Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Above Dome

Uploaded by

reacharunk0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views1 pageljljljl

Original Title

EN(141)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views1 pageAbove Dome

Uploaded by

reacharunkljljljl

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

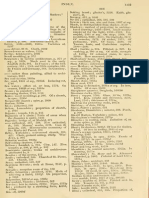

C,,,M.. II.

POINTED ARCH. 110

dome. On tlie exterior are two orders of Corinthian columns engaged in tlie wall, wliich

sui)))ort semicircular arches. In the upper order the columns are more numerous, inas-

niiicli as each arch below bears two columns above it. Over every two arches of the iip])er

oriier is a sharp pediment, separated by a pinnacle from the adjoining ones; and above the

pediments a horizontal cornice encircles the buiUling. Al)ove the second story a division

in the com])artments occurs, which embraces three of the lower arches

;

the se])aratior.

being ertected by piers triangular on the plan, crowned by ])innacles. Between these ])iers.

semicircular headed small windows are introduced, over each of which is a small circular

window, and thereover sharp pediments. Above these the convex surface of the dome

springs up, and is divided by twelve ribs, truncated below the vertex, and ornamented with

crockets. Between these ribs are a species of dormer windows, one between every two ribs,

ornamented v/ith columns, and surmounted each by three small pointed jiediments. The

total height is about 170 ft. The cupola is covered with lead and tiles; the rest of tlie

edifice is marble.

SO.'?. The extraordinary campanile, or bell tower, near the cathedral at Pisa, was built

about 1 174. It is celebrated from the circumstance of its overhanging upwards of thirteen

feet, a peculiarity observable in many other Italian towers, but in none to so great an extent

as in this. There can be no doubt whatever tliat the defect has arisen from bad foundation

and that the failure exhibited itself long before the building was completed

;

because, on

one side, at a certain height, the columns are higher than on the other ; thus showing an en-

deavour on the part of the builders to bring back the upper part of the tower to as vertical

a direction as was ])racticable, and recover the situation of the centre of gravity. 'Ihe

tower is cylindrical, 50 ft. in diameter, and 180 ft. high. It consists of eight stories of

columns, in each of which they bear semicircular arches, forming open galleries round the

story. The roof is flat, and the ujiper story contains some bells. The last of the grou]) of

buildings in Pisa is the Campo Santo, which, from its style and date (l'i7), is only men-

tioned here out of its |)lace in order to leave this interesting spot without necessity for further

recurrence to it. It is the public burying place of the city, and, whetlier from the remains on

its walls of the earliest examples of Giotto, and Cimabue, the beauty of its jiroportions, or

the sculjiture that remains about, is unparalleled in interest to the artist. It is a quadrangle,

40.'3 ft. in lengtli, 1 17 ft. in width, and is surrounded by a corridor 32 ft. in breadth. This

corridor is roofed, forming a sort of cloister with semicircular-headed windows, which were

at first simple apertures extending down to the pavement, but they have been subse<juently

divided into smaller apertures by columns, which, from the springing of the arches, branch

out into tracery of elegant design. The interior part of the <iuadrangle is open to the sky.

Some of the arches above mentioned were completed as late as the year 14G4.

The style of the transition to pointed art will be noticed in the section on PoiNrEu

Akchitkctuke at the end of Book I.

Sect. XV.

(a) ORIGIN or THE POINTED AKCII.

294. About the end ot the 12th and the beginning of the 13th century, a most singular

and important change took place in the architecture of Europe. The flat southern roof,

says Miiller, was su]ierseded by the high pitched northern covering of the ecclesiastical

edifices, and its introduction brought with it the use of the pointed arch, which was sub-

siuuted for the semicircular one : a necessary consequence, for the roo^' and vi-uits being

thus raised, the diameter of the whole could not lie jireserved without changing the entire

arrangement of the combination of forms. But we have great doubts on Holler's hypo-

thesis ;

it will, indeed, be hereafter seen we have a different belief on the origin of the pointed

arch.

'

Before we at all enter upon the edifices of the period, we think it will be better to

put the reader in possession of the different hypotheses in which various writers have in-

dulo-ed, relative to the introduction or invention of the pointed arch

;

and though we attach

very little importance to the discovery, if it could now be clearly established, we are, as our

work would be incomplete without the notice, compelled to submit them fjr the reader's

consideration.

295. 1. Some have derived this style frovi the hohj groves

of

the early Celts But we can

see no <round for this hypothesis, for it was only in the 14th and 15th centuries that ribs

between the groins (which have been compared to the small branches of trees) were intro-

duced ;

hence it is rather difficult to trace the similarity which its supporters contend for.

29fi. 2. That the stifle oriyinuted from htits made with twigs avd branches

of

trees intertwined.

An hvpothesis fancifully conceived and exhibited to the world by Sir James Hall, in

some very interesting plates attached to his work. ]\Ioller properly observes upon this

theory of twigs, that it is only in the buildings of the 15th and IGth centuries that the

supposed imitation of twigs appears.

You might also like

- Many Humour Who The May Two The TheDocument1 pageMany Humour Who The May Two The ThereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Now We Mark: Fig. 146. RorvncoDocument1 pageNow We Mark: Fig. 146. RorvncoreacharunkNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829No ratings yet

- The From MayDocument1 pageThe From MayreacharunkNo ratings yet

- ENDocument1 pageENreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Theory: Common Round WoodDocument1 pageTheory: Common Round WoodreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture, v. 2Document449 pagesByzantine and Romanesque Architecture, v. 2kosti7No ratings yet

- Arhitectura Bizantina Vol 2 - EnglDocument404 pagesArhitectura Bizantina Vol 2 - Englproteor_srlNo ratings yet

- Pointed.: On A "ADocument1 pagePointed.: On A "AreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Now of LaDocument1 pageNow of LareacharunkNo ratings yet

- Crown Make Named: Tlio - Se AllDocument1 pageCrown Make Named: Tlio - Se AllreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mound: Tlie L) Uililliig. IsDocument1 pageMound: Tlie L) Uililliig. IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- History Of: AkchitectuiveDocument1 pageHistory Of: AkchitectuivereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Geometry Construction and Structural Analysis of The Crossed Arch Vault of The Chapel of Villaviciosa in The Mosque of C RdobaDocument16 pagesGeometry Construction and Structural Analysis of The Crossed Arch Vault of The Chapel of Villaviciosa in The Mosque of C RdobaAltafNo ratings yet

- May The The: Tliat Tlil'IrDocument1 pageMay The The: Tliat Tlil'IrreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Gothic VaultsDocument13 pagesGothic VaultsDevyani TotlaNo ratings yet

- Gothic ArchitectureDocument138 pagesGothic ArchitectureYasmine Leoncio100% (2)

- PPT7.Gothic ArchitectureDocument45 pagesPPT7.Gothic ArchitectureHania Abdel RashidNo ratings yet

- Fiveordersofarch00vign PDFDocument136 pagesFiveordersofarch00vign PDFEugen IliesiuNo ratings yet

- A Chart Illustrating The Architecture of Westminster Abbey (1846)Document4 pagesA Chart Illustrating The Architecture of Westminster Abbey (1846)lotusfrogNo ratings yet

- GothicDocument5 pagesGothicJesus is lordNo ratings yet

- En (1016)Document1 pageEn (1016)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Wicn Who Hawksmoor, Own Many Mad Mary Lom-Name: C.i: Iu KDocument1 pageWicn Who Hawksmoor, Own Many Mad Mary Lom-Name: C.i: Iu KreacharunkNo ratings yet

- History Of: AilchitectulleDocument1 pageHistory Of: AilchitectullereacharunkNo ratings yet

- History Of: Allchltectulle. Rome Two RomeDocument1 pageHistory Of: Allchltectulle. Rome Two RomereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1057)Document1 pageEn (1057)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- ENDocument1 pageENreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Axialsystemsincompressionandtensionincludingsap2000 160304165516Document446 pagesAxialsystemsincompressionandtensionincludingsap2000 160304165516Sara RamliNo ratings yet

- En (1031)Document1 pageEn (1031)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- The The Much The Commonly::'a'2. Ill IsDocument1 pageThe The Much The Commonly::'a'2. Ill IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- HoaDocument79 pagesHoaStephanie Joy Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Notre DameDocument9 pagesNotre DameRaj MaistryNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829 by VariousDocument35 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 356, February 14, 1829 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Origin and Development of Crown Post Roof. Fletcher and SpokesDocument32 pagesOrigin and Development of Crown Post Roof. Fletcher and Spokeslittleshell69No ratings yet

- Gothic ArtDocument7 pagesGothic ArtDr.Tapaswi H M NICONo ratings yet

- The Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceDocument9 pagesThe Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceMokhtar MorghanyNo ratings yet

- One We WeDocument1 pageOne We WereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Pointed.: New MadeDocument1 pagePointed.: New MadereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Acoustics of Gol GumbazDocument12 pagesAcoustics of Gol GumbazAnkit100% (1)

- Architectural Reviewer All Subjects PDFDocument803 pagesArchitectural Reviewer All Subjects PDFsmmNo ratings yet

- History of ArchitectureDocument53 pagesHistory of Architecturekelvin realNo ratings yet

- Domestic Architecture 1700 To 1960Document22 pagesDomestic Architecture 1700 To 1960Antonio GalvezNo ratings yet

- History, Theory Criticism 4 - Unit 1Document45 pagesHistory, Theory Criticism 4 - Unit 1Hema GNo ratings yet

- Jilaii TlieDocument1 pageJilaii TliereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan.: Work Memoranda ManyDocument1 pageElizabethan.: Work Memoranda ManyreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Architectural Reviewer (All Subjects) PDFDocument525 pagesArchitectural Reviewer (All Subjects) PDFSteven John PadillaNo ratings yet

- Literary and Structural Analysis of The First Dome On Justinian's Hagia Sophia, ConstantinopleDocument13 pagesLiterary and Structural Analysis of The First Dome On Justinian's Hagia Sophia, ConstantinopleLycophronNo ratings yet

- Theory: of ArchitectureDocument1 pageTheory: of ArchitecturereacharunkNo ratings yet

- PantheonDocument2 pagesPantheonAlina A AlinaNo ratings yet

- Early and High RenaissanceDocument19 pagesEarly and High RenaissanceEnriquez Martinez May AnnNo ratings yet

- The Romanesque Germany Worms, Much The CampoDocument1 pageThe Romanesque Germany Worms, Much The CamporeacharunkNo ratings yet

- Script ReportDocument4 pagesScript ReportmoreNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 355, February 7, 1829 by VariousDocument33 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 13, No. 355, February 7, 1829 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- St. Peter's Basilica: Iron Tension RingsDocument30 pagesSt. Peter's Basilica: Iron Tension RingsAbishaTeslinNo ratings yet

- Ceollgk: Some WhoDocument1 pageCeollgk: Some WhoreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Roman: Tlie Hi'st Ill Ilie Its IsDocument1 pageRoman: Tlie Hi'st Ill Ilie Its IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Among: Made Among Aik AmountDocument1 pageAmong: Made Among Aik AmountreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document118 pagesChapter 1mrramaNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Supplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesDocument65 pagesSupplement To The Prospectuses and Summary Prospectuses For Investor Shares and Admiral™SharesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1460)Document1 pageEn (1460)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1454)Document1 pageEn (1454)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- NameDocument2 pagesNamereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1463)Document1 pageEn (1463)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Emergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014Document2 pagesEmergency Response Quick Guide MY: 2014reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1462)Document1 pageEn (1462)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1461)Document1 pageEn (1461)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1455)Document1 pageEn (1455)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1457)Document1 pageEn (1457)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1453)Document1 pageEn (1453)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1456)Document1 pageEn (1456)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1452)Document1 pageEn (1452)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1389)Document1 pageEn (1389)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1388)Document1 pageEn (1388)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1450)Document1 pageEn (1450)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1390)Document1 pageEn (1390)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1387)Document1 pageEn (1387)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Construction Cost Handbook Vietnam 2019 PDFDocument142 pagesConstruction Cost Handbook Vietnam 2019 PDFtrong caoNo ratings yet

- Truss DEtailDocument1 pageTruss DEtailjerick calingasanNo ratings yet

- Bus Terminal Cum Commercial Complex Docx LalitDocument3 pagesBus Terminal Cum Commercial Complex Docx Lalitlalit singhNo ratings yet

- Unit Weight of Tile With MortarDocument4 pagesUnit Weight of Tile With MortarzcvzxNo ratings yet

- Unit 528 Concrete Design Task 1Document14 pagesUnit 528 Concrete Design Task 1Shine AungNo ratings yet

- Pareena Coban Residences Gurgaon.J457641190Document4 pagesPareena Coban Residences Gurgaon.J457641190Bharat sharmaNo ratings yet

- CASA BATROUN 1ST BREEAM CERTIFIED BUILDING IN LEBANON - Nabih MezherDocument14 pagesCASA BATROUN 1ST BREEAM CERTIFIED BUILDING IN LEBANON - Nabih MezhernabihmezherNo ratings yet

- Construction ScheduleDocument13 pagesConstruction ScheduleBilal Ahmed BarbhuiyaNo ratings yet

- Fire Safety-1Document4 pagesFire Safety-1Sanjeev34No ratings yet

- Gerard Da CunhaDocument11 pagesGerard Da CunhaGenevieveNoronha100% (1)

- Hume Doors Frontier Barn Door SystemsDocument16 pagesHume Doors Frontier Barn Door SystemsedmondschanNo ratings yet

- Art of Concrete StructuresDocument9 pagesArt of Concrete StructuresMustafa UzyardoğanNo ratings yet

- Architectural Design-I (150101) : ITM UniversityDocument6 pagesArchitectural Design-I (150101) : ITM Universityanon_891354001No ratings yet

- Masters - Brief Rev01 - Low PDFDocument6 pagesMasters - Brief Rev01 - Low PDFJack GillbanksNo ratings yet

- Singly Reinforced Concrete Beam Design ExampleDocument16 pagesSingly Reinforced Concrete Beam Design Exampleyamen0% (1)

- Architect'S Letter of Intent: Re: Ratner Residence 6494 Allison Road Miami Beach, FloridaDocument2 pagesArchitect'S Letter of Intent: Re: Ratner Residence 6494 Allison Road Miami Beach, FloridaNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- Mdterm Comprehensive QuizDocument2 pagesMdterm Comprehensive QuizMac KYNo ratings yet

- Spatial Analysis: Bhammariya Well - Mahemdavad: Studio - IiDocument12 pagesSpatial Analysis: Bhammariya Well - Mahemdavad: Studio - IibnaNo ratings yet

- Hans Schefferlie PresentationDocument93 pagesHans Schefferlie PresentationLelethu Ngwena100% (1)

- Pile Estimate Excel FileDocument3 pagesPile Estimate Excel FileShakil AhamedNo ratings yet

- Adequacy of Materials For Civil WorksDocument25 pagesAdequacy of Materials For Civil Workshari vNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Shulenburg Design PortfolioDocument30 pagesJeffrey Shulenburg Design PortfoliojeffreyshulenburgNo ratings yet

- Harappan CivilizationDocument9 pagesHarappan CivilizationOlivia RayNo ratings yet

- PP1 Rule 7 Classification by Use or OccupancyDocument8 pagesPP1 Rule 7 Classification by Use or OccupancyTamika AguilarNo ratings yet

- Masonry Design and DetailingDocument21 pagesMasonry Design and DetailingKIMBERLY ARGEÑALNo ratings yet

- Akron Art MuseumDocument2 pagesAkron Art MuseumSimona MihaiNo ratings yet

- Penthouse Roof Framing PlanDocument1 pagePenthouse Roof Framing PlanJedan TopiagonNo ratings yet

- Culverts and Low Level CrossingsDocument3 pagesCulverts and Low Level CrossingsAbdykafy ShibruNo ratings yet

- Door and Windows ScheduleDocument1 pageDoor and Windows ScheduleKoreenNo ratings yet

- Jones Recital Hall RFQDocument46 pagesJones Recital Hall RFQDaniel BarrenecheaNo ratings yet

- Architectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsFrom EverandArchitectural Detailing: Function, Constructibility, AestheticsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- House Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetFrom EverandHouse Rules: How to Decorate for Every Home, Style, and BudgetNo ratings yet

- Building Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignFrom EverandBuilding Structures Illustrated: Patterns, Systems, and DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Fundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsFrom EverandFundamentals of Building Construction: Materials and MethodsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- A Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsFrom EverandA Place of My Own: The Architecture of DaydreamsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (242)

- Dream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallFrom EverandDream Sewing Spaces: Design & Organization for Spaces Large & SmallRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Loving Yourself: The Mastery of Being Your Own PersonFrom EverandLoving Yourself: The Mastery of Being Your Own PersonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Big Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!From EverandBig Bim Little Bim: the Practical Approach to Building Information Modeling - Integrated Practice Done the Right Way!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignFrom EverandTo Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (138)

- Martha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesFrom EverandMartha Stewart's Organizing: The Manual for Bringing Order to Your Life, Home & RoutinesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Carpentry Made Easy - The Science and Art of Framing - With Specific Instructions for Building Balloon Frames, Barn Frames, Mill Frames, Warehouses, Church SpiresFrom EverandCarpentry Made Easy - The Science and Art of Framing - With Specific Instructions for Building Balloon Frames, Barn Frames, Mill Frames, Warehouses, Church SpiresRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to LifeFrom EverandBiophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Urban Sketching Handbook: Understanding Perspective: Easy Techniques for Mastering Perspective Drawing on LocationFrom EverandThe Urban Sketching Handbook: Understanding Perspective: Easy Techniques for Mastering Perspective Drawing on LocationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Welcome Home: A Cozy Minimalist Guide to Decorating and Hosting All Year RoundFrom EverandWelcome Home: A Cozy Minimalist Guide to Decorating and Hosting All Year RoundRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- How to Create Love, Wealth and Happiness with Feng ShuiFrom EverandHow to Create Love, Wealth and Happiness with Feng ShuiRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval EuropeFrom EverandThe Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval EuropeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationFrom EverandThe Florentines: From Dante to Galileo: The Transformation of Western CivilizationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Cozy Minimalist Home: More Style, Less StuffFrom EverandCozy Minimalist Home: More Style, Less StuffRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (154)

- Measure and Construction of the Japanese HouseFrom EverandMeasure and Construction of the Japanese HouseRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Vastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingFrom EverandVastu: The Ultimate Guide to Vastu Shastra and Feng Shui Remedies for Harmonious LivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday DesignFrom EverandThe 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday DesignRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Problem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerFrom EverandProblem Seeking: An Architectural Programming PrimerRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Flying Star Feng Shui: Change Your Energy; Change Your LuckFrom EverandFlying Star Feng Shui: Change Your Energy; Change Your LuckRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)