Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ariz Law

Uploaded by

eze24Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ariz Law

Uploaded by

eze24Copyright:

Available Formats

Elite Page 1

CHAPTER 1

OVERVIEW OF

ARIZONA PHARMACY LAW

(2 CONTACT HOURS - Required)

By Katie Ingersoll, RPh, Pharm D and staff pharmacist

for national chain.

Author Disclosure: Katie Ingersoll and Elite

Professional Education do not have any actual or

potential conficts of interest in relation to this lesson.

Universal Activity Number (UAN):

0761-9999-13-275-H03-T

Activity Type: Knowledge-based

Initial Release Date: July 30, 2013

Expiration Date: July 30, 2015

Target Audience: Pharmacy Technicians in a

community-based setting.

To Obtain Credit: A minimum test score of 70 percent

is needed to obtain a credit. Please submit your answers

either by mail, fax, or online at www.elitecme.com.

Questions regarding statements of credit and other

customer service issues should be directed to 1-888-

666-9053. This lesson is $10.00.

Educational Review Systems is accredited

by the Accreditation Council of Pharmacy

Education (ACPE) as a provider of

continuing pharmaceutical education. This

program is approved for 2 hours (0.2

CEUs) of continuing pharmacy education credit. Proof

of participation will be posted to your NABP CPE

profle within 4 to 6 weeks to participants who have

successfully completed the post-test. Participants must

participate in the entire presentation and complete the

course evaluation to receive continuing pharmacy

education credit.

Learning objectives

! Describe the members of the Arizona Board

of Pharmacy, including how many there are,

their qualifcations, and how they become

eligible for board appointment.

! List the responsibilities of the Arizona Board

of Pharmacy.

! Describe pharmacy setup and security

requirements.

! List the types of prescribers who may

prescribe medications in the state of Arizona

and any restrictions on their prescribing

authority.

! Discuss requirements for flling prescriptions

in Arizona, including requirements for

flling prescriptions written by Mexican and

Canadian prescribers.

! Explain generic substitution requirements

in Arizona and when it is appropriate to

dispense a generic medication.

! Describe the valid time frame for dispensing

reflls of medications in Arizona, including

reflls and time frame restrictions on

controlled substances.

! Discuss the regulations on the dispensing of

controlled substances without a prescription,

including quantity limits and record keeping.

! Describe the requirements for the sale of

pseudoephedrine, including quantity limits

and record keeping.

! Explain patient counseling requirements and

who can counsel a patient.

pharmacist actively working at a licensed

hospital. Pharmacists can serve fve-year terms

on the Board of Pharmacy.

The pharmacy technician member of the Board

of Pharmacy must have at least fve years of

experience actively working in a pharmacy, and

must have been a resident of Arizona for the fve-

year period preceding appointment. Pharmacy

technicians may serve a fve-year term on the

board. The two public members also are required

to have residency status in Arizona for the fve

years preceding their appointment, and may serve

a fve-year term unless they are removed by the

governor. All members of the Arizona Board of

Pharmacy are appointed by the governor.

The Board of Pharmacy must elect a president

and vice-president annually. The president must

be present at all board meetings; the vice-

president may act in place of the president if the

president is not present. The Board of Pharmacy

must hold at least four meetings per year and

provide an annual report to the governor,

including the names of all persons and facilities

licensed by the Board of Pharmacy.

The Board of Pharmacy is responsible for

developing and maintaining laws and rules

to protect the public on any issue related to

pharmacies, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians,

the storage, distribution or manufacture of

medications, and the practice of pharmacy. It is

also responsible for the enforcement of its rules

and laws.

To properly enforce pharmacy rules and laws,

the Board of Pharmacy or its designated

employees have the right to enter any pharmacy,

manufacturing plant, wholesaler, storage facility,

or vehicle used in the manufacture, storage, or

sale of prescription medications. Inspections can

be conducted at any time the facility in question

is open, and prior notice is not required.

The Board of Pharmacy is also responsible for

providing notice at least once every three months

of any changes to prescribing authority of any

prescriber licensed to practice in Arizona.

Pharmacy setup and security

Pharmacies in Arizona must have a dispensing,

compounding, and drug stocking area that is at

least 300 feet.

2

If the minimum pharmacy size

is used, no more than three personnel may work

at the same time. Each additional staff member

requires an additional 60 feet

2

of foor space. This

is to allow pharmacists adequate space to monitor

the activities of pharmacy personnel and ensure

effcient workfow.

Each employee working at the same time should

have at least 3 feet

2

of counter space, and it must

be at least 16 inches deep and 24 inches long to

be sure all of them have space to spread out their

work to minimize error potential.

Counter space should be contained by a barrier

at least 66 inches tall to prevent unauthorized

persons from seeing the pharmacy counter,

potentially violating a patients privacy. The foor

! Describe prescription transfer regulations and

what information must be recorded during a

prescription transfer.

! Explain the pharmacy record keeping

requirements under Arizona law.

! Describe the licensing requirements for

pharmacies and the types of permits that may

be issued by the Arizona Board of Pharmacy,

as well as renewal requirements.

! Discuss the licensing and continuing

education requirements for pharmacists.

! Discuss the responsibilities of pharmacy

interns and their licensing requirements.

! Discuss the responsibilities of pharmacy

technicians and their licensing and continuing

education requirements.

! Describe regulations on immunization by

pharmacists, including the certifcation

process and who can be immunized.

! List the vaccines that require a prescription to

be administered to an adult patient.

Introduction

State laws and regulations governing pharmacy

practice are extremely important in the day-to-

day work of a pharmacy associate. From the

license needed to work in the pharmacy to the

foor space necessary for each employee, laws

and regulations govern every aspect of daily

pharmacy operation. As a pharmacy employee, it

is imperative to maintain a working knowledge of

state pharmacy laws, and continue to learn about

new laws that have been passed as well.

All states have variations in their state pharmacy

laws that distinguish them from other states.

While state laws in Arizona are similar to others,

there are signifcant differences that must also

be reviewed. This course is designed to be an

overview of the pertinent state pharmacy laws

in Arizona for the pharmacist and pharmacy

technician.

Information included in this course was current as

of the time of writing. Remember that laws may

change, and be sure to consult the Arizona State

Law Book for a thorough explanation of each

law. This course is an overview of the pertinent

Arizona state laws, and may not be all-inclusive

see the law book for full details.

Arizona State Board of Pharmacy

The Arizona State Board of Pharmacy is the

governing body for pharmacy affairs in the state

of Arizona, and is also responsible for issuing

licenses to pharmacists, interns, technicians,

pharmacies, drug wholesalers, and drug

manufacturers.

The board consists of nine members: six

pharmacists, one pharmacy technician, and two

members of the public. The pharmacists who are

members of the Board of Pharmacy must have

at least 10 years of experience before they are

eligible for appointment, and at least fve years of

experience as a licensed pharmacist in Arizona.

Pharmacist members must have been a resident of

Arizona for the fve years preceding appointment.

There must be at least one actively practicing

community pharmacist, and at least one

Page 2 Elite

space along the dispensing and compounding

counter must be at least 36 inches wide.

New pharmacies must have a separate patient

counseling area to allow patients privacy during

consultation.

NOTE: Pharmacy size regulations must be

addressed and discussed with the Board of

Pharmacy when applying for a permit to operate

a pharmacy.

Controlled substances can be kept in a safe or

locked cabinet or distributed throughout the

stock of prescription medications; it is up to the

pharmacy to decide what best suits its needs to

maximize effciency and minimize theft.

The pharmacy must be surrounded from foor

to ceiling by a permanent barrier with secure

entry points. It should be designed in a way that

the pharmacist is the only person who can gain

entry to the area where prescription medications

and controlled substances are kept, and only

a licensed pharmacist may carry a key to the

pharmacy.

All prescription medications and medical devices

must be stored in a clean, organized space that

is well lit, well ventilated, dry, and maintains

adequate temperatures for medication storage.

A separate drug storage area outside of the

pharmacy may be used if necessary, but it must

be enclosed from foor to ceiling by a secure

barrier that only the pharmacist can access with

a key.

Who can prescribe medications in

Arizona?

1,3

In the state of Arizona, many different types

of practitioners can prescribe medications to

patients. Some of these prescribers have limits

to their prescription authority, such as treatment

limited to certain body parts or limits to the

prescription of controlled substances. It is very

important to be aware of the various types of

prescribers and their authority limits to ensure

prescriptions are flled within the limits of the

law.

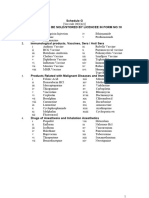

Type of prescriber Prescription authority

Medical doctor Independent prescribing

authority, unlimited.

Doctor of

osteopathy

Independent prescribing

authority, unlimited.

Dentist Independent prescribing

authority limited to

scope of practice

prescribing authority is

limited to treatment of

mouth, teeth and gums.

Podiatrist Independent prescribing

authority limited to

scope of practice

prescribing authority

is limited to treatment

of feet; can prescribe

controlled substances

with board approval.

Veterinarian Independent prescribing

authority limited to

scope of practice

prescribing authority is

limited to treatment of

animals.

Physician assistant Can prescribe non-

controlled medications

without limits.

Controlled substances

can only be prescribed

with written consent of

a supervising physician,

and only up to a 30-

day supply may be

prescribed at once.

2

Registered nurse

practitioner

Can prescribe non-

controlled and controlled

medications with board

approval, independent

prescribing authority.

EMT/paramedic Does not have any

prescribing authority.

Chiropractor Does not have any

prescribing authority.

Naturopathic

doctor

Limited independent

prescribing authority

cannot prescribe

chemotherapy,

antipsychotics, or

IV medications. Can

prescribe controlled

substances, except

the only Schedule II

medication that may be

prescribed is morphine.

Schedule III-V

controlled substances

can be prescribed.

Optometrist Limited independent

prescribing authority.

Can prescribe non-

controlled medications

with board approval;

the only controlled

medications that may

be prescribed are

Schedule III analgesics.

Prescribing quantity

limitations may apply.

Pharmacist Can start, alter, or

discontinue medication

therapy under a

collaborative agreement

with a supervising

physician. May also

administer most

immunizations without a

prescription after earning

certifcation.

Prescription requirements in Arizona

Prescriptions flled in Arizona must meet the

following requirements:

Prescriptions must be written by a prescriber

with prescribing authority in Arizona as noted

in the chart in the previous section.

Handwritten prescriptions must include the

prescribers actual signature.

Prescription orders sent to the pharmacy

in electronic format must include the

prescribers electronic signature, and must

be printed or reduced to writing before flling

the prescription.

Written prescriptions that are printed from an

electronic database and given to the patient

may use the prescribers actual or electronic

signature. Printed prescriptions given to

a patient that only use the prescribers

electronic signature must be printed on

tamper-resistant paper.

Oral prescription orders may be called in to

the pharmacy if the pharmacist reduces the

prescription to writing immediately.

Reflls may be given if authorized by the

prescriber and if they are documented and

fled properly by the pharmacist.

Prescription orders may also be sent by the

prescribers offce via fax or electronic mail.

The patient may send prescription orders via

fax or email if the prescription hard copy is

presented to the pharmacy upon pickup of the

medication.

All written prescriptions flled for patients

using Arizona Medicaid or federal Medicare

services for payment must be printed on

tamper-resistant paper to prevent copying and

fraud. This requirement is not to be applied

to prescriptions sent to the pharmacy by fax,

email, or verbally.

4

All prescriptions flled in Arizona must have a

paper version that must be fled and kept for at

least seven years. Prescriptions must be issued

a serial number, and the date the prescription

was flled must be placed on the prescription

before fling. Prescriptions should be fled in the

order in which they were dispensed. This fle

may be maintained electronically by scanning

the prescription images, as long as they are

readily retrievable upon request by the Board of

Pharmacy or its agents. These regulations also

apply to hospital pharmacy prescription records.

Prescriptions for non-controlled substances

written by prescribers licensed by appropriate

licensing boards in Canada or Mexico may

be flled in Arizona. Prescriptions written for

Elite Page 3

federally controlled substances by Canadian or

Mexican prescribers may not be flled in Arizona.

Canadian and Mexican prescriptions must be kept

in a separate fle for retrieval, and must be kept

for seven years as well.

Generic substitution and DAW

Prescriptions flled in Arizona should be

dispensed as they are written if the prescriber

writes on the prescription any variation of the

terms DAW, dispense as written, or do not

substitute. The generic product substituted for

the brand name written on the prescription must

FDA-approved and listed as bioequivalent to

the brand name product in the Orange Book. If

a generic product is given, the price for both the

brand name and generic product must be given to

the patient if the prescription is not billed to an

insurance plan.

The generic product may not be given if the

manufacturer does not print an expiration date on

the products packaging, or if the manufacturer

does not have a program for the recall of unsafe

or fawed products. The patient may choose to

have the brand name dispensed if the prescriber

did not specify that the brand name is medically

necessary.

Reflls and valid time frame for flling

prescriptions

All prescriptions flled in Arizona have a valid

time frame in which the original prescription and

available reflls may be flled, depending on the

type of medication ordered. Prescriptions flled in

Arizona for non-controlled substances are valid

for one year from the written date, and may only

be reflled within this time frame.

Prescriptions for schedule III-V controlled

substances are valid for six months from the

written date, and may be reflled up to fve times.

Schedule II prescriptions are valid for 90 days

from the written date and may not be reflled.

Dispensing controlled substances without

prescription

In the state of Arizona, certain controlled

substances can be dispensed without a

prescription under specifc conditions. Patients

who are at least 18 years old can purchase certain

controlled substances from a pharmacist if all of

the following criteria are met:

It must be requested for legitimate medical

treatment.

No more than 240 mL or 48 dosage units of

any controlled substances containing opium,

or 120 mL or 24 dosage units of any other

controlled substances may be dispensed to

the same person within 48 hours.

No more than 120 dosage units of any

product that contains only ephedrine may be

dispensed within 30 days.

Any patient who is not known to the

pharmacist must provide identifcation and

proof of age.

A record book must be used to collect

information about the person purchasing

the controlled substance, including name

and address of the person purchasing the

product, the quantity and name of the product

purchased, the date the purchase was made,

and the name or initials of the pharmacist

overseeing the sale.

The bottle must be labeled with the

pharmacys name and address, date product

was dispensed, serial number, prescribers

name, patients name, directions for using

the product, and any warning statements

necessary. If a controlled substance, it must

also include the federally required warning:

Caution: federal law prohibits the transfer of

this drug to any person other than the patient

for whom it was prescribed.

Pseudoephedrine is regulated in Arizona

because it is a common product used in the

manufacture of methamphetamine. Regulations

have been put in place to deter people from

purchasing large amounts of pseudoephedrine

for methamphetamine production to decrease the

production of this drug in Arizona.

In most instances, Arizona state regulations on

pseudoephedrine sales are less restrictive than

federal laws, so federal laws must be followed in

Arizona. These regulations include:

5

All sales must be recorded in a logbook.

The logbook may be electronic or on

paper.

It must be readily retrievable and

maintained for at least two years.

It must record the name and address of

the person purchasing pseudoephedrine,

the date and time the sale was made,

the name and quantity of the product

purchased, and include the signature of

the purchaser.

A state-issued photo identifcation card,

drivers license, or passport must be

presented at time of purchase.

All products containing pseudoephedrine

must be kept behind the counter or in a

locked cabinet, and can only be sold under

the supervision of a licensed pharmacist.

There are strict limits to how much

pseudoephedrine can be purchased at once.

No more than 9 grams of pseudoephedrine

may be purchased by a single person within

a 30-day period, and no more than 3.6

grams may be purchased per person per

day. This is to decrease the availability of

pseudoephedrine and limit its use in the

production of methamphetamine.

Mail order or Internet retailers are limited

to shipping no more than 7.5 grams of

pseudoephedrine within a 30-day period.

These rules do not apply to prescriptions

written for pseudoephedrine only

for over-the-counter sales without a

prescription.

Patient counseling

Patient counseling must occur on all new

prescriptions dispensed to the patient. Counseling

must be conducted by a licensed pharmacist or

intern under the direct supervision of a licensed

pharmacist, and should include an overview of

the medication, including its brand and generic

names, directions for use, contraindications as

appropriate, and adverse effects. The patient or

his or her representative should be given time to

ask questions and receive appropriate answers.

Counseling is not required on reflls unless there

is a change in directions or dosage.

Transferring prescriptions

Prescriptions may be transferred between

pharmacies by pharmacists or graduate interns.

When a prescription is transferred out, it must

be invalidated by the transferring pharmacy

by writing VOID on the original prescription

hard copy, or ensuring it is invalidated in the

pharmacys dispensing computer system.

The name, address, and phone number or other

means of identifcation of the receiving pharmacy

shall be copied onto the back of the hard copy

prescription or saved in the pharmacys computer

system.

The prescription order for a non-controlled

substance taken down by the receiving pharmacy

must include the word transfer, the original

written date of the prescription, the frst and

last dates the prescription was dispensed, the

original number of reflls, the number of reflls

remaining, the name, address, and phone number

of the original pharmacy or other identifying

information, the prescription number at the

original pharmacy, the name of the pharmacist or

graduate intern the prescription was transferred

from, and the name of the receiving pharmacist

or graduate intern.

Prescriptions for Schedule III, IV, and V

controlled substances may only be transferred

between two licensed pharmacists, and may only

be transferred one time. The same information as

for a non-controlled substance is recorded for a

controlled substance, and both pharmacists must

record the DEA number of the other pharmacy on

the transfer order.

Prescriptions may be transferred into Arizona

from out of state if they meet all of the above

requirements for prescription transfers and are

prescribed by a prescriber with prescriptive

authority in Arizona. See section titled Who

can prescribe in Arizona? for details on what

prescribers have prescriptive authority in

Arizona.

Record keeping requirements

All records must be kept in a readily accessible

area for seven years. This includes prescription

hard copies, daily sales records, immunization

records, prescription transfer records, logbooks

for pseudoephedrine and controlled substance

sales, and any records required to be kept by

federal or state laws.

Pharmacy licensure

All pharmacies, drug wholesalers, drug storage

facilities, and drug manufacturers in Arizona

must be licensed with the Board of Pharmacy,

and these licenses must be renewed every

other year. Pharmacies not located in Arizona

that deliver medications to patients in Arizona

must also be registered with the state Board of

Pharmacy in Arizona.

Page 4 Elite

Application for a license to operate a pharmacy,

drug wholesaler, drug storage facility, or drug

manufacturing plant must include the following:

The name of the person responsible for

the operation of the facility, including any

licensed pharmacists responsible for its

operation.

The location of the facility to be licensed,

including physical street address.

A description of the activities to be performed

at the facility.

If a company with several facilities is seeking

licensure, a separate application must be

completed for each location desiring licensure.

There are several types of permits that may be

issued by the Board of Pharmacy. These include:

A permit to sell non-prescription medications

in the original package. Businesses that

hold this permit are not required to sell their

products at one fxed location.

A pharmacy permit can be issued and is

necessary to operate a full service pharmacy.

Limited service pharmacy permits may be

issued to pharmacies that are only practicing

a limited portion of pharmacy practice, such

as a closed-door pharmacy that only offers

patient counseling and does not dispense

medications.

Full service wholesale drug permits may be

issued to wholesalers that stock prescription

and nonprescription medications.

Nonprescription drug wholesale permits can

be issued to wholesalers that only want to

stock nonprescription medications.

Drug manufacturer permits may be issued

to facilities involved in the creation of

prescription and nonprescription drug

products.

A drug packager or pre-packager permit may

be issued to a person or business registered

with the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) and authorized by the FDA to change

the original manufacturers packaging of

a drug product to re-sell the repackaged

product to a business that is authorized to sell

repackaged medications.

A compressed medical gas distributor or

supplier permit can be issued to facilities

interested in selling or distributing

compressed medical gasses, such as oxygen.

Permits can be revoked if it is discovered that a

medical provider is receiving compensation from

a pharmacy for prescribing certain products. If a

permit-holders business is closing or otherwise

ceasing to operate, the permit should be

surrendered immediately, the Board of Pharmacy

must be notifed, and all drug products and

signage should be removed or destroyed.

Pharmacist licensure and continuing

education requirements for pharmacists

Pharmacists can obtain their licenses from the

Arizona Board of Pharmacy. To be eligible for a

pharmacist license, applicants must graduate from

an accredited school of pharmacy recognized

by the board, successfully complete a practical

experience program supervised by a licensed

pharmacist, pass the pharmacist licensure exam

and state jurisprudence exam, pay a pharmacist

application fee to the Board of Pharmacy, and be

of good moral character.

All pharmacists must renew their licenses every

other year, and all pharmacist licenses expire

on October 31. To be eligible for renewal,

pharmacists must complete three continuing

education units or CEUs (30 hours) every two

years, with at least 0.3 CEUs (three hours) on

the topic of pharmacy law. Proof of continuing

education completion should be retained for fve

years, and credits may not be carried over to the

next renewal period.

Failure to renew a pharmacist license by October

31 of a renewal year may result in additional

fees. Pharmacists who have not been practicing

pharmacy for more than one year must complete

a board-approved training program of 400 hours

before they are eligible to resume practice as a

pharmacist.

Pharmacists who serve as the pharmacist-in-

charge at a pharmacy must report this position

to the Board of Pharmacy. The pharmacist in

charge is considered the responsible manager of

the pharmacy. If this position is terminated, the

pharmacist must report this change to the Board

of Pharmacy as well.

Pharmacists who wish to serve as preceptors to

pharmacy interns must register for a preceptor

license with the Board of Pharmacy. These

pharmacists are responsible for practical

instruction of the intern, and are to act as a

teacher and mentor to the student. Preceptors are

also able to verify intern hours worked by the

pharmacy intern. To be eligible for a preceptor

license, the applicant must be a licensed

pharmacist with an unrestricted license and must

have at least one year of experience actively

working as a licensed pharmacist. Pharmacists

with preceptor licenses working in a community

setting may only be a preceptor to two pharmacy

interns per calendar quarter.

Pharmacy intern responsibilities

Pharmacy interns can work in a pharmacy

under a licensed pharmacist once they become

registered and licensed with the Board of

Pharmacy. To be eligible for an intern license,

applicants must be enrolled in an accredited

school of pharmacy recognized by the Board of

Pharmacy. Graduate intern licenses may be issued

to applicants who have graduated from a school

of pharmacy approved by the board.

A total of 1,500 intern hours must be recorded

with the Board of Pharmacy before an intern

is eligible for licensure as a pharmacist. No

more than 500 hours may be recorded per

quarter (three months). Pharmacy interns can

only register hours worked if working under a

preceptor, a licensed pharmacist registered with

the Board of Pharmacy with a preceptor license.

Intern hours may be registered after the beginning

of the frst year of professional pharmacy

education, and after the pharmacy intern receives

a Board of Pharmacy-issued intern license.

Intern licenses are issued for fve years, and

may be issued for an additional year with board

approval. Intern licenses are not eligible for

renewal as the intern license is used for students

studying to become pharmacists. Student who

do not complete their education within six years

must explain to the Board of Pharmacy that they

intend to continue working toward completing

their education and becoming a pharmacist for a

renewal to be issued.

The pharmacy intern may perform the following

tasks under the immediate supervision of a

licensed pharmacist:

Dispense and sell medications, medical

devices, and poisons to patients.

Compound medications.

Perform duties of a pharmacist, as long as a

licensed pharmacist directly supervises them.

Pharmacy interns are to be trained in the practice

of pharmacy during their intern hours worked.

This includes:

The manufacture and sale of medications and

medical devices.

Dispensing and compounding medications.

Clinical pharmacology.

Providing information on medications to

patients and health care providers.

Record keeping and completing federal and

state-mandated reports.

Maintaining compliance with the law.

Pharmacy technician responsibilities

Pharmacy technicians, pharmacy technician

trainees, and certifed pharmacy technicians must

be registered and licensed with the Board of

Pharmacy to work in a pharmacy, and the license

must be renewed every other year.

Before beginning work in a pharmacy, pharmacy

technicians and trainees must sign and date

a statement showing they have reviewed the

Board of Pharmacy regulations for pharmacy

technicians, the job description for their position

in the pharmacy, and the pharmacys handbook

of policies applicable to pharmacy technicians.

These policies should include information on

employer expectations for pharmacy technicians,

activities that technicians may perform, how

to report and avoid medication errors, how to

maintain confdentiality of patient information,

security procedures, federal and state regulations,

dispensing procedures, and maintaining the

pharmacy inventory and storage.

People interested in working as a pharmacy

technician must be 18 or older, possess a high

school diploma or GED certifcate, and be of

decent moral character. For interested persons

to be eligible to apply for a pharmacy technician

license, the person must complete a training

program for pharmacy technicians that meets

state-specifc standards, and take the Pharmacy

Technician Certifcation Board exam (PTCB

exam) and pass with a satisfactory score.

Pharmacy technicians in training must apply for a

pharmacy technician trainee license to complete

their training in a pharmacy.

Elite Page 5

After completing a pharmacy technician training

program and passing the PTCB exam, pharmacy

technicians may apply for a pharmacy technician

license with the Board of Pharmacy. The

license application must include demographic

information for the person applying, any felony

offense or drug-related offences committed or

pending, information on whether the person

applying has ever had a revoked or suspended

pharmacy license or a denied pharmacy

technician application, the pharmacy name and

location where the applicant will work, the

verifed signature of the person applying, the

date, and the license fees for the license issuance

and wall hanging license to be displayed in the

pharmacy.

The Board of Pharmacy will determine eligibility

for licensure and make a decision within seven

days of receiving the application. Once the

Board of Pharmacy issues a license number, the

pharmacy technician may begin working. Wall

licenses should be mailed within 14 days of

license number issuance.

Pharmacy technician licenses must be renewed

every other year, and renewal must be completed

by flling out a renewal form and including the

necessary renewal fees. All pharmacy technician

licenses must be renewed by October 31 of their

renewal year. If license renewal is not completed

by November 1, the pharmacy technicians

license will be suspended and a late fee will be

added to the renewal fee.

Pharmacy technicians may perform the following

tasks when working under the supervision of a

licensed pharmacist:

Accept approval of refll authorizations

from a prescriber or representative. The

approval may be accepted electronically or

verbally, and must include the prescribers

name, patients name, drug name, quantity,

additional reflls, and name of the prescribers

representative.

Enter information into a patients profle.

Document the prescription number and

dispense date on the original prescription

order.

Enter prescription information into a

patients fle to create a prescription label for

verifcation by a pharmacist.

Reconstitute powdered medications if

ingredients added are verifed by a pharmacist

before reconstitution, and the fnal product is

verifed after reconstitution.

Count out or pour medications into bottles for

verifcation by a pharmacist.

Pre-package medications for verifcation by a

pharmacist.

Prepare medication for dispensing in the

inpatient hospital setting for verifcation by a

pharmacist.

NOTE: Pharmacy technicians cannot record

new prescriptions called in by a prescriber.

This includes any changes made to a refll

prescription, because a reflled prescription

that has been changed is considered a new

prescription.

Technicians must wear a nametag with their name

and title while working as a pharmacy technician.

Pharmacy technician training programs may be

conducted at the pharmacy where the technician

will work, or off-site at a training school.

Training programs must teach the technician

the tasks they will be required to perform in

their employment and discuss the policies and

procedures and activities that may be completed

by a pharmacy technician as implemented by the

Board of Pharmacy. Technicians must be assessed

on their knowledge of these tasks and retrained if

they do not demonstrate competency.

The pharmacist-in-charge who is training the

pharmacy technician must keep a record of

the progress of the trainee and sign off on a

document when the technician has completed the

training program successfully. Documentation

of successful completion of the training program

must be saved for possible inspection by the

Board of Pharmacy, and a copy must be provided

to the technician as well.

Technicians who wish to compound prescription

medications must successfully pass a training

program onsite at the pharmacy where they are

employed, or off-site at a pharmacy technician

training school. The training program must

address the following guidelines:

The tasks the pharmacy technician will be

required to perform.

Preparation of the area to be used for

compounding of prescription medications.

Preparation of the products to be used in the

compounding of a prescription product.

Aseptic technique to be used for the

preparation of prescription products in a

sterile environment.

How to properly package and label

prescription products.

Proper cleanup of the medication

compounding area, including procedures for

hazardous waste cleanup.

The technicians training progress must be

documented by the pharmacist in charge, and

program completion must be recorded and signed

by the pharmacist in charge. Documentation of

the completion of training programs must be

maintained for possible inspection by the Board

of Pharmacy.

NOTE: Only pharmacy technicians who

have successfully completed a medication

compounding training program may compound

prescription medications for fnal verifcation by

a pharmacist!

Pharmacy technician continuing

education requirements

In Arizona, pharmacy technicians need to obtain

a license from the Board of Pharmacy to work in

a pharmacy. To maintain their license, technicians

must complete 20 hours of continuing education

every other year, with two hours on the topic of

pharmacy law, to be eligible for license renewal.

Proof of continuing education completion should

be retained for fve years, and credits may not be

carried over to the next renewal period.

NOTE: Address changes and changes in

employer for any licensed pharmacy employee

must be reported to the Board of Pharmacy

within 10 days.

Pharmacists administering immunizations

In the state of Arizona, pharmacists who

are certifed to give immunizations may

immunize adults as recommended by the adult

immunization schedule or international travel

recommendations issued by the U.S. Centers for

Disease Control. These immunizations may be

issued without a prescription.

Certifed pharmacists may immunize children

aged 6-18 years with fu immunizations or

immunizations necessary during a public health

emergency without a prescription order. Other

immunizations may be given with a prescription

order from the patients prescriber.

Pharmacists must be trained and certifed in

immunization delivery before they are eligible

to apply for a certifcate to immunize patients.

The training program must include the following

information:

Immunology and the immune response

involved in immunization of patients.

Names of available vaccines, dose, side

effects, immunization schedule, and how

immunity occurs with each available vaccine.

How to respond to emergencies that occur

from the administration of a vaccine,

including how to administer epinephrine or

diphenhydramine to slow the effects of an

allergic reaction to a vaccine.

How to administer intramuscular and

subcutaneous injections.

Proper record keeping requirements and

reporting requirements for adverse effects

and prescriber notifcation.

NOTE: The training program developed by

the American Pharmacists Association (APhA)

meets the requirements for immunization training

programs in Arizona.

Pharmacists who have passed the immunization

training program are eligible for an immunization

certifcate from the Board of Pharmacy as long

as they have a current unrestricted pharmacist

license in Arizona and have a current certifcation

in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Pharmacists must apply for their immunization

certifcate with the Board of Pharmacy and

receive board approval before administering

immunizations to patients in Arizona.

Graduate interns may administer vaccinations

after completion of a certifcation course

and certifcation by the Board of Pharmacy,

but only under the supervision of a licensed,

immunization-certifed pharmacist. Graduate

interns may also administer epinephrine or

diphenhydramine in an emergency situation

under the supervision of a licensed, certifed

pharmacist.

Once graduate interns or pharmacists are

certifed to administer immunizations, the

certifcation must be maintained with the Board

Page 6 Elite

of Pharmacy and kept in the pharmacy for review

by patients or the Board of Pharmacy if needed.

Immunization certifcations must be renewed

every fve years. To be eligible for renewal, a

renewal application must be sent to the Board of

Pharmacy including a current certifcate in basic

cardiopulmonary resuscitation and completion of

0.5 continuing education units (5 hours) on the

administration of immunizations.

Immunizations given must have accurate records

maintained at the pharmacy. Each immunization

given must have documentation that includes:

The patients name, address and birth date.

The date the immunization was given and the

injection site.

The name of vaccine given as well as the

dose, lot number, and expiration date.

The name and address of the patients

primary care physician.

The name of the pharmacist or graduate

intern who gave the immunization.

A record of consultation with the patient

that determined the patient was eligible for

vaccination.

The date and time vaccination information

was sent to the patients primary care

provider.

Consultation information given to the patient,

including the title and date of the vaccine

information sheet (VIS).

A copy of the parent consent form for

vaccines given to minors.

Certain vaccines require a prescription for a

pharmacist to immunize an adult. These include

the Japanese encephalitis vaccine, the rabies

vaccine, yellow fever vaccines, and typhoid

vaccines. After receiving a prescription order

for these vaccines, a pharmacist is allowed to

immunize the patient.

6

All other vaccines may

be administered to an adult patient without a

prescription, according to the recommendations

published by the U.S. Centers for Disease

Control.

Documentation of vaccinations given to patients

must be sent to the patients primary care

physician within 48 hours of immunization.

Records must be kept in a readily accessible

place for at least seven years for possible

inspection by the Board of Pharmacy.

Conclusion

Arizona state pharmacy laws dictate the

daily operations of pharmacies and pharmacy

employees. It is important to stay up-to-date on

new pharmacy laws that govern daily practice

to serve patients within the limits of the law and

obtain continuing education credits to maintain

licensure. Information on new pharmacy laws in

Arizona can be found on the Arizona Board of

Pharmacys website at http://www.azpharmacy.

gov/. A copy of the current Arizona state

pharmacy law book can be found at http://www.

azpharmacy.gov/pdfs/law%20book%208-9-2012.

pdf.

References

1. Arizona State Board of Pharmacy. Prescriptive Authority of Health Professionals in

Arizona. February 2013. Accessed at http://www.azpharmacy.gov/pdfs/prescriptive%20

authority%20chart%20(02-2013).pdf on July 10, 2013.

2. Arizona Regulatory Board of Physician Assistants. FAQs: Information Regarding PA

Prescribing Changes. Accessed at http://www.azpa.gov/FAQ/PAPrescribingFAQ.aspx

on July 12, 2013.

3. Arizona State Board of Pharmacy. Arizona State Board of Pharmacy Revised Statue.

August 9, 2012. Accessed at http://www.azpharmacy.gov/pdfs/law%20book%208-9-

2012.pdf on July 10, 2013.

4. Berman, Suzi. Tamper Resistant Prescription Pads Memo. April 27, 2012. Accessed

at http://www.azahcccs.gov/commercial/Downloads/PharmacyUpdates/TRPP_

Memo_4_27_2012.pdf on July 14, 2013.

5. Glendale Police Department Pseudoephedrine. Accessed at http://www.glendaleaz.

com/police/pseudoephederine.cfm on July 13, 2013.

6. Arizona State Board of Pharmacy. Immunizations or Vaccines Requiring Prescriptions

for Pharmacist Administration. Article 13, Section R9-6-1301. Effective October 5,

2009. Accessed at http://www.azpharmacy.gov/pdfs/R9-6-1301VaccineList.pdf on

July 14, 2013.

OVERVIEW OF

ARIZONA PHARMACY LAW

Final Examination Questions

Choose the best answer for questions

1 through 5 and mark your answers on the

Final Examination Sheet found on page 63

or complete your test online at

www.elitecme.com.

1. How many members of the Arizona Board

of Pharmacy are pharmacists?

a. Nine.

b. Six.

c. Two.

d. One.

2. A prescription for oxycodone, a Schedule

II controlled substance, is brought to the

pharmacy to be flled. For how long is this

prescription valid?

a. One year from the written date.

b. Six months from the written date.

c. Six months from the frst fll date.

d. Ninety days from the written date.

3. How long must prescription hard copies be

kept in a readily accessible area?

a. Two years.

b. Three years.

c. Seven years.

d. Nine years.

4. How many hours of continuing education

must be completed by a pharmacy

technician every other year?

a. 15 hours.

b. 2 hours.

c. 20 hours.

d. 30 hours.

5. Which of the following vaccines requires a

prescription to be administered to an adult

patient?

a. Tetanus.

b. Herpes zoster.

c. Infuenza.

d. Japanese encephalitis.

RPTAZ02AZE13

Elite Page 7

CHAPTER 2

ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUG THERAPY FOR

PHARMACY PROFESSIONALS

(3 CONTACT HOURS)

By Katie Ingersoll, RPh, PharmD, and Staff Pharmacist

for national chain

Author Disclosure: Katie Ingersoll and Elite

Professional Education do not have any actual or

potential conficts of interest in relation to this lesson.

Universal Activity Number (UAN):

0761-9999-13-243-H01-T

Activity Type: Knowledge-based

Initial Release Date: July 30, 2013

Expiration Date: July 30, 2015

Target Audience: Pharmacy Technicians in a

community-based setting.

To Obtain Credit: A minimum test score of 70 percent

is needed to obtain a credit. Please submit your answers

either by mail, fax, or online at www.elitecme.com.

Questions regarding statements of credit and other

customer service issues should be directed to 1-888-

666-9053. This lesson is $15.00.

Educational Review Systems is accredited

by the Accreditation Council of Pharmacy

Education (ACPE) as a provider of

continuing pharmaceutical education. This

program is approved for 3 hours (0.3

CEUs) of continuing pharmacy education credit. Proof

of participation will be posted to your NABP CPE

profle within 4 to 6 weeks to participants who have

successfully completed the post-test. Participants must

participate in the entire presentation and complete the

course evaluation to receive continuing pharmacy

education credit.

Learning objectives

! Defne major depression.

! Describe the different types of depression.

! Discuss the incidence and prevalence of

major depression.

! Identify the signs and symptoms of major

depression.

! Discuss possible causes of major depression.

! Explain how major depression is diagnosed.

! Identify the classifcations of drugs used to

treat depression.

! Explain the action of each classifcation of

antidepressant drug therapy.

! Describe the side effects of each classifcation

of antidepressant drug therapy.

! Identify herbs used in the treatment of

depression.

! Explain the potential reactions when using

herbs for the treatment of depression.

! Summarize important considerations for

patient education.

Introduction

Nicole is a pharmacy technician who works

in a large pharmacy that is part of a major

drugstore chain. Several people approach the

pharmacy entrance. She recognizes 35-year-

old Mr. Davidson, who had a prescription flled

for antidepressant medication last week. His

wife and mother accompany him. His mother

appears impatient and angrily tells him, I

dont understand this depression business.

Everybody feels sad sometimes, but you just have

of depression will have another one.

25

After

a patient experiences a second episode of

depression, there is a 70 percent chance that

the depression will return.

24

2. Recurrent depression: Two or more

depressive episodes occur, separated by at

least two months of normal or near-normal

functioning.

11

3. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD): Changes

in mood in persons who are depressed may

be related to the seasons of the year. Patients

who experience season-related depression are

usually depressed during the fall and winter

and feel better during the spring and summer.

It is hypothesized that SAD is caused by a

reduction in the brains melatonin secretion,

which is triggered by sunlight. Since there

is less sunlight during the fall and winter,

SAD is more prevalent during these months.

However, there have been rare reported cases

of SAD occurring during the spring and

summer.

10

Some patients experience only one episode of

major depression and never have a recurrence

of the problem, while others may experience

multiple episodes. Still others may suffer chronic

depression that lasts a lifetime. It is not possible

to determine whether one episode of major

depression will develop into a lifetime condition

for each patient.

4,24,27

Incidence and prevalence of major

depression

Mental illness, defned as diagnosable mental

disorders, causes more disability in developed

countries than any other group of illnesses,

including cancer and cardiac disease. In fact, it

is estimated that 25 percent of all adults in the

United States will develop at least one mental

illness during their lives.

1

Depression is one of

the most common mental illnesses, affecting

nearly 18 million Americans, or one out of every

six people.

4,8

Therefore, it is likely that health

care professionals, at some point in their careers,

will work with patients who are experiencing

depression.

The number of reported cases of depression has

been increasing every year since the early 20th

century.

Depression alert! The incidence of depression

may be much higher than actually reported.

It is estimated that only half of all persons

who meet the criteria for diagnosis of major

depression (according to the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.)

request treatment. This makes it very diffcult

to accurately determine the true incidence of

depression.

8

Culture and socioeconomic conditions play a

signifcant role in the reporting and treatment

of depression. In some cultures and countries,

mental illness may not be openly discussed or

acknowledged. For example, in Eastern countries,

depressive symptoms are often reported as a

loss of energy or various types of pains rather

than a mental health issue.

8

It is important that

to get over it. You dont need medicine. Mrs.

Davidson looks anxiously at her husband and

asks her mother-in-law to help her make some

purchases. After the two women walk away, Mr.

Davison becomes tearful and shakes his head.

This medicine isnt working. Ive been taking

it for over a week now and theres no difference.

I cant take feeling like this anymore. Im just a

weakling, like my mother says. Nicole is very

concerned. She gently tells Mr. Davidson, You

are not a weakling. Depression is an illness that

can be treated with your medication, but it may

take time for you to start to feel a difference.

Please sit down. I am going to have the

pharmacist come and talk to you about how your

medicine works.

Fortunately for Mr. Davidson, an alert,

knowledgeable pharmacy technician was able

to initiate actions that will help him. Nicole

knows that depression is not something one

just gets over and that it can take weeks for

antidepressants to produce therapeutic effects.

2,9,19

Therefore, Nicole has taken the appropriate steps

to ensure Mr. Davidsons safety and help him get

the most beneft from his medication.

Being able to help Mr. Davidson and other

patients with major depression requires not

only knowledge of antidepressant drugs, but

also knowledge of major depression disorder

as well. Causes, contributing risk factors, and

presenting signs and symptoms are all issues

pharmacy technicians must be aware of. Such

knowledge helps to provide patients with the

best possible care and to help them achieve the

best possible outcomes. Pharmacy technicians

who are knowledgeable of the nuances of major

depression will put themselves in a better position

to not only serve their patients and attend to their

needs as they arise, but also prevent medication

errors and enhance patient care.

This course will discuss the defnition and

diagnosis of major depression, its prevalence,

signs and symptoms, and major causes of this

condition. A thorough discussion of available

treatments for major depression will be discussed

as well, including a description of the major drug

classes, drugs in each class, side effects, and

major drug interactions.

What is major depression?

Major depression, also referred to as unipolar

disorder, is a disorder characterized by persistent

feelings of sadness and worthlessness, anxiety,

low self-esteem, diffculty concentrating, and

lack of pleasure or no interest in normal daily

activities.

4,21

There are three types of depressive episodes.

These are single, recurrent and seasonally

patterned.

10

1. Single depressive episode: A person

experiences a limited episode of depression

that occurs and ends within a fxed period of

time. After this one episode, the person does

not experience depression again.10 However,

it is important to know that 50 percent to 60

percent of persons who have one episode

Page 8 Elite

health care providers do a careful and thorough

history and physical, including mental health

assessments, when evaluating patients health and

well-being.

Major depression affects all racial, ethnic and

socioeconomic groups. It is twice as common

in women as in men. However, the incidence of

depression in men increases with age, and the

incidence of depression in women decreases with

age. There is also a higher risk of depression in

patients with a family history of the disorder.

Major depression is 1.5 to 3 times higher in frst-

degree relatives (e.g., parents, siblings, children)

than in the general population. The incidence of

major depression is highest in single people and

in people who are divorced.

24

Depression occurs in all age groups, but its

onset is commonly frst identifed between the

ages of 24 and 44. The incidence of depression

and suicide among teenagers increases every

year. Experts hypothesize that this increase is

due to feelings of pressure to meet expectations

of parents and peers as well as self-esteem

problems.

7

Signs and symptoms of major depression

Marjorie is a 32-year-old assistant professor

of American literature at a large, prestigious

university. She is highly respected by her

colleagues and students and has published

several critically acclaimed books. She is

married and the mother of a 5-year-old daughter.

Her marriage had always been happy and her

daughter a source of great joy to both her and her

husband. However, for the past month, Marjorie

has complained that she feels exhausted and

emotionally drained. Marjorie spends most of

her time at home sleeping, and no longer has any

interest in spending time with her husband and

daughter. Her students are beginning to complain

that she has no interest in them or in teaching.

Marjories family and work colleagues are

concerned and urge her to see a doctor. Marjorie

responds by saying, What good will that do?

Theres nothing to enjoy about life anymore, and

a doctor isnt going to help me feel any better.

Marjorie seems to be experiencing a major

depressive episode.

The primary exhibiting symptoms of a major

depressive episode include:

4,24

Feelings of sadness, hopelessness and

worthlessness.

Disturbances in sleep patterns (either sleeping

too much or being unable to sleep).

Decreased attention to activities of daily

living.

Lack of participation and enjoyment in

previously pleasurable activities.

Weight loss or gain.

Agitation.

Fatigue.

Decreased self-esteem.

Diffculty concentrating or making decisions.

Lack of interest in sexual activity.

Suicidal thoughts.

Some patients with severe depression (about 9

percent of those effected) may have psychotic

symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions.

These symptoms can be severe and may indicate

another mental health disorder, or simply an

adverse reaction to major depression. These

patients should be thoroughly evaluated by a

mental health professional.

24,27

Depression alert! Some patients with depression

may feel that life is no longer worth living and

attempt to take their own lives. About twice as

many women compared to men attempt to commit

suicide, but men who attempt suicide are more

likely to succeed in the attempt.

4

Suicide often

occurs just as depression begins to lift (e.g., after

antidepressants start to take effect). This may be

because of a lessening of the fatigue and inability

to concentrate associated with depression. As

the depression begins to lift, the patients energy

level and ability to concentrate increases, and

the ability to plan and implement a suicide

plan also increases. This is especially common

in adolescents and young adults, and a black

box warning on many antidepressants warns

caregivers to monitor patients closely for this

reaction.

2,4,24,27

Causes and diagnosis

Charlotte is a business manager who works

at a large university-affliated medical center.

She is having lunch with her best friend Anna,

a pharmacy technician with many years of

experience in a variety of health care settings.

Charlotte has had several recurrences of major

depression over a period of several years. It is

likely that she will need to take antidepressant

medication indefnitely. Charlotte is tearful and

confesses that her husband and teenage children

are starting to question why she is still taking

medication. My husband and the kids say Im

just babying myself. They keep telling me that I

have a good life and dont seem depressed. They

want me to stop taking medication. They say there

is no real reason for me to become depressed

again. Im beginning to wonder myself if I need

this medication. What really causes depression

anyway? Its just something emotional, isnt it?

I mean, theres no physical reason for me to

become depressed, is there? Anna responds by

explaining that there are a number of possible

causes of depression. She wants to help Charlotte

get the necessary patient education about major

depression, its possible causes and its treatment.

The exact cause of depression is not completely

understood, but research indicates that a

combination of factors, including family

history, psychosocial issues, concurrent physical

conditions, and biochemical factors infuence its

development. For example, depression may be

secondary to some medical conditions, such as

endocrine disorders and neurologic diseases. It

may follow a traumatic event, such as the death

of a loved one or divorce. Some medications,

such as anti-hypertensives and anti-parkinsonian

drugs, may trigger depression.

4,6,7

It is important

that health care professionals be aware of the

various factors that can lead to the development

of a major depressive episode.

As in the case of Charlotte in the preceding

scenario, patients need to be provided with

information about the possible causes and

risk factors of depression. Without such

education, patients may be tempted to belittle

the seriousness of major depression and to

discontinue necessary treatment. Discontinuing

antidepressant medications abruptly can cause

dangerous side effects and can put the patient at

risk of harming himself or herself. The following

factors may trigger a depressive episode or

contribute to a diagnosis of chronic depression.

Psychosocial stressors

Psychosocial stressors can trigger depression.

Depression is more common in patients who

have a history of signifcant trauma, such as

death of a loved one, divorce, physical abuse,

sexual abuse, or loss of income. Stress in the

workplace or home life can also contribute to

the development of depression.

4,7,27

The patients

history and a thorough discussion with the patient

about depressive triggers may pinpoint a specifc

bereavement or stressor that has triggered the

depression.

Physical medical conditions

Depression may occur secondary to a number of

physical medical conditions, such as:

4

Malignancies.

Endocrine disorders.

Neurologic diseases.

Bacterial infections.

Cardiovascular disorders.

Gastrointestinal disorders.

Anemias.

Persons dealing with physical illness should

also be monitored for signs and symptoms of

depression. Physical illness is a stressful state and

may very well trigger a depressive episode.

Medications

Gerald is diabetic. His disease has been well

controlled for many years by diet and oral anti-

diabetic medication. Gerald also suffers from

recurring episodes of major depression. His

physician believes that Geralds anti-diabetic

medication may be contributing to his depression.

Various medications used to treat physical and

other mental health illnesses can also cause

depression. It is important that pharmacy

personnel are aware of this potential side effect,

and pharmacists should include ways to monitor

for depression as part of patient education.

Patients who experience depression as a side

effect of other medications should discuss

their symptoms with their medical provider

immediately, before symptoms become severe.

Medications that may lead to depression include:

4

Anti-hypertensives.

Psychotropics.

Opioid and non-opioid analgesics.

Medications used to treat Parkinsons disease.

Cardiovascular medications.

Steroids.

Elite Page 9

Oral anti-diabetic drugs.

Cimetidine.

Chemotherapeutic drugs.

Depression alert! Substances such as alcohol

and illegal drugs can also cause depression.

4

Family history

Research shows that people whose parents suffer

from depression are more likely to develop

depression themselves. A patient with one parent

who has depression has a 27 percent chance of

developing a mood disorder, and if both parents

have a history of depression, the chance increases

to 54 percent.

7

As previously noted, major

depression is 1.5 to 3 times higher in frst-degree

relatives (e.g., parents, siblings, children) than in

the general population.

24

Biochemical factors

Although the exact biochemical infuence on the

development of depression is not known, most

researchers believe that some neurotransmitters,

particularly norepinephrine and serotonin, are

decreased in patients with depression. Under

normal conditions, neurotransmitters are released

to link with specifc neural receptors. If an

inadequate amount of neurotransmitters are

released or if the number of neural receptors is

decreased, depression may occur.

24

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made based on a complete history

and physical and the use of psychological

screening tests, such as the Beck Depression

Inventory.

4

A patient is diagnosed as having

major depression when he or she meets the

criteria identifed in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition. Some of

the criteria are:

4

A minimum of fve of the following

symptoms must have been present during the

same two-week period and must be a change

from the patients normal pattern of behavior

and functioning:

Depressed mood most of the day, nearly

every day.

Signifcantly reduced interest in or

pleasure in activities of daily living.

Signifcant loss or gain of weight when

not dieting.

Sleep disturbances, such as sleeping too

much or not being able to sleep.

Fatigue or energy loss.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

experienced almost every day.

These symptoms do not meet the criteria

for a mixed episode (when symptoms of

depression alternate with symptoms of

mania).

These symptoms signifcantly interfere with

the patients ability to function at work, at

home and in social situations.

These symptoms are not directly due to the

effects of a general medical problem or due

to substance abuse (such as illegal drugs).

Depression alert! The preceding criteria are not

all-inclusive. For complete diagnostic criteria,

refer to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders 4th ed.

4

The prevalence of depression makes it almost a

certainty that pharmacy technicians, no matter

their practice setting or specialty, will care

for persons who are currently experiencing

this disorder. Therefore, it is imperative that

all pharmacy technicians be knowledgeable

about the types of medications prescribed for

major depression, their actions, dosage, side

effects and potential adverse interactions. This

education program provides information about

the pharmacological interventions for major

depression, including herbal preparations.

Antidepressant pharmacology

Mrs. Adams has been taking antidepressant

medication for several years. Her physician

evaluates her on a regular basis, and believes

that she suffers from chronic depression. This

means that Mrs. Adams may need to take

medication for the rest of her life. When Mrs.

Adams comes to the pharmacy to have her

antidepressant prescription reflled, she asks the

pharmacy technician, How long is this going to

go on? I think I should stop taking these stupid

pills. I feel fne now. Mrs. Adams should be

referred to the pharmacist for appropriate patient

education on the nature of her depression as well

as the need to keep taking her antidepressant.

Prescription antidepressant medication is

the most common treatment intervention for

depression. About 80 percent of patients who take

antidepressants report an improvement in their

symptoms.

9

Treatment length varies among patients.

Treatment for an initial depressive episode may

last from six months to a year, and recurrent

episodes may require two years of treatment

with antidepressants. Chronic depression may

necessitate life-long treatment, as in the case of

Mrs. Adams in the preceding scenario.

9

It may take from one to eight weeks for

antidepressant medication to become fully

effective, depending on the dosage and the

patients response to the medication. Patients

should be thoroughly counseled on the time for

treatment to become fully effective, as this time

period is often diffcult for patients to cope with.

Drugs are generally prescribed initially at a low

dose, which is gradually increased according to

the patients tolerance and response to the drug.

Patients should be taught that therapeutic effects

are not immediately apparent. Sometimes the

antidepressant initially prescribed is ineffective,

and other drug options must be prescribed to

achieve the desired therapeutic effect.

2, 9

Drug alert! Patients on antidepressant

medication must be carefully monitored. In some

cases, antidepressants may increase the risk for

suicidal ideation, particularly in young adults

and children.

2,9,19

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

mandates that all antidepressants carry a warning

that some children, adolescents and young adults

may be at increased risk for suicidal ideation.

All patients, however, should be monitored

meticulously for any increase in depression or

unusual behavior, particularly during the frst few

weeks after antidepressant therapy is initiated.

2,13

Antidepressant medications include the

following:

2,9,19,24

SSRIs: Selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors.

Cyclic antidepressants.

Atypical antidepressants.

MAOIs: Monamine oxidase inhibitors.

SNRIs: Serotonin and norepinephrine

reuptake inhibitors.

Drug alert! Antidepressants are sometimes

prescribed to treat conditions other than

depression, such as panic disorder, post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety

disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and

premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

2,19

Age-related concerns

Antidepressant use in children and adolescents

requires especially careful monitoring. However,

many medications have not been studied or

approved for use with children. Researchers are

not sure how these medications affect a childs

growing body. Physicians often will prescribe

an FDA-approved medication on an off-label

basis for children even though the medicine is not

approved for the specifc mental disorder or age

group. Young people may have different reactions

and side effects than adults and are at somewhat

greater risk for suicidal ideation when taking

antidepressants.

There is a black box warning on antidepressants

that adolescents and young adults should be

closely monitored when starting antidepressants

because of the increased risk of suicidal attempts.

It is very, very important that parents and other

caregivers be taught to monitor children for

any signs that they are thinking of harming

themselves.

2,9,19

Because older people often have more medical

problems than other groups, they tend to

take more medications than younger people,

including prescribed, over-the-counter nutritional

supplements and herbal preparations. As a result,

older people have a higher risk for experiencing

adverse drug interactions, skipping doses, or

overdosing.

Older people also tend to be more sensitive

to medications and their side effects. For

example, dizziness can be a side effect of many

antidepressants. Young patients may be able to

handle this side effect without problems, but

it can put older adults at a higher risk of falls,

potentially causing injury. Even healthy older

people react to medications differently than

younger people because their bodies may process

drugs more slowly. So lower or less frequent

doses may be prescribed for older patients.

2,9,17,24

Sometimes memory problems affect older people

who take medications for mental disorders. An

older adult may forget his or her regular dose

Page 10 Elite

or take too much or not enough. A good way

to keep track of medicine is to use a seven-day

pillbox, which can be bought at any pharmacy.

At the beginning of each week, older adults or

their caregivers fll the box so that it is easy to

remember what medicine to take each day. Many

pharmacies also have pillboxes with sections for

medications that must be taken more than once a

day, and some pharmacies even offer services to

fll pillboxes for patients or package medications

in easy to use blister packs.

2,9,17,24

Pharmacy personnel should make it a point to

offer suggestions to help make it easier for older

patients (or patients of any age, for that matter)

to remember to take their medications as ordered.

They should not wait for patients to ask. Instead,

offer suggestions and initiate conversation about

ways to properly take mediations.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

(SSRIs)

The most commonly prescribed antidepressants