Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MRC v. Hunter - Opp'n To Cert. Pet.

Uploaded by

Sarah BursteinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MRC v. Hunter - Opp'n To Cert. Pet.

Uploaded by

Sarah BursteinCopyright:

Available Formats

No.

14-5

THE LEX GROUP

DC

1825 K Street, N.W. Suite 103 Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 955-0001 (800) 856-4419 Fax: (202) 955-0022 www.thelexgroup.com

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

-------------------------- ---------------------------

MRC INNOVATIONS, INC.,

Petitioner,

v.

HUNTER MFG., LLP, and

CDI INTERNATIONAL, INC.,

Respondents.

-------------------------- --------------------------

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

-------------------------- --------------------------

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

-------------------------- --------------------------

Perry J. Saidman

Counsel of Record

SAIDMAN DESIGNLAW GROUP, LLC

8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 603

Silver Spring, Maryland 20910

(301) 585-8601

perry.saidman@designlawgroup.com

Edward D. Manzo Andrew D. Dorisio

Mark J. Murphy Trevor T. Graves

HUSCH BLACKWELL LLP KING & SCHICKLI, PLLC

120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2200 247 N. Broadway

Chicago, Illinois 60606 Lexington, Kentucky 40507

(312) 655-1500 (859) 252-0889

edward.manzo@huschblackwell.com andrew@iplaw1.net

mark.murphy@huschblackwell.com trevor@iplaw1.net

Counsel for Respondents Dated: August 27, 2014

i

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Petitioner presented compelling

reasons for this Court to grant certiorari and review

a well-reasoned decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the Federal Circuit (Court of Appeals) affirming

the district courts summary judgment finding two

design patents invalid through an established

obviousness framework that is consonant with KSR

Intl Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 415 (2007)

such that the Court of Appeals decision does not

implicate an important federal question in a way

that conflicts with relevant decisions of this Court or

the Court of Appeals.

ii

RULE 29.6 STATEMENT

Respondents have no parent corporations and

no publicly held company owns 10% or more of its

stock.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED .......................................... i

RULE 29.6 STATEMENT .......................................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................ iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... iv

INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................... 4

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION ........... 8

1. Petitioner Glosses Over the Fact

that Design Patents are

Fundamentally Different than

Utility Patents ....................................... 8

2. Based on Similarity in Appearance,

the So Related Standard

Comports with the Visual Nature

of Designs and the Flexible

Approach Advanced by KSR ................13

3. The Far-Reaching Negative

Effects of Denying Review are

Illusory ..................................................20

CONCLUSION ......................................................... 21

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

CASES

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co.,

678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ...................... 11

Dobson v. Dornan,

118 U.S. 10 (1886) ............................................ 9

Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co.,

101 F.3d 100 (Fed. Cir. 1996) ........................ 11

Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc.,

543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008) .................... 9, 19

High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc.,

730 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2013) ...................... 11

In re Borden,

90 F.3d 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1996) .................. 10, 18

In re Glavas,

230 F.2d 447 (C.C.P.A. 1956) ...... 11, 12, 18, 20

In re Harvey,

12 F.3d 1061 (Fed. Cir. 1993) ........................ 11

In re Kahn,

441 F.3d 977 (Fed. Cir. 2006) .................. 15, 16

In re Rosen,

673 F.2d 388 (C.C.P.A. 1982) .................. 10, 12

v

KSR Intl Co. v. Teleflex, Inc.,

550 U.S. 398 (2007) ................................ passim

Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc.,

566 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2009) ........................ 2

MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter MFG, LLP,

921 F. Supp. 2d 800

(N.D. Ohio 2013) .............................. 3, 7, 17, 19

MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter MFG, LLP,

747 F.3d 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2014) .................. 8, 13

STATUTES

35 U.S.C. 101 ........................................................ 1, 8

35 U.S.C. 103 .................................................... 10, 20

35 U.S.C. 103(a) ....................................................... 7

35 U.S.C. 171 ........................................................ 1, 8

RULE

Sup Ct. R. 10 ............................................................... 1

REGULATION

37 C.F.R. 1.153 ......................................................... 9

vi

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Prof. Janice M. Mueller and Daniel Brean,

Overcoming the Impossible Issue of

Nonobviousness in Design Patents, Legal

Studies Research Paper Series, Working Paper

No. 2009-30, University of Pittsburgh School of

Law, November, 2009 .................................................. 8

Manual of Patent Examining Procedure .................. 21

1

INTRODUCTION

Petitioner presents no compelling reasons

for granting its Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

(Petition). See Sup Ct. R. 10. The decisions below

apply a longstanding design patent obviousness test

that accords with this Courts decision in KSR Intl

Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007). Petitioner

is mistaken to argue otherwise, and is mistaken that

review is necessary to ameliorate far-reaching

negative effects, which Petitioner fails to

substantiate. Therefore, the Petition should be

denied.

Petitioner contends that more than sixty years

of design patent jurisprudence on the issue of

obviousness and the decisions below conflict with

this Courts holding in KSR. Petitioner complains

that the longstanding so related test for combining

known prior art designs to render a design patent

obvious is too loose and therefore somehow at odds

with the flexible approach required by KSR in

connection with combining known elements in

analyzing the obviousness of a utility patent.

Respondent submits that there is no conflict at all

finding and articulating that two designs are so

related based on their overall appearance comports

with KSR, and is entirely consistent with this

Courts and lower courts design patent

jurisprudence.

KSR involved a utility patent (governed by 35

U.S.C. 101), which is fundamentally different than

a design patent (governed by 35 U.S.C. 171),

which is involved in the present case. KSR expressly

2

rejected any rigidly applied standard to the analysis

of obviousness, such as the teaching, suggestion, or

motivation, or TSM, test that had become prevalent

in utility patent obviousness analysis. KSR at 415,

418-421. This Court recognized the need to remain

flexible in the obviousness analysis and consider

other factors, such as whether market forces might

prompt a skilled artisan to vary a prior art approach

in a manner that would fail to create a patentable

improvement. Id. at 417. This Court particularly

emphasized the need for caution in granting a

patent based on the combination of elements found

in the prior art. Id. at 415. The overly stringent

obviousness analysis of utility patents that gave rise

to KSR does not occur in the design patent

obviousness framework, which is based not on a

textual analysis but a visual comparison.

Assuming the intent of KSR applies to the

analysis of obviousness of a design patent (this Court

made no explicit reference to design patents in

KSR)

1

, its expansive and flexible approach is already

imbued in the design patent standard for combining

two references and was in fact followed here by the

lower courts, which thoroughly discussed and

1

The Court of Appeals has cited KSR in just one design patent

decision, saying that this Court did not necessarily intend to

exclude design patents from the reach of KSR. Titan Tire

Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1384 (Fed. Cir.

2009). The application of KSR to design patents has not been

more explicitly considered because it hasnt been necessary

the design patent so related test for combining secondary

references comports with KSRs mandate of a flexible approach.

KSR addressed an overly rigid obviousness framework that was

being applied in utility patents which has not been the case

with design patents.

3

ultimately found that the prior art pet jersey designs

at issue are so related in visual appearance to

warrant their combination. Indeed, it cannot be

disputed that the district court expressly articulated

its reasoning, observing and characterizing the

designs, then concluding that because the prior art

designs at issue are so related to one another in

appearance that it is not a matter of extraordinary

skill to combine their features. See MRC

Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter MFG, LLP, 921 F. Supp.

2d 800, 809 (N.D. Ohio 2013). Accordingly, the lower

court fully complied with the spirit of KSR by

providing an articulation supporting the legal

conclusion of obviousness.

Dissatisfied that its design patents stand

invalid on prevailing law, Petitioner seeks to lower

the standards for patentability. This Court should

decline Petitioners suggestion to harken back to a

time when the failure to say some magic words or

otherwise meet some rigid standard too easily

precluded obviousness. The flexibility promoted by

KSR does not allow this, and there is no reason for

this Court to inject a rigid analysis into the

obviousness framework for design patents, which,

although fundamentally different than utility

patents, are governed by the same statutory

requirements for obviousness. The threat of some

unspecific future harm that may result from more

design patents claiming combinations of known

elements being invalidated as obvious is likewise not

a reason for upending sixty years of precedent and

the resultant settled expectations of the design

patent community.

4

For the foregoing reasons, review by this

Court is both unnecessary and unwarranted in view

of the carefully considered, well-reasoned decisions

rendered in this matter, which are consistent with

all applicable precedent. As the Petitioner has

completely failed to carry its burden of

demonstrating that there are any compelling reasons

to grant the Petition, it should be denied.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondent Hunter Mfg., LLP (Hunter) is a

retailer of licensed sports consumer products, and

has sold pet jerseys since at least as early as 2006,

typically in connection with licensed material such

as NFL or MLB logos.

Petitioner MRC Innovations, Inc. (MRC) is

the owner by assignment of both patents in suit.

The 488 patent claims an ornamental design for a

football jersey for a dog, while the 487 patent does

the same for a baseball jersey.

Mark Cohen is the named inventor of both

patents; he is the principal shareholder of MRC and

assigned his rights in both patents to that company.

Prior to the issuance of the patents in suit, Hunter

purchased pet jerseys for dogs from Mark Cohen

through various companies with which he was

affiliated. Among others, Cohen supplied Hunter

with a V2 football jersey and a green pet jersey

bearing a Philadelphia Eagles logo, which Hunter

then sold through third-party retailers. The prior

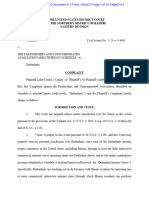

art V2 and Eagles jerseys are depicted below next to

the 488 patent:

5

Cohen asserts that in 2009 he designed

another pet jersey, known as the V3 jersey, which

would later become the subject of the 488 patent.

Hunter began purchasing the V3 jersey from one of

Cohens affiliated companies. Later Cohen filed a

patent application for both the V3 jersey and the

baseball equivalent that would later become the

subject of the 487 patent. In late 2010, the business

relationship between Cohen and Hunter ended.

Hunter then sought proposals from other companies

488 Patent V2 Jersey Eagles Jersey

6

to manufacture and supply it with pet jerseys like

the V3. Ultimately, Hunter contracted with another

supplier, Co-Respondent CDI, to supply Hunter with

pet jerseys.

Both patents-in-suit eventually issued on

March 15, 2011. MRC filed suit against both Hunter

and CDI for willful infringement of both patents.

Regarding the 487 patent, Hunter through

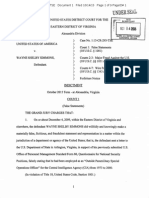

discovery identified a prior art pet baseball jersey

known as the Sporty K9 baseball jersey.

487 Patent Sporty K9 Baseball

Jersey

7

The district court granted summary judgment

in favor of Hunter and CDI on the grounds that both

patents are invalid as obvious under 35 U.S.C.

103(a) based on the prior art V2, Eagles and

Sporty K9 pet football jerseys. MRC Innovations at

809.

The district court issued a well-reasoned

opinion holding the Eagles and V2 jerseys to be

basically the same as the design claimed in the

488 Patent. The district court also agreed that the

V2 and Eagles jerseys (which are both pet football

jerseys just like the article claimed in the 488

Patent), were so related in appearance as to

suggest the application of the ornamental features of

one to the other. The 487 Patent was also held

invalid based on the Sporty K9 baseball jersey, due

to its striking similarities and despite the existence

of unremarkable differences. The Court of Appeals

then affirmed the entry of summary judgment in all

8

respects. MRC Innovations, Inc. v. Hunter MFG,

LLP, 747 F.3d 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2014).

REASONS TO DENY THE PETITION

1. Petitioner Glosses Over the Fact that

Design Patents are Fundamentally

Different than Utility Patents

A design patent is granted for any new,

original and ornamental design of an article of

manufacture, 35 U.S.C. 171, while a utility patent

is granted for any new and useful process, machine,

manufacture, or composition of matter, 35 U.S.C.

101. A design patent protects the appearance of a

product without regard to how it works, and a utility

patent protects how a product works or functions

without regard to its appearance.

Thus, the subject matter of a design patent

the appearance of a product is fundamentally

different than a utility patent the way a product

works or functions.

2

A design patent is bereft of a

2

Indeed, commentators have questioned whether KSR, directed

to mechanical, utility patent inventions, would be appropriate

to apply to determining design patent obviousness. See, e.g.,

Prof. Janice M. Mueller and Daniel Brean, Overcoming the

Impossible Issue of Nonobviousness in Design Patents, Legal

Studies Research Paper Series, Working Paper No. 2009-30,

University of Pittsburgh School of Law, November, 2009

(Courts should be cautious in automatically applying the

specific holdings of KSR to designs. Most of the KSR Courts

discussion is completely irrelevant to what design patents

protect the ornamental appearance of an article of

manufacture, considered as a whole, not as a combination of its

individual features or the manner by which the articles design

was achieved.)

9

detailed verbal description of the claimed design,

while a utility patent specification is largely, if not

exclusively, comprised of written description. A

design patent consists almost entirely of drawings

showing how the product looks; a utility patent

includes a detailed description of how the product

functions and the metes and bounds of its claims are

interpreted in view of the detailed description of how

the invention works.

On the other hand, a design patent is

permitted only a single claim, which is required to be

in a standard format, to wit: The ornamental

design for [the article which embodies the design],

as shown and described. 37 C.F.R. 1.153. The

referenced description is either a perfunctory

description of the figures (e.g., FIG. 1 is a

perspective view; FIG. 2 is a side view; and the like)

or is very limited. Thus, the metes and bounds of a

design patent claim are defined by the drawings. It

is widely recognized that design patent drawings

provide a much better representation of a design

than words could possibly express.

3

3

In Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 679

(Fed. Cir. 2008) the Court of Appeals noted: As the Supreme

Court has recognized, a design is better represented by an

illustration than it could be by any description and a

description would probably not be intelligible without the

illustration. Dobson v. Dornan, 118 U.S. 10, 14 (1886).

10

Due to this fundamental difference in

patentable subject matter, and even though [d]esign

patents are subject to the same conditions on

patentability as utility patents, including the

nonobviousness requirement . . . . In re Borden, 90

F.3d 1570, 1574 (Fed. Cir. 1996), of necessity the

obviousness of a design patent and a utility patent

are analyzed within different frameworks.

Accordingly, for design patents, obviousness

analysis must focus of what the designs in question

look like. The jurisprudence in determining when

the appearance of a claimed design is obvious in

view of the prior art is well established.

Determining design patent obviousness rightly has a

framework tailored to the question of whether the

appearance of a product would have been obvious to

a person of ordinary skill, i.e., an ordinary designer,

within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. 103. Following is

a brief summary of that case law.

When assessing the potential obviousness of a

design, and before combining prior art references,

the finder of fact must first find a single primary

reference, a something in existence, the design

characteristics of which are basically the same as the

claimed design, In re Rosen, 673 F.2d 388 (C.C.P.A.

1982). Without such a primary reference, it is

improper to invalidate a design patent on grounds of

obviousness, Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101

F.3d 100, 103-04 (Fed. Cir. 1996).

11

Once a proper primary reference is found,

secondary references may be used to modify the

primary reference to create a design that has the

same overall visual appearance as the patented

design, provided that the primary and secondary

references are so related that the appearance of

certain ornamental features in one would suggest

the application of those features to the other. In re

Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (C.C.P.A. 1956) (emphasis

added). See also Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co.,

678 F.3d 1314, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2012); High Point

Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc., 730 F.3d

1301,1311 (Fed. Cir. 2013). In this context, so

related means related in visual appearances, not in

design concepts, In re Harvey, 12 F.3d 1061, 1064

(Fed. Cir. 1993).

The so-related test central to this case was

first enunciated in Glavas, supra, which involved a

claimed design for a swimming float. The prior art

included an earlier design for a float (the primary

reference), and also the design of disparate articles

such as bottles, soap and razor blade sharpeners (the

secondary references). Examining the issue of

whether such non-float secondary references could

be relevant to a determination of obviousness, the

court recognized that the nature of ornamental

designs is different from functional inventions:

A design, from the standpoint of

patentability, has no utility other than

its ornamental appearance, and the

12

problem of combining references is

therefore one of the combining

appearances rather than uses. The

principle of non-analogous arts,

therefore, cannot be applied to design

cases in exactly the same manner as

to mechanical cases. The question in

design cases is not whether the

references sought to be combined are

in analogous arts in the mechanical

sense, but whether they are so related

that the appearance of certain

ornamental features in one would

suggest the application of those

features to the other. Id.

This so related test in Glavas led to a finding

that the [non-float] articles and their shapes are of

such a nature that they would not, in our opinion,

suggest the modification to the appearance of a

traditional float. Id.

Later, Rosen, while reiterating the holding of

Glavas, added a requirement that before any

combination of the prior art can occur, there must

be a reference, a something in existence, the design

characteristics of which are basically the same as the

claimed design in order to support a holding of

obviousness. Rosen, supra at 391. This additional

requirement of identifying a primary reference

prevents myriad features from unrelated articles

being used to create a similar design from whole

cloth, and applies whether the design patent

obviousness question relies on one or many

references. It guards against arbitrary or

13

unwarranted holdings of design patent obviousness,

and also helps a reviewing court establish the

propriety of a lower courts finding of design patent

obviousness.

The decisions of the lower courts in this case

adhered to this established framework. Specifically,

the district court found a single reference, a

something in existence, the design characteristics of

which are basically the same as the claimed design

(or stated another way, a primary reference for the

pet jerseys illustrated in the 487 and 488 Patents).

For the 488 Patent, it also found a secondary prior

art design so related to suggest the application of its

visual features to those of the primary reference. As

the Court of Appeals below expressly noted in

affirming the finding of obviousness, the secondary

references that the district court relied on were not

furniture, or drapes, or dresses, or even human

football jerseys; they were football jerseys designed

to be worn by dogs just the same as the claimed

jersey in the 488 Patent. MRC Innovations, 747

F.3d at 1332. It cannot be disputed that the analysis

of the situation was made explicit, with the lower

court explaining in detail why the patents at issue

were invalid as obvious in view of the prior art.

2. Based on Similarity in Appearance, the

So Related Standard Comports with

the Visual Nature of Designs and the

Flexible Approach Advanced by KSR

The Petitioners request for review is based on

a single, flawed premise that the Court of Appeals

framework for design patent obviousness analysis is

14

inconsistent with KSR. Petitioner argues that the

so related test for combining prior art designs is

too loose (Petitioner brief at 19-20), and does not

sufficiently articulate a rational basis for selecting

and combining features found in prior art design

references.

Respondent submits that the so related test

provides exactly the explicit rational basis embraced

by KSR, the overall thrust of which favors flexibility

in obviousness analysis, rather than require a rigid

detailed explanation. Petitioner calls for a degree of

explanation for combining references that was

rejected in KSR.

Petitioner repeatedly states that KSR requires

an explicit analysis regarding whether there was an

apparent reason to combine the known elements in

the fashion claimed by the patent. Petitioner alleges

that the Court of Appeals longstanding so related

test eliminates the requirement for a reason to

combine references and allows courts to presume

obviousness where elements of a claimed design are

present in prior art references that are merely

related.

Petitioners arguments miss KSRs mark to

ensure that obviousness analysis is not confined by

a formalistic conception. KSR at 402.

To facilitate review on appeal, KSR does

support an explicit statement of an apparent reason

to combine known elements:

15

Often, it will be necessary for a court

to look to interrelated teachings of

multiple patents; the effects of

demands known to the design

community or present in the

marketplace; and the background

knowledge possessed by a person

having ordinary skill in the art, all in

order to determine whether there was

an apparent reason to combine the

known elements in the fashion claimed

by the patent at issue. To facilitate

review, this analysis should be made

explicit. See In re Kahn, 441 F.3d 977,

988 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ([R]ejections on

obviousness grounds cannot be

sustained by mere conclusory

statements; instead, there must be

some articulated reasoning with some

rational underpinning to support the

legal conclusion of obviousness). As

our precedents make clear, however,

the analysis need not seek out precise

teachings directed to the specific

subject matter of the challenged claim,

for a court can take account of the

inferences and creative steps that a

person of ordinary skill in the art

would employ. KSR at 418.

Plainly, in stating this analysis should be

made explicit KSR meant to make sure the record

provides reasoning reviewable on appeal, and not

simply a conclusory finding of obviousness without a

clear, articulated basis for the finding. In full

16

context, explicit does not mandate an enunciation

of why it would be obvious to select specific features

and combine them in the particular manner claimed.

KSR notes that in many fields, there is little

discussion of obvious combinations. Id. at 419. This

is exactly the case with designs.

In the context of designs, the inferences and

creative steps courts can take into account are

subsumed in the analysis that results in a courts

determination of whether or not the visual features

in prior art references are so related that they may

be combined.

The Court of Appeals design patent

obviousness framework provides the requisite

articulation and underpinning, allowing the

combination of visual design features from prior art

references when a court reviews them and

determines they are so related such that the

appearance of ornamental features in one design

would suggest their application to the other.

A courts finding that two design references

are so related to support a combination of their

design features is not the mere conclusory statement

with which Kahn was concerned; it is a

determination that follows from the type of analysis

apposite for designs based on visual appearance,

not extensive written descriptions as is the norm in

utility patent obviousness analysis. A courts

determination that references are visually so

related meets KSRs goals in articulating the

obviousness analysis.

17

In the case at bar, the Court of Appeals

thoroughly applied the so related test and

articulated its determination, noting not just

common subject matter, but also a striking

similarity in appearance among the prior art

references that would have motivated a skilled

designer to combine features from one with features

of the other:

After concluding that the Eagles

jersey could be a primary reference,

the district court determined that the

V2 jersey and another reference

known as the Sporty K9 jersey were

so related to the primary reference

that they could serve as secondary

references that would motivate the

skilled artisan to make the claimed

design. MRC, 921 F. Supp. 2d at 809.

The district court found that both

jerseys suggested the use of a V-neck

pattern and non-mesh fabric on the

side panelsthe first two differences

described above. MRC argues that the

district court erred by failing to

explain why a skilled artisan would

have chosen to incorporate those

features of the V2 and Sporty K9

jerseys with the Eagles jersey.

We disagree. It is true that [i]n order

for secondary references to be

considered, ... there must be some

suggestion in the prior art to modify

18

the basic design with features from

the secondary references. In re

Borden, 90 F.3d at 1574. However, we

have explained this requirement to

mean that the teachings of prior art

designs may be combined only when

the designs are so related that the

appearance of certain ornamental

features in one would suggest the

application of those features to the

other. Id. at 1575 (quoting In re

Glavas, 43 CCPA 797, 230 F.2d 447,

450 (1956)). In other words, it is the

mere similarity in appearance that

itself provides the suggestion that one

should apply certain features to

another design.

So too, here, the secondary references

that the district court relied on were

not furniture, or drapes, or dresses, or

even human football jerseys; they

were football jerseys designed to be

worn by dogs. Moreover, as discussed

above, the V2 could easily have served

as a primary reference itself, so

similar is its overall visual appearance

to that of the claimed design and the

Eagles jersey. See supra n.3. We

therefore agree that those references

were so related to the Eagles jersey

that the striking similarity in

appearance across all three jerseys

19

would have motivated a skilled

designer to combine features from one

with features of another.

MRC Innovations at 1334-35.

This explicit articulation, based upon the

appearance of the designs, memorializes the courts

rationale to combine them. Requiring further

specific explanation as to why a person of ordinary

skill in the art would have incorporated some, but

not all, features (Petitioners brief at 17) of the

secondary references contradicts the flexible

approach directed by KSR.

The Petition falsely asserts that the so

related test usurps obviousness for relatedness.

(Petitioner brief at 20.) Relatedness in and of itself

does not permit combination of prior art designs;

whether designs are so related that they can be

combined is based on a judgment of similarity in

appearance, not merely a threshold similarity based

on the type of underlying article.

Petitioner calls for a detailed explanation for

why the skilled designer would have found it obvious

to make the particular selections of design features

and combine them. Such detailed explanation is

inconsistent with sound design patent jurisprudence,

which generally recognizes that the appearance of

the designs provide their own best description

4

, and

pushes beyond the requirements of KSR for the

purpose of review on appeal into the territory

criticized by KSR as too narrow for analysis of the

4

See Egyptian Goddess, n. 3, supra.

20

obviousness inquiry. For these reasons, the Petition

should be denied.

3. The Alleged Far-Reaching Negative

Effects of Denying Review are Illusory

Petitioners argument that the Court of

Appeals decision if allowed to stand will have far-

reaching negative effects is also not a reason to

grant the Petition. As noted above, the so related

test first appeared shortly after the inception of the

modern U.S. Patent Act, Glavas, supra, and it has

been properly followed by the lower courts for more

than sixty years, including in this case. Industries

that obtain design patent protection have come to

rely on this established, stable design patent

obviousness framework.

In its dire warning of purported negative

effects, Petitioner simply recycles its central theme,

arguing once again that under the present design

patent obviousness standard too many design

patents may be declared invalid because the courts

are not required to provide an explicit analysis of

whether there was a reason to combine the known

elements in the fashion claimed by the patent. As

noted above, this argument is without merit.

Petitioner further contends that the so

related test conflicts with this Courts prior case law

regarding 35 U.S.C. 103, is unreasonable, and

put[s] the validity of many issued design patents in

jeopardy. (Petitioner brief at 6).

It is unclear how

the validity of issued patents is in jeopardy as a

result of this test, given that it is the exact one

21

applied by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in

analyzing obviousness before granting a patent. See

the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure at

1504.03 (The long-standing test for properly

combining references has been ...whether they are so

related that the appearance of certain ornamental

features in one would suggest the application of

those features to the other.). This test did not stop

the issuance of the 488 Patent here because

astonishingly Mr. Cohen failed to disclose his own

prior art V2 and Eagles designs to the Patent Office.

Petitioners suggestion that creating a more

rigorous standard for combining references than the

purportedly too loose test currently applied would

avoid some unspecified negative effects should be

read with caution, especially since no proof is offered

as to how a reworked standard would ameliorate

some unspecified future harm. Granting design

patent protection for predictable design variations

will not serve the fundamental purpose of the patent

laws of fostering innovation.

CONCLUSION

Petitioners have not established any

compelling reasons for this Court to grant the

Petition. Accordingly, it is respectfully submitted

that the Petition for Writ of Certiorari should be

denied.

22

Respectfully submitted,

Perry J. Saidman

Counsel of Record

SAIDMAN DESIGNLAW GROUP, LLC

8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 603

Silver Spring, Maryland 20910

Telephone: (301) 585-8601

Facsimile: (301) 585-0138

perry.saidman@designlawgroup.com

Edward D. Manzo

Mark J. Murphy

HUSCH BLACKWELL LLP

120 South Riverside Plaza, Suite 2200

Chicago, Illinois 60606

Telephone: (312) 655-1500

Facsimile: (312) 655-1501

edward.manzo@huschblackwell.com

mark.murphy@huschblackwell.com

Andrew D. Dorisio

Trevor T. Graves

KING & SCHICKLI, PLLC

247 N. Broadway

Lexington, Kentucky 40507

Telephone: (859) 252-0889

Facsimile: (859) 252-0779

andrew@iplaw1.net

trevor@iplaw1.net

Counsel for Respondents

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- AJ's Nifty Prods. v. Schedule A (23-cv-14200) - PI Opp'nDocument12 pagesAJ's Nifty Prods. v. Schedule A (23-cv-14200) - PI Opp'nSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- UATP v. Kangaroo - Brief ISO PIDocument91 pagesUATP v. Kangaroo - Brief ISO PISarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Viniello v. Target - ComplaintDocument62 pagesViniello v. Target - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Blue Spring v. Schedule A - ComplaintDocument28 pagesBlue Spring v. Schedule A - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Wang v. Schedule A - TRO BriefDocument33 pagesWang v. Schedule A - TRO BriefSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Smarttrend v. Optiluxx - Renewed Motion For JMOLDocument34 pagesSmarttrend v. Optiluxx - Renewed Motion For JMOLSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Keller v. Spirit Halloween - ComplaintDocument17 pagesKeller v. Spirit Halloween - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Kyjen v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-15119) - Motion To StrikeDocument3 pagesKyjen v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-15119) - Motion To StrikeSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- ABC v. Schedule A (23-cv-04131) - Order On Preliminary Injunction (Ending Asset Freeze)Document12 pagesABC v. Schedule A (23-cv-04131) - Order On Preliminary Injunction (Ending Asset Freeze)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Roblox v. Schedule A - Order Sanctioning PlaintiffDocument5 pagesRoblox v. Schedule A - Order Sanctioning PlaintiffSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Rockbros v. Shehadeh - ComplaintDocument11 pagesRockbros v. Shehadeh - ComplaintSarah Burstein100% (1)

- Wearable Shoe Tree v. Schedule A - Hefei XunTi OppositionDocument20 pagesWearable Shoe Tree v. Schedule A - Hefei XunTi OppositionSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Cixi City v. Yita - ComplaintDocument23 pagesCixi City v. Yita - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- XYZ (Pickle Jar) v. Schedule A - Order Denying MTD As MootDocument2 pagesXYZ (Pickle Jar) v. Schedule A - Order Denying MTD As MootSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- TOB (1:23-cv-01563) - Motion To DissolveDocument20 pagesTOB (1:23-cv-01563) - Motion To DissolveSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Combs v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-14485) - ComplaintDocument99 pagesCombs v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-14485) - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Sport Dimension v. Schedule A - Webelar MTDDocument28 pagesSport Dimension v. Schedule A - Webelar MTDSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Mobile Pixels v. Schedule A - Complaint (D. Mass.)Document156 pagesMobile Pixels v. Schedule A - Complaint (D. Mass.)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Betty's Best v. Schedule A - RNR Re PIDocument21 pagesBetty's Best v. Schedule A - RNR Re PISarah Burstein100% (1)

- Thousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - DP & UP ComplaintDocument32 pagesThousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - DP & UP ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Chrome Hearts - Motion For TRODocument17 pagesChrome Hearts - Motion For TROSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Hong Kong Xingtai v. Schedule A - Memo Re JoinderDocument5 pagesHong Kong Xingtai v. Schedule A - Memo Re JoinderSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Kohler v. Signature - ComplaintDocument27 pagesKohler v. Signature - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Thousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - UP ComplaintDocument57 pagesThousand Oaks Barrel v. Schedule A (EDVA) - UP ComplaintSarah Burstein100% (1)

- BB v. Schedule A - ComplaintDocument28 pagesBB v. Schedule A - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Ridge v. Kirk - ComplaintDocument210 pagesRidge v. Kirk - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- BTL v. Schedule A - Exhibit 11 To PI Opposition (132-11)Document4 pagesBTL v. Schedule A - Exhibit 11 To PI Opposition (132-11)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Wright v. Dorsey - ResponsesDocument94 pagesWright v. Dorsey - ResponsesSarah Burstein100% (1)

- Steel City v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-06993) - ComplaintDocument10 pagesSteel City v. Schedule A (1:23-cv-06993) - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Pim v. Haribo - Decision (3d. Circuit)Document11 pagesPim v. Haribo - Decision (3d. Circuit)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- PEOPLE v. MUNARDocument2 pagesPEOPLE v. MUNARMichelle Vale CruzNo ratings yet

- LGST 101 Problems: Offer, Acceptance, ConsiderationDocument16 pagesLGST 101 Problems: Offer, Acceptance, ConsiderationKrishnan SethumadhavanNo ratings yet

- SuccesionDocument111 pagesSuccesionEnroNo ratings yet

- Josefa V BuenaventuraDocument8 pagesJosefa V BuenaventuraMADEE VILLANUEVANo ratings yet

- Murphy v. Ginorio, 1st Cir. (1993)Document13 pagesMurphy v. Ginorio, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Fletcher vs. DirectorDocument4 pagesFletcher vs. DirectorDean Epifanio EstrelladoNo ratings yet

- GUILLERMINA BALUYUT, Petitioner, Eulogio Poblete, Salud Poblete and The Hon - Court OF APPEALS, RespondentsDocument2 pagesGUILLERMINA BALUYUT, Petitioner, Eulogio Poblete, Salud Poblete and The Hon - Court OF APPEALS, Respondentschappy_leigh118No ratings yet

- Hormillosa Vs Coca ColaDocument13 pagesHormillosa Vs Coca ColaAJMordenoNo ratings yet

- US v. Simmons: Grand Jury IndictmentDocument9 pagesUS v. Simmons: Grand Jury IndictmentGrasswireNo ratings yet

- Northwest Airlines v. CADocument1 pageNorthwest Airlines v. CAphgmbNo ratings yet

- Belita vs. Sy G.R. No. 191087 June 2016Document14 pagesBelita vs. Sy G.R. No. 191087 June 2016Kesca GutierrezNo ratings yet

- 01-City of Manila v. Grecia-Cuerdo GR No 175723 PDFDocument11 pages01-City of Manila v. Grecia-Cuerdo GR No 175723 PDFryanmeinNo ratings yet

- Perla Research 2Document8 pagesPerla Research 2Jas Em BejNo ratings yet

- Legal Baller's Response To Disciplinary ChargesDocument12 pagesLegal Baller's Response To Disciplinary ChargesAnonymous 2NUafApcV100% (1)

- James Holmes Court Docs.Document163 pagesJames Holmes Court Docs.ChaebaiNo ratings yet

- Hasegawa Vs KitamuraDocument7 pagesHasegawa Vs KitamuraRv LacayNo ratings yet

- Husband Falsified Wife's Signature Exception to Marital DisqualificationDocument1 pageHusband Falsified Wife's Signature Exception to Marital Disqualificationchara escanoNo ratings yet

- Aleynikov v. Goldman Sachs OpinionDocument34 pagesAleynikov v. Goldman Sachs OpinionDealBookNo ratings yet

- Adez Realty v. CADocument5 pagesAdez Realty v. CAPrncssbblgmNo ratings yet

- Madras HC sets aside maintenance orderDocument3 pagesMadras HC sets aside maintenance orderPrasadNo ratings yet

- Malayan Law Journal Unreported/2009/Volume /Dorai Pandian a/l Munian and Anor v Pendakwa RayaDocument30 pagesMalayan Law Journal Unreported/2009/Volume /Dorai Pandian a/l Munian and Anor v Pendakwa RayaRazali ZlyNo ratings yet

- City of Manila Vs Chinese Com DigestDocument2 pagesCity of Manila Vs Chinese Com DigestVanityHugh100% (8)

- Essentials and Defences of DefamationDocument16 pagesEssentials and Defences of Defamationvaibhav vermaNo ratings yet

- Chesnel Forgue v. U.S. Attorney General, 401 F.3d 1282, 11th Cir. (2005)Document6 pagesChesnel Forgue v. U.S. Attorney General, 401 F.3d 1282, 11th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estate Settlement DisputeDocument231 pagesEstate Settlement Disputepit1xNo ratings yet

- FDocument44 pagesFTimmy HaliliNo ratings yet

- Efren S. Almuete, Petitioner, vs. People of The PHILIPPINES, RespondentDocument23 pagesEfren S. Almuete, Petitioner, vs. People of The PHILIPPINES, RespondentKevin DinsayNo ratings yet

- Cases CivProDocument276 pagesCases CivProOmar Jayson Siao VallejeraNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Malaysian Courts and Stay of ProceedingsDocument13 pagesJurisdiction of Malaysian Courts and Stay of ProceedingsSerzan HassnarNo ratings yet

- University of Cordilleras College of LawDocument60 pagesUniversity of Cordilleras College of LawCyrus DaitNo ratings yet