Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Climb

Uploaded by

horseradish27Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Climb

Uploaded by

horseradish27Copyright:

Available Formats

Climb Every

Mountain-

or anything

else that's

handy

Caltech's climbers keep proving that

mountains are where you find them.

On the night of February 5, 1971, Dwight Carey, a

Caltech junior, and Bob Durst, a freshman, added an

important chapter to the long, shadowy history of building

climbing at Caltech. They became the first to scale the

nine-story Millikan Library.

There is a widely held-and erroneous-impression

that students do this kind of thing as some kind of

daredevil prank. Actually, campus building climbers are

generally accomplished mountaineers and rockclimbers

who are just marking time until they can get out to the

real thing again.

There must have been building climbers on campus as

far back as the day the scaffolding for Throop Hall went

up in 1910. But it was only a couple of years ago that the

Alpine Club-the long-time haven of Caltech climbers-

published the first Climber's Guide to Caltech. The guide-

book doesn't claim to be complete, and it doesn't record

anything that happened before the 19407s7 but it is full of

information on the 1950's-a time of prodigious climbing

activity at Caltech.

Making history in one of the more unusual ways, Dwight Carey

and Bob Durst near the end of the first ascent of the nine-story

Millikan Library. Most of the distance was cowred by inserting a

grappling hook device in the ventilation grillle holes.

One of the great climbers of the fifties was Dave

Rearick, a mathematics graduate student. He is immortal-

ized in the Climber's Guide through his exploits on the

"Rearick mantlesw-the 1 Y2-inch-wide ledges, seven feet

above ground, which form a decorative motif on the

walkway arches along the older campus buildings. Rearick

is still the only man who has ever been able to pull himself

up by them and make it to a standing position. He was also

the first man to assail the south and east faces of Robinson

and to climb Spalding. His conquest of Spalding is still

considered noteworthy because he ascended the building's

layback in almost one fell up-swoop. He rested only once,

halfway up, on the belay rope, which was handled by

Howard Sturgis, '58, an active climbing enthusiast even

though he had a severe problem with acrophobia.

Rearick scaled the east face of Gates once-but only

once. When he reached the roof, he found that the trap

door was locked. There was no suitable anchor for a rappel

so he had to down-climb the route, a dangerous operation

which involved lying on a sloping ledge just below the top

and groping with one foot for a small horn on the top of

the ornamental stonework. On another memorable night

he took along a friend, Bill Woodruff, MS '60, for a climb

up Arms by the south door pillars. Woodruff got stranded

on the balcony and had to be rescued from inside by some

expert lock pickers. Rearick kept in shape for all this

activity by going over to the gym regularly, several times

a week-to practice barefoot friction ascents.

Dave Rearick is now on the faculty at the University of

Colorado, where the buildings are all the same, with

sandstone faces-presenting few aesthetic features to a

cilmber. "The only thing the students think they're good

for," he says, "is to build up their fingers."

After a hiatus in which climbing was mostly limited to

such steeplejackery as the Fleming House Mickey Mouse

Club putting seasonal folderol on the Throop cupola,

climbing came into another golden age in the late sixties.

In those days Dave Rossum, Bob Jackson, Neil Erickson,

and Keith Edwards were the nucleus of the Alpine Club.

A slight miscalculation marred the success of the first Millikan

climb, forcing Carey and Durst to pull themselves- up the last

few feet by rope. Next time, they swore, they'd do it right.

These were the great days

when there were giant

They published the Climber's Guide, which they dedicated

footprints UP the east face

-

to Charles Wilts, professor of electrical engineering who is

of Mi1likan, and

a well-known climber. Also, since he got his BS at Caltech

(1940), stayed on for an MS and a PhD, and then became Alpine Club meeting notices

A. -

a member of the faculty, Wilts is probably more

knowledgeable about every toe hold, finger space, and

were plastered 20 feet

ledge on campus than any other man at the Institute. down from the top.

Lacking transportation to rock country and anxious to

exercise their mountaineering muscles, these climbers of

the sixties concentrated on becoming the first to conquer

the newer buildings of the north campus. Beginning in

February of 1967, they mastered the south chimneys of

Booth Computing Center and the south-southeast chimney

of Steele. Then they drifted south a little and followed

Rearick's trail up Arms and the east face of Gates.

Climbs followed each other in rapid succession for the

next three months-barefoot friction ascents of the gym,

free and rope ascents of the west face of Kerckhoff, a

direct climb to the RA's balcony on the west side of

Dabney House, the north chimneys of Booth, the Winnett

chimney, a second-story traverse of Booth, and the

north face of the Gates Library. The season was polished

off in May with a neat little climb to the second-story

door of Steele.

These were the great days when there were giant foot-

prints up the east face of Millikan, and Alpine Club

meeting notices were plastered 20 feet down from the top

-all of which gave the climbers excellent rappel practice.

Last year Rossum, Edwards, and company figured out a

way for Caltech students to climb for PE credit. They

deftly assured athletic director Warren Emery that Charles

Wilts would be glad to teach such a course. Simultaneously

they informed Wilts that the PE department was in favor

of such a course and would furnish ropes and climbing

hardware. So last spring Wilts started teaching more than

a dozen students the elements of climbing-for credit.

From last year's beginners' course, a number of the

students went on to an advanced class this year. If interest

keeps up, this is the way the progression will continue.

Wilts starts his classes with skull practice on a black-

board. He outlines the physics of climbing and gets

students to appreciate its hazards-the failure of equip-

ment and/or falling. Weather permitting, the class makes

field trips one afternoon a week, the first time heading for

Stony Point, an area of sandstone cliffs near San Fernando,

where the climbs can begin from level ground. There, the

first thing the beginners do is to get the feel of another

person's weight at the end of a rope. Students pair off

into teams and take turns at this.

Climbing rocks by all possible routes is the second step.

At Stony Point there are two rocks about 20 feet high

which present different types of routes. Such short

climbing is known as "bouldering." And although the

climbs are short, they offer some of the tough and basic

aspects-how to find and assess small niches, ledges, and

rough spots, and what different kinds of weight

distribution feel like.

From instruction at Stony Point, the class moves to

granite rock at Mt. Pacifico, which is reached by going

up Angeles Crest Highway and striking inland on a rutty

dirt road. The Pacifico climbs vary from 10 to 100 feet.

The final examination for the course takes place on a

weekend at Tahquitz Peak, near Hemet. There, the climbs

are long (several hundred feet) and some are hair-raisers.

Wilts is an authority on Tahquitz climbs, being the

author of A Climber's Guide to Tahquitz, which is now

in its fourth edition.

Caltech's climbers worry a little about the reckless

oddball who may try to scale campus buildings as a

workout for some sort of ego-salving. The use-your-brains-

and-live boys have carefully researched hazards like

chemical fans on top of laboratories, and ledges made

slippery by years of chemical solvent deposits from vents.

All in all, the climbers have so far acted in a pretty

responsible way, and no one has been hurt-which makes

it possible for the administration to maintain its delicate,

unspoken agreement not to interfere with the activity.

And that's the way everyone wants to keep it.

-Janet Lansburgh

Beginners' Rock

The first time Charles Wilts (right) takes his students to the

beginners' rock at Stony Point in Chatsworth, they see what

appears to be a benign backyard boulder. Within minutes they

know it for a mocking monster that hides each finger ledge

and toehold, and frustrates all comers. Even Wilts, who knows

every square inch, treats it with respect because it is a great

climbing teacher.

Tom Weaver, a freshman mathematics

student, agreed t o climb a little way up

a Millikan Library "chimney" in broad

daylight in the interests of illustrating this

story. But since Weaver is a dedicated

climber, when he reached the point of

no return, there really was no doubt about

his decision t o go all the way. To follow

his upward course, start here and read

down each column.

We only asked him to pose for a picture-

We didn't say: ccShoot the works."

Dwight Carey and Lary Andrews, a sophomore, were on the

belay on the Millikan rooj. Weaver had inched his way up

using his back and legs, so he had plenty of arm strength t o

make it handily over the top-and demonstrate that climbers

tend t o look most unhappy when they are pleased.

You might also like

- Agistment AgreementDocument4 pagesAgistment Agreementhorseradish27No ratings yet

- Biosecurity Horse Health DeclarationDocument2 pagesBiosecurity Horse Health Declarationhorseradish27No ratings yet

- Sovereign Hill: Horse Safety InformationDocument1 pageSovereign Hill: Horse Safety Informationhorseradish27No ratings yet

- Tourist Final Equestrian Lower Res No CropsDocument2 pagesTourist Final Equestrian Lower Res No Cropshorseradish27No ratings yet

- Horses and BushfiresDocument2 pagesHorses and Bushfireshorseradish27No ratings yet

- Media Release - Mountain Climbing For CharityDocument1 pageMedia Release - Mountain Climbing For Charityhorseradish27No ratings yet

- Let's Climb A Martian Mountain: Mission X Mission HandoutDocument2 pagesLet's Climb A Martian Mountain: Mission X Mission Handouthorseradish27No ratings yet

- SEO For Dummies Bonus Search 3Document15 pagesSEO For Dummies Bonus Search 3horseradish27100% (1)

- Everest Sponsorship PackageDocument14 pagesEverest Sponsorship Packagehorseradish27No ratings yet

- Climbing Mount RomansDocument15 pagesClimbing Mount Romanshorseradish27No ratings yet

- Referee Mountain ClimbingDocument3 pagesReferee Mountain Climbinghorseradish27No ratings yet

- MT Taranaki Summit Route FactsheetDocument2 pagesMT Taranaki Summit Route Factsheethorseradish27No ratings yet

- CF Vol11 Issue1 enDocument9 pagesCF Vol11 Issue1 enhorseradish27No ratings yet

- MT Kilimanjaro-Porter PolicyDocument2 pagesMT Kilimanjaro-Porter Policyhorseradish27No ratings yet

- Tips For Safe and Enjoyable Mountain Climbing: To All Mountain Climbers From OverseasDocument2 pagesTips For Safe and Enjoyable Mountain Climbing: To All Mountain Climbers From Overseashorseradish27No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Kickball LessonDocument4 pagesKickball Lessonapi-242285968100% (2)

- Rama PDFDocument50 pagesRama PDFTrần Tín100% (1)

- Edtpa Lesson 3Document3 pagesEdtpa Lesson 3api-308328178No ratings yet

- Ted TalksDocument12 pagesTed Talksapi-355291571No ratings yet

- English: MR Shanmuganathan A/l Suppiah Principal Assistant Director EnglishDocument19 pagesEnglish: MR Shanmuganathan A/l Suppiah Principal Assistant Director EnglishlizardmanNo ratings yet

- UCSP Week 1Document2 pagesUCSP Week 1Edrin Roy Cachero Sy100% (1)

- 7-8. TG in Eng 5 Q3 Week 7 - 8Document18 pages7-8. TG in Eng 5 Q3 Week 7 - 8Queenie Anne Barroga Aspiras100% (1)

- Buzz Session PDFDocument1 pageBuzz Session PDFJosh CayabyabNo ratings yet

- THEME: Who Am I As A Senior High School Learner?Document4 pagesTHEME: Who Am I As A Senior High School Learner?Lelouch BritaniaNo ratings yet

- Debates: Lead inDocument4 pagesDebates: Lead inIELTSNo ratings yet

- Craniosacral BiodynamicsDocument12 pagesCraniosacral Biodynamicsmilero75% (8)

- Unit f326 Practical Skills in Chemistry 2 Quantitative Task SpecimenDocument14 pagesUnit f326 Practical Skills in Chemistry 2 Quantitative Task Specimenlockedup123No ratings yet

- Olympcoachmag Win 09 Vol 21 Mindset Carol DweckDocument4 pagesOlympcoachmag Win 09 Vol 21 Mindset Carol Dweckapi-254682647No ratings yet

- Job Satisfactionof Teachersat Privateand Public Secondary SchoolsDocument12 pagesJob Satisfactionof Teachersat Privateand Public Secondary SchoolsNIJASH MOHAMED PNo ratings yet

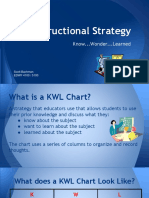

- KWL Instructional Strategy: Know... Wonder... LearnedDocument11 pagesKWL Instructional Strategy: Know... Wonder... LearnedRodelita VillalobosNo ratings yet

- Qwer AsdfDocument20 pagesQwer AsdfThetHeinNo ratings yet

- MR GMAT CriticalReasoning 6EDocument428 pagesMR GMAT CriticalReasoning 6EKsifounon Ksifounou100% (2)

- What Smart Students KnowDocument4 pagesWhat Smart Students KnowJodie RandisiNo ratings yet

- Percent Lesson PlanDocument1 pagePercent Lesson Planapi-344760154No ratings yet

- Fair Use Harbor-1Document4 pagesFair Use Harbor-1BETHNo ratings yet

- Application Form FOR AffiliationDocument9 pagesApplication Form FOR AffiliationBrilliance International AcademyNo ratings yet

- Patriotspenentry 2015Document2 pagesPatriotspenentry 2015api-207571429No ratings yet

- Advocacy PlanDocument5 pagesAdvocacy PlanjdkoontzNo ratings yet

- English 108 SyllabusDocument6 pagesEnglish 108 SyllabuscacaNo ratings yet

- Students' Perception On The Level of Competence of The Newly Hired Teachers As Impact To Their Interest To LearnDocument21 pagesStudents' Perception On The Level of Competence of The Newly Hired Teachers As Impact To Their Interest To LearnFelipe Beranio Sullera Jr.100% (1)

- Error AnalysisDocument33 pagesError AnalysisSp Seervi100% (1)

- Kimberly Forgay Resume With ReferencesDocument3 pagesKimberly Forgay Resume With Referencesapi-130459391No ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Multimedia and Interactivity 3. Web 2.0, Web 3Document6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Multimedia and Interactivity 3. Web 2.0, Web 3Twin CadungogNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 The Canadian Atlas Online - WeatherDocument9 pagesGrade 9 The Canadian Atlas Online - Weathermcmvkfkfmr48gjNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Format: George Mason University Graduate School of EducationDocument8 pagesLesson Plan Format: George Mason University Graduate School of Educationapi-302647625No ratings yet