Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wheat Report

Uploaded by

Zaryan IjazCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wheat Report

Uploaded by

Zaryan IjazCopyright:

Available Formats

A bumper wheat crop!

Shouldnt we celebrate?

Wheat harvesting is round the corner. It has in

fact already started in southern parts of the

country. It is likely to be a bumper crop. The

production estimates show that country will

cross the 24 million ton mark. It may actually

produce an unprecedented and all time high 25

million ton. This will make us a self-sufficient

country in this vitally important food crop.

Shouldn't we celebrate this achievement? Policy

makers are confused; traders perplexed and

farmers worried. This is how the agriculture is,

in this overly globalized world where less means

more opportunities to earn and more can spell

disaster.

Pakistan has almost always remained wheat-

deficient. Both the acreage and the per acre yield

of wheat have never been enough to feed its

burgeoning population. Yield hovered around

400 kg per acre till 1967-68. The so-called green

revolution pushed it up. It now stands at 1160

kilogram, which is still less by the international

standards. The average yield in the neighboring

Indian Punjab is 1680 kg per acre. The area on

which wheat is cultivated in Pakistan has also

doubled over past 60 odd years, yet we walk the

tight rope.

Perhaps low yield is less a result of 'technological

backwardness' of our farmer than of lack of

incentive for growing this crop. Wheat is a food

security crop and farmers work against heavy

Punjab Lok Sujag, South Asia Partnership-Pak; FR 03/09; April 2009

Wheat economy heading for boom or bust?

Make or break season for millions of farmers

odds to secure enough for the family. They cannot

dare to co-opt it. But they do not also see any

incentive in going beyond this point in a big way.

Wheat trade is dominated by the government

which is the biggest buyer of the home

production and also enjoys the authority to set its

price. Farmers hardly ever find the wheat Support

Price attractive enough to invest more resources

into this crop and produce the surplus required to

feed the non-grower population of the country.

Overall production in recent years has swung

between 17 and 23 million ton. The government

of Pakistan is a frequent visitor of wheat selling

markets of the world. It fills the supply gap

through expensive imports and has been

lamented for offering far more to farmers of other

countries than it does to its own.

Wheat price in Pakistan has traditionally been

lower than the international prices. It is set on the

basis of calculations made by Agriculture Pricing

Commission that claims it considers in-put costs,

inflation rate etc. It however always falls below

the expectations of farmers and has remained

stagnant for years. It remained Rs 240 per 40 kg

for three consecutive years, 1997 to 99, and then

Rs 300 for next four years. It was in a way

reflective of the political importance of wheat

farmers in our economy.

International market on the other hand is more

influenced by the demand and supply

perceptions and the expert forecasts of future.

Commodity prices, including wheat, peaked to

unprecedented high levels during last year along

side the prices of petroleum products. This

weighed heavily against our governments

reliance on wheat imports to fill the demand-

supply gap. To spur home production it raised

the wheat Support Price by a hefty 52 percent. It

moved from Rs 425 per 40 kg in 2006-07 to Rs 625

in the next to Rs 950 for the current. The farmers

response obviously has been overwhelming and

they promised a bumper crop.

The international market however has pulled the

rug from under the government. The wheat prices

that rose hand in hand with petroleum have

tumbled down. US wheat (FOB, Gulf) was quoted

at $454 per ton in March 08. It now stands at $241

and is expected to go down further as harvesting

in South Asia starts. The government of

Pakistans announced price for purchase of local

wheat translates into over $300 per ton. This

makes it the unique year for the local price is

higher than the international price for the first

time ever. So who will buy wheat from Pakistani

farmers at the government price?

Why the private buyers will keep off?

Private buyers will most likely keep out at least

until it gets out of the government hands and the

price crashes. It does not make good business

sense to buy at higher rates when it is available at

much lower price just across the Gulf. The much

publicized smuggling to Afghanistan will also

stop automatically. In fact we could see reverse-

smuggling if the international prices fall further;

that is cheap international wheat bought for

Afghanistan may find its way to the silos of

government of Pakistan. Businessmen however

will be keenly watching the government

procurement drive and will wait for their chances

of breaking deals at good rates.

This leaves the government alone with the

onerous task of fulfilling its promise of buying

wheat at the announced price of Rs 950 per 40 kg.

The government has exhibited the will to oblige

but how much can it buy?

Punjab is not only the biggest producer of wheat

in the country; it is the only surplus producing

province. 8 in every 10 kilograms of wheat

produced in the country come from this province.

Punjab Food Department is the biggest wheat

buyer. It comes under the provincial government.

Pakistan Agricultural Storage and Supplies

Corporation (PASSCO) is the other big buyer.

This comes under the federal government.

The two departments set procurement targets

each year and fail to achieve them many times as

farmers prefer private buyers who offer premium

over Support Price. But this time as the private

F a r me r R e p o r t 0 3 / 0 9 2

Wh e a t e c o n o my h e a d i n g f o r b o o m o r b u s t ? 3

P

akistan has seldom been able to

meet its wheat demand. It has

been covering the supply gap

through import of heavily subsidized

wheat from mainly the USA. For

many years the US bartered its

surplus wheat against Pakistans

support in furthering its political and

military interests in the region. As

subsidies in the West started going

down in 1980s, the cheap import

option got weaker and the

government started attending to

home production.

Wheat production is on the rise yet it

is not a smooth upward curve.

Weather conditions do matter to an

extent, but what really causes the

line to climb up or slide down is the

incentive that the government offers

to the farmers.

Punjab dominates the countrys

wheat production with a hefty

share that varies from

76 to 81 percent.

buyers will abstain, it will be an advantage to win

a procurement promise from the government

buyers. The favor is likely to become the new

currency of political patronage. Punjab is already

divided into constituencies of the two main

political parties, one ruling at the federal level and

the other at the provincial and both refusing to

come to terms with each other. Juxtaposition of

political constituencies over the jurisdictions of

the two procurement authorities may level a new

battle ground for the two political heavy weights.

Aside from the politics, the government

departments do not have the capacity to pick the

entire tradable surplus of wheat. The Punjab Food

Department has set 3.5 million ton procurement

target, while media reports put the same for

Passco at 1.5 million ton. Rs 111 billion has been

earmarked for Punjab Food Department and Rs

40.5 billion for Passco. The amount is being

released by a consortium of banks.

The government planners consider only 30

percent of total production as the tradable

surplus. It is a rule of thumb that needs

verification. Even at this percentage the current

seasons bumper crop will produce a surplus that

will be much more than the procurement targets

of the government.

Who will buy this leftover? The private buyers

will make a hay day when a gasping government

will be sitting over its brimming silos.

Who will suffer most in a price crash?

Wheat is grown by all farmers irrespective of the

size of their farm. According to Agriculture

Censuses 2000, 8 in every 10 farming families of

the country dedicate a portion of land to wheat

cultivation. In Punjab nine, NWFP eight, Sindh

five and in Balochistan four in every 10 farmers

grow wheat. In Rabi season almost 6 in every 10

cultivated acres of the country come under wheat

cultivation. All the three provinces except Punjab

are wheat deficient.

According to the last census around 69 percent of

Punjab families live in rural area. Almost half of

these (53 percent) have some access to land. They

either own a farm or have rented one on different

terms. The rest are landless laborers or are

attached to services and other sectors.

Access to land within these around 4 million

owners and/or tenants is highly skewed. Average

access of more than half of these (56 percent) is

just 2.1 acres. From the point of view of wheat

production, the Punjab farmers can be divided

into four broad categories. Here are the details:

1: Very small farmers

Around a third of Punjab farmers own on an

average just 1.2 acres of land. They are more than

1.3 million in number and cover almost their

entire area (1.1 acres) with wheat in Rabi season.

Their share in total wheat production of the

country is just 7.4 percent. Their produce is hardly

F a r me r R e p o r t 0 3 / 0 9 4

Farmers have shown time and again that they

have the capacity to fulfill the countrys wheat

demand, all they need is a fair incentive.

Wh e a t e c o n o my h e a d i n g f o r b o o m o r b u s t ? 5

What do farmers earn from wheat?

Agriculture in Pakistan is not a business in the

modern commercial sense of the word as in put

costs, out put prices and cash flow statements

are not the sole determinants of its dynamics.

Agricultures relation with the lives and

aspirations of farmers is not one-dimensional. It

instead is a tangle of complimentary and

contrasting social, historical, political and

economic factors. It makes it quite difficult to

quantify what exactly farmers get out of one

crop. We have attempted here to decode the

business of growing wheat.

As a first step here are the cash aspects. A

farmer in Punjab working under average

conditions needs to invest the following

detailed money to cultivate wheat on one acre.

We worked on the two extremes, the best in

which the farmer owns its entire land, has his

own tube well, tractor and its implements and

on the worst where he rents a piece of land and

buys or hires every thing else.

Worst Best

Land rent 3,000 0

Land preparation 1,000 700

Seed and sowing 950 950

Pesticides 1,000 1,000

Fertilizer (1xDAP) 2,000 2,000

Fertilizer (2xurea) 1,400 1,400

Fertilizer (manure) 800 500

Canal water 60 60

Tube well water 3,000 1,500

Total cash in put 13,210 8,110

DAP fertilizer was in short supply for the

current season and was bought by many at Rs

3000 per bag. The prices have now come down.

We have included an average expense actually

incurred by the farmers.

There are two million small farmers in Punjab

that cultivate wheat on four acres each. For

these farmers total cash in put for the current

crop has been 32 to 53 thousand rupees.

Harvesting is the most labor-intensive process

for almost all the crops. Wheat harvesters are

paid in kind. They include the groups that cut

the plant and stack them at one place; thresh

the grains out through threshers; pack the

grains; clear the ground by sifting the grains

from dust etc. All of them collectively charge

around 7.5 maunds (40 kg) per acres.

Wheat growers have to pay in kind a number

of village based professionals like barber,

cobbler etc., for their year long services. Each

farmer family pays these saipees on average 9.5

maunds. The farmer also sets aside wheat

enough for the family and the seed for the next

crop before offering it for sale. Here are the

calculations for an average small farmer

growing wheat on four acres

Maunds (40 kg)

Average production 29

Total production 116

harvesters share 30

Saipees share 9.5

Home consumption 22

Seed 5

Total utilized 66.5

Tradable surplus 49.5

Cash balance for the 4 acre farmer

(in rupees) Worst Best

Total cash in put 52,840 32,440

Selling price of surplus

at official rate 47,025 47,025

Net cash income - 5,815 14,585

Net cash income

at last years rate - 20,665 -265

If the small farmer working under best

conditions is offered the official rate of Rs 950

per 40 kg, he will make around 15 thousand

rupees from this five month crop besides

saving enough for the family for a year and

securing services from village professionals.

Another saving is the wheat stalk that makes

good fodder for the family's herd for many

months.

enough for the family itself. In fact to ensure this

they have to harvest it themselves and avoid

hiring labor for any other field job as well. This

effectively means that they themselves consume

their entire production and generate no surplus

for trade.

2: Small farmers

A little more than half of Punjab farmers own

(and/or rent) 5.8 acres on average. These around

2 million farmers cultivate wheat on 4 acres of

their land. Their share in Punjabs total output is

47 percent. After saving enough for the family

consumption and seed, they pay a considerable

amount to groups of harvesters in kind and also

oblige the service providers of the village called

saipee. Since the small farmers form the biggest

farming group, they are able to contribute 41

percent in the province's entire tradable surplus of

wheat.

3: Medium farmers

These over five hundred thousand farmers of

Punjab have on an average access to 20.5 acres of

land and dedicate over half (11.8 acres) of this to

wheat. The second half is occupied by other Rabi

crops most of which are grown for cash. The

medium farmers produce 35.5 percent of the

provinces entire wheat. As they too save for

family and seed and pay for services in kind, their

share in tradable surplus of Punjab wheat stands

at 45 percent.

4: Big farmers

They are around 50 thousand in number and their

land holding size on average is 86 acres. They

cultivate wheat on less than half (45 percent) of it.

They produce ten percent of Punjabs wheat and

their share in tradable surplus, according to

estimates, is around 14 percent of the total

surplus.

The government experts calculate the overall

tradable surplus of wheat as 30 percent of total

production. We have serious reservations about it

and our estimates put the surplus at much higher

level. Even if the official rule of thumb is accepted

a bumper crop of 25 million ton will produce a

tradable surplus of 7.5 million ton. In Punjab the

collective procurement target of Punjab Food

Department and Passco falls short of the expected

tradable surplus. The departments will leave at

F a r me r R e p o r t 0 3 / 0 9 6

The overwhelming majority

of farmers has very limited

access to land. Their

decision to grow wheat is

not a commercial one.

They in fact look for

securing the supply of

staple food for the family

and fodder for their animals

and want to ensure that

they would continue to

receive services of the

village professional through

out the year. If the sale of

surplus enables them to re-

pay the cash in-puts of

wheat crop, they consider

themselves lucky.

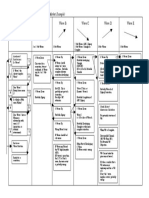

No of Average No of Average % share % share in

farms/ farm size farms as area under in total tradable

Punjab farmers families (acres) % of total wheat (acres) production surplus

Very small farmers 13,20,903 1.2 34.2 1.1 7.4 0

(less than 2.5 acres)

Small farmers 19,78,937 5.8 51.2 4.0 46.8 41.1

(2.5 to 12.5 acres)

Medium farmers 516,943 20.5 13.4 11.8 35.5 44.7

(12.5 to 50 acres)

Big farmers 47,285 85.7 1.2 38.6 10.3 14.3

(More than 50 acres) Source: Agriculture Census 2000; others

least a million ton with the farmers. The

government can in fact achieve its procurement

target by starting with buying the produce of big

farmers and ending with that of the medium

ones. Who will buy the surplus produced by the

small farmers? The private parties cannot be

expected to pay at par with the government in the

present international scenario. These two million

small farmers who have grown wheat on four

acres each, risk humiliation at the hands of

private buyers. And we are fast running out of

time. They grow almost half of the provinces

total wheat and a big loss in this year is bound to

negatively effect their contribution the next

season. According to careful estimates of cash

input costs of current season, a Punjab farmer on

an average has spent Rs 628 on the production of

40 kg wheat. This does not include land rent and

self-labor.

What can be done?

The political government had for the first time

ever dared to come face to face with the

international market by pricing its wheat at par.

The same however has up set the cart. We believe

the government needs to tackle the issue on two

fronts.

First and foremost it must act quickly to save its

small farmers from destruction. The government

departments are given purchase targets which are

then distributed among several of their purchase

centers. Performance of each is judged by what

percentage of target they have achieved. If we

have to save the small wheat farmer, we need to

ensure that the departments give priority to small

producers. As is evident from the data, the

smaller the farm size bigger is the share of wheat

cultivation. Very small farmers with average farm

size of 1.2 acres sow wheat on 88 percent of the

land available to them while big farmers with

average access to 86 acres, cultivate wheat on less

than half (45 percent) of their land. This implies

that the big and medium farmers grow other

crops in the same season as well and are more

able to sustain pressures on wheat. While for the

small farmers this crop is a make or break matter.

Moreover, small farmers with little clout are more

vulnerable to maneuvering by private traders. Big

farmers have storage facilities as well and they are

not pushed to sell their produce then and there.

They can wait for the market to turn in their

favor. Many times hoarding by big farmers has

caused the government difficulties in achieving its

procurement targets. On the other hand cash

strapped small farmers have to sell their produce

immediately after harvesting to keep their limited

cash flow cycle in tact. The government must

ensure that small farmers are preferred by its

departments in their procurement drive. It has to

go beyond political rhetoric and develop a

foolproof system. A crisis will be a big

disappointment for farmers that will definitely

reduce production in the coming season.

Wh e a t e c o n o my h e a d i n g f o r b o o m o r b u s t ? 7

Harvesting is labor intensive and labor is paid in

kind. It is the yearly opportunity for the landless

and menial workers to secure their food.

Secondly, the government needs to work with

other governments of developing countries to

look into the matters of international trade. Its

high volatility is a cause of big concern for our

small farmers. The temperamental global

commodity market should not be taken as a

natural phenomenon. The governments of

countries producing surplus for export unduly

shield their farmers from the effects of market

fluctuations. They ensure that their farmers get

reasonable returns whatever the way market

goes. This in fact encourages the market to waiver

wildly as the risks of the primary producers are

already effectively covered by their governments.

The governments need to effectively campaign

against these policies of exporting countries to

develop a rational global market.

To discourage opportunistic traders from spoiling

the announced procurement rate, the government

shall levy duty on cheap wheat imports till at

least the next harvesting season. It should ensure

that the international wheat is not available in the

country at cheaper than local wheat. This step will

deprive the local traders the option of cheap

imports and they might start buying local wheat

at the government announced price. The

government will have to be vigilant about the

smuggling of wheat into Pakistan as well.

Flat 8, RB 1, Awami Complex,

Garden Town, Lahore

Ph: 42 588 6454; 594 0166; 594 0206

South Asia Partnership-Pakistan

Haseeb Memorial Trust Building; Nasirabad; 2 km Raiwind Road, Lahore

Ph: 42 531 1701-6; Fax: 42 531 1710

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Earl The Complete Volume Spread Analysis System ExplainedDocument7 pagesEarl The Complete Volume Spread Analysis System ExplainedSardar Amrik Singh MallNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- AP Microeconomics TestDocument13 pagesAP Microeconomics TestGriffin Greco100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Asimov's New Guide To Science, 1993, Isaac Asimov, 0140172130, 9780140172133, Penguin Books, Limited, 1993Document16 pagesAsimov's New Guide To Science, 1993, Isaac Asimov, 0140172130, 9780140172133, Penguin Books, Limited, 1993Zaryan Ijaz33% (3)

- Technical Analysis: Dr. S. Sreenivasa Murthy Associate Professor Institute of Public EnterpriseDocument29 pagesTechnical Analysis: Dr. S. Sreenivasa Murthy Associate Professor Institute of Public Enterpriseramunagati100% (1)

- (Trading) Carolyn Boroden 'S S&P and NASDAQ Price Action Levels Reports PDFDocument12 pages(Trading) Carolyn Boroden 'S S&P and NASDAQ Price Action Levels Reports PDFnelson100% (1)

- How To Use MACDDocument6 pagesHow To Use MACDIstiaque AhmedNo ratings yet

- Donchian's 20 Trading GuidesDocument2 pagesDonchian's 20 Trading GuidesXhayneXeroath67% (3)

- Toms Vsa PrinciplesDocument4 pagesToms Vsa Principlesharishgarud100% (1)

- G7 Forex SystemDocument49 pagesG7 Forex SystemSun Karno100% (1)

- The Logical Trader PDFDocument137 pagesThe Logical Trader PDFprabath_tooNo ratings yet

- WB 1890 Back To Basics Trading SetupsDocument73 pagesWB 1890 Back To Basics Trading Setupsjanos_torok_4100% (1)

- Corrective WaveDocument1 pageCorrective WaveMoses ArgNo ratings yet

- Acetrades EbookDocument20 pagesAcetrades Ebookallegre50% (2)

- CFD Trading Strategies Using Market Index David James NormanDocument31 pagesCFD Trading Strategies Using Market Index David James NormanRehanNo ratings yet

- Question 1 and 2Document3 pagesQuestion 1 and 2Chetan Chopra0% (1)

- Admittance CardDocument1 pageAdmittance CardZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- List of Figures and TablesDocument2 pagesList of Figures and TablesZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- UET Taxila - PMLaptop Scheme - Phase2 PDFDocument31 pagesUET Taxila - PMLaptop Scheme - Phase2 PDFZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- MITOCW - MITRES2 - 002s10linear - Lec07 - 300k-mp4: ProfessorDocument17 pagesMITOCW - MITRES2 - 002s10linear - Lec07 - 300k-mp4: ProfessorZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- CZM For Instability Help - PdfaaDocument1 pageCZM For Instability Help - PdfaaZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- ISE 313 Computer Integrated Manufacturing and Automation I: Dr. Arslan M. ÖRNEK Industrial Systems EngineeringDocument7 pagesISE 313 Computer Integrated Manufacturing and Automation I: Dr. Arslan M. ÖRNEK Industrial Systems EngineeringZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- MS - Mechanical Engineering MS - Design and Manufacturing Engineering MS - Robotics & Intelligent Machine Engg MS - Biomedical Engineering/SciencesDocument1 pageMS - Mechanical Engineering MS - Design and Manufacturing Engineering MS - Robotics & Intelligent Machine Engg MS - Biomedical Engineering/SciencesZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- Stress Intensity Factor Fatigue Materials Science Fracture MechanicsDocument1 pageStress Intensity Factor Fatigue Materials Science Fracture MechanicsZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- NUST School of Mechanical & Manufacturing Engineering (SMME) Time Table - Spring 2016 Semester (01st Feb To 3rd June, 2016)Document1 pageNUST School of Mechanical & Manufacturing Engineering (SMME) Time Table - Spring 2016 Semester (01st Feb To 3rd June, 2016)Zaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- How To InstallDocument3 pagesHow To InstallZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Fretting Fatigue Crack Initiation in A Riveted Two Aluminum SpecimenDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Fretting Fatigue Crack Initiation in A Riveted Two Aluminum SpecimenZaryan IjazNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Gann - Square of 9Document5 pagesAn Introduction To Gann - Square of 9Mariam AliNo ratings yet

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument36 pagesMonopolistic CompetitionAmlan SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Report On FciDocument93 pagesReport On FciAlok VermaNo ratings yet

- Sana Nabi Kirti Siddapur Mandanna TM Rohan Nair Sudipta SarDocument27 pagesSana Nabi Kirti Siddapur Mandanna TM Rohan Nair Sudipta SarssarNo ratings yet

- Juan and The Inflation RateDocument2 pagesJuan and The Inflation RateMaster ReidNo ratings yet

- Gold Prices in IndiaDocument7 pagesGold Prices in IndiatechcaresystemNo ratings yet

- Preconditions For A Commodity Exchange, A Comparison Between ACE and ZAMACEDocument8 pagesPreconditions For A Commodity Exchange, A Comparison Between ACE and ZAMACEjohnnilNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument8 pagesReportAshwin MandowaraNo ratings yet

- Currency Market Weekly ReportDocument5 pagesCurrency Market Weekly ReportRahul SolankiNo ratings yet

- 01-A Color-Based System For Short-Term Trading PDFDocument4 pages01-A Color-Based System For Short-Term Trading PDFNathan ChrisNo ratings yet

- Stock Trak AssignmentDocument4 pagesStock Trak AssignmentPat ParisiNo ratings yet

- Line Way BillDocument2 pagesLine Way Billamekheimar1975No ratings yet

- Wetrewqrt PDFDocument33 pagesWetrewqrt PDFmikeraulNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of Demand PDFDocument35 pagesElasticity of Demand PDFSona Chalasani100% (2)

- Trading Course DetailsDocument7 pagesTrading Course DetailskinjalinNo ratings yet