Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rohingya Identity

Uploaded by

Derek3012290 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

114 views11 pagesThere was no such identity as 'Rohingya' known to the British Governments of either India until 1937 or of Burma after the separation from India on 1 April of that year. The presence of persons of Islamic faith in Arakan and in the whole of Burma has been recorded by the British in considerable detail. The census enumerator would have written 'Chittagonian' if alternative identities were offered, such as 'Kawtaw', '

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThere was no such identity as 'Rohingya' known to the British Governments of either India until 1937 or of Burma after the separation from India on 1 April of that year. The presence of persons of Islamic faith in Arakan and in the whole of Burma has been recorded by the British in considerable detail. The census enumerator would have written 'Chittagonian' if alternative identities were offered, such as 'Kawtaw', '

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

114 views11 pagesRohingya Identity

Uploaded by

Derek301229There was no such identity as 'Rohingya' known to the British Governments of either India until 1937 or of Burma after the separation from India on 1 April of that year. The presence of persons of Islamic faith in Arakan and in the whole of Burma has been recorded by the British in considerable detail. The census enumerator would have written 'Chittagonian' if alternative identities were offered, such as 'Kawtaw', '

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

1

The 'Rohingya' Identity - British experience in Arakan 1826-1948

9 April 2014

Derek Tonkin

I only recently discovered the Digital Library of India. Like a child let loose in a sweetshop, I

have been gorging myself on unrestricted historical candy. With the Census in Myanmar on

its way to completion, I looked to see how the British in their time had handled the issue of

the 'Rohingya' identity which is currently a matter of deep concern: there sadly appears to

have been a last minute change of heart by the Myanmar Government not to allow self-

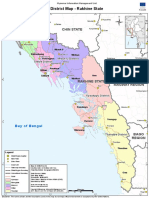

identification by Muslims as 'Rohingya', under the threat by Buddhists in Rakhine State to

boycott the census if that was permitted.

There is a very simple answer to the matter of British practice. There was no such identity as

Rohingya known to the British Governments of either India until 1937 or of Burma after the

separation from India on 1 April of that year. In the 122 years between their conquest of

Arakan in 1826 and Burmese independence in 1948, not a single reference to 'Rohingya' is

to be found in any British official report, regional gazetteer, census, legislation, private

correspondence or personal reminiscence. Even if such a self-identification had been made,

the census enumerator would have written 'Chittagonian' as they were under instructions to

do in both the 1921 and 1931 censuses if alternative identities were offered, such as

'Kawtaw', 'Barna', 'Babuji' or 'Magh'.

The presence of persons of Islamic faith in Arakan, and indeed in the whole or Burma, has

been recorded by the British in considerable detail and has in any case been attested by

writers and historians of all nationalities. It is not a matter of dispute.

One group which particularly attracted my attention in British records was what the 1901

Census described as the 'Arakan Muhammadans'. By the 1931 Census, now described as

'Arakan Mohamedans', their numbers totalled 51,615 compared to 252,152 'Chittagonians'

and 65,211 'Bengalis', in addition to 'Arakan Kamans' and 'Myedus' also resident in Arakan.

The 'Arakan Mohamedans' comprised 26,153 males and 25,462 females, an even balance

between the sexes as you would expect in a long-standing permanent community, while

'Chittagonian' males outnumbered females by two to one and 'Bengali' by three to one - a

ratio, I would have thought, which might favour polyandry rather than polygamy.

'Chittagonian' is hardly a racial, rather a linguistic and geographical designation. "It might be

argued that the figures for Chittagonians should be included in those for Bengalis", noted the

1931 Census Report, "but there is no harm done in giving separate figures for them." The

language spoken though by both groups was listed simply as 'Bengali'. In the 2014 Census,

the language spoken at home was not a question asked.

By means of that mysterious sympathy - the despair of the average European - which enables

Asiatics of all kinds to communicate with one another with apparent freedom on the veriest minimum

of a common vocabulary, the Burmese enumerator has, doubtless, despite his ignorance of the aliens

tongue, generally succeeded in making his native of India understand that what he wished to ascertain

was his Zat or caste. Paragraph 157 - 1901 Burma Census Report edited by C C Lowis,

Census Superintendent

2

The 'Arakan Muslims', as I shall call them, mostly resided in Akyab (Sittwe) District, but they

were also found further south in Kyaukphyu (1,597) and Sandoway [Thandwe] (1,658). In

his report on Indian Immigration released in 1940, Financial Secretary James Baxter said

that there was indeed "an Arakanese Muslim community settled so long in Akyab District

that it has for all intents and purposes to be regarded as an indigenous race." Baxter noted

that these Muslims commonly spoke the language of their ancestors among

themselves, although they used Burmese in writing.

The 1901 Census report referred to a group of Arakan Muhammadans who had been

"fetched from Arakan" as prisoners when the Kingdom of Arakan fell to Burman forces in

1785. They were eventually granted lands and allowed to settle around Mandalay. Their

descendants were to be found in the village of Bono (situated west of Meiktila) and also in

Taungmyin (in Rakhine State, to which they had presumably returned). These would

undoubtedly be the people whom the polymath Dr Francis Buchanan - medical practitioner,

botanist, linguist, geographer, gazetteer and traveller - had interviewed when he

accompanied a mission in 1785 to the Court of Ava, reporting in an article in 1799 on the

languages of the Burma Empire in a learned journal 'Asiatick Researches' that these were

Muslims who "have been long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves 'Rooinga', or

natives of Arakan".

This word 'Rooinga' would appear to mean no more than 'Arakaner' - a geographic locator

rather than an ethnic designation. It would seem to be derived from one of the many Bengali

names used to describe Arakan. As Buchanan put it in his 1798 "Account of a Journey in

South East Bengal": "Various parts of the hills are inhabited by Mugs [Rakhine] from

Rossawn, Rohhawn, Roang, Reng or Rung, for by all these name is Arakan called by the

Bengalese". Buchanan went on to say: "These people left their country on its conquest by

the Burmas [i.e. Burmans], and subsist by fishing, Boat building, a little cultivation, and by

the Cloth made by their Women. They also build houses for the Mohammedan refugees, of

whom many came from Arakan on the same occasion, and settling among men of their own

Sect, are now much better off than their former Masters [the 'Mugs']."

In his voluminous writings for scholarly journals and independently, both before and after his

visit to the Court of Ava in 1785, not once did Buchanan refer a second time to Arakan

Muslims as 'Rooingas' which he would assuredly have done if the designation had any

currency in the region at the time, or found any favour with him personally.

In the absence of any British archival documentation over the 122 years of their stewardship

of Arakan, I can only conclude that 'Rohingya' is a designation which came into existence

and usage after the Second World War, although it cannot be totally excluded that it might

be connected to folkloric tradition unknown to the British. It is however most important to

note that it was a designation which the Myanmar Government itself quietly acknowledged

and even on occasions used, though only infrequently, in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

"That the Arakanese are being pushed out of Arakan before the steady wave of Chittagonian

immigration from the west is only too well known.....the Arakanese not having been

accustomed to hard manual labour for generations cannot and will not do it now; it has to be

brought home to him that if he will not do more for himself he must give way to the thrifty and

hard-working Chittagonian and his only reply is to move on. " Page 89 - Akyab Gazetteer 1917

edited by Deputy Commissioner R B Smart.

3

These occasions, which included permission for radio broadcasts in the local dialect, are not

in dispute and have been well documented.

We might ask whether the Arakan Muslims of yesteryear in Akyab were indeed the

descendants of the original Muslim residents of Arakan. This seems very likely. But where

are they today, after the vicious sectarian fighting which followed the Japanese invasion in

1942, the disruptions of the Second World War, the Jihadist Uprising which lasted from

1948 to 1961 and the massive exodus to Bangladesh first in 1978 and then in 1991, and

eventual repatriation? Are there any Muslim residents who can today provide historical

documentation and assert, in the style of President Kennedy: "Ich bin ein Arakaner"?

The international campaign to support the 'Rohingyas', as many but by no means all

Muslims in Rakhine State now style themselves, has been so successful that it has become

confrontational and thus counterproductive to any solution. Not for one moment do I

begrudge the Muslims of Arakan their right to choose their own self-identity and to register

this in any Census. This would in any case seem to be their right under generally accepted

international practice. But it becomes counterproductive when supporters claim that these

indigenous Muslims of Arakan have always called themselves 'Rohingya', for which there is

simply no credible historical evidence.

It is uncontested, and should in any case be self-evident to us all, that some Muslim

residents of Arakan could, if only they had the documentation, trace their ancestry back

several centuries, while most others, even if 'Chittagonian', have been in Myanmar for four or

more generations and so qualify in principle for citizenship, even under the much criticised

1982 Act. Unfortunately the debate, under external pressures, has descended into a sterile

confrontation in which 'Rohingya' insist that their designation is proof that they are an

indigenous race, while the Government for its part insists that this not the case. This debate

over the origins and relevance of the designation 'Rohingya' conceals the much more

important reality of the long historical presence of Muslim residents in Arakan.

Can there be any compromise between these two apparently irreconcilable positions, as

clearly neither side is likely to give way? The 'Rohingya' surely cannot hope to convert a

post-Second World War political label into an ethnic designation acceptable to the

Government. But equally might not the Government be persuaded to recognise that they

have in the past referred to particular Muslim residents of Rakhine State as 'Rohingya',

notably in the military administration of the Mayu Frontier District in northern Arakan which

existed between 1961 and 1964? Might not the Government be willing in the right

circumstances to accept the limited use once more of this previously acknowledged geo-

political designation?

"Eight Arakanese witnesses, seven of whom were members of the Legislature, maintained

that Chittagonian penetration in Arakan is steadily continuing and is resented not only by the

Arakanese proper but also by the settled Chittagonians..The view was expressed that it

was inadvisable to let Chittagonian immigration go unchecked as it contained the seeds of

future communal troubles. All the witnesses agreed that immigration from Chittagong should

be restricted." Paragraph 69 - Report on Indian Immigration 1940 presented by Financial

Secretary James Baxter.

4

If 'Rohingya' were felt to be a step too far, why not seek to modernise the 'Arakan

Muhammadan' of 1901?

A way out of the impasse needs to be negotiated. Rakhine politicians should be brought to

accept the historical reality about the continuous presence of Muslims in Arakan for a very

long time. An end should be brought to the nonsensical assertions of their supporters that

the 'Rohingya' are all illegal immigrants from Bengal.

But supporters of Rakhine Muslims overseas should at the same time acknowledge that the

particular designation 'Rohingya' had no serious historical validity prior to independence in

1948.

(Derek Tonkin, former British Ambassador to Thailand, Vietnam and Laos, is an advisor to Bagan

Capital Limited and Editor of Network Myanmar)

The 'Rohingya' Identity - Further Thoughts

Derek Tonkin

19 April 2014

I have received one or two expressions of disbelief about the conclusion I reached in my essay on 9

April 2014 (The Rohingya Identity The British Experience in Arakan 1826-1948) that the

designation 'Rohingya' was totally unknown to the British administration of Burma.

I willingly acknowledge that it is for populations themselves to decide their own identity, and if

particular Muslim communities in Northern Rakhine State in Myanmar today wish to identify

themselves as 'Rohingya', it is not for outsiders to argue that they should not do so. How long, after

all, does it take for a person to feel that he or she is a New Yorker, or a Londoner, or a New

Zealander, or for that matter an Arakaner (Rohinger)? It is nonetheless important that the historical

truth about Muslim communities in Arakan should not simply be swept under the carpet, especially

in their hour of need.

I have conducted research on the censuses completed by the British in Burma in 1872, 1881, 1891,

1901, 1911, 1921, 1931 and 1941 (although most of the detail relating to the 1941 Census was lost

during the war). Most of these reports can be read online at the Digital Library of India and each

report runs to several hundred pages. I can confirm that the designation 'Rohingya' does not appear

anywhere in these reports.

The 1921 and 1931 British Censuses of Burma were the first to attempt, not all that successfully by

their own admission, an analysis and record of ethnicity, based primarily on language rather than on

anthropology. By 1931, the British had identified no fewer than 19 major Muslim communities in

Burma, including five in Arakan, but 'Rohingya' was not among them. If the designation had existed,

the British would have wanted to know. There was absolutely no reason to keep it secret from them

or from anyone else.

Apart from these eight Census reports, from time to time regional 'gazetteers' were published in

Burma. Taken together with the Census reports, these documents highlight the presence in Arakan

of a number of indigenous Muslim communities, including the Kamans, Myedus and 'Arakaner

Mohamedans' (see Note below) , as well as more recent arrivals recorded as Chittagonians and

Bengalis.

The 1917 Akyab Gazetteer compiled by Deputy Commissioner R B Smart has an especially revealing

passage on pages 89 and 90 about Muslim residents in the Akyab District, which is the name given

by the British to the town and district of Sittwe and which encompassed the northern part of Arakan.

We read:

"The Mahomedans, who in 1872 numbered 58,255, had by the year 1911 risen to 178,647.

Many are men who come down for the working season only from Chittagong and are

included in the census returns, but are not, properly speaking, inhabitants of the country. In

1879 it was recorded that those who were bona fide residents, though recruited by

immigrants from Bengal, were, for the most part, descendants of slaves captured by the

Arakanese and Burmese in their wars with their neighbours.

"The Arakan kings in former times had possessions all along the coast as far as Chittagong

and Dacca, and many Mahomedans were sent to Arakan as slaves. Large numbers are said to

have been brought in by Min Raja-gyi [King of Arakan 1593-1612] after his first expedition to

Sundeep [Sandiva] and the local histories relate that in the ninth century several ships were

wrecked on Ramree Island and the Mussalman crews sent to Arakan and placed in villages

there.

"They differ little from the Arakanese except in their religion and in the social customs which

their religion directs; in writing they use Burmese, but amongst themselves employ

colloquially the language of their ancestors.

"Long residence in this enervating climate and the example set by the people among whom

they have resided for generations have had the effect of rendering these people almost as

indolent and extravagant as the Arakanese themselves. They have so got out of the habit of

doing hard manual labour that they are now absolutely dependent on the Chittagonian

coolies to help them over the most arduous of their agricultural operations, ploughing,

reaping and earthwork.

"Since 1879 immigration has taken place on a much larger scale and the descendants of the

slaves are resident, for the most part, in the Kyauktaw and Myohaung [Mrauk U] townships.

Maungdaw township has been overrun by Chittagonian immigrants. Buthidaung is not far

behind and new arrivals will be found in almost every part of the district. The later settlers,

who have not been sapped of their vitality, not only do their own labour but it not

uncommon to find them hurrying on their own operations to enable such as can be spared

to proceed elsewhere to add to their earnings by working as agricultural labourers, boatmen

or mill coolies."

Although the story about Ramree Island is probably little more than popular legend, the Gazetteer

identifies the two townships of Kyauktaw and Myohaung/Mrohaung/Mrauk U as the principal

localities where Arakaner Mahomedans had settled, indeed mostly resettled after seeking refuge in

Bengal in British India following the Burman conquest of Arakan in 1785, but returning to Arakan

soon after the British took control in 1826. These residents would indeed seem to be the 'original'

Muslim residents of Arakan before the influx of large numbers of labourers from Chittagong and

further afield in Bengal which started in earnest in the latter part of the 19

th

Century.

It is not all that clear to me yet, though others may know, what happened to these particular

indigenous Muslims at the time of the Japanese invasion in late 1941. The Kamans and Myedus are

thought not to have been persecuted by the Rakhine in the communal violence of 1942 and to have

stayed in their well settled localities. There is however evidence that many Arakaner Mohamedans

perished during this violence in March and April 1942 in the wake of the British retreat into

India. The two townships are listed in most accounts of the violence, which affected both Buddhist

and Muslim communities, with the Buddhists seeking sanctuary in the south and the Muslims in the

north of Arakan. Those Muslim residents of the two townships able to escape would have fled to

Maungdaw or into Bengal, but a few pockets seem to have survived to this day around Kyauktaw

and Mrauk U.

After the convulsions of the Second World War and the struggle for independence in both India and

Burma, the Muslim community of Northern Arakan, which consisted primarily (but not exclusively)

of Bengali immigrants, would seem to have taken up the mantle of the Arakaner Mohamedans and

sought to regularise their presence on a more permanent basis. Many of them had crossed quite

legally into, and taken up residence in Burma half a century or more previously, but some were still

only recent arrivals and may well have had Pakistani nationality. Writing for 'The Scotsman' on 18

May 1949, their special correspondent Michael Davidson in Sittwe noted that: "The great majority of

Arakan Moslems are said to be really Pakistanis from Chittagong, even if they have been settled here

for a generation. Of the 130,000 Moslems here, 80,000 are still Pakistani citizens."

I do not know the source of Davidson's information, but I have no reason to doubt that he believed

what he wrote. On the other hand, in his 'Burma Outpost' published in 1945 Anthony Irwin, who

fought with local Muslims in Northern Arakan against the Japanese in 1942 and 1943, expressed the

view that: "They are generally known as Bengalis or Chittagonians, quite incorrectly, and to look at

they are quite unlike any other product of India or Burma that I have seen. They resemble the Arab

in name, in dress and in habit..As a race they have been here for over two hundred years." British

administrators on the other hand with expertise of Burma had no doubt that in 1942 the populations

of Maungdaw and Buthidaung were overwhelmingly "Chittagonian", enigmatically abbreviated to

"CFs".

From 1946 a separatist, jihadist uprising had gripped Arakan and in support of their political

objectives, the 'Rohingya' myth was created. It gained some acceptance nonetheless with the

Burmese military and political leaderships in Rangoon, concerned to bring about a peaceful ending

of the jihadist revolt which lingered on until 1961, as well as to seek political alliances with the

Muslim community for the ruling political party, the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League, which in

April 1958 split into 'clean' and 'stable' factions. The designation 'Rohingya' became established

among the Bengali speaking community.

The fact remains though that it was a fiction when created in the late 1940s, even if internationally it

is now widely accepted as fact, though not by the greater majority of the Burmese people, who

understand the reality on the ground rather better than most.

For all these reasons, we need to be so careful when speaking of the right of self-identification. On

the one hand, the retiring UN Special Rapporteur Toms Ojea Quintana has said in the context of the

recent Census that: "Self-identification should constitute a pillar of the collection of ethnically

disaggregated data. It is related to respect for the rights of individuals to assert their own identity.

To deny self-identification is therefore a violation of human rights." On the other hand, we might

well ask whether self-identification which is based on a fiction and which may have been foisted on

an impressionable community desperately seeking citizenship might not also be a violation of their

human rights, even if they were willing accomplices. No wonder this fiction has set Buddhist against

Muslim in Rakhine State.

I have assembled a range of materials on the 'Rohingya' issue which includes under the section

"British Reminiscences and Official Reports" relevant extracts from the British census and gazetteers

quoted above. In most cases the full reports are available online from the Digital Library of India .

The UN Security Council was briefed on the situation in Myanmar on 17 April 2014 by UN Special

Adviser Vijay Nambiar. The troubles in Rakhine State were high on the agenda. The US and the

UK took the lead in expressing their serious concern over recent events. They were absolutely right

to do so. Both countries, though, tend to shoot from the hip; they were so very prompt to condemn

the reported massacres at Du Chee Yar Tan on 9 and 13 January 2014. Myanmar has responded by

issuing a 110 page detailed rebuttal of the allegations - and they have pointedly declined to issue a

full English translation, only a summary. I do not need to tell you why.

Derek Tonkin

Editor - Network Myanmar

www.networkmyanmar.org

Heathfields, Berry Lane, Worplesdon, Guildford, Surrey GU3 3PU

Tel + 44 (0)1483 233576 - Mobile + 44 (0)7733 328832 - Email d.tonkin@btinternet.com

Note: From the 1921 Census of Burma: The Arakanese Buddhists in Aykab asked the Deputy Commissioner

there not to let the Arakanese-Mohamedans be included under Arakanese in the census. The instruction issued

to enumerators with reference to Arakanese-Mohamedans was that this race-name (in Burmese Yakaing-kala)

should be recorded for those Mohamedans who were domiciled in Burma and had adopted a certain mode of

dress which is neither Arakanese nor Indian and who call themselves and are generally called by others

Yakaing-kala ['Rakhine foreigner', to which Francis Buchanan first alluded in 1799].

The 'Rohingya' Identity: Arithmetic of the Absurd

Derek Tonkin

9 May 2014

I had it coming to me. Rohingya Bloggers have sought to demolish my recent presentation of the

British experience in Arakan. It is not merely that I am a dolt and a moron, but so too it seems were

all those British administrators who sought to depict in gazetteers and censuses the bewildering

kaleidoscope of ethnic diversity which they found in the country which Britain had conquered.

U Kyaw Min, who was only released from prison in January 2012, has a brilliant pedigree as a fighter

for freedom and democracy, a former member of the Committee Representing the People's

Parliament during the dark days of the military regime and currently Chairman of the Democracy and

Human Rights Party. In a recent article, after a preliminary skirmish to knock me off balance with a

barrage of punches and a swipe at my "attempt to appease his Myanmar friends in his working

environment" (I live and work in rural Surrey with no Burmese for miles, apart from a moggy or two),

he delivered the coup de grace with these words:

"So called Bengali or Chittagonians in British census were mostly foreigners. Except business related

persons and official staffs most of them were seasonal labourers, who did not bring their spouses.

These foreigners were also included in British censuses. Professor Dr. Than Tun named them as

floating population. Once the working season is over, they returned to their native land. Rohingya

has nothing to do with them.So called Chittagonian immigrants never took permanent

settlement, only natives who formerly left Arakan came back and settled in their original places."

Well, that puts me in my place, I suppose. When Deputy Commissioner RB Smart for Akyab District

(which then covered the entire northern region of present-day Sittwe and Maungdaw Districts)

recorded in his 1917 Gazetteer for Akyab that: "Maungdaw township has been overrun by

Chittagonian immigrants. Buthidaung is not far behind and new arrivals will be found in almost every

part of the district", he must have been suffering from another bout of malaria which brought on

hallucinations. Census Superintendents SG Grantham (for the 1921 Census) and JJ Bennison (for the

1931 Census) must have been in similar physical or mental turmoil when they both failed to realise

that reports compiled by census enumerators of hundreds of thousands of Chittagonians and

Bengalis now permanently resident in Akyab District were all pure fantasy.

Financial Secretary J Baxter, no doubt likewise afflicted by some incurable Burmese malaise, noted in

his 1940 Report on Indian Immigration that in the 1931 Census no less than 82.43% of all 186,327

Chittagonians and 15,586 Bengalis in Akyab District gave Burma as their place of birth, which could

only mean, if U Kyaw Min is correct, that as soon as they could walk they must have moved to

Chittagong in order to qualify as seasonal labourers in future years in the land of their birth.

Somehow, I doubt that this was the case. It is neither rational not logical. Reason and logic though

have little relevance to this debate, which as the dantonesque Maung Zarni told the recent London

School of Economics conclave on the Rohingya question, is all about deeply passionate research, but

for the cause rather than the truth, not any arid dispassionate concern for accuracy based on

historical record.

I have searched in vain for census traces of the hundreds of thousands of 'Rohingyas' alleged to have

been invisibly resident in British Burma. To be fair, U Kyaw Min agrees with me that no one will find

any trace: "True", he says, "quite correct. But he goes on to say: Then what about some present

day Rakhine state ethnic peoples: Mramagyi and Dai-net who are also not found in British

censuses?" But, with respect, these two minority groups of a few thousand people only were so tiny

that they hardly compared with the hundreds of thousands of Muslims now claiming to be

'Rohingyas'. In any case, U Kyaw Min should know that the "Daingnet" (to give the British spelling)

are designated 'F4' under the Suk(Lui) Group in both the 1921 and 1931 Race Tables as resident in

Akyab District, and a whole paragraph is devoted to them in RB Smart's Gazetteer, while the

Mramagyi, mostly a Bengal-resident minority which migrated from Arakan to Bengal some years

before the Burmans arrived in 1785, are the subject of an article by Francis Hamilton in the

Edinburgh Journal of Science in 1824. In British Burma it seems likely that they were included in the

Census variation "Mranma" or "Myamma" which appear alongside the more normal "Mranma" and

"Myanma", with the suffix -gyi added to denote family origin.

I will not take you sentence by sentence through the article by U Kyaw Min, but I have sent him two

kindly letters hoping to establish a correspondence. He has yet to respond.

In Article 19 of the Indo-Burma Agreement of 1941, the British Government of Burma recognised

that "Indians who are born and bred in Burma, have made their permanent home and regard the

future of their families as bound up with its interests are entitled to be regarded as having

established a claim, if they wish to make it, to a Burma domicile, and therefore to the benefit of the

Section 144 of the Burma Act 1935", which guaranteed full rights and privileges to any person

domiciled in Burma. The Chittagonians and Bengalis of Arakan, who were born in Burma, thus

became assured like other qualified Indians of their right to permanent domicile. But the war

intervened and what happened after 1942 is another story.

In British eyes, domiciled Chittagonians and Bengalis merited full citizenship in an independent

Burma. But it seems to me that the 'Rohingya' of today have only damaged their cause by denying

that they have any connection at all with those Chittagonians and Bengalis who became permanent

residents of Burma from the early part of the last century, at a time when seasonal labour was, as

the 1911 Census recorded, already in serious decline and by 1934 was in the region of only 20,000

annually, according to the Commissioner for Arakan Division.

In any case, if the 'Rohingya' of today are not the 'Chittagonians' of yesterday, what has happened to

the more than 200,000 or more Chittagonian/Bengali souls who were permanently resident in

Burma in the 1930s? Have they simply disappeared into thin air, as it were, while coincidentally a

broadly equal number of persons has emerged from obscurity, indeed total invisibility during British

Burma, to take their places as Rohingyas, occupying the same townships and village tracts, but

claiming to be in no way related to them? Are we, in psychoanalytical terms, face to face with a case

of mass hallucinatory reincarnation contrived by the alter ego or doppelgnger concept?

In support of his remarkable claim, U Kyaw Min quotes from a book by Anthony Irwin who fought for

several months alongside "these Mussulman Arakaners" who, Irwin wrote, "were "generally known

as Bengalis or Chittagonians, quite incorrectly..As a race they have been here for over two hundred

years". Captain Irwin was the son of General Noel Irwin, Commander for a time of the 'Eastern Army'

in India. He arrived in India having no experience of Burma whatsoever. Irwin's account has been

described by the late British Ambassador and Burma specialist Peter Murray as "grossly overwritten

and factually unreliable; many of the adventures he claims to have had happened to other people."

No one in British Burma would dispute that there was a group of "Arakan Muslims" who could

indeed trace their roots back to the 17

th

Century and even earlier and who were quite distinct from

the Chittagonians and Bengali immigrants to Arakan. It might be that Irwin had seen some of their

villages. But there is nothing to confirm Irwin's broad assertion from any recognised British expert on

Burma, contemporary or modern-day, all of whom would profoundly disagree with his analysis.

I read that the Myanmar authorities are to make another attempt to include Rakhine Muslims in the

current census. I would not expect either side to give way on the issue of principle. It is however

suggested that a way out of the dilemma might be found by simply leaving the question on

'Ethnicity' blank. If the Muslims could agree to make this concession, which is in effect giving up the

right others have enjoyed to declare their ethnicity, that might resolve the problem for the present

and enable the vital statistics of this important group to be available for national planning services.

More especially, it would be a significant step towards recognition, notably in the issue of National

Registration Cards.

As British Ambassador Andrew Patrick admirably put it in a recent interview with Mizzima Business

Weekly: "Generally in the UK, and in Europe, ethnic groups are allowed to call themselves by the

name they want to use, whether or not that name has any historic validity. Of course when we use it,

thats not to say were expecting some sort of special status or a recognition of the Rohingya as an

ethnic group. That is for the Burmese parliament to decide. What I would say, is that its obviously

very important for that community to have the rights they are entitled to. And the Government has

made a commitment to ensure that everyone who is entitled to citizenship under the 1982 law gets

that."

I agree entirely. What more need I say?

Derek Tonkin

Editor - Network Myanmar

www.networkmyanmar.org

Heathfields, Berry Lane, Worplesdon, Guildford, Surrey GU3 3PU

Tel + 44 (0)1483 233576 - Mobile + 44 (0)7733 328832 - Email d.tonkin@btinternet.com

You might also like

- The Mujahid Rebellion in ArakanDocument3 pagesThe Mujahid Rebellion in ArakanDerek301229No ratings yet

- Who Are The Rohingyas-Dr. Aye ChanDocument6 pagesWho Are The Rohingyas-Dr. Aye ChanZwe Thit (Rammarmray)No ratings yet

- Rohingya Belong To Arakan and Then BurmaDocument7 pagesRohingya Belong To Arakan and Then Burmarohingyablogger86% (7)

- A Detailed Examination of Misinformation in DR Azeem Ibrahim's Book The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar's Hidden GenocideDocument15 pagesA Detailed Examination of Misinformation in DR Azeem Ibrahim's Book The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar's Hidden GenocideInformerNo ratings yet

- Oct 02 12 R'Gya - OriginDocument3 pagesOct 02 12 R'Gya - OriginAye Kyaw SoeNo ratings yet

- The Development of A Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar)Document25 pagesThe Development of A Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar)Khaing Khaing100% (1)

- Background of Rohingya ProblemDocument6 pagesBackground of Rohingya ProblemArakanbura100% (1)

- The Rohingyas:From Stateless To Refugee by Imtiaz Ahmed Professor of International RelationsUniversity of DhakaDocument13 pagesThe Rohingyas:From Stateless To Refugee by Imtiaz Ahmed Professor of International RelationsUniversity of Dhakacbro50No ratings yet

- 1947 Documents Are Revealing, and RelevantDocument12 pages1947 Documents Are Revealing, and RelevantRick HeizmanNo ratings yet

- 1947 Documents Are RevealingDocument12 pages1947 Documents Are RevealingRick HeizmanNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Francis BuchananDocument10 pagesAnalysis On Francis BuchananZwe Thit (Rammarmray)No ratings yet

- Historical Document of Rohingya-01Document9 pagesHistorical Document of Rohingya-01Mohammed Siddique BasuNo ratings yet

- Rohingya of Arakan by AFK JilaniDocument9 pagesRohingya of Arakan by AFK JilanimayunadiNo ratings yet

- Plight of Rohingyas HistoricityDocument3 pagesPlight of Rohingyas HistoricitymayunadiNo ratings yet

- Properties of Empire: Indians, Colonists, and Land Speculators on the New England FrontierFrom EverandProperties of Empire: Indians, Colonists, and Land Speculators on the New England FrontierNo ratings yet

- Arakan April Issue 2009Document16 pagesArakan April Issue 2009Arakan Rohingya National Org.No ratings yet

- Repatriation of Rohingya RefugeesDocument29 pagesRepatriation of Rohingya RefugeesmayunadiNo ratings yet

- Mag Arakan Dec09 StandardDocument16 pagesMag Arakan Dec09 StandardArakan Rohingya National Org.No ratings yet

- JUlY 2009Document16 pagesJUlY 2009rohingyabloggerNo ratings yet

- Citizens of a Stolen Land: A Ho-Chunk History of the Nineteenth-Century United StatesFrom EverandCitizens of a Stolen Land: A Ho-Chunk History of the Nineteenth-Century United StatesNo ratings yet

- The "Rohingyas", Who Are They?: The Origin of The Name "Rohingya"Document11 pagesThe "Rohingyas", Who Are They?: The Origin of The Name "Rohingya"Peaceful Arakan100% (3)

- 2018 Leider NameRohingya ASEANFocus Mar AprDocument3 pages2018 Leider NameRohingya ASEANFocus Mar AprChan MyaeNo ratings yet

- Magh Does Not Refer To Marma and RakhainDocument21 pagesMagh Does Not Refer To Marma and RakhainBodhi Mitra50% (2)

- Choanoac Indians Ethnic Transformation ADocument25 pagesChoanoac Indians Ethnic Transformation ADesmond Ellsworth100% (1)

- Sept 11 12 HISTORY and Etc.Document12 pagesSept 11 12 HISTORY and Etc.Aye Kyaw SoeNo ratings yet

- Irrefutable RohingyaDocument206 pagesIrrefutable RohingyaAnonymous 6UrHtpI2YNo ratings yet

- Two British Officers - 100 Years AgoDocument2 pagesTwo British Officers - 100 Years AgoRick HeizmanNo ratings yet

- The Muslim - Rohingyas of Burma by Martin Smith.Document17 pagesThe Muslim - Rohingyas of Burma by Martin Smith.Khin Maung MyintNo ratings yet

- Excellent Observations and Insight in 1949Document2 pagesExcellent Observations and Insight in 1949Rick HeizmanNo ratings yet

- Causes of The Rohingya ConflictDocument17 pagesCauses of The Rohingya ConflictNAMRAHNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Communalism in Contemporary Burma and Sri LankaDocument27 pagesThe Problem of Communalism in Contemporary Burma and Sri LankaM MengNo ratings yet

- Review of Moshe Yegar (1972), Muslims of BurmaDocument2 pagesReview of Moshe Yegar (1972), Muslims of Burmaarafat9194No ratings yet

- The Enslaved and Their Enslavers: Power, Resistance, and Culture in South Carolina, 1670–1825From EverandThe Enslaved and Their Enslavers: Power, Resistance, and Culture in South Carolina, 1670–1825No ratings yet

- The Westo Indians: Slave Traders of the Early Colonial SouthFrom EverandThe Westo Indians: Slave Traders of the Early Colonial SouthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- INSIGHT and OBSERVATIONS by R B SMARTDocument4 pagesINSIGHT and OBSERVATIONS by R B SMARTRick HeizmanNo ratings yet

- History, Issues and Truth in Arakan/Rakhine State, BurmaDocument19 pagesHistory, Issues and Truth in Arakan/Rakhine State, BurmaRick Heizman100% (2)

- A Short History of Rohingya and Kamas of BurmaDocument51 pagesA Short History of Rohingya and Kamas of BurmaKhin Maung MyintNo ratings yet

- Media UntruthfulDocument8 pagesMedia UntruthfulRick Heizman100% (1)

- African Americans in Long Beach and Southern California: a HistoryFrom EverandAfrican Americans in Long Beach and Southern California: a HistoryNo ratings yet

- In the True Blue's Wake: Slavery and Freedom among the Families of Smithfield PlantationFrom EverandIn the True Blue's Wake: Slavery and Freedom among the Families of Smithfield PlantationNo ratings yet

- Arakan September 2011 PDFDocument16 pagesArakan September 2011 PDFmayunadiNo ratings yet

- Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World, 1651-1825From EverandJewish Autonomy in a Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World, 1651-1825No ratings yet

- The Rohingya - The Ethnic People, Our History and PersecutionDocument98 pagesThe Rohingya - The Ethnic People, Our History and PersecutionFree Rohingya Coalition67% (3)

- Michael Charney's Public Talk On Rohingyas and Rakhines at Oxford Conference, May 2016Document5 pagesMichael Charney's Public Talk On Rohingyas and Rakhines at Oxford Conference, May 2016maungzarniNo ratings yet

- History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan: A Grammar of Their Language, and Personal and Family History of the AuthorFrom EverandHistory of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan: A Grammar of Their Language, and Personal and Family History of the AuthorNo ratings yet

- The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch StateFrom EverandThe Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch StateRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (6)

- Hidden Agenda of So-Called RohingyaDocument3 pagesHidden Agenda of So-Called RohingyaHan Maung100% (3)

- The Rohingya Crisis: Suu Kyi's False Flag and Eth-Nic Cleansing in ArakanDocument12 pagesThe Rohingya Crisis: Suu Kyi's False Flag and Eth-Nic Cleansing in Arakanvlad_ch93No ratings yet

- History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of MichiganFrom EverandHistory of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of MichiganRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDocument44 pagesThe Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDafner Siagian100% (1)

- Extract Indian Immigration Census 1911Document11 pagesExtract Indian Immigration Census 1911Derek301229No ratings yet

- The Rohingya IdentityDocument3 pagesThe Rohingya IdentityDerek301229No ratings yet

- Rohingya IdentityDocument11 pagesRohingya IdentityDerek301229No ratings yet

- MBF-No 27Document2 pagesMBF-No 27Derek301229No ratings yet

- Burmese Perspectives: Letter From GuildfordDocument4 pagesBurmese Perspectives: Letter From GuildfordDerek301229No ratings yet

- History Book Part I (A)Document32 pagesHistory Book Part I (A)Kovi DaNo ratings yet

- Torrential Monsoon Rains and Rising River Levels Have Caused FloodingDocument3 pagesTorrential Monsoon Rains and Rising River Levels Have Caused Floodingywon nay chi lwinNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Shalom Brochure PDFDocument35 pagesMyanmar Shalom Brochure PDFPann MyatNo ratings yet

- Nyaung Yan PeriodDocument9 pagesNyaung Yan Periodaungmyowin.aronNo ratings yet

- Rohingya History - Myth and RealityDocument76 pagesRohingya History - Myth and RealitymayunadiNo ratings yet

- Reports On The Antiquities of Arakan by DR Emil Forchhammer-1891 - 2Document115 pagesReports On The Antiquities of Arakan by DR Emil Forchhammer-1891 - 2Mohammed Sheikh Anwar100% (3)

- State Map District Rakhine MIMU764v04 23oct2017 A4Document1 pageState Map District Rakhine MIMU764v04 23oct2017 A4Anonymous triog0FPNo ratings yet

- Hudson-2014 Myanmar Burma ArchaeologDocument7 pagesHudson-2014 Myanmar Burma ArchaeologmyothawtunNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian Situation Report No. 10: HighlightsDocument5 pagesHumanitarian Situation Report No. 10: HighlightsSoe Thiha TinNo ratings yet

- WHKMLA - Timelines - History of ArakanDocument3 pagesWHKMLA - Timelines - History of ArakanmayunadiNo ratings yet

- Sacred Sites of BurmaDocument16 pagesSacred Sites of Burmayannaing nyeinNo ratings yet

- Using Magic Religion and Architecture ToDocument11 pagesUsing Magic Religion and Architecture ToKyaw MaungNo ratings yet

- The History of Maha Muni Image PDFDocument18 pagesThe History of Maha Muni Image PDFZwe Thit (Rammarmray)No ratings yet

- History Book Part I (B)Document24 pagesHistory Book Part I (B)Kovi DaNo ratings yet

- The Myth of A King A Princess and A Monk1Document9 pagesThe Myth of A King A Princess and A Monk1ေက်ာက္ၿဖဴသားေခ်No ratings yet