Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articulo Body and Social

Uploaded by

Angiee Ramirez MuñozOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Articulo Body and Social

Uploaded by

Angiee Ramirez MuñozCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 36: 335341, 2011

doi:10.1093/jmp/jhr027

Advance Access publication on September 2, 2011

The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press, on behalf of the Journal of Medicine and Philosophy Inc.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

Medicine as Combining Natural and

Human Science

HUBERT L. DREYFUS*

University of California, Berkeley, California, USA

*Address correspondence to: Hubert L. Dreyfus, Philosophy Department 2390, University of

California, Berkeley, CA 94720-2390, USA. E-mail: dreyfus@berkeley.edu

Medicine is unique in being a combination of natural science and

human science in which both are essential. Therefore, in order to

make sense of medical practice, we need to begin by drawing a

clear distinction between the natural and the human sciences. In

this paper, I try to bring the old distinction between the Geistes and

Naturwissenschaften up to date by defending the essential difference

between a realist explanatory theoretical study of nature including

the body in which the scientist discovers the causal properties of

natural kinds and the interpretive understanding of human

beings as embodied agents which, as Charles Taylor has convinc-

ingly argued, requires a hermeneutic account of self-interpreting

human practices.

Keywords: Charles Taylor, human sciences, medicine, natural

sciences

I. INTRODUCTION

Medicine is unique in being a combination of natural science and human

science in which both are essential. Therefore, in order to make sense of

medical practice we need to begin by drawing a clear distinction between

the natural and the human sciences. In my talk, I will try to bring the old

distinction between the Geistes and Naturwissenschaften up to date by

defending the essential difference between a realist explanatory theoretical

study of nature including the human body in which the scientists discovers

the causal properties of natural kinds and the interpretive understanding of

human beings as embodied agents which, as Charles Taylor has convinc-

ingly argued, requires a hermeneutic account of our self-interpreting human

practices.

Hubert L. Dreyfus 336

II. HOW NATURAL SCIENCE CAN DISCOVER TRUTHS ABOUT NATURE

AS IT IS IN ITSELF

Before spelling out Taylors view, I need to dene what I mean by scientic

theory. Theorizing is a special form of intellectual activity discovered by

Socrates and rened by the philosophical tradition. It has six essential char-

acteristics, never fully achieved, but approached to varying degrees. (The rst

three are introduced by Socrates).

(1) Explicitness. A theory should not be based on intuition and

interpretation but should be spelled out so completely that it can be

understood by any rational being.

(2) Universality. Theory should hold true for all places and all times.

(3) Abstractedness. A theory must not require reference to particular

examples.

Descartes and Kant support the Socratic account of theory by adding

three further requirements:

(4) Discreteness. A theory must be stated in terms of context-free

elementselements that make no reference to human interests,

traditions, institutions, etc.

(5) Systematicity. A theory must be a whole in which decontextualized

elements (properties, attributes, features, factors, etc.) are related to

each other by rules or laws.

1

(6) Closure and prediction. The description of the domain investigated

must be complete, that is, it must specify all the inuences that affect

the elements in the domain and must specify their effects. Closure

permits precise prediction.

Many recent philosophers of science hold that science cannot even approach

the ideal of theory. They contend that scientic entities are social construc-

tions essentially related to human purposes. Such thinkers conclude from the

fact that background practices are necessary for access to theoretical entities

that these entities must be dened in terms of these access practices.

Martin Heidegger opposes this view in Being and Time. Heidegger argues

that only human beings make sense of things. So the ontological intelligibility

of the mode of being of each kind of thing, including natural things,

depends upon our practices. Still nature as a being, or as an ensemble of

beings, need not depend on us. This is one way we make sense of things as

occurrent (vorhanden), that is, as natural kinds whose ontic intelligibility is

only contingently related to our access practices.

Occurrent beings are revealed when we take a detached attitude towards

things and decontextualize them. Then things show up as independent of

human purposes and even as independent of human existence. Decontextu-

alizing takes place in two stages. First we use skills and instruments to isolate

Medicine as Combining Natural and Human Science 337

things and their properties which then appear as meaningless objects, colors,

shapes, sounds, etc. Such data are independent of our purposes but still

dependent upon our senses.

We then complete this deworlding by inventing theories in which the

occurrent data are taken up as evidence for quasars and quarks and other

entities we cannot directly experience. These theoretical entities need not

conform at all to our sense experience nor to our everyday understanding of

objects, space, time, and causality. According to our current successful un-

derstanding of nature, such entities belong to natural kindstypes of things

like water, gold, iron, etc.and if correct, our natural science describes the

causal powers of these natural kinds. There is no way to stand outside cur-

rent science and give it metaphysical support by arguing that there must be

natural kinds or that these are what our science must be about. All that

philosophy can do is show that the natural scientists background assump-

tion that there is some way nature is in itself is not incoherent.

If we encountered things only in using them, never in detachedly reect-

ing on them, that is, if availableness (Zuhandenheit) were the only way of

being we knew, we would not be able to make the notion of entities in

themselves intelligible. But since we understand occurrentness, we under-

stand that occurrent entities can have existed even if human beings had

never existed. Indeed, given our understanding of occurrentness, we must

understand things this way. To take a Heideggerian example, what it is to be

a hammer essentially depends upon Dasein and its cultural artifacts. It be-

longs to the being of a hammer that it is used to pound in nails for building

houses, etc. In a culture that always tied things together, there could be no

hammers. But there could, nonetheless, be pieces of wood with iron blobs

on the end since wood and iron are natural kinds and their being and causal

powers make no essential reference to human purposes.

But even if physical science is progressing in its understanding of physical

nature, a theory of the causal powers of natural kinds tells us only what is

causally real, so modern science need not be the only way of understanding

nature. As Heidegger, rightly, sees, many different practices can reveal nature

as it is in itself.

What is represented by physics is indeed nature itself, but undeniably it is only

nature as the object-area, whose objectness is rst dened and determined through

the rening that is characteristic of physics .... Nature, in its objectness for modern

physical science, is only one way in which what presenceswhich from of old has

been named physisreveals itself. (Heidegger, 1977, 17374)

This leaves open the possibility that acupuncture, for example, taps into

some sort of energy and causality unknown in our Western medicine.

It follows from the above considerations that what counts as real for a

culture depends upon the interpretation in its practices, but this does not

make what is thus revealed any less real. We could call this position plural

Hubert L. Dreyfus 338

realism. For a plural realist, there is no point of view from which one can

ask and answer the metaphysical question concerning the one true nature of

ultimate reality. Given the dependence of the intelligibility of all ways of

being on our practices, and the dependence of what counts as elements

of reality on our purposes, the question makes no sense. But since differ-

ent practices reveal different realities or domains of intelligibility, and since

no one way of revealing is exclusively true, accepting one does not commit

us to rejecting the others. We can hold that our natural science can be getting

it righter and righter about how things work, even if there can be no one

right account of how things are.

III. WHY CURRENT HUMAN SCIENCES MUST BE HERMENEUTIC?

The phenomenon that leads one to expect a basic difference between the

natural sciences and the disciplines that study human beings is clear. The

natural sciences may not be as rational nor as cumulative as once believed,

but they still show stability and progress. For extended periods, sciences like

physics exhibit an agreed upon way of doing research. Occasionally dis-

agreement arises as to how to account for anomalies. This can develop into

a crisis that continues until the anomalies are removed by some new scheme

that gains agreement, establishing a new normal science. But even when

previously accepted theories are abandoned, many results are conserved.

The human sciences, on the other hand, have been neither stable nor

cumulative. These dubious disciplines, to use Foucaults pejorative phrase,

do not progress through revolutions like physical science but merely go

through episodes in which certain fads tend to dominate research until some

competing fad lures most researchers onto its bandwagon. One style of re-

search gives way to another not because the new research is based upon a

theory which explains certain anomalies the old theory failed to explain but

simply because researchers have become bored and discouraged with the

old approach. The new style, introducing new methods and problems, al-

lows everyone to forget the old problems. Thus, the human sciences are

subject to frequent factionalism and reorganization, but this is not a crisisa

period of competing paradigms. It is a pre-paradigm state. The human sciences

are not even generally stable nor are they even occasionally cumulative.

But disagreement arises as soon as one tries to interpret the above con-

trast. For example, Richard Rorty holds that although at present the human

sciences are unable to nd an agreed upon vocabulary, this fact has nothing

to do with the essential nature of man or of science. It is simply an effect of

the complexity of the domain and the immaturity of the human sciences.

But this way of dismissing the difference is too simple. The argument that

the human sciences are young is beginning to show its age. Looked at his-

torically the social sciences make a quite different impression than sciences

Medicine as Combining Natural and Human Science 339

such as genetics or climatology that are struggling with a very complex

domain. These latter sciences are making slow but steady progress in devel-

oping more and more complicated theories that take into account more and

more factors, whereas the human sciences rst seek to develop a general

theory using one approach, then scrap that attempt in toto, and take up

some other equally simplistic general research program.

To take a recent example, the behaviorists sought a complete description

of human action in terms of elements of behavior and covering laws that

predicted the occurrence of particular behavioral events. When this approach

came up against hard problems such as linguistic behavior, it was quickly

abandoned and cognitivism became popular. Cognitivists rejected all the

behaviorists carefully compiled results as artifacts and sought to explain

human behavior by analyzing the rule-like relations holding between mental

representations. Both approaches aim, in the ideal limit, at attaining the sort

of complete explanatory account which allows one to predict precisely the

effects of alterations in an objects internal and external environment, and

each fails to achieve its goal. It looks more and more like there must be

something about human activity, on the one hand, and the nature of theo-

retical explanation, on the other, which do not t together.

Why does the sort of theoretical explanation that succeeds brilliantly in

the natural sciences fails in the human sciences? The problem Taylor holds

lies in the attempt to apply theory to the everyday world. Just as physical

science predicts and explains everyday changes of place in terms of mean-

ingless, context-independent properties such as mass and position that can

be abstracted from the everyday world, so a theoretical science of human

beings seeks to abstract meaningless, context-free features from every-

day, context-dependent, meaningful human activities, and then predict and

explain these everyday activities in terms of formal relations between these

elements. Insofar as these would-be sciences follow the ideal of physical

theory, they must predict and explain everyday activities, using decontextu-

alized features. But since the context in which human beings pick out the

everyday objects and events whose regularities theory attempts to predict is

left out in the decontextualization necessary for theory, the everyday objects,

and events human beings pick out do not always coincide with those entities

over which the theory ranges. Therefore, predictions, though often correct,

are not reliable. Indeed, predictions will work only as long as the elements

picked out and related by the theory happen to coincide with the objects and

events picked out by human beings in their everyday activities.

A striking example of what happens when one tries to study human

beings as objects was given inadvertently by a Stanford psychologist who

announced that his science had discovered that although people classify

some people as talkative and others as taciturn, and although there is gen-

eral agreement among participants in the everyday world as to which people

belong in which class, the concept of talkativeness is unfounded. If you

Hubert L. Dreyfus 340

count the number of words uttered by an individual in a day, the would-be

theorist explained, you nd that there is no signicant difference in the

quantity of words uttered by so-called taciturn and by so-called talkative

people.

It never occurred to this objective psychologist that what makes a person

count as talkative may be the meaning of what is said and the situation in

which it is said. Talkative people presumably say little of importance and say

it during other peoples lectures, at funerals, etc. The general agreement

among participants in the everyday world as to who is talkative is presum-

ably no illusion. Rather the sort of data collection appropriate to the natural

sciences, where one studies objects and counts words, is simply inappropri-

ate to the study of human beings understanding of themselves and other

human beings. People making judgments such as who is talkative agree be-

cause they dwell in a shared background of meaningful practices. In general,

in the human sciences, if one is to understand what is going on, one must

share a general human background understanding with the person or group

being studied. Shared agreement disappears as soon as the meaning of the

situation is excluded in the attempt to attain the sort of objectivity appropriate

to natural science.

This thesis can be further illustrated by the sort of difculties that, according

to Pierre Bourdieu, confront Lvi-Strausss structuralist theory of gift exchange.

In Outline of a Theory of Practice, Bourdieu argues that Lvi-Strausss formal,

reversible rules for the exchange of giftsabstracted as they are from every-

day gift-givingcannot account for and predict actual exchanges. His point

is not that theory leaves out the subjective, so-called phenomenological,

qualities of gift exchange. That would not be a valid objection. The natural

sciences legitimately abstract from subject-relative properties. Bourdieus

point is that Lvi-Strausss abstraction of the pure objects exchanged leaves

out something essential. The tempo of the event actually determines what

counts as a gift. Bourdieu notes:

In every society it may be observed that, if it is not to constitute an insult, the counter-

gift must be deferred and different, because the immediate return of an exactly identical

object clearly amounts to a refusal. (Bourdieu, 1977, 5, my italics)

Predictions based only on formal principles fail in those cases in which what

formally counts as a gift in the theory is rejected in everyday practice be-

cause it is reciprocated too soon or too late to count as a gift. According to

Bourdieu

It is all a question of style, which means in this case timing and choice of occasion, for

the same actgiving, giving in return, offering ones services, paying a visit, etc.can

have completely different meanings at different times (Bourdieu, 1977, 6).

In general the meaning of the situation plays an essential role in determining

what counts as an object or event that is it constitutes the event. It does not

Medicine as Combining Natural and Human Science 341

just give us access to it as in natural science. Yet it is precisely this back-

ground meaning that theory must ignore. Thus, imprecision in the human

sciences is inevitable because what counts as an everyday fact depends on

a background of meanings and skills that is excluded by the decontextual-

ization required by theory. Predictive failure is a constant possibility in any

area where facts such as being talkative or being a gift depend on back-

ground practices not integrated into the theory. Prediction will fail whenever

an object that according to the theory has the dening features of a given

type is nonetheless not counted by those in the culture.

I have tried to elaborate Charles Taylors arguments for a hermeneutic

distinction between the natural and social sciences. It must be taken into

account if one wants to understand the peculiar status of medicine as both

a human and natural science.

NOTES

1. In asserting that theories range over decontextualized, uninterpreted facts, I am not endorsing a

positivist account of theories as based on brute data. The basic data are meter reading and computer

printouts. These uninterpreted facts are cut off from our everyday world of equipment and purposes

but they are, of course, recontextualized or theory laden, otherwise they could not ll in variables asking

for mass, charge, etc.

REFERENCES

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Heidegger, M. 1977. Science and reection. In The question concerning technology and other

related essays (pp. 15582), trans. W. Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row.

Copyright of Journal of Medicine & Philosophy is the property of Oxford University Press / UK and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Philosophy of Evolution Together With a Preliminary Essay on The Metaphysical Basis of ScienceFrom EverandThe Philosophy of Evolution Together With a Preliminary Essay on The Metaphysical Basis of ScienceNo ratings yet

- Consciousness and Cosmos: Proposal for a New Paradigm Based on Physics and InrospectionFrom EverandConsciousness and Cosmos: Proposal for a New Paradigm Based on Physics and InrospectionNo ratings yet

- The Hermetic Science of Transformation: The Initiatic Path of Natural and Divine MagicFrom EverandThe Hermetic Science of Transformation: The Initiatic Path of Natural and Divine MagicRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The Law of Psychic Phenomena: A Systematic Study of Hypnotism, Spiritism, Mental TherapeuticsFrom EverandThe Law of Psychic Phenomena: A Systematic Study of Hypnotism, Spiritism, Mental TherapeuticsNo ratings yet

- Meet Your Sexual Mind: The Interaction Betwen Instinct and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorFrom EverandMeet Your Sexual Mind: The Interaction Betwen Instinct and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Volume 10. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Fundamental Principles of Immortality»From EverandVolume 10. Immortality is accessible to everyone. «Fundamental Principles of Immortality»No ratings yet

- THE INSTINCT OF WORKMANSHIP & THE STATE OF THE INDUSTRIAL ARTSFrom EverandTHE INSTINCT OF WORKMANSHIP & THE STATE OF THE INDUSTRIAL ARTSNo ratings yet

- Science and Supernatural IsmDocument15 pagesScience and Supernatural IsmV.K. MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Forrest PhiloDocument23 pagesForrest PhiloAaron AppletonNo ratings yet

- Contact with the Other World - The Latest Evidence as to Communication with the DeadFrom EverandContact with the Other World - The Latest Evidence as to Communication with the DeadNo ratings yet

- The Law of Psychic Phenomena: A working hypothesis for the systematic study of hypnotism, spiritism, mental therapeutics, etcFrom EverandThe Law of Psychic Phenomena: A working hypothesis for the systematic study of hypnotism, spiritism, mental therapeutics, etcNo ratings yet

- The Story of the Living Machine: A Review of the Conclusions of Modern Biology in Regard / to the Mechanism Which Controls the Phenomena of Living / ActivityFrom EverandThe Story of the Living Machine: A Review of the Conclusions of Modern Biology in Regard / to the Mechanism Which Controls the Phenomena of Living / ActivityNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Big Picture: by Sean Carroll | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of The Big Picture: by Sean Carroll | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Big Picture: by Sean Carroll | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of The Big Picture: by Sean Carroll | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Christianity as Mystical Fact, and the Mysteries of AntiquityFrom EverandChristianity as Mystical Fact, and the Mysteries of AntiquityNo ratings yet

- Vol. May, NO.: Science and The Origin of Life: H. T. EdgeDocument69 pagesVol. May, NO.: Science and The Origin of Life: H. T. EdgeOcultura BRNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Occult Healing - A Working Hypothesis Which Includes All Cures - Studies by a Group of Theosophical StudentsFrom EverandThe Principles of Occult Healing - A Working Hypothesis Which Includes All Cures - Studies by a Group of Theosophical StudentsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of ScienceDocument8 pages6 - Sri Aurobindo's Perspective On The Future of ScienceK.S. Bouthillette von OstrowskiNo ratings yet

- Quantum Physics and Ultimate Reality: Mystical Writings of Great PhysicistsFrom EverandQuantum Physics and Ultimate Reality: Mystical Writings of Great PhysicistsNo ratings yet

- Crane Mellor No QuestionDocument23 pagesCrane Mellor No QuestionLuca BarlassinaNo ratings yet

- Materialist OntologyDocument16 pagesMaterialist OntologyJuan Jesús RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Methods and Problems in The History of Ancient ScienceDocument14 pagesMethods and Problems in The History of Ancient Scienceravi bungaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document22 pagesChapter 2Pauline AñesNo ratings yet

- Husserl - Vienna LectureDocument27 pagesHusserl - Vienna LecturePhilip Reynor Jr.No ratings yet

- The Natural vs. The Human Sciences:: Myth, Methodology and OntologyDocument18 pagesThe Natural vs. The Human Sciences:: Myth, Methodology and OntologySvea ShahNo ratings yet

- Science and Scientific MethodDocument10 pagesScience and Scientific MethodXia Allia100% (1)

- Science and Religion - Compatible or in Conflict - Iasn Berbour Fourfold TypologyDocument9 pagesScience and Religion - Compatible or in Conflict - Iasn Berbour Fourfold TypologyGodswill M. O. UfereNo ratings yet

- WISDocument10 pagesWISmarcgpNo ratings yet

- 10.1016@0016 32877490046 9Document21 pages10.1016@0016 32877490046 9rosehakko515No ratings yet

- AGAINST METHOD Feyerabend SazetakDocument15 pagesAGAINST METHOD Feyerabend SazetakHistorica VariaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - The Nature and Practice of ScienceDocument13 pagesModule 1 - The Nature and Practice of ScienceTOBI JASPER WANGNo ratings yet

- Overview of ScienceDocument3 pagesOverview of ScienceJoseph Ndung'uNo ratings yet

- Human Person and The SocietyDocument37 pagesHuman Person and The SocietyEuvher Villadolid0% (1)

- Christopher Norris Truth Matters 2002Document237 pagesChristopher Norris Truth Matters 2002Deznan BogdanNo ratings yet

- Aristotelian Vs StoicismDocument6 pagesAristotelian Vs StoicismJana GhandourNo ratings yet

- Fullerton Intro To Philosophy - Fall 2019 - Tuesday-330Document6 pagesFullerton Intro To Philosophy - Fall 2019 - Tuesday-330廖承钰No ratings yet

- Machiavelli ReportDocument2 pagesMachiavelli Reportjm_omega23No ratings yet

- Anthony GiddensDocument12 pagesAnthony Giddensburnnotetest0% (1)

- Human Composition of Man: TopicDocument35 pagesHuman Composition of Man: TopicIzaak CabigonNo ratings yet

- What Is Civil Society Organization?Document6 pagesWhat Is Civil Society Organization?GENALYN CHANNo ratings yet

- Hayden White A Portrait in Seven Poses IDocument23 pagesHayden White A Portrait in Seven Poses Ipopmarko43No ratings yet

- UtsDocument4 pagesUtsArchie Villaluz100% (1)

- E.V. Ilyenkov - Dialectic Logic - Essays On Its History and Theory-Progress Publishers (1977)Document121 pagesE.V. Ilyenkov - Dialectic Logic - Essays On Its History and Theory-Progress Publishers (1977)Rodrigo Duarte BaptistaNo ratings yet

- Never Attribute To Malice That Which Is Adequately Explained by StupidityDocument1 pageNever Attribute To Malice That Which Is Adequately Explained by StupidityJames HanlonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - World ReligionDocument35 pagesLesson 2 - World ReligionFredinel Malsi ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Performance Task: Me and The Philosopher's View of The SelfDocument3 pagesPerformance Task: Me and The Philosopher's View of The SelfPauNo ratings yet

- Philosophies of Education: Philosophical Positions and Statements of PurposeDocument47 pagesPhilosophies of Education: Philosophical Positions and Statements of PurposeJoe Mar BernabeNo ratings yet

- Poststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)Document4 pagesPoststructuralism (Derrida and Foucault)ROUSHAN SINGHNo ratings yet

- Assemblage Theory, Complexity and Contentious Politics: The Political Ontology of Gilles Deleuze by Nick SrnicekDocument130 pagesAssemblage Theory, Complexity and Contentious Politics: The Political Ontology of Gilles Deleuze by Nick SrnicekJohannes TinctorisNo ratings yet

- Angelic Sin - Augustin Original Sin PDFDocument47 pagesAngelic Sin - Augustin Original Sin PDFNovi Testamenti FiliusNo ratings yet

- Rawls's Justice As FairnessDocument7 pagesRawls's Justice As FairnessDuván Duque VargasNo ratings yet

- DerridaDocument16 pagesDerridaBill ChenNo ratings yet

- Green Politics EcologismDocument2 pagesGreen Politics EcologismGWEZZA LOU MONTONNo ratings yet

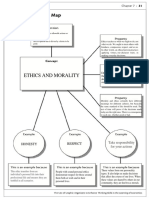

- Ethics and Morality: Honesty RespectDocument1 pageEthics and Morality: Honesty RespectMarc ViduyaNo ratings yet

- NColge 1373 Western PhilosophyDocument303 pagesNColge 1373 Western PhilosophyVasaviNo ratings yet

- Q3 M5 PhilosophyDocument2 pagesQ3 M5 PhilosophyDonna Lyn Domdom PadriqueNo ratings yet

- TRM 409.01 Slavery in The Chocolate IndustryDocument3 pagesTRM 409.01 Slavery in The Chocolate IndustryNeşe Roman0% (1)

- TOK Essay ChecklistDocument1 pageTOK Essay Checklistanon_976339735No ratings yet

- FRY, Tony - The Origin of The Work of DesignDocument13 pagesFRY, Tony - The Origin of The Work of DesignMario Victor MargottoNo ratings yet

- C. Discussion: Who Am I? 1. Socrates, Plato, AugustineDocument6 pagesC. Discussion: Who Am I? 1. Socrates, Plato, AugustineLuzviminda Lacno VillarNo ratings yet

- Johnson - Derrida and ScienceDocument18 pagesJohnson - Derrida and ScienceMaureen RussellNo ratings yet

- Theology NotesDocument3 pagesTheology NotesNia De GuzmanNo ratings yet

![A Critical History of Greek Philosophy [Halls of Wisdom]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/375417549/149x198/74c190f35a/1668643896?v=1)