Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crimpro 2nd Set Cases

Uploaded by

Rotciv Reyes Cumigad0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views53 pagesjudge palamos assigned cases

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentjudge palamos assigned cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views53 pagesCrimpro 2nd Set Cases

Uploaded by

Rotciv Reyes Cumigadjudge palamos assigned cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 53

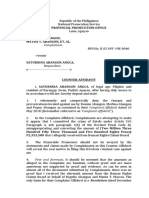

SECOND DIVISION

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES,

Petitioner,

- versus -

MA. THERESA PANGILINAN,

Respondent.

G.R. No. 152662

Present:

CARPIO,

Chairperson,

BRION,

PEREZ,

SERENO, and

REYES, JJ.

Promulgated:

June 13, 2012

x - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x

DECISION

PEREZ, J.:

The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) filed this petition for

certiorari1[1] under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, on behalf of the Republic

of the Philippines, praying for the nullification and setting aside of the

Decision2[2] of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP No. 66936,

entitled Ma. Theresa Pangilinan vs. People of the Philippines and Private

Complainant Virginia C. Malolos.

The fallo of the assailed Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is GRANTED.

Accordingly, the assailed Decision of the Regional Trial Court of

Quezon City, Branch 218, is REVERSED and SET ASIDE and

Criminal Cases Nos. 89152 and 89153 against petitioner Ma.

Theresa Pangilinan are hereby ordered DISMISSED.3[3]

1[1] Rollo, pp. 33-66.

2[2] Penned by Associate Justice Perlita J. Tria Tirona with Associate Justices Eubulo G.

Verzola and Bernardo P. Abesamis, concurring. CA rollo, pp. 162-170.

3[3] Id. at 169.

Culled from the record are the following undisputed facts:

On 16 September 1997, Virginia C. Malolos (private complainant)

filed an affidavit-complaint for estafa and violation of Batas Pambansa (BP)

Blg. 22 against Ma. Theresa Pangilinan (respondent) with the Office of the

City Prosecutor of Quezon City. The complaint alleges that respondent

issued nine (9) checks with an aggregate amount of Nine Million Six

Hundred Fifty-Eight Thousand Five Hundred Ninety-Two Pesos

(P9,658,592.00) in favor of private complainant which were dishonored

upon presentment for payment.

On 5 December 1997, respondent filed a civil case for accounting,

recovery of commercial documents, enforceability and effectivity of

contract and specific performance against private complainant before the

Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Valenzuela City. This was docketed as Civil

Case No. 1429-V-97.

Five days thereafter or on 10 December 1997, respondent filed a

Petition to Suspend Proceedings on the Ground of Prejudicial Question

before the Office of the City Prosecutor of Quezon City, citing as basis the

pendency of the civil action she filed with the RTC of Valenzuela City.

On 2 March 1998, Assistant City Prosecutor Ruben Catubay

recommended the suspension of the criminal proceedings pending the

outcome of the civil action respondent filed against private complainant

with the RTC of Valenzuela City. The recommendation was approved by

the City Prosecutor of Quezon City.

Aggrieved, private complainant raised the matter before the

Department of Justice (DOJ).

On 5 January 1999, then Secretary of Justice Serafin P. Cuevas

reversed the resolution of the City Prosecutor of Quezon City and ordered

the filing of informations for violation of BP Blg. 22 against respondent in

connection with her issuance of City Trust Check No. 127219 in the amount

of P4,129,400.00 and RCBC Check No. 423773 in the amount of

P4,475,000.00, both checks totaling the amount of P8,604,000.00. The estafa

and violation of BP Blg. 22 charges involving the seven other checks

included in the affidavit-complaint filed on 16 September 1997 were,

however, dismissed.

Consequently, two counts for violation of BP Blg. 22, both dated 18

November 1999, were filed against respondent Ma.Theresa Pangilinan on 3

February 2000 before the Office of the Clerk of Court, Metropolitan Trial

Court (MeTC), Quezon City. These cases were raffled to MeTC, Branch

31on 7 June 2000.

On 17 June 2000, respondent filed an Omnibus Motion to Quash the

Information and to Defer the Issuance of Warrant of Arrest before MeTC,

Branch 31, Quezon City. She alleged that her criminal liability has been

extinguished by reason of prescription.

The presiding judge of MeTC, Branch 31, Quezon City granted the

motion in an Order dated 5 October 2000.

On 26 October 2000, private complainant filed a notice of appeal. The

criminal cases were raffled to RTC, Branch 218, Quezon City.

In a Decision dated 27 July 2001, the presiding judge of RTC, Branch

218, Quezon City reversed the 5 October 2000 Order of the MeTC. The

pertinent portion of the decision reads:

xxx Inasmuch as the informations in this case were filed

on 03 February 2000 with the Clerk of Court although received

by the Court itself only on 07 June 2000, they are covered by the

Rule as it was worded before the latest amendment. The

criminal action on two counts for violation of BP Blg. 22, had,

therefore, not yet prescribed when the same was filed with the

court a quo considering the appropriate complaint that started

the proceedings having been filed with the Office of the

Prosecutor on 16 September 1997 yet.

WHEREFORE, the assailed Order dated 05 October 2000 is

hereby REVERSED AND SET ASIDE. The Court a quo is hereby

directed to proceed with the hearing of Criminal Cases Nos.

89152 and 89153.4[4]

Dissatisfied with the RTC Decision, respondent filed with the

Supreme Court a petition for review5[5] on certiorari under Rule 45 of the

Rules of Court. This was docketed as G.R. Nos. 149486-87.

4[4] Rollo, p. 133.

5[5] Id. at 134-167.

In a resolution6[6] dated 24 September 2000, this Court referred the

petition to the CA for appropriate action.

On 26 October 2001, the CA gave due course to the petition by

requiring respondent and private complainant to comment on the petition.

In a Decision dated 12 March 2002, the CA reversed the 27 July 2001

Decision of RTC, Branch 218, Quezon City, thereby dismissing Criminal

Case Nos. 89152 and 89153 for the reason that the cases for violation of BP

Blg. 22 had already prescribed.

In reversing the RTC Decision, the appellate court ratiocinated that:

xxx this Court reckons the commencement of the period of

prescription for violations of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 imputed to

[respondent] sometime in the latter part of 1995, as it was within

this period that the [respondent] was notified by the private

[complainant] of the fact of dishonor of the subject checks and, the

five (5) days grace period granted by law had elapsed. The

private respondent then had, pursuant to Section 1 of Act 3326, as

amended, four years therefrom or until the latter part of 1999 to

6[6] Id. at 169.

file her complaint or information against the petitioner before the

proper court.

The informations docketed as Criminal Cases Nos. 89152

and 89152(sic) against the petitioner having been filed with the

Metropolitan Trial Court of Quezon City only on 03 February

2000, the said cases had therefore, clearly prescribed.

xxx

Pursuant to Section 2 of Act 3326, as amended, prescription

shall be interrupted when proceedings are instituted against the

guilty person.

In the case of Zaldivia vs. Reyes7[7] the Supreme Court

held that the proceedings referred to in Section 2 of Act No. 3326,

as amended, are judicial proceedings, which means the filing of

the complaint or information with the proper court. Otherwise

stated, the running of the prescriptive period shall be stayed on

the date the case is actually filed in court and not on any date

before that, which is in consonance with Section 2 of Act 3326, as

amended.

While the aforesaid case involved a violation of a

municipal ordinance, this Court, considering that Section 2 of Act

3326, as amended, governs the computation of the prescriptive

period of both ordinances and special laws, finds that the ruling

of the Supreme Court in Zaldivia v. Reyes8[8] likewise applies to

special laws, such as Batas Pambansa Blg. 22.9[9]

7[7] G.R. No. 102342, 3 July 1992, 211 SCRA 277.

8[8] Id.

9[9] CA rollo, pp. 167-168.

The OSG sought relief to this Court in the instant petition for review.

According to the OSG, while it admits that Act No. 3326, as amended by

Act No. 3585 and further amended by Act No. 3763 dated 23 November

1930, governs the period of prescription for violations of special laws, it is

the institution of criminal actions, whether filed with the court or with the

Office of the City Prosecutor, that interrupts the period of prescription of

the offense charged.10[10] It submits that the filing of the complaint-

affidavit by private complainant Virginia C. Malolos on 16 September 1997

with the Office of the City Prosecutor of Quezon City effectively

interrupted the running of the prescriptive period of the subject BP Blg. 22

cases.

Petitioner further submits that the CA erred in its decision when it

relied on the doctrine laid down by this Court in the case of Zaldivia v.

Reyes, Jr.11[11] that the filing of the complaint with the Office of the City

Prosecutor is not the judicial proceeding that could have interrupted the

period of prescription. In relying on Zaldivia,12[12] the CA allegedly failed

to consider the subsequent jurisprudence superseding the aforesaid ruling.

10[10] Section 1, Rule 110 of the 1997 Rules of Criminal Procedure

11[11] Supra note 7 at 284-285.

12[12] Supra.

Petitioner contends that in a catena of cases,13[13] the Supreme Court

ruled that the filing of a complaint with the Fiscals Office for preliminary

investigation suspends the running of the prescriptive period. It therefore

concluded that the filing of the informations with the MeTC of Quezon

City on 3 February 2000 was still within the allowable period of four years

within which to file the criminal cases for violation of BP Blg. 22 in

accordance with Act No. 3326, as amended.

In her comment-opposition dated 26 July 2002, respondent avers that

the petition of the OSG should be dismissed outright for its failure to

comply with the mandatory requirements on the submission of a certified

true copy of the decision of the CA and the required proof of service. Such

procedural lapses are allegedly fatal to the cause of the petitioner.

Respondent reiterates the ruling of the CA that the filing of the

complaint before the City Prosecutors Office did not interrupt the running

of the prescriptive period considering that the offense charged is a

violation of a special law.

13[13] Calderon-Bargas v. RTC of Pasig, Metro Manila, Br. 162, G.R. Nos. 103259-61, 1

October 1993, 227 SCRA 56; Francisco v. CA, G.R. No. L-45674, 30 May 1983, 122 SCRA

538; Ingco v. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 112584, 23 May 1997, 272 SCRA 563.

Respondent contends that the arguments advanced by petitioner are

anchored on erroneous premises. She claims that the cases relied upon by

petitioner involved felonies punishable under the Revised Penal Code and

are therefore covered by Article 91 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC)14[14]

and Section 1, Rule 110 of the Revised Rules on Criminal Procedure.15[15]

Respondent pointed out that the crime imputed against her is for violation

of BP Blg. 22, which is indisputably a special law and as such, is governed

by Act No. 3326, as amended. She submits that a distinction should thus

be made between offenses covered by municipal ordinances or special

laws, as in this case, and offenses covered by the RPC.

The key issue raised in this petition is whether the filing of the

affidavit-complaint for estafa and violation of BP Blg. 22 against

14[14] Article 91. Computation of prescription of offenses. The period of prescription shall commence

to run from the day on which the crime is discovered by the offended party, the authorities, or their

agents, and shall be interrupted by the filing of the complaint or information, and shall commence to run

again when such proceedings terminate without the accused being convicted or acquitted, or are unjustifiably

stopped for any reason not imputable to him.

The term of prescription shall not run when the offender is absent from the Philippine Archipelago.

15[15] Section 1. Institution of criminal actions.Criminal actions shall be instituted as follows:

xxx

xxx

The institution of the criminal action shall interrupt the running of the period of

prescription of the offense charged unless otherwise provided in special laws.

respondent with the Office of the City Prosecutor of Quezon City on 16

September 1997 interrupted the period of prescription of such offense.

We find merit in this petition.

Initially, we see that the respondents claim that the OSG failed to

attach to the petition a duplicate original or certified true copy of the 12

March 2002 decision of the CA and the required proof of service is refuted

by the record. A perusal of the record reveals that attached to the original

copy of the petition is a certified true copy of the CA decision. It was also

observed that annexed to the petition was the proof of service undertaken

by the Docket Division of the OSG.

With regard to the main issue of the petition, we find that the CA

reversively erred in ruling that the offense committed by respondent had

already prescribed. Indeed, Act No. 3326 entitled An Act to Establish

Prescription for Violations of Special Acts and Municipal Ordinances and

to Provide When Prescription Shall Begin, as amended, is the law

applicable to BP Blg. 22 cases. Appositely, the law reads:

SECTION 1. Violations penalized by special acts shall,

unless otherwise provided in such acts, prescribe in accordance

with the following rules: (a) xxx; (b) after four years for those

punished by imprisonment for more than one month, but less

than two years; (c) xxx.

SECTION 2. Prescription shall begin to run from the day

of the commission of the violation of the law, and if the same be

not known at the time, from the discovery thereof and the

institution of judicial proceedings for its investigation and

punishment.

The prescription shall be interrupted when proceedings

are instituted against the guilty person, and shall begin to run

again if the proceedings are dismissed for reasons not

constituting jeopardy.

Since BP Blg. 22 is a special law that imposes a penalty of

imprisonment of not less than thirty (30) days but not more than one year

or by a fine for its violation, it therefor prescribes in four (4) years in

accordance with the aforecited law. The running of the prescriptive period,

however, should be tolled upon the institution of proceedings against the

guilty person.

In the old but oft-cited case of People v. Olarte,16[16] this Court ruled

that the filing of the complaint in the Municipal Court even if it be merely

for purposes of preliminary examination or investigation, should, and thus,

interrupt the period of prescription of the criminal responsibility, even if

16[16] G.R. No. L-22465, 28 February 1967, 19 SCRA 494, 500.

the court where the complaint or information is filed cannot try the case on

the merits. This ruling was broadened by the Court in the case of

Francisco, et.al. v. Court of Appeals, et. al.17[17] when it held that the filing of

the complaint with the Fiscals Office also suspends the running of the

prescriptive period of a criminal offense.

Respondents contention that a different rule should be applied to

cases involving special laws is bereft of merit. There is no more distinction

between cases under the RPC and those covered by special laws with

respect to the interruption of the period of prescription. The ruling in

Zaldivia v. Reyes, Jr.18[18] is not controlling in special laws. In Llenes v.

Dicdican,19[19] Ingco, et al. v. Sandiganbayan,20[20] Brillante v. CA,21[21] and

Sanrio Company Limited v. Lim,22[22] cases involving special laws, this

Court held that the institution of proceedings for preliminary investigation

against the accused interrupts the period of prescription. In Securities and

Exchange Commission v. Interport Resources Corporation, et. al.,23[23] the

17[17] 207 Phil 471, 477 (1983).

18[18] Supra note 7.

19[19] 328 Phil. 1272 (1996).

20[20] Supra note 13.

21[21] 483 Phil. 568 (2004)

22[22] G.R. No. 168662, 19 February 2008, 546 SCRA 303.

23[23] G.R. No. 135808, 6 October 2008, 567 SCRA 354, 415-416.

Court even ruled that investigations conducted by the Securities and

Exchange Commission for violations of the Revised Securities Act and the

Securities Regulations Code effectively interrupts the prescription period

because it is equivalent to the preliminary investigation conducted by the

DOJ in criminal cases.

In fact, in the case of Panaguiton, Jr. v. Department of Justice,24[24]

which is in all fours with the instant case, this Court categorically ruled

that commencement of the proceedings for the prosecution of the accused

before the Office of the City Prosecutor effectively interrupted the

prescriptive period for the offenses they had been charged under BP Blg.

22. Aggrieved parties, especially those who do not sleep on their rights

and actively pursue their causes, should not be allowed to suffer

unnecessarily further simply because of circumstances beyond their

control, like the accuseds delaying tactics or the delay and inefficiency of

the investigating agencies.

We follow the factual finding of the CA that sometime in the latter

part of 1995 is the reckoning date of the commencement of presumption

for violations of BP Blg. 22, such being the period within which herein

24[24] G.R. No. 167571, 25 November 2008, 571 SCRA 549, 562.

respondent was notified by private complainant of the fact of dishonor of

the checks and the five-day grace period granted by law elapsed.

The affidavit-complaints for the violations were filed against

respondent on 16 September 1997. The cases reached the MeTC of Quezon

City only on 13 February 2000 because in the meanwhile, respondent filed

a civil case for accounting followed by a petition before the City Prosecutor

for suspension of proceedings on the ground of prejudicial question. The

matter was raised before the Secretary of Justice after the City Prosecutor

approved the petition to suspend proceedings. It was only after the

Secretary of Justice so ordered that the informations for the violation of BP

Blg. 22 were filed with the MeTC of Quezon City.

Clearly, it was respondents own motion for the suspension of the

criminal proceedings, which motion she predicated on her civil case for

accounting, that caused the filing in court of the 1997 initiated proceedings

only in 2000.

As laid down in Olarte,25[25] it is unjust to deprive the injured party of

the right to obtain vindication on account of delays that are not under his

25[25] Supra note 16.

control. The only thing the offended must do to initiate the prosecution of

the offender is to file the requisite complaint.

IN LIGHT OF ALL THE FOREGOING, the instant petition is

GRANTED. The 12 March 2002 Decision of the Court of Appeals is

hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The Department of Justice is

ORDERED to re-file the informations for violation of BP Blg. 22 against the

respondent.

SO ORDERED.

JOSE PORTUGAL PEREZ

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Senior Associate Justice

Chairperson

ARTURO D. BRION MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO

Associate Justice Associate Justice

BIENVENIDO L. REYES

Associate Justice

CERTIFICATION

I certify that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached

in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of

the Courts Division.

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Senior Associate Justice

(Per Section 12, R.A. 296,

The Judiciary Act of 1948, as

amended)

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. 102342 July 3, 1992

LUZ M. ZALDIVIA, petitioner,

vs.

HON. ANDRES B. REYES, JR., in his capacity as Acting Presiding Judge

of the Regional Trial Court, Fourth Judicial Region, Branch 76, San

Mateo, Rizal, and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents.

CRUZ, J.:

The Court is asked to determine the applicable law specifying the

prescriptive period for violations of municipal ordinances.

The petitioner is charged with quarrying for commercial purposes without

a mayor's permit in violation of Ordinance No. 2, Series of 1988, of the

Municipality of Rodriguez, in the Province of Rizal.

The offense was allegedly committed on May 11, 1990.

1

The referral-

complaint of the police was received by the Office of the Provincial

Prosecutor of Rizal on May 30, 1990.

2

The corresponding information was

filed with the Municipal Trial Court of Rodriguez on October 2, 1990.

3

The petitioner moved to quash the information on the ground that the

crime had prescribed, but the motion was denied. On appeal to the

Regional Trial Court of Rizal, the denial was sustained by the respondent

judge.

4

In the present petition for review on certiorari, the petitioner first argues

that the charge against her is governed by the following provisions of the

Rule on Summary Procedure:

Sec. 1. Scope This rule shall govern the procedure in the

Metropolitan Trial Courts, the Municipal Trial Courts, and the

Municipal Circuit Trial Courts in the following cases:

xxx xxx xxx

B. Criminal Cases:

1. Violations of traffic laws, rules and regulations;

2. Violations of rental law;

3. Violations of municipal or city ordinances;

4. All other criminal cases where the penalty prescribed by law for the

offenses charged does not exceed six months imprisonment, or a fine of

one thousand pesos (P1,000.00), or both, irrespective of other

imposable penalties, accessory or otherwise, or of the civil liability

arising therefrom. . . . (Emphasis supplied.)

xxx xxx xxx

Sec. 9. How commenced. The prosecution of criminal cases

falling within the scope of this Rule shall be either by complaint

or by information filed directly in court without need of a prior

preliminary examination or preliminary investigation:

Provided, however, That in Metropolitan Manila and chartered

cities, such cases shall be commenced only by information;

Provided, further, That when the offense cannot be prosecuted

de oficio, the corresponding complaint shall be signed and

sworn to before the fiscal by the offended party.

She then invokes Act. No. 3326, as amended, entitled "An Act to Establish

Periods of Prescription for Violations Penalized by Special Acts and

Municipal Ordinances and to Provide When Prescription Shall Begin to

Run," reading as follows:

Sec. 1. Violations penalized by special acts shall, unless

provided in such acts, prescribe in accordance with the

following rules: . . . Violations penalized by municipal ordinances

shall prescribe after two months.

Sec. 2. Prescription shall begin to run from the day of the

commission of the violation of the law, and if the same be not

known at the time, from the discovery thereof and the

institution of judicial proceedings for its investigation and

punishment.

The prescription shall be interrupted when proceedings are instituted

against the guilty person, and shall begin to run again if the

proceedings are dismissed for reasons not constituting jeopardy.

Sec. 3. For the purposes of this Act, special acts shall be acts

defining and penalizing violations of law not included in the

Penal Code. (Emphasis supplied)

Her conclusion is that as the information was filed way beyond the

two-month statutory period from the date of the alleged commission of the

offense, the charge against her should have been dismissed on the ground

of prescription.

For its part, the prosecution contends that the prescriptive period was

suspended upon the filing of the complaint against her with the Office of

the Provincial Prosecutor. Agreeing with the respondent judge, the

Solicitor General also invokes Section 1, Rule 110 of the 1985 Rules on

Criminal Procedure, providing as follows:

Sec. 1. How Instituted For offenses not subject to the rule on

summary procedure in special cases, the institution of criminal

action shall be as follows:

a) For offenses falling under the jurisdiction of the

Regional Trial Court, by filing the complaint with

the appropriate officer for the purpose of

conducting the requisite preliminary investigation

therein;

b) For offenses falling under the jurisdiction of the

Municipal Trial Courts and Municipal Circuit Trial

Courts, by filing the complaint directly with the

said courts, or a complaint with the fiscal's office.

However, in Metropolitan Manila and other

chartered cities, the complaint may be filed only

with the office of the fiscal.

In all cases such institution interrupts the period of prescription of the

offense charged. (Emphasis supplied.)

Emphasis is laid on the last paragraph. The respondent maintains that the

filing of the complaint with the Office of the Provincial Prosecutor comes

under the phrase "such institution" and that the phrase "in all cases" applies

to all cases, without distinction, including those falling under the Rule on

Summary Procedure.

The said paragraph, according to the respondent, was an adoption of the

following dictum in Francisco v. Court of Appeals:

5

In view of this diversity of precedents, and in order to provide

guidance for Bench and Bar, this Court has re-examined the

question and, after mature consideration, has arrived at the

conclusion that the true doctrine is, and should be, the one

established by the decisions holding that the filing of the

complaint in the Municipal Court, even if it be merely for

purposes of preliminary examination or investigation, should,

and does, interrupt the period of prescription of the criminal

responsibility, even if the court where the complaint or

information is filed can not try the case on its merits. Several

reasons buttress this conclusion: first, the text of Article 91 of

the Revised Penal Code, in declaring that the period of

prescription "shall be interrupted by the filing of the complaint

or information" without distinguishing whether the complaint

is filed in the court for preliminary examination or investigation

merely, or for action on the merits. Second, even if the court

where the complaint or information is filed may only proceed

to investigate the case, its actuations already represent the

initial step of the proceedings against the offender. Third, it is

unjust to deprive the injured party of the right to obtain

vindication on account of delays that are not under his control.

All that the victim of the offense may do on his part to initiate

the prosecution is to file the requisite complaint.

It is important to note that this decision was promulgated on May 30, 1983,

two months before the promulgation of the Rule on Summary Procedure

on August 1, 1983. On the other hand, Section 1 of Rule 110 is new, having

been incorporated therein with the revision of the Rules on Criminal

Procedure on January 1, 1985, except for the last paragraph, which was

added on October 1, 1988.

That section meaningfully begins with the phrase, "for offenses not subject

to the rule on summary procedure in special cases," which plainly signifies

that the section does not apply to offenses which are subject to summary

procedure. The phrase "in all cases" appearing in the last paragraph

obviously refers to the cases covered by the Section, that is, those offenses

not governed by the Rule on Summary Procedure. This interpretation

conforms to the canon that words in a statute should be read in relation to

and not isolation from the rest of the measure, to discover the true

legislative intent.

As it is clearly provided in the Rule on Summary Procedure that among the

offenses it covers are violations of municipal or city ordinances, it should

follow that the charge against the petitioner, which is for violation of a

municipal ordinance of Rodriguez, is governed by that rule and not Section

1 of Rule 110.

Where paragraph (b) of the section does speak of "offenses falling under

the jurisdiction of the Municipal Trial Courts and Municipal Circuit Trial

Courts," the obvious reference is to Section 32(2) of B.P. No. 129, vesting in

such courts:

(2) Exclusive original jurisdiction over all offenses punishable

with imprisonment of not exceeding four years and two

months, or a fine of not more than four thousand pesos, or both

such fine and imprisonment, regardless of other imposable

accessory or other penalties, including the civil liability arising

from such offenses or predicated thereon, irrespective of kind,

nature, value, or amount thereof; Provided, however, That in

offenses involving damage to property through criminal

negligence they shall have exclusive original jurisdiction where

the imposable fine does not exceed twenty thousand pesos.

These offenses are not covered by the Rule on Summary Procedure.

Under Section 9 of the Rule on Summary Procedure, "the complaint or

information shall be filed directly in court without need of a prior

preliminary examination or preliminary investigation."

6

Both parties agree

that this provision does not prevent the prosecutor from conducting a

preliminary investigation if he wants to. However, the case shall be

deemed commenced only when it is filed in court, whether or not the

prosecution decides to conduct a preliminary investigation. This means

that the running of the prescriptive period shall be halted on the date the

case is actually filed in court and not on any date before that.

This interpretation is in consonance with the afore-quoted Act No. 3326

which says that the period of prescription shall be suspended "when

proceedings are instituted against the guilty party." The proceedings

referred to in Section 2 thereof are "judicial proceedings," contrary to the

submission of the Solicitor General that they include administrative

proceedings. His contention is that we must not distinguish as the law does

not distinguish. As a matter of fact, it does.

At any rate, the Court feels that if there be a conflict between the Rule on

Summary Procedure and Section 1 of Rule 110 of the Rules on Criminal

Procedure, the former should prevail as the special law. And if there be a

conflict between Act. No. 3326 and Rule 110 of the Rules on Criminal

Procedure, the latter must again yield because this Court, in the exercise of

its rule-making power, is not allowed to "diminish, increase or modify

substantive rights" under Article VIII, Section 5(5) of the Constitution.

Prescription in criminal cases is a substantive right.

7

Going back to the Francisco case, we find it not irrelevant to observe that

the decision would have been conformable to Section 1, Rule 110, as the

offense involved was grave oral defamation punishable under the Revised

Penal Code with arresto mayor in its maximum period to prision correccional

in its minimum period. By contrast, the prosecution in the instant case is

for violation of a municipal ordinance, for which the penalty cannot exceed

six months, 8 and is thus covered by the Rule on Summary Procedure.

The Court realizes that under the above interpretation, a crime may

prescribe even if the complaint is filed seasonably with the prosecutor's

office if, intentionally or not, he delays the institution of the necessary

judicial proceedings until it is too late. However, that possibility should not

justify a misreading of the applicable rules beyond their obvious intent as

reasonably deduced from their plain language. The remedy is not a

distortion of the meaning of the rules but a rewording thereof to prevent

the problem here sought to be corrected.

Our conclusion is that the prescriptive period for the crime imputed to the

petitioner commenced from its alleged commission on May 11, 1990, and

ended two months thereafter, on July 11, 1990, in accordance with Section 1

of Act No. 3326. It was not interrupted by the filing of the complaint with

the Office of the Provincial Prosecutor on May 30, 1990, as this was not a

judicial proceeding. The judicial proceeding that could have interrupted

the period was the filing of the information with the Municipal Trial Court

of Rodriguez, but this was done only on October 2, 1990, after the crime

had already prescribed.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED, and the challenged Order dated

October 2, 1991 is SET ASIDE. Criminal Case No. 90-089 in the Municipal

Trial Court of Rodriguez, Rizal, is hereby DISMISSED on the ground of

prescription. It is so ordered.

Narvasa, C.J., Gutierrez, Jr., Paras, Feliciano, Padilla, Bidin, Grio-Aquino,

Medialdea, Regalado, Davide, Jr., Romero, Nocon and Bellosillo, JJ., concur.

Footnotes

1 Rollo, p. 18.

2 Ibid.

3 Id., p. 19; Through Judge Andres B. Reyes, Jr.

4 Id., p. 21

5 122 SCRA 538

6 The phrase "filed directly in court without need of prior

preliminary examination or preliminary investigation" was

deleted under the Revised Rule on Summary Procedure

effective on November 15, 1991.

7 People vs. Castro, 95 Phil. 463.

8 Section 447, Local Government Code.

SECOND DIVISION

ROBERTO BRILLANTE, G.R. Nos. 118757 & 121571

Petitioner,

Present:

PUNO, J.,

Chairman,

- versus - AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ,

CALLEJO, SR.,

TINGA, and

CHICO-NAZARIO, JJ.

COURT OF APPEALS and

THE PEOPLE OF THE

PHILIPPINES, Promulgated:

Respondents.

November 11, 2005

x-------------------------------------------------------------------x

R E S O L U T I O N

TINGA, J.:

This treats of the Motion for Reconsideration dated November 25, 2004

filed by Roberto Brillante (Brillante) assailing the Decision of this Court

dated October 19, 2004 which affirmed his conviction for the crime of libel

but reduced the amount of moral damages he is liable to pay.

Brillante avers that his conviction, without the corresponding

conviction of the writers, editors and owners of the newspapers on which

the libelous materials were published, violates his right to equal

protection. He also claims that he should have been convicted only of one

count of libel because private respondents were not defamed separately as

each publication was impelled by a single criminal intent. Finally, he

claims that there is a semblance of truth to the accusations he hurled at

private respondents citing several instances of alleged violent acts

committed by the latter against his person.

Private respondent Jejomar Binay (Binay) filed a Comment dated

March 3, 2005, maintaining that the equal protection clause does not apply

because there are substantial distinctions between Brillante and his co-

accused warranting dissimilar treatment. Moreover, contrary to Brillantes

claim that he should have been convicted only of one count of libel, Binay

asserts that there can be as many convictions for libel as there are persons

defamed. Besides, this matter should have been raised at the time the

separate complaints were filed against him and not in this motion.

For its part, the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) filed a Comment

dated April 4, 2005, stating that the issues raised in Brillantes motion have

already been discussed and passed upon by the Court. Hence, the motion

should be denied.

Brillante filed a Consolidated Reply dated May 26, 2005 in reiteration of

his arguments.

As correctly noted by the OSG, the basic issues raised in the instant

motion have already been thoroughly discussed and passed upon by the

Court in its Decision. For this reason, we shall no longer dwell on them.

We believe, however, that the penalty of imprisonment imposed

against Brillante should be re-examined and reconsidered. Although this

matter was neither raised in Brillantes petition nor in the instant motion,

we advert to the well-established rule that an appeal in a criminal

proceeding throws the whole case open for review of all its aspects,

including those not raised by the parties.[1]

In Mari v. Court of Appeals,[2] petitioner therein was found guilty of

slander by deed penalized under Art. 359 of the Revised Penal Code (Penal

Code) by either imprisonment or fine. In view of the fact that the offense

was done in the heat of anger and in reaction to a perceived provocation,

the Court opted to impose the penalty of fine instead of imprisonment.

In this case, Brillante claims that on January 6, 1988, his friends

house was bombed resulting in the death of three people. This incident

allegedly impelled him, out of moral and social duty, to call a press

conference on January 7, 1988 with the intention of exposing what he

believed were terrorist acts committed by private respondents against the

electorate of Makati City.

We find that the circumstances surrounding the writing of the open

letter on which the libelous publications were based similarly warrant the

imposition of the penalty of fine only, instead of both imprisonment and

fine, in accordance with Art. 355 of the Penal Code.[3] The intensely

feverish passions evoked during the election period in 1988 must have

agitated petitioner into writing his open letter.

Moreover, while petitioner failed to prove all the elements of

qualified privileged communication under par. 1, Art. 354 of the Penal

Code, incomplete privilege should be appreciated in his favor, especially

considering the wide latitude traditionally given to defamatory utterances

against public officials in connection with or relevant to their performance

of official duties or against public figures in relation to matters of public

interest involving them.[4]

The foregoing circumstances, in our view, justify the deletion of the

penalty of imprisonment and the retention of the meted fine only.

WHEREFORE, the Decision dated October 19, 2004 is AFFIRMED

with MODIFICATION consisting of the deletion of the penalty of

imprisonment imposed upon petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

DANTE O. TINGA

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

REYNATO S. PUNO

Associate Justice

Chairman

MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ ROMEO J. CALLEJO, SR.

Associate Justice Associate Justice

(On Leave)

MINITA V. CHICO-NAZARIO

Associate Justice

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, it is hereby

certified that the conclusions in the above Resolution had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the

Courts Division.

REYNATO C. PUNO

Acting Chief Justice

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 125066. July 8, 1998]

ISABELITA REODICA, petitioner, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, and PEOPLE

OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

DAVIDE, JR., J.:

On the evening of 17 October 1987, petitioner Isabelita Reodica was driving

a van along Doa Soledad Avenue, Better Living Subdivision, Paraaque,

Metro Manila. Allegedly because of her recklessness, her van hit the car of

complainant Norberto Bonsol. As a result, complainant sustained physical

injuries, while the damage to his car amounted to P8,542.00.

Three days after the incident, or on 20 October 1987, the complainant filed

an Affidavit of Complainti[1] against petitioner with the Fiscals Office.

On 13 January 1988, an informationii[2] was filed before the Regional Trial

Court (RTC) of Makati (docketed as Criminal Case No. 33919) charging

petitioner with Reckless Imprudence Resulting in Damage to Property

with Slight Physical Injury. The information read:

The undersigned 2

nd

Asst. Fiscal accuses Isabelita Reodica of the

crime of Reckless Imprudence Resulting in Damage to Property

with Slight Physical Injury as follows:

That on or about the 17

th

day of October, 1987 in the Municipality of

Paraaque, Metro Manila, Philippines and within the jurisdiction of this

Honorable Court, the abovementioned accused, Isabelita Velasco Reodica,

being then the driver and/or person in charge of a Tamaraw bearing plate

no. NJU-306, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously

drive, manage and operate the same in a reckless, careless, negligent and

imprudent manner, without regard to traffic laws, rules and regulations

and without taking the necessary care and precaution to avoid damage to

property and injuries to person, causing by such negligence, carelessness

and imprudence the said vehicle to bump/collide with a Toyota Corolla

bearing plate no. NIM-919 driven and owned by Norberto Bonsol, thereby

causing damage amounting to P8,542.00, to the damage and prejudice of its

owner, in the aforementioned amount of P8,542.00.

That as further consequence due to the strong impact, said Norberto Bonsol

suffered bodily injuries which required medical attendance for a period of

less that nine (9) days and incapacitated him from performing his

customary labor for the same period of time.

Upon arraignment, petitioner pleaded not guilty to the charge. Trial then

ensued.

On 31 January 1991, the RTC of Makati, Branch 145, rendered a

decisioniii[3] convicting petitioner of the quasi offense of reckless

imprudence resulting in damage to property with slight physical injuries,

and sentencing her:

[t]o suffer imprisonment of six (6) months of arresto mayor, and to

pay the complainant, Norberto Bonsol y Atienza, the sum of

Thirteen Thousand Five Hundred Forty-Two (P13,542), Philippine

Currency, without subsidiary impairment in case of insolvency; and

to pay the costs.iv[4]

The trial court justified imposing a 6-month prison term in this wise:

As a result of the reckless imprudence of the accused, complainant

suffered slight physical injuries (Exhs. D, H and I). In view of the

resulting physical injuries, the penalty to be imposed is not fine, but

imprisonment (Gregorio, Fundamental of Criminal Law Review,

Eight Edition 1988, p. 711). Slight physical injuries thru reckless

imprudence is now punished with penalty of arresto mayor in its

maximum period (People v. Aguiles, L-11302, October 28, 1960,

cited in Gregorios book, p. 718).v[5]

As to the sum of P13,542.00, this represented the cost of the car repairs

(P8,542.00) and medical expenses (P5,000.00).

Petitioner appealed from the decision to the Court of Appeals, which

docketed the case as CA-G.R. CR No. 14660. After her motions for

extension of time to file her brief were granted, she filed a Motion to

Withdraw Appeal for Probation Purposes, and to Suspend, Ex Abundanti

Cautela, Period for Filing Appellants Brief. However, respondent Court of

Appeals denied this motion and directed petitioner to file her brief.vi[6]

After passing upon the errors imputed by petitioner to the trial court,

respondent Court of Appeals rendered a decisionvii[7] on 31 January 1996

affirming the appealed decision.

Petitioner subsequently filed a motion for reconsiderationviii[8] raising

new issues, thus:

NOW THAT AN ACQUITTAL SEEMS IMPOSSIBLE, MAY WE

REVISIT THE PENALTY AND MOVE THAT IT BE REVIEWED

AND SET ASIDE SINCE IT IS RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED TO

BE ERROR TO COMPLEX DAMAGE TO PROPERTY AND

SLIGHT PHYSICAL INJURIES, AS BOTH ARE LIGHT OFFENSES,

OVER WHICH THE RESPONDENT COURT HAD NO

JURISDICTION AND EVEN ASSUMING SUCH JURISDICTION,

IT CANNOT IMPOSE A PENALTY IN EXCESS OF WHAT IS

AUTHORIZED BY LAW.ix[9]

. . . . . . . . .

REVERSAL OF THE DECISION REMAINS POSSIBLE ON

GROUNDS OF PRESCRIPTION OR LACK OF

JURISDICTION.x[10]

In its Resolution of 24 May 1996, the Court of Appeals denied petitioners

motion for reconsideration for lack of merit, as well as her supplemental

motion for reconsideration. Hence, the present petition for review on

certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court premised on the following

grounds:

RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS DECISION DATED

JANUARY 31, 1996 AND MORE SO ITS RESOLUTION DATED

MAY 24, 1996, ARE CONTRARY TO LAW AND GROSSLY

ERRONEOUS IN THAT THEY IMPOSED A PENALTY IN EXCESS

OF WHAT IS AUTHORIZED BY LAW FOR THE CRIME OF

RECKLESS IMPRUDENCE RESULTING IN SLIGHT PHYSICAL

INJURIES, ON THE BASIS OF A CLERICAL ERROR IN A

SECONDARY SOURCE.

A IN THE CASE OF PEOPLE V. AGUILAR,xi[11] THE

SAME CASE WHERE THE COURT A QUO BASED ITS

FINDING OF A PENALTY WHEN IT AFFIRMED THE

DECISION OF THE REGIONAL TRIAL COURT, WHAT

WAS STATED IN THE ORIGINAL TEXT OF SAID

CASE IS THAT THE PENALTY FOR SLIGHT

PHYSICAL INJURIES THROUGH RECKLESS

IMPRUDENCE IS ARRESTO MENOR AND NOT

ARRESTO MAYOR. IT IS GRAVE ERROR FOR THE

RESPONDENT COURT TO PUNISH PETITIONER

MORE THAN SHE SHOULD OR COULD BE

PUNISHED BECAUSE OF A CLERICAL ERROR

COPIED FROM A SECONDARY SOURCE.

B. THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY

ABUSED ITS DISCRETION WHEN IT COMPLEXED

THE CRIME OF RECKLESS IMPRUDENCE

RESULTING IN DAMAGE TO PROPERTY AND

SLIGHT PHYSICAL INJURIES IMPOSING A SINGLE

EXCESSIVE PENALTY IN ITS ELLIPTICAL

RESOLUTION OF MAY 24, 1996.

C. THE RESPONDENT COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY

ERRED WHEN IT AFFIRMED THE TRIAL COURTS

DECISION NOTWITHSTANDING THE DEFENSE OF

PRESCRIPTION AND LACK OF JURISDICTION.

Anent the first ground, petitioner claims that the courts below misquoted

not only the title, but likewise the ruling of the case cited as authority

regarding the penalty for slight physical injuries through reckless

imprudence. Concretely, the title of the case was not People v. Aguiles, but

People v. Aguilar; while the ruling was that the penalty for such quasi

offense was arresto menor not arresto mayor.

As regards the second assigned error, petitioner avers that the courts below

should have pronounced that there were two separate light felonies

involved, namely: (1) reckless imprudence with slight physical injuries;

and (2) reckless imprudence with damage to property, instead of

considering them a complex crime. Two light felonies, she insists, do not

rate a single penalty of arresto mayor or imprisonment of six months,

citing Lontok v. Gorgonio,xii[12] thus:

Where the single act of imprudence resulted in double less serious

physical injuries, damage to property amounting to P10,000.00 and

slight physical injuries, a chief of police did not err in filing a

separate complaint for the slight physical injuries and another

complaint for the lesiones menos graves and damage to property

(Arcaya vs. Teleron, L-37446, May 31, 1974, 57 SCRA 363, 365).

. . . . . . . . .

The case of Angeles vs. Jose, 96 Phil. 151, cited by investigating fiscal, is

different from the instant case because in that case the negligent act

resulted in the offenses of lesiones menos graves and damage to property

which were both less grave felonies and which, therefore, constituted a

complex crime.

In the instant case, following the ruling in the Turla case, the offense of

lesiones leves through reckless imprudence should have been charged in

a separate information.

She then suggests that at worst, the penalties of two light offenses, both

imposable in their maximum period and computed or added together,

only sum up to 60 days imprisonment and not six months as imposed by

the lower courts.

On the third assigned error, petitioner insists that the offense of slight

physical injuries through reckless imprudence, being punishable only by

arresto menor, is a light offense; as such, it prescribes in two months. Here,

since the information was filed only on 13 January 1988, or almost three

months from the date the vehicular collision occurred, the offense had

already prescribed, again citing Lontok, thus:

In the instant case, following the ruling in the Turla case, the offense

of lesiones leves through reckless imprudence should have been

charged in a separate information. And since, as a light offense, it

prescribes in two months, Lontoks criminal liability therefor was

already extinguished (Arts. 89[5], 90 and 91, Revised Penal Code in

relation to sec. 2[e] and [f], Rule 117, Rules of Court). The trial court

committed a grave abuse of discretion in not sustaining Lontoks

motion to quash that part of the information charging him with that

light offense.

Petitioner further claims that the information was filed with the wrong

court, since Regional Trial Courts do not deal with arresto menor cases. She

submits that damage to property and slight physical injuries are light

felonies and thus covered by the rules on summary procedure; therefore,

only the filing with the proper Metropolitan Trial Court could have tolled

the statute of limitations, this time invoking Zaldivia v. Reyes.xiii[13]

In its Comment filed on behalf of public respondents, the Office of the

Solicitor General (OSG) agrees with petitioner that the penalty should have

been arresto menor in its maximum period, instead of arresto mayor,

pursuant to Article 365 of the Revised Penal Code.

As to the second assigned error, the OSG contends that conformably with

Buerano v. Court of Appeals,xiv[14] which frowns upon splitting of crimes

and prosecution, it was proper for the trial court to complex reckless

imprudence with slight physical injuries and damage to property because

what the law seeks to penalize is the single act of reckless imprudence, not

the results thereof; hence, there was no need for two separate informations.

To refute the third assigned error, the OSG submits that although the

Municipal Trial Court had jurisdiction to impose arresto menor for slight

physical injuries, the Regional Trial Court properly took cognizance of this

case because it had the jurisdiction to impose the higher penalty for the

damage to property, which was a fine equal to thrice the value of P8,542.00.

On this score, the OSG cites Cuyos v. Garcia.xv[15]

The OSG then debunks petitioners defense of prescription of the crime,

arguing that the prescriptive period here was tolled by the filing of the

complaint with the fiscals office three days after the incident, pursuant to

People v. Cuaresmaxvi[16] and Chico v. Isidro.xvii[17]

In her Reply to the Comment of the OSG, petitioner expressed gratitude

and appreciation to the OSG in joining cause with her as to the first

assigned error. However, she considers the OSGs reliance on Buerano v.

Court of Appealsxviii[18] as misplaced, for nothing there validates the

complexing of the crime of reckless imprudence with physical injuries

and damage to property; besides, in that case, two separate informations

were filed -- one for slight and serious physical injuries through reckless

imprudence and the other for damage to property through reckless

imprudence. She then insists that in this case, following Arcaya v.

Teleronxix[19] and Lontok v. Gorgonio,xx[20] two informations should have

been filed. She likewise submits that Cuyos v. Garciaxxi[21] would only

apply here on the assumption that it was proper to complex damage to

property through reckless imprudence with slight physical injuries

through reckless imprudence. Chico v. Isidroxxii[22] is likewise

inapposite, for it deals with attempted homicide, which is not covered by

the Rule on Summary Procedure.

Petitioner finally avers that People v. Cuaresmaxxiii[23] should not be given

retroactive effect; otherwise, it would either unfairly prejudice her or

render nugatory the en banc ruling in Zaldiviaxxiv[24] favorable to her.

The pleadings thus raise the following issues:

I. Whether the penalty imposed on petitioner is correct.

II. Whether the quasi offenses of reckless imprudence resulting

in damage to property in the amount of P8,542.00 and

reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries are

light felonies.

III. Whether the rule on complex crimes under Article 48 of the

Revised Penal Code applies to the quasi offenses in

question.

IV. Whether the duplicity of the information may be

questioned for the first time on appeal.

V. Whether the Regional Trial Court had jurisdiction over the

offenses in question.

VI. Whether the quasi offenses in question have already

prescribed.

I. The Proper Penalty.

We agree with both petitioner and the OSG that the penalty of six months

of arresto mayor imposed by the trial court and affirmed by respondent

Court of Appeals is incorrect. However, we cannot subscribe to their

submission that the penalty of arresto menor in its maximum period is the

proper penalty.

Article 365 of the Revised Penal Code provides:

Art. 365. Imprudence and negligence. Any person who, by reckless

imprudence, shall commit any act which, had it been intentional,

would constitute a grave felony, shall suffer the penalty of arresto

mayor in its maximum period to prision correccional in its medium

period; if it would have constituted a less grave felony, the penalty

of arresto mayor in its minimum and medium periods shall be

imposed; if it would have constituted a light felony, the penalty of

arresto menor in its maximum period shall be imposed.

Any person who, by simple imprudence or negligence, shall

commit an act which would otherwise constitute a grave felony,

shall suffer the penalty of arresto mayor in its medium and

maximum periods; if it would have constituted a less serious

felony, the penalty of arresto mayor in its minimum period shall be

imposed.

When the execution of the act covered by this article shall have only

resulted in damage to the property of another, the offender shall be

punished by a fine ranging from an amount equal to the value of

said damages to three times such value, but which shall in no case

be less than 25 pesos.

A fine not exceeding 200 pesos and censure shall be imposed upon

any person who, by simple imprudence or negligence, shall cause

some wrong which, if done maliciously, would have constituted a

light felony.

In the imposition of these penalties, the courts shall exercise their

sound discretion, without regard to the rules prescribed in Article

64.

The provisions contained in this article shall not be applicable:

1. When the penalty provided for the offense is equal to or lower than

those provided in the first two paragraphs of this article, in which case the

courts shall impose the penalty next lower in degree than that which

should be imposed in the period which they may deem proper to apply.

According to the first paragraph of the aforequoted Article, the penalty for

reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries, a light felony, is

arresto menor in its maximum period, with a duration of 21 to 30 days. If

the offense of slight physical injuries is, however, committed deliberately

or with malice, it is penalized with arresto menor under Article 266 of the

Revised Penal Code, with a duration of 1 day to 30 days. Plainly, the

penalty then under Article 266 may be either lower than or equal to the

penalty prescribed under the first paragraph of Article 365. This being the

case, the exception in the sixth paragraph of Article 365 applies. Hence, the

proper penalty for reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries

is public censure, this being the penalty next lower in degree to arresto

menor.xxv[25]

As to reckless imprudence resulting in damage to property in the amount

of P8,542.00, the third paragraph of Article 365, which provides for the

penalty of fine, does not apply since the reckless imprudence in this case

did not result in damage to property only. What applies is the first

paragraph of Article 365, which provides for arresto mayor in its minimum

and medium periods (1 month and 1 day to 4 months) for an act committed

through reckless imprudence which, had it been intentional, would have

constituted a less grave felony. Note that if the damage to the extent of

P8,542.00 were caused deliberately, the crime would have been malicious

mischief under Article 329 of the Revised Penal Code, and the penalty

would then be arresto mayor in its medium and maximum periods (2

months and 1 day to 6 months which is higher than that prescribed in the

first paragraph of Article 365). If the penalty under Article 329 were equal

to or lower than that provided for in the first paragraph, then the sixth

paragraph of Article 365 would apply, i.e., the penalty next lower in degree,

which is arresto menor in its maximum period to arresto mayor in its

minimum period or imprisonment from 21 days to 2 months. Accordingly,

the imposable penalty for reckless imprudence resulting in damage to

property to the extent of P8,542.00 would be arresto mayor in its minimum

and medium periods, which could be anywhere from a minimum of 1

month and 1 day to a maximum of 4 months, at the discretion of the court,

since the fifth paragraph of Article 365 provides that in the imposition of

the penalties therein provided the courts shall exercise their sound

discretion without regard to the rules prescribed in article 64.

II. Classification of the Quasi Offense in Question.

Felonies are committed not only by means of deceit (dolo), but likewise by

means of fault (culpa). There is deceit when the wrongful act is performed

with deliberate intent; and there is fault when the wrongful act results from

imprudence, negligence, lack of foresight or lack of skill.xxvi[26]

As earlier stated, reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries is

punishable by public censure only. Article 9, paragraph 3, of the Revised

Penal Code defines light felonies as infractions of law carrying the penalty

of arresto menor or a fine not exceeding P200.00, or both. Since public

censure is classified under Article 25 of the Code as a light penalty, and is

considered under the graduated scale provided in Article 71 of the same

Code as a penalty lower than arresto menor, it follows that the offense of

reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries is a light felony.

On the other hand, reckless imprudence also resulting in damage to

property is, as earlier discussed, penalized with arresto mayor in its

minimum and medium periods. Since arresto mayor is a correctional

penalty under Article 25 of the Revised Penal Code, the quasi offense in

question is a less grave felony not a light felony as claimed by petitioner.

III. Applicability of the Rule on Complex Crimes.

Since criminal negligence may, as here, result in more than one felony,

should Article 48 of the Revised Code on complex crimes be applied?

Article 48 provides as follows:

ART. 48. Penalty for complex crimes. -- When a single act constitutes

two or more grave or less grave felonies, or when an offense is

necessary a means for committing the other, the penalty for the

most serious crime shall be imposed, the same to be applied in its

maximum period.

Clearly, if a reckless, imprudent or negligent act results in two or more

grave or less grave felonies, a complex crime is committed. However, in

Lontok v. Gorgonio,xxvii[27] this Court declared that where one of the

resulting offenses in criminal negligence constitutes a light felony, there is

no complex crime, thus:

Applying article 48, it follows that if one offense is light, there is no

complex crime. The resulting offenses may be treated as separate or

the light felony may be absorbed by the grave felony. Thus, the

light felonies of damage to property and slight physical injuries,

both resulting from a single act of imprudence, do not constitute a

complex crime. They cannot be charged in one information. They

are separate offenses subject to distinct penalties (People vs. Turla,

50 Phil. 1001; See People vs. Estipona, 70 Phil. 513).

Where the single act of imprudence resulted in double less serious

physical injuries, damage to property amounting to P10,000 and

slight physical injuries, a chief of police did not err in filing a

separate complaint for the slight physical injuries and another

complaint for the lesiones menos graves and damage to property

[Arcaya vs. Teleron, L-37446, May 31, 1974, 57 SCRA 363, 365].

Hence, the trial court erred in considering the following felonies as a

complex crime: the less grave felony of reckless imprudence resulting in

damage to property in the amount of P8,542.00 and the light felony of

reckless imprudence resulting in physical injuries.

IV. The Right to Assail the Duplicity of the Information.

Following Lontok, the conclusion is inescapable here, that the quasi offense

of reckless imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries should have

been charged in a separate information because it is not covered by Article

48 of the Revised Penal Code. However, petitioner may no longer

question, at this stage, the duplicitous character of the information, i.e.,

charging two separate offenses in one information, to wit: (1) reckless

imprudence resulting in damage to property; and (2) reckless imprudence

resulting in slight physical injuries. This defect was deemed waived by her

failure to raise it in a motion to quash before she pleaded to the

information.xxviii[28] Under Section 3, Rule 120 of the Rules of Court,

when two or more offenses are charged in a single complaint or

information and the accused fails to object to it before trial, the court may

convict the accused of as many offenses as are charged and proved and

impose on him the penalty for each of them.xxix[29]

V. Which Court Has Jurisdiction Over the

Quasi Offenses in Question.

The jurisdiction to try a criminal action is to be determined by the law in

force at the time of the institution of the action, unless the statute expressly

provides, or is construed to the effect that it is intended to operate as to

actions pending before its enactment.xxx[30]

At the time of the filing of the information in this case, the law in force was

Batas Pambansa Blg. 129, otherwise known as The Judiciary

Reorganization Act of 1980. Section 32(2)xxxi[31] thereof provided that

except in cases falling within the exclusive original jurisdiction of the

Regional Trial Courts and of the Sandiganbayan, the Metropolitan Trial

Courts (MeTCs), Municipal Trial Courts (MTCs), and Municipal Circuit

Trial Courts (MCTCs) had exclusive original jurisdiction over all offenses

punishable with imprisonment of not exceeding four years and two

months, or a fine of not more than four thousand pesos, or both fine and

imprisonment, regardless of other imposable accessory or other penalties,

including the civil liability arising from such offenses or predicated

thereon, irrespective of kind, nature, value or amount thereof.

The criminal jurisdiction of the lower courts was then determined by the

duration of the imprisonment and the amount of fine prescribed by law for

the offense charged. The question thus arises as to which court has

jurisdiction over offenses punishable by censure, such as reckless

imprudence resulting in slight physical injuries.

In Uy Chin Hua v. Dinglasan,xxxii[32] this Court found that a lacuna existed

in the law as to which court had jurisdiction over offenses penalized with

destierro, the duration of which was from 6 months and 1 day to 6 years,

which was co-extensive with prision correccional. We then interpreted the

law in this wise:

Since the legislature has placed offenses penalized with arresto

mayor under the jurisdiction of justice of the peace and municipal

courts, and since by Article 71 of the Revised Penal Code, as

amended by Section 3 of Commonwealth Act No. 217, it has placed

destierro below arresto mayor as a lower penalty than the latter, in the

absence of any express provision of law to the contrary it is logical

and reasonable to infer from said provisions that its intention was

to place offenses penalized with destierro also under the jurisdiction

of justice of the peace and municipal courts and not under that of

courts of first instance.

Similarly, since offenses punishable by imprisonment of not exceeding 4

years and 2 months were within the jurisdictional ambit of the MeTCs,

MTCs and MCTCs, it follows that those penalized with censure, which is a

penalty lower than arresto menor under the graduated scale in Article 71 of

the Revised Penal Code and with a duration of 1 to 30 days, should also fall

within the jurisdiction of said courts. Thus, reckless imprudence resulting

in slight physical injuries was cognizable by said courts.

As to the reckless imprudence resulting in damage to property in the

amount of P8,542.00, the same was also under the jurisdiction of MeTCs,

MTCs or MCTCs because the imposable penalty therefor was arresto mayor

in its minimum and medium periods -- the duration of which was from 1

month and 1 day to 4 months.

Criminal Case No. 33919 should, therefore, be dismissed for lack of

jurisdiction on the part of the RTC of Makati.

VI. Prescription of the Quasi Offenses in Question.

Pursuant to Article 90 of the Revised Penal Code, reckless imprudence

resulting in slight physical injuries, being a light felony, prescribes in two

months. On the other hand, reckless imprudence resulting in damage to

property in the amount of P8,542.00, being a less grave felony whose

penalty is arresto mayor in its minimum and medium periods, prescribes in

five years.

To resolve the issue of whether these quasi offenses have already

prescribed, it is necessary to determine whether the filing of the complaint

with the fiscals office three days after the incident in question tolled the

running of the prescriptive period.

Article 91 of the Revised Penal Code provides:

ART. 91. Computation of prescription of offenses. -- The period of

prescription shall commence to run from the day on which the

crime is discovered by the offended party, the authorities, or their

agents, and shall be interrupted by the filing of the complaint or

information, and shall commence to run again when such

proceedings terminate without the accused being convicted or

acquitted, or are unjustifiably stopped by any reason not imputable

to him. (emphasis supplied)

Notably, the aforequoted article, in declaring that the prescriptive period

shall be interrupted by the filing of the complaint or information, does

not distinguish whether the complaint is filed for preliminary examination

or investigation only or for an action on the merits.xxxiii[33] Thus, in

Francisco v. Court of Appealsxxxiv[34] and People v. Cuaresma,xxxv[35] this

Court held that the filing of the complaint even with the fiscals office

suspends the running of the statute of limitations.

We cannot apply Section 9xxxvi[36] of the Rule on Summary Procedure,

which provides that in cases covered thereby, such as offenses punishable

by imprisonment not exceeding 6 months, as in the instant case, the

prosecution commences by the filing of a complaint or information directly

with the MeTC, RTC or MCTC without need of a prior preliminary

examination or investigation; provided that in Metropolitan Manila and

Chartered Cities, said cases may be commenced only by information.

However, this Section cannot be taken to mean that the prescriptive period

is interrupted only by the filing of a complaint or information directly with

said courts.

It must be stressed that prescription in criminal cases is a matter of

substantive law. Pursuant to Section 5(5), Article VIII of the Constitution,

this Court, in the exercise of its rule-making power, is not allowed to

diminish, increase or modify substantive rights.xxxvii[37] Hence, in case of

conflict between the Rule on Summary Procedure promulgated by this

Court and the Revised Penal Code, the latter prevails.

Neither does Zaldivia control in this instance. It must be recalled that what

was involved therein was a violation of a municipal ordinance; thus, the

applicable law was not Article 91 of the Revised Penal Code, but Act. No.

3326, as amended, entitled An Act to Establish Periods of Prescription for

Violations Penalized by Special Acts and Municipal Ordinances and to

Provide When Prescription Shall Begin to Run. Under Section 2 thereof,

the period of prescription is suspended only when judicial proceedings are

instituted against the guilty party. Accordingly, this Court held that the

prescriptive period was not interrupted by the filing of the complaint with

the Office of the Provincial Prosecutor, as such did not constitute a judicial

proceeding; what could have tolled the prescriptive period there was only

the filing of the information in the proper court.

In the instant case, as the offenses involved are covered by the Revised

Penal Code, Article 91 thereof and the rulings in Francisco and Cuaresma

apply. Thus, the prescriptive period for the quasi offenses in question was

interrupted by the filing of the complaint with the fiscals office three days

after the vehicular mishap and remained tolled pending the termination of

this case. We cannot, therefore, uphold petitioners defense of prescription

of the offenses charged in the information in this case.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is GRANTED. The challenged decision

of respondent Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CR No. 14660 is SET ASIDE as

the Regional Trial Court, whose decision was affirmed therein, had no

jurisdiction over Criminal Case No. 33919.

Criminal Case No. 33919 is ordered DISMISSED.

No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

Bellosillo, Vitug, Panganiban, and Quisumbing, JJ., concur.

i[1] Original Record (OR), 131.

ii[2] Id., 1.

iii[3] Annex C of Petition, Rollo, 52-56. Per Judge Job B. Madayag.

iv[4] Rollo, 56.

v[5] Id.

vi[6] Rollo, 35.

vii[7] Annex A of Petition, Rollo, 27-49. Per Mabutas, Jr., R., J. with

Elbinias, J., and Valdez, Jr., S., JJ., concurring.

viii[8] Annex D of Petition, Rollo, 57-69.

ix[9] Id., 58.

x[10] Id., 60.

xi[11] Erroneously cited by the trial court as People v. Aguiles.

xii[12] 89 SCRA 632, 636 [1979].

xiii[13] 211 SCRA 277 [1992].

xiv[14] 115 SCRA 82 [1982].

xv[15] 160 SCRA 302 1988].

xvi[16] 172 SCRA 415, [1989].

xvii[17] A.M. MTJ-91-559, 13 October 1993.

xviii[18] Supra note 14.

xix[19] 57 SCRA 363 [1974].

xx[20] Supra note 12.

xxi[21] Supra note 15.

xxii[22] Supra note 17.

xxiii[23] Supra note 16.

xxiv[24] Supra note 14.

xxv[25] Article 71 of the Revised Penal Code; People v. Leynez, 65 Phil. 608,

610-611 [1938].

xxvi[26] Article 3, Revised Penal Code.

xxvii[27] Supra note 12 at 635-636.

xxviii[28] Section 8, Rule 117, Rules of Court.

xxix[29] See also People v. Conte, 247 SCRA 583 [1995].

xxx[30] People v. Velasco, 252 SCRA 135 [1996].

xxxi[31] This Section has been amended by Section 2 of R.A. No. 7691,

which was approved by President Fidel V. Ramos on 25 March 1994. As

amended, the provision now reads in part as follows:

Section 32. Jurisdiction of Metropolitan Trial Courts, Municipal Trial

Courts and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts in Criminal Cases. -- Except in

cases falling within the exclusive original jurisdiction of Regional Trial

Courts and Sandiganbayan, the Metropolitan Trial Courts, Municipal Trial

Courts, and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts shall exercise:

(2) Exclusive original jurisdiction over all offenses punishable with

imprisonment not exceeding six (6) years irrespective of the amount of fine,

and regardless of other imposable accessory or other penalties, including

the civil liability arising from such offenses or predicated thereon,

irrespective of kind, nature, value or amount thereof: Provided, however,

That in offenses involving damage to property through criminal

negligence, they shall have exclusive original jurisdiction thereof.

xxxii[32] 86 Phil. 617 [1950].

xxxiii[33] People v. Olarte, 19 SCRA 494 [1967].

xxxiv[34] 122 SCRA 538 [1983].

xxxv[35] Supra note 16.

xxxvi[36] Now Section 11 of the Revised Rules of Summary Procedure,

which reads in part as follows:

SEC. 11. How commenced. -- The filing of criminal cases falling

within the scope of this Rule shall be either by complaint or information:

Provided, however, that in Metropolitan Manila and in Chartered Cities,

such cases shall be commenced only by information, except when the

offense cannot be prosecuted de oficio.

xxxvii[37] Zalvidia v. Reyes, supra note 13 at 284.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)