Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Waley Belgrade

Uploaded by

BabiEspíritoSantoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Waley Belgrade

Uploaded by

BabiEspíritoSantoCopyright:

Available Formats

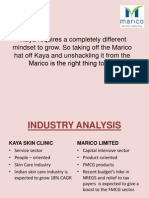

Planning Perspectives

Vol. 26, No. 2, April 2011, 209235

ISSN 0266-5433 print/ISSN 1466-4518 online

2011 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/02665433.2011.550444

http://www.informaworld.com

From modernist to market urbanism: the transformation of New Belgrade

Paul Waley*

School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK

Taylor and Francis RPPE_A_550444.sgm 10.1080/02665433.2011.550444 Planning Perspectives 0266-5433 (print)/1466-4518 (online) Original Article 2011 Taylor & Francis 26 20000002011 PaulWaley P.T.Waley@leeds.ac.uk

This paper introduces two starkly contrasting faces of recent European urbanism, and shows

how they have shaped the same urban territory, New Belgrade. In the first place, it outlines

the central dilemmas and difficulties around the construction of a large modernist city in

Europe, and secondly, it explores the modifications undertaken in order to accommodate a

radically different, consumption-oriented society. The location for this enquiry is the largest

municipal district within Belgrade. New Belgrade, with its immense size and expanse (over

40 sq km and a population of about 250,000), grand boulevards and massive apartment

buildings lined up in numbered blocks, is a mixture of modernist vision and socialist

planning, far larger than any comparable urban district in Central and Eastern European

cities. Designed as a federal capital for Titos Yugoslavia, it rapidly became a

predominantly residential suburb. New Belgrade is now being re-positioned and partly re-

built as a business centre in a process of change driven largely by international capital, with

international companies investing in the construction of large retail, leisure and business

facilities. At the same time, open spaces are being filled in, often with up-market housing.

The paper provides an overview of some of the plans and controversies that surrounded the

citys construction and an outline of the modifications that have transformed New Belgrade

since.

Keywords:

New Belgrade; modernism; socialist urbanism; urban change; market urbanism

Paradigmatic modernist urbanism

New Belgrade is one of the biggest if not, the biggest of the new cities that sprang up on

the outskirts of the major urban settlements of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) during the

Communist period. It is however different in a number of important respects from places such

as Nowa Huta, the steel city that stands next door to Krakow, or Petr

[ zcar on]

alka, the Bratislava

district on the south side of the Danube. It was designed with a strategic political intent: to

serve as the capital of the Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. Never completed, it has become a

fascinating landscape testimony to changing concepts and practices in urban design and urban

policy over the last 60 years. Today, with its 4100 hectares it is easily the largest of Belgrades

16 districts. A city within the city, its population of about a quarter million would today make

it Serbias third largest urban settlement.

New Belgrade is, in the first place, a paradigm for the intermingling of modernism and

socialism in urban form and space. It is, secondly and more recently, paradigmatic of post-

modern and post-socialist urbanism and of the attendant insinuations of the neo-liberal market

into modernist urban form and space. It is a textbook case, and is therefore an excellent territory

for telling wider stories both about modernist and socialist urban space and about its post-

modernist and post-socialist sequel. It is also, as Hirt argues, a near-anomaly in post-communist

*Email: p.t.waley@leeds.ac.uk

z

210

P. Waley

urban change, showing that prime location and quality of development may beat the grim

predictions of some scholars issued during the 1990s that the communist districts would

inevitably become ghettoes of decay.

1

Paradigmatic it may be, but it bears notable differences both from Western modernism and

Soviet socialist realism.

2

While New Belgrade illustrates patterns of change in CEE, it does so

in extreme ways. And yet, strangely, it has seldom been inserted into histories of modernist

and socialist urbanism. Why should this be so? Part of the answer probably lies in the distinc-

tive nature of its genesis, and part in the destructive nature of Yugoslavias disintegration.

Unlike Petr

[ zcar on]

alka, New Belgrade was not intended to be a residential district. Unlike Nowa

Huta, industry was not its raison-dtre. That it became (largely if not totally) a giant residen-

tial suburb is a commentary on the projects lack of economic sustainability Yugoslavia

simply could not afford to realize such an ambitious project. But it was far from ever becoming

just another monotonous series of high-rise apartment blocks. The lively architectural

ambience that existed in Socialist Belgrade, in frequent contact with developments in Western

Europe and elsewhere, ensured that the new city within a city was changing form and

appearance in response to stimuli from elsewhere.

3

Recent years have seen a notable (if still relatively specialized) recrudescence of interest in

New Belgrade, mainly but not exclusively among architects, sociologists and others with a

professional interest in the city. This follows on from and refers back to an earlier round of

comment and critique in which the thoughts of Henri Lefebvre and the work of Milo

[ s car on]

Perovi

[ cacut e]

figure prominently.

4

The tendency in this contemporary writing is to register horror at the

despoliation of a rare example of modernist planning even as it expresses sympathy for

Lefebvres call for recognition that the city is complex. As Dimitrijevi

[ cacut e]

points out, there is

an underlying and devastating irony in New Belgrade that a city conceived to stand for

socialist values is now a repository for the logic of untrammelled capital accumulation.

5

At the

same time, it would be a mistake to exaggerate a crude binary distinction between a socialist/

modernist period in New Belgrades development and a much more recent market-led trans-

formation. While a number of different chronologies have been advanced, it probably makes

most sense to see a more or less continual process of change in New Belgrade, punctuated by

a number of significant developments. There is, however, a final irony in the story of New

Belgrade, as Mari

[ cacut e]

et al. argue, that there exists an appreciation of New Belgrade among its

inhabitants present not only in everyday life, but also in literature, movies, and music indicat-

ing coexistence of New Belgrades inhabitants with their environment.

6

This paper represents an attempt to address some of these ironies and apparent contradic-

tions while telling the story of New Belgrades growth and mutations. The paper starts with a

discussion of some salient characteristics of socialist cities within which New Belgrade can be

set. The main sections of the paper present an account of the development of New Belgrade

that juxtaposes transformations in the built environment with a sense of daily lived experi-

ences, setting this within the context of the momentous changes that have affected Yugoslavia

and Serbia during this period. In doing so, I will argue for a reading of New Belgrade that

emphasizes the nature of the urban landscape as mirror of social change. The very nature of

the never-complete New Belgrade, with its large open spaces and broad avenues, has, I will

argue, made it particularly prone to the construction of the built landscape of neo-liberal

capital. These accretions have multiplied to the point where they now populate nearly all the

remaining empty plots, creating thus a patchwork of different styles of urbanism and a highly

z

s c

c

c

Planning Perspectives

211

distinctive record of changing approaches to urban development and urban life. They provide

an unusually complete setting from which to explore the broader issues surrounding the nature

of modernist and socialist and post-modernist and post-socialist urbanism. It is in this sense

that New Belgrade manages to be both paradigmatic and exceptional.

Modernist urbanism, socialist urbanism

The first stone for New Belgrade was laid in 1948, the year of the break with the Soviet Union.

This is an important pointer to the way the new district developed. Unusually, New Belgrade

was both a modernist city and a socialist city. It was both modernist and socialist in its adher-

ence to a geometric street plan and in its combination of a separation of functions and provision

of services within the housing blocks. Under socialism, urban form and space were seen as

ways of shaping and improving society in a direction congenial to socialist ideals, but socialist

cities in practice varied enormously.

7

Modernist urbanism was of course predicated on the

belief that urban form could be used as a conditioning tool for society.

Discussion of socialist urbanism cannot be conducted in isolation from consideration of the

modernist movement. But while the influence of the Congrs Internationaux dArchitecture

Moderne (CIAM), the Athens charter and Le Corbusier should not be underestimated, socialist

urbanism cannot simply be equated with modernist urbanism. After all, the victory of the

Urbanists in the USSR in their debates with contemporaries who favoured a dismantling of the

urban legacy was followed not long afterwards by the triumph of socialist neo-classicism,

which had little in common with modernist ideals.

8

Modernist urbanism has much more

readily identifiable and consistent features than does socialist urbanism while of course lacking

socialisms ideological foundations. However, they share a backbone of central characteristics,

from which each diverges at various times in different places. These include:

(1) A fundamental faith in the centrality of the plan. The plan was the charter for a more

ordered future.

(2) Functional zoning, a key tenet of modernist urbanism.

(3) A generous use of space. This was made possible in socialist cities as a result of state

ownership of land, a feature of the under-urbanization characteristic of socialist

urbanism.

9

Open spaces formed an important part of modernist plans.

(4) Green space. There was a specific emphasis on the importance of green space.

(5) An emphasis on the city as locus for production and widespread provision of land for

industry.

10

(6) The use of industrialized and therefore standardized building techniques.

11

(7) A parallel sense of standardized, uniform human life.

(8) Large housing estates, characteristic of all CEE cities. In Soviet cities, the neighbourhood

units,

mikro rayoni

, showed the influence of various modernist currents of thought.

12

(9) Building

ex novo

. New cities sprang up from Siberia to Brazil.

New Belgrade incorporates or reflects many of these common features. And it encapsulates a

further one: Projects in socialist new towns were hardly ever completed.

13

In a similar vein, New Belgrade reflects many of the changes that have overtaken CEE

cities in the last 20 years including the introduction of a planning regime that is subservient to

212

P. Waley

the dictates of the market and the requirements of international capital and a restructuring of

urban areas leading to the development of a central business district and the growth of suburbs

and beyond them an urban sprawl.

Market-oriented planning has clearly become the central tenet in Serbia, as it has in the rest

of CEE. Ta

[ scedi l ]

an-Kok refers to opportunity-led planning with its role call of consultants, archi-

tects and property developers and to corrective planning, a regime in which public authorities

are forced to be flexible to attract inward investment.

14

There is a clear link between this looser

control exercised by authorities operating within a neo-liberal regulatory environment and the

incidence of black market activity. Petrovi , for example, argues that Urban governance in

post-socialist cities is more tolerant of illegal practices.

15

Ironically, the discourse and

practice of participation appears to be missing from the current style of entrepreneurial

governance. In the context of Sofia, Hirt notes the technocratic top-down nature of planning.

The same view on the training and professional outlook of planners is expressed by Vujo

[ s car on]

evi

[ cacut e]

and Nedovi

[ cacut e]

-Budi

[ cacut e]

.

16

They see planning legislation and its instrumentalization in the 2001

Regional Spatial Plan of the Belgrade Administrative Area and the 2003 Master Plan of

Belgrade as taking a narrow technocratic view of the role of planning.

Entrepreneurial urban governance has suffused the whole of CEE, including the Yugoslav

successor states. Within this model, FDI plays a transformative role.

17

The influx of capital invest-

ment from Western Europe and North America, as well as Japan and Korea, has created a new

hierarchy of cities, with a rapid development of central cities and under urbanization in smaller

cities of a newly cast periphery. According to this extension of world city thinking, this new

hierarchy is fashioned by the differing nature of FDI. Corporate regional headquarters, supported

by an array of advanced producer services, have already transformed the three largest cities of

the CEE countries, Budapest, Prague and Warsaw, and are having similar effects on Moscow.

On the ground, a process of spatial restructuring has occurred as a result of which the cities

of CEE have developed features previously more familiar in the urban areas of Western

Europe. Alongside the creation of CBDs and the process of suburbanization have come other

phenomena such as the commercialization and privatization of sites vacated by industry and a

growing number of hypermarkets and shopping malls in peripheral areas of large cities. At the

same time, the commodification of urban space and the diffusion of extra-legal construction

have led to a growing impromptu infill urbanization, often through the construction of

commercial buildings.

18

Privatization has triggered socio-spatial segregation, or, what

Stanilov refers to as Balkanisation of the urban fabric.

19

Yugoslav cities have not been immune to these changes. But many of them have occurred

somewhat later or in intensified form as a result of the far more disruptive and retarded nature

of transition in the former Yugoslav countries.

20

And, as we shall see, many of these develop-

ments are visible in contemporary New Belgrade. However, perhaps because of what is

perceived as the exceptional nature of the post-Yugoslav tradition, and with a few exceptions

many of which are listed above, consideration of the ex-Yugoslav case has been largely absent

from wider discussion.

The planning and early construction of New Belgrade

New Belgrade occupies what was once a highly strategic site between two rivers, the Danube

and the Sava, and between two empires, the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian. Plans for

s

c

s c

c c

Planning Perspectives

213

construction of a new settlement on the marshes between the existing settlements of Belgrade

and Zemun had existed during the first incarnation of the Yugoslav state, in the 1920s and

1930s. The 1923 Master Plan for Belgrade envisaged the construction of luscious neo-

baroque avenues and boulevards, but all that materialized of this plan on the far bank of the

Sava was Belgrade Fair, which contained an eclectic mix of modernist and more traditional

pavilions and which was later transformed by the occupying Nazis into an extermination

camp.

21

The destruction of about one-third of Belgrade during both German and allied air raids in

the Second World War and the establishment of a socialist republic with its capital in

Belgrade gave a new impetus and significance to the idea of constructing a federal capital

outside the existing urban settlement. The first post-war plan was drawn up by Nikola

Dobrovi

[ cacut e]

, who had already established himself as the countrys pre-eminent architect. His

plan for New Belgrade had streets radiating out from a central station and terraces cascading

down to the river in an urban rendering of some formal French garden and opening up a

vista to the old town. This plan formed the basis for the drafting of ground rules for a series

of ensuing competitions for the design of New Belgrade. The fan shape was, however,

dropped in favour of orthogonal blocks, mainly square, and a central axis linking two focal

points, the new federal executive building (SIV Savezno Izvrsno Vece) and the railway

station.

22

A whole series of plans were announced for New Belgrade in the 1950s, after a hiatus

caused by the break with Moscow and the many associated disruptions.

23

Most of these have

been criticized for adhering too rigidly to Corbusian prescriptions or for blindly transferring

Lucio Costas plans for Brasilia, and it is worth bearing in mind in this context the links

between Yugoslav architects and the CIAM.

24

Milo

[ s car on]

Perovi

[ cacut e]

, who staged an influential

intervention in later debates about the future of the central axis and was himself an influential

architect at the University of Belgrade, accused his fellow architects of adhering to an out-

dated over-functional approach that failed to take on board revised thinking aired at the

CIAMs Aix-en-Provence congress held in 1953. Perovi saw two phases in work on New

Belgrade, an early one in which Dobrovi and other great architects participated, and a later

one without them.

The plan that was finally adopted was a conflation of the two winning entries to a national

competition organized and carried out in 1958 and 1959. It was designed around a central

axis, running from the federal executive building to the station, which consisted of buildings

with commercial, cultural and recreational functions, built around a central open space. Plans

to include federal government ministries along this central axis were dropped during the

1950s (Figure 1).

25

The central axis as envisaged in this plan was the subject of warm appre-

ciation from Aleksandar Djordjevi

[ cacut e]

, who was the head of the citys Town Planning Institute:

The monumental axis from the Federal Executive Council building to the new railway

station is no longer only the main street of New Belgrade, but a point to which all the

inhabitants of Belgrade and guests and visitors to the Yugoslav capital will be capital will be

attracted.

26

Figure 1. Branko Petri i s 1957 plan for New Belgrade. According to this plan, influential but unrealised in its detail, the central axis was to be flanked by commercial buildings, while government buildings were to border on the lake. Photograph reproduced from

Novi Beograd, 1961

by courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of Belgrade (Urbanisti ki zavod Beograda).

While this plan was never realized, three landmark buildings were completed in New

Belgrade, mitigating what was otherwise to become an exclusively residential landscape, and

for these, three separate architectural competitions were held. The most significant of the

three buildings was the palace for the Federal Executive Council (SIV; Figure 2). The

c

s c

c

c

c

214

P. Waley

winning entry was subsequently modified in the second half of the 1950s by Mihailo

Jankovi , who went on to become, in Kuli s words, the unofficial court architect to Titos

regime.

27

The resultant building presents itself as an unusual compromise between two prev-

alent contemporary tendencies, the one modernist, light and clean, suggesting the lines and

forms emanating from Brasilia, the other, perhaps less visible on the exterior, the vernacular

c c

Figure 1. Branko Petri[ ccar on] i[ cacut e] s 1957 plan for New Belgrade. According to this plan, influential but

unrealized in its detail, the central axis was to be flanked by commercial buildings, while government

buildings were to border on the lake.

Source: Photograph reproduced from Novi Beograd, 1961 courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of

Belgrade (Urbanisti[ ccar on] ki zavod Beograda).

c c

c

Planning Perspectives

215

references of a classicized modernism. While this building is very much one of a kind, the

second of the three landmark buildings, the CK building, housing the Central Committee

(Central Komitet) of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia eventually materialized in the

guise of a fairly standard internationalist modernist office block, showing the clear influence

of Mies van der Rohe. It dominated its environs, allowing for all-round observation, fittingly,

one might argue, for the headquarters of the Central Committee of the League of

Communists.

Figure 2. The former Federal Executive Council building, one of the great showpieces of New Belgrade, now rather under-used (this and other photographs of contemporary New Belgrade by the author).

While the CK building was placed in a prominent position at the entry point to New

Belgrade for those crossing the river from the old city, the third of the landmark buildings was

located more discretely on the banks of the Danube on the far side of the Federal Executive

building (Figure 3). This was the Yugoslavia Hotel (Hotel Jugoslavija), built over a number of

years between 1947 and 1961, as a prestigious riverside lodging for visiting foreign guests.

28

These three buildings were the only completed expressions of New Belgrades assumed role

as federal capital, and although the plans to build government offices along the central axis were

soon aborted, they were to have been joined by other state and diplomatic buildings. Foreign

embassies were to be encouraged to move to New Belgrade, and, while several were reported

to be considering a move, only the Chinese government memorably, as we shall see later

moved its embassy to this bank of the Sava. In addition, there were plans to locate a number

of museums and other cultural buildings in New Belgrade, on land near the confluence of the

Sava and the Danube next to the CK building.

29

Of these, only one was completed, the Museum

of Contemporary Art (Muzej Savremene Umetnosti), the work of Ivan Anti

[ cacut e]

and Ivanka c

Figure 2. The former Federal Executive Council building, one of the great showpieces of New

Belgrade, now rather under-used.

Source: This and other photographs of contemporary New Belgrade by the author.

216

P. Waley

Figure 3. New Belgrade, showing the Sava and Danube rivers, and old Belgrade and Zemun.

Source: Map drawn by Alison Manson, School of Geography, University of Leeds.

Planning Perspectives

217

Raspopovi

[ cacut e]

. A Museum to the Revolution of the People of Yugoslavia was to have been built

there too, but work was abandoned in the 1970s with only the foundations completed.

Figure 3. New Belgrade, showing the Sava and Danube rivers, and old Belgrade and Zemun (map drawn by Alison Manson, School of Geography, University of Leeds).

Building lives in New Belgrade

New Belgrade was built on marshlands that flooded every spring and autumn, and the initial

work of preparing the terrain was very hard. Eight million cubic metres of sand from the Sava

and the Danube was laid over the terrain to bed it down.

30

The work was done without proper

equipment but with much genuine enthusiasm, especially on the part of the thousands of youth

brigade members from all over Yugoslavia who took part. Photographs show large teams of

men and women transporting soil in wooden wheelbarrows. Lacking specialist machinery,

most work was done by hand. Contemporary accounts are cast very much in the idiom of the

triumph of civilization and the human will over the forces of nature, represented by the treach-

erous marshy terrain (Figures 4 and 5).

31

Figure 4. The rush of enthusiasm to lay the soil for the foundations of New Belgrade. Photograph reproduced from

Novi Beograd, 1961

by courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of Belgrade. Figure 5. The city appearing out of the marshland. Photograph reproduced from

Novi Beograd, 1961

by courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of Belgrade.

New Belgrade was laid out in orthogonal matrix blocks, 300 metres square. In this it

adhered closely to the 1957 General Urban Plan.

32

The vast extent of the planned new part of

Belgrade led inevitably to a permanently unfinished appearance, an impression reinforced by

the fact that the construction of apartment blocks had started in that part of the district that lay

furthest from Belgrade, proceeded by work on blocks closer to the Sava and the old city. In the

middle, the three central blocks remained empty. With the Danube to the north, Zemun to the

west and the Sava and beyond it central Belgrade to the east, a large swath of land to the south

was earmarked for industrial purposes.

33

A power station, shipyards and machinery factories

eventually filled some of this area, but a steelworks located there early on was bankrupted in

the 1970s. Perhaps the single largest departure from earlier concepts of New Belgrade was

the construction in the 1970s and 1980s of massive apartment blocks on the far side of the

c

Figure 4. The rush of enthusiasm to lay the soil for the foundations of New Belgrade.

Source: Photograph reproduced from Novi Beograd, 1961 courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of

Belgrade.

218

P. Waley

industrial zone (in Blocks 61, 62 and 63). This was a clear move away from a more sensitive

and expensive modernism towards the technocratic monumentalism of socialist urbanism.

Neither were these buildings so different, however, from the

grands ensembles

built around

Paris, Lyon and other French cities.

The huge scale of New Belgrade made it a very expensive enterprise, and it was not possi-

ble to rely long on the enthusiasm of youth brigades. Contributing to the expense was the lavish

choice of materials, both inside and out, and the care given to the configuration of buildings in

the blocks. As with so many Yugoslav development plans, such expense was only made

possible through centralized funding predicated on loans from abroad and earnings from the

export of military hardware. But if the state controlled the whole process of construction, at a

local level there was a degree of experimentation with community organizations. In the various

plans of the 1950s, New Belgrade was laid out along lines similar to the Soviet

raion

and

mikro

raion

, community structures for new housing estates.

34

These were implemented as

stambene

zajednice

, or residents associations. These later developed into the

mesne zajednice

alongside

reforms of national systems of government which introduced throughout Yugoslavia the

concept of self-management (

samoupravljanje

). In line with Soviet planning prescriptions,

each block was to have a number of community facilities, including a post office, nursery,

Figure 5. The city appearing out of the marshland.

Source: Photograph reproduced from Novi Beograd, 1961 courtesy of the Town Planning Institute of

Belgrade.

Planning Perspectives

219

elementary school and supermarket as well as sufficient green space and playgrounds. These

were to be centrally placed, with residential buildings aligned around them.

New Belgrade had originally been planned, along Corbusian modernist lines, to become the

federal capital for the new Yugoslavia. It is ironic then, as Ljiljana Blagojevi

[ cacut e]

has pointed out,

that with the exception of a few isolated landmark buildings it became a giant residential

suburb.

35

It is ironic too that this residential suburb came to incorporate a fairly distinct hier-

archy. The best housing was to be found in the central blocks located on either side of New

Belgrades empty axis. These were allocated to employees of various federal ministries and

agencies and of the military, according to the Yugoslav system of socially owned property,

where state institutions and companies invested in housing for their employees (Figure 6).

36

Figure 6. One of the classic apartment blocks, in Block 22.

As I have already indicated, its sheer scale and the lack of means to continue construction

meant that New Belgrade was always a work in slow progress, progress exacerbated in its early

stages by the split with Moscow in 1948. As mentioned above, a sense of dissatisfaction with

the development of New Belgrade was expressed by Milo

[ s car on]

Perovi

[ cacut e]

in a study undertaken in

the late 1970s under the auspices of the Institute for Development Planning of the City of

Belgrade. The static planning procedure and the exaggeratedly extensive open areas and

over-large building structures, he wrote, [have] led to New Belgrade becoming a monotonous,

c

s c

Figure 6. One of the classic apartment blocks, in Block 22.

220

P. Waley

unattractive town.

37

These criticisms found an echo in one of the entries to an inconclusive

competition held in 1980 to find a winning design for the three blocks on the central axis

between the Federal Executive building and the railway station. The submission from architects

Serge Renaudie and Pierre Guilbaud and the renowned French urban theorist Henri Lefebvre

was accompanied by a long preamble in which they took the modernist urbanism of New

Belgrade to task for ignoring the distinctiveness of place and failing to address the complexity

of cities.

38

If New Belgrade can be seen as a space that was, in the end, hierarchically organized, it

also enshrined an important sense of being representative, representative of the whole of

Yugoslavia. The system of balances that existed meant that top federal military and civilian

officials needed to reflect the national composition of the whole country. The residents of

the more central blocks were as a consequence drawn from all over the country. New

Belgrade was considered to belong to the people of all Yugoslavia, while old Belgrade on

the other side of the Sava River was the home of Beogradjani, residents of the city of longer

standing.

Within the modernist uniformity of the older New Belgrade blocks, there was a consid-

erable amount of architectural variation. This resulted primarily from the choice of different

architects for the main blocks, with each one laying buildings out according to a different

formation within the same orthogonal layout. A certain pride is said to have developed for

specific blocks, and more generally for the blokovi (blocks) of New Belgrade, expressed in

imaginative names reflecting elements such as a distinctive layout.

39

Nevertheless, New

Belgrade shared some of the often-observed inconveniences and lacunae of modernist and

socialist planned communities. Despite the presence of small supermarkets in each block, there

was a shortage of commercial outlets selling anything other than daily needs. The Merkator

Shopping centre on Block 11c was considered dark and unappealing, with poor communica-

tion between its different levels. New Belgrade suffered too from a dearth of cultural and

entertainment amenities only one cinema and the Museum of Contemporary Art, tucked

away among trees near the confluence of the Sava and the Danube.

Perhaps the dominant impression that New Belgrade conveyed was one of open space

and incompleteness. The very centre of New Belgrade was an open axis between the Federal

Executive building and the railway station, but this was interrupted in the mid-1980s when

housing was built on Block 24, adjacent to the station. The station itself remained marginal

within the countrys transport network, little more than a suburban stop, and the blocks by

its entrance were undeveloped. Cultural facilities were planned but not built. Schools and

shops were insufficient. The sense of incompleteness was reinforced by a certain responsive-

ness to changing architectural ideas, both within Yugoslavia and beyond, and buildings,

arguably creating thereby an urban landscape that is anything but static. The construction

of housing in Block 19a was one example, in which traditional elements were combined

with modernist features such as flexible units and movable partitions.

40

Another was the

Sava Centre, across the road from Block 19a, which opened in 1979 and occupied a strategic

position between the main New Belgrade blocks and the Sava River. As if to emphasize the

unfinished nature of New Belgrade, what should have been one of the most prestigious

spaces, along the Sava, was occupied, as a result of tenancy rights contracted with one of the

big state-owned companies, by small, self-built rural-style houses, many of them inhabited

by Roma.

Planning Perspectives 221

The wider framework of change in Serbia

War and the deprivations that coloured the lost decade of the 1990s greatly exacerbated living

conditions in Belgrade and throughout Serbia. Sanctions only served to strengthen the grip on

power of Slobodan Milo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] and those around him, who had monopolistic control of many

strategic commodities. The opposition to Milo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] and his Socialist Party was always strong,

but he managed, ruthlessly, to control and suppress it. Serbia (at this time, part of residual

Yugoslavia) became a highly centralized country, with all the key levers of political and

economic power under the control of the Socialist Party and its lackeys. A country that had

become radically decentralized with the passage of the new constitution in 1974 now became

vastly reduced and suffocatingly centralized. Indeed, Vujo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] and Nedovi[ cacut e] -Budi[ cacut e] argue that

the re-centralization of government and weakening of the constitutional role and planning

authority of the local communes was the main characteristic of the 1990s.

41

Planning in

Belgrade became inevitably centralized.

In some ways the transition in Serbia has followed patterns set in other CEE countries. In

other ways Serbia has very much followed its own path (or, perhaps, a specifically Western

Balkan path), characterized by what is generally known as a blocked, prolonged or delayed

transition, caused by war and authoritarian government.

42

Both these divergent interpretations

can be seen reflected in housing policy and housing conditions in the 1990s. On the face of it,

housing privatization bore much in common with other transitional CEE countries. It was

conducted rapidly and ruthlessly, but this very rapidity and the political calculations that lay

behind it set Serbia apart. As Petrovi[ cacut e] points out, housing privatization was conducted so as to

solidify the grip on power of the ruling elite around Milo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] .

43

The same point is made by

Djordjevi[ cacut e] . As little as between 2% and 5% of housing, she points out, was left in public hands

by 1993. Those who benefited principally, alongside the political elite, were urban dwellers,

and in particular professional, managerial and other members of the middle class. Housing

privatization, Djordjevi[ cacut e] writes, acted as a shock absorber that gave impoverished middle-

class households the impression that they were not among the losers in the transformation.

44

Flats were released to tenants at a third of their market value on highly favourable loan terms.

But this extent of privatization was highly inappropriate for a country as poor as Serbia, in

which, once a period of raging inflation had been overcome, salaries were low when they were

paid at all and prices remained very high.

The 1990s saw a decline in legal housing construction. At the same time illegal construc-

tion of housing, which had been a significant feature of socialist Yugoslavia, continued apace,

as more and more people were pushed into the black market to meet their housing needs.

45

Vujo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] and Nedovi[ cacut e] -Budi[ cacut e] , in considering the challenges facing planners in the early

2000s, argue that Massive illegal construction as a long-lasting tendency is perhaps the most

complex and serious obstacle to introducing a more organized spatial pattern.

46

Vujovi[ cacut e] and

Petrovi[ cacut e] refer to estimates that 10% of housing stock in Belgrade is illegal, representing over

40,000 separate buildings.

47

It is perhaps not surprising that the legislative emphasis over the

last few years has been on legalizing illegal constructions, rather than on preventing their

construction.

Illegal construction was generally a problem of the old city. In the apartment blocks of New

Belgrade, maintenance was the problem in the 1990s for those who had recently purchased the

apartments in which they lived. The country for which New Belgrade had originally been

conceived as a capital was falling apart, and there was little available for the upkeep of the

s c

s c

s c c c

c

s c

c

c

s c c c

c

c

222 P. Waley

buildings themselves and their surrounding land. In a number of blocks, permission was

granted for the construction on the roofs of buildings of small apartments whose occupants

would be contracted to undertake maintenance tasks. The experiment appears to have been less

than successful. Lifts ceased to function, and rubbish chutes became blocked. The centralized

heating systems failed.

48

Established residential communities were disrupted and dispersed by

the war, as they were in some areas by the privatization process. Refugees from Croatia and

Bosnia moved into apartments, especially in the massive southwest blocks (Blocks 6163), and

there was a rise in drug-related crime in a number of areas (the two developments seen by

many as being linked). Then, at the end of the 1990s, the coup de grace was delivered by

NATO bombs. A number of landmark buildings were damaged in the bombing campaign of

1999, notably the CK building, which had been appropriated by Milo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] s Socialist Party.

The top storeys of that building were severely damaged, and were subsequently removed

entirely when the building was renovated. Meanwhile, perhaps the most infamous casualty of

the NATO bombing was the Chinese Embassy, damaged beyond repair by a bomb that had

apparently been intended for a different target.

The contemporary planning framework in Serbia and its capital

Milo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e] s regime, unpopular but stubbornly resistant in Serbia, was finally deposed in the

turbulent events of October 2000. From then on, Serbias trajectory followed a path more simi-

lar to that pursued by other Central and Eastern European countries, albeit with a number of

distinctive characteristics. For those who envision a fairly predictable transition away from

socialism towards western European welfare capitalism, Serbia certainly presents some diffi-

culties and ambiguities. Not least of these involves planning regulation and the ownership of

urban land, where Serbia has occupied an ambivalent place somewhere between state and

market, and in many ways similar to that of China. Planning itself remains dominated by a

technocratic approach, with a focus on the provision of physical infrastructure, or, as Vujo[ s car on] evi[ cacut e]

and Nedovi[ cacut e] -Budi[ cacut e] suggest, it is now project-led cum market-based.

49

A crucial piece of post-2000 legislation was the Planning and Construction Act of 2003,

which was designed to lead the way to the private ownership of urban land.

50

This legislative

act was, however, widely criticized for turning its back on participatory, integrated planning

and for its restricted interpretation of the role of planning. A similar law, enacted in September

2009, was also designed to hasten the transfer of urban land to private ownership but was crit-

icized on similar grounds.

51

Questions remain concerning the establishment of monetary value

for usage rights as well as the current value of urban land. And various anomalies and grey

areas remain, for example the definition of the public realm, leaving it unclear as to whether

developers should also be made to install infrastructure. The 2009 law covers several other

important issues; for example, it introduces various measures that facilitate the legalization of

illegal constructions Above all, it is designed to harmonize planning, construction and property

ownership with EU norms.

One of the main issues tackled by the legislation is the conjoined one of ownership and

restitution of urban land. Urban land in Serbia is owned by the state, but in the case of

Belgrade, including New Belgrade, the national government delegates responsibilities to the

Belgrade municipal government, for whom the Belgrade Land Development Public Agency

actually carries out management tasks. To complicate matters, in New Belgrade, large old

s c

s c

s c

c c

Planning Perspectives 223

parastatal companies occupy important blocks and have tended to act as if they were owners

of the land. In a system not at all dissimilar to that which exists in China, property users pay a

use fee in effect, a lease to the state.

52

This lease, which had reached quite a high level

in New Belgrade by 2008, covers the total potential floor space on new build and thus encour-

ages vertical construction; what is more, floor area ratios can be raised if a case is made to the

city assembly. Vujovi and Petrovi write of a flourishing illegal commercial real estate

market through transactions with rights of use, although this probably applies less in New

Belgrade than in other urban areas.

53

Compared with the rest of Belgrade, urban development is much easier in New Belgrade

because interested parties know that issues of restitution do not exist. New Belgrade has,

indeed, seen the lions share of development projects in the first decade of this century. Almost

all the empty plots in New Belgrade have been leased, and the rest have been earmarked for

development. However, New Belgrade like the rest of the city, presents various drawbacks for

property investors. These relate to the obstacles and bureaucratic hurdles that are placed in

front of developers; it has taken longer to obtain construction permits in Serbia than in most

other countries in the world, and there have been more of them to be obtained.

54

In this context,

it remains to be seen how effective the new legislative measures will be. The lack of transpar-

ency and excess of bureaucracy in this process is recognized by the government in Belgrade,

and the 2009 Law on Planning and Construction is designed in part to speed up this process,

although relevant changes will also have to be implemented at the municipal level.

While the ambiguities that have clouded the regulatory environment have put off many

investors, others appear to have been attracted by the possibility of making considerably greater

profits than would be possible in a more tightly regulated and transparent market. A steady rise

in property prices in the middle part of the first decade of this century saw the price of residential

property in New Belgrade reach 2000 per square metre. The purchase price of a lease on

newly built property lagged behind, so that even when the per-square-metre cost of construction

was thrown in, a clear profit was accrued for developers. It is interesting to note that many invest-

ments in the property market in New Belgrade over the last decade have come, as well as from

domestic and foreign-based Serbian interests, from the wider Southeast European region, under-

stood here as stretching from Austria to Greece, with the important addition of Israel. Slovenian

investors were the first in, as they were familiar with the system of state ownership of urban

land, and they reaped the initial benefits. The first new retail centre in New Belgrade, the prom-

inently located new Merkator, was a Slovenian investment. Greek interests are active in a

number of sites in New Belgrade, most notably in the central Block 26. Israeli companies have

been particularly prominent in Belgrade, as they have in other major cities of CEE, more willing,

it would appear, to adapt to local regulatory and market conditions.

55

Two Israeli investments

in New Belgrade stand out for their size and prominence. The first is called Airport City, and

consists of two rows of large glass office blocks containing nearly 200,000 square metres,

constructed at a cost of 200 million.

56

The second is the same Block 26 in which Greek inves-

tors are active. But while Greek and Israeli investors have taken to the opportunities that they

have seen in New Belgrade and beyond, Turkish investors and construction companies, respon-

sible for a significant number of construction projects in Moscow, while reportedly keen to work

in Serbia, have been put off by the regulatory environment and high prices.

57

The political climate through the first decade of this century was not uniformly favourable

for foreign investments, as the prevailing mood lurched between a defensive nationalism and

c c

224 P. Waley

a more outward-looking liberalism. Nevertheless, the wide open spaces that remained in New

Belgrade at the turn of the century were tempting targets. The unfinished nature of the terrain

appeared to be inviting investments. There were plenty of positive factors for the boosters to

draw upon. These included Belgrades central position in Southeast Europe and its location at

the crossroads of two European transport corridors (7 and 10). Belgrade was chosen as South-

east Europes City of the Future; it hosted the Student Games in 2009 and the Eurovision Song

Contest in 2008. Prices rose, and with them, so did the developers hype. The talk of the town

towards the end of the decade was all about Russians buying property in Montenegro, and the

nouveaux riches of Montenegro buying up property in New Belgrade. The economic downturn

of the last years of the decade only really impacted on property development in Belgrade in

2009, but there is no special reason to believe that construction work will not pick up again in

the following few years.

New Belgrade as new business centre

New Belgrade today is a highly unusual monument to changing approaches to urbanism both

urban construction and urban design. It is unusual because it speaks so eloquently of changing

approaches to city building. Many of New Belgrades city blocks retain their classic modernist

appearance, combining a sense of social and communal solidity on the outside with a sort of

large-scale intimacy on the inside. The variation in configuration between the blocks is still

apparent, and one still gets a sense of the thought, care and expense that went into their

construction. Cars are generally absent from the areas inside the blocks, which manage as a

result to retain their communal facilities, including playgrounds for children and basketball

courts and these appear to be well used. There is plentiful provision of green space, some of

it landscaped and some not. And there are the social and commercial facilities kindergartens

and primary schools alongside shops, post offices and the like.

58

The blocks come in a number of different configurations of buildings, but many of them

are marked in some way by later constructions. Because of the generous use of space in the

original design for New Belgrade, there has been plenty of room for new developments.

The area was punctuated by new interpolations in various attenuated modernist styles, includ-

ing the Sava Centre, built in 1978 for a conference of the Organisation of Security and Coop-

eration in Europe, and culminating in the Genex building, designed by Mihajlo Mitrovi[ cacut e] and

completed in 1980, a striking twinned skyscraper dominating the approach to the city from the

west.

59

More recent constructions have introduced post-modernist styles, some of them delib-

erately discordant but distinctive, others bland and unmemorable. The locus classicus of obtru-

sive post-modernism stands on one of the main streets of New Belgrade next to the former

Federal Executive Building. This is the so-called Little Red Riding Hood building, designed

by Mario Jobst and completed in 1999 (Figure 7). This is and the buildings behind it are said

to be the domain of sports players, singers and new age entrepreneurs. The buildings in this

block are one might say middle-rise gated communities. Elsewhere, post-modernist accre-

tions have been tacked onto modernist blocks with little or no attention to style. Thus one row

of two-storey commercial outlets and offices, known as New Belgrades Wall Street, lines one

of New Belgrades central thoroughfares, obscuring the modernist block behind it.

Figure 7. The so-called Little Red Riding Hood building, in Block 12.

New landmarks have appeared reflecting changing social values. In a central part of New

Belgrade, a prominent indeed bulky church, St. Dimitrije, looks across the street at the

c

Planning Perspectives 225

New Merkator supermarket. These twin monuments to the mores of the new New Belgrade

need to be placed alongside another pre-eminent symbol of new social values, the Arena. This

large multi-purpose hall, built over a period of years in the 1990s, occupies a significant posi-

tion within New Belgrade; it fills the middle one of the three blocks in the central axis between

the former Federal Executive Building and the railway station. The Arena has acted as a venue

for tennis competitions, the Eurovision song contest and music concerts and political rallies of

a nationalistic stamp. Now, these three landmarks of 1990s New Belgrade have been overtaken

and overwhelmed by the two iconic developments of the New Belgrade of the 2000s, Airport

City and the Delta City shopping complex. The latter, which draws shoppers away from the

citys central pedestrian street, includes outlets like Marks & Spencer. Meanwhile, some of

the older landmark buildings have been re-clad and re-branded. Such is the fate (epitomizing

the changes that have occurred throughout New Belgrade) that has befallen the Yugoslavia

Hotel, part of which became a casino under the control of the Serbian war criminal [ Zcar on] eljko

Ra[ zcar on] natovi[ cacut e] (Arkan) and has more recently been re-opened as a casino by an Austrian

company.

60

In similar fashion, the damaged CK building has been re-clad, and is now an office

block. Stretches of New Belgrades waterfront are to be transformed through the construction

of a marina and an aquatic centre, paradigmatic features of post-modern urbanism. Most

Z

z c

Figure 7. The so-called Little Red Riding Hood building, in Block 12.

226 P. Waley

important of all the changes that have or are about to occur in New Belgrade is the strengthen-

ing of transport links with the city centre. One is the upgrading of the railway station and rail

link to the east bank of the Sava, accompanied by the development of the block on which the

station is located, and the other is the construction of a new road bridge between New Belgrade

and the city centre, a sine qua non for the further development of New Belgrade given the

congestion that characterizes the current road links.

In the makeover of New Belgrade centre stage has been held, appropriately enough, by

developments, long foreshadowed and then actual, in one the central block that stands across

the road from the former Executive Building. The development of Block 26 and those on either

side has, as we have seen, been a subject of longstanding controversy. One by one, these blocks

were filled in, leaving only Block 26 standing empty. The story of this development is a

complicated one. The current rights owners are two large conglomerates that had formerly

been socially owned, Napred and Energoprojekt. They have gone ahead with the construction

of office buildings in part of the block, and have controversially sanctioned the construction of

a church that now sits there looking totally out of context. The principal development project

involves the construction, financed by Israeli investors, of four large skyscrapers. At the time

of this writing, the project is on hold. However, it is clear that a new central business district

will materialize as a result of a project whose main thrust is upwards and which consists of the

provision of high-quality office space with a smaller residential component. The process

behind this pivotal development exemplifies the neo-liberal urbanism that has characterized

urban change in CEE over the last decade and longer. There has been a lack of public discus-

sion of development possibilities, and more precisely a lack of consultation among planning

experts.

61

At the same time, there has been an automatic presumption among the relevant

parties government, architectural elite and investors that a new business centre is required

and that this is best translated through the construction of high-rise buildings. The govern-

ments vision of New Belgrade as business centre was sketched out in the Belgrade 2021

Master Plan.

62

As such, there is minimal consideration given to the nature of the surrounding

urban landscape and still less of New Belgrade as an important monument to modern urbanism.

The patterns and tenor of life in New Belgrade today

New Belgrade is seen today by some observers as being characterized by ever greater

differentiation. Others have darker premonitions. Blagojevi[ cacut e] , for example, sees New Belgrade

as a city at war with itself, with a catastrophic deterioration of public space, unplanned

development, particularly of grey economy commercial outlets, and growing socio-spatial

fragmentation.

63

In trying to pick ones way through these various interpretations, one should

be mindful of the variety of housing types (existing already by the end of 1980s) which have

led, inevitably perhaps, to differentiated neighbourhoods.

64

The almost total privatization of

housing in New Belgrade (as elsewhere in the city) has contributed to the differentiation

between blocks. But at the same time, it has reinforced a district-wide socio-spatial patterning.

Flats in central blocks have risen in price, some of them quite steeply, while in other, more

peripheral blocks, a much more uneven pattern of occupation has arisen, with many flats rented

out on the private market. This contrast is borne out by research conducted by Mina Petrovi[ cacut e] .

In commenting on different perceptions of New Belgrade neighbourhoods, she concludes from

her survey that perceptions of safety were the predominant variant between residents of one of

c

c

Planning Perspectives 227

New Belgrades central blocks and one of its more peripheral blocks, and that these were

conditioned in large part by the spatial characteristics of the areas.

65

It is certainly the case that

the spatial characteristics of New Belgrade blocks today vary enormously. The very earliest

blocks, dating from the 1960s, have begun to look rather shabby, while the architectural and

design pedigree of the central blocks of the 1970s remains strikingly visible (Figure 6). From

then on, we have on the one hand the mega blocks of the districts south-western reaches

(Blocks 61 to 63) followed in short order by a much more varied constellation of housing

styles, including some very well designed low-rise housing near the Sava River and a wide-

spread and ever-growing infill of more recent housing, culminating in the huge Belvil devel-

opment, constructed for the 2009 Student Games, and then sold off to the private sector.

66

Amidst this rather unlikely diversity unlikely, that is, for an urban district whose concep-

tion and rationale is so unashamedly modern three types of residential environment can be

identified: prestige, modernist and peripheral. Apartments have become extremely expensive

(compared to average income levels) throughout the central blocks of New Belgrade, but the

buildings that have a special cachet as the residences of the rich are those of recent construction

such as the Little Red Riding Hood building mentioned earlier and others in the same block.

However, apartments are expensive throughout much of the central blocks of New Belgrade.

Block 30, in the centre of the district, next to Block 26 and the Little Red Riding Hood building

is a case in point. An apartment there in the early 1990s, at the time of privatization, cost

somewhere in the region of 4500 DM (about 1500 at the time a time of rapid inflation in

Belgrade). In 2008, apartments in the same block were selling for 150,000 to 200,000, with

a minimum price of 70,000 for one of the smallest apartments. The average was 2000 per

square metre, while across the road in the block containing the Little Red Riding Hood build-

ing, the average cost of a square metre was 3500.

67

The second type is the modernist apartment building, a feature of the central blocks of New

Belgrade. These central blocks retain to a large extent many of their outstanding original

features, designed by some of Yugoslavias best architects. The finest examples, in blocks 21,

22 and 23, have generous windows with wooden shutters and recessed balconies. They have,

in the words of Mihajlo Mitrovi[ cacut e] , designer of the Genex building, richly profiled facades.

68

In addition, these blocks still have central spaces that contain various communal amenities

shops, post offices, playgrounds, football and basketball courts, and the like. And for the most

part, these spaces are reasonably well maintained; certainly there is no evidence here of the

bleakness and anomie that one associates with socialist new towns in CEE.

69

Some of the

social fabric of the modernist design remains. Neighbourhood associations (mesne zajednice)

still exist, although no longer as social meeting places but as administrative, locally based

offices of the New Belgrade government, the op[ s c ar on] tina; they exist, but often do not function, and

there are now fewer of them in New Belgrade eighteen in all meaning that one association

covers several blocks and a large number of residents. Each building has its own residents

organizations (ku[ cacut e] ni savet), but unlike the president of the neighbourhood associations who

receives a salary from the local government, officials are unpaid, and residents organizations

are frequently all but dormant.

70

Given the size of the buildings and the fact that there are many

elderly residents who have been there since the days of Yugoslavia, difficulties arise in

organizing and financing maintenance.

The third type is that of peripheral residential areas, particularly in the south-western

extension of New Belgrade (Figures 8 and 9). Blocks 61, 62 and 63, with their huge prefabri-

c

s

c

228 P. Waley

cated concrete slabs and the more amenable buildings in blocks closer to the river Sava, were

completed after the central and north-western blocks, and built for a different type of resi-

dent, not for members of Yugoslavias ruling cadres but for ordinary low-income working

people, many of whom had jobs in the old city on the other side of the river. With the disin-

tegration of Yugoslavia and the economic and political disruption that ensued, a breakdown

of social norms occurred both in the wider territory of Yugoslavia but also in Belgrade, the

capital of rump Yugoslavia. In New Belgrade this manifested itself predominantly in the

harsher environments of the monolithic blocks and surrounding spaces of the south-west part

of the district (Figures 8 and 9). Drug taking became widespread, as portrayed in the 1998

film The Wounds (Rane), which depicts the lives of two would-be hoodlums and is largely

filmed in New Belgrade. Poverty and dislocation was generally seen to create a sense of

fragmentation. It was against this background of an already degraded environment that an

influx of Chinese occurred, the beneficiaries of an open visa regime negotiated by the

Chinese and Yugoslav governments. One particular area within New Belgrade, in Block 70,

became the basing point and distribution centre for Chinese commercial undertakings

throughout the Balkans.

71

The presence of a relatively large number of Chinese at a time of

great economic hardship produced reactions that ranged between bewilderment and hostility.

Figure 8. A view of pre-fab panel housing in Block 70a in New Belgrade.

Planning Perspectives 229

The Chinese, however, remained, and today there are many signs that their presence is

accepted and in some quarters welcomed. A much older community in New Belgrade is that

of the Roma. The largest Roma settlement lay under the Gazela Bridge that crosses the Sava

River. Roma living there were making money through recycling, but were moved out and

dispersed in the summer of 2009 to make way for the reconstruction of the bridge.

72

This

was just the latest of numerous attempts to remove the settlement and re-house its

inhabitants.

Figure 8. The panorama of Pre-fab panel housing in Block 70a in New Belgrade. Figure 9. The close-up of the later phases of the development of Pre-fab panel housing in Block 70a in New Belgrade.

Despite the potential for social fragmentation, New Belgrade remains a district of choice

for a significant number of people.

73

Undoubtedly one of the main reasons is the proximity of

the two rivers, the Sava and the Danube. The Sava in particular is lined with bars and cafs

which are particularly popular with people from both banks of the river. The ability to sit on a

barge on the river sipping a drink is an amenity the like of which is not to be found in many

other large European cities. In addition, the residents of New Belgrade have about 25 square

metres of green space each as opposed to an estimated seven to eight square metres in the old

city.

74

There are of course issues and problems. The large expanse of parkland near the

confluence of the Sava and the Danube, part of which was formally designated Friendship Park

(Park Prijateljstva), is sorely in need of maintenance. The same can be said of many of the

Figure 9. Pre-fab panel housing in Block 70a in New Belgrade.

230 P. Waley

green spaces within blocks, part of the more generalized failure to carry through affordable

plans for maintenance. The lack of car parking space is already a significant problem and likely

to become worse. The lack of bridges a situation only being remedied now leads to traffic

blockages and overcrowded buses crawling back and forth across the Sava to old Belgrade. In

the end, however, as Hirt argues, there are plentiful signs that New Belgrade remains an

attractive choice of place to live for many of the inhabitants of Belgrade, not least of which is

the high price of property there.

75

Figure 10. Parking is likely to become an ever greater problem. The inside of Block 22.

Concluding thoughts on preserving New Belgrade

New Belgrade might have been built according to classic modernist prescriptions, but it is testi-

mony to the rapid change in ideas, styles and the technology of residential architecture. The

purity of the classic modernist blocks has been compromised both at a district-wide level and

within and around the blocks by later constructions. There are prominently located parts of

New Belgrade where the modernist apartment blocks give way suddenly to housing from the

1980s, 1990s and 2000s, with coloured wall panels, curved corners and sloping roofs, so differ-

ent in spirit and style from the natural concrete, wooden frames, and strong lines of the

Figure 10. Parking is likely to become an ever greater problem. The inside of Block 22.

Planning Perspectives 231

modernist buildings. Away from the centre of New Belgrade, the purer spirit of the plans of

the 1960s and the buildings of the 1970s have been replaced by an approach that is in certain

areas more functional and in others more eclectic, with little attempt to provide community

structures and no investment in high-quality materials and design; here the open spaces along-

side the main thoroughfares have been eaten into by kiosks, small businesses and larger

commercial outlets. While in the former industrial belt that divided the old centre of New

Belgrade from the massive apartment blocks built to the south, large commercial and housing

projects are being completed now, on the plots left vacant by departing industries. Not only,

then, does New Belgrade end up by telling a revealing story of the history of housing styles in

the last 50 years, but it also reflects changes in urban planning and development. And equally

importantly, this vast monument to social housing has now become completely privatized

owner occupancy everywhere you look.

New Belgrade speaks to a wider story of social and urban change in the contemporary

world. It was created to reflect an internationalization predicated on the idea of a flat world

(one of international solidarity among non-aligned states and their peoples), but it has now

become subject to a literal Balkanization, a bumpy regionalism that sees Belgrade repositioned

as regional centre for Southeast Europe, with New Belgrade as its epicentre. Like the state

before it, capital has created its own spaces in New Belgrade, as it has its own geographies of

the region. It has also fashioned its own cultural logic, cultural practices and consumption

habits, alongside new disciplines of work and play, and these are colonizing the spaces of New

Belgrade. Nevertheless the vestiges of past eras (only recently past) continue to be a presence

in the landscape and an influence on peoples imaginations. It is hoped that this paper might

have two outcomes. The first is further research, building on that already undertaken by

Petrovi[ cacut e] and colleagues, on the changing relationship between the residents of New Belgrade

and their environment.

76

The second is a strengthening of moves to have the modernist blocks

and layout of New Belgrade preserved and internationally recognized.

Despite being such a large-scale and thorough example of socialist modernism, there have

been no attempts to date to preserve any part of New Belgrade, although there is support for

the idea in some quarters. This lack of interest stems no doubt from three factors: the failings

of modernist urbanism, the shortcomings of socialist urbanism and the failure and collapse of

Yugoslavia. Modernist urbanism calls for a sense of completeness. It leaves no space for

blemishes or exceptions. But the sheer size of New Belgrade meant that it was never complete.

Construction work in parts of the district had already departed from the prescriptions of

modernism by the 1980s. The shortcomings of socialism were manifested both in failures of

management and of equity. The scale of the project put it beyond the resources of Yugoslavias

federal socialist government, while on the ground the inability to secure a sufficient supply of

housing led to the construction of monumental apartment blocks that lacked the architectural

quality and communal facilities of the earlier blocks. Although the plan to locate federal

ministry buildings there was abandoned very early, New Belgrade was seen by its residents as

Yugoslav as opposed to Serbian old Belgrade. Residents of the older blocks worked in the

armed forces and federal ministries and so by definition came from all over the country. When

the country itself collapsed, so too did belief in the transformative power of New Belgrade. It

would be highly misleading however to suggest that the district is decaying or moribund. On

the contrary, the vigorous construction work that has filled empty spaces in the district and the

construction of new infrastructure including bridges suggest that New Belgrade is likely to

c

232 P. Waley

become one of the leading centres for business activity in Southeast Europe. One can only

regret that this is happening with little regard for the possibilities of preserving, if only in some

of the more central blocks, a sense of the modernist urbanism of which New Belgrade is such

an egregious example.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was undertaken primarily during visits to Belgrade in February

and July 2008 and interviews with planners, academics and architects. This paper was made possible as

a result of the generous help provided by a number of people. I am deeply indebted for help and guidance

to [ Zcar on] aklina Gligorijevi[ cacut e] , Miodrag Feren[ ccar on] ak, Zoran Eri[ cacut e] , Mina Petrovi[ cacut e] , Zoran Djukanovi[ cacut e] and Vanja

Ku[ ccar on] ina. Darko Radovi[ cacut e] , Ljiljana Blagojevi[ cacut e] and Jilly Traganou provided me with contacts and insights.

I would also like to thank Dejan Krajinovi[ cacut e] (Beobuild website), Slobodanka Prekajski (Belgrade Land

Development Public Agency), Nikola Mitrovi[ cacut e] (Dunavski Kej mesna zajednica) and Jovan Mitrovi[ cacut e]

(Medium International Development). I would also like to thank Marta Vukoti[ cacut e] Lazar for affording me

access to a number of useful volumes in the archives of the Institute of Urbanism Belgrade. Finally, I

would like to thank Vladimir Kuli[ cacut e] for reading through a draft and correcting a number of mistakes. Any

remaining errors and sins of omission and commission are of course entirely my own.

Notes on contributor

Paul Waley is a senior lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Leeds. His research grows out

of a strong focus on specific geographic settings both in East Asia and Southeastern Europe. Tokyo has

provided the context for much of his research, but recently he has undertaken research on the Balkans

and Italy, including work on Trieste, leading to a special themed issue of Social and Cultural Geography

(Vol. 10, No. 3) which he edited.

Notes

1. S. Hirt, Belgrade, Serbia, Cities 26 (2009): 300.

2. Lj. Blagojevi[ cacut e] , Strategies of Modernism in the Planning and Construction of New Belgrade, in

Stockholm Belgrade: Proceedings from the Third Swedish-Serbian Symposium in Stockholm, April

2125, 2004, ed. S. Gustavsson (Stockholm: Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and

Antiquities, 2007), 166.

3. Z. Nedovi[ cacut e] -Budi[ cacut e] and B. Cavri[ cacut e] , Waves of Planning: A Framework for Studying the Evolution of

Planning Systems and Empirical Insights from Serbia and Montenegro, Planning Perspectives 21

(2006): 410; S. Hirt, Landscapes of Post-modernity: Changes in the Built Fabric of Belgrade and

Sofia since the End of Socialism. Urban Geography 29 (2008): 801.

4. See, for example, Lj. Blagojevi[ cacut e] , Novi Beograd: Osporeni modernizam [New Belgrade: Contested

Modernism] (Belgrade: Zavod za Udzbenike, 2007); Z. Eri[ cacut e] , ed. Differentiated Neighbourhoods of

New Belgrade: Project for the Centre of Visual Culture at MOCAB (Belgrade: Publikum, 2009); I.

Mari[ cacut e] , A. Nikovi[ cacut e] , and B. Mani[ cacut e] , Transformation of the New Belgrade Urban Tissue: Filling the

Space Instead of Interpolation, Spatium 22 (2010): 4756. Lefebvres voice can be heard in

the entry that he submitted to a competition for the partial redesign of New Belgrade: S. Renaudie,

P. Guilbaud, and H. Lefebvre, International Competition for the New Belgrade Urban Structure

Improvement, Competition report (1986). Perovi[ cacut e] s views were expressed in: M. Perovi[ cacut e] , ed.

Iskustva pro[ s car on] losti: Lessons of the Past (Belgrade: Zavod za planiranje razvoja grada Beograda [Insti-

tute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade], 1985), a volume that was republished in

2008 (Belgrade: Gradjevinska Knjiga).

5. A. Dimitrijevi[ cacut e] , The Brave New Neighbourhoods of New Belgrade, in Differentiated Neighbour-

hoods, ed. Z. Eri[ cacut e] (Belgrade: Publikum, 2009), 117.

Z

c c c c c

c c c

c

c c

c

c

c

c c c

c

c

c c c

c c

s

c

c

Planning Perspectives 233

6. Mari[ cacut e] et al., Transformation of the New Belgrade Urban Tissue, 5. Amongst those who have made

New Belgrade a setting for some of their work is Belgrade-born writer and critic Mihajlo Panti[ cacut e] .

7. D. Smith, The Socialist City, 7099; I. Szelenyi, Cities under Socialism and After. Both in

Cities After Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and Conflict in Post-Socialist Societies, ed. G.

Andrusz, M. Harloe, and I. Szelenyi (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 286317; K. Stanilov, Taking

Stock of Post-socialist Urban Development: A Recapitulation, in The Post-Socialist City: Urban

Form and Space Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism, ed. K. Stanilov

(Dordrecht: Springer, 2007), 5.

8. C. Bernhardt, Planning Urbanization and Urban Growth in the Socialist Period: The Case of East

German New Towns, 19451989, Journal of Urban History 32 (2005): 10419.

9. Szelenyi, Cities Under Socialism.

10. K. Stanilov, The Restructuring of Non-residential Uses in the Post-socialist Metropolis, in The

Post-Socialist City, ed. K. Stanilov, 93.

11. B. Engel, Public Spaces in the Blue Cities in Russia, Progress in Planning 26 (2006): 155.

12. Stanilov, Housing Trends in Central and Eastern European Cities during and after the Period of

Transition, in The Post-Socialist City, ed. Stanilov, 181.

13. M. Czepczynski, Cultural Landscapes of Post-Socialist Cities: Representation of Powers and Needs

(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008): 81.