Professional Documents

Culture Documents

13 Dil Kuma Limbu - 1336385427cmlb

Uploaded by

Mishal LimbuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13 Dil Kuma Limbu - 1336385427cmlb

Uploaded by

Mishal LimbuCopyright:

Available Formats

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF LIMBU ON

ECOLOGY, BIODIVERSITY AND ETHNOMEDICINE

Submitted to:

Social Inclusion Research Fund Secretariat

Apprenticeship Grant (SIRF/RF/07)

Submitted by:

Dil Kumar Hangsurung Limbu

April, 2008

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I acknowledge my thanks to Social Inclusion Research Fund Secretariat for providing

the research fund for this project.

My sincere thanks go to Dr. Laya Prasad Upreti, my supervisor, for the continuous

guidance and encouragement throughout the project work.

Thanks are also due to Narendra Kerung (Lecturer, Panchathar Multiple Campus),

Rabindra Tumbapo (President, Kirant Yakthung Chumlung), Asal Nembang

(Headmaster, Ithung High School), and Teaching staffs of Saraswati High School for

their active support in the field work.

I also extend my thanks to Mr. Basanta Kumar Rai, research assistant of this project,

for his untiring help.

Last but not the least; I am thankful to the healer duo Mr. Amritman Tumbapo and

Mr. Mahasher Nembang, and many other key informants for gladly agreeing to

cooperate in this project.

ABSTRACT

An exploratory survey of indigenous Limbu knowledge on ecology, biodiversity and

ethnomedicine was carried out between November 2007 and February 2008 taking

Chokmagu and Ranitar VDC of Panchthar district (East Nepal) as the representative

sites. The study revealed that Limbu people use over 200 plants (apart from common

cereals and garden vegetables) for a multiplicity of purposes. About 110 medicinal

plants are found in various degrees of abundance while some 119 plants (including

unavailable ones) are used against a wide range of illnesses, ranging anything from

common cold to fracture. Allowing overlapping of usages, about 59 plants are used

for food, 107 for fodder, 28 as wild foods, 28 for veterinary purpose, 38 for murcha

making, and 37 for religious purposes. Almost all the plants (96%) studied had Limbu

names, which implies that the natives had been in close association with these plants

from eons past. The sensory attributes of the botanicals are often related to the

treatment of a specific disease. Contrary to the assumption, the abundance of plants

did not show association with the frequency of use or knowledge about them. Five

plants (chamlayo, asaare phul, budhi okhana, tinpate, and galgale) could not be

identified scientifically. Limbu people of the study site were found to carry out

subsistence farming (based on integration of livestock and agriculture activities) in a

very sustainable manner (conservation tillage, mini dike construction, crop rotation,

relay cropping, farmyard- and green manuring, and integrated pest management).

Because of the topographical and microclimatic constraints, however, the VDCs still

suffer from staple grain deficit. They make up for the deficit, among other things, by

barter system, trade of value-added products, and employments (self-, wage-, and

foreign). There is scope for intensive farming to improve food security status. Limbu

people of the study sites cope with natural calamities (landslides and flashflood, fire,

etc.) by traditional methods; they also use prophylactic measures utilizing local

resources and indigenous ideas. They do not know much about the link between

environment and biodiversity but are contributing their bit to it in their own ways

(e.g., by establishing devithan, and raniban to protect segments of forests). Based

on interview, to the best of the natives knowledge, no significant deterioration of

environment and biodiversity has occurred, even after the introduction of monoculture

(e.g., tea and cardamom) in parts of the VDCs. Gradual dwindling of murcha plants,

however, is of concern. Based on accumulated data, the most common illnesses were

cuts/wounds, fracture, diarrhea, worms/helminthes, piles and jaundice. Fortunately,

they have adequate knowledge for carrying out the primary care of these illnesses by

traditional means. In particular, methods used by the local healers to treat fracture

appear intriguing enough to warrant further scientific investigations.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .........................................................................................i

ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................ii

CONTENTS................................................................................................................ iii

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES........................................................................... v

CHAPTER - I

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1

1.1 Background.......................................................................................................... 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem..................................................................................... 1

1.3 Objectives of the Study........................................................................................ 3

1.4 Rationale of the Study.......................................................................................... 3

CHAPTER - II

LITERATURE REVIEW........................................................................................... 5

2.1 Indigenous Knowledge and Its Scope.................................................................. 5

2.1.1. Indigenous People of Nepal ......................................................................... 7

2.1.2 Indigenous Knowledge of Nepal .................................................................. 8

2.2 Biodiversity and Its Scope ................................................................................... 9

2.2.1 Biodiversity in Nepal .................................................................................... 9

2.3 Traditional Ecological Knowledge .................................................................... 11

2.3.1 TEK and Scientific Ecological Knowledge ................................................ 11

2.3.2 Practical Significance of TEK .................................................................... 12

2.4 Traditional Medicines ........................................................................................ 13

2.4.1 Status of Medicinal Plants of Nepal............................................................ 14

CHAPTER - III

MATERIALS AND METHODS .............................................................................. 18

3.1 Rationale for Choosing the Research Site ......................................................... 18

3.2 Data Sources ...................................................................................................... 18

3.3 Sampling Frame................................................................................................. 18

3.4 Data Collection Techniques............................................................................... 19

3.5 Focus Group Discussion .................................................................................... 19

3.6 Case Studies....................................................................................................... 19

3.7 Data Analysis and Interpretation ....................................................................... 20

3.8 Limitations of the study ..................................................................................... 21

CHAPTER - IV

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION................................................................................ 22

4.1 Demographic and Related Details of the Study Site.......................................... 22

4.1.1 Chokmagu VDC.......................................................................................... 22

4.1.2 Ranitar VDC ............................................................................................... 22

iv

4.2 Focus Group Discussion .................................................................................... 23

4.2.1 Medicinal Plants of Chokmagu and Ranitar VDC...................................... 24

4.2.2 Interpretation............................................................................................... 36

4.3 Statistical Analysis............................................................................................. 51

4.4 Knowledgebase on Biodiversity and Ecology ................................................... 51

4.5 Use of Botanicals is Traditional Medicine......................................................... 55

4.5 Case Study ......................................................................................................... 65

4.5.1 Chokmagu VDC.......................................................................................... 65

4.5.2 Ranitar VDC ............................................................................................... 67

4.6 Interpretation...................................................................................................... 69

CHAPTER - V

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................ 71

REFERENCES........................................................................................................... 73

APPENDICES............................................................................................................ 80

v

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Tables

Table 4.1 Summary of response of the Focus Group on traditional uses of plants ..... 38

Table 4.2 Wild plants used for food purposes ............................................................. 44

Table 4.3 Plants used for veterinary purposes ............................................................. 45

Table 4.4 Plants used for religious purposes ............................................................... 46

Table 4.5 Plants used for murcha preparation ............................................................. 48

Table 4.6 Occurrence of illness term in the text. ......................................................... 65

Table A-I.1 Details of the key informants from Chokmagu VDC .............................. 80

Table A-I.2 Details of key informants from Ranitar VDC. ......................................... 81

Table A-II.1 Selected list of diseases taken for the interview..................................... 82

Figures

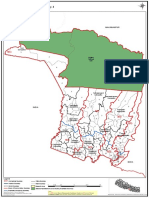

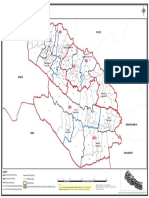

Fig. 3.1 Map of study site (shaded portion) ................................................................. 20

Fig. 4.1 Availability of medicinal plants in Chokmagu and Ranitar VDC.................. 50

Fig. 4.2 Intensity of the use of plants for medicinal purpose....................................... 50

Fig.A-I.1 Some key informants at Chokmagu VDC.................................................... 80

Fig.A-I.2 Some key informants at Ranitar VDC ......................................................... 81

Fig. A-III.1 Budhi okhana (used for fever treatment).................................................. 84

Fig. A-III.2 Aule gurans (used for treating bone fracture) .......................................... 84

Fig. A-III.3 Chimphing................................................................................................ 85

Fig. A-III.4 Herbarium of tinpate. ....................................................................... 85

Fig. A-IV.1 Sale of murcha cake in a local market ..................................................... 86

Fig. A-IV.2 Pakhanbhed on sale in a local market ...................................................... 86

Fig. A-IV.3 Hadchur on sale in a local market ............................................................ 87

Fig. A-IV.4 Research assistant engrossed in interview at Ranitar VDC..................... 87

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Nepal, a country with disproportionately rich cultural and ethnic diversity, is located

between the latitudes 26

o

22'-30

o

27' N and longitudes 80

o

40'-88

o

12' E. Its area,

147,181 km

2

, represents just 0.1% of the global land surface. Remarkably, however, it

claims over 2.04% of the worlds flowering plant-, 4.2% of mammal-, and 8.5% of

bird species. Due to altitudinal and climatic variations, there are almost all types of

climatic zones. There is a striking vertical zonation in natural vegetation and diversity

in flora, with 118 ecosystems, comprising 75 vegetation types, and 35 forest types

(MFSC, 2006).

The genetic resources of Nepal currently in demand can be classified within three

categories (Chongtenli and Sharma, 2006): (i) Agriculture and horticulture, (ii) Livestock

and fisheries, and (iii) Non-timber forest products (NTFPs). They are found in farms,

fields and forests. The use, propagation, and conservation of genetic resources are

based upon Nepals indigenous knowledge systems. Found in more than eight bio-

climatic zones, Nepals indigenous knowledge systems stretch across the country,

from the sultry tropical habitats of the Terai to the alpine and frigid habitats of the

high Himalaya.

There are 59 different ethnic groups, accounting for more than 43% of the kingdoms

population (Ukyab and Adhikari, 2001). These people, otherwise identified as

janajatis or nationalities, make up the lowest socio-economic and political strata.

They speak 75 different indigenous languages (Shrestha, 1997) and use over 800 plant

species for different purposes (Manandhar, 1997). They are known to employ diverse

traditional systems in environment management, agriculture, pastoral practices, and

health delivery. In fact, well above 80% of the population still rely on traditional

healing system for primary health care. The consultation and treatment provided

Government health services to the needy are barely about 10% and 3%, respectively

(Yakthung Chumlung, 2004).

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Today, indigenous knowledge (IK) is recognized as a critical factor for sustainable

development (Gorjestani, 2004) because local knowledge is not only the beliefs

transmitted from generation to generation, obtained as a result of experience but also a

dynamic resource modified by contemporary experience and experimentation.

Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity (which includes species-, genetic-, and

ecological diversity) are considered to be complementary phenomena essential to

human development (Warren, 1992). Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) has

already been successfully applied to management questions in different parts of the

world, such as Alaska, Australia, South America, etc. Ignoring indigenous knowledge

has had several disastrous consequences in the past (Hagen, 2000). This is why there

is a growing interest in TEK among the resource managers: they want to employ this

knowledge in creative management and restoration strategies. Therefore, it is not

surprising that a growing cadre of researchers is pursuing creative approaches to

2

recovering various aspects of TEK and vetting this knowledge scientifically (Striplen

and DeWeerdt, 2002).

Biodiversity is increasingly becoming recognized as important beyond its purely

scientific interest. Social and economic values of biodiversity are assuming greater

significance as a range of different groups, including indigenous peoples, assert their

claims and interests. Biodiversity provides diverse environment, which in turn

provides an important storehouse for the raw materials used in a range of products and

processes, such as in agriculture, medicine, and cosmetic. The pharmaceutical

industry is arguably the largest commercial user of plant genetic species, and the

development of these products can create significant opportunities for economic

growth for this industry sector (Davis, 1998). It is worthwhile noting that 25% of

prescription drugs are derived from plants, and that of these some 75% have been

developed with some input from traditional knowledge (Young, 2001).

The contribution of indigenous and local communities to the conservation and

sustainable use of biological diversity goes far beyond their role as natural resource

guardians. However, due to rapid modernization, many of the indigenous practices are

on the verge of extinction. The condition is going worse from bad in many countries

because IK has not been accorded the share of attention it so well deserves.

Today, interest in indigenous peoples knowledge and cultures is stronger than ever

and the exploitation of those cultures continues. Indigenous medicinal knowledge and

expertise in agricultural biodiversity and environmental management are used, but the

profits are rarely shared with indigenous peoples themselves. For indigenous peoples

all over the world the protection of their cultural and intellectual property has taken on

growing importance and urgency. They cannot exercise their fundamental human

rights as distinct nations, societies and peoples without the ability to control the

knowledge they have inherited from their ancestors.

The ethnic groups of Nepal have overwhelming representation in relation to

population (43% of kingdoms population), ethnic diversity (59 ethnic groups), and

indigenous knowledge systems. However, despite worldwide appreciation of

indigenous knowledge systems, there is paucity of researches on the same in Nepal.

A preliminary study on the knowledge of Limbus in Taplejung, Terhathum, Ilam,

Dhankuta, Sankhuwasabha and Panchthar (Yakthung Chumlung, 2004) districts

reveals that they use around 280 plants for medicinal purpose. Their healing practice

and folklore have been described to some extent but a holistic research on their

knowledge base as regards ecology, biodiversity conservation and ethnomedicine is

still scanty.

Limbus have been using hundreds of plants for the treatment of diseases (Siwakoti,

1998; Subba, 2006), ranging anything from diarrhea, constipation, to fracture.

Conservation and revival of this knowledge base is very crucial because traditional

medicines are still the most important primary healthcare sources for the vast majority

of the rural mass.

Most Limbus lead a rural life, normally adjacent to forests. Forest continues to play an

important part in their life. But these resources, and the complex system that ensure

their survival, are under threat. The greatest current threats are social, ecological,

economical, and political. Undervaluation of native crops and animals, lack of secure

land tenure, erosion and marginalization of traditional knowledge, inappropriate

agricultural policies, commercial extraction of non-timber forest products (NTFP),

3

etc., are some of the known threats facing these people. Despite the wealth of

traditional practices available in Nepal, unfortunately, no comprehensive data exist

vis--vis their inventory, contribution towards sustainable development, and the

magnitude of impact they have on our lives. At this point, since indigenous

knowledge is intimately associated with our identity (and even survival), any effort

expended on any of its aspects should be more than justified (Rai, et al., 2006).

As newer trends set in, Limbus fear that the body of knowledge they have might one

day be lost for ever. Earlier studies also show similar indications. It is therefore very

essential that a thorough documentation of their indigenous practices and the

implication(s) of these practices on sustainable development, their very own survival,

biodiversity and resource management, and enrichment of the culture be carried out

before it is too late

1.3 Objectives of the Study

The main objective of the study was to carry out an exhaustive documentation of the

knowledge base of Limbus and explore its relationship with biodiversity,

ethnomedicine and ecology.

This study concentrated on the following specific objectives:

a. to document and analyze indigenous knowledge system of eco-friendly

agricultural practice, and forest and landslide management;

b. to document and analyze indigenous knowledge of plants used for food (and

related use), pest management, and medicine;

c. to ascertain and explicate the effects of traditional practices on ecology,

environment and livelihood.

The study was based on following simple but fundamental questions:

1. What indigenous knowledge systems are being used by the inhabitant for

agricultural practice, natural resource management, and overcoming natural

calamities? And are they sustainable?

2. What is the knowledge base of plants used for food, fodder and medicine?

How is it being transmitted to the new generation? What is its contribution to

rural socio-economy?

3. What is the diversity of medicinal plants? Why are some plants more likely to

be medicinal than others? Do organoleptic and symptomatic properties of

plants relate to treatment of specific illness?

1.4 Rationale of the Study

Nepal is endowed with a bountiful of floral diversity. High altitude regions in

particular are rich in medicinal plants. It is conceivable that the sustainable use of this

common heritage has far-reaching practical implications. And because it is

increasingly becoming clear that indigenous knowledge base offers the most

sustainable way of managing these natural resources, many rightly believe that

indigenous knowledge may hold the key to future.

A greater awareness on the importance of IK is likely to help preserve the knowledge

base for the use and benefit of the local community. Governments and international

development agencies are now recognizing that local-level knowledge and

4

organizations provide the foundation for participatory approaches to development that

are both cost-effective and sustainable (Warren, 1992). Little wonder, then, a host of

international NGOs and funding agencies have focused on and supported the

development of databases. The World Bank itself maintains an online database that

can be searched using regional and thematic keywords. Other databases can be

accessed from websites maintained by the International Development and Research

Center (IDRC), Conservation International, and Consultative Group on International

Agricultural Research (CGIAR) among others (Agrawal, 2002).

As such, the objective of databases on indigenous knowledge is typically twofold.

First, they are intended to protect indigenous knowledge in the face of myriad

pressures that are undermining the conditions under which indigenous peoples and

knowledge thrive. Second, they aim to collect and analyze the available information,

and identify specific features that can be generalized and applied more widely in the

service of more effective development and environmental conservation (Agrawal,

2002).

The present study can be of immense academic and practical value in the sense that

researchers working on similar themes may use it as a reference. The field visits and

the concomitant interaction with the inhabitants will be helpful in bringing awareness

among them on the importance of indigenous knowledge they possess. The finding

will be helpful in reducing the social divide between the haves and have-nots by

documenting, promoting, encouraging, and disseminating the indigenous

innovativeness for the benefit of the community themselves. The data generated in the

study will also be useful in relevant policy making (e.g., policy on extraction of non-

timber forests, conservation of biodiversity, etc.) by concerned bodies and the

government at the local, regional and national level. In the long run the finding can be

useful in the protection of cultural and intellectual property.

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Indigenous Knowledge and Its Scope

The term indigenous is a generalized reference to the thousands of small scale

societies who have distinct languages, kinship systems, mythologies, ancestral

memories, and homelands (Grim, 2001). These different societies comprise more than

300 million people throughout the planet today (Kihwelo, 2005).

Indigenous knowledge (IK) has been defined in different ways by different experts

and organizations (Johnson, 1992; Warren, 1992; Lugeye, 1994; Brush and Stabinsky,

1996; Grenier, 1998; Mugabe, 1999; WIPO, 1999). According to Johnson (1992),

indigenous knowledge is a body of knowledge built by a group of people through

generations living in close contact with nature. It includes a system of classification, a

set of empirical observations about the local environment, and a system of self-

management that governs resource use. This definition associates indigenous

knowledge with environment rather than knowledge related to artworks, handicrafts

and other cultural works and expressions (which are considered as elements of

folklore).

IK permeates every aspect of rural life, be that agriculture, natural resource

management, biodiversity, environment, food security, disaster control, health

practices, or pest control, in a sustainable way (Oniango, et al., 2003). This is why

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), signed by more than 150 states, has made

a very authoritative provision for dealing with indigenous knowledge in its Article

8(j) (UNEP, 1997).

Today, indigenous knowledge has come to occupy a privileged position in discussions

about how development can best be brought about so that finally, it really is in the

interests of the poor and the marginalized (Agrawal, 2002). A central argument is that

sustainable development must be embedded in indigenous knowledge systems, and

ignorance of the systems will certainly lead to failure in development (Lin, 2007).

Weatherford (1994) argued that indigenous people may be the only people capable of

salvaging the modern civilization. As indigenous people have gradually lost their

cultural identities, we are actually losing indigenous knowledge, our connections to

the past, and jeopardizing our future. According to Semali and Kincheloe (1999),

indigenous knowledge reflects the dynamic way in which the residents of an area

have come to understand themselves in relation to their natural environment and how

they organize that folk knowledge of flora and fauna, cultural beliefs, and history to

enhance their lives.

The work of protecting and promoting indigenous knowledge, however, is

challenging. The following urgent issues need to be examined and evaluated. First, it

is important to conduct research on how people can preserve the natural environment

of the indigenous people, since indigenous knowledge and their natural habitats go

hand in hand. Second, whether the existing Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) system

can be applied or extended to indigenous knowledge remains highly controversial

(Marinova and Raven, 2006). In this regard, emphasis must be placed on the

development of Traditional Resource Rights (TRRs) which can protect the interests of

indigenous peoples and strengthen the practice of their self-determination

6

(Plenderleith, 2004). Third, a unique institutional system for the advancement of

indigenous knowledge needs to be developed (Lin, 2007).

International and national development agencies have recognized the value of

participatory approaches to decision-making for sustainable approaches to

development. During the past decade a rapidly growing set of evidences indicates a

strong relationship between indigenous knowledge and sustainable development.

Development agencies are beginning to review the role of indigenous knowledge in

the development process at the policy level (Warren, 1992). According to U.S.

National Research Council (1992), compilation and documentation of indigenous

knowledge should be a research priority of the highest order: and because indigenous

knowledge is being lost at an unprecedented rate, its preservation, preferably in

database form, must take place as quickly as possible.

Development activities that work with and through indigenous knowledge and

organizational structures have several important advantages over projects that operate

outside them. Indigenous knowledge provides the basis for grassroots decision-

making, much of which takes place at the community level through indigenous

organizations and associations where problems are identified and solutions to them

are determined. Solution-seeking behavior is based on indigenous creativity leading to

experimentation and innovations as well as the appraisal of knowledge and

technologies introduced from other societies (Warren, 1992).

In the recent years, a number of organizations, including the United Nations system,

have been active in promoting the rights of indigenous people. To date, there are some

37 indigenous knowledge resource centers worldwide established for preparing the

database on indigenous knowledge (Anon, 2001). This growing global network of

regional and national indigenous knowledge resource centers is involved in

documenting the historical and contemporary indigenous knowledge of numerous

ethnic groups around the world. Much of this knowledge is at as much risk of being

lost as is the case with biodiversity (Linden 1991). These centers reflect new values

that recognize indigenous knowledge as an important national resource. The centers

are establishing national indigenous knowledge databases, giving recognition to their

citizens for the knowledge they have created, providing a protective barrier for the

intellectual property rights of knowledge that could be exploited economically by the

country of discovery, and laying the foundation for development activities that build

on and strengthen the existing knowledge and organizational base produced through

many generations of creative effort by local communities (Warren, 1992).

Innovative technologies discovered and used in one part of the world can often work

equally well in similar ecozones in other parts of the world. National centers are in a

position to facilitate and control the sharing of indigenous knowledge. This type of

information exchange has already begun through multilateral and bilateral donor

efforts. Two examples are based on indigenous knowledge from South Asia. The

World Bank has disseminated information at the global level on the traditional use of

vetiver grass in India for soil and moisture conservation (Greenfield, 1989). The use

of neem (Azadirachta indica) tree seeds to produce non-toxic biopesticides has also

spread from India to other parts of the world through development agencies such as

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and German Agency for

Technical Cooperation (GTZ) (Radcliffe et al., 1992).

National indigenous knowledge resource centers are organizational structures through

which indigenous knowledge is recorded, stored, screened for potential economic uses

7

at the national level, and distributed to other centers in appropriate ways. These

centers can serve as vehicles to introduce indigenous knowledge components into the

formal curricula from primary school through the university as well as in extension

training institutes. This can help augment the declining capacity of the traditional

means of transmission of this knowledge due to universal primary education now

operating in most newly-independent nations (Ruddle, 1991; Ruddle and Chesterfield,

1977).

National indigenous knowledge resource centers are beginning to conduct inventories

of knowledge that can be of primary utility in development programs. Examples

include indigenous crop pest management systems, farmers perceptions of positive

and negative characteristics of crop varieties, and indigenous approaches to the

management of soil, water, and biodiversity resources. National centers can also

identify and delineate the structure and functions of indigenous organizations that

exist in every rural community. Virtually every grassroots organization plays a

developmental function within the community. Strengthening the capacity of these

existing organizations can greatly facilitate sustainable approaches to development

(Warren, 1992b; Atte, 1992).

2.1.1. Indigenous People of Nepal

With distinct language, religion, customs, folklore, culture, knowledge and ancient

territory, 59 ethnic groups of Nepal have now received the legal recognition as

indigenous people (otherwise identified as janajatis or nationalities). These groups

have been consolidated through Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities

(NEFIN), a national level organization constituted by the government, as the umbrella

organization (Sherpa, 2005). NEFIN has defined 10 of the 59 janajati groups as

endangered, 12 as highly marginalized, 20 as marginalized, 15 as

disadvantaged, and two as advantaged or better off.

Janajatis account for more than 43% of the kingdoms population (Ukyab and

Adhikari, 2001; NEFIN). These people make up the lowest socio-economic and

political strata. They speak 75 different indigenous languages (Shrestha, 1997).

Although janajatis are largely excluded from main streams of national policies they

are contributing own cultural wisdom on restoration, conservation, and wise use of

biodiversity, natural resources, and traditional knowledge associated with their life

from millennia (Sherpa, 2005).

Limbus are one of the major ethnic groups of Nepal (Siwakoti and Siwakoti, 1998).

According to census 2001, they represent 1.58% of the kingdoms population and are

concentrated mainly in Terhathum (40,041), Panchthar (81,408) and Taplejung

(56,324) districts, totaling 359,379 in population (CBS, 2003). The literacy rate of this

nationality is 58.12% (CBS, 2001). They have a very rich cultural, ethnobotanical,

and food heritage (Bista, 1967; Bairagi Kainla, 1996; Subba

1

, 1999; Subba

2

, 1999;

Sherma, 1999). Their scripture is called Mundhum. Phedangba, Shamba and Yeba-

Yema are their sacred specialists. These shamans are not only performers but also

healers. Limbus celebrate the dance festivals of Kelang popularly known Chyabrung

(two-sided drum) and Yarak (paddy dance) as major events. Limbus have their own

script called Sirijunga. There are many books written in the Limbu language. Apart

from their culture and folklore, their traditional knowledge on medicinal plants and

food has been described in general (Yakthung Chumlung, 2004; Rai et al., 2005).

8

Limbus have excellent traditional knowledge base (Rai et al., 2005) and extraordinary

innovativeness. They are worshippers of nature or animists (Subba

1

, 1999). Unlike in

most nationalities, problem of gender parity has never been observed in the Limbu

community. Their relationship with ecology, biodiversity and ethnomedicine merits

special mention because this is what has enabled them to survive the odds of the

hostile environment and sustain the fragile ecosystem. Unfortunately, work on this

specific area is still scanty.

2.1.2 Indigenous Knowledge of Nepal

Nepalese indigenous peoples residing in diverse physiographic zones with traditional

life styles are closely attached with ecosystem, biodiversity, natural resources, and

environment from millennia. Biodiversity and natural resources are valuable sources

for food/fodder, medicine, fiber, building materials, etc., for these people. The rich

cultural heritage of Nepal has evolved over the centuries. This multidimensional

cultural heritage encompasses within itself cultural diversities of various ethnic, tribal,

and social groups, located at different altitudes, and is also manifested in various other

forms, including music and dance; art and craft; folklores and folktales; languages and

literature; philosophy and religion; festivals and celebrations; and foods and drinks.

Sporadic attempts have been made by different organizations and individuals (both

within the country and abroad) at different times to document the traditional

knowledge base. The works range from customs, folklore, language, rituals,

technology, food/fodder, medicine, to management of natural resources. Given the

diversity of community and the ecology they survive in, it is conceivable that there

could well be many more traditional knowledge systems yet to be unearthed.

Nepal has been recently placing much emphasis on traditional knowledge and its

research, with its becoming party to CBD, in particular. Nepal signed the CBD

in1992. With ratification of articles from the Parliament in 1993, Nepal became the

party in 1994 in accordance with the provision of the Convention. The Ministry of

Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) serves as the national focal point to this

Convention. Nepal submitted the Third National Report to CBD in 2006. The report

reveals that Article 8(j) and related provisions has yet to be addressed at the

government level. The report further mentions that the country is facing difficulty in

registering biodiversity and associated traditional knowledge, skill, techniques,

innovations and practices due to limited financial and technical assistance.

Nevertheless, preparation of national registers on traditional knowledge is in the

priority list. An updated national register of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs)

has already been prepared in 2004 (MFSC, 2006).

In Nepal, IUCN has remained a major player in the promotion and research on

indigenous knowledge. However, as Dangol (2004) puts it, in working with the spirit

of CBD, we need assurance that our traditional knowledge will remain secured from

misappropriation by national and international authorities/ individuals/ agencies

before we decide to document it for the benefit of our present and future generations.

Without a doubt, traditional knowledge plays an important role in health, food

security and agriculture. It is often a catalytic force in the protection, conservation and

sustainable use of biodiversity and ecosystems. It can also provide a benchmark for

controlling biopiracy and future commercial use of plant and animal genetic

resources, an issue that is becoming critical as Nepal negotiates to enter the World

Trade Organization (WTO) (Banskota, 2004).

9

It is relieving to find that indigenous technologies are slowly finding their ways into

academic curricula. For instance, M. Tech. (Food) Degree of Tribhuvan University

has included Indigenous Foods of Nepal in its curriculum (CCT, 2002). Department

of Environmental Science of the Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science (IAAS)

has designed two courses: (i) Fundamentals of Ethnobiology offered to B.Sc.

Agriculture students majoring in Conservation Ecology, and (ii) Applied

Ethnobotany for M.Sc. Agriculture students majoring in Conservation Ecology

(Dangol, 2007).

2.2 Biodiversity and Its Scope

Biodiversity refers to the variety of all life forms - the different plants, animals and

microorganisms, the genes they contain, and the ecosystems of which they form a

part (Davis, 1998).

Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity are complementary phenomena essential to

human development. Today, the relationship of biodiversity with indigenous people is

gaining more importance than ever. Indigenous people are custodians and stewards of

their lands and environments. The traditional methods they use to manage the natural

resources have been considered very sustainable. It is conceivable, therefore,

traditional system of resource management holds key to the future.

Global awareness of the crisis concerning the conservation of biodiversity is assured

following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in

June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro. Of equal concern to many world citizens is the uncertain

status of the indigenous knowledge that reflects many generations of experience and

problem-solving by thousands of ethnic groups across the globe. Very little of this

knowledge has been recorded, yet it represents an immensely valuable database that

provides humankind with insights on how numerous communities have interacted

with their changing environment including its floral and faunal resources (Warren,

1992).

The importance of and global commitment towards the conservation of biodiversity is

no longer questioned. The accelerating rates of loss of floral and faunal species and

the projected negative impacts of this loss of germplasm on humankind have been

eloquently described by a growing number of prominent biological scientists.

Numerous international foundations, development agencies, and international

agricultural research centers are also adding the power of their collective concern and

resolve to deal with the circumstances leading to the loss of species. Their focus has

been on the immediate and long-term negative biological and economic consequences

of the loss of biodiversity. Some have introduced the complementary importance of

cultural diversity that is often reflected in the indigenous knowledge of natural

resource management including that of plants and animals (Warren, 1992).

2.2.1 Biodiversity in Nepal

Nepal is a sovereign country with just 0.1% of global land surface. Remarkably,

however, it claims over 2.04% of the worlds flowering plant-, 4.2% of mammal-, and

8.5% of bird species. It occupies 25th and 11th position on biodiversity in the World

and Asia respectively (Sherpa, 2005; MFSC, 2006).

Nepal is rich in cultural, biological and ecological diversities due to its diverse

physiographic zones, climatic contrasts and altitudinal variations, which in turn

provide habitats for biological species of both Indo-Malayan and Palaeoarctic realms,

10

including endemic Himalayan flora and fauna. It is reported that 118 types of

ecosystems comprising 75 vegetation types and 35 forest types have been identified

within the area. Nepal has over 167 species of mammals, 860 species of birds, 50

species of amphibians, 130 species of reptiles, and 7000 species of higher plants

(Barchacharya et al., 1988; Joshi and Joshi, 1991; Wikipedia, 2007; Shrestha, 1998).

Some of these appear in the list of critically endangered-, endangered-, near

threatened-, threatened-, and extinct species.

The flora of Nepal contains about 1000 economic plants (440 spp. wild foods, 71 spp.

fiber yielding, 50 spp. fish poison, 30 spp. wild spices, and over 100 spp. fodder-

yielding trees) (Bhattarai, 2003). About 100 species of medicinal and aromatic plants

(MAPs) are exploited for commercial purposes (Mall, et al., 1993).

Biodiversity possesses ecological, economic and societal values. Biodiversity and its

products are used in different occasions from the birth to the death in Nepal.

Biological resources and associated traditional knowledge play a vital role in the

livelihood of Nepalese society. It is linked with food security, human health, and

environment. Conceivably, Nepals biodiversity is the mainstay of the countrys

economy and the well-being of its people. Its protection and sustainable use therefore

remains a top priority. To this end, Nepal has given utmost importance for the

conservation of biodiversity with peoples willing participation within and outside

protected areas. Nepal has also promoted sustainable use of biodiversity and benefit

sharing through policy and legal instruments (MFSC, 2006).

Despite this fact, however, growing population, poverty, deforestation and habitat

loss, erosion of crop genetic diversity, etc., have always remained a challenge. In

order to best conserve and sustainably use Nepalese biodiversity for meeting the

national goal of poverty reduction, additional financial support is required for raising

awareness among stakeholders, institutional strengthening, capacity building,

technology transfer, and bioprospecting. Nepal has already initiated biodiversity

documentation program in collaboration with national non-governmental

organizations (MFSC, 2006).

The most objectively verifiable indicators to efforts expended towards biodiversity

conservation are the establishment of Protected Areas (19% of the total land mass),

and National Forests being handed over to communities in the form of Community

Forests (CF). During the fiscal years 2002/03 and 2003/04, the Ministry of Forests

and Soil Conservation (MFSC) through its institutional network formed over 1400

Community Forestry User Groups (CFUGs). These activities respect traditional use

and rights of local people relating to forest resources for their basic needs.

Participatory conservation programs have been expanded for better forest

management, social mobilization, income generation and institution building at the

grassroots level. In the recent years, Nepal has approached to use forest products as

one of the major resources for poverty reduction as well. Conservation of wild flora

and fauna has been taken care by shifting the species protection to sustainable

utilization and benefit-sharing regime (MFSC, 2006).

Peoples participation and empowerment is the key for natural resource management.

Biodiversity documentation has been started. Contribution of medicinal herbs and

non-timber forest products (NTFPs) has been greatly realized for poverty reduction

(MFSC, 2006).

11

2.3 Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) represents experience acquired over

thousands of years of direct human contact with the environment. Although the term

TEK came into widespread use in the 1980s, the practice of TEK is as old as ancient

hunter-gatherer cultures. In addition to ecology, the study of traditional knowledge is

valued in a number of fields. For example, in agriculture, pharmacology and botany

(ethnobotany), research into traditional knowledge has a rich history. In fact, in

comparison to these fields, the study of indigenous knowledge in ecology is relatively

recent (Freeman, 1989).

The earliest systematic studies of TEK were done by anthropologists. Today, there

has been growing recognition of the capabilities of ancient agriculturalists, water

engineers and architects. Increased appreciation of ethnoscience, ancient and

contemporary, paved the way for the acceptability of the validity of traditional

knowledge in a variety of fields. Ancient ways of knowing started to receive currency

in several disciplines, including ecology. Various works showed that many indigenous

groups in diverse geographical areas from the Arctic to the Amazon had their own

systems of managing resources. Thus, the feasibility of applying TEK to

contemporary resource management problems in various parts of the world was

gradually recognized.

Professionals in applied ecology and resource management fields such as fisheries,

wildlife and forestry have been slow to take up the challenge of TEK. The reasons for

this are as complex as they are perplexing (Freeman, 1989). With the recognition of

the value of TEK, the growth of the field has been rapid, however. It should be noted

though that most of these contributions have come from interdisciplinary scholars

rather than from ecology and resource management professionals.

There is no universally accepted definition of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)

in the literature. The term is, by necessity, ambiguous since the words traditional

and ecological knowledge are themselves ambiguous (Lasserre and Ruddle, 1982;

Ruddle and Johannes, 1989; Freeman and Carbyn, 1988). A working definition is as

follows (Inglis, 1993): TEK is a cumulative body of knowledge and beliefs, handed

down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living

beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment. Further, TEK

is an attribute of societies with historical continuity in resource use practices; by and

large, these are non-industrial or less technologically advanced societies, many of

them indigenous or tribal (Berkes, 1993).

2.3.1 TEK and Scientific Ecological Knowledge

There are both similarities and differences between traditional science and western

science because they both are the result of the same general intellectual process of

creating order out of disorder (Berkes, 1993). There are also major differences,

however, between the two kinds of science, some of them substantive and some

perceptual. Opinions differ, but there is a great deal of evidence that traditional people

do possess scientific curiosity, and that traditional knowledge does not merely

encompass matters of immediate practical interest. According to Berkes (1993), TEK

in general differs from scientific ecological knowledge in a number of substantive

ways: (i) TEK is mainly qualitative (as opposed to quantitative); (ii) TEK has an

intuitive component (as opposed to being purely rational); (iii) TEK is holistic (as

opposed to reductionist); (iv) In TEK, mind and matter are considered together (as

12

opposed to a separation of mind and matter); (v) TEK is moral (as opposed to

supposedly value-free); (vi) TEK is spiritual (as opposed to mechanistic); (vii) TEK is

based on empirical observations and accumulation of facts by trial-and-error (as

opposed to experimentation and systematic, deliberate accumulation of fact); (viii) TEK

is based on data generated by resource users themselves (as opposed to that by a

specialized cadre of researchers); (ix) TEK is based on diachronic data, i.e., long time-

series on information on one locality (as opposed to synchronic data, i.e., short time-

series over a large area).

In contrast to scientific ecology, TEK does not aim to control nature, and is not

primarily concerned with principles of general interest and applicability (i.e., theory).

TEK is limited in its capacity to verify predictions, and it is markedly slower than

scientific ecology in terms of the speed at which knowledge is accumulated. A major

way in which TEK may be further distinguished from scientific ecology concerns the

large social context of TEK. TEK is not merely a system of knowledge and practice; it

is an integrated system of knowledge, practice and beliefs (Berkes, 1993).

2.3.2 Practical Significance of TEK

It follows from these considerations that the preservation of TEK is important for

social and cultural reasons. For the group in question, TEK is a tangible aspect of a

way of life that may be considered valuable. For the rest of the world, there are also

tangible and practical reasons why TEK is so important, quite apart from the ethical

imperative of preserving cultural diversity. The following paragraphs are adapted

from the IUCN Program on Traditional Knowledge for Conservation (IUCN, 1986):

1. Traditional knowledge can be used for new biological and ecological insights.

New scientific knowledge can be derived from perceptive investigations of

traditional environmental knowledge systems.

2. Traditional knowledge can be used for resource management because much

traditional knowledge has proved to be relevant for contemporary natural

resource management.

3. Traditional knowledge can be used for protected areas and for conservation

education. Especially where the local community jointly manages such a

protected area, the use of traditional knowledge for conservation education is

likely to be very effective.

4. Traditional knowledge can be used in development planning by involving

local people. The use of traditional knowledge may benefit development

agencies in providing more realistic evaluations of environment, natural

resources and production systems.

5. Traditional knowledge can be used for environmental assessment. People who

are dependent on local resources for their livelihood are often able to assess

the true costs and benefits of development better than any evaluator coming

from the outside. Their time-tested, in-depth knowledge of the local area is, in

any case, an essential part of any impact assessment.

In addition to these practical uses for TEK, it is also significant, that a newfound

awareness of TEK in mainstream western society can enhance our appreciation of the

cultures that hold this knowledge.

In the past, western science alone provided biological and ecological insights, the

knowledge base for resource management, conservation, development planning, and

13

environmental assessment. At this stage of the development of TEK, it is possible to

say that indigenous peoples and the knowledge held by them do have something to

contribute to each of the above areas. But traditional knowledge is complementary to

western science, not a replacement for it (Knudtson and Suzuki, 1992).

However, just what TEK can contribute and how is yet to be operationalized. As well,

the question remains as to how scientific knowledge and TEK can be integrated - and

whether such integration is desirable in the first place. Rooted in different world

views and unequal in political power base, these two systems of knowledge are

certainly not easy to combine. Serious attempts at integration inevitably come up

against the question of power-sharing in decision-making (Knudtson and Suzuki,

1992).

2.4 Traditional Medicines

The comprehensiveness of the term traditional medicine and the wide range of

practices it encompasses make it difficult to define or describe, especially in a global

context (WHO, 1991).

Traditional medicine has a long history. It is the sum total of the knowledge, skills and

practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different

cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health, as well as in

the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illnesses.

The terms complementary / alternative / non-conventional medicine are used

interchangeably with traditional medicine in some countries (WHO, 2000).

The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy Paper 2002-2005 explains that traditional

medicine attracts the full spectrum of reactions, ranging from uncritical enthusiasm to

uninformed skepticism. Yet the use of traditional medicine remains widespread in

developing countries. In many parts of the world, policy-makers, health professionals

and the public are wrestling with the question about the safety, effectiveness, quality,

availability, preservation and further development of this type of health care.

Meanwhile, in many developed countries, complementary / traditional medicine is

becoming more and more popular.

Practices of traditional medicine vary greatly from country to country, and from

region to region, as they are influenced by factors such as culture, history, personal

attitudes and philosophy. In many cases, their theory and application are quite

different from those of conventional medicine. Long historical use of many practices

of traditional medicine, including experience passed on from generation to generation,

has demonstrated the safety and efficacy of traditional medicine. However, scientific

research is needed to provide additional evidence of its safety and efficacy. In

conducting research and evaluating traditional medicine, knowledge and experience

obtained through the long history of established practices should be respected (WHO,

2000).

Despite its existence and continued use over many centuries, and its popularity and

extensive use during the last decade, traditional medicine has not been officially

recognized in most countries. Consequently, education, training and research in this

area have not been accorded due attention and support. The quantity and quality of the

safety and efficacy data on traditional medicine are far from sufficient to meet the

criteria needed to support its use worldwide. The reasons for the lack of research data

are due not only to health care policies, but also to a lack of adequate or accepted

research methodology for evaluating traditional medicine. It should also be noted that

14

there are published and unpublished data on research in traditional medicine in

various countries, but further research in safety and efficacy should be promoted, and

the quality of the research should be improved (WHO, 2000).

The methodologies for research and evaluation of traditional medicine should be

based on the following basic principles: On the one hand, the methodologies should

guarantee the safety and efficacy of herbal medicines and traditional procedure-based

therapies. On the other hand, however, they should not become obstacles to the

application and development of traditional medicine. This complex issue has been a

concern for national health authorities and scientists in recent years (WHO, 2000).

The discussion of methodologies for research and evaluation of traditional medicine is

divided into two parts: (i) herbal medicines, and (ii) traditional procedure-based

therapies. However, successful treatment is often the consequence of both types of

treatments acting synergistically. Thus, the efficacy of traditional medicine has to be

evaluated in an integrated manner, taking into account both treatment types.

Consequently, efficacy assessment of traditional medicine may be quite different to

that of conventional medicine. As traditional medicine relies on a holistic approach,

conventional efficacy assessment measures may not be adequate (WHO, 2000).

National policies are the basis for defining the role of traditional and complementary/

alternative medicine in national health care programs, ensuring that the necessary

regulatory and legal mechanisms are created for promoting and maintaining good

practice; assuring authenticity, safety and efficacy of traditional and complementary/

alternative therapies; and providing equitable access to health care resources and

information about those resources (WHO, 2001).

Recently, traditional medicine has become more mainstream even in the industrialized

world. To this end, WHO has recommended integration of traditional healing into

primary health care, and throughout the world governments have begun to consider

whether and how these alternative medicines should be regulated by the state (Young,

2001). It has been estimated that some 80% of the worlds population rely on

traditional medicine for primary health care, either because it is cheaper and/or more

easily accessible, or because it is more culturally appropriate.

Because of the increasing importance of traditional medicine in primary health care,

nations all over the world are carrying out vigorous researches on medicinal plants

and animal parts. The basis of research is of course the traditional knowledge held by

the natives. The examination of folk knowledge and health practices allows a better

understanding of human interactions with their local environment, and aids in the

formulation of appropriate strategies for natural resource conservation. It is well

known that the ethnopharmacological information reported forms a basis for further

research to identify and isolate bioactive constituents that can be developed into drugs

for the management of a large number of diseases.

2.4.1 Status of Medicinal Plants of Nepal

The diversity of species in Nepalese flora offers great opportunities for the search of

medicinal substances, not yet described or discovered. Medicinal herbs could be

viewed as a significant source of income for rural communities. Increasing worldwide

demand for medicinal plants also invites the danger of over exploitation and

extinction of species. Therefore, the world community as the consumer and the

natural resource rich countries as the exploiter would both need information as their

management tools (MFSC, 2006).

15

Medicinal and aromatic plants occur in all the bioclimatic zones of Nepal. Some of

the reputed medicinal plants like Rauvolfia serpentina and Terminalia chebula occur

in the tropical zone (1000 m asl); Dioscorea deltoidea, Adhatoda vasica, and Swertia

chirayita in the sub-tropical zone (between 1000 and 2000 m asl); Aconitum ferox,

Cactyorhiza hatagirea, and Lycopodium clavatum in the temperate zone (2000-3000 m

asl); and Nardosctachys grandiflora, and Rhododendrom anthopogon in the sub-alpine

zone (3000-4000 m asl). The steppic dry desert biome in the trans-Himalaya is rich in

Ephedra gerardiana, Hippophae tibetica, Artemisia sp., and Allium sp.

Nepal has a record of over 700 species of medicinal plants. There is a store of still

unwritten and undocumented traditional knowledge on the use of plants for healing

purposes. Shakya and Malla (1985) have confirmed 510 species of medicinal plants,

the distribution in the tropical, subtropical, and sub-alpine zone being 340 spp, 225

spp., and 140 spp., respectively. Nepal has a recently prepared a registry of MAPs

(MFSC, 2006).

The MAPs (also called jadibuti) database of Nepal covers 1624 species of plants

found in wild state or cultivated or naturalized or imported belonging to 938 genera

and 218 families. These are known to be used as medicine in Nepal (Koirala, 2005).

Manandhar (2002) has given an excellent account of more than 1,500 plants of Nepal,

most of which have great importance in traditional medicine.

The use of medicinal herbs in Nepals traditional medical system dates back to at least

500 AD. In Nepal, traditional medicine, although low profile, has been an integral part

of the national health system. Parallel to the allopathic system, traditional medicine is

encouraged in all spheres because of its efficacy, availability, safety, and affordability

when compared to allopathic drugs (Khakurel, 1996).

As of now, about 80% of the populations of Nepal have to depend on the traditional

medicinal care system (HMG-N, 1998). The consultation and treatment provided

Government health services to the needy are barely about 10% and 3%, respectively

Yakthung Chumlung, 2004).

The important traditional health delivery systems of Nepal include ayurvedic,

homeopathic, ethnobotanical, amchi (Tibetan medicine or healing practice), and

spiritual approach. Belief on witchdoctors is also rife. Countrywide, there are around

400,000 traditional healers/practitioners (Koirala, 2005). Ayurvedic system is an

official system of medicine and has now been integrated with allopathic medicine.

Formal education in ayurveda started in 1928 and as of now, there are 9 educational

institutions and 33 ayurveda pharmaceuticals.

The export of MAPs and NTFPs has had significant contribution to the national

economy from very early times. Thus, use of NTFPs and trade are traditional

phenomena in Nepal and the rural poor in the hills since time immemorial have been

involved in collection of NTFPs for sale and household use.

Nepal Government made efforts to improve export of crude herbs as early as 1937.

However, an organized department was not visualized until 1960. The Department of

Medicinal Plants currently renamed as the Department of Plant Resources oriented

itself towards scientific validation and research of Nepalese medicinal plants.

The export of medicinal herbs from Nepal was limited to India and China until 1960.

Nepals trade diversification has promoted herbal trade to oversea countries. Data

from the Trade Promotion Center show that export quantities amounted to over 4000

MT during mid 70s but the trend declined sharply during the 80s (Malla, 1994).

16

However, the trend is on the increase again, reaching about 13,600 MT in the year

1992-93. The major bulk of trade is still with India, amounting to 99% (Malla et al.,

1995).

As of 90s, about 10,000-15,000 MT of crude medicinal plants were collected

annually and much of these were traded to foreign countries. This trade is an

important source of livelihood and cash income to rural people, and is estimated in the

order of US$ 10 million. In certain cases, NTFPs, including MAPs, provide 50% of a

familys (Edward, 1996).

In a recent publication, Rawat (2007) has mentioned that about 20,000 MT of MAPs

worth US$18-20 million are traded every year, and about 90% are harvested in

uncontrolled fashion. Considering the increasing value of medicinal and aromatic

plants, both in terms of primary health care and as a critical source of livelihoods and

income for the rural poor in the region, International Center for Integrated Mountain

Development (ICIMOD) with support from the Common Fund for Commodities

(CFC), The Netherlands, is implementing a four-year project entitled Medicinal

Plants and Herbs: Developing Sustainable Supply Chain and Enhancing Rural

Livelihoods in the Eastern Himalayas in three countries (Nepal, Bangladesh and

Bhutan), with India as the technical expertise provider. Medicinal and Aromatic

Plants Program in Asia (MAPPA), a program of funded by International Development

and Research Center (IDRC) and Ford foundation has also been in operation in Asia

since its initiation in 1994.

The forestry share of the GDP is estimated at 15% (HMG-N, 1989). The Nepal-India

trade in NTFPs represents 4% of the total contribution of the forestry to the national

economy.

The Biodiversity Program Unit of the Asian Network for Small Scale Bioresources

(ANSAB) has focused its activities on assisting communities and development

practitioners to sustainably utilize NTFPs while conserving the ecosystems. Currently

some 18 research projects on various aspects of development, management and

sustainable use of wild plant resources including medicinal and aromatic plants are

being undertaken in different parts of the country. Likewise, some 10 institutions have

been provided with various types of technical assistance to conduct study and to

promote conservation, management and local level value-addition on various NTFPs

including medicinal and aromatic plants.

In the Nepalese context, although considerable research activities are being carried

out by various organizations and individuals, a serious lack of specific information

and mechanism for dissemination of available information has been urgently

experienced. However, the recently initiated Nepal NTFP Network, assisted by

ANSAB, is a forum for individuals and institutions to obtain, study and compare

research findings, as well as to disseminate information for the advancement of

understanding of the importance of development and management of biological

diversity and the sustainable utilization of the benefits and result from wild plant

resources. At present some 400 NTFP - related researchers and research organizations

are directly attached with the network. To this end, the collaborative work by

ICIMOD and the Netherlands on medicinal plants, as also the research support by

MAPPA, can be of great significance. Contribution at the individual level is also

accruing, for instance, work done by Ghimire (1999), Shrestha et al. (2000), Ghimire

et al. (2000), Lama et al. (2001), Ghimire (2001), Ghimire et al. (2002), Aumeeruddy

et al. (2002), Ghimire et al. (2004), Aumeeruddy et al. (2004), Malla and Malla

17

(2004), Pant and Panta (2004), Rokaya and Ghimire (2004), Rai et al. (2004),

Shrestha and Ghimire (2004), Shrestha et al. (2004), Yakthung Chumlung (2004),

Ghimire et al. (2005a), Ghimire et al. (2005b), Koirala (2005), Kunwar et al (2006),

Acharya and Pokhrel, (2006), Bhattarai et al. (2006), Pandey (2006), Rajbhandari et

al. (2007).

From the foregoing review, it is clear that indigenous knowledge and biodiversity are

intertwined and often strengthen each other. However, with the introduction of

modern/commercial systems, the local communities are on the brink of being caught

between the dynamics of exclusion and process of acculturation. The remoteness of

the rural areas has deprived the Limbu inhabitants of the modern amenities like access

to education, health facilities, communication and transport. This in turn has been a

determinant factor in their being excluded from the privileged section of the

population. Development has no doubt taken place in some areas but not without cost,

viz., erosion of traditional knowledge, propensity towards inappropriate acculturation,

and transition to unsustainable practices such as overharvesting of non-timber forests

(mainly murcha plants and medicinal herbs).

CHAPTER III

MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Rationale for Choosing the Research Site

Panchthar has the densest population of Limbus. There are 41 VDCs situated at

different elevations. The selection of two VDCs, namely Chokmagu and Ranitar, for

the present study as the representative sites stems from following facts and

assumptions:

1. these VDCs are relatively easy to access (for the study);

2. the elevation of these VDCs ranges from about 700 m to 3000 m, thereby

making them excellent for the study of biodiversity;

3. these VDCs have very rich distribution of Limbu nationality (and therefore

their indigenous knowledge);

4. because of the recent introduction of cardamom and tea cultivation, it is

necessary to assess whether plant and animal diversity are at stake;

5. because these areas have easy access to roadhead, overharvesting of NTFPs

might be taking place; and

6. people of Panchthar say that these VDCs have some of finest traditional

healers.

3.2 Data Sources

The primary data were obtained on site through participant observation, semi-

structured interviews (Key Informant and Focus Group), and questionnaires.

The data included details of the interviewees and questionnaire-respondents;

physiographic details of the study site; floral species (photographs), their occurrence

and abundance; video clips; discursive data (from interview); and questionnaire

responses. The general topics of interviews and questionnaires pertained to

biodiversity, ethnomedicine, traditional knowledge, natural resources and their

management, management of natural calamities, perception of environmental

changes, and the like.

The secondary data were obtained from District Development Committee, different

literatures such as those from Central Bureau of Statistics, WHO, National Reports on

CBD, ANSAB, IUCN, and various national and international journals dealing with

ethnomedicine, biodiversity, traditional knowledge, and sustainable utilization of

natural resources.

Documents from District Development Committee were used for abstracting data on

population distribution, ethnoprofile, area of VDCs, and basic amenities like

communication, education, transportation, and health services.

3.3 Sampling Frame

Because Panchthar district contains 41 VDCs, a significant number of them not

readily accessible within the given time frame for a census survey, a sample survey

was worked out by taking only two VDCs, viz., Chokmagu and Ranitar. Also,

because of the time constraint as well as scope of our study, a purposive sampling of

19

wards was carried out by selecting at least 4-5 wards or amalgamation (Ward No. 2, 3,

4, 6/7, and 8 of Chokmagu VDC and 2, 4, 6, and 8 of Ranitar VDC) as the sub-

sample. The purposive sample was thought to be very pertinent in relation to the case

study on ethnomedicine, which entailed interviewing of most well-known traditional

healer. This decision for the selection of wards was taken after consultation with

knowledgeable persons such as VDC secretaries, school teachers, and local members

of Yakthung-Chumlung (an organization of Limbu nationality) of the VDC in

question and a baseline survey. The consultation was made more effective by

explaining to them the purpose and implications of our visit. Nevertheless, attempt

was made to include all the elevational extremes within the VDC to facilitate

collection of as much of detail on biodiversity, ecology, ethnomedicine and traditional

knowledge as possible. A redrawn (to scale) map of the study site is given in Fig. 3.1

(wards not shown).

3.4 Data Collection Techniques

From each VDC, 9-10 key informants were selected by consultation with

knowledgeable persons of the VDC and interviewed in issues related to

ethnomedicine (using a combination of semi-structured questionnaires and free-listing

technique). A checklist of pertinent questions asked in the interview and details of the

key informants are given in Appendix-I and II.

3.5 Focus Group Discussion

Focus group discussion was carried out on ecology and biodiversity, for which 25

knowledgeable participants (selected by consultation with senior citizens, local

authorities) were invited. The incidental joining by other persons to share the

information was not considered objectionable. A checklist of pertinent questions used

in the interviews is given in Appendix-II. Use of discursive method was thought

important in contextualizing the quantitative data. Utilizing this approach, questions

were asked to stimulate conversation. Our participation was limited to occasional

asking for clarification. Only when discussions ended or strayed to a topic clearly

unrelated to illness did we ask another of the topical questions. A palm-top PC

containing database of some 300 medicinal plants from earlier study was used during

the interview for quick referencing and cross-checking the vernacular names of the

plants the participants mentioned.

3.6 Case Studies

Two case studies on traditional healing were planned for both the VDCs (one case

study each), the topical questions for which are given in the Appendix-II.

The interviewees for the case study were chosen by free-listing technique. Five to six

local respondents were asked to name a few well-known traditional healers in the

VDC. The response data on the domain were ranked. A new respondent was taken

and the response data reranked. Addition of new respondent and calculation of the

new rank went on until the ranks remained relatively stable. This was taken to be

adequate agreement about the domain. The healer with the highest rank was thereafter

selected for the interview. Having completed the selection process, the interviewee

was personally approached (a day earlier to the interview date) with request for

cooperation.

20

Taplejung

Amarpur

Nagi

Tharpu

Oyam

Falaicha

Panchami

Suvang Ekteen

Memeng

Chyangthapu

Yanganam

Sidin

Prangbung

Lungrupa

Phidim

Ranigaun

Chilingdin

Yasok

Mangjabung

Sarangdanda

Aangna

Mauwa

Hangum

Aarubote Rabi

Kurumba

Limba

Olane

Ranitar

India

Ilam

Terhathum

Morang

Ilam