Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FDI in India

Uploaded by

Vikram PatilCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FDI in India

Uploaded by

Vikram PatilCopyright:

Available Formats

NOTES

january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 66

FDI in India

Ideas, Interests and Institutional Changes

Sojin Shin

I appreciate Rahul Mukherji, my mentor, for

his support and all my interviewees for sharing

their insight during my eldwork. I also thank

National University of Singapore and TJ Park

Foundation (POSCO Asia Fellowship) for their

research funding.

Sojin Shin (sojin@nus.edu.sg) is a PhD

candidate in South Asian Studies at the

National University of Singapore.

This article examines the pattern

of foreign direct investment

inows in India through three

periods: (1) 1969-75, when the

policy regime was anti-FDI,

(2) 1975-91, when promotion of

FDI was selective, and (3) after

1991, when the policy regime

is pro-FDI. It shows how the

ideas and interests of different

political groups have affected

the institutional changes that

have inuenced FDI inows. It

also suggests that competition

between provincial states has

positively contributed to the

growth of FDI inows since the

economic reforms of 1991.

H

ow do political factors explain the

pattern of foreign direct invest-

ment (FDI) inows in Indian

industry that have shown a steady increase

since the economic reforms of 1991?

Although many students of Indias politi-

cal economy have examined the economic

reforms of 1991 in India, the extensive

literature has overlooked discussion on

foreign capital inows.

1

Some scholars

have partially explored this area (Kohli

1989; Mooij 2005; Tendulkar and Bha-

vani 2007; Panagariya 2008; Mukherji

2009); their interests however have

focused more on the overall transition of

economic reforms and the growth of FDI

inows rather than attention to the

institutional changes inuencing FDI

inows. This article is an attempt to ll

some of the gaps in the challenging

area. For this study, I conducted intensive

eldwork from December 2011 to March

2012. I interviewed some key political

leaders, bureaucrats and industrialists

in India during this period.

Following the historical institutionalist

perspective that emphasises the political

context interacting with economic insti-

tutional change, this article explains the

pattern of FDI inows at the union level.

The political factors addressed here are

competing ideas between foreign capital

supporters and their opponents and con-

icting interests among different indi-

viduals or different groups that have dif-

ferent political and economic interests.

In this regard, I would like to emphasise

competition that has had a signicant role

in producing the pattern of FDI inows in

India. This factor will help us to better

understand the steady rise of FDI inows,

especi ally in the post-reform period after

1991. It will also lead us to realise the

sub- national diversity of capacity among

states in India in attracting FDI inows.

Focusing on these three political factors,

this article will examine the pattern of FDI

inows in India that has gradually

evolved from the period of anti-FDI

inows (1969-75) to selective FDI inows

(1975-91), and nally to pro-FDI inows

(after the economic reforms of 1991).

Anti-FDI Inows, 1969-75

It was during Indira Gandhis leadership

from January 1966 to March 1977 that

foreign private capital was approached

with a more rigorous perspective than in

any other regime. Some institutions were

structured to efciently regulate nan cial

resources, including foreign capital.

Domestic banks were nationa lised in 1969,

the Quantitative Restrictions (QRs) were

strengthened, and the Foreign Exchange

Regulation Act (FERA) (1973) came into

being (Tendulkar and Bhavani 2007).

Such institutional arrangements were

the consequence of the political struggles

of Indira Gandhi against her political

opponents called the Syndicate.

2

A series of political and economic crises

that occurred in this period encouraged

Indira Gandhi to pursue socialist goals.

First, economic instability was obser ved in

the area of foreign aid. The US suspended

its nancial aid to India (and to Pakistan)

in 1965, when the India-Pakistan war

occurred (Frank 2001: 296). In the process

of industrialisation, policymakers empha-

sised the import-substitution industrialisa-

tion (ISI) stra tegy based on heavy industry

for Indias economic development during

this period. At this nascent stage of indus-

trialisation, nancial aid from abroad,

espe cially from the US and international

organisations such as the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank

(WB) was crucial, as it was difcult for

India to mobilise nancial resources from

domestic private capital that was not yet

competitive in the global market. The dif-

culties of nancial aid from abroad thus

meant a heavy blow to Indias economy at

that time (Frankel 2005 (1978): 322-26).

With the pressure of international

organisations, the US forced Indira

Gandhis government to devalue the rupee.

When liberalisation and devaluation

policies were implemented, the left-wing

political parties like the Communist Party

NOTES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 67

of India (Marxist) CPI(M) and domestic

private capital strongly oppo sed them.

Opposition from these groups was nomi-

nally based on the idea of swadeshi, but

it was mainly because of their interests

conicting with liberalisation and foreign

capital inows to Indian industry. Espe-

cially, domestic business groups that

were supporting the ISI strategy strongly

opposed devaluation because they had to

buy expensive imports. Opposing devalua-

tion and ination, trade unions organised

bandhs (strikes) in many provincial states

inclu ding West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha,

Kerala, Uttar Pradesh and some others

(ibid).

As a consequence of these bandhs

and continuous political instability, the

Congress Party lost 95 seats in many states

in the fourth general election in Febru-

ary 1967 (Frank 2001: 304). Even though it

could remain in power after the election,

a factional strife within the party intensi-

ed through the party split in 1969.

In such unstable political and eco-

nomic conditions, Indira Gandhis leader-

ship embarked on the nationalisation of

domestic banks in 1969. This bank nation-

alisation aimed at solidifying her political

support from the poor and the left-wing

parties. The political story behind Indira

Gandhis decision is well-described by

I G Patel, who was very close to her and

served as the governor of the Reserve Bank

of India (RBI), in his autobiography (Patel

2002: 135-38). At that time, the newly esta-

blished Banking Department under the

Ministry of Finance (MOF) was entrusted

with the task of management of the nation-

alised banks. Indira Gandhi used the new

presence of the government body as a

means of securing her political support

from the poor. Bank nationalisation was

to be a way to easily manipulate banking

resources in hard times and food scarcity.

Patel also acknowledges the inuence of

political struggle between Indira Gandhi

and her opponents on economic policy

decisions when he states: It is remarkable

how momentous decisions are made in

the heat of political struggle (ibid).

Poor harvests and droughts later

brought food scarcity threatening Indira

Gandhis leadership. External factors

like oil shocks in 1973 and 1974, in addi-

tion, negatively affected Indias economy

by depressing agricultural production

and generating ination (Ahluwalia

1986). Corruption was pervasive among

politicians and bureaucrats, at both the

centre and the states (Kochanek 1987:

1290). Political instability peaked in 1975

when the Allahabad High Court charged

Indira Gandhi with electoral corruption.

Foreign Exchange Regulation

Like bank nationalisation, the enactment

of FERA was also a by-product of her

political struggle, because she had to

enforce discipline by pushing her socia list

goals. The FERA was introduced in line

with the Industries (Development and

Regulation) Act (IDRA) that was enacted

in 1951 for regulating industrial invest-

ments and production. The key point of

this Act was that the centre had a critical

and monopolistic role in activities invol-

ving foreign currency. For example, no

one or none of the state agencies could

participate in any activities regarding

foreign currency, except the RBI, which

was designated as the only authorised

dealer by the centre. It restricted foreign

equity shares in Indian companies to no

more than 40% in domestic companies

under the strict monitoring of the RBI. In

addition, the FERA was in favour of

domestic companies when they bargained

with foreign companies. The enactment of

FERA enhanced the formers bargaining

position because competition among the

multinational corporations (MNCs) for

accessing the Indian market escalated

thr ough the FERA (Encarnation 1989: 118).

The enactment of FERA struck a blow

to domestic private capital as well as

foreign capital. Many companies retain-

ing their foreign share of equity more

than 40% were discriminated against

under the FERA scheme. These compa-

nies had to either reduce the foreign

share to 40% or less, or sell the foreign

promoters shares to Indian industrialists.

This discrimination continued until the

economic refo rms of 1991. Because of

FERA and some other radical measures

that strongly controlled domestic industry,

India under Indira Gandhis leadership

was indeed the most comprehensively

regulated market economy in the world

(Tendulkar and Bhavani 2007: 23).

Likewise, in the area of foreign colla-

boration and its related rules, care

[had] to be taken to ensure that foreign

collaboration is resorted to only for

meeting a critical gap and does not inhi-

bit the maximum utilisation of domestic

know-how and services.

3

As the Fourth

Five-Year Plan puts it:

It [was] necessary to subject every proposal

for foreign collaboration to fairly rigid tests;

even [import of foreign know-how particu-

larly in sophisticated industrial elds], it

would be essential to make simultaneous

efforts for the adaptation of such know-how

through indigenous effort and to improve on

it to avoid the need for future purchase.

4

In order to identify such elds where

foreign collaboration is needed and to

streamline the procedure for acceptance,

the Foreign Investment Board (FIB) was

set up. Unlike todays Foreign Investment

Promotion Board (FIPB) in the MOF that

promotes foreign investment, nonetheless,

the roles of FIB under Indira Gandhis

leadership addressed the control and

regulation of foreign investment.

Selective FDI Inows, 1975-91

Indira Gandhi attempted to neutralise

political and economic threats from her

opponents through the Internal Emer-

gency of 1975. Her leadership

sought to open up channels to key sections of

society notably the middle classes and middle

peasants to enhance cooperation and col-

laboration with the state, as well as to ensure

a more efcient form of resource extraction

(Hewitt 2008: 128).

The Emergency functioned as a means of

centralising and personalising her power

by transforming economic management.

Through the streamlining of industrial

licensing and emphasis on bureaucratic

efciency, the public sector could utilise

its capacity and achieve an increase of

output. In 1976, industrial output grew

by 10% over the total of 1975 (ibid: 129).

Nayar (2006) also observes the economic

transition that occurred in 1975. He argues

that the year 1975 was the initiation of

incipient liberalisation in Indias economy

and the end of the Hindu rate of growth.

The economic transformation towards

liberalisation was affected by intolerable

ination and difculties of obtaining

loans from the IMF.

Deregulation in the private sector sig-

nicantly contributed to further growth

in Indias economy.

NOTES

january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 68

The economic transition of 1975 also

inuenced the area of foreign investment

in Indian industry. Hewitt (2008) observes

that the Emergency was in fact used to

encourage foreign capital to participate in

Indian industry alth ough its original aims

addressed socialist goals (p 130). By enco-

uraging such participation, Indira Gandhis

leadership promoted production in the

public sector which was unproductive.

Frank (1977) also sees the change of econo-

mic orientation around 1976. As he put it:

(T)he state is being reorganised to serve the

interests of big and foreign capital more ef-

ciently and, relative to other economic sectors

and political interests, more exclusively (p 473).

Why did Indira Gandhis leadership

shift the economic strategies from con-

trolling both domestic and foreign capital

towards dismantling industrial regulations

and promoting the participation of foreign

capital in domestic industry? The strate-

gies seemed the easiest option for it to

mobilise business groups in order to

centralise its power and harness wider

societal collaboration. The business gro ups

welcomed the attempts at deregulation.

Indira Gandhi however failed to mobilise

the poor (who were her initial support

base) successfully after the party split;

she thereby struggled to reproduce cad-

res who could assist her within the rul-

ing party (Hewitt 2008: 131).

Deregulation and encouragement of the

participation of foreign capital in Indian

industry contributed to the increase of the

foreign exchange reserves. They gradually

grew after 1975 and exceeded $11,000

million in 1979 and 1980. The foreign

exchange reserves increased steadily dur-

ing the tenure of the Janata Party govern-

ment that came to power in March 1977.

Interestingly, this did not result from the

benign perspective of policymakers in the

government on the participation of foreign

capital in domestic industry. Morarji

Desai had taken over the prime minister-

ship from Indira Gandhi and H M Patel

became the nance minister. The govern-

ment did not use the handy foreign

exchange reserves even though the

economy recovered on the growth and

ination fronts (Joshi and Little 1991). In

fact, the previous chronic shortage of

foreign exchange strongly affected policy-

makers in the Janata Party government

who adopted a hoarding mentality with

respect to the foreign exchange reserves

(Tendulkar and Bhavani 2007), contrary

to the attitude of policymakers in the east

Asian countries, for example, South Korea.

The Janata governments under Morarji

Desais leadership and then Charan Singhs

leadership attempted structural trans-

formation in the industrial sector, but not

with respect to foreign investment in

that sector. The industrial policy changes

were designed for the partici pation of

non-resident Indians (NRIs) and domes-

tic private capital in Indian industry but

not for foreign capital. Interestingly,

even though key policymakers in the

Ministry of Commerce at that time con-

sidered foreign technology acquisitions

important, they did not pursue any scheme

for promoting foreign investment through

which domestic companies could easily

access advanced technology. The ideo-

logical orientation of the Janata Party in

favour of a self-reliant economy seems to

have inuenced the changes. Besides, the

nationalist wave affected some of the US-

based MNCs such as the Coca-Cola Com-

pany which pulled out of India in 1977.

When Indira Gandhi returned as prime

minister in 1980, industrial deregulation

accelerated. For business groups, the

Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices

(MRTP) Act was removed and entry barriers

to the Indian market were reduced. With

an attempt at deregulation, the government

led by Indira Gandhi simplied licensing

procedures. Nonetheless, there were two

limitations in this reform attempt. First,

her perspective on foreign capital did not

change much while she supported the par-

ticipation of domestic private capital in

industry. Second, despite the considerable

streamlining of licensing procedures in

industry, further improvement was nee ded

in reducing the period of time taken for

disposal of applications for the creation of

new capacities, proposals for substantial

expansion, and the production of new

items (GOI 1980). After all, the attempt

at economic reforms under Indira Gandhis

leadership was unsuccessful (Kohli 1989).

Under the Pressure of Crisis

The failure of reforms in promoting the

private sector under Indira Gandhis

leadership, external pressures from the

oil price rise, and the world recession in

the early 1980s again entailed commercial

borrowing rather than foreign investment

(Joshi and Little 1991: 58-62; Ganguly and

Mukherji 2011). Under the pressure of

crises, a benign idea on foreign investment

in comparison with commercial loans

na lly developed in the Congress govern-

ment under Rajiv Gandhis leadership in

the late 1980s. At a national conference

organised by the Confederation of Engi-

neering Industry (CEI) (predecessor of the

Confederation of Indian Industry (CII)),

Rajiv Gandhi (1988) pointed to the rela-

tive lack of FDI in the Indian economy

and the potential benets that can be

reaped by promoting such investment:

Our policy towards foreign investment is clear.

It is not an open door policy. We permit foreign

investment on our terms, in a wide range of

sectors within certain percentages of foreign

equity. These percentages can be relaxed in

areas of high technology, or where there is a

special contribution to exports. This basic

policy is sound and does not need any change.

Yet the actual inow of direct investment into

our economy is minuscule compared to inows

into other developing countries. Foreign

investment in the ASEAN countries is around

Rs 1,500 crore per year. Foreign investment

in socialist China is about Rs 2,000 crore per

year. Foreign investment in India is only

about Rs 100 crore. The external borrowing

has expanded over the past several years,

reecting our growing needs and absorptive

capability. But the ow of direct investment

has remained very small. Yet direct invest-

ment has some advantages over loans. Loans

have to be repaid whether investments are

productive or not. Investment leads to out-

ows only after there is production and

then too only when there is protWe can

absorb a larger ow of foreign investment, with

advantage to our economy, by speeding up

procedures and removing unnecessary irritants

(emphasis mine).

Two factors seem to have led Rajiv

Gandhi to support FDI inows. First, his

visit to Japan offered a chance to learn

from that countrys developmental expe-

rience.

5

Through this learning, he con-

rmed his belief in the signicance of

technology and a close tie between the

state and industry in the process of eco-

nomic development. He knew that for-

eign investment is the easiest way for

domestic industry to access advanced

technology. Second, his benign perspec-

tive on foreign capital was moreover

encouraged by the difculties of han-

dling external commercial borrowing.

NOTES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 69

The question was about devising indus-

trial strategies in India in a way to make

the relation between the state and

industry more cooperative. Nonetheless,

Rajiv Gandhi failed to open the Indian

market to foreign investors. This was

because domestic capital lobbied strongly

for protection from foreign capital.

Pro-FDI Inows, 1991 Onwards

The nancial difculties in the early

1990s brought new economic policies

on the agenda, especially in the area of

foreign investment. First, Montek Singh

Ahluwalia condentially submitted a new

policy paper titled Towards Restructur-

ing Industrial, Trade and Fiscal Policies to

the prime ministers ofce (PMO) in 1990.

6

The paper, in fact, became the original

design for the economic reforms that were

implemen ted in 1991. It suggested the

thorough deregulation of the industrial

sector, including foreign investment. For

example, it contained a scheme to incre ase

the equity of foreign investors from 40%

to 51% of the paid-up capital in domestic

companies in many sectors. Through this

scheme, foreign capital could actively

parti cipate in the process of industriali-

sation in India. Second, the Union Budget

1991-92 also showed the need of foreign

investment. In his budget speech, Man-

mohan Singh, who succeeded Yashwant

Sinha as the nance minister, strongly

supported FDI inows (GOI 1991a: 5). He

believed that FDI inows would provide

access to capital and technology that

could contribute to economic growth.

The imminent threat of a BOP crisis

and the consensus of key policymakers

for liberalisation led to the opening of

Indias economy to foreign capital. Since

the extensive economic reforms of 1991,

total FDI inows have steadily increased.

Interestingly, India has outpaced China

since 2006 in terms of FDI inows as a

proportion of gross xed capital formation

(Table 1). This means that FDI inows in

India have played a more important role

in capital formation compared to China

in recent years. Through the reforms of

1991, foreign capital could participate

in the process of Indias industrialisation

comparatively more easily than before

by enhancing its equity up to 51% in

domestic companies in many sectors.

When the plan for economic reforms

was unveiled in 1991, there were conict-

ing opinions. Many policymakers stro ngly

supported the so-called Montek paper

that outlined a comprehensive economic

vision for both Indian industry and

international relations.

7

However, some

key bureaucrats critically pointed to the

feeble position of the Indian state in

pursuing the reforms against the power

of vested interests such as rich farmers,

business groups, and trade uni ons. Dhar

(1990), a former principal secretary to

the prime minister when Indira Gandhi

was in ofce, and an assistant secretary

general of the United Nations, was one

of them. He was concerned about what

could happen to economic policies at a

time when there was pervasive political

fragmentation within a political party.

His comment on this is noteworthy: In

circumstances of poli tical fragmentation

economic policies are political weapons

in power struggles rather than solutions

to problems (p 26).

Political fragmentation and the power of

vested interests in fact strongly disturbed

the progress of the economic reforms of

1991. The rst response from Indian

society to the reform plan came from

domestic big business. Some dominant

business associations expressed diffe rent

opinions. The Associated Chambers of

Commerce & Industry (ASSOCHAM) argued

in favour of the need for free ow of

foreign investment while the Federation

of Indian Chambers of Commerce and

Industry (FICCI) opposed the liberalisation

of FDI policy. The FICCI, whose member-

ship is dominated by the indigenous busi-

ness groups, felt that the nal judgment

on whether or not such investment is

desirable should be left to the Indian

entrepreneurs.

8

A similar view in strongly

opposing foreign investment was again

observed after a few years when a BJP-led

government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee

attempted economic reforms in 1998,

although FICCI now laid emphasis on

sector-wise issues.

As another example of how the interest

of domestic big business inuenced the

reform process, the Bombay Clubs

swadeshi debates should not be missed.

The Bombay Club (this is more of a sym-

bolic term rather than a genuine one,

indicating a section of Indian big business

represented by the Bajaj, Birla, Thapar,

Modi, Godrej, Singhania and some others)

led by Rahul Bajaj, chairman and manag-

ing director of Bajaj Auto, was unhappy

with the deepened competition with for-

eign capital as the result of the reforms

(Chibber 2003). Centring on the CII and

the FICCI, it began to

demand a level playing eld

vis--vis foreign capital in

the Indian market. Its resist-

ance to economic reforms

was strengthened in late

1993 when the economic cri-

sis eased (Kochanek 1987).

While the Bombay Club

was opposing foreign invest-

ment by demanding contin-

ued tariff protection and

internal reforms prior to

opening the domestic market,

competition for lobbying to

pursue their interests among

business associations was

becoming more severe.

Lobbying by the domestic

big business to protect its

business interest against

foreign capital had been

considerable until the BJP-

led National Democratic

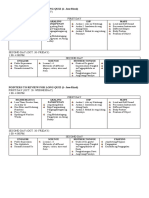

Table 1: FDI Inflows to India and China

Year FDI, Net Inflows FDI, Net Inflows As a % of Gross Fixed

(BoP, Current $) (% of GDP) Capital Formation

(Annual Average)

India China India China India China

1991 73,537,638 4,366,000,000 0.0 1.2

1992 276,512,439 11,156,000,000 0.1 2.6

1993 550,370,025 27,515,000,000 0.2 6.2

1994 973,271,469 33,787,000,000 0.3 6.0

1995 2,143,628,110 35,849,200,000 0.6 4.9

1996 2,426,057,022 40,180,000,000 0.6 4.7

1997 3,577,330,042 44,237,000,000 0.8 4.6

1998 2,634,651,658 43,751,000,000 0.6 4.3

1999 2,168,591,054 38,753,000,000 0.5 3.6

2000 3,584,217,307 38,399,300,000 0.8 3.2 1.9* 11.9*

2001 5,471,947,158 44,241,000,000 1.1 3.3 4.7 10.5

2002 5,626,039,508 49,307,976,629 1.1 3.4 4.6 10.4

2003 4,322,747,673 47,076,718,733 0.7 2.9 2.8 8.6

2004 5,771,297,153 54,936,483,255 0.8 2.8 2.7 8.2

2005 7,269,407,226 104,108,693,870 0.9 4.6 2.9 9.2

2006 20,029,119,267 124,082,035,620 2.1 4.6 6.6 6.4

2007 25,227,740,887 156,249,335,200 2.0 4.5 6.3 6.0

2008 43,406,277,076 171,534,650,310 3.5 3.8 9.9 5.8

2009 35,581,372,930 131,057,052,870 2.6 2.6 8.2 4.3

2010 26,502,000,000 243,703,434,560 1.6 4.1 4.4 4.4

2011 32,190,000,000 220,143,285,430 1.7 3.0 6.4 3.7

*Annual average from 1990-2000.

Source: World Development Indicators (various issues), World Investment Report

(various issues).

NOTES

january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 70

Alliance (NDA) government led by Vajpayee

took ofce. Vajpayees leader ship, espe-

cially in 1998 and 1999, witnessed a vigor-

ous debate on the Bombay Club and its

using the idea of swadeshi in opposing FDI

inows. As swadeshi was also the ideologi-

cal base of the BJP, the voice of domestic

big business in insisting on a level playing

eld was strong. P Chidambaram (2007)

who served as nance minister before the

NDA, for example, expressed his apprehen-

sion about the hostile attitude of Indian big

business towards foreign capital in his

autobiography. As he puts it: Rahul Bajaj

(and what survives of the Bombay Club)

maintains that money has colour. Accord-

ing to him, there is foreign money and

there is Indian money, and the latter has to

be preferred to the former (p 52).

Left- and Right-wing Opposition

The second response from Indian society

to the reforms came from social activists

who spoke for producers in the small

industries, farmers, artisans and con-

sumers. Social activists opposed dom estic

big business when the latter oppo sed the

reforms in the name of a level playing

eld. For them and the poor in society, big

business sought its own prot in the name

of swadeshi. Such a negative response

from society was not only towards

domestic big business but also towards

foreign capital. The response was often

expressed through agitations and attempts

to evict the MNCs. Because of these strong

agitations and political lobbies from

many interest groups in society, many for-

eign investors had to withdraw their

plans to embark on invest ment in India.

Interestingly, such agitations involved

either the left-wing political parties that

made alliances with the victims of the eco-

nomic reforms or extreme right-wing polit-

ical segments that aimed to protect the

interests of domestic companies or indige-

nous groups. Prasenjit Bose, who was the

convenor of the research unit in the CPI(M),

expressed his Partys position as follows:

9

There are two types of anti-FDI pictures from

our perspective. First is a grass-root level

resistance, which is protesting for people

who are displaced from their resources and

livelihood like land. Second is a sector-by-

sector approach at the macro-economic policy

level. We do not oppose the FDI inows of

every sector. We accept that we cannot avoid

globalisation. So we consider the sensitivity

of each sector (for opposing FDI inows).

Despite its nuanced understanding of

the inuence of globalisation in the Indian

market, the left-wing parties like CPI(M)

have had a central role in opposing FDI

inows by organising their trade unions

and opposing the managements of many

foreign companies in Indian industry.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

(RSS), has also opposed globalisation

and FDI inows. The Swadeshi Jagran

Manch (SJM) (self-reliance awa re ness

front) that was organised in 1994 by the

RSS has stronlgy resisted FDI inows

(Frankel 2005 (1978): 728-29). Its oppo-

sition activities were clearly obser ved

especially when Vajpayee was the prime

minister. The SJM often alleged that it

would conduct a social boycott of politi-

cal leaders and bureaucrats who negoti-

ated with the World Trade Organisation

and MNCs, by describing its opposition to

MNCs as the second war of Indias inde-

pendence with a slogan of MNCs quit

India; we wont accept globali sation.

10

Such struggles of foreign investors fac-

ing strong opposition from some sections

of society are still witnessed today in many

states in India, even though economic

institutions are obviously pro-FDI. The

anti-special economic zone movements in

many states, including Tamil Nadu and

Maharashtra, and the anti-Pohang Iron

and Steel Company (POSCO) movement in

Jagatsinghpur (Odisha) are well known.

One noteworthy thing in these agitations

against foreign capital and FDI projects is

that the issues raised and the strategies of

the opposition groups have become more

complicated. The issues have been arti-

culated in terms of livelihood, security and

environment besides the idea of swadeshi.

Another feature of this pro-FDI inows

period is the decreased role of the prime

minister in the process of FDI approval.

Instead, there is greater discretion exer-

cised by the chief ministers of the states

concerned. Compared to other economic

agendas, it is quite interesting to see the

overall reduction of prime ministers role

in the FDI approval process. V S Chauhan,

director of Foreign Investment Promo-

tion Board (FIPB), agreed with this per-

spective to some extent. In the course of

an interview, while stressing the two

different domains of the FDI process, deci-

sion and implementation, he said:

11

When there is no policy, then the decision is

taken at the highest level. When you clearly

demarcate a policy, then you do not need to

involve the PM. You take the PMs approval

only for the change of policy. ... It should be

seen as the steering role of PMO when there

was no clearly articulated policy. [When] the

policy has been articulated, its implementation

has to be left to the administrative ministries.

Why then has the signicance of the

states increased in the process of FDI

inows? The proportion of FDI proposals

that embark upon the automatic route

accounts for around 80% to 90% of all the

proposals.

12

The proposals then have to be

guided by each state where the FDI project

is planned. In cases of FDI proposals that

need to build plants for production (this

is called as the greeneld type of FDI),

each state consults the foreign investors

in order to provide them the necessities,

including land, electri city, water, and

some other infrastructural facilities, for

the establishment of the plants within

the provincial state (GOI 2002).

Interstate Competition

In order to demonstrate better perform-

ance than other states in approving more

FDI projects, competition among fal

states has intensied (FICCI 2012). We

have observed many chief ministers who

accelerate industrialisation in their states.

Chandrababu Naidu in Andhra Pradesh,

Narendra Modi in Gujarat, Jayalalithaa in

Tamil Nadu, and many others in Karnataka,

Odisha, Bihar, and recently in West Bengal

have attempted to promote FDI inows. As

a driving force of deepening competition

among states, not only liberalised ideas

from political leaders but also learning

from neighbouring states strongly works.

Regarding the positive effect of the

deepening of interstate competition in

attracting FDI inows and thereby

catc hing-up, Montek Singh Ahluwalia,

currently serving as the deputy chairman

of the Planning Commission, says:

13

The BIMAR[O]U states, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh,

Rajasthan, UP, and Odisha, if you spell the

bimaru, you should add o for Odisha. Now

look at these states. ...Quite a few of them are

catching up. ...Each state has investment con-

ferences, and images are created. The other

interesting thing is that states are actually

changing the images [as investment-friendly

ones]...maintenance [of good performance] is

NOTES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW january 18, 2014 vol xlix no 3 71

a very big problem... this maintenance should

be the job of all the state governments

charged. The central government helps them

to create capacities and the state governments

maintain their capacities.

Conclusions

This article has explored the dynamic

interaction between politics and institu-

tional changes in the area of FDI inows

in India. Drawing attention to three polit-

ical factors, the article has explained the

pattern of FDI inows in India that had

gradually evolved from the period of anti-

FDI inows (1969-75) to selective FDI

inows (1975-91), and nally to pro-FDI

inows (after the economic reforms of

1991). In the period of anti-FDI inows, the

article has shown that political struggles

between Indira Gandhi and her opponents

(called the Syndicate) within the Congress

Party had a signicant role in structuring

economic rules against foreign capital. In

the period of selective FDI inows, the

need for foreign investment began to be

discussed, especially in some selective

areas where foreign technology was nec-

essary in Indian industry. In this gradual

transformation of patterns, fresh ideas

from key policymakers who recognised

the advantages of FDI over commercial

borrowing played a signicant role. How-

ever, lobbying and interest group politics

involving domestic business groups against

FDI inows hindered the policymakers

from widely opening the domestic market

to foreign capital. But the momentous

transition from selective FDI inows to pro-

FDI inows was driven by the imminent

threat of nancial crisis and the consen-

sus of key policymakers for liberalisation.

Intensied competition between domestic

private capital and foreign capital in

Indian industry and between states has

led businesses to pay attention to social

concerns. The discussion particularly

draws attention to the fact that the states

and their politics have greatly inuenced

FDI inows at the state level. The political

economy of FDI inows across states is

dynamic as it is deeply related to the

complicated issues of coalition politics

between the centre and the states.

Notes

1 Foreign capital is both a political and economic

term in this research, while FDI is an economic

term. Foreign capital is a political class within the

boundary of domestic politics in a foreign

investment-hosting country as well as foreign

currency, especially equity shares, preference

shares, convertible preference shares, and convert-

ible debentures taken by any foreigner or foreign

company in the market of the host country.

2 For the political conicts between Indira

Gandhi and the Syndicate, see Kaviraj (1986);

Frankel (2005 (1978): chapters 7 and 10); Nayar

(2006: 107-34); Mukherji (2007: introduction);

Panagariya (2008: 50-51); Hewitt (2008: 81-82).

3 GoI (1969: Ch 14).

4 Ibid, same chapter.

5 Interestingly, some other political leaders both at

the centre and state levels also visited Japan for

learning the east Asian development strategies in

the 1980s. Their inspirations were in reality

embodied to devise industrial strategies in India

in a way to make the state and industry more

cooperative. For example, MGR (chief minister of

Tamil Nadu at that time) visited Japan with some

of his party members including C Ponnaiyan

(nance minister of Tamil Nadu at that time) in

order to learn about east Asian industrial devel-

opment. Interview with C Ponnaiyan in Chennai

on 31 January 2012. The strategies were outlined

in various government reports issued. See also

Abegglen and Etori (1981) and Sawhney (1985).

6 See Rohini Mohan, The Riddler on the Roof,

Tehelka, 19 May 2012. See also Acharya and

Mohan (2010), accessed on 17 May 2012.

7 See Institute of Economic Growth Delhi, Indus-

trial Policy: A Panel Discussion, New Delhi, 1990.

8 Political Bureau, Industrial Policy to Be

Approved Today, The Hindu, 21 July 1991,

accessed on 15 April 2012.

9 Interview at the head ofce of CPI(M) in Delhi

on 12 and 21 December 2011.

10 See Political Bureau, Swadeshi Manch Plans to

Probe Bureaucrats MNC Links, Business Stand-

ard, 28 February 1997; Rajesh Ramachandran,

Swadeshi Manch Puts Centre, MNCs on

Notice, The Times of India, 29 August 2000,

accessed on 6 June 2012.

11 Interview at MOF in North Block, Delhi on

21 March 2012.

12 Interview with Ashish Kumar (Director of FDI

Asia-Pacic Division) in the Department of

Industrial Policy & Promotion (DIPP) in Udyog

Bhawan, New Delhi on 15 March 2012.

13 Lecture in IIT Delhi on 3 March 2012. See also

Ahluwalia (2000).

References

Abegglen, James and Akio Etori (1981): The Secret

of Japans Economic Miracle, Bombay.

Acharya, Shankar and Rakesh Mohan, ed. (2010):

Indias Economy Performance and Challenges:

Essays in Honour of Montek Singh Ahluwalia

(New Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Ahluwalia, Montek S (1986): Balance-of-Payments

Adjustment in India, 1970-71 to 1983-84, World

Development, 14, No 8, pp 937-62.

(2000): Economic Performance of States in

Post-Reforms Period, Economic & Political

Weekly, Vol 35, No 19, pp 1637-48.

Bhandari, Bhupesh (2011): Once There Was the

Bombay Club... Business Standard, 8 July.

Chibber, Vivek (2003): Locked in Place: State-

Building and Late Industrialisation in India

(New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

Dhar, P N (1990): Constraints on Growth: Reections

on the Indian Experience (Delhi: Oxford Uni-

versity Press).

EPW (1976): Strength Has Nothing to Do with It,

Economic & Political Weekly, 11, No 47, pp 1809-10.

Encarnation, Dennis J (1989): Dislodging Multi-

nationals: Indias Strategy in Comparative

Perspective (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

FICCI (2012): Empowering India: Redesigning G2b

Relations (New Delhi: FICCI and Bain &

Company).

Frank, Andre Gunder (1977): Emergency of

Permanent Emergency in India, Economic &

Political Weekly, 12, No 11, pp 463-75.

Frank, Katherine (2001): Indira: The Life of Indira

Nehru Gandhi (London: Harper Collins

Publishers).

Frankel, Francine (2005): Indias Political Economy

1947-2004: The Gradual Revolution (New Delhi:

Oxford University Press) (original edition pub-

lished by Princeton University Press), [1978].

Gandhi, Rajiv (1988): Inaugural Address by the

Prime Minister of India, paper presented at

the National Conference Transformation of

Indian Engineering Industry, 19 April.

Ganguly, Sumit and Rahul Mukherji (2011): India

since 1980, The World since 1980 (New York:

Cambridge University Press).

GOI (1969): The Fourth Five-Year Plan (New Delhi:

The Planning Commission), Government of India.

(1980): Statement on Industrial Policy by

Dr Charanjit Chanana (Minister of State for

Industry), New Delhi.

(1991a): Budget 1991-92, edited by Government

of India, Ministry of Finance, New Delhi.

(1991b): Economic Survey 1990-91 (New Delhi:

Ministry of Finance), Government of India.

(1991c): Lok Sabha Debates 1991 (New Delhi:

Parliament).

(2002): Downstream Issues: Implementation

and Operation, New Delhi.

Gupta, Atul (1998): FDI and the Development

Process, The Economic Times, 24 October.

Hewitt, Vernon (2008): Political Mobilisation and

Democracy in India: States of Emergency (New

York: Routledge).

Joshi, Vijay and I M D Little (1991): India: Macro-

economics and Political Economy 1964-91 (New

Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Kaviraj, Sudipta (1986): Indira Gandhi and Indian

Politics, Economic & Political Weekly, 21,

No 38/39, pp 1697-708.

Kochanek, Stanley A (1987): Briefcase Politics in

India: The Congress Party and the Business

Elite, Asian Survey, 27, No 12, pp 1278-301.

(1995): The Transformation of Interest Politics

in India, Pacic Affairs, 68, No 4, pp 529-50.

Kohli, Atul (1989): Politics of Economic Liberalisa-

tion in India, World Development, 17, No 3,

pp 305-28.

Mooij, Jos (2005): The Politics of Economic Reforms

in India (New Delhi: Sage Publications).

Mukherji, Rahul (2007): Indias Economic Transition:

The Politics of Reforms, Critical Issues in Indian

Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

(2009): Interests, Wireless Technology, and

Institutional Change: From Government Mono-

poly to Regulated Competition in Indian Tele-

communications, The Journal of Asian Studies,

68, No 2, pp 491-517.

Nayar, Baldev Raj (2006): When Did the Hindu

Rate of Growth End? Economic & Political

Weekly, 41, No 19, pp 1885-90.

Nayar, Kuldip (2006): Scoop!: Inside Stories from

the Partition to the Present (New Delhi: Harper

Collins Publishers India).

Panagariya, Arvind (2008): India: The Emerging

Giant (New York: Oxford University Press).

Patel, I G (2002): Glimpses of Indian Economic Policy:

An Insiders View (New Delhi: Oxford Univer-

sity Press).

Prasenjit, Bose, ed. (2010): Maoism: A Critique from

the Left (New Delhi: LeftWord Books).

Sawhney, Dhruv (1985): Inaugural Address by

Shri Dhruv Sawhney (Chairman-Export of Aiei),

paper presented at the National Conference on

Engineering Exports, New Delhi, 22 March.

Sinha, Yashwant (2007): Yashwant Sinha: Confessions

of a Swadeshi Reformer (London: Penguin Books).

Tendulkar, Suresh D and T A Bhavani (2007):

Understanding Reforms: Post 1991 India (New

Delhi: Oxford University Press).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- WhittardsDocument7 pagesWhittardsAaron ShermanNo ratings yet

- Life of Pi Chapter QuestionsDocument25 pagesLife of Pi Chapter Questionskasha samaNo ratings yet

- Summons 20220511 0001Document52 pagesSummons 20220511 0001ElijahBactol100% (1)

- Indira Gandhi BiographyDocument4 pagesIndira Gandhi BiographySocial SinghNo ratings yet

- Digest-China Banking Corp. v. CIRDocument9 pagesDigest-China Banking Corp. v. CIRjackyNo ratings yet

- Chit ChatDocument5 pagesChit ChatErmin KicoNo ratings yet

- Natural Resources LawDocument6 pagesNatural Resources LawAubrey BalindanNo ratings yet

- Internal Assignment Applicable For June 2017 Examination: Course: Cost and Management AccountingDocument2 pagesInternal Assignment Applicable For June 2017 Examination: Course: Cost and Management Accountingnbala.iyerNo ratings yet

- Construction Safety ChetanDocument13 pagesConstruction Safety ChetantuNo ratings yet

- Toll BridgesDocument9 pagesToll Bridgesapi-255693024No ratings yet

- Land Use Management (LUMDocument25 pagesLand Use Management (LUMgopumgNo ratings yet

- Launch Your Organization With WebGISDocument17 pagesLaunch Your Organization With WebGISkelembagaan telitiNo ratings yet

- Pointers To Review For Long QuizDocument1 pagePointers To Review For Long QuizJoice Ann PolinarNo ratings yet

- Family Relations - San Luis v. San Luis (CJ CARABBACAN)Document2 pagesFamily Relations - San Luis v. San Luis (CJ CARABBACAN)juna luz latigayNo ratings yet

- Competition Law Final NotesDocument7 pagesCompetition Law Final NotesShubham PrakashNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions 2 Semester, S.Y. 2017-2018Document2 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions 2 Semester, S.Y. 2017-2018Jerlyn Mae Sales QuiliopeNo ratings yet

- 7759 Cad-1Document2 pages7759 Cad-1Samir JainNo ratings yet

- Read MeDocument21 pagesRead MeSyafaruddin BachrisyahNo ratings yet

- Acc Topic 8Document2 pagesAcc Topic 8BM10622P Nur Alyaa Nadhirah Bt Mohd RosliNo ratings yet

- BHMCT 5TH Semester Industrial TrainingDocument30 pagesBHMCT 5TH Semester Industrial Trainingmahesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Belly Dance Orientalism Transnationalism and Harem FantasyDocument4 pagesBelly Dance Orientalism Transnationalism and Harem FantasyCinaraNo ratings yet

- OPTEVA 522-562 - SETUP PC SIERRA REV Draft Version - STMIDocument3 pagesOPTEVA 522-562 - SETUP PC SIERRA REV Draft Version - STMIJone AndreNo ratings yet

- Rs-2n Midterm Exam 2nd Semester 2020-2021Document4 pagesRs-2n Midterm Exam 2nd Semester 2020-2021Norhaina AminNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton: by Kallika, Dipti, Anjali, Pranjal, Sachin, ShabnamDocument39 pagesLouis Vuitton: by Kallika, Dipti, Anjali, Pranjal, Sachin, ShabnamkallikaNo ratings yet

- TFL Fares StudyDocument33 pagesTFL Fares StudyJohn Siraut100% (1)

- Pyp As Model of TD LearningDocument30 pagesPyp As Model of TD Learningapi-234372890No ratings yet

- Response Key 24.5.23Document112 pagesResponse Key 24.5.23Ritu AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Charles Simics The World Doesnt End Prose PoemsDocument12 pagesCharles Simics The World Doesnt End Prose PoemsCarlos Cesar ValleNo ratings yet

- PAIN POINTS - Can Be Conscious (Actual Demand) or Unconscious (Latent Demand) That CanDocument8 pagesPAIN POINTS - Can Be Conscious (Actual Demand) or Unconscious (Latent Demand) That CanGeorge PaulNo ratings yet

- Yasser ArafatDocument4 pagesYasser ArafatTanveer AhmadNo ratings yet