Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poultry Genetics: History of Poultry: Chicken

Uploaded by

abidaiqbalansariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Poultry Genetics: History of Poultry: Chicken

Uploaded by

abidaiqbalansariCopyright:

Available Formats

Poultry Science Manual, 6

th

edition

1

POULTRY GENETICS

History of Poultry: Chicken

The ancestor of the domestic chicken, red jungle fowl

(Gallus gallus), can still be found today in regions of

South East Asia, including India, Burma, Malaysia,

Thailand, and Cambodia. The first of these birds is

believed to have been domesticated over 8000 years ago.

These jungle fowl are much smaller than most of todays

domestic varieties, and are a tropical species adapted to

live in much warmer conditions than most current

poultry. They are typically found in areas with thick

vegetation befitting of their name.

The jungle fowl were initially domesticated for either religious or entertainment purposes, and

are still used in sacrificial religious ceremonies or for cockfighting. The Romans were the first

society to develop and use the chicken as an agricultural animal. Romans even developed

specialized breeds including laying hens that could lay an egg a day; a rate similar to todays

commercial lines. The Romans expanded from just creating breeds of chicken to creating an

entire poultry industry which utilized concepts such as force feeding, hybrid vigor, and

caponizing. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire, the industry collapsed as well and

chickens became little more than farmyard scavengers. Those original breeds created by the

Romans were lost and the practice of keeping poultry for agricultural purposes fell out of favor

and did not resume until the 19

th

century.

In the 19

th

century poultry breeding came back into prominence in the

European region. As early as the year 1810, six breeds of poultry are

known to have existed in England (the Game, the White or English,

the Black or Poland, the Darkling, the Large or Strakeberg and the

Malay). Over a fifty-year period in England, formal poultry shows

were developed and many new breeds were created leading to the

formation of numerous Breed Societies. The modern breeds we have

today are mainly derived from two types of birds: the Asiatic and the

Mediterranean. Other breeds were developed by crossing breeds, and

the geographic origin of a breed is often indicated in their name (i.e.

Rhode Island Red).

During the last two centuries more than 300 breeds of chickens have been developed; however,

very few of these breeds have survived commercialization and many breeds have been lost

forever. The last 40 years have seen the rise of the commercial hybrid rather than new breeds of

chickens. These hybrids are of two main kinds; meat-type and egg-type. Both types of hybrids

have been selected to maximize the amount of production and minimize the amount of food

needed for that production. Today less than two dozen private companies worldwide create

hybrids based on specific production characteristics (body weight, growth rate, livability, pullet

Poultry Science Manual, 6

th

edition

2

quality, age at sexual maturity, egg weight, egg production,

eggshell quality, interior egg quality, and ability to convert

feed to eggs or meat).

Egg-laying types can be divided into light and medium

hybrids. The light hybrids are derived from the White

Leghorn. These birds lay white eggs and the mature female

weighs around 3.3 lbs. The medium hybrids are derived

from the Rhode Island Red and lay brown eggs with a

mature female weighing around 4.4 lbs. Both types of hybrids have been highly selected to

produce more and larger eggs while decreasing their body size and feed intake. These two types

of hybrids not only differ in their size, feather and egg color but also their temperament. White

hybrids are often better suited to be raised in cages, while brown hybrids do well in cage-free

systems.

The meat hybrids have been developed from breeds such as the Cornish and White Plymouth

Rock. These hybrids have been selected for growth rate, meat yield, and proportion of white

meat as well as high feed conversion. Today the majority of the meat lines are derived from the

Cornish on the male side. The Cornish gives the modern broiler chicken its broad breast, short

legs, and plump carcass. The majority of meat lines are also white feathered. White feathers are

preferable as they are easier to pick than dark feathers, and do not leave dark spots on the

carcass. To ensure that offspring are white feathered, male lines are bred to be dominant for

white plumage. Even when these males are crossed with a colored-feather female, the majority

of their offspring will have white, or nearly white, feathers. Another trait that has been selected

in the modern meat bird is yellow or white skin. This trait has been selected for solely because

of consumer preference.

History of Poultry: Turkey

The wild turkey originated in North America, as documented

by fossil records dating back over 10 million years. When

Europeans arrived in North America, two species of wild

turkeys were present. Turkeys have two misleading names.

First, their scientific name Meleagris gallapavo was

incorrectly given them by Linnaeus who thought that the

turkey was related to the guinea fowl. Secondly, the name

turkey itself is often misunderstood as well. The turkey was domesticated in Mexico over 2000

years ago by the Aztecs. When the Spanish explorers brought turkeys back to Europe, they were

called turkeys as most exotic birds entering Europe at that time (16

th

century) were entering

through the country of Turkey.

The domestic bird was then taken back into what is now Virginia by European colonists.

Interestingly turkeys were originally domesticated for their plumage not their meat. While the

Aztecs did use turkeys as a source of protein (meat and eggs), they were desired for their feathers

which were used for decoration. It was not until the 20

th

century that turkeys started to be

selected for meat production. By the late 1930s, mature males were weighing around 40 lbs.

Poultry Science Manual, 6

th

edition

3

with females weighing about half that. Commercial turkeys are bred specifically to have more

meat in the breast and thighs. White feathered turkeys are generally preferred, since they do not

have unsightly pigment spots on the skin when plucked.

As turkeys were selected for increased size, an undesirable side effect occurred. This un-

anticipated side effect was that the birds lost their ability to breed naturally. Artificial

insemination of breeder hens is now necessary; this is the only way commercial turkeys are able

to reproduce. Turkey semen can be chemically extended and used up to 24 hours after

collection.

Concepts and Methods of Poultry Genetic Selection:

Single Line: Breeder uses a closed flock, continuously selecting the better birds each

generation and breeding from them.

Hybrid Vigor: Outbreeding which results in increased quality of the hybrid offspring.

Male Line and Female Line: Crossing of a Male line only line with a Female online line. The

opposite sex of each line is destroyed at day 1 of age.

Strain Cross: Crossing of two or more different strains rather than selecting for traits within one

strain. Only a few desired traits are selected within each strain rather than all the desired traits in

one strain.

Two-line Cross: Allows for offspring to have positive traits from both lines, however, at a lower

rate than the original lines.

Three-line Cross: First a two-line cross is done then the offspring of that cross are crossed with a

third line to obtain more positive traits.

Four-line Cross: Two separate two line crosses are completed than the offspring of these two

crosses are bred to obtain offspring with traits from all four lines.

Strains used for crossing must nick: This means that the two lines that are being crossed must

complement each other.

Inbred Crosses: Crossing of related individuals to improve uniformity. This often reduces

performance. Performance can be restored by crossing lines.

Sex-linked Meat Lines: Certain feather colors and speed of feather growth can be linked to the

sex of the bird. The trait will only appear in one of the sexes, making separation of chicks at

hatch easier.

* Dr. Greg Archer, Assistant professor and extension specialist, Department of Poultry Science, Texas

A&M University, researched, developed, and prepared this topic. Kirk C. Edney, Ph.D., Instructional

Materials Service, Texas A&M University, edited and formatted this topic.

Poultry Science Manual, 6

th

edition

4

Structure and Flow of Genetics in the Poultry Industry:

Pedigree Farm

Great

Grandparent

Grandparent

Multiplier (parent)

Production Farms

Breeder

Farms

Primary

Breeder

Farms

You might also like

- Homestead ChickensDocument4 pagesHomestead ChickenslastoutriderNo ratings yet

- Poultry FarmingDocument4 pagesPoultry FarmingSubash_SaradhaNo ratings yet

- Breeds Varieties of Poultry - Chickens Turkeys Captive Game Birds - SliDocument130 pagesBreeds Varieties of Poultry - Chickens Turkeys Captive Game Birds - SliADNo ratings yet

- GRIT Perfect ChickensDocument7 pagesGRIT Perfect ChickensHan van Pelt100% (2)

- The Illustrated Guide to Chickens: How to Choose Them, How to Keep ThemFrom EverandThe Illustrated Guide to Chickens: How to Choose Them, How to Keep ThemRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Classification of Domestic BirdsDocument3 pagesClassification of Domestic BirdsJohn Remart EmpronNo ratings yet

- Online Research (Farm Animals)Document7 pagesOnline Research (Farm Animals)chynaNo ratings yet

- Pigs: Keeping a Small-Scale Herd for Pleasure and ProfitFrom EverandPigs: Keeping a Small-Scale Herd for Pleasure and ProfitRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- About Dairy Cows: Global Milk ProductionDocument8 pagesAbout Dairy Cows: Global Milk ProductionDewi argaNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Guide to Hobby Farm Animals: Raising Beef Cattle, Chickens, Ducks, Goats, Pigs, Rabbits, and SheepFrom EverandUltimate Guide to Hobby Farm Animals: Raising Beef Cattle, Chickens, Ducks, Goats, Pigs, Rabbits, and SheepMark McConnonNo ratings yet

- Artificial SelectionDocument13 pagesArtificial Selectionvindhya shankerNo ratings yet

- Thrifty Chicken Breeds: Efficient Producers of Eggs and Meat on the Homestead: Permaculture Chicken, #3From EverandThrifty Chicken Breeds: Efficient Producers of Eggs and Meat on the Homestead: Permaculture Chicken, #3No ratings yet

- Poultry lecNEWDocument31 pagesPoultry lecNEWJESPER BAYAUANo ratings yet

- Cattle - Types and Breeds - With Information on Shorthorns, the Hereford, the Galloway and Other BreedsFrom EverandCattle - Types and Breeds - With Information on Shorthorns, the Hereford, the Galloway and Other BreedsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Eggs and Raising Ready To Lay Pullets As A 4H or FFA ProjectDocument15 pagesEggs and Raising Ready To Lay Pullets As A 4H or FFA ProjectAthena KayeNo ratings yet

- On the Breeding, Rearing, and Fattening of Sheep - A Guide to the Methods and Equipment of Livestock FarmingFrom EverandOn the Breeding, Rearing, and Fattening of Sheep - A Guide to the Methods and Equipment of Livestock FarmingNo ratings yet

- Animals: Tecnico Profesional en Ingles Maria Fernanda Muñoz HernandezDocument16 pagesAnimals: Tecnico Profesional en Ingles Maria Fernanda Muñoz HernandezF E R N A N D A G U A P ANo ratings yet

- A Guide to Pig Breeding - A Collection of Articles on the Boar and Sow, Swine Selection, Farrowing and Other Aspects of Pig BreedingFrom EverandA Guide to Pig Breeding - A Collection of Articles on the Boar and Sow, Swine Selection, Farrowing and Other Aspects of Pig BreedingNo ratings yet

- Poultry Breeding and Selection: Muhammad Ashraf and Zaib Ur RehmanDocument14 pagesPoultry Breeding and Selection: Muhammad Ashraf and Zaib Ur RehmanZulfiqar Hussan KuthuNo ratings yet

- Chickens, 2nd Edition: Tending a Small-Scale FlockFrom EverandChickens, 2nd Edition: Tending a Small-Scale FlockRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Module 2 Poultry Species and NutritionDocument15 pagesModule 2 Poultry Species and NutritionIRENE SEBASTIANNo ratings yet

- ClassDocument14 pagesClassDan RicksNo ratings yet

- Raising Turkeys For FFA or 4HDocument16 pagesRaising Turkeys For FFA or 4HDragomir EduardNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Poultry IndustryDocument5 pagesExploring The Poultry IndustryFaizan MustafaNo ratings yet

- Class 4Document7 pagesClass 4Ajay kuhireNo ratings yet

- 12 - 42 - Ynthetic Cattle and Buffalo BreedsDocument15 pages12 - 42 - Ynthetic Cattle and Buffalo Breedsmuralidhar_mettaNo ratings yet

- History of The ChickenDocument1 pageHistory of The ChickenFachrezi Aldi Nur RohmanNo ratings yet

- ChickenDocument1 pageChickenJimmu CruzNo ratings yet

- Poly Mouth Rock Boiler Breed DetailsDocument5 pagesPoly Mouth Rock Boiler Breed DetailsGirish KumarNo ratings yet

- Sheep Facts PDFDocument8 pagesSheep Facts PDFAnnalie SalazarNo ratings yet

- This Article Was Originally Published Online in 1996. It Was Converted To A PDF File, 10/2001Document5 pagesThis Article Was Originally Published Online in 1996. It Was Converted To A PDF File, 10/2001Ahmed Moh'd El-KiniiNo ratings yet

- Ostrich Production 1Document5 pagesOstrich Production 1fembar100% (1)

- Ans 00 603MGDocument3 pagesAns 00 603MGghoshtapan4321No ratings yet

- Goat 234Document32 pagesGoat 234owen manasahNo ratings yet

- PoultryDocument15 pagesPoultryMekbib MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Breeds and Types of PoultryDocument22 pagesBreeds and Types of PoultryTenika RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Pig BreedsDocument8 pagesPig BreedsDelicious DelightNo ratings yet

- Uniersity of Hargeisa: College of Agriculture, Veterinary and Animal SceinceDocument64 pagesUniersity of Hargeisa: College of Agriculture, Veterinary and Animal SceinceZulfiqar Hussan KuthuNo ratings yet

- BaDocument4 pagesBalaw crazeNo ratings yet

- La151 Beef BreedsDocument5 pagesLa151 Beef Breedsapi-3030435880% (1)

- 05 Turkey-Production-2022Document70 pages05 Turkey-Production-2022Alfred James SorianoNo ratings yet

- Swine ProductionDocument56 pagesSwine ProductionGerly NacionalesNo ratings yet

- Everything Chickens: Coops & CareDocument45 pagesEverything Chickens: Coops & CareChicken coop100% (1)

- Breeds of Beef Cattle Ritchie Jan2009 PDFDocument95 pagesBreeds of Beef Cattle Ritchie Jan2009 PDFPurcar Cosmin100% (1)

- Rase GovedaDocument5 pagesRase GovedaИлијаБаковићNo ratings yet

- Local Media7929427703500344030Document21 pagesLocal Media7929427703500344030Sheena Marie B. AnclaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Dairy Cattle ProductionDocument19 pagesChapter 2 Dairy Cattle ProductionseidNo ratings yet

- Duck Rearing MethodsDocument10 pagesDuck Rearing MethodspunyasNo ratings yet

- Poultry CHICKENDocument57 pagesPoultry CHICKENAnnalie SalazarNo ratings yet

- Livestock and Farms Animals: Pigs & SheepDocument8 pagesLivestock and Farms Animals: Pigs & SheepVICTOR ALFONSO LEON SABOGALNo ratings yet

- Pig BreedsDocument8 pagesPig BreedsChong BianzNo ratings yet

- Goose Production Systems: Roger BucklandDocument10 pagesGoose Production Systems: Roger Bucklanddiagnoz7auto7carsvanNo ratings yet

- Poultry Production - IntroductionDocument24 pagesPoultry Production - IntroductionMarson Andrei DapanasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 PoultryDocument12 pagesChapter 5 PoultryseidNo ratings yet

- 1c. History of Animal BreedingDocument6 pages1c. History of Animal BreedingNishant ShahNo ratings yet

- GlossaryDocument4 pagesGlossaryabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Oven Et Al-2009-Human MutationDocument9 pagesOven Et Al-2009-Human MutationabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- 4HB0 01 Que 20160113Document32 pages4HB0 01 Que 20160113abidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Darbar e DilDocument156 pagesDarbar e Dilapi-370666150% (2)

- 4BI0 2B Que 20160114 PDFDocument16 pages4BI0 2B Que 20160114 PDFabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- 4CH0 1C Que 20160118 PDFDocument32 pages4CH0 1C Que 20160118 PDFabidaiqbalansari100% (1)

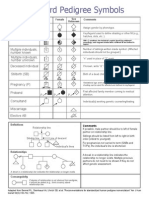

- Standard Pedigree SymbolsDocument1 pageStandard Pedigree SymbolsabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Chicken Anatomy and PhysiologyDocument16 pagesChicken Anatomy and Physiologyabidaiqbalansari100% (1)

- 4BI0 1B Que 20160112Document32 pages4BI0 1B Que 20160112Rokunuz Jahan RudroNo ratings yet

- Blotting TechniquesDocument3 pagesBlotting TechniquesabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Model 422 Electro-Eluter Instruction Manual: Catalog Numbers 165-2976 and 165-2977Document16 pagesModel 422 Electro-Eluter Instruction Manual: Catalog Numbers 165-2976 and 165-2977abidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Koreans Revealed by MtdnaDocument10 pagesKoreans Revealed by Mtdnaabidaiqbalansari0% (1)

- Methods of Mating and Artificial Insemination in PoultryDocument7 pagesMethods of Mating and Artificial Insemination in PoultryabidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Reanalysis and Revision of The Cambridge Reference Sequence For Human Mitochondrial DNA.Document1 pageReanalysis and Revision of The Cambridge Reference Sequence For Human Mitochondrial DNA.abidaiqbalansariNo ratings yet

- Miller Salting Out 1988Document1 pageMiller Salting Out 1988Rafael AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Stud Dog ContractDocument4 pagesStud Dog Contract4geniecivilNo ratings yet

- Bombay CatDocument2 pagesBombay CatprosvetiteljNo ratings yet

- Breeds Dogs Cats 1Document31 pagesBreeds Dogs Cats 1Chai YawatNo ratings yet

- Perth Sunday Times - Week 10 - 20/6/2010Document1 pagePerth Sunday Times - Week 10 - 20/6/2010John_Bishop_3317No ratings yet

- Horses Ranking Jumping March 2012Document115 pagesHorses Ranking Jumping March 2012drwizNo ratings yet

- Hong Kong and Macao Cat Club-2014 - 5 Tasik Jalan Ampang Jalan Hulu KELANG, Malaysia Show Date:9/21/2014Document1 pageHong Kong and Macao Cat Club-2014 - 5 Tasik Jalan Ampang Jalan Hulu KELANG, Malaysia Show Date:9/21/2014api-204404759No ratings yet

- Berks County 4-h Horse Council Model Horse Show Packet 2016Document8 pagesBerks County 4-h Horse Council Model Horse Show Packet 2016api-306705817No ratings yet

- Radio Ranch RottweilersDocument11 pagesRadio Ranch RottweilersPam Crump BrownNo ratings yet

- Raising Turkeys For FFA or 4HDocument16 pagesRaising Turkeys For FFA or 4HDragomir EduardNo ratings yet

- Major Swine BreedsDocument1 pageMajor Swine BreedsDana Dunn100% (1)

- Heterosis Studies For Yield and Yield Attributing Characters in Brinjal (Solanum Melongena L.)Document5 pagesHeterosis Studies For Yield and Yield Attributing Characters in Brinjal (Solanum Melongena L.)Ade MulyanaNo ratings yet

- My Shetland Sheepdog PuppyDocument4 pagesMy Shetland Sheepdog Puppyapi-213368444No ratings yet

- Breed Classification PDFDocument3 pagesBreed Classification PDFahoNo ratings yet

- Diallel Seleective MatingDocument13 pagesDiallel Seleective MatingVinaykumar s nNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Bos Taurus Bos Indicus Breed Crosses With Straigttbred Bos Indicus Breeds of Cattle For Maternal and Individual TraitsDocument7 pagesComparison of Bos Taurus Bos Indicus Breed Crosses With Straigttbred Bos Indicus Breeds of Cattle For Maternal and Individual TraitsManuel Vegas0% (1)

- Beef Cattle Breeds, Breeding and ReproductionDocument15 pagesBeef Cattle Breeds, Breeding and ReproductionJohnmark GullesNo ratings yet

- Editorial Three Bars PDFDocument1 pageEditorial Three Bars PDFJan HorsemanNo ratings yet

- Hybrid Rice Breeding Seed ProductionDocument41 pagesHybrid Rice Breeding Seed ProductionGENIUS1507No ratings yet

- Breeds of Livestock - Hereford Cattle Hereford: EnglandDocument5 pagesBreeds of Livestock - Hereford Cattle Hereford: EnglandTamrinSimbolonNo ratings yet

- Norwegian Forest CatDocument5 pagesNorwegian Forest CatNenad YOvanovskyNo ratings yet

- The ShorthornsDocument9 pagesThe Shorthornsbima ramadhanNo ratings yet

- Poodle Papers Winter 2006Document40 pagesPoodle Papers Winter 2006PCA_website100% (8)

- Rabbits BreedingDocument6 pagesRabbits BreedingMatthew BerryNo ratings yet

- Kelso - The Smartest Fighting Rooster and The Magic of Crossbreeding Reach UnlimitedDocument7 pagesKelso - The Smartest Fighting Rooster and The Magic of Crossbreeding Reach UnlimitedJustine Bryan Delfino GavarraNo ratings yet

- Sop Klinik Hewan 3Document1 pageSop Klinik Hewan 3alfeni resti andariNo ratings yet

- Breeds of LivestockDocument24 pagesBreeds of LivestockAdiol Bangit AowingNo ratings yet

- Studi Perbandingan Kualitas Fisik Daging Babi BaliDocument4 pagesStudi Perbandingan Kualitas Fisik Daging Babi BalidewiardianiNo ratings yet

- G-10 Biology, 2.3 Heredity and BreedingDocument2 pagesG-10 Biology, 2.3 Heredity and BreedingYohannes NigussieNo ratings yet

- Breeding Field Crops and Vegetables in Croatia: ReviewDocument13 pagesBreeding Field Crops and Vegetables in Croatia: ReviewDora ZidarNo ratings yet

- 1013 Adba - IngDocument6 pages1013 Adba - IngKatbull100% (1)

- Pocket Guide to Flanges, Fittings, and Piping DataFrom EverandPocket Guide to Flanges, Fittings, and Piping DataRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (22)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessFrom EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessNo ratings yet

- To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignFrom EverandTo Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (137)

- Marine Structural Design CalculationsFrom EverandMarine Structural Design CalculationsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- An Eagle Named Freedom: My True Story of a Remarkable FriendshipFrom EverandAn Eagle Named Freedom: My True Story of a Remarkable FriendshipNo ratings yet

- The Illustrated Guide to Chickens: How to Choose Them, How to Keep ThemFrom EverandThe Illustrated Guide to Chickens: How to Choose Them, How to Keep ThemRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Carpentry Made Easy - The Science and Art of Framing - With Specific Instructions for Building Balloon Frames, Barn Frames, Mill Frames, Warehouses, Church SpiresFrom EverandCarpentry Made Easy - The Science and Art of Framing - With Specific Instructions for Building Balloon Frames, Barn Frames, Mill Frames, Warehouses, Church SpiresRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Advanced Modelling Techniques in Structural DesignFrom EverandAdvanced Modelling Techniques in Structural DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Bird Life: A Guide to the Study of Our Common BirdsFrom EverandBird Life: A Guide to the Study of Our Common BirdsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- My Parrot, My Friend: An Owner's Guide to Parrot BehaviorFrom EverandMy Parrot, My Friend: An Owner's Guide to Parrot BehaviorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- CONVERSATIONS WITH COSMO: AT HOME WITH AN AFRICAN GREY PARROTFrom EverandCONVERSATIONS WITH COSMO: AT HOME WITH AN AFRICAN GREY PARROTRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Green Roofs, Facades, and Vegetative Systems: Safety Aspects in the StandardsFrom EverandGreen Roofs, Facades, and Vegetative Systems: Safety Aspects in the StandardsNo ratings yet

- Birds Off the Perch: Therapy and Training for Your Pet BirdFrom EverandBirds Off the Perch: Therapy and Training for Your Pet BirdRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Pile Design and Construction Rules of ThumbFrom EverandPile Design and Construction Rules of ThumbRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Structural Steel Design to Eurocode 3 and AISC SpecificationsFrom EverandStructural Steel Design to Eurocode 3 and AISC SpecificationsNo ratings yet

- Flow-Induced Vibrations: Classifications and Lessons from Practical ExperiencesFrom EverandFlow-Induced Vibrations: Classifications and Lessons from Practical ExperiencesTomomichi NakamuraRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- A Sailor, A Chicken, An Incredible Voyage: The Seafaring Adventures of Guirec and MoniqueFrom EverandA Sailor, A Chicken, An Incredible Voyage: The Seafaring Adventures of Guirec and MoniqueNo ratings yet

- Structural Cross Sections: Analysis and DesignFrom EverandStructural Cross Sections: Analysis and DesignRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)