Professional Documents

Culture Documents

David Mead CNN Story

Uploaded by

Mike KoehlerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

David Mead CNN Story

Uploaded by

Mike KoehlerCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1

7 of 17 DOCUMENTS

Copyright 1999 Cable News Network

All Rights Reserved

CNN

SHOW: NEWSSTAND: CNN & FORTUNE 20:00 pm ET

August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

Transcript # 99081100V57

TYPE: SHOW

SECTION: Business

LENGTH: 4247 words

HEADLINE: Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough

GUESTS: LEXIS-NEXIS Related Topics Full Article Related Topics Overview

This document contains no targeted Topics.

BYLINE: James Hattori, Bruce Burkhardt, Stephen Frazier

HIGHLIGHT:

David Mead's story is a cautionary tale about doing business internationally. He facilitated the payment of a bribe

from his former company, Saybolt International, to a Panamanian official and ended up in jail. Krispy Kreme does not

advertise, but customers will stand in line in the cold, in the rain, even in the middle of the night to get a Krispy Kreme

doughnut.

BODY:

THIS IS A RUSH TRANSCRIPT. THIS COPY MAY NOT BE IN ITS FINAL FORM AND MAY BE UPDAT-

ED.

ANNOUNCER: It seemed like a good idea at the time.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD STERN (ph), U.S. DISTRICT ATTORNEY FOR MASSACHUSETTS: The company made a business

decision that they would pay a bribe.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: But it blew up in his face.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAVID MEAD, FORMER PRESIDENT & CEO, SAYBOLT INTERNATIONAL: My career has been completely

destroyed.

Page 2

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: Tonight, a story of bribes and bad judgment: trying to do business overseas.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: He knew what he was doing.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: James Hattori reports on the secret world of "Dirty Deals."

It's Southern-fried...

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Try one.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: ... sugar-coated...

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: These are beautiful.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: ... and melted his heart.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It's a love story with a product. It really is.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: The Yankee who convinced Krispy Kreme there were millions to be made going west.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LINCOLN SPOOR (ph), KRISPY KREME STORE OWNER: And I called them, and I said, "You know, you have

got to give me a franchise."

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: Bruce Burkhardt on a little Southern business that's "Rolling in Dough."

CNN & FORTUNE, with Willow Bay and Stephen Frazier.

STEPHEN FRAZIER, HOST: Welcome to CNN & FORTUNE. Willow is away this week, and I'm at Joe Muggs

Newsstand in Atlanta.

We begin with a cautionary tale about doing business internationally. There are finally signs of life in some of the

economies that have been troubled for most of this year: in Asia, Latin America, even Russia. That means American

executives will be going over there and adapting to local customs in the way they operate.

But what happens in cultures where an under-the-table payment is customary and required to close a deal? That's a

practice that could land an executive in jail back home.

Here's James Hattori with one man's story. And when we first brought you this report earlier this year, jail was

exactly where the executive wound up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

JAMES HATTORI, CNN CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): Another day begins at the federal correctional institu-

tion at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Thirty-six hundred men are serving time here: mostly drug traffickers, some illegal gun

brokers, plus a former corporate president and CEO -- David Mead.

MEAD: It's hard to accept after 35 years of dedicated service to a company. My career has been completely d e-

stroyed. Rather than face a happy retirement I'm facing anything but a happy retirement now."

Page 3

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

HATTORI: Mead faces razor wire and armed guards now because of a business decision played out thousands of

miles away.

The Panama Canal was a deep channel of cash for Mead's company, Saybolt International. The Dutch firm made

its money testing petroleum, analyzing oil, marking octane levels as the freighters moved from port to port from seller

to buyer all over the world.

Mead, a British citizen, lived and worked in New Jersey and headed Saybolt operations in the West ern Hemisphere.

In 1995, Saybolt had the petroleum inspection business pretty much locked up in the vital Panama region. But

there was one big problem.

MEAD: There was need of a new location to build an office and a lab complex.

HATTORI: A critical need -- Saybolt's lab space was in jeopardy. The company had no long-term lease. The

Panamanians could come in and shut down the operation at any time, putting nearly a million dollars in equipment and

dozens of jobs at risk.

A solution arrived on Mead's computer in early 1995.

(on camera): The e-mails went back and forth between you and Mr. Dunlop (ph), the man in charge of the Panama

project.

MEAD: Correct.

HATTORI (voice-over): At first, there was only good news. Quote -- "Note some extremely positive develop-

ments taking place."

Panamanian officials offered Saybolt a permanent lease to, a new lab site in the free trade zone, Dunlop wrote.

Weeks later came the bad news. There was a string attached to the government's offer, a demand for money: a

bribe.

Saybolt's man in Panama writes to Mead, "As always in Latin America once the palms have been greased, all is

possible."

"The fee is $50,000 for the new lab site," the Panama chief writes.

"If we pay, all is ours. If we don't, we get nothing. Welcome to the Third World."

MARTIN WEINSTEIN, ATTORNEY: This is a classic situation. Usually what happens is that they get down the

road in a transaction, they get very close to closing a deal, a request is made of them, and they make a bad judgment.

HATTORI: Attorney Martin Weinstein advises multinational corporations on how to compete successfully and l e-

gally overseas. Of particular concern, the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Passed 20 years ago, the law prohibits

the payment of bribes to officials in other countries. Until recently, almost all other nations looked the other way,

passing no laws to curtail international bribery. The end result, U.S. competitors could win big global contracts with

payoffs, a business advantage American companies do without.

WEINSTEIN: I think it's a very difficult situation. If you are a salesperson or a project manager, and your pay

salary, your pay grade, your career, your whole future with the company can be determined on how well you do, if a

company places that type of pressure on you, the -- the judgments that you have to make become very, very difficult.

HATTORI (on camera): Is it like in the movies? Somebody shows up in a meeting room and passes an attache

case and the money is exchanged? Or does it...

WEINSTEIN: No. For the most part, for the most part, that scene is reserved for the movies. Most folks these

days -- most individuals and government officials have some sensitivity to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. So while

you may have instances where people want a payment, most of the time, a government official will want an interest in

the joint venture project, a business opportunity, a campaign contribution, a job for a relative.

HATTORI: If you were to take a globe and spin it and -- and randomly pick a spot in the world...

NANCY BOSWELL (ph), TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL: You'd find corruption alive and well.

Page 4

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

HATTORI (voice-over): Nancy Boswell is with Transparency International, a group that tracks corruption and its

costs.

BOSWELL: There was a recent article that estimated 200 million to 300 million in development assistance to

Uganda disappears annually. We simply can't afford that to continue.

HATTORI: Based in Berlin, Transparency International was formed six years ago when battling corruption was a

taboo topic. But recent riots in the streets of Indonesia following the collapse of the Suharto regime put battling cor-

ruption on the world's agenda.

BOSWELL: I think the Asian crisis was the final straw. Here was a region that seemed to be able to thrive despite

what many knew in terms of there was prevalent corruption, and "crony capitalism" it's now called.

When that all came apart, people recognized that the failures of transparency had a critical role in this crisis.

HATTORI: For David Mead, the crisis was one of ethics. Should he pay the bribe or face losing the Panama deal

and perhaps his job?

(on camera): What was your recommendation?

MEAD: My recommendation was that we should not do this, that it was not something that I could sanction as a

normal business matter and that I didn't feel comfortable with it. HATTORI (voice-over): In fact, a lawyer told David

Mead it would be illegal under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for an American subsidiary like Saybolt to pay a gov-

ernment official for favorable treatment. The act covers any company officer, even a resident alien like Mead.

(on camera): But it's not a crime to bribe a foreign official in the Netherlands, where Saybolt 's parent company was

based. So a man named Frerik Pluimers, Mead's boss here in Rotterdam, ordered the $50,000 payment wired directly

to Panama, bypassing the U.S. subsidiary.

With no Dutch prohibitions, Saybolt could pay the bribe and even write it off as a business expense.

(voice-over): But prosecutors say the bribe took an incriminating detour through New Jersey when Mead at U.S.

headquarters directed an employee to fly down to Panama City and arrange for a Saybolt agent to go to a bar and hand

over a plain paper bag filled with $50,000.

Federal prosecutors in Boston got wind of the bribe and tracked down a trail of evidence linking Mead to the deal

in panama.

Donald Stern, U.S. district attorney for the state of Massachusetts, led the investigation against Mead.

STERN: The e-mails, the corporate minutes, the witnesses, that made it a little bit unusual and frankly made it ea s-

ier to prosecute than might otherwise have been the case.

HATTORI (on camera): When did you find out later that you would have so me culpability?

MEAD: When I was arrested in Houston in January of 1998.

HATTORI (voice-over): Mead spent five harrowing days in the Harris County jail. He bailed out later, putting up

his house as collateral.

Mead and Frerik Pluimers in the Netherlands were charged with five counts, all stemming from the violation of the

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

(on camera): But you're the only one that's facing a jail sentence.

MEAD: I am.

HATTORI: Where's Mr. Pluimers at?

MEAD: In the Netherlands.

HATTORI: Free man.

MEAD: Yes, he's a free man. HATTORI: Free, but U.S. prosecutors say they know where Pluimers is and are a c-

tively pursuing his extradition.

So far only Mead has been prosecuted.

Page 5

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

(on camera): Do you think you were singled out by the prosecutors?

MEAD: I certainly have that feeling, yes.

STERN: And is he being singled out? No, absolutely, he was not being singled out. He was a high corporate o f-

ficial who intentionally violated the law.

This was not an accident. Nothing will send a message more t o the board rooms of this country if high officials

face the prospect of not only being prosecuted and convicted but going to jail.

HATTORI (voice-over): Mead's trial lasted six days. The jury's verdict? Guilty.

STERN: He made a business decision and his company made a business decision that they would run for luck (ph),

that they would pay a bribe hoping that they would get a return on the other end in the hopes that they would never be

prosecuted. And unfortunately for Mr. Mead and for his company, they guessed wrong.

HATTORI: On a cold and windy March morning, Mead -- surrounded by his wife and children -- arrived for sen-

tencing.

His daughter stood before the judge sobbing, saying her father's reputation and honor have been shattered. She

begged for mercy as Mead dropped his head in despair. Later, Mead rose and told the judge it was the most painful

day of his life. He admitted he should have done more to stop the bribe from taking place.

(on camera): What sentence did you receive for this crime?

MEAD: Four months of incarceration, four months of home arrest to follow. I think it's three years of probation

thereafter, and a $20,000 fine.

HATTORI: What do you think your experience and this case says to other business people who might be in the

same position?

MEAD: I think that it clearly indicates that people need to be extremely careful, that where a businessman may b e-

lieve that he's completely free of any association with matters of this type, that in actual fact, that may not be the case.

I want to get this over, do what I need to do, and get on with my life.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

FRAZIER: David Mead now has that chance to get on with his life. He was released from prison three weeks ago.

Looking back, besides landing him in jail, that $50,000 Saybolt paid was a waste of money. Panamanian officials ult i-

mately decided not to grant Saybolt a lease for that new lab site.

ANNOUNCER: Next, he gave up a career to take on a business full of holes.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SPOOR: I just had to do it. I didn't have a choice. I know that now.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANNOUNCER: Dollars and doughnuts when CNN & FORTUNE continues.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

FRAZIER: Imagine a product you never need to advertise. Just open a store, hang a sign, and customers will stand

in line, in cold, in rain, even in dark of night. That's what is happening where Bruce Burkhardt went for this report.

And it is making lots of money for a big city businessman who left the bright lights to follow his heart and his sweet

tooth.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

BRUCE BURKHARDT, CNN CORRESPONDENT (on camera): Once upon a time, on an island called Manhat-

tan, there was a man named Lincoln. Now, Lincoln was a very successful man. He was an investment banker. But the

problem was, something was missing. It wasn't money, it was dough. And this is the story of Lincoln's dream and

what he did, just because of a doughnut.

SPOOR: A little slice of paradise right here.

Page 6

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

I like that shirt.

Try one.

What a beautiful sight.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: It is. Tell me about it.

BURKHARDT (voice-over): Lincoln Spoor is either crazy in love.

SPOOR: We love this product so much.

BURKHARDT: Or just plain crazy.

SPOOR: I just had to do it. I didn't have a choice. I know that now.

BURKHARDT: The object of his affection is a 2-1/2 ounce lightly fried treat, a Krispy Kreme doughnut. Until

recently, you could only eat Krispy Kreme in the south. But thanks to its discovery by this ex-New Yorker and other

true believers, the gospel is spreading. And for Lincoln, life will never be the same, just because of a doughnut.

SPOOR: It's not just a doughnut, it's an experience.

BURKHARDT: An experience that started back in 1992. His wife told him about this great doughnut place in

Washington, D.C.

SPOOR: So I went, flew down on a Friday, and went to Krispy Kreme, and they happened to be making hot fresh

glazed, and I absolutely fell in love with it.

BURKHARDT: This is what fueled Lincoln's dream: the hot glazed original. It is Krispy Kreme's signature

doughnut and accounts for about 60 percent of yearly doughnut sales. That's 780 million hot glazed, in case you were

wondering. It's best consumed right out of the shower, a shower of hot, dripping sugar.

SPOOR: The more I found out about it, the more I wanted to be, you know, affiliated with it somehow.

BURKHARDT: You may be wondering, right about now, if this man might be a few doughnuts short of a dozen.

But know this: Lincoln Spoor is a 42-year-old Ivy League MBA. He was richly successful in high-yield investment

banking for the Bank of America.

SPOOR: I went down to see the company and I said, "gee, you know, I can raise money for you." And they said,

"no, thank you." I said, "you know, we can talk about acquiring other companies." And they said "no, thank you." So I

said, "we can lend you money." And they said "well, no, thank you."

BURKHARDT (on camera): Doesn't sound like they wanted much to do with you?

SPOOR: They wanted nothing to do with me.

BURKHARDT (voice-over): Undeterred, Lincoln came up with a new scheme. He would take Krispy Kreme

west, franchising stores in Nevada and Utah. Once again, the answer was no.

SPOOR: It was like being -- you know, you wanted to take this girl to the prom and she said no.

BURKHARDT: In reality, Krispy Kreme was not ready to franchise outside of the Southeast. And as for Lincoln,

well, he didn't have the operating experience Krispy Kreme demanded of their area developers. After all, this wasn't

just any doughnut business.

PHIL WAUGH, SENIOR V.P. OF FRANCHISING, KRISPY KREME: It's not a doughnut. That's not what it is.

It's kind of a way of life, it's a cult.

BURKHARDT: A cult that had humble beginnings, in 1937, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, still the home of

company headquarters. It's where Vernon Rudolph began making the doughnuts, behind a storefront window. His idea

was to sell them wholesale to local stores, but crowds would come to watch at the window. Rudolph may not have

realized it, but he invented doughnut theater, the hallmark of Krispy Kreme. (on camera): So this is doughnut theater?

SCOTT LIVENGOOD, CEO, KRISPY KREME: This is Krispy Kreme theater. See this in all our stores. It's like

you've got little nose prints up against the glass. You know they've been there.

Page 7

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

BURKHARDT (voice-over): Hard-core Krispy Kremers are trained, always on the lookout for that flash of neon.

That "hot doughnuts now" sign.

SPOOR: That tell you that we're making the hot, fresh glazed.

BURKHARDT: As the company grew throughout the Southeast, it was the same at all 111 stores. Turn the light

on and they will come.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I think most people do that after church. You go to church, you go to Krispy Kreme.

BURKHARDT: Growing up in Minnesota, Lincoln didn't know about this brand of southern comfort. He had his

own pleasures.

SPOOR: We'd make doughnuts from the refrigerated dough, biscuits. It was my most favorite thing.

BURKHARDT: It's not exaggerating to say Lincoln was always a dough boy. His dad was the CEO of Pillsbury.

But despite his obvious passion, Krispy Kreme still said no to Lincoln's plan. Then, one day, his wife called. Re-

member, she's the one who started this mess.

SPOOR: She said, "Krispy Kreme is coming to New York. I just saw it on 'The Today Show.'"

LIVENGOOD: That's when things really accelerated. It certainly is when all the attention intensified.

BURKHARDT: In the six years since Lincoln originally contacted the company, Krispy Kreme decided the time

was finally right to expand.

SPOOR: Finally, I decided I had to call them again, because I couldn't live without trying one more time. And I

called them and I said, you know, you have got to give me a franchise

BURKHARDT: The New York opening was a raging success.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: People were raging in New York.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: People in New York are going bananas, no pun intended, eating Krispy Kreme dough-

nuts.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: You know Krispy Kreme.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I eat Krispy Kreme doughnuts.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

BURKHARDT: ... attracting media attention coast to coast. Miraculously, it was the turning point for Lincoln.

The company finally agreed to his plan to go where no Krispy Kreme doughnut had gone before, to the West.

SPOOR: Las Vegas is America's city, in that people who visit here -- 31 million people last year -- also and looking

at the people that move here -- they moved from all over the country. Roughly 14 percent were from what we deter-

mined was Krispy Kreme country.

BURKHARDT: So it was time for Lincoln Spoor to hang up the pinstripes and sign his life on the line at a cost of

about $1 million a store for the stores he wanted. On March 3, 1998, Lincoln's dream opened its doors.

SPOOR: We had lines at 5:30, with our ambassadors then it opened, and then it died at about 10 of 6:00. And I

panicked, and I thought, oh, my god; I am going to go broke after all. And then around 6:30, 6:45...

MURIEL STEVENS, FOOD EDITOR & RESTAURANT CRITIC, "LAS VEGAS SUN": Madness -- I mean, ab-

solute madness -- a town that is so sophisticated and blase, you know been there, done that -- oh, another buffet, oh,

another restaurant, oh, another celebrity chef. A doughnut is after all only a piece of dough with a hole in the middle.

BURKHARDT: But it's about as close as "Sin City" gets to religion. Since Lincoln's store opened, thousands are

called to worship every day.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You tell people about a doughnut and they can't really comprehend, because these melt

in your mouth like butter.

Page 8

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: It's our third trip down here now, for doughnuts?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes -- our third trip down from Salt Lake.

BURKHARDT (on camera): You drove from Salt Lake City?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Now we're headed back.

BURKHARDT: For Krispy Kreme?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Krispy Kreme Doughnuts.

BURKHARDT (voice-over): A six-hour drive from Utah for a doughnut. Theirs is not an isolated case.

LIVENGOOD: This thing has sort of taken on a life of its own.

BURKHARDT: If the current projections are anything close to reality, Krispy Kreme will be rolling in the dough.

LIVENGOOD: Krispy Kreme will be a billion-dollar business. I think within 10 years, Krispy Kreme will have at

least 500 stores nationally.

BURKHARDT: Currently, each store averages between $1.5 million and $2.5 million a year in revenue -- that's per

store. Now, multiply that times 42 stores.

Forty-two stores is what Roger Glickman and his fellow investors have committed to here in Southern California.

(on camera): You're going to make a lot of money.

ROGER GLICKMAN (ph), KRISPY KREME INVESTOR: Well, I just want to make a lot of doughnuts, and the

money will follow.

BURKHARDT: These are beautiful.

(voice-over): Lincoln and corporate executives came to the opening of Roger's first store in La Habra, Cali fornia,

and the opening frenzy, with lines forming in the predawn hours, proved, once again, the inner child in many people

will do anything...

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Just because of a doughnut.

BURKHARDT: It all looks like great fun, now. But control issues may lie ahead, as the protective corporate par-

ent adopts some savvy kids, like Lincoln and Roger, into the family.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: What you want to do is incorporate the elements into the prototype.

SPOOR: You know, have a little darker green -- is that possible?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I don't know. That's the old Krispy Kreme green.

BURKHARDT: Sometimes the new kids have their own ideas about how to do things.

SPOOR: There were some things about the design that we felt very, very strongly about -- the chairs, the tile -- the

tile everywhere -- the merchandise display case.

BURKHARDT: It's not something that Krispy Kreme is used to.

(on camera): It seems to me, there's bound to be an element -- at first, anyhow -- of, hey, we're not going to let this

Yankee come in and tell us how to do what we've been doing since 1937.

SPOOR: There's no doubt about that. I mean, I'm sure there are people at the company that would just prefer I go

away.

BURKHARDT (voice-over): But whatever their differences, something bigger, or smaller, unites them.

SPOOR: It's everything I am right now.

BURKHARDT (on camera): And it can actually elicit tears? SPOOR: Oh, my God, yes, absolutely.

BURKHARDT (voice-over): That's what dreams do to people, just because of a doughnut.

Page 9

Dirty Deals; Rolling in Dough CNN August 11, 1999; Wednesday 8:30 pm Eastern Time

SPOOR: It's a wonderful way of making people happy. And that sounds so stupid, and corny, and dumb, and id i-

otic and phony, and it's not.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

FRAZIER: Lincoln Spoor just opened his third Krispy Kreme store. It, too, is in Las Vegas. Krispy Kreme now

has 148 stores in 26 states. Its sales rank 111th among U.S. restaurant franchises. And according to "Restaurants and

Institutions" magazine, which tracks these things, Dunkin' Donuts, which ranks 11th, takes in about ten times as much

money.

Some people call the occupant of this week's "Cool Digs" a renaissance man. Check out the combination of art,

literature, music and sports memorabilia in this office, and guess who works here.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

FRAZIER (voice-over): Inside this office, a man gets paid a lot of money to think about what women really want.

He gets inspiration from paintings of beautiful ladies. Among his other interests, Latin culture, African art and the

blues. But this CEO isn't singing the blues these days. His company earned $105 million last year. He likes jazz,

too, Quincy Jones, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, among his favorites. Masks from Papua New Guinea. He also tra v-

eled to Africa with President Clinton last year. That's Jackie Robinson's autograph, one of the boss's heroes. Lots of

books on the radiator, Arthur Ashe, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Lillian Vernon. Did she give the boss pointers for his

booming mail order business? A football signed by the University of New Mexico Lobos. The boss went there on a

full football scholarship. He never got a Heisman, but he did won a lot of awards, including this NAACP Image

Award. He helps 7 million women improve their images every month. So, who is the man women love to love? The

answer when we come back.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

FRAZIER: So, who is the executive with masks from New Guinea, and Jackie Robinson's autograph? He's Ed-

ward Lewis, chairman of Essence Communications. Even though "Essence" magazine bills itself as the preeminent

lifestyle magazine for today's African-American woman, about one-third of its seven million monthly readers are men.

That's all for this week.

Next Wednesday, an update on investing in Russia. We follow one Russian fund that went from being the world's

top dog to its biggest dog, overnight. Not the same thing. Guess where it ranks now, next Wednesday at 8:00 Eastern,

5:00 and 10:00 p.m. Pacific.

I'm Stephen Frazier. Willow's back next week. For all of us at CNN & FORTUNE, good night from the news-

stand.

TO ORDER A VIDEO OF THIS TRANSCRIPT, PLEASE CALL 800-CNN-NEWS OR USE OUR SECURE

ONLINE ORDER FORM LOCATED AT www.fdch.com

LOAD-DATE: August 11, 1999

You might also like

- Dumb Money: How Our Greatest Financial Minds Bankrupted the NationFrom EverandDumb Money: How Our Greatest Financial Minds Bankrupted the NationRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Top 15 Economic 'Truth' Documentaries - Zero HedgeDocument21 pagesThe Top 15 Economic 'Truth' Documentaries - Zero HedgeZohaib AslamNo ratings yet

- Mike Whitney - If The Coming Wave Of: See RICO CaseDocument9 pagesMike Whitney - If The Coming Wave Of: See RICO CaseAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- License To Fail: The Business Mistakes Of Bond VillainsFrom EverandLicense To Fail: The Business Mistakes Of Bond VillainsNo ratings yet

- Celente: The Stimulus Game Is Up US FDIC Shuts Down 7 Banks, 2010 Total Now 37Document6 pagesCelente: The Stimulus Game Is Up US FDIC Shuts Down 7 Banks, 2010 Total Now 37Albert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- RAW DIG2 GIUSTRA Johnny Depp & Adam Waldman Backstory Links EtcDocument9 pagesRAW DIG2 GIUSTRA Johnny Depp & Adam Waldman Backstory Links EtcDGB DGBNo ratings yet

- Dow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesDocument6 pagesDow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- You Got Screwed!: Why Wall Street Tanked and How You Can ProsperFrom EverandYou Got Screwed!: Why Wall Street Tanked and How You Can ProsperRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- David J. Stern & Andrew Lee Fivecoat, Florida Bar 0122068Document34 pagesDavid J. Stern & Andrew Lee Fivecoat, Florida Bar 0122068Albertelli_LawNo ratings yet

- The Almighty Dollar: Follow the Incredible Journey of Single Dollar to See How the Global Economy Really WorksFrom EverandThe Almighty Dollar: Follow the Incredible Journey of Single Dollar to See How the Global Economy Really WorksNo ratings yet

- The Revolution Will Be DigitizedDocument4 pagesThe Revolution Will Be DigitizedToronto Star100% (1)

- Chapter 7Document8 pagesChapter 7mithunNo ratings yet

- Dow Nasdaq S&P 500: Stocks/Gold ComparisonDocument5 pagesDow Nasdaq S&P 500: Stocks/Gold ComparisonAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Global Financial CrisisDocument3 pagesGlobal Financial Crisisrizal2uNo ratings yet

- Final World Conservation Bank ParagraphsDocument3 pagesFinal World Conservation Bank Paragraphsgeorgehunt1100% (1)

- 01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriDocument3 pages01-31-08 CD-Memo To The FBI - Expand The Probe of Economic CriMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- The Credit Crunch DiariesDocument101 pagesThe Credit Crunch DiariesDavidLascellesNo ratings yet

- Dow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesDocument4 pagesDow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Once Bullish, Contrarian Jim Grant Likes Cash Now: AdchoicesDocument4 pagesOnce Bullish, Contrarian Jim Grant Likes Cash Now: AdchoicesBrandywine84No ratings yet

- Problems of The World: They Want A Civil WarDocument5 pagesProblems of The World: They Want A Civil WarMatt KucusudkoiNo ratings yet

- Net Insider Transactions Cycle Back To Selling How Have U.S. Stocks Defied Gravity For So Long?Document10 pagesNet Insider Transactions Cycle Back To Selling How Have U.S. Stocks Defied Gravity For So Long?Albert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Wall Street Is To BlameDocument3 pagesWall Street Is To BlameUruk SumerNo ratings yet

- April 292010 PostsDocument5 pagesApril 292010 PostsAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- DoomofFed Rosenberg12 08Document2 pagesDoomofFed Rosenberg12 08Carl MullanNo ratings yet

- CONFIRMED: Trillion Dollar Lawsuit That Could End Financial Tyranny - David WilcockDocument128 pagesCONFIRMED: Trillion Dollar Lawsuit That Could End Financial Tyranny - David WilcockZach Royer100% (2)

- Dow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesDocument7 pagesDow Nasdaq S&P 500: (Video) Gold SurgesAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document5 pagesChapter 3LiloNo ratings yet

- February 112010 PostsDocument4 pagesFebruary 112010 PostsAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- DRUDE - A Novel Approach To Corruption and Investment Arbitration (2018)Document54 pagesDRUDE - A Novel Approach To Corruption and Investment Arbitration (2018)senidaNo ratings yet

- CONFIRMED: The Trillion-Dollar Lawsuit That Could End Financial TyrannyDocument89 pagesCONFIRMED: The Trillion-Dollar Lawsuit That Could End Financial Tyrannyбольшой всегдаNo ratings yet

- Banks Closed in Puerto Rico, Mich., Mo., Wash. (AP) : Sell in May and Go Away!Document5 pagesBanks Closed in Puerto Rico, Mich., Mo., Wash. (AP) : Sell in May and Go Away!Albert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Satan's Agenda For Disclosure - First Contact - Parts 5 6 PDFDocument17 pagesSatan's Agenda For Disclosure - First Contact - Parts 5 6 PDFjannakarl0% (1)

- Joe Stiglitz: U.S. Root of World Financial ChaosDocument9 pagesJoe Stiglitz: U.S. Root of World Financial ChaosAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- The Gold Standard 37 Jan 14Document12 pagesThe Gold Standard 37 Jan 14ulfheidner9103No ratings yet

- Wild Weekly Wrap Up: Super Secret Plays For A Mindless Market DavisDocument7 pagesWild Weekly Wrap Up: Super Secret Plays For A Mindless Market DavisAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Best Company, Inc.: LASE 1.4Document15 pagesBest Company, Inc.: LASE 1.4davidwijaya1986No ratings yet

- Inside Job PDFDocument87 pagesInside Job PDFAriel MarascalcoNo ratings yet

- Project ProphecyDocument54 pagesProject ProphecyAnonymous m6yoprE9z100% (1)

- Senate Hearing, 112TH Congress - The Next Ten Years in The Fight Against Human Trafficking: Attacking The Problem With The Right ToolsDocument60 pagesSenate Hearing, 112TH Congress - The Next Ten Years in The Fight Against Human Trafficking: Attacking The Problem With The Right ToolsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The China Hustle: The Millionaire Financial Scam That Started in 2008 and Still Hurts: AbstractDocument3 pagesThe China Hustle: The Millionaire Financial Scam That Started in 2008 and Still Hurts: AbstractMARIEL0% (1)

- More Spin, Merger Bubble Activity Helps Lift Stocks For 3rd Day (AP)Document5 pagesMore Spin, Merger Bubble Activity Helps Lift Stocks For 3rd Day (AP)Albert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Inside Job ScriptDocument34 pagesInside Job Scriptlugonian8362No ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oversight of The Property and Casualty Insurance IndustryDocument103 pagesSenate Hearing, 110TH Congress - Oversight of The Property and Casualty Insurance IndustryScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dow Nasdaq SP 500: Stocks/Gold ComparisonDocument5 pagesDow Nasdaq SP 500: Stocks/Gold ComparisonAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Bernie MadoffDocument4 pagesBernie MadoffSolarDataNo ratings yet

- Obama Speech State of The UnionDocument15 pagesObama Speech State of The UnionEleonora MihailaNo ratings yet

- 18Document8 pages18utgiNo ratings yet

- MGT301 Assignment Abhinav Singhal 2010111069Document3 pagesMGT301 Assignment Abhinav Singhal 2010111069Abhinav SinghalNo ratings yet

- Cases Against Wall Street Lag Despite Holder's Vow To Fight Fraud..Document43 pagesCases Against Wall Street Lag Despite Holder's Vow To Fight Fraud..Albert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Rickards The Global Elites' Secret Plan For The Next Financial CrisisDocument4 pagesRickards The Global Elites' Secret Plan For The Next Financial CrisisOCHETE AMNo ratings yet

- White Collar Crime in South and Central America - Diego Zysman QuirósDocument18 pagesWhite Collar Crime in South and Central America - Diego Zysman QuirósÁngela Gutiérrez GiraudoNo ratings yet

- Lehman Brothers The Bank That Bust The World Documentary 360p 22 02 2024Document20 pagesLehman Brothers The Bank That Bust The World Documentary 360p 22 02 2024Erica JoannaNo ratings yet

- Gofredo, Jericho L.Document2 pagesGofredo, Jericho L.Jericho GofredoNo ratings yet

- Return of The No-Volume Melt-Up: Making Millions From Mowing LawnsDocument60 pagesReturn of The No-Volume Melt-Up: Making Millions From Mowing LawnsAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Reflection of The Movie Informant - RevisedDocument3 pagesReflection of The Movie Informant - RevisedBhavika BhatiaNo ratings yet

- March 132010 PostsDocument6 pagesMarch 132010 PostsAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- Finance QuotationsDocument8 pagesFinance QuotationsNastya SelivanovaNo ratings yet

- NG Jury InstructionsDocument72 pagesNG Jury InstructionsMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Teva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Document38 pagesTeva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaDocument18 pagesU.S. v. Enrique Pere YcazaMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaDocument21 pagesU.S. v. Antonio Pere YcazaMike Koehler100% (1)

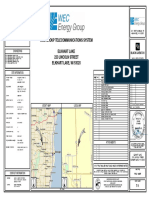

- Wec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Document18 pagesWec Group Telecommunications System Elkhart Lake 220 Lincoln Street Elkhart Lake, Wi 53020Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Proposed FCPA AmendmentsDocument13 pagesProposed FCPA AmendmentsMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Teva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusDocument47 pagesTeva Whistleblower Writ of MandamusMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Swedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsDocument99 pagesSwedish Court Decision Re Telia ExecsMike Koehler100% (2)

- SEC v. CoburnDocument17 pagesSEC v. CoburnMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Lyons Bribery ChargesDocument13 pagesLyons Bribery ChargesHNN100% (10)

- Chatburn IndictmentDocument15 pagesChatburn IndictmentMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Lambert IndictmentDocument24 pagesLambert IndictmentJacciNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Document31 pagesU.S. v. Ho (DOJ Response Brief)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Document3 pagesU.S. v. Transport Logistics Int'l (Order)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- U.S. V Ho Motion To DismissDocument27 pagesU.S. V Ho Motion To DismissMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Document28 pagesU.S. v. Bahn (Sentencing)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Africo Resources Ltd. LetterDocument26 pagesAfrico Resources Ltd. LetterMike Koehler100% (1)

- Canada Should Say No To DPAsDocument19 pagesCanada Should Say No To DPAsMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- SEC Opposition Brief To Cohen - Baros Motion To DismissDocument110 pagesSEC Opposition Brief To Cohen - Baros Motion To DismissMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Sandra Moser RemarksDocument6 pagesSandra Moser RemarksMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- SEC v. Chiquita Brands (FCPA)Document6 pagesSEC v. Chiquita Brands (FCPA)Mike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- Davis Polk Bio-Rad ReportDocument20 pagesDavis Polk Bio-Rad ReportMike KoehlerNo ratings yet

- All 8-23Document309 pagesAll 8-23Ken KuhlkenNo ratings yet

- Essentials of TradingDocument118 pagesEssentials of TradingGpalau100% (2)

- Quartz 2020 Media Kit PDFDocument10 pagesQuartz 2020 Media Kit PDFJamil Diab100% (1)

- Twitter SlidwsDocument24 pagesTwitter SlidwsOnsa piarusNo ratings yet

- Writing An Email/ LetterDocument4 pagesWriting An Email/ LetterRinawati Mohd Nawawi100% (1)

- S02 #2 Stud - Intravia 2017 - Investigating The Relationship Between Social Media Consumption and Fear of Crime ..Document11 pagesS02 #2 Stud - Intravia 2017 - Investigating The Relationship Between Social Media Consumption and Fear of Crime ..Lissa LucastaNo ratings yet

- YTC - Lance Beggs - Price Action (Eng)Document309 pagesYTC - Lance Beggs - Price Action (Eng)Mr3chi71% (31)

- Kalsched - Intersections of Personal Vs Collective Trauma During The COVId 2019 PandemicDocument20 pagesKalsched - Intersections of Personal Vs Collective Trauma During The COVId 2019 PandemicomargibramNo ratings yet

- Goebbels' Principles of PropagandaDocument25 pagesGoebbels' Principles of PropagandaHadi Kobaysi100% (8)

- EnglishFile4e Intermediate TG PCM Grammar 8BDocument1 pageEnglishFile4e Intermediate TG PCM Grammar 8BJoão Pedro Silva e SoaresNo ratings yet

- Lucy Was Brushing Her Teeth.: I. What Were These People Doing at Six o Clock Yesterday Evening? ExampleDocument4 pagesLucy Was Brushing Her Teeth.: I. What Were These People Doing at Six o Clock Yesterday Evening? ExampleМаринаNo ratings yet

- Meet Afghanistan's Only Female Tour Guide - CNN TravelDocument4 pagesMeet Afghanistan's Only Female Tour Guide - CNN Travellullaby girlNo ratings yet

- (Media Management and Economics Series) Ulrike Rohn, Tom Evens - Media Management Matters - Challenges and Opportunities For Bridging Theory and Practice (2020, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocument281 pages(Media Management and Economics Series) Ulrike Rohn, Tom Evens - Media Management Matters - Challenges and Opportunities For Bridging Theory and Practice (2020, Routledge) - Libgen - Lisamar aliNo ratings yet

- MIL Lesson 3Document4 pagesMIL Lesson 3ItzKenMC INo ratings yet

- Assembly ScriptDocument4 pagesAssembly ScriptAahhanNo ratings yet

- Shadowrun 4E - Missions - Rally Cry (Buried Underground, Part 2)Document31 pagesShadowrun 4E - Missions - Rally Cry (Buried Underground, Part 2)Pici PiciNo ratings yet

- H-Net - The History of The Caribbean (Nicola Foote, Spring 2007) - 2015-04-04Document23 pagesH-Net - The History of The Caribbean (Nicola Foote, Spring 2007) - 2015-04-04Bianka RoseNo ratings yet

- Ethical Journalism Book Chapter 1Document19 pagesEthical Journalism Book Chapter 1Dumitrita UngureanuNo ratings yet

- Voices Intermediate U02 Test Answer KeyDocument4 pagesVoices Intermediate U02 Test Answer KeyDouglas EkonNo ratings yet

- PGN July 12-18, 2019Document32 pagesPGN July 12-18, 2019Philly Gay NewsNo ratings yet

- DHS v. New York Motion To Lift or Modify StayDocument261 pagesDHS v. New York Motion To Lift or Modify StayWashington Free BeaconNo ratings yet

- European Medicines AgencyDocument11 pagesEuropean Medicines AgencyDeenNo ratings yet

- Social Responsibility TheoryDocument6 pagesSocial Responsibility Theoryali asaed50% (2)

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 6-5-20Document12 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 6-5-20The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Video News Release Script FinalDocument1 pageVideo News Release Script Finalapi-573598932No ratings yet

- Planning and Design Guidelines For Small Craft Harbors - ASCEDocument3 pagesPlanning and Design Guidelines For Small Craft Harbors - ASCEFahmy ArdhiansyahNo ratings yet

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 3-22-20Document20 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 3-22-20The DispatchNo ratings yet

- Was Hinkley The Reagan Assassination Hit Man For The Shadow GovernmentDocument5 pagesWas Hinkley The Reagan Assassination Hit Man For The Shadow GovernmentAnonymous m6yoprE9zNo ratings yet

- Judgment C8 (Canal 8) v. France - No Violation of Article 10 in Sanctions Imposed by Superior Audiovisual Council (CSA)Document5 pagesJudgment C8 (Canal 8) v. France - No Violation of Article 10 in Sanctions Imposed by Superior Audiovisual Council (CSA)Timotej KlincNo ratings yet

- Cold Room Price in Nigeria by Akpo Oyegwa Refrigeration Company (AORC)Document3 pagesCold Room Price in Nigeria by Akpo Oyegwa Refrigeration Company (AORC)PR.comNo ratings yet

- Our Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownFrom EverandOur Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (86)

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryFrom EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.From EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (45)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Witness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonFrom EverandWitness: For the Prosecution of Scott PetersonRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (44)

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodFrom EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1802)

- A Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersFrom EverandA Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (54)

- The Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenFrom EverandThe Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (37)

- Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodFrom EverandTinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of HollywoodNo ratings yet

- True Crime Case Histories - (Volumes 4, 5, & 6): 36 Disturbing True Crime Stories (3 Book True Crime Collection)From EverandTrue Crime Case Histories - (Volumes 4, 5, & 6): 36 Disturbing True Crime Stories (3 Book True Crime Collection)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Restless Souls: The Sharon Tate Family's Account of Stardom, the Manson Murders, and a Crusade for JusticeFrom EverandRestless Souls: The Sharon Tate Family's Account of Stardom, the Manson Murders, and a Crusade for JusticeNo ratings yet

- The Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalFrom EverandThe Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorFrom EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (77)

- The Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftFrom EverandThe Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftNo ratings yet

- Diamond Doris: The True Story of the World's Most Notorious Jewel ThiefFrom EverandDiamond Doris: The True Story of the World's Most Notorious Jewel ThiefRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (18)

- In My DNA: My Career Investigating Your Worst NightmaresFrom EverandIn My DNA: My Career Investigating Your Worst NightmaresRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Perfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthFrom EverandPerfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (68)

- Blood Brother: 33 Reasons My Brother Scott Peterson Is GuiltyFrom EverandBlood Brother: 33 Reasons My Brother Scott Peterson Is GuiltyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (57)

- What the Dead Know: Learning About Life as a New York City Death InvestigatorFrom EverandWhat the Dead Know: Learning About Life as a New York City Death InvestigatorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (72)

- Bloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyFrom EverandBloodlines: The True Story of a Drug Cartel, the FBI, and the Battle for a Horse-Racing DynastyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Terror by Night: The True Story of the Brutal Texas Murder that Destroyed a Family, Restored One Man's Faith, and Shocked a NationFrom EverandTerror by Night: The True Story of the Brutal Texas Murder that Destroyed a Family, Restored One Man's Faith, and Shocked a NationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (118)

- The Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing MasterpieceFrom EverandThe Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing MasterpieceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenFrom EverandThe Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (78)

- Cold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderFrom EverandCold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (53)