Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bridger - Some Fundamental Aspects of Posture Related To Ergonomics

Uploaded by

Eduardo DiestraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bridger - Some Fundamental Aspects of Posture Related To Ergonomics

Uploaded by

Eduardo DiestraCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 8 (1991 ) 3-15 3

Elsevier

Some fundamental aspects of posture related to ergonomics

R.S. Bridger

UCT Medical School and Groote Schuur Hospital, Observatory 7925, Cape Town, South Africa

(Received September 10, 1990; accepted in revised form December 21, 1990)

Abs t r a c t

This paper presents a broad review of some fundamental aspects of posture in terms of structure, function and control (including

dysfunction and postural behaviour) and attempts to derive implications for ergonomics. It begins by reviewing research on the

anatomical basis of the upright bipedal posture in man and its evolutionary development, based on recent fossil discoveries.

Relevant aspects of the anatomy of the spine, pelvis and hip are then reviewed together with some developmental aspects of

posture and a consideration of postural faults and muscle balance gleaned from the clinical fiterature. Further clinical aspects are

discussed to introduce the concepts of postural control, feedback and postural behaviour. Finally, some aspects of cross-cultural

postural variation are briefly reviewed.

It is concluded that empirical research on posture and effective workspace design can benefit from a consideration of these

fundamental aspects of posture. Much of modern design practice would appear to be built around a limited set of postural

stereotypes which are probably culturally biased and do not reflect the true limitations and possibilities of human anatomy. Whether

improved designs can be implemented on the basis of these fundamentals is both an empirical question and a challenge to the

ingenuity of designers.

Re l e v a n c e t o i ndus t ry

Postural stress and occupationally-related musculoskeletal disorders have a high incidence in the industrially developed nations of

the world. Much research is currently underway to determine the reasons for this and provide designers with more effective

guidelines. This paper presents a review of fundamental aspects of posture to provide a wider conceptual basis for the investigation of

these problems.

Ke y wo r d s

Posture, hip, pelvis, spine, hominids, bipedalism.

I nt r o duc t i o n

Cu r r e n t r e s e a r c h o n wo r k i n g p o s t u r e a n d i t s

r e l a t i o n t o h e a l t h a n d i n d u s t r i a l e f f i c i e n c y i s r e -

v i e we d i n n u me r o u s r e c e n t p u b l i c a t i o n s ( see, f o r

e x a mp l e , Co r l e t t et al . , 1986; Gr i e c o , 1986;

Ki l b o m, 1988) . A k e y i n t e r e s t i s t h e me a s u r e me n t

o f s t r a i n i n mu s c l e s a n d j o i n t s i n r e s p o n s e t o

p o s t u r a l s t r e s s e s i mp o s e d b y t h e d e s i g n o f a

wo r k s p a c e o r t as k. Th i s e n a b l e s d e s i g n a l t e r n a -

t i ve s t o b e e v a l u a t e d o n t h e b a s i s o f q u a n t i t a t i v e

d a t a c o n c e r n i n g p o s t u r a l s t r e s s o r s t r a i n a n d p r o -

v i d e s a r a t i o n a l , i f s o me t i me s e mp i r i c a l , b a s i s f o r

d e s i g n g u i d e l i n e s .

I t i s n o t t h e p u r p o s e o f t hi s p a p e r t o r e v i e w t hi s

r e s e a r c h , s i n c e t hi s h a s b e e n d o n e e l s e wh e r e ( s ee

Co r l e t t e t al . , 1986; Gr i e c o , 1986; Na c h e ms o n ,

1976; Ag h a z a d e h et al . , 1989, f o r e x a mp l e ) . He r e ,

s o me f u n d a me n t a l a s p e c t s wi l l b e r e v i e we d wi t h

t h e e mp h a s i s o n g r o s s a n a t o my a n d wh o l e b o d y

0169-1936/91/$03.50 1991 - Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture

post ure, its devel opment , cont r ol and cross-cult-

ural mani fest at i ons. Some i mpl i cat i ons for ergo-

nomi cs will t hen be identified.

T h e upri ght pos t ure: I t s or i gi ns , ant i qui t y and

a n a t o my

The upri ght post ur e and bi pedal mode of

l ocomot i on t hat characterises Homo sapiens has a

long evol ut i onary history. Chart eri s et al. (1982)

at t empt ed to reconst ruct the gait of Aust ral o-

pi t hecus afarensis f r om 3.7 million year old fossil-

ized foot pri nt s f ound at Laetoli, East Africa. Thei r

estimates of stride length, cadence and velocity led

t hem to concl ude t hat Aust ral i pi t hecus was fully

bipedal. Jungers (1982), however, quest i oned

whet her the aust ral opi t heci ne adapt at i on t o bi-

pedal i sm was fully mode m on the basis of an

analysis of limb lengths.

Research on physical ant hr opol ogy in general

and homi ni d evol ut i on in part i cul ar is of interest

since compar at i ve analysis of t he anat omy of earl y

homi ni ds, Homo sapiens and moder n great apes

can help specify the adapt at i ons requi red for the

adopt i on and mai nt enance of t he upri ght post ur e

and, indeed, clarify what is meant by the t er m

post ure as it is used in Ergonomics.

Fi gure 1 depicts t he bi pedal post ure adopt ed by

a human and by a chi mpanzee. In the chi mpanzee,

the cent er of gravi t y (C. O. G. ) of the body lies

ant er i or to the l umbar spine and hip. In the hu-

man, it lies above the hip j oi nt . Thi s reduces the

mechani cal di sadvant age of the gluteal muscles in

keepi ng the t r unk erect. Not e also t hat t he chim-

panzee has limited hi p ext ensi on and cannot ex-

t end the hip to place the femur per pendi cul ar to

the ground. Thi s is due to length and posi t i on of

the ischium. In evol ut i onary terms, the mai n

anat omi cal adapt at i ons t o bi pedal i sm can be sum-

mari sed as follows (see Robi nson, 1972; Zi hl man

and Brunker, 1973; McHenr y and Temeri n, 1979;

Tobi as, 1982; and, for mor e popul ar t reat ment s of

the subject, Napi er, 1967 and Lovej oy, 1988):

- A lowering of the relative C. O. G. of the body

by means of a br oadeni ng and fl at t eni ng of the

ilium and sacrum as well as a short eni ng of the

arms and a l engt heni ng of the legs.

- A change in t he funct i on of t he gluteal muscles

(figure 2). In apes, gluteus medi us and gluteus

. ~ C.O.G.

Fig. 1. The bi pedal pos t ur e i n ma n a n d c hi mpa nz e e - not e t he

l ocat i on of t he cent er of gr avi t y ( C. O. G. ) of t he b o d y i n

rel at i on t o t he hi p j oi nt ( Ada pt e d f r om Zi h l ma n a nd Br unker ,

1979).

mi ni mus are maj or hi p ext ensors used for

l ocomot i on while gluteus maxi mus is of mi nor

i mport ance. These muscles are at t ached to t he

iliac bl ades and t he upper femur. In chi mpan-

zees, the iliac bl ades are flat and lie across the

back of t he t orso in a single pl ane (figure 2b),

whereas in homi ni ds (i ncl udi ng Homo Sapiens),

the ilium is r ot at ed forwards ar ound t he body

(figure 2c). This displaces t he ant er i or gluteals

i nt o a lateral posi t i on on t he body and convert s

t hem to hi p abduct ors. Gl ut eus maxi mus re-

mai ns post eri orl y posi t i oned but exhibits hyper -

t rophy. In homi ni ds, its f unct i on is no l onger

l ocomot i on but t o stabilise t he t r unk and pre-

vent it ' j ackkni fi ng' forwards over the legs when

walking. The sacrum widens to leave r oom f or

the viscera and bi rt h canal.

For par t of t he bi pedal gait cycle, t he pelvis is

onl y suppor t ed on one leg. To stabilise the

upper body, t he r eor i ent at ed ant er i or gluteals

act as hi p abduct ors. Viewed front al l y, it can be

seen t hat the hip j oi nt acts as a ful crum with

t he weight of t he body and t he unsuppor t ed leg

exerting a moment on one side which is coun-

t eract ed by the abduct or s on the ot her (figures

Anterior

Gluteals

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture

Sacrum

Ilium

( a )

( c )

Ilium

( d )

Fig. 2. The hi p and pel vi s rel at ed t o post ure. (a) Fr ont al view of a huma n pelvis and hi p j oi nt . The j oi nt act s as a f ul cr um dur i ng

wal ki ng. The ant er i or gluteals, act i ng as hi p abduct or s, count er act t he mome nt exer t ed by t he upper t or so and uns uppor t ed leg. (b)

Top view of t he pel vi s of a chi mpanzee. Not e t hat t he iliac bl ades lie al most flat, in a single pl ane. The gl ut eal muscl es act as hi p

ext ensor s in t he chi mpanzee. (c) Top view of a human pelvis. Not e t he curved ilia whi ch pr ovi de l at eral at t achment poi nt s f or t he

ant er i or gluteals, enabl i ng t hem to abduct t he hip. (d) ' Tr endel enbur g' post ur e. Weakness of t he f i ght ant er i or gl ut eal s causes

devi at i on of t he pel vi s t o t he ri ght and lateral t i l t i ng t o t he left. The spi ne exhi bi t s compens at or y scoliosis. Thi s t ype of pos t ur e can

al so be obser ved when peopl e st and on an uneven surface to work. ( Adapt ed f r om Lovej oy, 1988, and Kendal l et al., 1971.)

2a and 2d). In homi ni ds, t he femoral neck is

l engt hened and the ilium is fl ared out ward,

away f r om t he body to increase t he lever arm of

the hip abduct ors. Peopl e wi t h weak or para-

lysed hip abduct or s exhi bi t t he ' Tr endel enbur g'

gait in which the pelvis tilts t owards the unsup-

por t ed leg and the upper body bends t owards

t he suppor t ed leg (figure 2d).

- T h e ilium expands post eri orl y, bri ngi ng the

C. O. G. of t he body closer to the hi p j oi nt in the

sagittal plane.

- In or der to st and erect, the spine must be

reposi t i oned f r om hori zont al in t he quadr upedal

post ur e t o vertical in bi pedal post ure. Thi s can-

not be achieved by simply rot at i ng t he pelvis on

the vertical f emur by 90 degrees until the t r unk

is erect, because the ext ensi on of t he f emor a

requi red for walking (i.e. ext ensi on past t he

vertical by the trailing leg) is t hen i mpeded by

the ischium (figure 3). Thi s is one reason why

t he great apes cannot walk on two legs effi-

ci ent l y (figure 3b). Furt her, t he sacrum cannot

be r ot at ed backwards with respect t o the ilium.

Al t hough this woul d hel p to pl ace t he spi ne in a

vertical posi t i on, while using less t han 90 de-

grees of hi p extension, t he bi rt h canal woul d

t hen be obst r uct ed by t he coccyx. Somewhat

count eri nt ui t i vel y, t he evol ut i onar y sol ut i on

seems to have been t o r ot at e t he sacrum for-

wards on the i schi um and i ncrease t he ext en-

sion of t he l umbar spine. Thi s is t he origin of

t he l umbar lordosis whi ch is of so much con-

cern to researchers in seating. Accor di ng t o

Far f an (1978), t he post er i or l umbar (supra-

spinous) l i gament s and t he zygapophyseal j oi nt s

of the f our t h and fi ft h l umbar ver t ebr ae are

specially adapt ed in man t o resist t he l umbo-

sacral shear force whi ch is br ought about by t he

tilt of the sacrum and whi ch is exacer bat ed

when obj ect s are lifted.

The pelvis can be seen as t he base on whi ch t he

spi ne is support ed. Ma ny muscl e groups which,

in ot her species, pr ovi de l ocomot i ve power take

on new roles in t he bi pedal post ure. As de-

scribed above, t he ant er i or gluteals now stabil-

ise the pelvis. The iliopsoas muscl es i ni t i at e

' swi ng-t hrough' of the trailing leg in wal ki ng

and the hamst ri ngs decel erat e it pr i or t o heel

strike. Onl y t he quadri ceps and t he pl ant arfl ex-

ors (gast rocnemi us and soleus muscles) are left

t o pr ovi de a gr ound r eact i on force f or l ocomo-

t i on in walking.

6 R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture

(a) (b) (c)

Fig. 3. Ori ent at i on of the ischium with respect to the hip joint.

(a) Man standing erect. (b) Chimpanzee standing erect. (c)

Chimpanzee in normal quadrupedal posture. In (b), the ischium

prevents extension of the thigh past the vertical. Comparison

of (a) and (c) reveals the fundamental nat ure of the l umbar

lordosis as an adapt at i on to erect bipedalism. (Adapt ed from

Robinson, 1972.)

- Alterations in foot morphology.

- A decrease in hip and knee j oi nt mobility.

The fossil record provides considerable insights

i nt o the evolution of the upright posture over time

and the anat omi cal adapt at i ons which bipedalism

requires (interestingly, as Kapandj i , 1970, points

out, the true physiological position of the hip in

man corresponds to the position on all fours. In

standing, the head of the femur coincides imper-

fectly with the acetabular cavity. This is used to

argue in favour of man' s evolution from quadruped

ancestors). According to Far f an (1978), the l umbar

lordosis and other adapt at i ons provide an over-

abundance of power for at t ai ni ng the upright pos-

ture. The erection of the t runk has been achieved

onl y part l y by the backward rot at i on of the pelvis,

the rest by the inversion of the normal quadrapedal

l umbar curve (concave anteriorly) i nt o a l umbar

lordosis (concave posteriorly).

T h e hip and pelvis: S o me a n a t o mi c a l a s p e c t s re-

lated t o p o s t u r e

In erect standing, as has been described, onl y

part of the erection of the t runk is accomplished

by extension (posterior pelvic tilting) of the hip

j oi nt from the quadrupedal posture, the rest oc-

curs as extension (lordosis) of the l umbar spine.

This means t hat the pelvis is tilted anteriorly,

relatively speaking, in normal standing.

The antero-posterior tilt of the pelvis has a

major influence on the posture of the body since it

co-varies with the angle of the sacrum from which

the l umbar lordosis arises. An underst andi ng of

factors influencing tilt of the pelvis is therefore

essential for the analysis of post ure and post ural

load.

In figure 4, the pelvis is represented sagittally

with the hip j oi nt regarded as a fulcrum. The tilt

of the pelvis is the equilibrium position of the

moment s and count ermoment s exerted by the

muscular-ligamentous system which fixes the pelvis

on the hip j oi nt . The iliofemoral l i gament lies

anterior to the hip j oi nt and the ischiofemoral

ligament lies posterior to the j oi nt . In standing,

( a )

Erector Spinae

Anterior Superior /

Iliiac Spine ~ . /

k / Posterior Superior

Rectus Femoris t ( - " " ' - - ' - ' J

--%:+

I~liopsoas ~ I JJ

Pubic Body Ischial Tuberosity

(b)

Abdominals

Hip

Flexors

~ ~ 1 ~ Erect r Spinae

sor8

Fig. 4. Conceptual model of t he sagittal pelvis.

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture 7

these l i gament s are in moder at e tension, dur i ng

ext ensi on of the hi p all of t he l i gament s become

t aut whereas in fl exi on t hey relax. In standing, t he

i l i ofemoral l i gament prevent s t he pelvis f r om tilt-

ing post eri orl y i.e. it prevent s the t r unk f r om

' j ackkni f i ng' backwards over t he legs.

Dur i ng lateral r ot at i on of the hi p (t o st and wi t h

t he toes poi nt i ng out wards, for exampl e) t he ant e-

ri or l i gament s become t aut and the post er i or liga-

ment slackens. The opposi t e occurs duri ng medi al

r ot at i on (Kapandj i , 1970). Thi s may expl ai n why

Cyri ax (1924) hel d t hat walking with the toes

t ur ned out t oo much was a cause of excessive

ant er i or pelvic tilt in chi l dren (and hence excessive

l umbar lordosis). Thi s woul d sl acken t he post er i or

l i gament and tense t he ant er i or l i gament s resul t i ng

in a net increase in t he ant er i or moment act i ng on

t he hi p j oi nt and a mor e ant eri orl y tilted equi-

l i bri um posi t i on of t he pelvis. Thi s illustrates why

an analysis of foot posi t i on is essential to t he

analysis of post ur e and t he i mpr ovement of t he

design of workspaces.

Pelvic tilt is not t he onl y det er mi nant of spinal

curvat ure. Kapandj i (1970) describes how t he

art i cul ar facet of t he sacrum is subject to wide

vari at i on in humans. In t he mor e hori zont al l y

al i gned sacrum, t he spinal curves are pr onounced

- Kapandj i regards this as an over adapt at i on to

t he bi ped state. When t he spinal curves are less

pr onounced, the sacrum t ends t o lie mor e verti-

cal l y on the ilium. Thi s may expl ai n why measure-

ment s of pelvic tilt do not always correl at e with

measur ement s of l umbar cur vat ur e (Wal ker et al.,

1987), whereas measur ement s of sacral tilt do

(Bri dger et al., 1989a; 1990). Al t hough the mor e

vertically aligned sacrum with fl at t er spine does

occur in adults, it is mor e usual l y seen in chi l dren

and closely resembl es t he sacral or i ent at i on f ound

in pri mat es (Kapandj i , 1970).

I n neonat es, t he spi ne exhibits a single, ant eri -

orl y concave curve and vertical sacrum. Thi s

kyphosi s of the l umbar spi ne di sappears at about

13 mont hs of age and is repl aced by a l umbar

lordosis of increasing severity aft er the t hi rd year.

By t en years, the adul t st at e is assumed. When an

adul t stands, the l umbar lordosis suppor t s t he

upper body so as to mi ni mi se the bendi ng moment

on t he spi ne and t he line of gravi t y of t he superin-

cumbent body part s passes t hr ough t he facet j oi nt s

of L4 and L5 ( Kl ausen and Rasmussen, 1968).

Devel opment of t he bi pedal post ur e in chi l dren

suggests a recapi t ul at i on of phyl ogeny in ont og-

eny. The young child is physi cal l y unabl e t o st and

at first, par t l y because of an i nabi l i t y to ful l y

ext end t he knee and hi p and t he absence of a

l umbar lordosis. Crawl i ng is a pr ecur sor t o st and-

i ng in which hi p ext ensi on in t he quadr upedal

posi t i on is used for l ocomot i on. ( Raf t , 1962, re-

garded pr emat ur e st andi ng as a cause of mal devel -

opment of t he feet in children).

The muscles of the hip and t runk and the

mai nt enance of posture

The i mpor t ance of t he ant er i or gluteals in t he

lateral stabilisation of t he pelvis has al ready been

not ed. Fi gure 4 present s a sagittal view of t he hi p

and pelvis. The fl exor and ext ensor muscles of t he

hi p and t r unk pl ay a maj or rol e in t he mai nt e-

nance of the erect post ure. As descri bed above,

t he pelvis is fixed on the hi p by a syst em of

muscles and ligaments. The tilt of t he pelvis de-

pends on the equi l i bri um of t he moment s and

count er moment s exert ed by t he ant agoni st i c

muscles in this system. The one and t wo j oi nt hi p

flexors (iliopsoas and rect us femori s) and t he one

and t wo j oi nt hi p ext ensors (gluteus maxi mus and

t he hamst ri ngs) are of rel evance to ergonomi cs as

are t he abdomi nal and erect ores spi nae muscl es of

t he trunk. Cont r act i on of t he hi p fl exors ( on a

fixed f emur as in st andi ng) and t he erect ores spi nae

t ends to tilt t he pelvis forwards and exaggerat e t he

l umbar lordosis whereas t ensi on in the hi p ex-

t ensors and t he abdomi nal s t ends t o tilt t he pelvis

post eri orl y and r educe t he l umbar lordosis.

The spi ne itself l acks i nt r i nsi c st abi l i t y.

Nachems on (1966, 1968) not es t hat an i sol at ed

l i gament ous spi ne can onl y suppor t a l oad of 2 kg

pl aced on t op of t he first t horaci c vert ebrae. Kl an-

sen (1965) hel d t hat t he short, deep muscles of t he

back suppor t ed t he i ndi vi dual j oi nt s of t he spine.

The l ong back muscles were responsi bl e f or t he

stabilisation of t he spi ne as a whol e when t he line

of gravi t y of t he upper body par t s passed vent ral l y

t o the l umbosacral j oi nt . The ant er i or abdomi nal s

stabilised t he spine when t he line of gravi t y was

dorsal t o t he axis of movement of t he j oi nt .

Nachems on (1966, 1968) i nvest i gat ed t he role

of the vert ebral por t i on of t he iliopsoas muscl e

(psoas maj or) in t he ext ri nsi c st abi l i sat i on of t he

R.S. Bridger /Some fundamental aspects of posture

spine. He concl uded t hat , in addi t i on t o its func-

t i on as a hi p flexor, the psoas muscl e was i nvol ved

in t he st abi l i sat i on of t he l umbar spi ne part i cu-

l arl y in upri ght st andi ng and uns uppor t ed sitting

(i.e. wi t hout a backrest ). Psoas act i vi t y decr eased

when the t r unk was inclined f or war ds while act i v-

ity of the sacro-spi nal i s muscl es si mul t aneousl y

increased. Taken t oget her and recal l i ng the com-

ment s made previ ousl y about t he funct i on of

gl ut eus maxi mus, t he muscl es of the hi p and t r unk

can be seen as a syst em of synergi st s and

ant agoni st s which i nfl uence the shape of t he spi ne

in erect st andi ng and sitting t hr ough t hei r effect s

on the tilt of the pelvis as t hey act to stabilise the

upper body.

The abdomi nal muscl es (rect us abdomi ni s and

obl i que) and the t horaci c (i nt ercost al ) muscl es pl ay

a maj or role in stabilising t he spi ne when a wei ght

is lifted or car ded (in rel axed st andi ng, t hey are

el ect r omyogr aphi cal l y silent) accor di ng to the

cant i l ever anal ysi s of Morri s et al. (1961). The

cont r act i on of these muscl es pressuri ses the con-

t ent s of the t horax and t r unk and convert s t hem

i nt o a ppr oxi ma t e hydr aul i c and pne uma t i c

' s pl i nt s ' or cyl i nders capabl e of resisting some of

the fl exor mome nt on the spi ne and t herefore

reduci ng t ensi on in the ext ensors of the spine.

As pden (1989) pr opos ed a new mat hemat i cal

model of t he spi ne based on arch mechani cs. I n

this model , i nt r a- abdomi nal pressure is essent i al

for lifting heavy wei ght s in conj unct i on wi t h

l umbar lordosis. Empi ri cal l y, Or t engr en et al.

(1981) have demons t r at ed hi gh posi t i ve correl a-

t i ons bet ween measur es of i nt r a- abdomi nal and

i nt ra-di scal pressure and back muscl e activity. Thi s

does not necessari l y i mpl y t hat i nt r a- abdomi nal

pressure exerts an ext ensor mome nt about the

spine, however. As pden pr oposes t hat it appl i es a

compr essi ve stress t o t he convex surface of the

l umba r l ordosi s whi ch act s to stiffen the l umbar

spi ne and t her ef or e i ncreases its abi l i t y to with-

st and loads.

Postural faults and muscle balance

Kendal l et al. (1971) pr esent anal yses of pos-

t ural faul t s which i l l ust rat e the rol e of t he muscl es

of t he hip and t r unk in the mai nt enance of pos-

ture. They make consi der abl e use of t he concept

of ' mus cl e bal ance' in t he anal ysi s of post ure.

( a ) ( b )

! I

( c )

Fig. 5. Alignment of the spine, pelvis and hip in standing. (a)

Normal posture. (b) Excessive anterior pelvic tilt and hyper-

lordosis. The hip flexors and low back muscles are shortened

and the abdominals are lengthened and often weak. (c) 'Flat-

back' posture caused by excessive posterior pelvic tilt (hyperex-

tension of the hips). Sometimes caused by weak hip flexors.

(Adapted from Kendall et al., 1971.)

When a muscl e is weakened and its ant agoni st is

not , a st at e of i mbal ance is said t o occur. The

st ronger muscl e t hen short ens and t he weaker

el ongat es resul t i ng in a def or mi t y of t he post ur e of

t he j oi nt . Fi gur e 5 i l l ust rat es this usi ng exampl es

of i mbal ance in the hi p and t r unk muscul at ur e.

The al i gnment usual l y seen in heal t hy subj ect s is

depi ct ed in figure 5a. The l umba r l ordosi s and

t horaci c kyphosi s are easi l y di scerned. I n fi gure

5b, t he pelvis is tilted ant er i or l y (this ma y be

caused by an i mbal ance bet ween t he hi p fl exors

and l ow back muscl es on t he one hand and the

abdomi nal and hi p ext ensors on the ot her). A

compens at or y i ncrease in t he l umba r l ordosi s oc-

curs to mai nt ai n the t r unk in an erect posi t i on. I n

fi gure 5c the pel vi s is tilted post er i or l y and com-

pens at or y r educt i on of the l umba r l ordosi s occur s

accordi ngl y.

Gener al l y speaki ng, weakness resul t s in a l ack

of suppor t about a j oi nt and per mi t s a st at e of

def or mi t y whereas short ness creat es t he def or mi t y.

Def or mi t i es can also occur if weak muscl es are no

l onger abl e t o adequat el y oppos e gravi t y.

I n a clinical st udy, Fi sk and Bai gent (1981)

f ound t hat young pat i ent s wi t h back pai n fre-

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture 9

quent l y had stiffness in the lower thoracic spine

and this was related to ' t i ght ' hamst ri ng muscles

(i.e. in these patients, hip flexion with the knee

ext ended was limited to about 30 degrees due to

passive stretching of the hamst ri ngs which pre-

vents furt her flexion). They hypot hesi sed t hat the

tight hamstrings, by limiting hip flexion when the

knees are extended, woul d increase the stress on

the spine when bendi ng (i.e. flexion of the spine

woul d need to be increased to compensat e for the

lack of hip flexion when activities involving bend-

ing were carried out).

A small number of studies have been carried

out to investigate the ant hr opomet r y of the hip

and t runk muscul at ure and the pelvis and spine as

a linkage in heal t hy subjects. Toppenberg and

Bullock (1986) carried out mul t i pl e regression

analyses of thoracic and l umbar angles (of stand-

ing subjects), pelvic tilt and indices of muscle

length (obt ai ned by measuring ranges of passive

flexion and extension of the hip j oi nt and trunk)

of adolescent females. They f ound some signifi-

cant relationships between these variables, in par-

ticular, a negative correlation between the index of

hamst ri ng length (range of hip flexion with the

knee extended) and the l umbar lordosis. This sug-

gested that individuals with short (' t i ght ' ) ham-

strings had more pronounced l umbar lordoses t han

those with long hamst ri ngs - somewhat surprising

since the hamst ri ngs cause posterior pelvic tilting

which flattens, rat her t han accentuates, the l umbar

lordosis. This fi ndi ng was replicated by Bridger et

al. (1989b). They suggested t hat it was a statistical

artifact, the result of a positive correlation be-

tween the measures of hip flexion and extension

(the indices of hamst ri ng and iliopsoas length).

Theoretically, in standing, short (or ' t i ght ' )

iliopsoas muscles would t end to tilt the pelvis

forwards and accent uat e the l umbar lordosis. The

hamst ri ngs are not stretched in st andi ng and would

therefore not be expected to influence the tilt of

the pelvis. Similar findings were report ed by

Bridger et al. (1990). Their dat a furt her stresses

the role pl ayed by iliopsoas in det ermi ni ng stand-

ing post ure and post ural adapt at i on to di fferent

working positions.

This provides a clear theoretical j ust i fi cat i on

for the inclusion of footrests or footrails in the

design of workspaces for st andi ng operators. When

one foot is placed on an elevated footrail, the

correspondi ng hip j oi nt is slightly flexed and its

iliopsoas muscle shortened. Thi s tilts the pelvis

posteriorly and slightly reduces the l umbar lordo-

sis. Essentially, i nt ermi t t ent use of a foot rest by a

st andi ng operat or may help to prevent post ural

fixity of the l umbar spine and therefore reduce

fatigue or backpain. Grieco (1986) suggested t hat

post ural fixity in sitting may be a hazard since it

degrades nut ri t i onal exchange in the intervertebral

discs.

The concept ual model or the hi p/ pe l vi s / s pi ne

linkage present ed in figure 4 is not new.

Forrester-Brown (1930) emphasi sed the clinical

i mport ance of the tilt of the pelvis in det ermi ni ng

the posture of the spine. In ergonomics, Keegan

(1953) used this concept ual approach in his quali-

tative radi ographi c analysis of post ure related to

seating. It is not ewort hy t hat Keegan believed t hat

the application of a knowl edge of physiological

factors to chair design was i mpor t ant and an

i mprovement over the ' t r adi t i onal trial and error

and ant hropomet ri c measurement met hods of de-

signing seats' (Keegan, 1962). Mandal (1981, for

example) ext ended this work in advocat i ng the use

of chairs with forward sloping seats over the con-

ventional flat or rearward tilted seats. Recently,

Bridger et al. applied a similar approach to the

analysis of nine working positions, i ncl udi ng sit-

ting in a variety of ways. They concl uded t hat

postures can be anal ysed not onl y in terms of j oi nt

angles and dept h of spinal curves but also in terms

of the const rai nt i mposed on the pelvis and l umbar

spine by the degree of hip and knee flexion (i.e.

the funct i onal lengths of the one and two j oi nt

muscles of the hip and knee, their resting t one and

the extent to which t hey can be furt her l engt hened

in a part i cul ar working position).

Disturbances of muscle bal ance result in pos-

rural deviation. Initial weakness or tightness of a

muscle may cause faul t y al i gnment of a j oi nt and

vice versa. Cause and effect may be difficult to

distinguish except where some clear precipitating

factor such as paralysis or t r auma is extant. It is

less certain t hat incorrect workplace design and

postural fixity can lead to post ural faults, al-

t hough i mmobi l i sat i on of muscles in a short ened

position has been shown to cause st ruct ural short-

ening and stiffening of muscles over time (Her-

bert, 1988). Al t hough workspace redesign using

ergonomics is an appropri at e approach to the pre-

10 R.S. Bridget / S o me fundamental aspects of posture

vent i on of post ural faults at work, the det ai l ed

knowl edge of funct i onal anat omy possessed by t he

occupat i onal physi ot herapi st is essential at an idi-

opat hi c level for the diagnosis and t r eat ment of

individuals and t he redesign of t hei r workspaces.

Postural reflexes and posturai control

The erect human body is a tall st ruct ure wi t h a

nar r ow base of suppor t - its C. O. G. lies at mor e

t han hal f its t ot al height. In t erms of physics, t he

body is at t he mer cy of envi ronment al per t ur ba-

tions. In t erms of physiology, however, an adul t

wi t h ful l y-devel oped post ural reflexes is very sta-

ble (given t hat movement is not restricted).

Accordi ng to Mar t i n (1967), post ure is an active

process, its cont r ol depends on the existence of a

system of reflexes which are neurol ogi cal l y sep-

arat e f r om t he system which support s the trans-

mission of impulses for vol unt ar y movement and

f r om the ant i -gravi t y reflexes whi ch cause aut o-

mat i c braci ng of a limb when it is l oaded by body

weight.

The ant i -gravi t y reflexes are cent ered in t he

hi nd brai n (pons and medulla, Mart i n, 1967). Al-

t hough t hey are essential for the mai nt enance of

the upri ght post ure, t hey do not assist in the

mai nt enance of equilibrium. A second set of pos-

tural reflexes ( dependent on t he basal ganglia of

the mi d brai n) cont rol t he post ur e of the various

body part s in rel at i on to each ot her (post ural

fi xat i on of limbs, for exampl e) and the post ure of

the whol e body itself. The cerebel l um is also in-

vol ved in post ure in the co- or di nat i on of body

movement s.

The reflex cont rol of post ure (as distinct f r om

bot h low level reflex arcs such as the ' knee j er k'

reflex and vol unt ar y movement ) depends on bot h

intrinsic and extrinsic feedback. The l abyri nt hi ne

reflexes seem to be concer ned with pr ot ect i on

against mechani cal instability. Mar t i n (1967) not es

t hat peopl e devoi d of vest i bul ar funct i on exhi bi t ed

little appar ent disability pr ovi ded they were on a

stable base and obt ai ned visual feedback. Post ural

reflexes dependent on visual feedback are most l y

suppl ement ar y to pr opr i ocept i ve or l abyri nt hi ne

feedback (except t he reflex react i on to an obst acl e

in the pat h of mot i on). However, peopl e with

i mpai red somat i c and or l abyri nt hi ne feedback

exhi bi t part i cul ar disabilities when t hei r vision is

i mpai red (e.g. i nabi l i t y to mai nt ai n t he head erect

when bl i ndfol ded) and in some cases can onl y

funct i on nor mal l y when addi t i onal cues are given

(e.g. t hey can onl y walk when whi t e lines are

pai nt ed on t he fl oor or when gui ded by t he little

finger, Mart i n, 1967).

Ext ri nsi c and i nt ri nsi c f eedback are essential to

the mai nt enance of stable post ure. Some quad-

rupedal ani mal s can ' l ock' t hei r limbs to achi eve

stability at little energy cost (presumabl y, this is

one reason why horses can sleep st andi ng up). In

humans bi pedal stability is achi eved dynami cal l y.

In the sagittal plane, t he ant er i or and post er i or

muscles act as ant agoni st s t o keep t he C. O. G. of

the body wi t hi n t he small base of suppor t def i ned

by the posi t i on of t he feet. Post ural reflexes act

such that, for example, f or war d fl exi on of t he

t r unk ant eri or to t he base is accompani ed by

post eri or proj ect i on of t he but t ocks (the ankl e

j oi nt s pl ant arfl exi ng accordi ngl y). Loss of bal ance

post eri orl y is accompani ed by f or war d t hrust i ng

of the pelvis ( hyper ext ensi on of t he hi p j oi nt s) and

the arms to rest ore t he C. O. G.

Post ural st abi l i t y and post ural s way

In heal t hy subjects under less drast i c cir-

cumst ances, erect post ure is accompani ed by pos-

t ural sway. Thi s can be measur ed usi ng a force

pl at e and used t o eval uat e f unct i on in a vari et y of

medi cal compl ai nt s (e.g. strokes). Passive testing

can be suppl ement ed by active met hods in whi ch

destabilising forces are dehber at el y appl i ed at the

feet or waist ( Duncan et al., 1990). An ' ankl e

strategy' is used t o count er small per t ur bat i ons of

t he C. O. G. and a ' hi p st rat egy' t o count er large

per t ur bat i ons or when the suppor t surface is nar-

row (when worki ng in a conf i ned space or on a

nar r ow pl ank for example). For post er i or displace-

ments, tibialis ant er i or and t hen quadri ceps

femori s cont r act in t he ankl e st rat egy and t he

paraspi nal and hamst ri ng muscles in t he hip

strategy.

Losses of bal ance (i ncl udi ng slips, trips and

falls) are a maj or cause of work-rel at ed i nj ury

(Porri t t , 1985). A summar y of some of t he fact ors

which i nfl uence post ural sway and stability is

t herefore appropri at e.

Several fact ors i nfl uence post ur al st abi l i t y and

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture 11

sway in heal t hy subj ect s (see Ekdahl et al., 1989).

Age has been f ound to be rel at ed to sway in some

st udi es but not in ot hers. Vi si on is known t o be an

i mpor t ant st abi l i si ng f act or in mai nt ai ni ng the

erect st ance whereas severe heari ng loss has been

shown to cor r el at e wi t h i ncreased sway. Of t he

vari ous bal ance tests i nvest i gat ed by Ekdahl et al.,

st andi ng on one leg while bl i ndf ol ded was the

mos t di ffi cul t ( i mpossi bl e for subj ect s over 55

years) and st andi ng on one leg wi t hout a bl i ndf ol d

was mor e di ffi cul t t han st andi ng wi t h the feet

t oget her wi t h a bl i ndfol d.

These results are not surpri si ng in vi ew of the

r educt i on in t he size of t he base of suppor t , in-

creased muscl e coor di nat i on ( r ecr ui t ment of t he

hi p abduct or s to mai nt ai n the C. O. G. over a single

foot ) and loss of vi sual f eedback br ought about by

this test. Some i nt erest i ng pract i cal i mpl i cat i ons

are, for exampl e, t hat oper at i ng foot pedal s in a

st andi ng posi t i on woul d be cont r ai ndi cat ed, par -

t i cul arl y under poor lighting. Ekdahl et al. al so

obser ved t hat f emal e subj ect s had bet t er bal ance

t han men, possi bl y at t r i but abl e to a l ower C. O. G.

Post ural sway anal ysi s may be of use in ergo-

nomi cs to assist in t he desi gn of l oads f or manual

mat er i al s handl i ng and in wor kspace desi gn gener-

ally, par t i cul ar l y where t here is a l ack of space f or

t he feet and hence i ncreased de ma nd on the pos-

t ural cont r ol syst em.

Fi nal l y, post ur e ma y var y accor di ng to the level

of neur al act i vat i on. Mar ek and Nor owol (1986)

i nvest i gat ed changes in sitting post ur e dependi ng

on t he level of st i mul at i on by t he task. Over st i mu-

l at i on was accompani ed by a decrease in head and

t r unk i ncl i nat i on and under st i mul at i on by an in-

crease in t r unk and head i ncl i nat i ons dur i ng t he

first t wo hour s of work. They at t r i but ed t hese

fi ndi ngs to di fferences in muscl e t one due t o

changes in neural act i vat i on (faci l i t at i on vi a pat h-

ways in the ret i cul ar f or mat i on) .

Behavioural aspects of postural control

Demps t er (1955) vi ewed the body as an open-

chai n syst em of links. Each j oi nt of the body has a

f r eedom for angul ar mot i on in one or mor e di rec-

tions. A compl ex linkage, such as t hat bet ween t he

shoul der, ar m and hand has ma ny degrees of

f r eedom of movement and power t r ansmi ssi on is

i mpossi bl e wi t hout accessory st abi l i sat i on of j oi nt s

by muscl e act i on. For exampl e, supi nat i on of t he

wrist may be requi red to t ur n a door handl e but

this is onl y possi bl e if t he el bow and shoul der

j oi nt s are st abi hsed and can count er t he r eact i on

at t he hand- handl e i nt erface. When anal ysi ng t he

wor kl oad or onset of fat i gue associ at ed wi t h t he

per f or mance of a task, an a t t e mpt t o di st i ngui sh

bet ween t he l oad i mposed by t he wor k i t sel f and

the l oad i mposed by t he r equi r ement s f or post ur al

st abi l i sat i on ma y be appr opr i at e - ma n y in-

dust ri al t asks i nvol ve t he mani pul at i on of obj ect s

whose mass is negligible c ompa r e d t o t he mas s of

the oper at or and his mai n body segment s.

Post ural reflexes exist f or t he compl ex cont r ol

of j oi nt forces whi ch occur dur i ng al mos t all of

our dai l y activities. Na c he ms on (1966) bel i eved

t hat t he psoas muscl e was i nvol ved in post ur e

mai nt enance quot i ng De mps t e r ' s vi ew t hat when

t he body f or ms a cl osed-chai n syst em of l i nks to

exert forces on its envi r onment , t he t r unk and

l i mb muscl es do not di rect l y exert forces, r at her

t hey mai nt ai n j oi nt post ur es such t hat body wei ght

exert s an effect i ve moment . Thi s mechani s m un-

doubt edl y makes possi bl e t hose act i vi t i es in whi ch

the body pr oduces very l arge forces on its envi r on-

ment or in whi ch j oi nt s or ext ernal obj ect s un-

der go r api d accel erat i on t hr ough ' pi vot i ng' ac-

t i ons (as in t hr owi ng a j avel i n, or swi ngi ng a gol f

club).

Br ant on (1969) used t he body- l i nk concept to

eval uat e t he comf or t of t r ai n seat s usi ng obser va-

t i onal dat a on sitting behavi our . An open- chai n

syst em of body links can behave in unpr edi ct abl e

ways when subj ect to i nt er nal and ext ernal forces.

The pr i me f unct i on of a seat is t o s uppor t body

mass agai nst t he forces of gravi t y. A second func-

tion, whi ch was emphasi sed by Br ant on, was t o

st abi l i se the open- chai n syst em. I n t he absence of

ext ernal st abi l i sat i on, t oni c muscl e act i vi t y is re-

qui red whi ch l eads t o di scomf or t . Behavi our s such

as fol di ng t he ar ms and crossi ng t he legs are

post ur al st rat egi es whi ch t ur n open- chai ns i nt o

appr oxi mat e cl osed chains, st abi l i sed by fri ct i on.

The comf or t of a seat, t herefore, depends on t he

ext ent t o whi ch it per mi t s mus cul ar r el axat i on

while st abi l i si ng t he open- chai n of body links.

Br ant on' s anal ysi s r emai ns novel (in t he

aut hor ' s opi ni on) and is of val ue in post ur e anal y-

sis since t he physi cal wor kl oad of ma ny t asks can

be r educed if t he oper at or st abi l i ses a body par t

12 R.S. Bridget / S o me fundamental aspects of posture

by formi ng t empor ar y closed chains wi t h his

workspace (e.g. upper body weight can be used t o

stabilise a forearm, hand and component resting

on t he worksurface while the ot her hand uses a

tool t o work on t he component ). Many post ural

strategies for rel axat i on are cul t ural l y det ermi ned.

A famous exampl e is t he ' st ork-l i ke' stance of the

nilotic herdsmen of East Afri ca (st andi ng on one

leg with the sole of the opposi t e foot resting on

the knee of the weight-bearing leg). A bri ef con-

si derat i on of some cross-cultural aspects of pos-

t ure is t herefore in order.

Cross-cultural variation in postural habits

Man is capabl e of appr oxi mat el y 1000 comfor-

table static post ures (Hewes, 1957). In most cul-

tures, however, onl y a subset of these are pract i ced

due t o tradition, cl i mat e and terrain, cl ot hi ng de-

sign and the met hods of work. The most widely

researched post ure is undoubt edl y st andi ng fol-

lowed by t he west ern ' 90-degree' sitting post ure,

as well as its reclining vari ant s and the furni t ure

used to suppor t it (see Mandal , 1981, for a cri t i que

of 90-degree sitting). The bipedal, upri ght stance

is universal across cultures and can be regarded as

f undament al in an anat omi cal sense. The same

cannot be said for sitting in chairs. This has its

origin in Anci ent Gr eece and Egypt as a high

status post ure. The rest of t he popul at i on appears

to have sat on the fl oor or on low, sloping stools

(Mandal , 1984). A common posture, worldwide, is

t he deep squat (regarded as vulgar by the Anci ent

Greeks, which may explain why it is not pract i sed

in count ri es i nfl uenced by hellenistic culture).

However, millions of peopl e in many part s of

Asia, Africa, Lat i n Ameri ca and Oceani a cust om-

arily work and rest in this posi t i on - t he C. O. G.

of t he body is low and over the feet, the hips and

knees are al most fully flexed, t he hamst ri ngs and

quadri ceps muscles are t owards t he mi ddl e of

t hei r range, t he iliopsoas are short ened and the

gluteals are lengthened. The t r unk is flexed and

inclined ant eri orl y t owards the thighs. This pos-

t ure is similar to t he habi t ual resting posi t i on of

the chi mpanzee and is easy for young chi l dren of

any cul t ure t o adopt . Adul t s not accust omed t o it

find it difficult however - one reason bei ng t hat

t hey lack sufficient dorsiflexion at the ankl e to get

the C. O. G. of the body over t he feet and t her ef or e

t end to fall backwards.

Cross-legged sitting is f ound in Nor t h Africa,

the Mi ddl e East, India, Sout h East Asia and In-

donesi a and also Korea, Japan and Polynesia. It is

depi ct ed in anci ent Mayan sculptures and in t he

pot t er y of many tribes of Nor t h and Sout h

America. Convent i on, cl ot hi ng and cold, damp

floors restrict its use in west ern cul t ure (al t hough

it is a common post ure in school chi l dren), but

most peopl e are able to sit in this way. The hips

are flexed, abduct ed and l at eral l y r ot at ed wi t h t he

knees resting on t he f oot of t he opposi t e leg. The

two-joint muscles of the hi p are rel axed as is

iliopsoas and body weight is bor n by t he ischia

and not the coccyx. (In Indi a t here are many

vari at i ons of this basic position. Sen, 1984, sum-

marises some of the benefits. )

Long sitting (on t he fl oor wi t h a ni net y-degree

t runk-t hi gh angle and knees ext ended) is a com-

mon worki ng and resting post ur e among women

in Africa, Melanesia, Sout h East Asia and I ndi an

Nor t h West America. Bridger et al. (1990) demon-

st rat ed t hat this post ure is ext r emel y stressful for

westerners unaccust omed to it (part i cul arl y males)

because of hamst ri ng tightness, whi ch causes ex-

t reme post eri or pelvic tilting and l umbar flexion.

Sitting on the heels wi t h t he knees resting on

t he fl oor is a formal sitting post ur e f or bot h men

and women in Japan. It is t he posi t i on for pr ayi ng

in the Islamic world. In Africa, Mexi co and part s

of Sout h East Asia it is mai nl y used by women.

Most adults in west ern cul t ure can at t ai n this

post ure even if unpract i sed, except t hose wi t h

overdevel oped or tight quadri ceps muscles or knee

injuries. Of t he ni ne sitting and st andi ng post ures

investigated by Bridger et al. (1990) this was the

post ure of least const r ai nt of t he hi p j oi nt wi t h the

l umbar spine and pelvis in t he mi ddl e of t hei r

ranges. Sitting on t he fl oor is general l y unaccept a-

ble in west ern society and it is i nt erest i ng to

observe t hat kneeling has recent l y been i mpl e-

ment ed in a mor e accept abl e f or m (t he ' Bal ans'

chair) - as a piece of f ur ni t ur e whi ch hft s t he user

of f the fl oor t o desk height (for eval uat i ons of this

concept see Dr ur y and Fr ancher , 1985; Fr ey and

Tecklin, 1986; Bridger, 1988).

Post ures for lifting and st oopi ng also var y across

cultures. In Africa, women t radi t i onal l y st oop to

pi ck up obj ect s and t o car r y out activities such as

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture 13

gardeni ng. The knees r emai n ext ended and t he

t runk-t hi gh angle of over 90 degrees is achi eved by

flexing the hips. Li t t l e l umbar flexion seems to

t ake place. Most west erners are unabl e t o st oop in

this way pr obabl y due to tight hamstrings. Fl oyd

and Silver (1955) and Ki pper s and Parker (1984)

observed t hat in t r unk fl exi on f r om standing, t he

erect ores spinae muscles exhi bi t electrical silence

at 60% of t he t ot al hi p and 90% of the t ot al

vert ebral flexion requi red t o st oop, body weight

bei ng suppor t ed by t he post er i or ligaments of t he

vert ebral col umn. The st oop met hod of lifting is

general l y regarded as hazar dous since it i mposes a

great er moment at t he l umbosacral j oi nt t han the

pr ef er r ed squat lift ( Gr i eve and Pheasant , 1982). It

is di ffi cul t t o under st and why t he st oop met hod is

habi t ual l y used in Afri ca i f it is hazardous, unless

t he ability t o avoi d l umbar fl exi on when the hips

are flexed confers some prot ect i on. (It may be t hat

with t he head bel ow t he hi p j oi nt s and straight

spine, the component of force al ong t he di rect i on

of t he spi ne exerts t ract i on on t he spine and

reduces disc pressure. )

Several cross-cul t ural investigations of the inci-

dence of spinal pat hol ogy have been carri ed out.

Fahr ni and Tr ueman (1965) compar ed the inci-

dence of disc space narrowi ng and hyper t r ophi c

change in Nor t h Amer i cans and Eur opeans and a

j ungl e-dwel l i ng t ri be in India. In all groups, l umbar

degener at i on i ncreased with age, but the t rends

were st eeper for t he west ern groups t han t he In-

di an tribe. The i nci dence of disc space nar r owi ng

was much less amongst t he Indi ans and was har dl y

age-rel at ed at all. Fahr ni and Tr ueman not ed t hat

t he spines of horses, cows, dogs, camels and

giraffes degenerat e at levels where the mechani cal

st rai n is great est (t he cervi co-t horaci c regi on of

camel s and giraffes, t he l ower t horaci c level in t he

basset hound and dachshund dog and the apex of

t he l umbar spi ne in humans). They observed t hat

the I ndi an t ri be habi t ual l y squat t ed, avoi di ng pos-

t ures in which a l umbar lordosis was ret ai ned, and

suggested t hat t he habi t ual l ordot i c post ures of

west ern cul t ure cont r i but ed to disc degenerat i on.

Fi ndi ngs such as these are di ffi cul t t o i nt er pr et

because of t he number of fact ors involved. Spinal

pat hol ogy is not always f ound t o be l ower in

non-west ern cul t ures ( Tower and Prat t , 1990, ob-

served a hi gher i nci dence of spondyl osi s and

spondyl ol i st hesi s in rural Eski mos t han in ur ban

Eski mos or bl ack or whi t e popul at i ons). Clearly,

t he cross-cultural st udy of post ur e and post ural

habi t s is pot ent i al l y of i mmense val ue in under -

st andi ng t he high i nci dence of occupat i onal

muscul oskel et al di sorders in t he i ndust ri al i sed

world.

S o m e p r a c t i c a l i m p l i c a t i o n s

The l oweri ng of t he C. O. G. of t he body was an

i mpor t ant stage in the evol ut i onar y devel opment

of bipedalism. In ont ogeny, it is accompani ed by

i ncreased post ural stability and devel opment of

adul t gait. Al t hough a great deal of research has

been done on lifting, less at t ent i on has been pai d

to carrying. Gr i eve and Pheasant (1982) argue t hat

hol di ng a weight close to t he body is advi sabl e to

minimise t he moment about t he l umbo-sacral j oi nt .

Ther e woul d appear t o be t heoret i cal suppor t for

t he not i on t hat the C. O. G. of t he body plus l oad

shoul d not be raised when an obj ect is carri ed or

hel d because an increase in t he hei ght of t he

C. O. G. increases the l oad on t he muscles (such as

t he gluteals), whi ch stabilise t he t r unk and may

increase post ural sway and hast en t he onset of

fatigue. It may be hypot hesi sed t hat t he C. O. G. of

t he l oad shoul d be no hi gher t han t he hips, par-

ticularly when walking or st andi ng on uneven

ground. A yoke carri ed over t he shoul ders wi t h the

l oad suspended symmet ri cal l y can satisfy this re-

qui r ement but it increases t he fl exor moment on

t he t r unk as refl ect ed by i ncreased erect ores spi nae

activity (Kl ausen, 1965). Moder n rucksacks trans-

mi t t he l oad t hr ough the iliac crests via a hi p

strap. Thi s met hod of l oad carri age increases t he

ext ensor moment on t he t runk, whi ch is opposed

by t he iliopsoas muscles (Kl ausen, 1965). It is

not ewor t hy t hat in Kl ausen' s original paper, pho-

t ographs of t he above t wo carryi ng met hods show

al most i dent i cal bodi l y post ures, el ect r omyo-

graphi cal analysis bei ng r equi r ed t o disclose the

bi omechani cal di fference bet ween them. In Afri ca,

women t radi t i onal l y car r y young chi l dren l ow on

t hei r backs.

The l umbar lordosis is f undament al t o erect

standing, but it depends on t he angl e of t he sacr um

and t he tilt of t he pelvis. This, in t urn, depends on

t he equi l i bri um of moment s and count er moment s

14 R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture

exerted on the pelvis by the musculo-ligamentous

system which controls movement of the hip and

therefore on the angles of hip and knee flexion

(see Brunswic, 1984). A l umbar angle of 20-30

degrees is normal in European subjects when

st andi ng but is beyond the range of vol unt ary

movement of the hip and pelvis of males in 90-de-

gree sitting and is at the extreme of the vol unt ary

range of bot h males and females in sitting pos-

tures which do not constrain the pelvis (e.g. kneel-

ing and sitting in forward sloping chairs, Bridger

et al., 1990).

Postures other t han st andi ng are not funda-

ment al in an anat omi cal sense. Societal factors

such as t radi t i on and technology can shape the

development of postural reflexes and j oi nt mobili-

ties t hrough their effects on habi t ual activities.

The ' 90-degree' sitting posture, long used as a

model for the ergonomic design of workspaces,

has received much criticism recently (Mandal ,

1981, for example). In view of the above discus-

sion, this posture would appear to be atavistic

(figure 1) and has been replaced by anat omi cal l y

more sophisticated alternatives (Corlett and Ek-

lund, 1984 and Gregg and Corlett, 1988, for exam-

ple). A young child has the ability to at t ai n all of

the resting positions practiced t hroughout the

world, but usually practises onl y a subset. In the

present aut hor' s opinion, the at t ai nment of a wider

post ural repertoire in yout h may be of benefit in

later life. The ergonomics literature cont ai ns infor-

mat i on on ant hr opomet r y and workspace design

much of which is based on a limited set of pos-

tural models - those which are found amongst

people who grew up in a western industrial milieu.

Whet her other postures would be more ap-

propriate, particularly for i mpl ement at i on in de-

veloping countries, is wort hy of further investiga-

tion which should lead to a better underst andi ng

of the true limitations and possibilities of human

anat omy.

Acknowledgements

The aut hor would like to t hank the Medical

Research Council of South Africa, Professor M.

Henneberg, Mrs. D. Orkin, Professor G. G. Jaros

and Dr. H. Gol dberg for their support.

References

Aghazadeh, F., Latif, N.T. and Mital, A., 1989. Guidelines for

preventing hand tool related accidents and illnesses. Ergo-

nomics SA, 1(1): 2-9.

Aspden, R.M., 1989. The spine as an arch. A new mat hemat i -

cal model. Spine, 14(3): 266-274.

Branton, P., 1969. Behaviour, body mechanics and discomfort.

Ergonomics, 12(2): 316-327.

Bridger, R.S., 1988. Postural adapt at i ons to a sloping chai r and

worksurface. Human Factors, 30(2): 237-247.

Bridger, R.S., von Eisenhart-Rothe, C.C. and Henneberg, M.,

1989a. Effects of seat slope and hi p flexion on spinal angles

in sitting. Human Factors, 31(6): 679-688.

Bridger, R.S., Wilkinson, D. and Van Houweninge, T., 1989b.

Hip j oi nt mobility and spinal angles i n st andi ng and in

different sitting postures. Human Factors, 31(2): 229-241.

Bridger, R.S., Orkin, D. and Henneberg, M., 1990. Interrela-

tionships between t he spine, pelvis and hip: Measurement s

in st andi ng and in different working positions. Submi t t ed

to Ergonomics SA.

Brunswic, M., 1984. Ergonomics of seat design. Physiotherapy,

70(2): 40-43.

Charteris, J., Wall, J.C. and Not t rodt , J.W., 1982. Pliocene

homi ni d gait: New i nt erpret at i ons based on available

foot pri nt dat a from Laetoli. Ameri can Journal of Physical

Anthropology, 58: 133-144.

Corlett, E.N. and Eklund, J.A.E., 1984. How does a backrest

work? Applied Ergonomics, 15(2): 111-114.

Corlett, E.N., Wilson, J. and Manneni ca, I., (Eds.), 1986. The

Ergonomics of Worki ng Postures. Taylor and Francis,

London.

Cyriax, E.F., 1924. On the antero-posterior tilt of the pelvis, its

variations and their clinical significance in children. British

Journal of Chi l dren' s Disease, 21: 279-283.

Dempster, W.T., 1955. The ant hropomet ry of body action.

Annal s of t he New York Academy of Sciences, 63: 559-585.

Drury, C.G. and Francher, M., 1985. Eval uat i on of a forward-

sloping chair. Applied Ergonomics, 16: 41-47.

Duncan, P.W., Studenski, S., Chandler, J., Bloomfield, R. and

LaPointe, L.K., 1990. Electromyographic analysis of pos-

tural adjustments i n two met hods of bal ance testing. Physi-

cal Therapy, 70(2): 88-96.

Ekdahl, C., Jarnlo, G.B. and Andersson, S.I., 1989. St andi ng

bal ance in healthy subjects. Scandi navi an Journal of Re-

habi l i t at i on Medicine, 21: 187-195.

Fahrni , W.H. and Trueman, G.E., 1965. Comparat i ve radio-

logical study of the spines of primitive popul at i on wi t h

Nor t h Americans and Nor t her n Europeans. The Journal of

Bone and Joi nt Surgery, 47-B(3): 552-555.

Farfan, H.F., 1978. The bi omechani cal advant age of lordosis

and hip extension for upright activity: Man as compared

with ot her anthropoids. Spine, 3(4): 336-342.

Fisk, J.W. and Baigent, M.L., 1981. Hamst ri ng tightness and

Scheuermann' s disease. Ameri can Journal of Physical

Medicine, 60(3): 122-125.

Floyd, W.F. and Silver, P.H.S., 1955. The funct i on of t he

erectores spinae muscles in certain movement s and postures

i n man. Journal of Physiology, 129: 184-203.

R.S. Bridger / Some fundamental aspects of posture 15

Forrester-Brown, M.F., 1930. Improvement of posture. The

Lancet, July 12: 115-117.

Frey, J.F. and Tecklin, J.S., 1986. Compari son of l umbar

curves when sitting on a Wesmofa Balans Multichair, on a

conventional chair and standing. Physical Therapy, 66:

1365-1369.

Gregg, H.D. and Codet t , E.N., 1988. Developments in t he

design and evaluation of industrial seating. In: Designing a

Better World, Proc. 10th Conference of the Int ernat i onal

Ergonomics Association, edited by A.S. Adams, R.R. Hall,

B.J. McPhee and M.S. Oxenburgh, Ergonomics Society of

Australia Inc.

Grieco, A., 1986. Sitting posture: An ol d probl em and a new

one. Ergonomics, 29(3): 345-362.

Grieve, D. and Pheasant, S., 1982. Biomechanics. In: W.T.

Singleton (Ed.), The Body at Work. Cambri dge University

Press, Cambridge.

Herbert, R., 1988. The passive mechanical properties of muscle

and their adapt at i ons to altered pat t erns of use. The

Aust ral i an Journal of Physiotherapy, 34(3): 141-149.

Hewes, G.W., 1957. The anthropology of posture. Scientific

American, 196(2): 122-132.

Jungers, W.L., 1982. Lucy' s limbs: Skeletal allometry and

locomotion in Australopithecus afarensis. Nature, 297, June,

676-678.

Kapandji, I.A., 1970. The physiology of the joints, Vol. 2,

lower limb. Churchill and Livingstone, Edi nburgh and

London.

Keegan, J.J., 1953. Alterations of the l umbar curve related to

post ure and seating. Journal of Bone and Joi nt Surgery,

35-A: 589-603.

Keegan, J.J., 1962. Evaluation and i mprovement of seats. In-

dustrial Medicine and Surgery, April: 137-148.

Kendall, H.O., Kendall, F.P. and Wadsworth, G.E., 1971.

Muscles: Testing and function. Second Edition, The Wil-

liams and Wilkins Company, Baltimore, MD.

Kilbom, A., 1988. Int ervent i on programmes for work-related

neck and upper l i mb disorders - Strategies and evaluation.

In: A.S. Adams, R.R. Hall, B.J. McPhee and M.S. Oxen-

burgh (Eds.), Designing a Better World; Proc. 10th Con-

ference of the Int ernat i onal Ergonomics Association Ergo-

nomics Society of Australia Inc.

Kippers, V. and Parker, A.W., 1984. Posture related to myoe-

lectric silence of erectores spinae duri ng t runk flexion.

Spine, 9(7): 740-775.

Klausen, K., 1965. The form and function of the loaded human

spine. Act a Physiologica Scandinavica, 65: 176-190.

Klausen, K. and Rasmussen, B., 1968. On the location of the

line of gravity in relation to L5 in standing. Act a Physio-

loglca Scandinavica, 72: 45-52.

Lovejoy, C.O., 1988. Evolution of human walking. Scientific

American, November, 82-89.

Mandal , A.C., 1981. The seated man (Homo Sedens). The

seated work position: Theory and practice. Applied Ergo-

nomics, 12: 19-26.

Mandal, A.C., 1984. The seated man (Homo Sedens). Taarbaek

Strandvej 49 (DK) 2930, Kl ampenborg, Denmark.

Marek, T. and Norowol, C., 1986. The influence of under- and

over-stimulation on sitting posture. In: E.N. Corlett, J.

Wilson and I. Manneni ca (Eds.), The Ergonomics of Work-

ing Postures. Taylor and Francis, London.

Martin, J.P., 1967. The basal ganglia and posture. Pi t man

Medical Publishing Co. Ltd., London.

McHenry, H.M. and Temerin, L.A., 1979. The evolution of

homi ni d bipedalism: Evidence from t he fossil record.

Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 22: 105-131.

Morris, J.M., Lucas, D.B. and Bresler, M.S., 1961. Role of the

t runk in stability of t he spine. Journal of Bone and Joi nt

Surgery, 43-A (3): 327-351.

Nachemson, A., 1966. Electromyographic studies of the

vertebral port i on of the psoas muscle. Act a Ort hopaedi ca

Scandinavica, 37: 177-190.

Nachemson A., 1968. The possible i mport ance of the psoas

muscle for stabilisation of t he l umbar spine. Act a Ort ho-

paedica Scandinavica, 39: 47-57.

Nachemson, A., 1976. The l umbar spine: An ort hopaedi c chal-

lenge. Spine, 1(1): 59-70.

Napier, J., 1967. The ant i qui t y of human walking. Scientific

American, April, 57-67.

Ortengren, R., Anderson, G.B. and Nachemson, A.L., 1981.

Studies of the relationships between l umbar disc pressure,

myoelectric back muscle activity and i nt ra-abdomi nal (in-

tragastric) pressure. Spine, 6: 98-103.

Porritt, The Rt. Hon. Lord., 1985. Slipping, t ri ppi ng and

falling: Familiarity breeds contempt. Ergonomics, 28(7):

947-948.

Raft, J., 1962. Cause of maldevelopment of the feet of the

preambul at ory child. Current Podiatry, 2(1): 20-23.

Robinson, J.T., 1972. Early homi ni d post ure and locomotion.

Chicago University Press, Chicago, IL.

Sen, R.N., 1984. Application of ergonomics to industrially

developing countries. Ergonomics, 27(10): 1021-1032.

Tobias, P.V., 1982. Man, the t ot t eri ng biped. Commi t t ee of

Postgraduate Medical Education, The University of New

South Wales.

Toppenberg, R.M. and Bullock, M.I., 1986. The i nt errel at i on

of spinal curves, pelvic tilt and muscle lengths in the

adolescent female. The Aust ral i an Journal of Physiother-

apy, 32(1): 6-11.

Tower, S.S. and Pratt, W.B., 1990. Spondylolysis and associ-

ated spondylolisthesis in Eskimo and At habascan popula-

tions. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 250:

171-175.

Walker, M.L., Rothstein, J.M., Finucane, S.D. and Lamb,

R.L., 1987. Relationships between l umbar lordosis, pelvic

tilt and abdomi nal muscle performance. Physical Therapy,

67(4): 512-515.

Zi hl man, A. and Brunker, L., 1979. Homi ni d bipedalism: Then

and now. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 22: 132-162.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Beyond Legendary Abs PDFDocument25 pagesBeyond Legendary Abs PDFMike100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Chapmans ReflexesDocument10 pagesChapmans ReflexesNickosteo100% (9)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- P. Ratan Khuman M.P.T. (Ortho & Sports)Document56 pagesP. Ratan Khuman M.P.T. (Ortho & Sports)Amogh Pandit100% (1)

- PRI Integ For Pediatrics (Nov 2020) - Complete ManualDocument208 pagesPRI Integ For Pediatrics (Nov 2020) - Complete Manualzhang yangNo ratings yet

- Organization of The Body: Lab Report 8Document5 pagesOrganization of The Body: Lab Report 8larry machonNo ratings yet

- Atlas Do Prof RAZ PDFDocument335 pagesAtlas Do Prof RAZ PDFKayoNo ratings yet

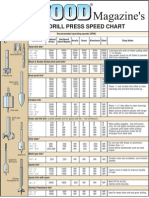

- Drill Speed ChartDocument2 pagesDrill Speed ChartArmySGT100% (2)

- Knoll - Office Ergonomics HandbookDocument20 pagesKnoll - Office Ergonomics HandbookEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Digestive System: by Achmad AminuddinDocument127 pagesDigestive System: by Achmad AminuddinRizkaKhaerunnisaNo ratings yet

- Visceral Manipulation in Osteopathy Eric Hebgen.11867 3pancreasDocument5 pagesVisceral Manipulation in Osteopathy Eric Hebgen.11867 3pancreasIoan Andra50% (4)

- Operative SurgeryDocument119 pagesOperative SurgerySubhrajyoti Banerjee100% (2)

- Spinal Anatomy & Surgical ApproachesDocument37 pagesSpinal Anatomy & Surgical Approachestachyonemc2No ratings yet

- LumbotomiDocument14 pagesLumbotomiazka novriandiNo ratings yet

- BauhausDocument83 pagesBauhausEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Ranjan - Lessons From Bauhaus, Ulm and NID PDFDocument15 pagesRanjan - Lessons From Bauhaus, Ulm and NID PDFEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Design For Utility, Sustainability and Societal Virtues: Developing Product Service SystemsDocument8 pagesDesign For Utility, Sustainability and Societal Virtues: Developing Product Service SystemsEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Ketley - Dieter Rams PDFDocument20 pagesKetley - Dieter Rams PDFEduardo Diestra0% (1)

- Vergragt, Brown - Innovation For SustainabilityDocument14 pagesVergragt, Brown - Innovation For SustainabilityEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Bursthaler - Universal DesignDocument4 pagesBursthaler - Universal DesignEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- University of LeicesterDocument12 pagesUniversity of LeicesterEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- ASD - When Sitting Correctly MattersDocument4 pagesASD - When Sitting Correctly MattersEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Bumax EngDocument56 pagesBumax EngEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Autoprogettazione Revisited Instructions WebDocument13 pagesAutoprogettazione Revisited Instructions WebDebrayandoNo ratings yet

- Instructables - Making A Touch Sensitve On Off Circuit With Bare Paint and A 666 Timer ICDocument6 pagesInstructables - Making A Touch Sensitve On Off Circuit With Bare Paint and A 666 Timer ICEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Gold, Silver and Bronze: Universal Design Features in HousesDocument9 pagesGold, Silver and Bronze: Universal Design Features in HousesEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- Pons Hepatis of Quadrate Lobe A Morphogical Variation of LiverDocument3 pagesPons Hepatis of Quadrate Lobe A Morphogical Variation of LiverEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- DifdgDocument54 pagesDifdgMarina Ivosevic MilosavljevicNo ratings yet

- Common Conditions of The Lumbar SpineDocument4 pagesCommon Conditions of The Lumbar SpineJames KNo ratings yet

- Done BY: Supervised BY: Sara Al-Ghanem 208009915: Dr. M. YasserDocument43 pagesDone BY: Supervised BY: Sara Al-Ghanem 208009915: Dr. M. YasserNicole LamNo ratings yet

- Mechanism of Normal Labour PDFDocument17 pagesMechanism of Normal Labour PDFGabriel ZuñigaNo ratings yet

- 13 ADocument14 pages13 ABruno100% (1)

- Emilio Aguinaldo College: School of NursingDocument3 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo College: School of NursingGrace CabilloNo ratings yet

- Kartu Hapalan Osteology Anatomy 2018: Nama: .. NIM: .. PembimbingDocument8 pagesKartu Hapalan Osteology Anatomy 2018: Nama: .. NIM: .. PembimbingzannubanabilahNo ratings yet

- Acetabulum Fractures - Classification and Management - Emile LetournelDocument26 pagesAcetabulum Fractures - Classification and Management - Emile LetournelThanat AuwattanamongkolNo ratings yet

- Integrated Anatomy: Imaging: of The SpineDocument13 pagesIntegrated Anatomy: Imaging: of The SpineFlo RenceNo ratings yet

- Abdo Pelvis - Lecture 01 - Anterior Abdominal WallDocument24 pagesAbdo Pelvis - Lecture 01 - Anterior Abdominal Wallsurgery 1No ratings yet

- Bones - LabDocument24 pagesBones - LabJhom Andrei Apolinar100% (1)

- Finals Cardiovascular SystemDocument20 pagesFinals Cardiovascular SystemgabbypeigNo ratings yet

- Angiology Lecture 2Document5 pagesAngiology Lecture 2আহানাফ তাহমিদ শব্দNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology-Intestinal ObstructionDocument2 pagesAnatomy and Physiology-Intestinal ObstructionRaisa Robelle Quicho75% (8)

- LUNG-OVERVIEW (Autosaved)Document132 pagesLUNG-OVERVIEW (Autosaved)Thivashinie Kandy Nazan VelloNo ratings yet

- The Human Muscles: Lectured by Bien Eli Nillos, MD Reference: Gray's AnatomyDocument158 pagesThe Human Muscles: Lectured by Bien Eli Nillos, MD Reference: Gray's Anatomybayenn100% (1)

- Female Genitalia and RectumDocument3 pagesFemale Genitalia and Rectumadrian lozanoNo ratings yet

- Spinal and Epidural Anesthesia: Kenneth Drasner and Merlin D. LarsonDocument32 pagesSpinal and Epidural Anesthesia: Kenneth Drasner and Merlin D. LarsonAngky SatriawanNo ratings yet