Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ContentServer 2

Uploaded by

Ni Wayan Ana PsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ContentServer 2

Uploaded by

Ni Wayan Ana PsCopyright:

Available Formats

Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Vol. 39, No.

3, May 2011

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are well-

known causative factors of posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). As the name

suggests, manifestations of PRES are usually

transient and complete recovery is the rule. Most

cases of PRES reported in the obstetric literature

involve postpartum patients, with only a few cases

of antepartum PRES

1-4

. We report a primigravid

woman who presented with an abrupt onset of

eclampsia and PRES. She was managed with

supportive care, labour was induced and maternal

and neonatal outcomes were good. The challenges

posed by PRES occurring in the antepartum period,

as opposed to non-obstetric or postpartum PRES,

are discussed.

CASE HISTORY

A 25-year-old primigravid woman with eight

months of amenorrhoea presented with history of

a fall at home, six hours before admission to the

emergency department of our hospital. Her husband

gave the history of fve episodes of generalised

tonic-clonic convulsions over a period of three hours

and three episodes of vomiting. She had received

regular antenatal checkups and her examination

during the last visit (one month before the episode)

had not revealed any abnormalities.

On examination in the emergency department,

she was conscious, disoriented and restless. Both

her pupils were 3 mm in size and reacting to light.

There was a lacerated wound of the scalp over the

occipital area. She was afebrile, pulse rate was

90 bpm, blood pressure 184/140 mmHg, respiratory

rate 38 breaths/minute and arterial oxygen saturation

(SpO

2

) 99% on room air. There was no pedal oedema

and central cardiovascular system and respiratory

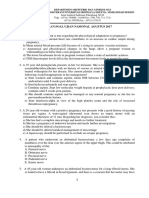

system fndings were normal. An urgent non-contrast

computed tomography (CT) scan of the head,

performed under sedation (total dose of propofol

60 mg), showed ill-defned hypodense areas in both

parieto-occipital lobes and the right temporal lobe,

involving the cortex and subcortical white matter

(Figure 1). There was no intracranial haemorrhage.

Based on these fndings, PRES and superior sagittal

sinus thrombosis were considered the differential

diagnosis.

The patient was transferred to the surgical

intensive care unit, where on admission she was

restless, with pulse rate 84 bpm and blood pressure

of 196/124 mmHg. She was administered intra-

venous fentanyl 100 g, midazolam 1 mg and labetalol

* M.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology.

D.M.R.D., D.N.B., Assistant Professor, Department of Radiodiagnosis.

M.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

M.D., D.N.B., Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology.

** M.D., Professor and Head, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

M.D., Professor and Head, Department of Anaesthesiology.

Address for correspondence: Dr H. V. Hegde, Department of

Anaesthesiology, Shri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of

Medical Sciences and Hospital, Dharwad, Karnataka 580 009, India. Email:

drharryhegde@yahoo.co.in

Accepted for publication on December 9, 2010.

A rare case of antepartum posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome

H. V. HEGDE*, P. B. PATIL, R. RAMESHKUMAR, T. H. SUNITA, M. T. BHAT*, R. M. DESAI**,

P. R. RAO

Departments of Anaesthesiology, Radiodiagnosis, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Shri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of

Medical Sciences and Hospital, Dharwad, Karnataka, India

SUMMARY

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are well-known causative factors of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

(PRES). There are only a few reported cases of antepartum PRES. We report a 25-year-old primigravid woman

who presented with eight months of amenorrhoea and an abrupt onset of eclampsia associated with a history of a

fall. A computed tomography scan ruled out intracranial haemorrhage and PRES was diagnosed. She responded

well to supportive care, labour was induced and maternal and neonatal outcomes were good. Antepartum PRES

poses different challenges to those of PRES in non-obstetric or postpartum patients, because of the additional

management aspects required to ensure foetal wellbeing. We were posed with a difficult decision about the

disadvantages of caesarean section versus those of vaginal delivery in our patient.

Key Words: posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, eclampsia, antepartum, seizures

Anaesth Intensive Care 2011; 39: 499-502

500

H. V. HEGDE, P. B. PATIL ET AL

Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Vol. 39, No. 3, May 2011

20 mg. The right radial artery was cannulated

and intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring

initiated. Magnesium sulphate 5 g was administered

intravenously over 10 minutes, followed by an

infusion at 1 g/hour. The blood pressure reduced to

166/110 mmHg. Intravenous betamethasone 12 mg

was administered and repeated after 12 hours to

accelerate foetal lung maturity

5

.

Her baseline investigations were haemoglobin

128 g/l, leucocyte count 13,830 /mm

3

(neutrophils

88%, lymphocytes 6%), platelet count 131,000 /mm

3

,

blood sugar 5.1 mmol/l, serum Na

+

134 mmol/l,

serum K

+

4.3 mmol/l, blood urea 7.8 mmol/l, serum

creatinine 97.2 mol/l, uric acid 0.5 mmol/l, urinary

protein 4

+

, prothrombin time 12.8 seconds (control

12.2 seconds), international normalised ratio 1.04,

activated partial thromboplastin time 28 seconds

(control 30 seconds) and liver function tests were

normal. A bedside obstetric ultrasound showed a live

foetus with estimated gestational age of 31 weeks

and body weight of 1.1 kg (<5th percentile of the

expected weight, representing severe intrauterine

growth retardation). On vaginal examination,

the cervix was 50% effaced, 2 cm dilated and

membranes were intact. Her blood pressure

remained in the range of 152/106 to 170/118 mmHg

and pulse rate 70 to 85 /minute over the next three

hours. An ophthalmic evaluation showed a normal

fundus.

While preparations for caesarean section were

made, her sensorium improved and four hours after

admission to the surgical intensive care unit she

started obeying commands. At review, it was decided

to induce labour, in view of the severe intrauterine

FIGURE 1: Computed tomography scan on admission. Ill-defined

hypodense areas in bilateral parieto-occipital and right temporal

lobes.

growth retardation and prematurity, good Bishop

Score, adequate control of blood pressure and no

signs of maternal deterioration. Induction of labour

was with misoprostol 50 g vaginally. She had

spontaneous rupture of membranes four hours later

and contractions were augmented with an oxytocin

infusion. The labour progressed smoothly, the foetus

being monitored continuously by cardiotocograph.

The woman was delivered of a male baby (weight

950 g) vaginally, 14 hours after induction. The

baby cried soon after the birth and in the neonatal

intensive care unit was managed with oxygen

administered via hood, antibiotics and intravenous

fuids. He developed sepsis on the third day but was

treated successfully and discharged on the 25th day

with a weight of 1.35 kg.

The patients urine output was 800 ml in the frst

12 hours and her blood pressure was between

150/106 and 170/118 mmHg during the active phase

of labour. She did not receive analgesia during

the course of labour as she was unable to give

adequate feedback regarding the pain. Her blood

pressure gradually reduced to 140/100 mmHg while

remaining on the magnesium sulphate infusion and

also receiving intravenous labetalol 20 mg six hourly.

Serum magnesium level was 1.5 mmol/l. Magnesium

sulphate and labetalol were stopped 24 hours after

delivery and oral nifedipine 10 mg twice daily was

started. She was transferred to the ward on the third

day. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

performed on the eighth day (Figure 2) showed near-

complete resolution of the lesions seen on CT at

admission and also excluded superior sagittal sinus

thrombosis. The patient was discharged on day 10,

FIGURE 2: Follow-up magnetic resonance image eight days later,

showing near-complete resolution of the lesions seen in Figure 1.

501

CASE REPORT

Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Vol. 39, No. 3, May 2011

showing complete neurological recovery. She gave

consent for publication of this report.

DISCUSSION

PRES has been reported in a wide variety of clinical

settings. Presentation is varied but the most common

feature has been hypertension. Precipitating factors

6

include abrupt hypertension, immunosuppressant

drug use, infection, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia and

renal disease. Rarely, intrathecal morphine

7

and

intravenous caffeine therapy for post lumbar puncture

headache

8

have also been implicated as causative

factors.

Other presenting symptoms include seizures,

encephalopathy, visual symptoms and headache

6

.

Although most patients recover completely, a 27-year-

old woman in the 38th week of pregnancy who

developed persistent hypertension, complicated by

fatal subarachnoid haemorrhage, has been reported

1

.

PRES may also be associated with intracerebral

haemorrhage, which is generally considered an

atypical fnding. The clinical outcome of PRES with

associated intracerebral haemorrhage appears more

variable

9

.

Although PRES classically manifests in parieto-

occipital white or grey matter, the temporal lobes,

frontal lobes, brainstem and cerebellum may be

involved

10

. The posterior cerebral circulation is

thought to be more susceptible, possibly because

of lower sympathetic innervation than that of the

internal carotid artery territory, with a consequent

reduction in autoregulation of already impaired areas

of circulation

11

. The exact pathogenesis of PRES

remains incompletely understood and is likely

multifactorial. The most likely mechanism in an

eclamptic patient is vasogenic oedema secondary to

an acute increase in arterial blood pressure, which

overwhelms the autoregulatory capacity of the

cerebral vasculature causing arteriolar vasodilation,

endothelial dysfunction and interstitial extravasation

of fuid

2,10

. In a retrospective analysis of 120

patients, Fugate et al

12

reported a high prevalence

of autoimmune and infammatory conditions in

PRES patients, suggesting that endothelial dys-

function may lie at the core of its pathophysiology.

PRES is a clinical and radiological diagnosis.

Clinical fndings are not suffciently specifc but

neuroimaging is often characteristic

13

. It is important

to distinguish PRES from acute stroke, to guide

treatment

14

. Even though MRI is considered the

investigation of choice to diagnose PRES

15,16

, this

would have required either deep sedation or general

anaesthesia during the procedure, thus exposing our

patient to the risks of aspiration, haemodynamic

fuctuation and the direct and indirect effects of

maternally administered medications on the foetus.

It might also have led to a signifcant delay in

instituting treatment. The CT scan ruled out

trauma and intracranial haemorrhage as the causes,

confrming the history of a seizure frst and then the

fall. Clinical and radiological fndings were more in

favour of PRES rather than superior sagittal sinus

thrombosis and subsequent MRI confrmed resolution

of the pathology.

We opted in favour of induction of labour and

vaginal delivery for the following reasons: the patient

did not have intracranial haemorrhage and showed

rapid neurological improvement; this avoided the

short- and long-term maternal risks of caesarean

delivery

10

and the neonatal outcome was not expected

to be favourable (preterm with severe intrauterine

growth retardation).

The main signifcance of this report lies in the

antepartum presentation of PRES. Antepartum

PRES poses different challenges to PRES in non-

obstetric or postpartum patients because of the

additional management aspects to ensure foetal

wellbeing. We were posed with a diffcult decision

when balancing the disadvantages of caesarean

section versus the risks of vaginal delivery and the

rapid neurological improvement of the patient

infuenced our decision. This case supports others

in suggesting that the outcome for obstetric patients

with PRES is favourable and that timely supportive

therapy is the single most important aspect of

management. Magnesium sulphate was effective

in stabilising this patient. Labour pain might have

contributed to the slightly higher than recommended

blood pressure because we did not provide analgesia

during labour, other than fentanyl at admission to

the surgical intensive care unit. In addition, an

infusion of labetalol (rather than the intermittent

dosing) would probably have avoided fuctuations in

blood pressure.

Although PRES was frst described in 1996

17

and

is considered a rare clinical syndrome, a single

search term of posterior reversible encephalopathy

syndrome yielded nearly 450 articles in PubMed,

with more than 200 articles (mostly case reports and

a few case series) published in the last two years.

This indicates increased awareness about PRES

among clinicians and the impact of widespread

availability of imaging modalities like CT and MRI.

One obstetric textbook states that the radiological

and clinical features of PRES are almost universally

present in eclamptic patients

10

. This questions

whether PRES should still be considered a rare

syndrome, especially amongst obstetric patients,

502

H. V. HEGDE, P. B. PATIL ET AL

Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Vol. 39, No. 3, May 2011

and whether all eclamptic patients should undergo

neuroimaging. A study of PRES in severe pre-

eclampsia and eclampsia may help. Early recognition

of PRES is important for timely institution of

therapy, which typically consists of gradual blood

pressure control and removal or management of

precipitating factors.

REFERENCES

1. Servillo G, Striano P, Striano S, Tortora F, Boccella P, De

Robertis E et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

(PRES) in critically ill obstetric patients. Intensive Care Med

2003; 29:2323-2326.

2. Powell ES, Goldman MJ. Posterior reversible encephalopathy

syndrome (PRES) in a thirty-six-week gestation eclamptic. J

Emerg Med 2007; 33:377-379.

3. Gasco J, Rangel-Castilla L, Clark S, Franklin B,

Satchithanandam L, Salinas P. Hemorrhagic stroke with intra-

ventricular extension in the setting of acute posterior reversible

encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): case report. Neurocirugia

(Astur) 2009; 20:57-61.

4. Morelli N, Gori S, Michelassi MC, Falorni M, Cafforio G,

Bianchi MC et al. Atypical posterior reversible encephalopathy

syndrome in puerperium. Eur Neurol 2008; 59:195-197.

5. Brownfoot FC, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Different corticos-

teroids and regimens for accelerating fetal lung maturation for

women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2008; 4:CD006764.

6. Lee VH, Wijdicks EF, Manno EM, Rabinstein AA. Clinical

spectrum of reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syn-

drome. Arch Neurol 2008; 65:205-210.

7. Eran A, Barak M. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syn-

drome after combined general and spinal anesthesia with

intrathecal morphine. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:609-612.

8. Ortiz GA, Bianchi NA, Tiede MP, Bhatia RG. Posterior revers-

ible encephalopathy syndrome after intravenous caffeine for

post-lumbar puncture headaches. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol

2009; 30:586-587.

9. Aranas RM, Prabhakaran S, Lee VH. Posterior reversi-

ble encephalopathy syndrome associated with hemorrhage.

Neurocrit Care 2009; 10:306-312.

10. Pregnancy Hypertension. In: Cunningham FG, ed. Williams

Obstetrics, 23rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill 2010. p. 706-

756.

11. Witlin AG, Friedman SA, Egerman RS, Frangieh AY, Sibai

BM. Cerebrovascular disorders complicating pregnancy

beyond eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 176:1139-1148.

12. Fugate JE, Claassen DO, Cloft HJ, Kallmes DF, Kozak OS,

Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome:

associated clinical and radiologic findings. Mayo Clin Proc

2010; 85:427-432.

13. Moratalla MB. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Emerg Med J 2010; 27: 547.

14. Stott VL, Hurrell MA, Anderson TJ. Reversible posterior

leukoencephalopathy syndrome: a misnomer reviewed. Intern

Med J 2005; 35:83-90.

15. Casey SO, Sampaio RC, Michel E, Truwit CL. Posterior

reversible encephalopathy syndrome: utility of fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery MR imaging in the detection of cortical and

subcortical lesions. Am J Neuroradiol 2000; 21:1199-1206.

16. Covarrubias DJ, Luetmer PH, Campeau NG. Posterior revers-

ible encephalopathy syndrome: prognostic utility of quantita-

tive diffusion-weighted MR images. Am J Neuroradiol 2002;

23:1038-1048.

17. Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A et

al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N

Engl J Med 1996; 334:494-500.

Copyright of Anaesthesia & Intensive Care is the property of Australian Society of Anaesthetists and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- 4810cr10 PDFDocument2 pages4810cr10 PDFdr.putra888No ratings yet

- Spontaneous Haemorrhagic Stroke Complicating Severe Pre-Eclampsia in Pregnancy: A Case Report in A Resource-Limited Setting in CameroonDocument4 pagesSpontaneous Haemorrhagic Stroke Complicating Severe Pre-Eclampsia in Pregnancy: A Case Report in A Resource-Limited Setting in CameroonDewina Dyani RosariNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Eclampsia PDFDocument2 pagesPostpartum Eclampsia PDFMo Fadra0% (1)

- Late Postpartum EclampsiaDocument4 pagesLate Postpartum Eclampsiaapi-3702092No ratings yet

- Pentalogy of Fallot Review NotesDocument11 pagesPentalogy of Fallot Review NotesMutivanya Inez MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Hydatidiform Mole With Hyperthyroidism - Perioperative ChallengesDocument2 pagesHydatidiform Mole With Hyperthyroidism - Perioperative ChallengesAl MubartaNo ratings yet

- A Severe Asphyxiated Newborn: A Case ReportDocument13 pagesA Severe Asphyxiated Newborn: A Case ReportEeeeeeeeeNo ratings yet

- BJOG P 380Document2 pagesBJOG P 380Amanqui Alex DerlyNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Management of A Child With A Positive Family History of Malignant Hyperthermia For Posterior Fossa Surgery in The Sitting PositionDocument3 pagesAnaesthetic Management of A Child With A Positive Family History of Malignant Hyperthermia For Posterior Fossa Surgery in The Sitting PositionkrishNo ratings yet

- Transient Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Following Propofol and Fentanyl Administration in A Healthy 19-Year-Old PatientDocument2 pagesTransient Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Following Propofol and Fentanyl Administration in A Healthy 19-Year-Old PatientAchmad Ageng SeloNo ratings yet

- Atyp EclmDocument6 pagesAtyp Eclmzamurd76No ratings yet

- Medicine: Sudden Seizure During Cesarean SectionDocument2 pagesMedicine: Sudden Seizure During Cesarean SectionDavid RefuncionNo ratings yet

- Peripartum Care of The Parturient With Acute Fatty Liver of PregnancyDocument3 pagesPeripartum Care of The Parturient With Acute Fatty Liver of PregnancyDebNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH) : Case Scenario 4Document4 pagesPregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH) : Case Scenario 4Mae Arra Lecobu-anNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrest in Pregnancy and Perimortem Cesarean Delivery CaseDocument5 pagesCardiac Arrest in Pregnancy and Perimortem Cesarean Delivery CaseYoomiif BedadaNo ratings yet

- MefenamicDocument9 pagesMefenamicmisslhenNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Caesarean Section in A Patient With Eisenmenger's SyndromeDocument3 pagesAnaesthesia For Caesarean Section in A Patient With Eisenmenger's SyndromeRasyid DorkzNo ratings yet

- J Jclinane 2005 08 012Document3 pagesJ Jclinane 2005 08 012Novi Yanti NyNo ratings yet

- 2015 319 TJOG RefractoryVTinpregnancyDocument3 pages2015 319 TJOG RefractoryVTinpregnancyIsmul 'D' SadlyNo ratings yet

- Uterine Rupture in A Primigravid Patient and Anesthetic Implications: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesUterine Rupture in A Primigravid Patient and Anesthetic Implications: A Case ReportYahia AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pregnant Patient With Eclampsia For Emergency Cesarean Section Case FileDocument2 pagesPregnant Patient With Eclampsia For Emergency Cesarean Section Case Filehttps://medical-phd.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- The Use of Plasma Exchange in A Very Earlyonset and Life Threatening Hemolysis Elevated Liver Enzymes and Low Platelet Hellp Syndr 2161 0932 1000387Document4 pagesThe Use of Plasma Exchange in A Very Earlyonset and Life Threatening Hemolysis Elevated Liver Enzymes and Low Platelet Hellp Syndr 2161 0932 1000387Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy: A Case ReportDocument0 pagesAcute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy: A Case ReportnajmulNo ratings yet

- Thalssemia & Spinal Cord Compression in PregnancyDocument1 pageThalssemia & Spinal Cord Compression in PregnancyThao NguyenNo ratings yet

- Severe Preeclampsia BahanDocument7 pagesSevere Preeclampsia BahanelenNo ratings yet

- Unas UnsriDocument29 pagesUnas UnsriMuhammad DasawarsaNo ratings yet

- Journal Hellp SyndromDocument3 pagesJournal Hellp SyndromElang SudewaNo ratings yet

- Yayie Case PresentationDocument12 pagesYayie Case PresentationYayie Querubin SilvestreNo ratings yet

- West Avenue, Molo, Iloilo City NCM 109 Rle: Care of Mother, Child at Risk or With Problems (Acute and Chronic)Document3 pagesWest Avenue, Molo, Iloilo City NCM 109 Rle: Care of Mother, Child at Risk or With Problems (Acute and Chronic)snow.parconNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Pediatric CareDocument4 pagesCase Study of Pediatric CareazafatimatuzzahraNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Scientific Research: AnesthesiologyDocument2 pagesInternational Journal of Scientific Research: AnesthesiologyALfuNo ratings yet

- Severe Erythroderma As A Complication of Continuous Epoprostenol TherapyDocument3 pagesSevere Erythroderma As A Complication of Continuous Epoprostenol Therapy568563No ratings yet

- Takayasu's Artheritis During PregnancyDocument11 pagesTakayasu's Artheritis During PregnancyAgung Sunarko PutraNo ratings yet

- Fernandez 1989Document2 pagesFernandez 1989Muhammad IqsanNo ratings yet

- Anestesi Pada GBSDocument4 pagesAnestesi Pada GBSyudhalantankNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument6 pagesCase ReportEka Budi UtamiNo ratings yet

- The Use of Levosimendan in Children With Cancer With Severe Acute Cardiac Dysfunction Case Series and A Review of The LiteratureDocument4 pagesThe Use of Levosimendan in Children With Cancer With Severe Acute Cardiac Dysfunction Case Series and A Review of The Literaturehadi40canadaNo ratings yet

- Management of Severe Postpartum Haemorrhage by Uterine Artery EmbolizationDocument4 pagesManagement of Severe Postpartum Haemorrhage by Uterine Artery EmbolizationAndi Tri SutrisnoNo ratings yet

- Persistent Paralysis After Spinal Paresthesia PDFDocument6 pagesPersistent Paralysis After Spinal Paresthesia PDFNadia Gina AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Kumari - Ephedrine Versus Phenylephrine Effects On Fetal Acid-Base Status During Spinal Anesthesia For Elective Cesarean DeliveryDocument5 pagesKumari - Ephedrine Versus Phenylephrine Effects On Fetal Acid-Base Status During Spinal Anesthesia For Elective Cesarean DeliveryFadil AhmadNo ratings yet

- An Extremely Rare and Life Threatening Thyrotoxicosis - FinalDocument12 pagesAn Extremely Rare and Life Threatening Thyrotoxicosis - FinalChristian PoerniawanNo ratings yet

- Trisomy 21 Fetus Co-Existent With A Partial Molar Pregnancy: Case ReportDocument2 pagesTrisomy 21 Fetus Co-Existent With A Partial Molar Pregnancy: Case ReportArga KafiNo ratings yet

- Approach To The PatientDocument11 pagesApproach To The PatientNaya FarmsiBthreendy X'iNo ratings yet

- Eclampsia: VI. Maternal-Perinatal Outcome in 254 Consecutive CasesDocument6 pagesEclampsia: VI. Maternal-Perinatal Outcome in 254 Consecutive CasesrizkaNo ratings yet

- Atypical EclampsiaDocument3 pagesAtypical EclampsiadianaristinugraheniNo ratings yet

- 631-Article Text-2378-1-10-20180830Document6 pages631-Article Text-2378-1-10-20180830azizhamoudNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Hemorrhage Post Placenta Previa Centralis-Conservative Management. Astrit M. GashiDocument4 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhage Post Placenta Previa Centralis-Conservative Management. Astrit M. GashiAstrit GashiNo ratings yet

- 4408 Case Report of Severe Preeclampsia and Associated Postpartum ComplicationsDocument3 pages4408 Case Report of Severe Preeclampsia and Associated Postpartum ComplicationsMesu MitchNo ratings yet

- Thoracic Epidural For Modified Radical Mastectomy in A High-Risk PatientDocument2 pagesThoracic Epidural For Modified Radical Mastectomy in A High-Risk PatientBianca CaterinalisendraNo ratings yet

- CPR PregnancyDocument25 pagesCPR PregnancyCutie PieNo ratings yet

- Cesarean Hysterectomy With Cystotomy in Parturient Having Placenta Percreta, Gestational Thrombocytopenia, and Portal Hypertension - A Case ReportDocument4 pagesCesarean Hysterectomy With Cystotomy in Parturient Having Placenta Percreta, Gestational Thrombocytopenia, and Portal Hypertension - A Case ReportasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2211419X13000578 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2211419X13000578 Mainindra040293No ratings yet

- Anes MNGMT Ped TraumaDocument5 pagesAnes MNGMT Ped Traumaramzi MohamedNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Splenic Rupture in A 21-Year Old Male Patient Patient: H.MDocument4 pagesSpontaneous Splenic Rupture in A 21-Year Old Male Patient Patient: H.MJoherNo ratings yet

- Sme PropofolDocument2 pagesSme PropofolAntonella Jazmín AssadNo ratings yet

- tmp2CD0 TMPDocument4 pagestmp2CD0 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Ondan Hipo 2Document6 pagesOndan Hipo 2putri maharani andesNo ratings yet

- 24 Fix PDFDocument4 pages24 Fix PDFmelvaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Caesarean Section in Patients With Uncontrolled HyperthyroidismDocument6 pagesAnaesthesia For Caesarean Section in Patients With Uncontrolled HyperthyroidismNut RonakritNo ratings yet

- Congenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandCongenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementDiva D. De León-CrutchlowNo ratings yet

- The Hypercoagulable State in Thalassemia: Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Clinical Trials and ObservationsDocument9 pagesThe Hypercoagulable State in Thalassemia: Hemostasis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology Clinical Trials and ObservationsNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident in B-Thalassemia Major (B-TM) and B-Thalassemia Intermedia (b-TI)Document3 pagesCerebrovascular Accident in B-Thalassemia Major (B-TM) and B-Thalassemia Intermedia (b-TI)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Cervical Stitch (Cerclage) For Preventing Pregnancy Loss: Individual Patient Data Meta-AnalysisDocument17 pagesCervical Stitch (Cerclage) For Preventing Pregnancy Loss: Individual Patient Data Meta-AnalysisNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Using Antimicrobial Surgihoney To Prevent Caesarean Wound InfectionDocument5 pagesUsing Antimicrobial Surgihoney To Prevent Caesarean Wound InfectionNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Do Clear Cell Ovarian Carcinomas Have Poorer Prognosis Compared To Other Epithelial Cell Types? A Study of 1411 Clear Cell Ovarian CancersDocument7 pagesDo Clear Cell Ovarian Carcinomas Have Poorer Prognosis Compared To Other Epithelial Cell Types? A Study of 1411 Clear Cell Ovarian CancersNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- The Role of Honey in The Management of Wounds: DiscussionDocument4 pagesThe Role of Honey in The Management of Wounds: DiscussionNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Distosia Ncbi (Ana)Document8 pagesDistosia Ncbi (Ana)Ni Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Title of The Presentation: Your SubtitleDocument2 pagesTitle of The Presentation: Your SubtitleNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Cytokeratin 7 and Cytokeratin 19 Expressions in Oval Cells and Mature Cholangiocytes As Diagnostic and Prognostic Factors of CholestasisDocument6 pagesCytokeratin 7 and Cytokeratin 19 Expressions in Oval Cells and Mature Cholangiocytes As Diagnostic and Prognostic Factors of CholestasisNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- CMV Primer Non PrimerDocument3 pagesCMV Primer Non PrimerNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Pendapat Holy GrailDocument4 pagesPendapat Holy GrailNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Insertion of An Intrauterine Contraceptive Device After Induced or Spontaneous Abortion: A Review of The EvidenceDocument6 pagesInsertion of An Intrauterine Contraceptive Device After Induced or Spontaneous Abortion: A Review of The EvidenceNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Human Rabies: Neuropathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management: ReviewDocument16 pagesHuman Rabies: Neuropathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management: ReviewNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Uterine StimulantsDocument24 pagesUterine StimulantsKilp MosesNo ratings yet

- Maternal Health: Ekta Modi 2 MPT in RehabDocument368 pagesMaternal Health: Ekta Modi 2 MPT in RehabMihir_Mehta_5497100% (1)

- Induction of Labour For Post MaturityDocument6 pagesInduction of Labour For Post MaturityYwagar YwagarNo ratings yet

- Labor and Delivery ComplicationsDocument50 pagesLabor and Delivery ComplicationskjayjocsinNo ratings yet

- Complications With The Passenger 2Document77 pagesComplications With The Passenger 2JudyNo ratings yet

- 1-Drugs Affecting Uterine Muscle ContractilityDocument40 pages1-Drugs Affecting Uterine Muscle ContractilityjojolilimomoNo ratings yet

- High - Risk Labor and Delivery 2Document106 pagesHigh - Risk Labor and Delivery 2Charmaine Louie Macalanda Lopez-Soriano100% (2)

- Get Through MRCOG Part 1 2nd EditionDocument142 pagesGet Through MRCOG Part 1 2nd Editionmustafa benmuhsen50% (2)

- 2-Post TermDocument13 pages2-Post TermAbc DefNo ratings yet

- Induction and Augmentation of LabourDocument73 pagesInduction and Augmentation of LabourSanthosh.S.U100% (4)

- Preterm and Posterm Birth: Oleh: DR Adi Setyawan Prianto SP - OG (K)Document31 pagesPreterm and Posterm Birth: Oleh: DR Adi Setyawan Prianto SP - OG (K)ATIKAH NUR HAFIZHAHNo ratings yet

- Management For PROMDocument2 pagesManagement For PROMSajaratul Syifaa'No ratings yet

- MU-MCQs (2020) OBS & GYNDocument330 pagesMU-MCQs (2020) OBS & GYNGhaiidaa khh100% (1)

- Safe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGDocument16 pagesSafe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGAryaNo ratings yet

- Augmentation of LabourDocument45 pagesAugmentation of LabourLamnunnem HaokipNo ratings yet

- Robsons Ten Group Classification of Cesarean Section at A Tertiary Center in NepalDocument6 pagesRobsons Ten Group Classification of Cesarean Section at A Tertiary Center in NepalgehanathNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorders in PregnancyDocument96 pagesHypertensive Disorders in PregnancySalman Habeeb100% (4)

- Progression of First Stage LaourDocument14 pagesProgression of First Stage LaourAlmira Dyah PuspitariniNo ratings yet

- (PBL) Induction of Labor and Bishop's ScoreDocument10 pages(PBL) Induction of Labor and Bishop's ScoreSean WangNo ratings yet

- Rekap Inap Obsetetri PerdiagnosaDocument142 pagesRekap Inap Obsetetri Perdiagnosafatha_87No ratings yet

- Hypnosis Antenatal Training For Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesHypnosis Antenatal Training For Childbirth: A Randomised Controlled TrialEka AfriliaNo ratings yet

- Katharine GravesDocument34 pagesKatharine GravesDanaNo ratings yet

- Update On Uterine Tachysystolehobson2018Document9 pagesUpdate On Uterine Tachysystolehobson2018Raul A UrbinaNo ratings yet

- Labour Interventions ReportDocument20 pagesLabour Interventions Reportdwi handayaniNo ratings yet

- Mcqs Test Unit 8 With KeyDocument5 pagesMcqs Test Unit 8 With Keyyasodha maharajNo ratings yet

- Premature Rupture of MembranesDocument10 pagesPremature Rupture of Membranessami samiNo ratings yet

- Easier Shorter Safer BirthDocument53 pagesEasier Shorter Safer Birthmw101mw100% (1)

- ObstetricsDocument216 pagesObstetricsሌናፍ ኡሉምNo ratings yet

- Edit - HIL - Daily IGD 25.09.19Document30 pagesEdit - HIL - Daily IGD 25.09.19Inez WijayaNo ratings yet

- Nur 2310 Maternal Exam Questions and AnswersDocument80 pagesNur 2310 Maternal Exam Questions and AnswersNelson MandelaNo ratings yet