Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sociological Review: American

Uploaded by

Marcelo SampaioOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sociological Review: American

Uploaded by

Marcelo SampaioCopyright:

Available Formats

American

SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Volume 1 APRIL, 1936 Number 2

SUCCESSION, AN ECOLOGICAL CONCEPT

ROBERT E. PARK

University oj Chicago

T

HE TERM "succession" seems to have first gained currency and

definition as a result of its use in the writings of the plant ecolo-

gists. It has not the same wide application in animal ecology,

and where it has been used elsewhere, as it has hy sociological

writers, it seems to he a useful word hut without as yet any very pre-

cise connotation. It has heen used, for example, in descrihing the

intra-mural movements and shiftings of population incident to the

growth of the city and of its various "natural areas."

It has heen observed, for one thing, that immigrant peoples

ordinarily settle first in or near the centers of cities, in the so-called

areas of transition. From there they are likely to move hy stages

(perhaps one might hetter say, hy leaps and hounds) from an area

of first to areas of second and third settlement, generally in the direc-

tion of the periphery of the city and eventually into the suhurhan

areain any case, from a less to a more stable section of the metro-

politan region. To these movements, seeing in them the effects of

natural tendencies in the life of the urhan community, students have

applied the term "succession."

In this same sense the term has heen applied to the successive

waves hy which the frontier in America advanced from the Atlantic

seaboard westward across the plains to the Pacific coast, each ad-

vance marked hy a different type of culture and by a different occu-

pational and personality type.

171

172 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

First arrivals were the explorers, trappers, Indian traders, and

prospectors, with a sprinkling of outlaws. In the next line of advance

were land seekers, squatters and frontier farmers bent on establish-

ing the first frontier settlements. They were followed finally hy a

swarm of restless enterprising adventurers of all sorts, among them

representatives of a frontier intelligentsiathe men who eventually

hecame the lawyers, politicians, and newspaper men of the booming

settlements.^

A similar "territorial succession" may be said to have marked the

expansion of European population and European culture during the

period of four hundred years in which European commerce has made

its conquest of the world.^

In a study of Lowell, made hy George F. Kenngott and puhlished

in 1912, the most striking feature of the study was the succession of

immigrant invasions which in the course of the city' s history, i.e.,

from ahout 1830 to ahout 1912, the steady demand for lahor in the

woolen mills had brought to it. This was a study in population suc-

cession, though not so designated. I t was also a study in progressive

cultural changea progress, however, t hat was mostly for the worse.'

Although the term succession, as originally employed by sociolo-

gists, would seem to be more appropriately applied to movements of

population and to such incidental social and cultural changes as

these movements involve, there seems to he no sound reason why

the same term should not he used to descrihe any orderly and ir-

reversible series of events, provided they are to such an extent cor-

related with other less ohvious and more fundamental social changes

t hat they may be used as indices of these changes.

Thus a series of fundamental inventions like the alphahet, the

printing press, the newspaper,and the radio may he said to constitute

a succession. At any rate, each may be said to mark an epoch in the

history of communication, and in doing this each new invention

characterizes the culture of which it is a part and defines its place in

the historical succession. In the same sense we may speak of the

waterwheel as in the same line of succession as the steam engine and

the electric motor, each marking a phase in the evolution of the

machine age. Manifestly such a series of events represents something

more than a mere temporalsequence.lt represents rather an irrevers-

' Rupert B. Vance, "Frontier: Geographical and Social Aspect," Ency. of Soc. Scis.

' E. B. Reuter, Race and Culture Contacts, chap. V.

' George F. Kenngott, The Record of a City: A Social Survey of Lowell, Massachusetts,

N.Y., 1912.

SUCCESSION, AN ECOLOGICAL CONCEPT 173

ible series in which each succeeding event is more or less completely

determined by the one that preceded it.

In a recent paper by Edgar T. Thompson on the plantation- as an

institution of the frontier, the author refers to the fact that a typical

plantation society ordinarily passes through a cycle of change, the

plantation cycle, and to this he applies the term succession. There-

upon he proceeds to describe in detail the irreversible stages in the

natural history of the plantation community.^

In a recent study of the "granger movements" in the United

States, Thomas C. McCormick pointed out that the different indi-

vidual movements seemed to be merely the periodic outbreaks of a

disease that was endemic in the country, so that the different move-

ments might well be conceived as the recurrent manifestations, the

periodic risings and subsidings, of discontents that had their source

and origin in a kind of permanent malaise that could be relieved but

never quite cured.^

Among other things interesting from the point of view of succes-

sion which this study showed were: (i) each succeeding rural move-

ment was under way and rising before the one preceding it had

wholly subsided: (2) although each wave of utopianism was incon-

tinently followed by a corresponding period of depression and disil-

lusionment, there was, nevertheless, evidence with each recurring

wave of a growing realism in the attitudes of the leaders at least.

This was manifest in the character of the programs and in the

methods for putting them into effect. This is an instance of succession

in the psychic or subjective aspect of social change.

A more obvious and impressive example of succession, in the very

elementary sense in which this term is here used, is the procession of

peoples that have invaded and settled South Africa. First came the

Bushmen; they were hunters who have left in caves in the moun-

tains, as records of their presence, interesting rock pictures. The

Hottentots followed. They were hunters, to be sure, but herdsmen

also, and they had a great deal of trouble with the Bushmen who

killed their cattle with poisoned arrows. So the Hottentots drove

the Bushmen into the Kalahari desert. The Bantu were next. They

were hunters and herdsmen but they were more. They cultivated

the soil and raised Kaffir corn.

' Edgar T. Thompson, "Population Expansion and Plantation System." Amer. Jour, of

i'oao/., 41,3 (Nov., 1931), pp. 314-326.

' Thomas C. McCormick, The Rural Life Movement, unpublished thesis, The University

of Chicago.

174 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Later still came the Boers, particularly the voortrekkers, who

settled the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, conquered and

enslaved the natives, settled on the land, raised large families, and

lived on their wide acres in patriarchal style. Although they were

descendants, for the most part, of the earlier Dutch immigrants,

with a sprinkling of Huguenots and other Europeans, they had he-

come, as a result of their isolation and their long association with the

country, an indigenous folk, having their own language, their own

customs and culture.

Then, finally, came the English. They were a sophisticated city

folk, and they came in force only after diamonds were discovered in

Orange Free State in 1867 and gold was discovered in the Transvaal

in 1884. They huilt Johanneshurg, a cosmopolitan citya world

city, in fact, like Calcutta, and Shanghai, and London. In this way

they drew South Africa out of its isolation into the current of inter-

national trade and the new world civilization.

What makes this instance of succession ecologically interesting is

the fact that it illustrates a principle familiar to ethnologists: the

principle, namely, that the more primitive the culture of a people

the larger the territory needed, in proportion to its numhers, to

support its population. A corollary of this is the principle that the

land eventually goes to the race or people that can get the most

out of it. This, on the other hand, is merely another version of the

rule of agricultural economics, which declares that the best lands

eventually go to the best farmers.

The thing that makes the settlement of South Africa relevant and

significant, as an example of succession, is the fact that it seems to

represent not a casual sequence of events hut the consequences of an

inexorahle historical process.

It is evident that in the conception of succession, as here defined

and illustrated, there is implicit a more fundamental notion of social

change and of society which is nowhere explicitly set forth.

Generally speaking, succession, as the term is used by ecologists,

seems to be identical with a notion of social change suggested hy

Walter Bagehot's phrase, "the cake of custom," in his volumePAy.f-

ics and Politics; a conception which has heen further elahorated by

Frederick Jackson Teggart in his Theory of History.^

' Walter Bagehot, Physics and Politics; or Thoughts on the Application of the Principles of

"Natural Section" and "Inheritance" to Political Society, N.Y., 1873; and Frederick Jackson

Teggart, Theory of History.

SUCCESSION, AN ECOLOGICAL CONCEPT 17s

Teggart's is what I have described as the catastrophic theory of

history; the theory that each succeeding social order has its origin in

the conditions created by the earlier; that society is continually re-

born, but that now and then a new and fundamentally different

society emerges. In that case, it emerges suddenly and abruptly

with the accumulation of minor changes in the course of a long-term

trend.

The changes here referred to, have taken place upon the cultural,

rather than the biotic level. Nevertheless, they seem to be identical

in form, at least, with the kind of change that plant and animal ecolo-

gists have called succession, the nature of which is elaborately set

forth by F. C. Clements.'

On the other hand, the conception of social relations and society

on which this account of succession is based is that suggested by J.

Arthur Thompson's description of "the web of life" as "a system of

inter-related lives." This is a notion that had its origin in a long

series of observations and reflections like those from which Darwin

arrived at his theory of the origin of the species. It is this concept

of a symbiotic society based on physiological correlation rather than

culture which has been adopted and elaborated in writings of the

plant and animal ecologists.

Perhaps I can make clear the connection of these conceptions of

society and social change with the ecological conception of succes-

sion if I state briefly certain points of evolutionary and ecological

theory. In brief, then, the argument is this:

Man is involved, with all the hosts of other living creatures, in

what Darwin calls "the web of life." In certain places and under

certain conditions this interdependence of the species, to which

Darwin's expression "the web of life" refers, assumes a relatively

permanent, structural character. This is true of the so-called plant

and animal communities.

The same biotic interdependence of individuals and species, which

has been observed and studied in plant and animal communities,

seems to exist likewise on the human level, except for the fact that in

human society competition and the struggle for existence are limited

by custom, convention, and law. In short, human society is, or ap-

pears to be, organized on two levels, the biotic and the cultural.

We may distinguish between a society based on symbiosis, and one

based on communication and consensus. As a matter of fact, however,

' F. C. Clements, Plant Succession, Washington, D.C., Carnegie Institution, 1916.

176 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

the two are but different aspects of one society. The cultural super-

structure rests on the basis of a symbiotic substructure, and the

emergent energies t hat manifest themselves on the biotic level in

movements and actions which are obvious enough reveal themselves

on the higher, social level in more subtle and sublimated forms. The

distinction and relation between the two levels of society, the biotic

and the cultural, is, or seems to be, analogous to t hat between the

somatic and psychic aspects of the individual organisms of which the

society is composed.

Economic competition, as one meets it in human society, is the

struggle for existence, as Darwin conceived it, modified and limited

by custom and convention. In other respects, however, it is not dif-

ferent from competition as it exists in plant and animal communities.

Society, in the more inclusive sense in which ecologists have de-

fined it, may be said to exist wherever competition has established

some sort of order or war has established some sort of peace. I t is

the area within which an intrinsic and functional social order has

succeeded one that was extrinsic and mechanical. This does not

imply that the original relations of men were, as Hobbes described

them, a war of each against all, a bellum omnia contra omnes, but

rather t hat the function and effect of competition has been to bring

about everywhere a division of labor which has diminished competi-

tion. In the same sense the function of war has been to achieve peace

and order, and to create a social organization capable of maintaining

it.

There is this difference, however, between a symbiotic and cultural

society: namely, t hat the restraint in the case of symbiotic society

(as for example in the plant community) is physical and external. In

the case of cultural, i.e., human, society the restraints upon the in-

dividual are, so to speak, internal and moral, i.e., based on some

sort of consensus.

A social organization on either the biotic or social level, so far as it

involves the incorporation of individuals into a more intimate asso-

ciation, imposes limits, control, and direction upon these individual

units. One may regard the plant and animal community as an asso-

ciation t hat is wholly anarchic and free. In t hat case, however, every

form of association on the cultural level will involve a limitation of

freedom of the individual.

The individual man, although he has more freedom in some places

than in othersmore freedom on the economic level than upon the

SUCCESSION, AN ECOLOGICAL CONCEPT 177

political, more upon the political than the custom or moral level

never has in human society the same absolute freedom to compete

with other individuals that plants and animals have.

Competition implies the existence of what J. Arthur Thompson

describes as "the self-assertiveness and insurgence of the creature."

The adaptations and accommodations which make society possible

are for the individual organism or the individual species a partial or

temporary solution of its struggles to survive.^ But they limit free-

dom.

As the equilibrium we call society becomes relatively fixed in

social structure, competition is increasingly diminished. Neverthe-

less, competition persists in human society and continues to mani-

fest itself, as does the sexual instinct, in manifold indirect and in-

sidious ways.

Every now and then something occurs, however, to disturb the

biotic balance and the social equilibrium, thus tending to undermine

the existing social order. It may be the advent of a new insect pest,

like the boll weevil, or the arrival of a newly invented and perfected

artifact, like the automobile. Under these circumstances, forces and

tendencies formerly held in check are released, and a period of in-

tense activity and rapid change ensues which then continues until

the cycle is completed and a new biotic and social equilibrium is

achieved.

Changes, when they are recurrent, so that they fall into a temporal

or spatial seriesparticularly if the series is of such a sort that the

effect of each succeeding increment of change reenforces or carries

forward the effects of the precedingconstitute what is described in

this paper as succession.

In view, however, of the complexity of social change and of the

peculiar manner in which change in the social superstructure is in-

volved in change in the biotic or symbiotic substructure, it seems

desirable to include within the perspective and purview of the con-

cept, and of the studies of succession, every possible form of orderly

change so far as it affects the interrelations of individuals in a com-

munity or the structure of the society of which these individual units

are a part.

Conceived in this way succession will include studies of the form

(morphology) and of the causes (etiology) of social change.

' "The living creature is by its very nature insurgent and it finds itself encompassed by

limitations and difficulties" (Thompson, op. cit., p. 294).

178 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Sometimes the forms of social change are such, as in the case of

periodic "psychic epidemics" or recurrent business booms, t hat their

courses can be precisely described in a mathematical equation. In

t hat case it may be possible to predict, with some accuracy, not

merely the direction but the duration of change.

Studies of succession, however, seek less to predict the course of

change than to make change intelligible, so t hat it can eventually be

controlled by technical devices or political measures. For this reason

studies of succession are concerned not only with the form which

change takes but even more with the circumstances and events

which precede, accompany, and follow changein short, with its

natural history.

The study of succession involves, it seems, not merely the life-

cycle of individual types of institution and society, but eventually a

study of processes by which new types of society are incubated and,

eventually, by which a new social order emerges from the lap of the

old.

The problems with which plant and animal ecology have tradi-

tionally been concerned are fundamentally population problems.

Society, from the ecological point of view is, like the nat ural as op-

posed to the institutional family, a symbiotic rat her t han a social

unit. I t is a population settled and limited to its habi t at . The ties

t hat unite its individual units are those of a free and nat ural econ-

omy, based on a nat ural division of labor. Such a society is territo-

rially organized, and the ties which hold it together are physical and

vital rat her t han customary and moral. I t is, of course, not assumed

t hat this is all of society, but it is one aspect of it.

The changes in which ecology is interested, it follows, are primarily

physical and vital. They are the movements of population and of ar-

tifacts (commodities), changes in location and in occupationany

sort of change, in fact, which affects an existing division of labor or

the relation of the population to the soil.

Human ecology, in approaching the study of society from the as-

pect presented by its biotic substructure, assumes t hat the origin of

social change, if one could trace it to its source, would be found in

the struggle for existence and in the growth, the migration, the mo-

bility, and the territorial and occupational distribution of peoples

which this struggle has brought about.

Ecology conceives society as fundamentally a territorial as well

as a cultural organization. So far as this conception is valid, it as-

SUCCESSION, AN ECOLOGICAL CONCEPT 179

sumes that most if not all cultural changes in society will be corre-

lated with changes in its territorial organization, and every change

in the territorial and occupational distribution of the population will

effect changes in the existing cultures.

The evolution of society is, therefore, in one of its aspects, the

evolution of a territorial organization. Thus, N. B. S. Gras, in his

Introduction to Economic History, is able to tell the whole story of

economic history by describing the evolution of the metropolitan

economy as it has developed through a series of stages which include

the village, the town, and the city, and which ends in the metro-

politan economy.^

In a similar way, the present economic, political and cultural or-

der in Europe has come into existence with the growth in population

and the migration and the territorial expansion of Europe. This ex-

pansion has been made possible by a series of inventions which have,

at different epochs in its history, revolutionized and transformed the

prevailing methods of transportation and communication. They are:

(1) The perfecting of ocean-going ships with which, in the age of

discovery, Europeans extended their knowledge of the world outside

of Europe.

(2) The steamship, by means of which a great commercial high-

way has been established around the world and has made of the

seas, with their seaport cities, the center of the world.

(3) The railways, by which the continental areas have been pene-

trated and their resources transported to the seaboard, where they

have entered into world commerce.

(4) The automobile, which has suddenly further transformed con-

tinental areas by spreading out over the land networks of roads

which permit rapid and unlimited transportation in every direction.

(5) Finally, there is the airplane, the possibilities of which we are

now just beginning to explore.

These changes have literally plowed up the ancient landmarks,

undermined the influence of the traditional social order in every

part of the world, and released immense social forces which are now

seeking everywhere a new equilibrium.

It is from the point of view of these spatial and temporal changes

in the interrelation of human beings t"hat ecology seeks to investigate

the processes and mechanisms of social and cultural change.

' N. B. S. Gras, An Introduction to Economic History, N.Y., 1922.

You might also like

- Sahlins - Goodbye To Triste TropesDocument25 pagesSahlins - Goodbye To Triste TropeskerimNo ratings yet

- Eric Wolf's Landmark Study of Global History and the People Without HistoryDocument13 pagesEric Wolf's Landmark Study of Global History and the People Without HistoryErik ThylacineNo ratings yet

- Greenblatt - Cultural Mobility - IntromanifestoDocument28 pagesGreenblatt - Cultural Mobility - IntromanifestoEvelyn AmayaNo ratings yet

- Oxford University Press, American Historical Association The American Historical ReviewDocument3 pagesOxford University Press, American Historical Association The American Historical ReviewJavier BenetNo ratings yet

- Stagesofsocial Development: B. R. MannDocument2 pagesStagesofsocial Development: B. R. Mannfatty_mvNo ratings yet

- Burchell and Gray - The American WestDocument22 pagesBurchell and Gray - The American WestgozappariNo ratings yet

- Worster, Doing Environmental HistoryDocument14 pagesWorster, Doing Environmental HistoryjoshBen100% (2)

- Leo Marx-The Machine in The GardenDocument210 pagesLeo Marx-The Machine in The GardenMiguel Angel Gaete100% (2)

- McCants TextDocument11 pagesMcCants TextasadasdaNo ratings yet

- Modernity at Large Cultural Dimensions of GlobalizationDocument12 pagesModernity at Large Cultural Dimensions of Globalizationsarrob162No ratings yet

- From Vernacularism To Globalism - Nazar AlsayyadDocument12 pagesFrom Vernacularism To Globalism - Nazar AlsayyadNegar SBNo ratings yet

- Evirment Policies of British IndiaDocument11 pagesEvirment Policies of British IndiaShivansh PamnaniNo ratings yet

- The Problem: Herskovits, Melville J. (1938) Acculturation: The Study of Culture Contact. Nueva York: J. J. AugustinDocument32 pagesThe Problem: Herskovits, Melville J. (1938) Acculturation: The Study of Culture Contact. Nueva York: J. J. Augustincorell90No ratings yet

- L A Poblacibn Negra de M6Xxic0, 1519-1810:: Beltran. (Xi, 347 Pp. Ediciones Fuente Cultural, Mkxico, DDocument2 pagesL A Poblacibn Negra de M6Xxic0, 1519-1810:: Beltran. (Xi, 347 Pp. Ediciones Fuente Cultural, Mkxico, Dmoor602No ratings yet

- Sidney Mintz and Caribbean StudiesDocument6 pagesSidney Mintz and Caribbean StudiesLaís MaiaNo ratings yet

- Marc Augé - in The Metro (2002)Document145 pagesMarc Augé - in The Metro (2002)Habib H Msallem100% (1)

- Blum - The European Village As CommunityDocument23 pagesBlum - The European Village As CommunityLiviu MantaNo ratings yet

- Beyond Dimorphism (2009)Document27 pagesBeyond Dimorphism (2009)Francesca CioèNo ratings yet

- Nativ Culture South AmericaDocument35 pagesNativ Culture South AmericaMomo BlagovcaninNo ratings yet

- Africa and The Early American Republic: CommentsDocument9 pagesAfrica and The Early American Republic: CommentsKatherin PovedaNo ratings yet

- Writing Global History (Or Trying To) : John DarwinDocument16 pagesWriting Global History (Or Trying To) : John DarwinVth SkhNo ratings yet

- Herskovits, Melville J. (1938) Acculturation: The Study of Culture ContactDocument163 pagesHerskovits, Melville J. (1938) Acculturation: The Study of Culture Contactekchuem100% (5)

- deep-down-time-political-tradition-in-central-africaDocument22 pagesdeep-down-time-political-tradition-in-central-africaIago Goncalves de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Ways of The WorldDocument19 pagesChapter 4 - Ways of The WorldyennhivucaoNo ratings yet

- Burke, A Case of Cultural Hybridity. The European Renaissance (2012)Document29 pagesBurke, A Case of Cultural Hybridity. The European Renaissance (2012)Lorenzo BartalesiNo ratings yet

- Melville Herskovits-AcculturationDocument172 pagesMelville Herskovits-AcculturationruizrocaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 5Document7 pagesArticulo 5Villamil AbrilNo ratings yet

- The Frontier in American History, byDocument190 pagesThe Frontier in American History, bylola larvale0% (1)

- The Other West: Latin America from Invasion to GlobalizationFrom EverandThe Other West: Latin America from Invasion to GlobalizationRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- BAUER NORTON Introduction Entangled Trajectories Indigenous and European HistoriesDocument17 pagesBAUER NORTON Introduction Entangled Trajectories Indigenous and European HistoriesJKNo ratings yet

- Dreams of Europe and Western Civilization: Culture and FrontiersDocument15 pagesDreams of Europe and Western Civilization: Culture and Frontiersyogeshwithraj3914No ratings yet

- England's Social Upheaval After the Black DeathDocument34 pagesEngland's Social Upheaval After the Black DeathJoel HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Isaacman, Allen. The Prazeros As TransfrontiersmenDocument40 pagesIsaacman, Allen. The Prazeros As TransfrontiersmenDavid RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Tradition and The New Social Movements The Politics of Isthmus Zapotec Culture PDFDocument16 pagesTradition and The New Social Movements The Politics of Isthmus Zapotec Culture PDFmekanizmNo ratings yet

- Jack Goldestone - THE PROBLEM OF THE EARLY MODERN WORLD - TEXT PDFDocument36 pagesJack Goldestone - THE PROBLEM OF THE EARLY MODERN WORLD - TEXT PDFBojanNo ratings yet

- Academy of American Franciscan HistoryDocument36 pagesAcademy of American Franciscan HistoryCESAR HUAROTO DE LA CRUZNo ratings yet

- REDFILED, Robert. Tezpoztlan - A Mexican VillageDocument311 pagesREDFILED, Robert. Tezpoztlan - A Mexican VillageLucas MarquesNo ratings yet

- How About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldFrom EverandHow About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- The American Frontier ThesisDocument16 pagesThe American Frontier ThesisHornmaster111No ratings yet

- The Frontier In American History By Frederick Jackson TurnerFrom EverandThe Frontier In American History By Frederick Jackson TurnerNo ratings yet

- The Culture of Culture ContactDocument25 pagesThe Culture of Culture ContactBarbamilieNo ratings yet

- Transatlantic Caribbean: Dialogues of People, Practices, IdeasFrom EverandTransatlantic Caribbean: Dialogues of People, Practices, IdeasNo ratings yet

- Sahlins 1993 Goodby To Tristes Tropes - Ethnography in The Context of Modern World HistoryDocument26 pagesSahlins 1993 Goodby To Tristes Tropes - Ethnography in The Context of Modern World HistorydrosenblNo ratings yet

- Sahlins Goodbye TristesTropesDocument26 pagesSahlins Goodbye TristesTropesMaurício CostaNo ratings yet

- Sydney MintzDocument17 pagesSydney MintzVanessa HernándezNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Local Cultures and Global DynamicsDocument4 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Local Cultures and Global DynamicsKurt ReyesNo ratings yet

- Left Wing Democracy in the English Civil War - A Study of the Social Philosophy of Gerrard WinstanleyFrom EverandLeft Wing Democracy in the English Civil War - A Study of the Social Philosophy of Gerrard WinstanleyNo ratings yet

- 2 - Tomaney - IEHG - RegionDocument15 pages2 - Tomaney - IEHG - RegionMelisa AngelinaNo ratings yet

- Sidney Mintz's Caribbean - ScottDocument20 pagesSidney Mintz's Caribbean - ScottPeter ScheiffeleNo ratings yet

- The Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicDocument14 pagesThe Making of The Maori - Culture Invention and Its LogicCarola LalalaNo ratings yet

- The Gun and The Bow Stephen Hugh JonesDocument19 pagesThe Gun and The Bow Stephen Hugh Jonesestevaofernandes100% (1)

- Exploring The Indus Valley Civilization in India: ArticleDocument55 pagesExploring The Indus Valley Civilization in India: Articleaparna joshiNo ratings yet

- 10 2307539633-3Document13 pages10 2307539633-3Vanessa PironatoNo ratings yet

- Habermas Sobreparsons PDFDocument25 pagesHabermas Sobreparsons PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Bibliografia Criminologia PDFDocument10 pagesBibliografia Criminologia PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Otherton PDFDocument27 pagesOtherton PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Sutherlad Resenha LadrãoprofissionalDocument4 pagesSutherlad Resenha LadrãoprofissionalMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Selfcontroltheory LawandeconomicsDocument32 pagesSelfcontroltheory LawandeconomicsMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- CRIMINALJUSTICE Enemypenology PDFDocument26 pagesCRIMINALJUSTICE Enemypenology PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Chicago Durkheim Conections PDFDocument18 pagesChicago Durkheim Conections PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- ThreeStrikes Investigation CaliforniaDocument27 pagesThreeStrikes Investigation CaliforniaMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Blumer Prision PDFDocument4 pagesBlumer Prision PDFMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Whitecollarcrime TodayDocument19 pagesWhitecollarcrime TodayMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- So What - CrimDocument23 pagesSo What - CrimMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Criminology European Journal Of: The 'Surveillance Society': Questions of History, Place and CultureDocument17 pagesCriminology European Journal Of: The 'Surveillance Society': Questions of History, Place and CultureMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Merton Culturalincorporation SociologicalknowledgeDocument26 pagesMerton Culturalincorporation SociologicalknowledgeMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Conformity in American Society Today: by Lloyd E. OhlinDocument10 pagesConformity in American Society Today: by Lloyd E. OhlinMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Ross Edward SociologyDocument5 pagesRoss Edward SociologyMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Feminist Criminology Latinamerica ActivismDocument25 pagesFeminist Criminology Latinamerica ActivismMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Punishment & Society: Restorative Justice: The Real StoryDocument26 pagesPunishment & Society: Restorative Justice: The Real StoryMarcelo Sampaio100% (1)

- Research Note: The Impact of The "New Penology" On IspDocument13 pagesResearch Note: The Impact of The "New Penology" On IspMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Garland PunishmentDocument15 pagesGarland PunishmentMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Criminology: The Maximizer: Clarifying Merton's Theories of Anomie and StrainDocument22 pagesTheoretical Criminology: The Maximizer: Clarifying Merton's Theories of Anomie and StrainMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Merton BureaucraticstructureandpersonalityDocument10 pagesMerton BureaucraticstructureandpersonalityMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Myth of PunitivenessDocument28 pagesMyth of PunitivenessMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Merton AboutparsonsDocument13 pagesMerton AboutparsonsMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Academy of Political and Social The ANNALS of The American: Feminism in Criminology: Engendering The OutlawDocument21 pagesAcademy of Political and Social The ANNALS of The American: Feminism in Criminology: Engendering The OutlawMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Justice Criminology and Criminal: 'Criminal Man' The Rise of Biocriminology: Capturing Observable Bodily Economies ofDocument26 pagesJustice Criminology and Criminal: 'Criminal Man' The Rise of Biocriminology: Capturing Observable Bodily Economies ofMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- OthertonDocument27 pagesOthertonMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Talcon Parsons: Problems of Theory Construction: Juergen HabermasDocument25 pagesTalcon Parsons: Problems of Theory Construction: Juergen HabermasMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Criminology: New Directions in Cultural CriminologyDocument11 pagesTheoretical Criminology: New Directions in Cultural CriminologyMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- ItishDocument37 pagesItishMarcelo SampaioNo ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives 1Document36 pagesSociological Perspectives 1andremikhailNo ratings yet

- All Sophomore Classes Sociology 2021Document319 pagesAll Sophomore Classes Sociology 2021Mona A HassanNo ratings yet

- The Pragmatics of InteractionDocument277 pagesThe Pragmatics of InteractionValentina Espinoza DiazNo ratings yet

- Darrin M. McMahon, Samuel Moyn - Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History-Oxford University Press (2014) PDFDocument318 pagesDarrin M. McMahon, Samuel Moyn - Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History-Oxford University Press (2014) PDFWendel Antunes Cintra100% (2)

- McCracken Week 4Document10 pagesMcCracken Week 4leamurjeanNo ratings yet

- Marshall, T. H. - Citizenship and Social Class, and Other Essays (Cap. 1) PDFDocument47 pagesMarshall, T. H. - Citizenship and Social Class, and Other Essays (Cap. 1) PDFpedrorojas1No ratings yet

- Oc Courts Judges PhonesDocument10 pagesOc Courts Judges PhonesSteven SchoferNo ratings yet

- Sutherland - Populism and SpectaclerDocument17 pagesSutherland - Populism and Spectaclertjohns56No ratings yet

- SOC 113 Course OutlineDocument2 pagesSOC 113 Course OutlineHM6169003No ratings yet

- Language and Society SeminarDocument28 pagesLanguage and Society Seminarsiham100% (2)

- The Post-Industrial SocietyDocument132 pagesThe Post-Industrial SocietyIoana Stanciu100% (1)

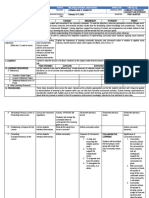

- DLL - Community Engagement SC - Quarter 1Document16 pagesDLL - Community Engagement SC - Quarter 1Von Judiel MacaraegNo ratings yet

- Das Leben Einer Frau in Der Mittelalterl PDFDocument339 pagesDas Leben Einer Frau in Der Mittelalterl PDFaudubelaiaNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag ARSP: Archiv Für Rechts-Und Sozialphilosophie / Archives For Philosophy of Law and Social PhilosophyDocument21 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag ARSP: Archiv Für Rechts-Und Sozialphilosophie / Archives For Philosophy of Law and Social PhilosophyAniss1296No ratings yet

- 307K Rehabilitation of Criminals & JuvenilesDocument81 pages307K Rehabilitation of Criminals & Juvenilesbhatt.net.in75% (4)

- Tonkiss - The Ethics of Indifference Community and Solitude in The CityDocument16 pagesTonkiss - The Ethics of Indifference Community and Solitude in The CityJoshua MontañoNo ratings yet

- Critical Approaches to Visual CultureDocument76 pagesCritical Approaches to Visual CultureRamón Salas100% (1)

- What Is The Phenomenological ApproachDocument15 pagesWhat Is The Phenomenological ApproachFiratNo ratings yet

- 2002 - PrasadDocument8 pages2002 - PrasadDebbie.Jones.VNo ratings yet

- Urbanism Theories and the Blasé OutlookDocument12 pagesUrbanism Theories and the Blasé OutlookAwista ImranNo ratings yet

- Sociology SummaryDocument13 pagesSociology SummaryRosa KavaldzhievaNo ratings yet

- From The Habitus To An Individual Heritage B. LahireDocument27 pagesFrom The Habitus To An Individual Heritage B. LahireCelso MendesNo ratings yet

- The Bystander Effect and The Evil of InactionDocument2 pagesThe Bystander Effect and The Evil of InactiontemplarknightxNo ratings yet

- Della Porta - Diani - The Oxford Handbook of Social MovementsDocument820 pagesDella Porta - Diani - The Oxford Handbook of Social MovementsDaniela Rojas HermidaNo ratings yet

- Completed Sociology IA111Document31 pagesCompleted Sociology IA111KemonaFacey100% (6)

- MacSwan and McAlister 2010 Natural and Elicited Data in Grammatical Studies of CodeswitchingDocument12 pagesMacSwan and McAlister 2010 Natural and Elicited Data in Grammatical Studies of CodeswitchingwudzielaNo ratings yet

- Marriage and the Construction of RealityDocument13 pagesMarriage and the Construction of RealityAle_8702No ratings yet

- Theory and Research in The Sociology of EducationDocument19 pagesTheory and Research in The Sociology of Educationbolindro100% (3)

- Critical Discourse Analysis: Demystifying The Fuzziness: October 2015Document9 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis: Demystifying The Fuzziness: October 2015fetty WahyuningrumNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Approaches in The History of Ethno MusicologyDocument37 pagesPhenomenological Approaches in The History of Ethno MusicologyJulián Castro-CifuentesNo ratings yet