

Delancey Street facility). Annually, the Employer, in the course and conduct of its business

operations, derives gross revenues in excess of $500,000, and purchases and receives at its

Manhattan and Brooklyn facilities, goods and services in excess of $5,000, directly from points

outside the State of New York.

Accordingly, I find that the Employer is engaged in commerce within the meaning of

Sections 2(6) and (7) of the Act, and it will effectuate the purposes of the Act to assert

jurisdiction herein.

3. The parties stipulated, and I find, that the Petitioner is a labor organization within the

meaning of Section 2(5) of the Act.

4. A question affecting commerce exists concerning the representation of certain employees

of the Employer within the meaning of Section 9(c)(1) and Section 2(6) and (7) of the Act.

The Petitioner seeks to represent all full-time and all regular part-time employees,

including seasonal employees, of the Employer, at its Sunset Park facility, its Farley Building

facility, and its Delancey Street facility, excluding all other employees, including employees in

the Marketing, Finance, and Human Resources departments, guards, professional employees, and

supervisors as defined by the Act. In that regard, the Petitioner asserts that the seasonal

employees share a community of interest with permanent employees. The Petitioner further

contends that the seasonal employees have a reasonable expectation of future reemployment.

Finally, the Petitioner submits that the Employer has failed to carry its burden of proving that the

disputed supervisors have the requisite authority under Section 2(11) of the Act, and are eligible

to vote.

The Employer contends that the petitioned-for unit is inappropriate because the seasonal

employees do not share a community of interest with the Employer's permanent employees and

do not have a reasonable expectation of future reemployment with the Employer. The Employer

also contends that certain individuals should be excluded from the unit because they are

supervisors within the meaning of Section 2(11) of the Act. These individuals are: Bike

Mechanic Supervisors Briton Malcolmson, Humberto Facey, William Gaerre, Indio Galarza, and

Carlos Rivera, Bike Checker Supervisor Kelly McGowan, Warehouse Supervisor Jesse Taylor,

3 Consistent with the Petition and the Employer's exhibits, it appears that the reference in the record to 3203 3'

Ave., Brooklyn, NY, is a transcription error.

2

Vehicle Supervisors Aldrick Bramwell, Dyrell Epps, and Carl Johnson, Dispatch Supervisors

Chris Gittens and Jacob Boersma4 , Station Tech Supervisors Angel Bianchi and Murat Coskun,

and Call Center Supervisors Jermaine Clarke, Tiandra Razor, and Selena Brewster. The

Employer relies on the following indicia in support of its position: authority to hire and

discipline; authority to effectively recommend hire, discharge and promotion; and, authority to

assign and responsibly direct. The Employer also relies on secondary indicia, such as differences

in compensation, attendance at meetings designated as "management-only," scheduling and

approving of paid time off, and access to inventory.

I have considered the evidence and the arguments presented by the parties. As discussed

below, I find that the petitioned-for unit is an appropriate unit, because seasonal employees share

a community of interest with permanent employees of the Employer and because they have a

reasonable expectation of future reemployment. Further, I find that the Employer has failed to

carry its burden of proving that the following alleged supervisors possess the requisite

supervisory indicia. Those individuals are Bike Mechanic Supervisors Briton Malcolmson,

Humberto Facey, William Gaerre, Indio Galarza, and Carlos Rivera, Warehouse Supervisor

Jesse Taylor, Vehicle Supervisors Aldrick Bramwell, Dyrell Epps, and Carl Johnson, Dispatch

Supervisor Chris Gittens, Station Tech Supervisors Angel Bianchi and Murat Coskun, and Call

Center Supervisors Jermaine Clarke, Tiandra Razor, and Selena Brewster. Accordingly, those

named employees are eligible to vote. I find that Bike Checker Supervisor Kelly McGowan and

Dispatch Supervisor Jacob Boersma are supervisors within the meaning of Section 2(11) of the

Act and therefore, are ineligible to vote.

I. FACTS

A. BACKGROUND

The Employer operates a bicycle sharing system in New York City. This system allows

annual subscribers and members of the general public to rent bicycles for short-term use. Users

may select and return bicycles at any one of 332 docking stations located throughout the city.

With approximately 6,000 bicycles available for use, the Employer's bicycle sharing system is

the largest in North America. Currently, the Employer employs 24 9 employees, approximately

96 of which are classified as seasonal. Accordingly, the seasonal employees comprise about 30%

of the petitioned-for unit.

Michael Pellegrino serves as the Employer's Director of Operations.5 The five managers

who report directly to Pellegrino are Bicycle Fleet Department Operations Manager Phil

4 At the hearing, the parties stipulated that the status of Dispatch Supervisor Alex Marks is no longer in dispute and

he is hereby excluded from the unit as a supervisor within the meaning of Section 2(11) of the Act.

5 The record does not reveal to whom Pellegrino reports and no further evidence was adduced regarding the

Employer's overall managerial structure.

3

Capezio, Bicycle Redistribution Operations Manager Christopher Lewis, Technical Service

Operations Manager Tyler Justin, and Call Center managers Tina Arniotis and Vera Thompson.

The Bicycle Fleet Department is rgsponsible for the maintenance and repair of the bikes.

The bicycle mechanics work in the Sunset Park facility and the Farley Building. They are

assisted by warehousemen who load and unload bikes for repair and distribution back into the

system. The mechanics' work is complimented by the bike checkers, who work in the field, and

perform light maintenance on bikes.

The Bicycle Redistribution Department is charged with moving and reallocating bicycles

throughout the Employer's citywide system in order to meet usage patterns. This department is

comprised of two divisions. These are fleet/field employees, who are responsible for the

physical transportation of bicycles and dispatch employees, who coordinate the movements of

the field employees. The record indicates that the fleet/field employees work out of the

Delancey Street facility, while the dispatch employees work in the Sunset Park facility.

The Station Technician Department is responsible for maintaining the 332 docking

stations that are located throughout the bike-sharing system. Specifically, the station technicians

ensure the functionality of the payment kiosks and the bicycle docks. The record is unclear

regarding the facility that the technicians report to before starting their field work, but it appears

that the department's operations manager works out of the Sunset Park facility.

The Call Center handles customer service inquiries by phone and email. To assist with

customer service, the Employer also utilizes field employees that it classifies as ambassadors.6

The record does not indicate the exact location of the Call Center.

B. SUPERVISORY STATUS OF CONTESTED INDIVIDUALS

Bicycle Fleet Department

Bicycle Fleet Department Operations Manager Phil Capezio is responsible for the work

of the bike mechanics, bike checkers, and the warehouse employees. Capezio, who is directly

responsible for the department, did not testify regarding the duties and authority of the bike

mechanic supervisors.

Bike Mechanic Supervisors

Lead Supervisor Timur Mukhodinov reports directly to Phil Capezio. In addition to

Mukhodinov, four bike mechanic supervisors, Humberto Facey, Indio Galarza, Will Gaerre and

6

The record is unclear as to the precise departmental classification of the ambassadors.

4

Carlos Rivera, work at the Sunset Park facility with approximately eighteen mechanics. The

fifth bike mechanic supervisor, Briton Malcolmson, works at the Farley Building with

approximately twelve mechanics. The record reveals that bike mechanic supervisors earn $18

per hour, while bike mechanics earn $16.50 per hour.

Director of Operations Michael Pellegrino testified in a general manner about the work

responsibilities of the bike mechanic supervisors. He affirmed the accuracy of the bike mechanic

supervisor job description, but he conceded that he could only generally describe the work of

supervisors. He could not, for example, "tell you what they all did yesterday" or "last month."

The job description states that the "Key Aspects" of the bike mechanic supervisor

position are as follows:

Follow safe work practices and help to create a safe working environment

Ensure all maintenance/repairs are completed to NYCBS [New York City Bike

Share] standards

Maintain and uphold all NYCBS and Bike Shop policies and procedures; reward

or discipline direct reports as necessary

Train and supervise Bike Mechanic staff

Supervise the daily workload of Bike Mechanics and monitor production rates to

ensure compliance

Manage the schedule of Bike Mechanics to ensure full coverage of all shifts

Create End of Shift reports and Productivity Reports

Accurately manage parts consumption and inventory levels

Conduct periodic staff evaluations and provide feedback

Work with Dispatch, Vehicle Fleet, Station Technicians, and other NYCBS staff

on cross training and interdepartmental cooperation

Perform all other, additional duties as assigned.

Regarding the work duties of supervisors, Pellegrino testified that, on average,

supervisors spend less than 50% of their working time performing bicycle repairs. When not

performing repairs, Pellegrino stated that supervisors inspect the mechanics' work in accordance

with the Employer's repair standards. No evidence was adduced, however, regarding these

standards and the consequences of failing satisfy them.

Pellegrino asserted that supervisors have the authority to discipline the bike mechanics.

He testified that "very recently" a bike mechanic supervisor engaged in a "disciplinary

conversation" with an employee. Pellegrino did not provide the identity of the individuals

involved, the date of the conversation, or the subject of the conversation, and the Employer did

not offer any documents into evidence concerning this disciplinary conversation.

5

Further, Pellegrino maintained that the bike mechanic supervisors are responsible for

drafting written employee performance evaluations. Specifically, he testified that during the

most recent round of seasonal hiring, the supervisors observed the new mechanics over the

course of their initial two-week training. The supervisors made a recommendation to Capezio as

to whether they required additional training. The Employer did not offer any evaluations into the

record, or adduce any further testimony regarding whether the training program continued or the

impact on the mechanic's employment. With respect to permanent staff, Pellegrino claimed that

in about January 2014, bike mechanic supervisors provided "substantive input" to annual

evaluations. He was unable to state whether the "substantive input" was oral or written. As with

the performance evaluations for seasonal hires, Pellegrino failed to provide specific information

regarding the use of the evaluations, and the Employer failed to offer any of these performance

evaluations into evidence.

Finally, Pellegrino noted that supervisors alone have access to the inventory closet and

are responsible for checking the inventory in and out of the closet. Although Pellegrino claimed

that the inventory was valuable, no further details were adduced regarding the implied

importance of such access.

Although Pellegrino has knowledge of the Employer's policies and procedures, he

admitted that he is not involved in the day-to-day operations of the shop. As a result, his

testimony regarding the daily work of the bike mechanic supervisor was very conclusory and

without any specifics. The absence of documentary evidence supporting his assertion that the

supervisors responsibly direct and evaluate employees undercuts his testimony in that regard.

With respect to disciplinary authority, Pellegrino references a single verbal counseling. Again,

no documentary evidence was presented to show that the supervisors have authority to issue

written warnings or the discretion to independently discipline employees.

Lead Supervisor Timur Mukhodinov works at the Sunset Park facility and reports directly

to Operations Manager Phil Capezio. Mukhodinov testified that the bike mechanic supervisors

primary responsibilities include disciplining and rewarding mechanics, tracking time and

attendance, inventory, and general production.

Concerning the authority to discipline, Mukhodinov testified that bike mechanic

supervisors have the authority to give verbal warnings or send mechanics home due to

attendance. He provided hearsay testimony that he heard Capezio tell Facey, Rivera, and

Galarza that they could send individuals home for "[r]epeated poor attendance, severely poor

attendance, potential physical altercation or a need for investigation pertaining to their

performance or their honesty on their reporting of the bikes they repair." Ultimately,

Mukhodinov conceded that, in practice, the supervisors never issue discipline without first

speaking with him and Capezio. Mukhodinov added that, since he became lead supervisor, no

bike mechanic had ever been sent home for disciplinary reasons. I note that Mukhodinov failed

6

to provide any examples of supervisors disciplining mechanics and the record is silent as to the

effect of a verbal warning on the terms and conditions of employment of the recipient.

Regarding the authority to reward employees, the evidence appears to be even weaker.

Although Mukhodinov testified that supervisors can give "shout-outs," which is a type of verbal

performance recognition that enters the recognized employee into a departmental raffle, the

record indicates that the supervisors share this ability with all individuals in the department,

including the bike mechanics, and that supervisors have no role in approving the giving of

"shout-outs."

With respect to assignment and responsible direction, Mukhodinov noted that the

supervisors can assign, in that they determine the order and type of repairs to be completed in a

given time period. Mukhodinov testified that bike mechanics are required to follow directions or

instructions received from the supervisors. He claimed that the supervisors are responsible for

special projects. As an example, Mukhodinov stated that the supervisors can set up production

lines to take useable parts off of broken bikes. In selecting individuals for special projects,

Mukhodinov offered the hypothetical example of a supervisor assigning the repairing of rear

hubs to an individual considered "more knowledgeable about that particular component on the

bicycle."

Mukhodinov admitted that supervisors can spend up to 50% of their time working

alongside the mechanics repairing bicycles. Although the Employer's May 2014 Bicycle Fleet

Production Report and First Quarter Bicycle Fleet Report indicate that the supervisors spent an

average of 30 percent of their working hours repairing bicycles, with individual percentages

ranging from 19 to 38 percent, Mukhodinov noted that these percentages, which are self-

reported, vary from month to month.

Mukhodinov did not state, with any degree of specificity, what the supervisors do when

they are not repairing bicycles. In a general manner, he testified that supervisors are responsible

for maintaining and upholding the Employer's policies and procedures and ensuring that time

and attendance is satisfactory. He also testified that the disputed supervisors are involved in the

creation of daily or weekly reports addressing performance and attendance. He stated that the

reports also relay general questions posed by the mechanics and supervisors and provide an

assessment of morale in the shop. I note, however, that the Employer failed to offer into

evidence any examples of these policies and procedures, the daily and weekly reports,, or

employees with performance deficiencies or serious time-and-attendance issues.

With regard to time and attendance, Mukhodinov noted that supervisors play a role in

scheduling the mechanics. Mukhodinov stated that supervisors "take the availability" of the

mechanics once a month and notify Mukhodinov and Bicycle Fleet Operations Manager Capezio

7

"of any changes in the bike mechanics' weekly or daily schedules." Mukhodinov testified that

bike mechanic supervisors can approve paid time off for mechanics without consulting with him,

although he noted that the supervisors will typically speak with him or Operations Manager

Capezio before granting any such approval.

Mukhodinov estimated that either he or Capezio will meet with the bike mechanic

supervisor at the Farley Building, Briton Malcolmson, every few weeks, and with the four bike

mechanic supervisors at the Sunset Park facility weekly. According to Mukhodinov, at these

meetings they discussed production, behavior, morale, rewards, and inventory needs.

Finally, Mukhodinov testified that bike mechanic supervisors participated in meetings

designated as management-only at which human resources and union issues were discussed.7

Mukhodinov's testimony is based on his first-hand knowledge of the daily activities of

the bike mechanic supervisors. He clearly limited the supervisor's disciplinary authority to

verbal counseling regarding work performance issues, not misconduct. Overall, his testimony

demonstrates that the alleged supervisors act as a liaison between the mechanics and the

departmental manager, and do not possess independent authority to discipline or reward

employees. Similarly, his explanation of work assignments indicates that the supervisors do not

exercise discretion. Rather, the work is routine and matched to an employee's skill set. Most

importantly, with respect to supervisors' time spent performing unit work, Mukhodinov

explained that the proffered production reports are an incomplete sample of the time that

supervisors actually spend performing repair work alongside the mechanics.

Briton Malcomson, the only bike mechanic supervisor to testify, emphasized that his

work duties at the Farley Building are "similar to every other mechanic in the shop." He testified

that he had a work station like all of the other mechanics, and he estimated that he spent, on

average, 50 to 7 5 percent of his day performing repair work. Although this number is

significantly higher than the 19 percent recorded for May 2014 in the Bicycle Fleet Production

Report entered into evidence by the Employer, Malcolmson explained that "[t]here is a lot of

work that is not entered into NetSuite, which is the computer system [used in part to calculate the

amount of repair work performed]... So, for instance, I spent time where it's like I'm at my

workbench for 7 5 percent of the day rebuilding hubs or pulling broken parts out and like

replacing them with new parts. That doesn't get put into NetSuite." Malcolmson further

explained that the estimated 43 percent of time spent performing repair work in the first quarter

of 2014, also entered into evidence by the Employer, undercounted his actual time spent doing

such work, as a lot of the repairs weren't being tracked in any way.

7 Human Resources Manager Pean similarly testified that all supervisors attended management-specific trainings

regarding the unionization campaign and workplace non-discrimination policies.

8

Malcolmson vigorously denied having the supervisory authority to discipline, stating that

he was never told that he could issue verbal or written warnings or send employees home for

disciplinary infractions, and adding that he has never done so. Instead, Malcolmson characterized

his work as bike mechanic supervisor as essentially a middleman between the mechanics and

Capezio and Mukhodinov. He stated that he viewed his job as "relaying what Timor

[Mukhodinov] and Phil [Capezio] set out as the requirements and the results" of the production

reports to the mechanics. Malcolmson testified, for example, that if Mukhodinov and Capezio

"tell me that someone is below or above a [production] metric, I relay that to the employee" and

assist the mechanics in improving his or her performance. He further stated that he has no power

to set the schedules of the mechanics. He also denied having the ability to assign work tasks

within the facility.

Although Malcolmson admitted to participating in employee evaluations in January 2014,

and to authoring the evaluations of three employees, the record is silent as to how these

evaluations affected the terms and conditions of employment of the bike mechanics.

Additionally, I note that the Employer did not enter any employee evaluations into evidence.

Finally, although Malcolmson admitted that he recommended an employee for a

promotion, he clarified that he did so in response to an open solicitation issued to all bike

mechanics at the Farley Building. The record testimony indicates that the Employer did not act

on this recommendation. The record contains no evidence concerning the number of such

promotional recommendations received and the identities of those who made the

recommendations.8

Warehouse Supervisor

In addition to the repair work performed by Malcolmson and the bike mechanics, the

Farley Building also operates as the Employer's warehouse. One of the three warehousemen,

Jesse Taylor, is alleged to be statutory supervisor.

The evidence offered by the Employer in support of Taylor's ineligibility and exclusion

from the unit is scant.9 Director of Operations Pellegrino testified that Taylor "helps with the

loading and unloading [at the Farley Building], and the general upkeep of that facility." The

record further indicates that Taylor works alongside his two coworkers in the warehouse.

Finally, although she did not mention Taylor by name or position, Human Resources 'Manager

8 I note that the Employer alleges that Malcolmson participated in several new employee interviews, a point

conceded by Malcolmson. However, the evidence indicates that Malcolmson did so while serving as bike checker

supervisor, and not in his current position as bike mechanic supervisor. The record does not contain any evidence

indicating that Malcolmson has continued to participate in new employee interviews since becoming bike mechanic

supervisor in approximately October 2013.

9 I note that the Employer's brief does not address the supervisory status of Taylor.

9

Pean testified that all supervisors were required to attend two management-specific training

sessions: the first addressing sexual harassment and related workplace antidiscrimination laws,

and the second involving the unionization effort. The Employer did not provide any additional

testimonial or documentary evidence concerning the supervisory authority of disputed supervisor

Taylor.

Bike Checker Supervisors

For general maintenance of its bike fleet, the Employer dispatches bike checkers to the

field, rather than transporting the bikes to the shop. The bike checkers inspect the bikes and

perform light repairs in the field. Kelly -McGowan is the supervisor of approximately twelve

bike checkers, all of whom are seasonal employees.

As with Mukhodinov, McGowan reports directly to Operations Manager Capezio. The

evidence concerning McGowan's duties was presented through the testimony of Bicycle

Redistribution Operations Manager Christopher Lewis because he served as McGowan's direct

supervisor for a short period of time.1 Notably, Lewis stated several times during his testimony

that he could not provide accurate, current information concerning the present duties of

McGowan, and identified Capezio as the individual best able to provide that information.

Nonetheless, Lewis testified that McGowan hired all of the bike checkers working in the

2014 season. In recounting the hiring process, Lewis stated that McGowan conducted all of the

job interviews himself, with the exception of one interview which Lewis also attended. He

testified unequivocally that McGowan made all of the hiring decisions on his own, stating, for

example: that McGowan was "pretty autonomous in the process and they were his decisions";

that McGowan "didn't collaborate with anyone else" in deciding which bike checkers to hire;

and that McGowan "was the sole person... who had that decision [to hire bike checkers.]"

Lewis also claimed that McGowan has the authority to issue verbal and written warnings,

but he did not provide any specific examples of him having done so. He noted only that

McGowan has discussions with bike checkers regarding their production. Because he is no

longer McGowan's direct supervisor, Lewis emphasized that he could not "provide an answer

that's as detailed as you want" regarding specific instances of McGowan participating in

conversations with checkers concerning their production. In that regard, Capezio generates

production reports which indicate each bike checker's undocking, maintenance, inspection, and

redocking of bikes. The Employer can monitor the field work by tracking the hourly, daily, and

weekly production rates. The Employer failed to offer evidence of any record or personnel file

note of McGowan's conversations with bike checkers regarding their performance. The

10

As noted previously, Capezio did not testify regarding the alleged supervisors within his department.

10

Employer also failed to enter into evidence any examples of verbal or written warnings issued by

McGowan.

Lewis also testified that McGowan is solely responsible for scheduling. He admitted,

however, that McGowan's discretion in scheduling is limited, as employees work Monday

through Friday on "set schedules" of 7 am to 3 pm and 2 pm to 10 pm. He noted that McGowan

frequently interacts with Dispatch Supervisor Alex Marks to determine the times in which the

trailers and checkers will be working in the field.

Bicycle Redistribution Department

Turning to the field work carried out by his own department, Operations Manager

Christopher Lewis described the job duties of the six disputed redistribution department

supervisors. Although this department has two divisions, Field/Fleet and Dispatch, Lewis

testified that the supervisors in both divisions share certain responsibilities.

Lewis claimed that all of the redistribution supervisors have the authority to issue verbal

and written warnings. He admitted that the authority to issue written warnings was not given to

the fleet/field supervisors until the week before the hearing. He noted that the supervisors can

choose between issuing a verbal or written warning, or sending an employee home if the

employee arrives more than fifteen minutes late. Again, the Employer failed to offer into

evidence any documents memorializing verbal or written warnings issued by a supervisor. As

discussed more fully below, stipulated dispatch supervisor Alex Marks denied having any

authority to issue written warnings. In this regard, I note the testimony by Director of Operations

Pellegrino, who similarly stated, "rilf a disciplinary issue bubbles up to the level of a written

warning or a performance improvement plan, often I'll be involved at that point."

Lewis stated that all supervisors are held accountable for the performance of their

employees, testifying, "they're responsible for reporting [employees' performance data], they're

responsible with talking with the employees about it, and they're responsible for escalating it to

the next step," and for ensuring that employees are in compliance with the Employer's standard

operating procedures. Again, the production reports documenting the performance of each

employee are not in evidence. Similarly, the Employer failed to offer into evidence any of the

standard operating procedures the supervisors are charged with enforcing.

Finally, Lewis noted that all of the supervisors attend management-only meetings, with

the fleet/field supervisors meeting with him weekly and the dispatch supervisors more

frequently.

11

The Field/Fleet Division

The fleet/field division is responsible for physically moving bicycles and docking stations

around the system. There are approximately 56 employees in the division, classified either as

drivers or balancers. The record indicates that disputed fleet/field supervisors, Aldrick

Bramwell, Dyrell Epps, and Carl Johnson, earn $19 per hour, while drivers earn $18 per hour

and balancers $14.50 per hour.

Lewis testified that the core responsibility of the fleet/field supervisors, who work out of

the Delancey Street facility, is "being the face supervisors in the field." Elaborating, Lewis

stated that the supervisors, for example, ensure that the drivers and rebalancers arrive for work

on time with the proper safety gear, conduct pre- and post-trip inspections on vehicles, and report

maintenance problems. During their post-trip inspections, the supervisors frequently inform

drivers that they cannot clock out until, for example, they return to the truck to clean up garbage

left in the vehicle.

The record reflects that the supervisors accompany new employees on what the

Employer terms "ride-alongs." These are shifts in which new employees are joined by at least

one supervisor to evaluate the new employees' performance. While the record is unclear, it

appears that these ride-alongs occur for drivers only, and not balancers. Lewis testified that each

employee will have a total of three full-shift ride-alongs in the first three weeks of employment.

On at least two of the ride-alongs, the new employee will be accompanied by a supervisor.

Lewis stated that, after the three weeks, the supervisors will make a recommendation regarding

the abilities of the new employee, and may, for example, recommend that a new employee be

"give[n] more time before they're allowed out on their own," or may "conclude that the driver

shouldn't be driving trucks." Lewis testified that the recommendation of the supervisors is

followed. Lewis did not state if the recommendation is in written or oral form, and the Employer

did not enter any examples of such recommendations into evidence. He also noted that since

January 2014, when he became Operations Manager, the ride-alongs have not resulted in the

termination of any employee.

Lewis added that the supervisors will inform him if they are having a repeated problem

with an employee; he was, however, unable to highlight any specific instance of repeated

problems with an employee, although he noted, "I'm sure they're in my [e-mail] box." No

emails were proffered into evidence.

Finally, Lewis noted that, Aldrick Bramwell, the morning supervisor, is responsible for

deployment operations, which means moving docking stations around the system to

accommodate usage patterns. Lewis stated that Bramwell "will choose his eight or so

individuals" to work on a given deployment operation, but he also noted that he typically

12

chooses more seasoned employees. Further, Lewis testified that Bramwell "will request from

[dispatch supervisor] Jacob [Boersma] and myself as a curtesy [sic], so we're all in the loop,

which individuals will be assisting in the effort for that day..." Additionally, Lewis indicated

that he, in fact, may choose Bramwell's team, noting, "we'll select his staff, based on who is

scheduled to work, who he wants to work with him in the field."

The Dispatch Division

Approximately fourteen dispatchers track the locations of all the field employees. Lewis

testified that the dispatch supervisors, Alex Marks, Jacob Boersma, and Chris Gittens, are each

responsible for discreet operational aspects of the Bicycle Redistribution Department.

Marks is the "logistics coordinator."1 1 He works closely with Bike Checker Supervisor

Kelly McGowan to coordinate the work of dispatchers, valets, and bike checkers. Lewis testified

that Marks hired "pretty much" all of the valet attendants himself. The valets work at heavily-

used stations in the system in order to assist customers with the docking and with loading of

bicycles onto trucks for transport. Lewis stated that Marks determined who he wanted to

interview for the position and conducted all of the interviews himself, with the exception of "two

or three" which Lewis also attended. Lewis emphasized that Marks had "sole discretion on who

he want[ed] to hire," and described an incident in which Marks' overrode Lewis'

recommendation concerning the hiring of a certain individual.

Marks corroborated that he has authority to hire the valets. Marks also stated that he was

involved in the hiring of the seasonal, part-time dispatchers, describing it as "consensus driven

with Chris [Lewis] in terms of who we hired." Concerning the dispatchers, Marks stated that,

following their hire, he was responsible for their training and on-boarding schedule. Marks also

corroborated that he approves paid time off, has the authority to verbally "counsel a dispatcher,"

and can send an employee home for excessive tardiness, although he has never done so. During

his testimony, Marks also offered his belief that "formally [he is] held accountable" for the

performance of dispatchers.

Boersma is the "fleet coordinator." He is responsible for scheduling the 56 drivers and

balancers, fleet maintenance, and "keeping track of what the three field/fleet supervisors report

to him regarding on-time performance, preparedness and any personnel issues." Lewis testified

that Boersma hired all of the drivers in the Bicycle Fleet Department. This testimony is

unrebutted. Further, Boersma formally approves or denies paid time off for all drivers and

balancers and was involved in the Employer's efforts to lease additional trucks for its vehicle

fleet.

1 1 The parties stipulated that Marks is a supervisor within the meaning of Section 2(1 1 ).

1 3

Finally, Gittens is the overnight supervisor and is responsible for "quality control." In

this capacity, Gittens works with the Employer's database, NetSuite, to ensure that "work orders

are being done and the tasks... are being scheduled." As night supervisor, Gittens also "assist[s]

with overnight scheduling" and approves time off for night shift employees.

Lewis testified that approximately three weeks prior to the hearing, Gittens recommended

the termination of an employee suspected of stealing time. After receiving this recommendation,

Lewis conducted his own investigation and verified Gittens' suspicions that the employee was

stealing time. Lewis testified that, following the investigation, "his [Gittens'] write-up

[recommending termination] was forwarded to HR with my signature attached." As of the date

of the hearing, according to Lewis, the employee had not yet been terminated. Notably, the

Employer failed to enter the write-up referenced by Lewis, or any other documents concerning

the termination recommendation into evidence.

Additionally, both Gittens and Marks are charged with summer advertisements and map

placement. In this capacity, Lewis and Marks chose staff based on availability and skill level,

selecting "people that have been around since deployment so that they can troubleshoot and are

able to swap the maps for stations that are a little more finicky."

The record indicates that dispatch supervisors Marks, Boersma, and Gittens earn $18 per

hour, while the dispatchers, with the exception of one, earn $16.50 per hour.12

Station Technician Department

Operations Manager Tyler Justin reports directly to Pellegrino. His department is

responsible for maintenance of the docking stations. Supervisors Angel Bianchi and Murat

Coskun report directly to Justin and they oversee the work of about 2 7 technicians, who are

assigned to various locations in the field by the dispatchers.

Station technicians have three titles: associate, tier 1, and tier 2 technician, depending on

skill level. The associate station technicians focus primarily on power-related issues at the

docking stations. Tier I technicians focus on the stations' docking points. Tier 2 technicians

address issues arising inside the stations' payment kiosks, including problems related to modems

and data links.

According to Justin, the supervisors spend approximately 60% of their time performing

"supervisory work," and the remainder 40% of their time in the field. Discussing what he termed

"supervisory work," Justin testified that the primary task in which supervisors engage is

12 As part of an agreement between her and the Employer upon her transfer from the Washington, DC bike-share

system, the dispatcher who does not earn $16.50 per hour earns $18 per hour.

14

"management of the schedule." As an example, he stated that the supervisors help to ensure

adequate coverage for busy weekends and track down substitutes for employees who call out.

While Justin indicated that supervisors could edit work schedules on their own, it appears that

they in fact consult with him regarding all scheduling issues. Justin characterized his interaction

with the supervisors as "always sort of a constant discussion" concerning technician shift

assignments. He also noted that the supervisors do not have independent authority to grant extra

hours or assign additional employees for a shift.

Regarding assignment and responsible direction, Justin testified that the work

assignments of technicians are "sort of prescribed already, which technician should be headed to

which stations." He further noted that, in order to receive their daily assignments, the

technicians interact directly with the dispatchers in the Bicycle Redistribution Department.

Justin testified, though, that if there is an unusually large amount of repair work needed on a

certain system component, such as touch screens, the supervisors "help [him] determine" the

technicians who will be working on those repairs. 1-le explained that, in the event technicians are

temporarily reassigned from their typical repair work, the dispatchers will be informed and the

technicians will receive their assignments directly from the dispatchers.

Justin testified that the supervisors have the independent authority to issue verbal

disciplines. Justin, however, failed to identify any specific instance in which a supervisor so

issued verbal disciplinary action.

Finally, Justin testified that in January 2014, prior to his becoming operations manager,

the supervisors participated in evaluations for the station technicians. This is the last time station

technicians were evaluated. Justin stated that this evaluation considered such areas as time and

attendance, attitude, cleanliness, and neatness. Justin added that the evaluations contained a

section for corrective action. Justin testified that, as far as he was aware, the prior operations

manager and the supervisors spoke with the station technicians about how they could improve

their performance. Justin did not state whether the supervisors independently determined the

corrective action to be taken. Notably, the Employer failed to enter any of these performance

evaluations into evidence.

The Call Center

The Call Center is managed by Tina Arniotis and Vera Thompson. The three disputed

call center supervisors are Jermaine Clarke, Tiandra Razor, and Selena Brewster.

Pellegrino testified to the general accuracy of the call center supervisor job description,

even though he did not know when the job description was created or when he last viewed the

15

job description. I note that Pellegrino was unable to state the number of employees employed in

the Call Center.

The job description states that the primary responsibilities of the call center supervisors

are:

Supervise a team of call center staff Supervisory responsibilities include the

following:

Maintain staff schedules and timesheets.

Prepare bi-weekly payroll in the NYCBS payroll system.

Organize staffing: determine shift patterns and the number of staff

required to meet demand.

Conduct bi-weekly or monthly meetings to keep staff informed or all

service-related updates.

Review the performance of each team member.

Identify training needs and plan training sessions, including phone/email

scripts.

Coach team members by providing detailed feedback about qualitative and

quantitative work performance, attendance, work habits, goals, areas for

improvement, and praise/recognition in order to increase customer service.

Initiate corrective action as appropriate.

Lean to understand the call-center operations as a whole, and become familiar

with the Shoretel, PBSC and NetSuite systems.

Analyze performance trends and maintain daily, weekly, and monthly reports.

Utilize Shoretel (ACD) to monitor telephone inquiries, queue status, and

undertake queue actions.

Investigate the root cause(s) of problems, and handle the most complex customer

complaints or inquiries when escalated.

Optimize the use of call resources (including personnel).

Support strategic plans and objectives.

Effectively communicate ideas, suggestions, and solutions with the Customer

Service Manager1 3 to improve Quality Assurance.

Other duties as assigned.

Human Resources Manager Pean testified that there are 56 employees within the Call

Center. She further stated that the call center supervisors differed from the supervisors found in

other department in that the call center supervisors were hired as supervisors, and not promoted

from within. Pean noted that the call center supervisors attended two management-specific

trainings: one concerning sexual harassment, and another addressing the unionization efforts.

1 3 The record did not disclose the identity, duties, or place in the management hierarchy of the customer service

manager.

1 6

The Employer also presented call center agent Shemell Morgan as a witness. Morgan

stated that her duties included assisting customers, by email and telephone, with billing and

pricing questions and general inquiries like the location of docking stations. When asked who

she reports to, Morgan, however, did not identify any of the three individuals alleged by the

Employer to be supervisors. Instead, Morgan stated that she reported to her "manager," who she

identified as "Tina Rivera."1 4

C. SEASONAL EMPLOYEES

The Employer employs a substantial complement of seasonal employees who work

alongside its permanent staff who are both full-time and part-time employees. While the record

does not contain a precise calculation of the number of seasonal employees employed by the

Employer, the record indicates that approximately 96 employees, out of a total workforce of 24 9,

are designated as seasonal. Seasonal employees are employed in the Employer's Bicycle Fleet,

Bicycle Redistribution, Station Technicians, and Call Center Departments. Additionally, all

employees employed in the Ambassador classification are designated as seasonal. The record

indicates that the Employer's current staffing numbers closely track the Employer's 201 3

employment figures; in the fall of 201 3, the Employer had a workforce of approximately 250

individuals, 1 00 of whom were laid off at the conclusion of the peak bicycle season in October

and November 201 3.1 5

The record demonstrates that terms and conditions of employment of seasonal and

permanent employees are substantially identical. Seasonal employees receive the same rate of

pay of permanent employees in the same job title, and seasonal employees work "side by side"

with permanent employees.

In her testimony, Human Resources Manager Pean highlighted the many common

aspects of employment shared by permanent and seasonal employees. She testified, for example,

that permanent and seasonal employees are covered by same employee handbook terms, have the

same introductory, or probationary period, work under the same supervision, clock-in and clock-

out in the same manner, request time off in the same way, and wear the same uniforms and

badges. Pean also stated that the training of permanent and seasonal employees is identical, with

the exception of seasonal call center agents, who are not trained to process refunds.

Furthermore, Pean noted that while seasonal employees work on overnight and weekend shifts

more often than permanent employees, seasonal employees can be found on all shifts. Pean

stated that seasonal employees share similar skill levels and experience with permanent

employees, with the exception of those working in the associate station technician position.

1 4 Morgan appears to be referring to Tina Arniotis, identified by the Employer as the manager of the Call Center.

1 5 I note that the record indicates that the ambassadors were laid off in August and September 201 3.

1 7

With regard to the latter, Pean noted that employees working in the associate station technician

position have fewer years of experience working with computer systems. Pean also noted that

seasonal employees enjoy access to all of the same facilities as permanent employees. The only

notable difference in terms and conditions is that full-time, permanent employees receive fringe

benefits, seasonal employees and permanent part-time employees do not.

The record indicates that the seasonal employees hired in 2014 signed employment offer

confirmation letters confirming the seasonal nature of their employment. The definition for

seasonal employment contained in the letters differs slightly from that which appears in the

employee handbook, most notably in that the letters permit the Employer to estimate a length of

work season ranging from two to three months, four to five months, six to seven months, or

"other." The record indicates that the employees hired as seasonal prior to July were given

estimated work periods of six to seven months, while those hired after July were given estimated

employment periods of four to five months. Seasonal hires Shemell Morgan and Elena Crotty

testified that they understood seasonal nature of their employment at'the time of the offer and

were never informed about how they could become permanent employees or be rehired in 2015.

Human Resources Manager Pean testified regarding the hiring process for seasonal

employees in 2014. The record indicates that the Employer advertised for seasonal positions on

Craig's List and other job posting websites, and also advertised at area colleges for the

ambassador position and local technical schools for station technician openings. The record

demonstrates that the Employer amassed a workforce heavily dominated by New York City

residents. I note that the sample Craig's List job postings for the Seasonal PT Driver and Station

Technician positions contain references to Brooklyn.

The record contains limited evidence concerning the return in 2014 of the approximately

100 employees who were laid off in October and November 2013. Pean testified that several

laid-off employees reapplied for seasonal positions in 2014 and were rehired. She stated, for

example, that, "three ambassadors, three- or four ambassadors, maybe five," were rehired in

2014, out of approximately 15-20 ambassadors who worked in 2013 and a current Ambassador

workforce of 16. Pean similarly testified that at least one laid off Call Center employee, Chanel

Jones, reapplied in 2014 and was hired. Finally, Pean noted that laid-off station technician

Jonathan Bolarinwa reapplied in 2014 and was hired. In recounting the decision to rehire him,

Pean testified that, before making an offer, representatives of the Employer "pull[ed] his profile

to see what his [2013] performance was like," and spoke with permanent employees of the

Employer regarding his work history. On Bolarinwa's employment offer confirmation form, it

was explicitly noted that he was a "[r]ehire." In his testimony, Operations Director Pellegrino

similarly stated that, in deciding whether to rehire a former seasonal employee, the Employer

would take into account the fact of that the former employee had already been trained by the

18

Employer, and would also look into the applicant's performance and reliability, among other

attributes.

While Pean, several times throughout her testimony, indicated that the Employer was

undecided as to whether it would employ seasonal employees in 2015, Director of Operations

Pellegrino testified that the Employer was likely to hire seasonal employees next year. As

Pellegrino clearly stated in his testimony, "to some extent there is likely to be seasonal hiring

next year." Similarly, at another point in his testimony, Pellegrino, in response to a question

asking whether, "there's an expectation... you're going to have to have these seasonal employees

every season," stated, "Mit some capacity, yes."

Concerning the likelihood of future employment of seasonal workers, I note the record

testimony from Pean discussing some of the factors the Employer may take into account when

determining the size of its 2015 workforce, including weather-related issues and technological

improvements to the bicycle docking stations. Similarly, Technical Service Operations Manager

Justin noted that, in the event of technological improvements to docking station batteries, his

department may not need approximately seven seasonal employees who currently are responsible

solely for swapping batteries. Additionally, Bike Mechanic Lead Supervisor Mukhodinov

testified, hypothetically, that if his department eliminated a current backlog of approximately

1,900 bicycles needing repair, perhaps it could operate with only permanent employees.

Mukhodinov stressed, however, "[w]e don't know if [the bicycles in the warehouse needing

repair] will ever meet zero, because that's something that's fueled by the users every single day."

II. ANALYSIS

A. SUPERVISORS

Section 2(11) of the Act defines supervisors as follows:

any individual having authority, in the interest of the employer, to hire,

transfer, suspend, lay off, recall, promote, discharge, assign, reward or

discipline other employees, or responsibly to direct them, or to adjust their

grievances, or effectively to recommend such action, if in connection with

the foregoing the exercise of such authority is not of a merely routine or

clerical nature, but requires the use of independent judgment.

To establish that the individuals are supervisors, the party asserting supervisory status

must show: (1) that they have authority to engage in any 1 of the 12 enumerated supervisory

functions; (2) their "exercise of such authority is not of a merely routine or clerical nature, but

requires the use of independent judgment"; and, (3) that their authority is exercised "in the

19

interest of the employer." Oakwood Healthcare, Inc., 348 NLRB 686, 687 (2006). A party can

prove the requisite authority either by demonstrating that the individuals actually exercise a

supervisory function or by showing that they effectively recommend the exercise of a

supervisory function. Id. at 88. Where "putative supervisors are not shown to possess any of the

primary indicia of supervisory status enumerated in Sec. 2(11), secondary indicia are insufficient

to establish supervisory status." Golden Crest Healthcare Center, 348 NLRB 727, 731, n. 10

(2006).

In considering whether the individuals at issue here possess any of the supervisory

authority set forth in Section 2(11) of the Act, I am mindful that in enacting this section of the

Act, Congress emphasized its intention that only supervisory personnel vested with "genuine

management prerogatives" should be considered supervisors and not "straw bosses, leadmen,

set-up men and other minor supervisory employees." Chicago Metallic Corp., 273 NLRB 1677,

1688 (1985). Thus, the ability to give "some instructions or minor orders to other employees"

does not confer supervisory status. Id. at 1689. Indeed, such "minor supervisory duties" should

not be used to deprive such individual of the benefits of the Act. NLRB v. Bell Aerospace Co.,

416 U.S. 267, 280-81 (1974) (quoting Sen. Rep. No. 105,

80th

Cong. 1st Sess., at 4). In this

regard, it is noted that the Board has frequently warned against construing supervisory status too

broadly because an individual deemed to be a supervisor loses the protections of the Act. See,

e.g., Vencor Hospital Los Angeles, 328 NLRB 1136, 1138 (1999); Bozeman Deaconess

Hospital, 322 NLRB 1107, 1114 (1997).

The party asserting that an individual has supervisory authority has the burden of proof

NLRB v. Kentucky River Community Care, Inc., 532 U.S. 706, 713 (2001); Dean & Deluca New

York, Inc., 338 NLRB 1046 (2003). "[W]henever the evidence is in conflict or otherwise

inconclusive on a particular indicia of supervisory authority, [the Board] will find that

supervisory status has not been established, at least on the basis of those indicia." Phelps

Community Medical Center, 295 NLRB 486, 490 (1989); see also Brusco Tug & Barge, Inc.,

359 NLRB No. 43 (2012). Purely conclusory evidence is not sufficient to establish supervisory

status; rather the party must present evidence that the employee actually possesses the Section

2(11) authority at issue. Alternate Concepts, Inc., 358 NLRB No. 38, slip op. at 3 (2012)

("[M]ere inferences or conclusory statements, without detailed, specific evidence are insufficient

to establish supervisory authority.").

In applying the above-mentioned case law, and based on the record evidence, I conclude

that the evidence is insufficient to establish that the following individuals are supervisors within

the meaning of Section 2(11) of the Act: Bike Mechanic Supervisors Briton Malcolmson,

Humberto Facey, William Gaerre, Indio Galarza, and Carlos Rivera, Vehicle Supervisors

Aldrick Bramwell, Dyrell Epps, and Carl Johnson, Dispatch Supervisor Chris Gittens, and

Station Tech Supervisors Angel Bianchi and Murat Coskun.

20

With regard to Call Center Supervisors Jermaine Clarke, Tiandra Razor, and Selena

Brewster, the Employer has presented only paper authority. See Golden Crest Healthcare, 348

NLRB at 731 ("Job descriptions or other documents suggesting the presence of supervisor

authority are not given controlling weight. The Board insists on evidence supporting a finding of

actual as opposed to mere paper authority.").

Finally, with respect to Warehouse Supervisor Taylor, I note that the Employer has failed

to provide any specific evidence addressing his supervisory status. Furthermore, the Employer's

brief is entirely silent regarding Taylor. Accordingly, I hereby find that Taylor is an employee

within the meaning of the Act. See Golden Crest Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 728 ("The burden of

proving supervisory status rests on the party asserting that such status exists.")

The Employer, however, has established that Bike Checker Supervisor Kelly McGowan

and Dispatch Supervisor Jacob Boersma are supervisors as defined by Section 2(11) of the Act.

Accordingly, supervisors McGowan and Boersma are ineligible to vote and are hereby excluded

from the unit.

1. Authority to Hire and to Effectively Recommend Hire

The exercise of hiring authority demonstrates supervisory status. See, e.g., Kenosha

News Publishing Corp., 264 NLRB 270, 271 (1982) (individual found to be a supervisor where

he "hired all the part-time employees who work for him"). Supervisory status may also be

established where an individual effectively recommends hiring. See, e.g., IC. Penney Corp.,

347 NLRB 127 (2006) (explaining that "Nile power to effectively recommend a hire, as used in

Section 2(11), contemplates more than the mere screening of applications or other ministerial

participation in the interview and hiring process"). Evidence indicating that disputed supervisors

participate in the evaluation of probationary employees, and have the authority to determine

whether the probationary employees are retained for further training or terminated, will not, on

its own demonstrate supervisory authority. See Harbor City Volunteer Ambulance Squad, Inc.,

318 NLRB 764 (1995).

The Employer presented uncontradicted testimony that Bike Checker Supervisor Kelly

McGowan and Dispatch Supervisor/Fleet Coordinator Jacob Boersma hired some of the

employees who work in their respective departments. Accordingly, I find that the Employer has

met its burden in establishing that McGowan and Boersma are statutory supervisors under

Section 2(11) of the Act. Although the evidence suggests that fleet/field supervisors Bramwell,

Epps, and Johnson conduct evaluations of probationary employees, it is insufficient to establish

21

that they exercise the authority to effectively recommend the hire of the probationary workers.1 6

Accordingly, I do not exclude fleet/field ,supervisors Bramwell, Epps, and Johnson from the unit

on this basis.

Bike Checker Supervisor Kelly McGowan

Operations Manager Lewis testified that Bike Checker Supervisor McGowan was alone

responsible for the hiring of all bike checkers employed during the 201 4 season. The Union did

not present any evidence rebutting this assertion. In fact, the only Union witness, Bike Mechanic

Supervisor Malcolmson, testified that he, too, participated in the hiring process while serving as

bike checker supervisor in 201 3. While Malcolmson characterized his involvement as a personal

favor to Operations Manager Capezio, his testimony supports Lewis' claim that McGowan has

hiring authority as the bike checker supervisor. Although the Employer failed to present any

documentary evidence supporting its assertion, I find Lewis' uncontradicted testimony sufficient

to establish that McGowan has exercised his authority to hire and is therefore a supervisor within

the meaning of the Act.

Dispatch Supervisor/Fleet Coordinator Jacob Boersma

Operations Manager Lewis similarly provided uncontradicted testimony concerning the

hiring authority of Dispatch Supervisor/Fleet Coordinator Boersma. In his testimony, Lewis

stated that Boersma hired all of the drivers in the department. The Union failed to provide any

evidence rebutting Lewis' representation. I note that the only other individual in the department

with a coordinator title, Dispatch Supervisor/Dispatch Logistics Coordinator Marks, testified that

he, too, has hiring authority, having hired all valet attendants employed during the 201 4 season

and having participated in the hiring of seasonal, part-time dispatchers. As with McGowan,

although the Employer failed to present any documentary evidence supporting its assertion

regarding the hiring authority of Boersma, I find that the evidence is sufficient to establish that

Boersma is a supervisor within the meaning of the Act.

Field/Fleet Supervisors Aldrick Bramwell, Dyrell Epps, and Carl Johnson

Although the evidence suggests that field/fleet supervisors Bramwell, Epps, and Johnson

evaluate probationary employees, the testimonial evidence offered by Operations Manager Lewis

is too vague to establish that the field/fleet supervisors effectively recommend the hiring of

probationary employees. Lewis testified that the supervisors can determine that probationary

drivers require more ride-alongs, rides in which they are accompanied by a supervisor or more

experienced driver, before they are allowed to drive on their own. He also testified that a

16

I note that Pellegrino offered vague testimony suggesting that the bike mechanic supervisors also evaluate

probationary employees. However, Pellegrino did not suggest that the bike mechanic supervisors have the authority

to effectively recommend the hire or termination of probationary bike mechanics.

22

supervisor could "recommend that a driver is not suited to drive certain vehicles," and stated,

hypothetically, that the driver could then "be asked to... step down or they , would be terminated

if, you know ." Lewis noted, however, that no probationary driver has ever been terminated on

the recommendation of a field/fleet supervisor. Lewis also did not state what, if any, effect a

positive evaluation would have on the probationary status or pay of a new driver, and did not

explain the effect of a recommendation to continue ride-alongs.

In this regard, the authority of the field/fleet supervisors is similar to that of the field

training officers in Harbor City Volunteer Ambulance Squad, supra. In that case, the Employer

argued that the field training officers should be excluded from the unit as statutory supervisors

because they "evaluate new paramedics and make recommendations regarding whether the

paramedic is to be retained for further training, advanced to solo status, or terminated." 318

NLRB at 764. As an initial matter, the Board discounted any alleged authority to effectively

recommend termination, noting that "there have been no actual recommendations for termination

made." Id. The Board then analyzed the impact of the recommendations for continued training

or advancement to "solo status" on the continued employment of the probationary paramedics.

The Board wrote:

Here, there is no evidence that the recommendations to advance the

paramedics to solo status signal the end of their probationary status; there

is no evidence that advancing to solo status necessarily leads to permanent

employment or a change in pay status; and there is no evidence

establishing what, if any, impact a recommendation for further training has

on the employees' job status.

Id. Although the Board acknowledged that there was no dispute regarding the effectiveness of

the recommendations, it concluded that "the ability to make recommendations for extended

training or advancement to solo status... does not constitute the kind of personnel decision that

establishes supervisory authority." Id.

As in Harbor City Volunteer Ambulance Squad, the Employer has failed to present any

evidence regarding the effect of a recommendation to continue ride-alongs or advance to

unaccompanied rides. Further, because there has never been a recommendation to terminate, any

testimony in that regard is hypothetical. In this regard, I note the testimony of Director of

Operations Pellegrino, who stated that he is involved in any decision to terminate. Accordingly,

I conclude that the evidence is insufficient to establish that Field/Fleet Supervisors Bramwell,

Epps, and Johnson have the authority to effectively recommend the hiring of drivers and I will

not exclude them from the unit on this basis.

23

2. Authority to Assign

The authority to assign also demonstrates supervisory status. The Board has defined

"assign" to mean the "designating of an employee to a place (such as a location, department, or

wing), appointing an individual to a time (such as a shift or overtime period), or giving

significant overall duties, i.e., tasks, to an employee." Golden Crest Healthcare, 348 NLRB at

728, citing Oakwood Healthcare, Inc., 348 NLRB 686 (2006). "[A]d hoc instruction that [an]

employee perform a discrete task" is insufficient to establish supervisory status. Id. Further, in

order to establish authority to assign, the disputed supervisor must have "the ability to require

that a certain action be taken." Golden Crest Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 729. The Board will not

find supervisory status where the assignments are "routine" and not "based on anything other

than the common knowledge, present in any small workplace, of which employees have certain

skills and which employees work well together." Armstrong Machine Co., Inc., 343 NLRB

1149, 1150 (2004). Regarding scheduling, "the Board has observed that if the putative

supervisor's 'role in processing time-off requests was limited to assessing staffing adequacy,' it

constituted 'a routine task that did not involve independent judgment." AD Conner, 357 NLRB

No. 154 (2011), citing Pacific Coast MS. Industries Co., 355 NLRB No. 226, slip op. at fn. 13

(2010).

As discussed in full below, the Employer failed to establish that the disputed supervisors

possess the authority to assign.

Bike Mechanic Supervisors Malcolmson, Facey, Gaerre, Galarza, and Rivera

The evidence is insufficient to establish that Bike Mechanic Supervisors Briton

Malcolmson, Humberto Facey, Will Gaerre, Indio Galarza, and Carlos Rivera possess the

authority to assign. Lead Supervisor Mukhodinov testified that the bike mechanic supervisors

can determine the order of repairs to be performed and can also designate certain individuals to

perform discrete tasks, like rebuild bike wheels, as the need arises. However, rather than

demonstrating that the supervisors possess the authority to assign within the meaning of Section

2(11) of the Act, this testimony indicates that the supervisors engage in the very type of non-

discretionary, ad hoc instruction that the Board has found to be insufficient to establish

supervisory authority.

Further, the evidence does not indicate that the supervisors possess the authority to set the

schedules of mechanics. Malcolmson stated explicitly that he does not have the authority to

adjust employee schedules. While Mukhodinov testified that the supervisors "take the

availability" of the mechanics and "notify [Mukhodinov] and [Capezio] of any changes in the

bike mechanics' weekly or daily schedules," this testimony is ambiguous and does not establish

that the bike mechanic supervisors are responsible for the scheduling of the mechanics.

24

Dispatch Supervisor Gittens

Similarly, the evidence is insufficient to establish that Dispatch Supervisor Christopher

Gittens has the authority to assign within the meaning of Section 2(11) of the Act. Contrary to

the Employer's representations, the evidence does not establish that Gittens is responsible for

overnight scheduling in the department. Additionally, to the degree that Gittens is involved in

assigning individuals for "special tasks" like replacing ads or maps with stipulated supervisor

Alex Marks, the evidence suggests that Gittens has little or no discretion and merely engages in

ad hoc instruction, selecting individuals based on their willingness to work extra hours and on

"the common knowledge, present in any small workplace, of which employees have certain

skills and which employees work well together." Armstrong Machine Co., Inc., 343 NLRB at

1150. Further, Operations Manager Lewis' testimony that dispatch supervisors assign

dispatchers to coordinate vehicle pickups when the vehicles are ready is vague and does not

reflect any independent judgment on the part of Gittens or any other dispatch supervisor.

Field/Fleet Supervisor Bramwell

The evidence is also insufficient to establish that Field/Fleet Supervisor Aldrick

Bramwell assigns within the meaning of Section 2(11). Although Lewis initially testified that

Bramwell "will choose his eight or so individuals" to work on a given deployment operation,

Lewis later clarified that he, in fact, selects Bramwell's team, "based on who is scheduled to

work, [and] who [Bramwell] wants to work with him in the field." Thus, the evidence indicates

that it is Lewis, not Bramwell, who has the authority to assign individuals to deployment jobs.

Accordingly, the Employer has failed to establish that Bramwell is a supervisor within the

meaning of the Act based on his alleged authority to assign.

Station Technicians Coskun and Bianchi

Finally, the Employer has failed to establish that Station Technician Supervisors Murat

Coskun and Angel Bianchi are supervisors because they schedule station technicians and assign

them to repair projects. The testimony of Operations Manager Justin indicates that Coskun and

Bianchi do not have independent discretion to adjust the schedule of technicians or to grant

technicians extra hours. Furthermore, although the supervisors solicit individuals to volunteer

for extra hours when the department is short-staffed, there is no evidence suggesting that they

have the authority to compel someone to come in to work. Additionally, although the Employer

endeavored to argue that Coskun and Bianchi assign individuals to certain types of work, the

evidence indicates that Coskun and Bianchi, working closely with Justin, exercise little or no

discretion and merely engage in ad hoc instruction on those occasions where there is a "large

number" of one type of repair that must be completed.

25

The Employer has thus failed to establish that Bike Mechanic Supervisors Malcolmson,

Facey, Gaerre, Galarza, and Rivera, Dispatch Supervisor Gittens, and Station Technician

Supervisors Coskun and Bianchi exercise supervisory authority in assigning employees.

3. Responsibly Direct

The Board defines "responsibly to direct" as: "If a person on the shop floor has men

under him, and if that person decides that job shall be undertaken next or who shall do it, that

person is a supervisor, provided that the direction is both 'responsible'... and carried out with

independent judgment." Golden Crest Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 730, citing Oakwood

Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 691. The Board has held that, for the direction to be "responsible,"

the person directing the performance must be held accountable for the performance. Golden

Crest Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 730. Regarding this accountability element, the Board has

explained:

[T]o establish accountability for purposes of responsible direction, it must

be shown that the employer delegated to the putative supervisor the

authority to direct the work and the authority to take corrective action, if

necessary. It also must be shown that there is a prospect of adverse

consequences for the putative supervisor if he/she does not take these

steps.

Id., citing Oakwood Healthcare, 348 NLRB at 692. Even if a putative supervisor is found to

direct the performance of others, the employer will not be able to establish supervisory status

absent evidence that "the putative supervisor's rating for direction of subordinates may have,

either by itself or in combination with other performance factors, an effect on that person's terms

and conditions of employment." Id. at 731.

The Employer has failed to establish that any of the disputed supervisors responsibly

direct employees within the meaning of the Act. Even assuming that the putative supervisors

direct employees, the Employer has failed to present any specific evidence indicating that the

putative supervisors are held accountable for their direction. As in Golden Crest Healthcare, the

Employer has failed to demonstrate that any supervisor "has experience any material

consequences to her terms and conditions of employment, either positive or negative, as a result

of her performance in directing," and has not established that there is even "a prospect" of such

material consequences. Id. (italics in original). In this regard, I note that conclusory testimony,

including that of stipulated supervisor Alex Marks, who stated, "I think formally I am held