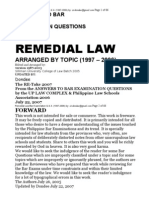

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Neypes Rule

Uploaded by

Eloisa Katrina Madamba0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

253 views6 pagesCivil Procedure, Motion For New Trial and Reconsideration

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCivil Procedure, Motion For New Trial and Reconsideration

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

253 views6 pagesThe Neypes Rule

Uploaded by

Eloisa Katrina MadambaCivil Procedure, Motion For New Trial and Reconsideration

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

The Neypes Rule

STATEMENT OF THE RULE

The "Neypes Rule," otherwise known as the Fresh Period Rule,

states that a party litigant may either file his notice of appeal within

15 days from receipt of the Regional Trial Courts decision or file it

within 15 days from receipt of the order (the "final order") denying his

motion for new trial or motion for reconsideration. (Domingo Neypes

versus Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 141524 September 14, 2005)

PURPOSE OF THE RULE

To standardize the appeal periods provided in the Rules and to afford

litigants fair opportunity to appeal their cases, the Court deems it

practical to allow a fresh period of 15 days within which to file the

notice of appeal in the Regional Trial Court, counted from receipt of

the order dismissing a motion for a new trial or motion for

reconsideration. (supra)

The raison dtre for the "fresh period rule" is to standardize the

appeal period provided in the Rules and do away with the confusion as

to when the 15-day appeal period should be counted. Thus, the 15-day

period to appeal is no longer interrupted by the filing of a motion for

new trial or motion for reconsideration; litigants today need not

concern themselves with counting the balance of the 15-day period to

appeal since the 15-day period is now counted from receipt of the

order dismissing a motion for new trial or motion for reconsideration or

any final order or resolution. (Judith Yu versus Hon. Rosa Samson-

Tatad, G.R. No. 170979, 09 Feb. 2011)

THE RULE PRIOR TO NEYPES

Before the Supreme Court prmulgated Neypes, the rules mandate that

the filing of a motion for reconsideration interrupts the running of the

period to appeal; and that an appeal should be taken within 15 days

from the notice of judgment or final order appealed from. While the

period to file an appeal is counted from the denial of the motion for

reconsideration, the appellant does not have the full fifteen (15) days.

The appellant only has the remaining time of the 15-day appeal period

to file the notice of appeal. Thus, some rules on appeals are:

Sec. 39. [B.P. 129] Appeals. The period for appeal from final orders,

resolutions, awards, judgments, or decisions of any court in all these

cases shall be fifteen (15) days counted from the notice of the final

order, resolution, award, judgment, or decision appealed from.

Provided, however, that in habeas corpus cases, the period for appeal

shall be (48) forty-eight hours from the notice of judgment appealed

from. x x x

SEC. 3. [Rule 41] Period of ordinary appeal. - The appeal shall be

taken within fifteen (15) days from the notice of the judgment or final

order appealed from. Where a record on appeal is required, the

appellant shall file a notice of appeal and a record on appeal within

thirty (30) days from the notice of judgment or final order.

The period to appeal shall be interrupted by a timely motion for new

trial or reconsideration. No motion for extension of time to file a

motion for new trial or reconsideration shall be allowed.

SEC. 6. [Rule 122] When appeal to be taken. An appeal must be

taken within fifteen (15) days from promulgation of the judgment or

from notice of the final order appealed from. This period for perfecting

an appeal shall be suspended from the time a motion for new trial or

reconsideration is filed until notice of the order overruling the motion

has been served upon the accused or his counsel at which time the

balance of the period begins to run.

IN WHAT CASES APPLICABLE

`Henceforth, this "fresh period rule" shall also apply to Rule 40

governing appeals from the Municipal Trial Courts to the Regional Trial

Courts; Rule 42 on petitions for review from the Regional Trial Courts

to the Court of Appeals; Rule 43 on appeals from quasi-judicial

agencies31 to the Court of Appeals and Rule 45 governing appeals by

certiorari to the Supreme Court.32 The new rule aims to regiment or

make the appeal period uniform, to be counted from receipt of the

order denying the motion for new trial, motion for reconsideration

(whether full or partial) or any final order or resolution. (Neypes,

supra)

Obviously, the new 15-day period may be availed of only if either

motion is filed; otherwise, the decision becomes final and executory

after the lapse of the original appeal period provided in Rule 41,

Section 3. (Neypes, supra)

The fresh period of 15 days becomes significant only when a party

opts to file a motion for new trial or motion for reconsideration. In this

manner, the trial court which rendered the assailed decision is given

another opportunity to review the case and, in the process, minimize

and/or rectify any error of judgment. While we aim to resolve cases

with dispatch and to have judgments of courts become final at some

definite time, we likewise aspire to deliver justice fairly. (Neypes,

supra)

APPLICATION IN CRIMINAL CASES

While Neypes involved the period to appeal in civil cases, the Courts

pronouncement of a "fresh period" to appeal should equally apply to

the period for appeal in criminal cases under Section 6 of Rule 122 of

the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, for the following reasons:

First, BP 129, as amended, the substantive law on which the Rules of

Court is based, makes no distinction between the periods to appeal in

a civil case and in a criminal case. Section 39 of BP 129 categorically

states that "[t]he period for appeal from final orders, resolutions,

awards, judgments, or decisions of any court in all cases shall be

fifteen (15) days counted from the notice of the final order, resolution,

award, judgment, or decision appealed from." Ubi lex non distinguit

nec nos distinguere debemos. When the law makes no distinction, we

(this Court) also ought not to recognize any distinction.

17

Second, the provisions of Section 3 of Rule 41 of the 1997 Rules of

Civil Procedure and Section 6 of Rule 122 of the Revised Rules of

Criminal Procedure, though differently worded, mean exactly the

same. There is no substantial difference between the two provisions

insofar as legal results are concerned the appeal period stops

running upon the filing of a motion for new trial or reconsideration and

starts to run again upon receipt of the order denying said motion for

new trial or reconsideration. It was this situation that Neypes

addressed in civil cases. No reason exists why this situation in criminal

cases cannot be similarly addressed.

Third, while the Court did not consider in Neypes the ordinary appeal

period in criminal cases under Section 6, Rule 122 of the Revised Rules

of Criminal Procedure since it involved a purely civil case, it did include

Rule 42 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure on petitions for review

from the RTCs to the Court of Appeals (CA), and Rule 45 of the 1997

Rules of Civil Procedure governing appeals by certiorari to this Court,

both of which also apply to appeals in criminal cases, as provided by

Section 3 of Rule 122 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, thus:

SEC. 3. How appeal taken. x x x x

(b) The appeal to the Court of Appeals in cases decided by the

Regional Trial Court in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction shall be

by petition for review under Rule 42.

x x x x

Except as provided in the last paragraph of section 13, Rule 124, all

other appeals to the Supreme Court shall be by petition for review on

certiorari under Rule 45.

Clearly, if the modes of appeal to the CA (in cases where the RTC

exercised its appellate jurisdiction) and to this Court in civil and

criminal cases are the same, no cogent reason exists why the periods

to appeal from the RTC (in the exercise of its original jurisdiction) to

the CA in civil and criminal cases under Section 3 of Rule 41 of the

1997 Rules of Civil Procedure and Section 6 of Rule 122 of the Revised

Rules of Criminal Procedure should be treated differently.

Were we to strictly interpret the "fresh period rule" in Neypes and

make it applicable only to the period to appeal in civil cases, we shall

effectively foster and encourage an absurd situation where a litigant in

a civil case will have a better right to appeal than an accused in a

criminal case a situation that gives undue favor to civil litigants and

unjustly discriminates against the accused-appellants. It suggests a

double standard of treatment when we favor a situation where

property interests are at stake, as against a situation where liberty

stands to be prejudiced. We must emphatically reject this double and

unequal standard for being contrary to reason. Over time, courts have

recognized with almost pedantic adherence that what is contrary to

reason is not allowed in law Quod est inconveniens, aut contra

rationem non permissum est in lege.

18

(Judith Yu versus Hon. Rosa

Samson-Tatad, G.R. No. 170979, 09 Feb. 2011)

RETROACTIVE EFFECT

The determinative issue is whether the "fresh period" rule announced

in Neypes could retroactively apply in cases where the period for

appeal had lapsed prior to 14 September 2005 when Neypes was

promulgated. That question may be answered with the guidance of the

general rule that procedural laws may be given retroactive effect to

actions pending and undetermined at the time of their passage, there

being no vested rights in the rules of procedure.

17

Amendments to

procedural rules are procedural or remedial in character as they do not

create new or remove vested rights, but only operate in furtherance of

the remedy or confirmation of rights already existing.

18

Sps. De los Santos reaffirms these principles and categorically

warrants that Neypes bears the quested retroactive effect, to wit:

Procedural law refers to the adjective law which prescribes rules and

forms of procedure in order that courts may be able to administer

justice. Procedural laws do not come within the legal conception of a

retroactive law, or the general rule against the retroactive operation of

statues ! they may be given retroactive effect on actions pending and

undetermined at the time of their passage and this will not violate any

right of a person who may feel that he is adversely affected, insomuch

as there are no vested rights in rules of procedure.

The "fresh period rule" is a procedural law as it prescribes a fresh

period of 15 days within which an appeal may be made in the event

that the motion for reconsideration is denied by the lower court.

Following the rule on retroactivity of procedural laws, the "fresh period

rule" should be applied to pending actions, such as the present case.

Also, to deny herein petitioners the benefit of the "fresh period rule"

will amount to injustice, if not absurdity, since the subject notice of

judgment and final order were issued two years later or in the year

2000, as compared to the notice of judgment and final order

in Neypes which were issued in 1998. It will be incongruous and

illogical that parties receiving notices of judgment and final orders

issued in the year 1998 will enjoy the benefit of the "fresh period

rule" while those later rulings of the lower courts such as in the instant

case, will not.

19

Notably, the subject incidents in Sps. De los Santos occurred in August

2000, at the same month as the relevant incidents at bar. There is no

reason to adopt herein a rule that is divergent from that in Sps. De los

Santos. (Fil-Estate Properties, Inc. versus Hon. Marietta Homena J.

Valencia, G.R. No. 173942, 25 June 2008)

NOT INCONSISTENT WITH RULES OF COURT

This pronouncement is not inconsistent with Rule 41, Section 3 of the

Rules which states that the appeal shall be taken within 15 days from

notice of judgment or final order appealed from. The use of the

disjunctive word "or" signifies disassociation and independence of one

thing from another. It should, as a rule, be construed in the sense in

which it ordinarily implies.33 Hence, the use of "or" in the above

provision supposes that the notice of appeal may be filed within 15

days from the notice of judgment or within 15 days from notice of the

"final order," which we already determined to refer to the July 1, 1998

order denying the motion for a new trial or reconsideration. (Neypes,

supra)

You might also like

- Legal Forms ThesisDocument21 pagesLegal Forms ThesisTsuuundereeNo ratings yet

- Guy vs. Guy (2012)Document23 pagesGuy vs. Guy (2012)Angelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Appellant's Brief Cyber LibelDocument15 pagesAppellant's Brief Cyber LibelRonie A100% (1)

- Casino V PajeDocument2 pagesCasino V PajeKharla M Valdevieso AbelleraNo ratings yet

- Ownership and Participation As Heirs"Document7 pagesOwnership and Participation As Heirs"Christine Rose Bonilla LikiganNo ratings yet

- PEU Dispute Over Increased Agency FeesDocument7 pagesPEU Dispute Over Increased Agency Feesalwayskeepthefaith8No ratings yet

- Nestle Vs PuedanDocument9 pagesNestle Vs Puedanbeljoe12345No ratings yet

- Vestas Services Philippines v. CIR on Zero-Rated VAT RefundDocument1 pageVestas Services Philippines v. CIR on Zero-Rated VAT RefundAnna Dominique Gevaña MarmolNo ratings yet

- Braga vs. AbayaDocument6 pagesBraga vs. AbayaReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- The Civil Code of The PhilippinesDocument268 pagesThe Civil Code of The PhilippinesJose Kenn Pueyo BilbaoNo ratings yet

- Joint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsDocument2 pagesJoint Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsNikki SiaNo ratings yet

- Estipona CaseDocument19 pagesEstipona CaseKar EnNo ratings yet

- Recent Jurisprudence: Civil LawDocument70 pagesRecent Jurisprudence: Civil LawRoi DizonNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality of K12Document1 pageConstitutionality of K12AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Forest TreesDocument164 pagesForest TreesLesterNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 (Banking)Document108 pagesLecture 2 (Banking)miles1280100% (1)

- General Milling Vs CADocument5 pagesGeneral Milling Vs CAJohnday MartirezNo ratings yet

- Discuss Exhaustively The Case of Navarro VsDocument3 pagesDiscuss Exhaustively The Case of Navarro VsAnthony Angel TejaresNo ratings yet

- CHR Statement On Drug-Related Killings Under DuterteDocument2 pagesCHR Statement On Drug-Related Killings Under DuterteRapplerNo ratings yet

- JUDGE ABUSED POWER DISMISSING CASESDocument2 pagesJUDGE ABUSED POWER DISMISSING CASESAngela Louise SabaoanNo ratings yet

- Political law review answers moduleDocument6 pagesPolitical law review answers moduleAllaric Luig Babas PalmaresNo ratings yet

- CHED Scholarship Study Leave RequestDocument1 pageCHED Scholarship Study Leave RequestFloni Mae Nieves BaisNo ratings yet

- Regalado Vs GoDocument13 pagesRegalado Vs GopyulovincentNo ratings yet

- LGUs challenge SC ruling allowing tax deferralDocument7 pagesLGUs challenge SC ruling allowing tax deferralJon JamoraNo ratings yet

- Noel Masanque Narrative Report FormatDocument14 pagesNoel Masanque Narrative Report FormatCrisamor Rose Pareja ClarisaNo ratings yet

- MOLINA DOCTRINEDocument1 pageMOLINA DOCTRINEMaria LucesNo ratings yet

- Remediallaw AlbanoDocument15 pagesRemediallaw AlbanoJosephine Dominguez RojasNo ratings yet

- Tax 2Document99 pagesTax 2Francis PunoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines National Capital Judicial Region Metropolitan Trial Court of Mandaluyong City Mandaluyong City, Branch 07Document1 pageRepublic of The Philippines National Capital Judicial Region Metropolitan Trial Court of Mandaluyong City Mandaluyong City, Branch 07Karen RonquilloNo ratings yet

- Eternal Garden Memeorial Park Corporation vs. Court of AppealsDocument14 pagesEternal Garden Memeorial Park Corporation vs. Court of AppealsRomy Ian LimNo ratings yet

- Anti-Age Discrimination in Employment ActDocument1 pageAnti-Age Discrimination in Employment ActKarissa TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules on Civil Liability for Killing Despite Criminal AcquittalDocument67 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Civil Liability for Killing Despite Criminal AcquittalThea Thei YaNo ratings yet

- Remedial Law Suggested Answers 1997 2006 WordDocument79 pagesRemedial Law Suggested Answers 1997 2006 WordpdalingayNo ratings yet

- Arellano University Remedial Law SyllabusDocument15 pagesArellano University Remedial Law SyllabusMariya Klara MalaviNo ratings yet

- 2011 Bar Examination Questionnaire For Remedial LawDocument28 pages2011 Bar Examination Questionnaire For Remedial LawYsabel ReyesNo ratings yet

- LTD Cases Last PartDocument4 pagesLTD Cases Last PartlexxNo ratings yet

- R.A. 9231 and DO 65-04Document22 pagesR.A. 9231 and DO 65-04Kriza Forte QuiranteNo ratings yet

- Philippine Pizza, Inc. v. Cayetano PDFDocument8 pagesPhilippine Pizza, Inc. v. Cayetano PDFAnnieNo ratings yet

- Perlas-Bernabe Cases SyllabusDocument682 pagesPerlas-Bernabe Cases SyllabusAll Blue100% (9)

- Paringit's Disability Claims UpheldDocument4 pagesParingit's Disability Claims UpheldBong OrduñaNo ratings yet

- The Concept of The State PDFDocument53 pagesThe Concept of The State PDFchristie joiNo ratings yet

- Land Titles - Atty. Padilla - Ateneo Law SchoolDocument2 pagesLand Titles - Atty. Padilla - Ateneo Law SchoolFrances Lipnica PabilaneNo ratings yet

- Part I. 2-Point QuestionsDocument5 pagesPart I. 2-Point QuestionsLily MondaragonNo ratings yet

- Chavez Vs NhaDocument42 pagesChavez Vs NhaChristopher Joselle MolatoNo ratings yet

- 1992 Declaration of RioDocument4 pages1992 Declaration of RioSoveja LucianNo ratings yet

- Cir V Pascor Realty & Dev'T Corp Et. Al. GR No. 128315, June 29, 1999Document8 pagesCir V Pascor Realty & Dev'T Corp Et. Al. GR No. 128315, June 29, 1999Cristy Yaun-CabagnotNo ratings yet

- Election Law CasesDocument315 pagesElection Law CasesPearl Angeli Quisido CanadaNo ratings yet

- Basilonia V Villaruz PDFDocument10 pagesBasilonia V Villaruz PDFbrida athenaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Alfredo Cullado v Dominic GutierrezDocument11 pagesHeirs of Alfredo Cullado v Dominic GutierrezBrandon BanasanNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Torts and Damages For January 8Document2 pagesAssignment in Torts and Damages For January 8Grester FernandezNo ratings yet

- IV. UP - Procedure and Professional EthicsDocument132 pagesIV. UP - Procedure and Professional EthicsNiño Galeon MurilloNo ratings yet

- 2nd LIST OF CASES: Philippine Case Law SummariesDocument4 pages2nd LIST OF CASES: Philippine Case Law SummariesGF Sotto100% (1)

- Comelec Resolution 9631Document5 pagesComelec Resolution 9631BlogWatchNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Investigation Rules and ProceduresDocument3 pagesPreliminary Investigation Rules and ProceduresDomi EsnarNo ratings yet

- Boticano V Chu DigestDocument1 pageBoticano V Chu DigestJermone MuaripNo ratings yet

- Saligumba V PalanogDocument9 pagesSaligumba V PalanogIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Discussion On Labor LawDocument5 pagesDiscussion On Labor Lawmichelle m. templadoNo ratings yet

- Taxpayer Defends Against Tax Evasion CaseDocument23 pagesTaxpayer Defends Against Tax Evasion CaseTauniño Jillandro Gamallo NeriNo ratings yet

- Appeal - Fresh Period Rule or The Neypes Rule 12-12-14Document9 pagesAppeal - Fresh Period Rule or The Neypes Rule 12-12-14Macky GallegoNo ratings yet

- Fresh 15-Day Appeal Period DoctrineDocument3 pagesFresh 15-Day Appeal Period DoctrineSK Tim RichardNo ratings yet

- Employer-Employee Relationship CasesDocument190 pagesEmployer-Employee Relationship CasesEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Corporation Code OutlineDocument8 pagesCorporation Code OutlineEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument209 pagesCase DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- 4th Set LabRelDocument13 pages4th Set LabRelEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Transportation LawDocument150 pagesTransportation Lawjum712100% (3)

- PilDocument32 pagesPilEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Employer-Employee Relationship CasesDocument190 pagesEmployer-Employee Relationship CasesEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Torts Memory Aid AteneoDocument11 pagesTorts Memory Aid AteneoStGabrielleNo ratings yet

- LABOR ChanRoblesDocument52 pagesLABOR ChanRoblesEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Summary of PleadingsDocument1 pageSummary of PleadingsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Loon vs. Power MasterDocument2 pagesLoon vs. Power MasterEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Transpo 16 - 20Document119 pagesTranspo 16 - 20Eloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- NLRC Rules of Procedure 2011Document30 pagesNLRC Rules of Procedure 2011Angela FeliciaNo ratings yet

- NLRC Ruling on Illegal Dismissal UpheldDocument22 pagesNLRC Ruling on Illegal Dismissal UpheldEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of DesistanceDocument1 pageAffidavit of DesistanceEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Law OutlineDocument7 pagesNegotiable Instruments Law OutlineEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan Case DigestDocument3 pagesAmpatuan Case DigestEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Philippines Corporation CodeDocument68 pagesPhilippines Corporation CodeEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Commendador vs. de VillaDocument1 pageCommendador vs. de VillaEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Amp AtuanDocument8 pagesAmp AtuanEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Notes in Corporation LawDocument47 pagesNotes in Corporation LawEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- 1st Batch of Consti DigestsDocument56 pages1st Batch of Consti DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Amp AtuanDocument8 pagesAmp AtuanEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Education Science Tachnology Arts Culture SportsDocument103 pagesEducation Science Tachnology Arts Culture SportsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Property Case Digests 1Document8 pagesProperty Case Digests 1Eloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- NEGO Case DigestsDocument4 pagesNEGO Case DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- NEGO Case DigestsDocument4 pagesNEGO Case DigestsEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Consti Law IDocument925 pagesConsti Law IEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- The Philippines As A StateDocument263 pagesThe Philippines As A StateEloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- Madurai HC Palani Temple JudgmentDocument22 pagesMadurai HC Palani Temple JudgmentPGurus100% (2)

- CSC LAW & RulesDocument185 pagesCSC LAW & RulesConnie SulangNo ratings yet

- Self-defense plea rejected in homicide caseDocument4 pagesSelf-defense plea rejected in homicide caseaudreyracelaNo ratings yet

- 20 - Proposal For Legal ServiceDocument5 pages20 - Proposal For Legal ServiceMendra Siagian0% (1)

- Central Bay Reclamation and Dev. Corp. vs. COA and PRADocument14 pagesCentral Bay Reclamation and Dev. Corp. vs. COA and PRAsamantha.makayan.abNo ratings yet

- LEGRES Doctrine of Equality of StatesDocument14 pagesLEGRES Doctrine of Equality of StatesRhic Ryanlhee Vergara FabsNo ratings yet

- Wandering Dago DefendantsDocument26 pagesWandering Dago DefendantsCasey SeilerNo ratings yet

- Bank Accounts and Plunder CasesDocument5 pagesBank Accounts and Plunder CasesFaithmaeNo ratings yet

- Agency Contract AgreementDocument4 pagesAgency Contract Agreementkatpotayre potayreNo ratings yet

- Letter To Judge Hummel (8-19-22) Serious Crime Against Witness Kevin Murphy. Subpoena DCJS Records Necessary.Document3 pagesLetter To Judge Hummel (8-19-22) Serious Crime Against Witness Kevin Murphy. Subpoena DCJS Records Necessary.Desiree YaganNo ratings yet

- Jamora V MeerDocument1 pageJamora V MeerpyriadNo ratings yet

- Equitable PCI v. Arcelito Tan, G.R. No. 165339Document2 pagesEquitable PCI v. Arcelito Tan, G.R. No. 165339xxxaaxxxNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Liberal Commission 1992 Policy & 1993 PlatformDocument47 pagesAboriginal Liberal Commission 1992 Policy & 1993 PlatformRussell Diabo100% (1)

- Retaining Graduate MembershipDocument3 pagesRetaining Graduate MembershipahmedanyNo ratings yet

- Criminal Liability of Receiver of Stolen GoodsDocument19 pagesCriminal Liability of Receiver of Stolen GoodsÃýuśh RâjNo ratings yet

- (Case) Reyes v. Ines-LucianoDocument6 pages(Case) Reyes v. Ines-LucianoRubyNo ratings yet

- Form 1 Standard Form of Rental Agreement: PartiesDocument5 pagesForm 1 Standard Form of Rental Agreement: PartiesJane NguyenNo ratings yet

- Equal Pay ComplaintDocument18 pagesEqual Pay ComplaintWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNo ratings yet

- CivPro Atty. Custodio Case DigestsDocument12 pagesCivPro Atty. Custodio Case DigestsRachel CayangaoNo ratings yet

- Remolona V CSCDocument2 pagesRemolona V CSCJM PabustanNo ratings yet

- LLB Notes Family Law 1 Hindu LawDocument27 pagesLLB Notes Family Law 1 Hindu LawAadhar Saha100% (1)

- Rosales vs. Rosales, G.R. No. L-40789, 148 SCRA 59, February 27, 1987Document3 pagesRosales vs. Rosales, G.R. No. L-40789, 148 SCRA 59, February 27, 1987AliyahDazaSandersNo ratings yet

- Titles of NobilityDocument157 pagesTitles of NobilityLisa_SageNo ratings yet

- Cruz v. Youngberg, G.R. No. L-34674, October 26, 1931: 11. (Supplementary and Contingent Regulation)Document3 pagesCruz v. Youngberg, G.R. No. L-34674, October 26, 1931: 11. (Supplementary and Contingent Regulation)SALMAN JOHAYRNo ratings yet

- People V Echagaray, G.R. No. 117472Document9 pagesPeople V Echagaray, G.R. No. 117472JM CamposNo ratings yet

- Aro Vs NanawaDocument8 pagesAro Vs NanawaulticonNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument11 pagesCase AnalysisAshutosh DohareyNo ratings yet

- Policies of SbiDocument10 pagesPolicies of Sbiyadavmihir63No ratings yet

- Roman Catholic Archbishop of Caceres Vs Secretary of Agrarian Reform Et AlDocument6 pagesRoman Catholic Archbishop of Caceres Vs Secretary of Agrarian Reform Et AlKing BadongNo ratings yet

- 3 Wk. Presentation, Ppt. General and Christian Ethical Principles, 2021Document26 pages3 Wk. Presentation, Ppt. General and Christian Ethical Principles, 2021JohnPaul UchennaNo ratings yet

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessFrom EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceFrom EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceNo ratings yet

- 2018 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2018 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet

- Patent Trolls: Predatory Litigation and the Smothering of InnovationFrom EverandPatent Trolls: Predatory Litigation and the Smothering of InnovationNo ratings yet

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadFrom EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Courage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomFrom EverandCourage to Stand: Mastering Trial Strategies and Techniques in the CourtroomNo ratings yet

- 2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActFrom Everand2017 Commercial & Industrial Common Interest Development ActNo ratings yet

- Evil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainFrom EverandEvil Angels: The Case of Lindy ChamberlainRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Winning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsFrom EverandWinning with Financial Damages Experts: A Guide for LitigatorsNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff 101: The Black Book of Inside Information Your Lawyer Will Want You to KnowFrom EverandPlaintiff 101: The Black Book of Inside Information Your Lawyer Will Want You to KnowNo ratings yet

- The Chamberlain Case: the legal saga that transfixed the nationFrom EverandThe Chamberlain Case: the legal saga that transfixed the nationNo ratings yet

- After Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do about ItFrom EverandAfter Misogyny: How the Law Fails Women and What to Do about ItNo ratings yet

- Diary of a DA: The True Story of the Prosecutor Who Took on the Mob, Fought Corruption, and WonFrom EverandDiary of a DA: The True Story of the Prosecutor Who Took on the Mob, Fought Corruption, and WonRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Strategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientFrom EverandStrategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Myth of the Litigious Society: Why We Don't SueFrom EverandThe Myth of the Litigious Society: Why We Don't SueRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Scorched Worth: A True Story of Destruction, Deceit, and Government CorruptionFrom EverandScorched Worth: A True Story of Destruction, Deceit, and Government CorruptionNo ratings yet

- Religious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of UncertaintyFrom EverandReligious Liberty in Crisis: Exercising Your Faith in an Age of UncertaintyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)